Abstract

Purpose

Wheat straw is an agricultural waste which can be used as a cost effective animal feed. However, high hemicellulose and phytic acid content in wheat straw prevents it as a primary feed choice. Utilization of wheat straw in solid-state fermentation may result in wheat straw valorization and enzyme production. In this study, phytase production in solid-state fermentation of wheat straw using Aspergillus ficuum and valorization of wheat straw were evaluated.

Methods

A two-step experimental design procedure was employed for screening and optimization of influencing factors on phytase production. Effects of different nutritional and environmental factors were investigated by one factor at the time method (OFATM). To reach higher amounts of phytase, response surface methodology (RSM) was employed to optimize phytase production as a function of three of the most effective factors.

Results

Optimization of the significant parameters resulted in an increase in the phytase activity from 0.74 ± 0.12 to a maximum of 16.46 ± 0.56 Units per gram dry substrate (U gds−1). The high degree of the fungal phytase activity on wheat straw resulted in the decrease in phytic acid content by 57.4%, as compared to the untreated sample. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and FTIR structural analysis showed intensive fungal growth on wheat straw, and partial removal of hemicelluloses, lignin and phytic acid.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated the feasibility of wheat straw utilization in solid-state fermentation using Aspergillus ficuum toward the production of phytase and valorization of wheat straw as an animal feed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wheat straw is the second most abundant lignocellulosic raw material in the world (Pensupa et al. 2013). The international grain council forecasted the annual world wheat production of 754 million tons in 2016 (ICG 2017) with a straw to grain ratio of 1.3 (for most wheat varieties). Surplus amount of straw has resulted in environmental and public health concerns attributing to the inefficiency of the conventional straw disposal or utilization methods. Currently, wheat straw is used as animal feed, as supporting materials (Panthapulakkal et al. 2006), as raw material for pulp and paper production (Nasser et al. 2015), and as a substrate for biogas, bioethanol, and mushroom production. Wheat straw is also burnt as a fuel and is added to soil for its maintenance (Ferreira et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2017; Mahboubi et al. 2017; Tomás-Pejó et al. 2017). Wheat straw contains 350–450 g kg−1 cellulose, making it an excellent potential source of energy for ruminants. However, intact straw is not an ideal feed for ruminants because of its high lignocellulose (200–300 g kg−1 hemicellulose and 80–150 g kg−1 lignin) and phytic acid content. Phytic acid, the main source of phosphorous in cereals, is not absorbed by monogastric animals, and due to its very strong chelating agent properties, it binds to metal ions (i.e., Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Fe2+) and proteins, making them unavailable for absorption. Furthermore, it inhibits the activity of a number of enzymes such as α-amylase, acid phosphatase and tyrosinase (Singh and Satyanarayana 2006a). Hence, phytic acid acts as an anti-nutritional factor in straw-derived feed components (Hurrell et al. 2003). On the other hand, phytic acid can find its way into waterways and consequently causes rapid algal growth and reduction in water oxygen content. This contributes to death of fish and hypoxia among other problems (Roopesh et al. 2006). These problems can be effectively addressed if the straw-derived feed diets are supplemented with phytase, an enzyme that degrades phytic acid. Phytase is produced naturally by several strains of bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi. Filamentous fungi have been widely used for the production of a wide range of extracellular enzymes and value-added supplements (Souza et al. 2015). Fungi-derived phytase has obtained considerable attention due to the ease of cultivation and high production yields (Roopesh et al. 2006). Various filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus sp. (Bhavsar et al. 2011; Moreira et al. 2014), Mucor racemosus (Bogar et al. 2003b), and Sporotrichum thermophile (Singh and Satyanarayana 2006b, Maurya et al. 2017), Thermomyces lanuginosus (Makolomakwa et al. 2017), and Rhizopus oryzae (Arora et al. 2017) have been reported to produce phytase. Several filamentous fungi and their enzyme products are used to break down the bond between the polysaccharides (cellulose and hemicellulose) and lignin in wheat straw to improve its digestibility through the process referred to as biological-pretreatment (Sindhu et al. 2016, Choudhary et al. 2016, Bagewadi et al. 2017). Many previous studies have also reported the ability of filamentous fungi to produce various commercial enzymes from wheat straw (Table 1).

