Abstract

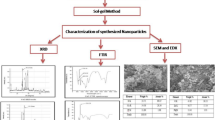

In this research, the effects of transition metal (Ni) doping to metal-oxide nanoparticles (TiO2) were studied. Various weight ratios (5, 10, 15, and 20%) of Ni-to-TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized using the sol–gel technique. These doped nanoparticles were prepared using titanium butoxide and nickel nitrate as precursors and methanol as a solvent. The effects of Ni doping to TiO2 were examined using a variety of characterization techniques, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform-infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy, field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The XRD reveals that the Ni-doped TiO2 crystallizes in a tetragonal structure with anatase phase. The particle size and lattice strain were calculated by Williamson–Hall equation. The presence of strong chemical bonding and functional groups at the interface of TiO2 nanoparticles was confirmed by FTIR. The optical properties of undoped and doped samples were recorded by UV–Vis spectroscopy. The saturation magnetization (Ms) was found higher for undoped as compared to doped samples. The surface morphology and the element structure of the Ni-doped TiO2 nanoparticles were examined by FESEM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing interest has been developed in nano-scaled semiconductors due to their vital roles in catalytic, optical, magnetic, and electrical applications. Size-dependent property of semiconductor nanoparticles is unique amongst many other remarkable properties. New exotic devices of unprecedented nature have been fabricated by these nanoparticles [1,2,3,4]. TiO2 is an extensively used semiconductor for photo-catalytic and solar cell applications due to its certain distinct features like band-gap modulation, environment-friendly nature, and straightforward synthesis routes via doping and grafting with visible light-absorbing dyes [5].

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) crystallizes in three different crystalline phase structures brookite, anatase, and rutile [6,7,8,9]. To investigate the electrical, optical, and magnetic properties of nanomaterials, profound efforts have been made [10]. Metals display distinctive physical and chemical properties owing to their limited size and high edge surface sites [11]. Doping has been studied widely both experimentally and theoretically. Dopants comprise nonmetals like S, N, C, etc. [12,13,14,15] and transition metals (TM) like Cu, Fe, Co, Ni, etc. [16,17,18]. It has been established by extensive researches that doping may apparently improve the photocatalysis, electrical, and optical properties of TiO2 [19,20,21]. Magnetic ion-doped TiO2 with room-temperature ferromagnetism, known as diluted magnetic semiconductors, has been extensively studied owing to its interest in potential applications in spintronics [22, 23]. Many efforts have been engaged in understanding the mechanism in this kind of DMS as the origin of ferromagnetism is not clear up to now. For example, the origin of ferromagnetism has been a very controversial topic for Ni-doped TiO2. Recently, Zhao et al. worked on Ni-impurity-induced reversible ferromagnetism in rutile TiO2 single crystals [24]. They argued that the magnetic source is Ni clusters. Recently, Bahadur et al. found that the magnetic moment of mixed crystalline TiO2 powders reduces with increasing Ni content. This is due to oxygen vacancies destroying a spin ordering [25].

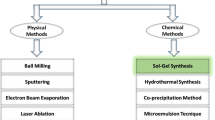

Moreover, Ni doping has also been studied for other purposes: controlling morphology [26], improving bandgap. Much attention has been paid to the preparation and characterization of titania in nanoparticle forms to increase the surface to volume ratio and thus to enhance photochemical reactivity. There exist various methods of producing titania nanoparticles, such as sol–gel process, electrochemical coating, hydrothermal process, hydrolysis, microemulsion method, thermolysis, flame aerosol process, chemical vapor deposition, etc. [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Sol–gel method is often employed as it offers the advantages such as precise control over the stoichiometry, low-temperature synthesis, high crystallinity, and high purity [36,37,38].

In this work, we report synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles doped with nickel in different weight ratios (5, 10, 15, and 20%) capable of having enhanced optical properties using sol–gel technique. The effects of the various dopant concentrations on the optical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles are studied. In addition, the structural, functional, and morphological analyses of the nanopowders were investigated.

Experimental details

Materials

Titanium(IV) butoxide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methanol and ethanol were obtained from Pancreac. Nickel nitrate hexahydrate was purchased from Uni-Chem.