However, only limited reports are available regarding the production of phytase from wheat straw using filamentous fungi (Singh 2014). The cultivation of filamentous fungi on wheat straw for phytase production could lead to the direct use of the crude product as a value-added supplement in feed mixtures (Bogar et al. 2003b). The aim of the present work is to evaluate phytase production through solid-state fermentation of wheat straw using filamentous fungi Aspergillus ficuum. Attempts were made to optimize the effective parameters on phytase production using response surface methodology. The effects of microbial growth on the physical and chemical characteristic of wheat straw were also investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Wheat straw was obtained from a local farm in Shiraz, Iran. It was dried in a forced air oven at 60 °C for 24 h, milled and sieved (0.21–0.84 mm). All the chemicals used in this research work were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany.

Microorganism

The fungus Aspergillus ficuum PTCC 5288 was maintained on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) slants at 30 °C for 4 days and stored at 4 °C. Inoculum was prepared by adding 10 mL of sterile distilled water with Tween 80 (1 mL L−1), to fully sporulated slant using a sterile pipette. The spores were gently agitated using a needle under strict aseptic conditions. The total spore count was determined by the Neubauer counting method.

Solid state fermentation of wheat straw

Solid-state fermentation of wheat straw (5 g dry weight) was carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Flasks were sterilized at 120 ± 1 °C and 15 psi for 20 min. After cooling, the substrate was moistened (under aseptic conditions) with a sterilized solution containing the additives (carbon source, nitrogen source, mineral salt) mentioned below, inoculated with the spore suspension of A. ficuum (106 spores gds−1) and incubated for 86 h (the time needed for the fully growth of the fungus on straw). The moisture level of 600 g kg−1, the substrate particle size of 0.70 ± 0.14 mm, and the temperature of 30 °C were used for all the tests, except otherwise specified. After fermentation, the fermented straw was mixed with 120 mL of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) at room temperature and agitated for 120 min at 180 rpm to extract the crude enzyme. Finally, the enzyme extract was centrifuged at 13000g and 4 °C for 15 min and the supernatant was collected for phytase activity determination. All the experiments described below have been performed in duplicate (except otherwise specified), and all the data points presented are the mean of duplicate runs.

Screening of the significant factors affecting phytase production

Fermentation experiments were carried out using one factor at the time (OFAT) experimental approach to screen among the effective factors on phytase production. Various carbon and nitrogen sources and mineral salts were examined to find out the required additives to the straw. The effects of variation in temperature, moisture, and substrate particle size on phytase production were also investigated.

Comparison of different carbon sources as inducers for the fungal growth and phytase production

An experiment was conducted to select the best carbon source to supplement wheat straw for rapid growth of the fungi. Mannitol, glucose, lactose, maltose, fructose, and sucrose were tested for this purpose. Each of the materials was added to the straw to the concentration of 0.1 g gds−1. The fermentation was conducted as described in Sec.2.3. A control run (without carbon source) was also included for this experiment.

Comparison of different nitrogen sources as supplements for the fungal growth and phytase production

Malt, ammonium sulfate, yeast extract, tryptone, sodium nitrate, ammonium nitrate, peptone and ammonium chloride were compared to find out the best nitrogen sources among them. Each of the materials was added to the wheat straw to the concentration of 0.05 g gds−1. Glucose (as the best carbon source) was added to the straw (0.1 g gds−1). The fermentation was conducted as described in “Solid state fermentation of wheat straw”. A control run (without nitrogen source) was also included for this experiment.

Comparison of different mineral salts as supplements for the fungal growth and phytase production

KCl, KH2PO4, K2HPO4, MgSO4, ZnCl2, MnSO4, NaCl, and FeSO4 were added to the straw to the concentration of 0.005 g gds−1. Glucose (0.1 g gds−1) and ammonium sulfate (0.05 g gds−1) were also added to the straw. The fermentation was conducted as described in “Solid state fermentation of wheat straw”. A control run (without any mineral salts) was also included for this experiment.

The effects of temperature, moisture, and particle size on the fungal growth and phytase production

Three sets of experiments were conducted to evaluate the effects of temperature (in the range of 25–35 °C), moisture (in the range of 400–750 g kg−1), and particle size (in the range of 0.25–0.70 mm) on the fungal growth and phytase production. The fermentation process was carried out as described in “Solid-state fermentation of wheat straw”. All the samples contained 0.1 g gds−1 glucose, 0.05 g gds−1 ammonium sulfate, and 0.005 g gds−1 manganese sulfate.

Response surface approach for optimizing phytase production

Response surface method (RSM) was applied to optimize phytase production as a function of moisture level, and glucose and ammonium sulfate concentrations, which were identified as the most effective factors on phytase production by the OFAT screening process. Each factor was studied at three different levels following the Box–Behnken design. The fermentation process was conducted as described in “Solid-state fermentation of wheat straw”. The experimental design for this part is depicted in Table 2.

A total of three replicates were carried out for each experimental set, and the average values are presented with standard deviation.

Analytical methods

Spectrophotometric (PG Instrument Ltd., UK) enzyme assay method was performed as described by Coban et al. (2015). One unit of phytase (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol/min of inorganic phosphorus from 1.5 mM sodium phytate under the assay conditions. The enzyme activity was expressed in units per gram of dry substrate (U gds−1), unless otherwise specified.

Structural analysis

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Tescanvega 3, Czech Republic) was used for the structural analysis of wheat straw. Fermented wheat straw was oven dried at 50 °C for 72 h. Dry fermented wheat straw was fixed on the aluminum stub and SEM image was captured. The investigation of the structural changes in the fermented wheat straw was also carried out using a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Impact 410 iS10, Nicolet Instrument Corp., Madison, WI, USA). The spectra of the fermented and untreated wheat straw were obtained with an average of 64 scans and resolution of 4 cm−1 from 600 to 4000 cm−1. The spectrum data were developed by Nicolet OMNIC 4.1 software (Nair et al. 2017).

Determination of phytic acid

A modified protocol of Harland and Oberleas (1977) was followed for the extraction of phytate from the untreated and fungal fermented wheat straw. The phytate content was measured based on the reaction between ferric ion and sulfosalicylic acid (Wade reagent) following the rapid colorimetric method described by Latta and Eskin (1980).

Results and discussion

Solid-state fermentation (SSF) of wheat straw using Aspergillus ficuum was carried out to produce phytase. Phytase production from wheat straw was found to improve its digestibility as observed with its structural analysis. To reach the maximum phytase production, efforts were made in this study to optimize the physical and nutritional parameters affecting the fungal phytase production, which is explained below.

Fungal phytase from wheat straw: screening for culture parameters

The effects of nutrient parameters such as carbon source inducers, nitrogen sources and mineral salts together with the physical parameters such as temperature, moisture content and wheat straw particle size, on phytase production were evaluated. Among the different carbon sources, glucose was found to yield the maximum phytase production (Table 3). Glucose has previously been reported as the most effective carbon source for phytase production from various microorganisms such as Myceliophthora thermophile (Hassouni et al. 2006), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Sasirekha et al. 2012), and Aspergillus flavus (Gaind and Singh 2015). The optimum nitrogen source was selected by supplementation of the media with 0.1 g gds−1 of glucose together with 0.05 g gds−1 of different nitrogen sources. Compared to other nitrogen sources, ammonium sulfate showed considerable improvement in the phytase production (Table 3). Similar observations were made by Bogar et al. (2003a), Singh and Satyanarayana (2006b), and Bala et al. (2014), demonstrating the significance of ammonium sulfate as the most favorable nitrogen source for phytase production. Among various mineral salts added to the cultivation media, MnSO4 exhibited maximum increase in phytase production.

Both the phosphate salts (KH2PO4 and K2HPO4) had an inhibitory effect on phytase production, which could be attributed to the phosphate existence in media and lack of need for phytate hydrolyzing and phytase production. Similar observations on the inhibitory effect of phosphate on phytase production have been reported previously. Exclusion of phosphate from the medium enhanced phytase production by A. niger (Żyła and Gogol 2002) and Sporotrichum thermophile (Singh and Satyanarayana 2006a).

Concerning the physical culture conditions, it was observed that the temperature variation in the range of 27–35 °C had no significant effect (p ≥ 0.05) on phytase production (Table 4).