Preparation of Ni-doped TiO2 films

Titanium-dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles were synthesized following a standard sol–gel technique using 13 ml titanium(IV) butoxide, 2.5 ml deionized water, 55 ml methanol, and 2 ml hydrochloric acid [39]. During the preparation, a mixture of water and ethanol was added slowly into a flask containing titanium butoxide, hydrochloric acid, and methanol. The solution was stirred for 2 h at 50 °C. The mixture was annealed at 450 °C for stable anatase-phase nanoparticles.

Preparation of Ni-doped TiO2 films

The precursor solution of the Ni-doped TiO2 (Ni:TiO2) films containing 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt% Ni ions was obtained by titanium butoxide and nickel nitrate hexahydrate with hydrochloric acid and methanol as the solvent and the chemical modifier, respectively. Ni content was defined as the weight% of Ni ions to the sum of those of Ti and Ni ions in the precursor solutions. The precursor solutions were spin-coated on a glass substrate 3500 rpm for 120 s.

Characterization

The particle size and phase information of TiO2 were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using PAN Analytical Xpert PRO XRD with Cu Kα radiation (0.154 nm) and 2θ values varying from 20° to 80°. UV–visible spectrophotometer (Genesys 10S) was used for absorption spectra measurements of films. The film morphology and microstructures were obtained using scanning electron microscope [field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), JSM-6460LV]. Fourier-transform-infrared (FTIR) spectrum of the samples was recorded using Perkin Elmer spectrometer. The magnetic properties (magnetization—M, retentivity—Mr, and coercivity—H) of the samples were measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer-vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) model Lakeshore-7407 at Bmax of 13 kOe.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 depicts XRD patterns of pure and various ratios of Ni-doped TiO2 nanoparticles calcined at 450 °C. The observed peaks confirm the formation of the anatase phase with the tetragonal structure of TiO2 matched with (JCPDS card no. 00-004-0477). It can be seen that pure TiO2 with small amount of doping (5 and 10%) exhibit diffraction peaks of anatase (101), (200), and (105) and brookite trace (211). Further addition of Ni generated peaks of rutile phase at (110) and (101).

X-ray diffraction was used to estimate peak broadening, associated with particle size and lattice strain due to crystal defect and dislocations [40]. The particle size of doped and pure TiO2 nanoparticle was determined using Williamson and Hall plot method. Peak broadening is contributed by induced strain and particle size effect. One contribution (particle size) depends on 1/cosθ and other (induced strain) varies as tangent θ. In the case of such broadening W–H plot is suitable for the extraction of particle size and lattice strain:

The peaks broadening in XRD pattern of doped TiO2 samples is due to doping concentration and the effect of small particle size. Induced strain and particle size of pure and doped samples were calculated from XRD pattern using W–H plot, as shown in Fig. 2a. The inverse intercept on Y-axis demonstrates particle size and slope of the line represents the lattice strain. In this study, particle size and lattice strain have decreased fashion with an addition of dopant material in TiO2 (Fig. 2b).

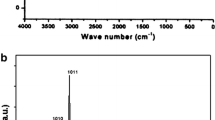

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of undoped and Ni-doped TiO2 nanoparticles calcined at 450 °C for 3 h. The spectra for all samples are identical and reflecting that doping has no effect on bonding environment present in the host material. The broadband around 4000–3200 cm−1 is attributed to symmetric and antisymmetric stretching vibrations of a single-bond functional group of –OH [41]. The peaks between around 2500 and 2300 cm−1 indicate the stretching of O=C=O bond [42]. Bending vibrations related to the hydroxyl functional group (H–O–H) appear between 1700 and 1300 cm−1. A large hump around 1100 cm−1 corresponds to Ti–O–Ti bonding [43]. The presence of all above functional groups is associated with the organic solvents utilized in this experiment during sol–gel synthesis of followed by washing with water and alcohols.

Figure 4 shows absorption spectra of pure and doped samples, and the maximum absorbance of undoped TiO2 was found around 285 nm, with a small amount (5%) of doping accompanied blue shift. The blue shift in the absorption spectra was explained by the Burstein–Moss effect at a particular dopant concentration. As the amount of charge carriers is increased, the Fermi-level lying in the conduction band is completely filled. Thereafter, the additional-excited electrons are supposed to enter the conduction band. However, beyond the 5% doping, the redshift was introduced in absorption spectra. This shift is associated with the doping as well as the formation of stable phase (rutile) of TiO2 as illustrated in XRD. The inherent reason for red shift in the band edge is due to the change of the sp–d exchange interactions between the band electrons and the localized d-electrons of the Ni+2 ions [44].