Similarly, variation in wheat straw particle sizes in the range of 0.297 to 0.840 mm showed no significant effect on phytase production. However, reduction in particle sizes lower than 0.297 mm led to a decrease in the phytase production (Table 4). This drop might be due to compaction and consequent formation of agglomerates that contribute to a lower oxygen transfer (Schmidt and Furlong 2012). Table 4 shows that moisture variation significantly affects phytase production by the fungus. In the investigated range of 400–750 g kg−1, phytase production increased with the moisture content of the substrate and reached an optimum value at the moisture content of 650 g kg−1.

Response surface optimization of the effective process parameters

The significant factors influencing phytase production were optimized using response surface method. The predicted and observed responses are in Table 2.

The experimental data were fitted to a quadratic equation with phytase activity (U gds−1) as a function of the concentration of glucose (\(A\)), ammonium sulfate (\(B\)), and moisture content (\(C\)). The model is:

Table 5 shows the analysis of variance for the model. P value for the model was less than 0.0001, indicating that phytase activity is affected significantly by the model parameters. The test of lack of fit was insignificant (P value = 0.2467) indicating good fitness of the model with the experimental data. The values of coefficients of determination (R2 = 0.9909, Pred R2 = 0.9056, Adj R2 = 0.9791) indicated the suitability of the model to predict phytase activity as the function of the model parameters (Ghoshoon et al. 2015; Żyła and Gogol 2002).

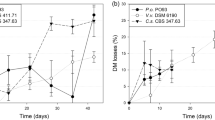

Using the model surface plots were generated showing interactions between factor pairs (Fig. 1). All the plots show a maximum value of phytase activity as the function of model parameters. The plots indicate that there is a unique optimum value of phytase activity as the function of moisture, and glucose and ammonium sulfate concentrations.

Response surface optimization predicted the maximum phytase activity of 14.51 U gds−1 in the medium containing 0.17 g gds−1 glucose, 0.068 g gds−1 ammonium sulfate and 655 g kg−1 moisture content. To verify the accuracy of the model for the prediction of the optimum value, an additional experiment was conducted with the mentioned values of moisture, and glucose and ammonium sulfate concentrations. The phytase activity of 14 U gds−1 was obtained which is reasonably close to the value predicted by the model (3.64% deviation).

To find if extension of the incubation time could improve the maximum phytase production, solid-state fermentation was performed for varying incubation time, with the culture parameters being constant at their optimum value.

The results (shown in Fig. 2) suggested that phytase production increased with the increase in incubation time, with the maximum enzyme production (16.4 U gds−1) at 144 h.

The enzyme activity, however, declined with further incubation, which could be attributed to the reduced nutrient level and enzyme deactivation. The straw-derived fungal phytase obtained in the present study was higher than phytase produced from other crop residues such as sesame oil cake (0.34 U gds−1) (Singh and Satyanarayana 2008), Groundnut oilcake (24.3 U gds−1) (Roopesh et al. 2006), soybean meal (16 U gds−1), wheat bran (4.5 U gds−1) (Chantasartrasamee et al. 2005) and cotton seed cake (1.10 U gds−1) (Singh 2014). Furthermore, Aspergillus ficuum strain (in the present study) showed higher phytase production in the solid-state fermentation of wheat straw, as compared to other filamentous fungal strains such as Aspergillus oryzae (Singh 2014).

To determine the effect of fungal fermentation on wheat straw, phytic acid was extracted from untreated and fermented wheat straw using hydrochloric acid. Analysis of the crude extract indicated a sharp decrease in phytic acid content from 23.5 ± 0.67 mg kg−1 in the untreated straw to 10 ± 0.83 mg kg−1 in fungal fermented straw, which indicates that the treatment reduces the phytic acid content of the straw effectively.

Structural analysis of fermented wheat straw

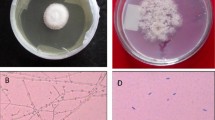

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was used to characterize the structural and surface morphology of the fermented wheat straw (Fig. 3).

The SEM image showed intense fungal growth on wheat straw and hyphae penetration in straw pores and channels (Fig. 3, bottom). The untreated wheat straw (control) image, however, showed the packed and inaccessible surface structures (Fig. 3, top). The fungal growth on wheat straw resulted in the destruction and modification of the fibrous structure and increase in the porosity. Fermented wheat straw also showed more accessible surfaces compared to the unfermented wheat straw (Fig. 3). The changes in the functional groups of wheat straw after fermentation were analyzed based on the FTIR spectra of the untreated and fermented wheat straw (Fig. 4). Peak assignments are summarized in Table 6, based on the previous literature reports (Kaushik et al. 2010; Shen et al. 2011).

The analysis of the FTIR spectra depicts significant changes in the structure of the fermented wheat straw compared to untreated wheat straw. Decrease in the polymerization of the cellulose chains was clearly indicated in the fermented wheat straw by the decrease in the absorbance of hydrogen bonds (O–H), represented at peak 3300 cm−1 (Oh et al. 2005) (Fig. 4). The absorbance intensity of the peak at 1730 cm−1 (that corresponds to the acetyl group) was reduced from 0.036 for untreated wheat straw to 0.032 for fermented wheat straw. Hemicelluloses bind to lignin via acetyl group. Therefore, this can be an indication of cleavage between hemicelluloses and lignin. A sharp peak at 1030 cm−1 corresponds to the phytate content (He et al. 2007; Ishiguro et al. 2003) and has significantly decreased in fermented wheat straw, indicating the partial removal of phytic acid (Fig. 4).

Conclusion

Solid-state fermentation of wheat straw using Aspergillus ficcum is a feasible way to valorize the straw as an animal feed. Addition of glucose as an inducer and ammonium sulfate enhance phytase production considerably. Maximum phytase activity of 16.4 U gds−1 was achieved at the optimum medium conditions using 0.17 g gds−1 glucose, 0.068 g gds−1 ammonium sulfate and 655 g kg−1 moisture after 144 h of incubation at 30 °C. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the fermented wheat straw showed high intensity of fungal growth resulting in the structural destruction and larger accessible surface area in the wheat straw. Chemical analysis and FTIR measurements of the wheat straw revealed the partial removal of phytic acid (57.4% reduction), hemicelluloses and lignin.

References

Arora S, Dubey M, Singh P, Rani R, Ghosh S (2017) Effect of mixing events on the production of a thermo- tolerant and acid-stable phytase in a novel solid-state fermentation bioreactor. Process Biochem 61:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2017.06.009

Bagewadi ZK, Mulla SI, Ninnekar HZ (2017) Optimization of laccase production and its application in delignification of biomass. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agric 6:351–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-017-0184-4

Bala A, Jain J, Kumari A, Singh B (2014) Production of an extracellular phytase from a thermophilic mould Humicola nigrescens in solid state fermentation and its application in dephytinization. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 3:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2014.07.002

Bhavsar K, Kumar VR, Khire J (2011) High level phytase production by Aspergillus niger NCIM 563 in solid state culture: response surface optimization, up-scaling, and its partial characterization. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 38:1407–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-010-0926-z

Bogar B, Szakacs G, Linden J, Pandey A, Tengerdy R (2003a) Optimization of phytase production by solid substrate fermentation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 30:183–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-003-0027-3

Bogar B, Szakacs G, Pandey A, Abdulhameed S, Linden JC, Tengerdy RP (2003b) Production of phytase by Mucorracemosus in solid-state fermentation. Biotechnol Prog 19:312–319. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp020126v

Chang AJ, Fan J, Wen X (2012) Screening of fungi capable of highly selective degradation of lignin in rice straw. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 72:26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.04.013

Chantasartrasamee K, Ayuthaya DIN, Intarareugsorn S, Dharmsthiti S (2005) Phytase activity from Aspergillus oryzae AK9 cultivated on solid state soybean meal medium. Process Biochem 40:2285–2289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2004.03.019

Choudhary M, Sharma PC, Jat HS, Nehra V, McDonald AJ, Garg N (2016) Crop residue degradation by fungi isolated from conservation agriculture fields under rice-wheat system of North-West India. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agric 5:349–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-016-0145-3

Coban HB, Demirci A, Turhan I (2015) Microparticle-enhanced Aspergillus ficuum phytase production and evaluation of fungal morphology in submerged fermentation. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 38:1075–1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-014-1349-4

Ferreira L, Nilsen P, Fdz-Polanco F, Pérez-Elvira S (2014) Biomethane potential of wheat straw: influence of particle size, water impregnation and thermal hydrolysis. Chem Eng J 242:254–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.08.041