The calculated bandgap of TiO2 increases significantly from 3.40 eV to 3.88, 3.85, 3.59, and 3.78 eV upon 5, 10, 15, and 20% Ni doping, respectively (Table 1). This can be attributed to the introduction of new electron states in the band structure of TiO2 upon Ni doping [45]. With further increase in dopant concentration, the bandgap decreases. This trend is inconsistent with XRD results, where crystallite size decreases initially with doping and increases with increasing amount of Ni–TiO2. The band-gap values for undoped and doped samples are shown in Fig. 5a. The effect of doping on bandgap and particle size with various concentration of Ni in TiO2 is illustrated in Fig. 5b and Table 1.

The magnetic behaviors of undoped and Ni-doped TiO2 nanopowders are investigated with VSM, as shown in Fig. 6. The obtained curves revealed that the samples exhibited ferromagnetic behavior [46]. The graphs show typical hysteresis loops due to each specimen exhibiting coercivity and remanence (Fig. 6). It can be observed that undoped TiO2 has maximum Ms which depends upon induced lattice strain. The change in magnetic properties can be associated with the existence of lattice strain. This lattice strain related to small nanoparticles caused displacement of atoms which produced structure deformation as atoms present on the surface produce surface effect by variation in position of cations and anions that support development in magnetic behavior. The influence of strain on magnetic behavior in the current work also has correlation with strain-induced magnetic behavior reported previously by many authors [47,48,49,50]. Upon doping, Ms increased and this trend reverses with higher amount of doping well matched with the literatures [51, 52]. Hong et al. reported a decrease in Ms with increasing Ni doping, although the doping range was rather small compared to the present one [52]. From M–H curves, different parameters such as coercivity (Hc), remnant magnetization (Mr), and saturation magnetization (Ms) are calculated and are given in Table 2.

The doped-free image (Fig. 7a) has small and large grains composed of nanoparticles in the range of 10–20 nm which are in agreement with crystallite size measured from XRD by W–H plot method. As we added Ni–TiO2, small-scale agglomeration was observed (Fig. 7b) and this agglomeration increased significantly with increasing amount of Ni ions in the control sample, as shown in Fig. 7c–e. The observed particle size in doped TiO2 is around 50 nm with irregular and non-homogeneous distribution relative to doped-free TiO2.

Comparison between recent and reported studies regarding various concentration of Ni-doped TiO2 NPs with different fabrications techniques. The influence of dopant on particle size, bandgap, and magnetic saturation was studied, as shown in Table 3.

Conclusion

The undoped and various concentrations of Ni (5, 10, 15, and 20%)-doped TiO2 nanoparticles were successfully synthesized by sol–gel method at room temperature and then annealed at 450 °C. The XRD pattern revealed that the pure and doped fabricated samples have tetragonal system with anatase phase. The calculated particle size and lattice strain were decreased with increasing amount of Ni in TiO2 as confirmed by W–H plot and the presence of TiO2 was confirmed by Ti–O–Ti bounding in FTIR plot. The blue and red shift was found with small and higher contents of Ni–TiO2, respectively, which enhanced the bandgap with doping. The saturation magnetization depends on lattice strain; highest value of magnetization (Ms) can be attributed to large lattice strain and crystallite size relative to doped samples. Being a magnetic semiconductor Ni-doped TiO2 is a promising candidate for spintronics, oxygen sensor, electron transporting layer, and UV light absorber in photovoltaics.