Gaind S, Singh S (2015) Production, purification and characterization of neutral phytase from thermotolerant Aspergillus flavus ITCC 6720. Int Biodeter Biodegr 99:15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.12.013

Ghoshoon MB, Berenjian A, Hemmati S, Dabbagh F, Karimi Z, Negahdaripour M, Ghasemi Y (2015) Extracellular production of recombinant l-Asparaginase II in Escherichia coli: medium optimization using response surface methodology. Int J Pept Res Ther 21:487–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10989-015-9476-6

Harland B, Oberleas D (1977) A modified method for phytate analysis using an ion-exchange procedure: application to textured vegetable proteins [Soybeans]. Cereal Chem 54:827–832

Hassouni H, Ismaili-Alaoui M, Gaime-Perraud I, Augur C, Roussos S (2006) Effect of culture media and fermentation parameters on phytase production by the thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora thermophila in solid state fermentation. Micol Appl Int 18:29–36

He Z, Honeycutt CW, Xing B, McDowell RW, Pellechia PJ, Zhang T (2007) Solid-state Fourier transform infrared and 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectral features of phosphate compounds. Soil Sci 172:501–515. https://doi.org/10.1097/SS.0b013e318053dba0

Huang C et al (2017) An integrated process to produce bio-ethanol and xylooligo saccharides rich in xylobiose and xylotriose from high ash content waste wheat straw. Bioresour Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.109

Hurrell RF, Reddy MB, Juillerat M-A, Cook JD (2003) Degradation of phytic acid in cereal porridges improves iron absorption by human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 77:1213–1219. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1213

ICG International Grains Council (2017) Market Report 2017. http://www.igcint/downloads/gmrsummary/gmrsumme.pdf. Accessed June 2017

Ishiguro T, Ono T, Nakasato K, Tsukamoto C, Shimada S (2003) Rapid measurement of phytate in raw soymilk by mid-infrared spectroscopy. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:752–757. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.67.752

J-h Shen, Z-m Liu, Li J, Niu J (2011) Wettability changes of wheat straw treated with chemicals and enzymes. J Forest Res 22:107–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-011-0134-3

Kaushik A, Singh M, Verma G (2010) Green nanocomposites based on thermoplastic starch and steam exploded cellulose nanofibrils from wheat straw. Carbohydr Polym 82:337–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.04.063

Latta M, Eskin M (1980) A simple and rapid colorimetric method for phytate determination. J Agric Food Chem 28:1313–1315. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf60232a049

Mahboubi A, Ylitervo P, Doyen W, De Wever H, Molenberghs B, Taherzadeh MJ (2017) Continuous bioethanol fermentation from wheat straw hydrolysate with high suspended solid content using an immersed flat sheet membrane bioreactor. Bioresour Technol 241:296–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.125

Makolomakwa M, Puri AK, Kugen P, Singh S (2017) Thermo-acid-stable phytase-mediated enhancement of bioethanol production using Colocasia esculenta. Bioresour Technol 235:396–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.03.157

Maurya AK, Parashar D, Satyanarayana T (2017) Bioprocess for the production of recombinant HAP phytase of the thermophilic mold Sporotrichum thermophile and its structural and biochemical characteristics. Int J Biol Macromol 94:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.102

Mehboob N, Asad MJ, Asgher M, Gulfraz M, Mukhtar T, Mahmood RT (2014) Exploring thermophilic cellulolytic enzyme production potential of Aspergillus fumigatus by the solid-state fermentation of wheat straw. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 172:3646–3655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-014-0796-3

Moreira KA et al (2014) Optimization of phytase production by Aspergillus japonicus Saito URM 5633 using cassava bast as substrate in solid state fermentation. Afr J Microbiol Res 8:929–938. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2013.6565

Musatti A, Ficara E, Mapelli C, Sambusiti C, Rollini M (2017) Use of solid digestate for lignocellulolytic enzymes production through submerged fungal fermentation. J Environ Manage 199:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.05.022

Nair RB, Lundin M, Lennartsson PR, Taherzadeh MJ (2017) Optimizing dilute phosphoric acid pretreatment of wheat straw in the laboratory and in a demonstration plant for ethanol and edible fungal biomass production using Neurospora intermedia. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 92:1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.5119