References

Hoffmann, M.R., Martin, S.T., Choi, W., Bahnemann, D.W.: Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 95(1), 69–96 (1995)

Liao, D.L., Liao, B.Q.: Shape, size and photocatalytic activity control of TiO2 nanoparticles with surfactants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 187(2), 363–369 (2007)

Shankar, K., Bandara, J., Paulose, M., Wietasch, H., Varghese, O.K., Mor, G.K., LaTempa, T.J., Thelakkat, M., Grimes, C.A.: Highly efficient solar cells using TiO2 nanotube arrays sensitized with a donor-antenna dye. Nano Lett. 8(6), 1654–1659 (2008)

Kuang, D., Brillet, J., Chen, P., Takata, M., Uchida, S., Miura, H., Sumioka, K., Zakeeruddin, S.M., Grätzel, M.: Application of highly ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays in flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Nano 2(6), 1113–1116 (2008)

Munir, S., Dionysiou, D.D., Khan, S.B., Shah, S.M., Adhikari, B., Shah, A.: Development of photocatalysts for selective and efficient organic transformations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 148, 209–222 (2015)

Kiema, G.K., Colgan, M.J., Brett, M.J.: Dye sensitized solar cells incorporating obliquely deposited titanium oxide layers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 85(3), 321–331 (2005)

Keshmiri, M., Mohseni, M., Troczynski, T.: Development of novel TiO2 sol–gel-derived composite and its photocatalytic activities for trichloroethylene oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 53(4), 209–219 (2004)

Sharma, R.K., Bhatnagar, M.C., Sharma, G.L.: Mechanism in Nb doped titania oxygen gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 46(3), 194–201 (1998)

Tian, J., Gao, H., Deng, H., Sun, L., Kong, H., Yang, P., Chu, J.: Structural, magnetic and optical properties of Ni-doped TiO2 thin films deposited on silicon (100) substrates by sol–gel process. J. Alloys Compd. 581, 318–323 (2013)

Li, P., Nan, C., Wei, Z., Jun, L., Peng, Q., Li, Y.: Mn3O4 nanocrystals: facile synthesis, controlled assembly, and application. Chem. Mater. 22(14), 4232–4236 (2010)

Cammarata, R.C., Sieradzki, Karl: Effects of surface stress on the elastic moduli of thin films and superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62(17), 2005 (1989)

Francesca, S., Cappelletti, G., Ardizzone, S., Bianchi, C.L., Cappelli, S., Oliva, C., Scardi, P., Leoni, M., Fermo, P.: Solar photoactivity of nano-N-TiO2 from tertiary amine: role of defects and paramagnetic species. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 96(3), 314–322 (2010)

Harb, M., Sautet, P., Raybaud, P.: Anionic or cationic S-doping in bulk anatase TiO2: insights on optical absorption from first principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 117(17), 8892–8902 (2013)

Han, X., Shao, G.: Electronic properties of rutile TiO2 with nonmetal dopants from first principles. J. Phys. Chem. C 115(16), 8274–8282 (2011)

Wang, J.B., Wu, K.C., Mi, J.W., Luo, C.W., Wu, K.H., Uen, T.M., Lin, J.Y., Juang, J.Y., Liu, S.J.: Room-temperature ferromagnetism in carbon-and nitrogen-doped rutile TiO2. Appl. Phys. A 118(2), 725–731 (2015)

Di Paola, A., Garcıa-López, E., Ikeda, S., Marcı, G., Ohtani, B., Palmisano, L.: Photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds in aqueous systems by transition metal doped polycrystalline TiO2. Catal. Today 75(1), 87–93 (2002)

Wang, S., Meng, K.K., Zhao, L., Jiang, Q., Lian, J.S.: Superhydrophilic Cu-doped TiO2 thin film for solar-driven photocatalysis. Ceram. Int. 40(4), 5107–5110 (2014)

Samet, L., Nasseur, J.B., Chtourou, R., March, K., Stephan, O.: Heat treatment effect on the physical properties of cobalt doped TiO2 sol–gel materials. Mater. Charact. 85, 1–12 (2013)

Chen, X., Mao, S.S.: Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem. Rev. 107(7), 2891–2959 (2007)

Jones, F.H.: Teeth and bones: applications of surface science to dental materials and related biomaterials. Surf. Sci. Rep. 42(3), 75–205 (2001)

Diebold, U.: The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surf. Sci. Rep. 48(5), 53–229 (2003)

Prellier, W., Fouchet, A., Mercey, B.: Oxide-diluted magnetic semiconductors: a review of the experimental status. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15(37), R1583 (2003)

Shinde, S.R., Ogale, S.B., Higgins, J.S., Zheng, H., Millis, A.J., Kulkarni, V.N., Ramesh, R., Greene, R.L., Venkatesan, T.: Co-occurrence of superparamagnetism and anomalous Hall effect in highly reduced cobalt-doped rutile TiO2−δ films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92(16), 166601 (2004)

Zhao, Y.L., Motapothula, M., Yakovlev, N.L., Liu, Z.Q., Dhar, S., Rusydi, A., Breese, M.B.H., Wang, Q., Venkatesan, T.: Reversible ferromagnetism in rutile TiO2 single crystals induced by nickel impurities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101(14), 142105 (2012)

Bahadur, N., Pasricha, R., Chand, S., Kotnala, R.K.: Effect of Ni doping on the microstructure and high Curie temperature ferromagnetism in sol–gel derived titania powders. Mater. Chem. Phys. 133(1), 471–479 (2012)

Jing, D., Zhang, Y., Guo, L.: Study on the synthesis of Ni doped mesoporous TiO2 and its photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution in aqueous methanol solution. Chem. Phys. Lett. 415(1), 74–78 (2005)

Frindell, K.L., Tang, J., Harreld, J.H., Stucky, G.D.: Enhanced mesostructural order and changes to optical and electrochemical properties induced by the addition of cerium(III) to mesoporous titania thin films. Chem. Mater. 16(18), 3524–3532 (2004)

Musić, S., Gotić, M., Ivanda, M., Popović, S., Turković, A., Trojko, R., Sekulić, A., Furić, K.: Chemical and micro structural properties of TiO2 synthesized by sol–gel procedure. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 47(1), 33–40 (1997)

Tanaka, S., Hirose, N., Tanaki, T.: Effect of the temperature and concentration of NaOH on the formation of porous TiO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152(12), C789–C794 (2005)

Rodriguez, J., Gomez, M., Lu, J., Olsson, E., Granqvist, C.G.: Reactively sputter-deposited titanium oxide coatings with parallel penniform microstructure. Adv. Mater. 12(5), 341–343 (2000)

O’Neill, S.A., Clark, R.J.H., Parkin, I.P., Elliott, N., Mills, A.: Anatase thin films on glass from the chemical vapor deposition of titanium(IV) chloride and ethyl acetate. Chem. Mater. 15(1), 46–50 (2003)

Bersani, D., Antonioli, G., Lottici, P.P., Lopez, T.: Raman study of nanosized titania prepared by sol–gel route. J. Noncryst. Solids 232, 175–181 (1998)

Stark, Wendelin J., Baiker, Alfons, Pratsinis, Sotiris E.: Nanoparticle opportunities. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 19(5), 306–311 (2002)

Wilson, G.J., Matijasevich, A.S., Mitchell, D.R.G., Schulz, J.C., Will, G.D.: Modification of TiO2 for enhanced surface properties: finite Ostwald ripening by a microwave hydrothermal process. Langmuir 22(5), 2016–2027 (2006)

Goncalves, R.H., Schreiner, W.H., Leite, E.R.: Synthesis of TiO2 nanocrystals with a high affinity for amine organic compounds. Langmuir 26(14), 11657–11662 (2010)

Khanna, P.K., Singh, N., Charan, S.: Synthesis of nano-particles of anatase-TiO2 and preparation of its optically transparent film in PVA. Mater. Lett. 61(25), 4725–4730 (2007)

Wang, C.Y., Böttcher, C., Bahnemann, D.W., Dohrmann, J.K.: A comparative study of nanometer sized Fe(III)-doped TiO2 photocatalysts: synthesis, characterization and activity. J. Mater. Chem. 13(9), 2322–2329 (2003)

Farley, N.R.S., Staddon, C.R., Zhao, L., Edmonds, K.W., Gallagher, B.L., Gregory, D.H.: Sol–gel formation of ordered nanostructured doped ZnO films. J. Mater. Chem. 14(7), 1087–1092 (2004)

Mathews, N.R., Morales, E.R., Cortés-Jacome, M.A., Antonio, J.A.T.: TiO2 thin films—influence of annealing temperature on structural, optical and photocatalytic properties. Sol. Energy 83(9), 1499–1508 (2009)

Yogamalar, R., Srinivasan, R., Vinu, A., Ariga, K., Bose, A.C.: X-ray peak broadening analysis in ZnO nanoparticles. Solid State Commun. 149, 1919 (2009)