Nasser RA, Hiziroglu S, Abdel-Aal MA, Al-Mefarrej HA, Shetta ND, Aref IM (2015) Measurement of some properties of pulp and paper made from date palm midribs and wheat straw by soda-AQ pulping process. Measurement 62:179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2014.10.051

Oh SY, Yoo DI, Shin Y, Seo G (2005) FTIR analysis of cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and carbon dioxide. Carbohydr Res 340:417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2004.11.027

Panthapulakkal S, Zereshkian A, Sain M (2006) Preparation and characterization of wheat straw fibers for reinforcing application in injection molded thermoplastic composites. Bioresour Technol 97:265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.043

Patel H, Divecha J, Shah A (2017) Microwave assisted alkali treated wheat straw as a substrate for co-production of (hemi) cellulolytic enzymes and development of balanced enzyme cocktail for its enhanced saccharification. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 71:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.12.032

Pensupa N, Jin M, Kokolski M, Archer DB, Du C (2013) A solid state fungal fermentation-based strategy for the hydrolysis of wheat straw. Bioresour Technol 149:261–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.09.061

Roopesh K, Ramachandran S, Nampoothiri KM, Szakacs G, Pandey A (2006) Comparison of phytase production on wheat bran and oilcakes in solid-state fermentation by Mucor racemosus. Bioresour Technol 97:506–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.046

Sasirekha B, Bedashree T, Champa K (2012) Optimization and partial purification of extracellular phytase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa p6. Eur J Exp Biol 2:95–104

Schmidt CG, Furlong EB (2012) Effect of particle size and ammonium sulfate concentration on rice bran fermentation with the fungus Rhizopus oryzae. Bioresour Technol 123:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.081

Sharma B, Agrawal R, Singhania RR, Satlewal A, Mathur A, Tuli D, Adsul M (2015) Untreated wheat straw: potential source for diverse cellulolytic enzyme secretion by Penicillium janthinellum EMS-UV-8 mutant. Bioresour Technol 196:518–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.012

Sindhu R, Binod P, Pandey A (2016) Biological pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass—an overview. Bioresour Technol 199:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.030

Singh B (2014) Phytase production by Aspergillus oryzae in solid-state fermentation and its applicability in dephytinization of wheat ban. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 173:1885–1895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-014-0974-3

Singh B, Satyanarayana T (2006a) A marked enhancement in phytase production by a thermophilic mould Sporotrichum thermophile using statistical designs in a cost-effective cane molasses medium. J Appl Microbiol 101:344–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02921.x

Singh B, Satyanarayana T (2006b) Phytase production by thermophilic mold Sporotrichum thermophile in solid-state fermentation and its application in dephytinization of sesame oil cake. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 133:239–250. https://doi.org/10.1385/ABAB:133:3:239

Singh B, Satyanarayana T (2008) Phytase production by a thermophilic mould Sporotrichum thermophile in solid state fermentation and its potential applications. Bioresour Technol 99:2824–2830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.010

Souza PMD et al (2015) A biotechnology perspective of fungal proteases. Braz J Microbiol 46:337–346. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-838246220140359

Thakur S, Shrivastava B, Ingale S, Kuhad RC, Gupte A (2013) Degradation and selective ligninolysis of wheat straw and banana stem for an efficient bioethanol production using fungal and chemical pretreatment. 3 Biotech 3:365–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-012-0102-4

Tomás-Pejó E et al (2017) Valorization of steam-exploded wheat straw through a biorefinery approach: bioethanol and bio-oil co-production. Fuel 199:403–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.03.006

Żyła K, Gogol D (2002) In vitro efficacies of phosphorolytic enzymes synthesized in mycelial cells of Aspergillus niger AbZ4 grown by a liquid surface fermentation. J Agric Food Chem 50:899–905. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf010551o

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Grant no.: 950508 of the Biotechnology Development Council of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Zohre Shahryari is grateful to the Pharmaceutical Sciences, Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Science for providing the facility for experiments and Vahid Niknezhad for his technical assistance and valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahryari, Z., Fazaelipoor, M.H., Setoodeh, P. et al. Utilization of wheat straw for fungal phytase production. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agricult 7, 345–355 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-018-0220-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-018-0220-z