Ganesh, I., Gupta. A.K., Kumar, P.P., Sekhar, P.S.C., Radha, K., Padmanabham, G., Sundararajan, G. Preparation and characterization of Ni-doped TiO2 materials for photocurrent and photocatalytic applications. Sci. World J. 2012, 127326 (2012)

Nakhate, G.G., Nikam, V.S., Kanade, K.G., Arbuj, S., Kale, B.B., Baeg, J.O.: Hydrothermally derived nanosized Ni-doped TiO2: a visible light driven photocatalyst for methylene blue degradation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 124(2), 976–981 (2010)

Karthik, K., Pandian, S.K., Jaya, N.V.: Effect of nickel doping on structural, optical and electrical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles by sol–gel method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 256(22), 6829–6833 (2010)

Munir, S., Shah, S.M., Hussain, H.: Effect of carrier concentration on the optical band gap of TiO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Des. 92, 64–72 (2016)

Hu, J., Zhan, L., Zhang, G., Zhang, Q., Du, L., Tung, C.H., Wang, Y.: Effects of substitutional dopants on the photoresponse of a polyoxotitanate cluster. Inorg. Chem. 55, 8493–8501 (2016)

Parveen, B., Khalid, Z., Riaz, S., Naseem, S.: Room-temperature ferromagnetism in Ni-doped TiO2 diluted magnetic semiconductor thin films. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 15(2), 132–139 (2017)

Kotnala, R.K., Arya, G.S., Yogiraj, J., et al.: Strain-induced structural, magnetic and ferroelectric properties of heterostructure BST–NZFO nanocomposite thin film at room temperature. Bull. Mater. Sci. 40, 623 (2017)

Arya, G.S., Sharma, R.K., Negi, N.S.: Enhanced magnetic properties of Sm and Mn co-doped BiFeO3 nanoparticles at room temperature. Mater. Lett. 93, 341–344 (2013)

Smoleński, T., Kazimierczuk, T., Kobak, J., Goryca, M., Golnik, A., Kossacki, P., Pacuski, W.: Magnetic ground state of an individual Fe2+ ion in strained semiconductor nanostructure. Nat. Commun. 7, 10484 (2016)

Zhou, W., Liu, L., Wu, P.: Effect of biaxial strain on the magnetism of Fe16N2: density-functional investigations. Phys. Lett. A 378, 909–914 (2014)

Park, Y.R., Choi, S.L., Lee, J.H., Kim, K.J., Kim, C.S.: Ferromagnetic properties of Ni-doped rutile TiO2−δ. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 50(2014), 638–642 (2007)

Hong, N.H., Sakai, J., Prellier, W.: Distribution of dopant in Fe: TiO2 and Ni: TiO2 thin films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 281(2), 347–352 (2004)

Karthik, K., Pandian, S.K., Jaya, N.V.: Effect of nickel doping on structural, optical and electrical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles by sol–gel method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 256, 22 (2010)

Hermawan, P., Pranowo, H.D., Kartini, I.: Physical characterization of Ni(II) doped TiO2 nanocrystal by sol–gel process. Indones. J. Chem. 11, 135–139 (2011)

Tian, J., Deng, H., Sun, L., Kong, H., Yang, P., Chu, J.: Influence of Ni doping on phase transformation and optical properties of TiO2 films deposited on quartz substrates by sol–gel process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 4893–4897 (2012)

Rajamannan, B., Mugundan, S., Viruthagiri, G., Shanmugam, N., Gobi, R., Praveen, P.: Preparation, structural and morphological studies of Ni doped titania nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 128, 218–224 (2014)

Yan, Y., Uddin, M.J., Dickens, T.J., Daramola, D.E., Okoli, O.I.: 3D wire-shaped dye-sensitized solar cells in solid state using carbon nanotube yarns with hybrid photovoltaic structure. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 1, 1400075 (2014)

Bhatia, V., Dhir, A.: Transition metal doped TiO2 mediated photocatalytic degradation of anti-inflammatory drug under solar irradiations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4(1), 1267–1273 (2016)

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan and Center of Excellence in Solid State Physics for VSM characterization, Punjab University Lahore Pakistan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to urisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Manzoor, M., Rafiq, A., Ikram, M. et al. Structural, optical, and magnetic study of Ni-doped TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel method. Int Nano Lett 8, 1–8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40089-018-0225-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40089-018-0225-7