Abstract

Purpose of Review

Physical activity interventions aimed at older adults are frequently lead by younger trained professionals, often who have not experienced age-related changes in health status. The goal of this paper was to describe peer-led community-based interventions to assess whether this model is feasible for improving overall health and physical functioning.

Recent Findings

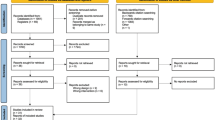

Twelve studies were included, with six different peer-led community-based programs: (1) Physical Training and Nutrition, (2) Project Healthy Bones, (3) Steady As You Go, (4) A Matter of Balance/Volunteer Lay Leader Program, (5) Healthy Eating, Active Lifestyles, and (6) Healthy Changes Program.

Summary

All programs showed positive effects on physical function, fall efficacy, quality of life, self-efficacy, and self-perceived health. Some reported decreased falls, frailty, and improved social activity. Peer-led programs appear promising to maintain and improve physical and social health. More research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of this approach for improving health and physical function, and reduce falls, and also assess long-term benefits and costs of this community-based intervention for older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Nelson M, Rejeski W, Blair S, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1094–105. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of physical activity, including lifestyle activities among adults—United States, 2000–2001. MMWR. 2003;52:764–9.

Warburton E, Nicol C, Bredin S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051351.

Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Progressive resistance exercise and resting blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2000;35:838–43. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.35.3.838.

Cuff DJ, Meneilly GS, Martin A, et al. Effective exercise modality to reduce insulin resistance in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):2977–82. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.11.2977.

Williams MA, Haskell WL, Ades PA, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2007;116:572–84. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185214.

Warburton D, Gledhill N, Quinney A. The effects of changes in musculoskeletal fitness on health. Can J Appl Physiol. 2001;26:161–216. doi:10.1139/h01-012.

Castenada C, Layne J, Munoz-Orians L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2335–41. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.12.2335.

Beniamini Y, Rubenstein J, Faigenbaum A, et al. M. High-intensity strength training of patients enrolled in an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 1999;19:8–17. doi:10.1097/00008483-199901000-00001.

Baker K, Nelson M, Felson D, et al. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1655–65.

Layne J, Nelson M. The effects of progressive resistance training on bone density: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:25–30. doi:10.1097/00005768-199901000-00006.

Nelson M, Fiatarone M, Morganti C, et al. Effects of high-intensity strength training on multiple risk factors for osteoporatic fractures: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;272:1909–14. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520240037038.

Braith R, Stewart K. Resistance exercise training: its role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2006;113:2642–50. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584060.

Todd C, Skelton D. What are the main risk factors for falls among older people and what are the most effective interventions to prevent these falls? Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network report; http://www.euro.who.int/document/E82552.pdf, Accessed 5 April 2004). 2004.

• Shier V, Trieu E, Ganz DA. Implementing exercise programs to prevent falls: systematic descriptive review. Inj Epidemiol. 2016;3:16. Epub 2016 Jul 4. This review identifies key characteristics of successful fall prevention exercise programs that can be used to determine which local options conform to clinical evidence.

Yan T, Wilber K, Aguirre R, et al. Do sedentary older adults benefit from communitybased exercise? Results from the Active Start Program. Gerontologist. 2009;49(6):847–855. doi:10.1093/%20geront/gnp113.

Layne J, Sampson S, Mallio C, et al. Successful dissemination of a community-based strength training program for older adults by peer and professional leaders: the People Exercising Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2323–2329. doi:10.1111/j.15325415.2008.02010.x.

Kim S, Koniak-Griffin D, Flaskerud J, et al. The impact of lay health advisors on cardiovascular health promotion. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(3):192–199. doi:10.1097/00005082200405000-00008.

O’Loughlin J, Renaud L, Richard L, et al. Correlates of the sustainability of communitybased heart health promotion interventions. Prev Med. 1998;27:702–712. doi:10.1006/%20pmed.1998.0348.

•• Wurzer B, Waters DL, Hale LA. Fall-related injuries in a cohort of community-dwelling older adults attending peer-led fall prevention exercise classes. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016;39(3):110–6. This study reports on the reported injuries and circumstances and to estimated costs related to falls experienced by older adults participating in Steady As You Go (SAYGO) peer-led fall prevention exercise classes.

Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:740–4.

•• Kapan A, Luger E, Haider S, et al. Fear of falling reduced by a lay led home-based program in frail community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2017;68:25–32. This study showed that a 12-week structured physical training and nutrition intervention carried out by lay volunteers also reduces fear of falling.

•• Nanduri AP, Fullman S, Morell L, et al. Pilot study for implementing an osteoporosis education and exercise program in an assisted living facility and senior community. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;11:1–18. This study showed that offering low-cost disease-specific programs helps minimize the complications of osteoporosis and improve the overall health of participants.

•• Luger E, Dorner TE, Haider S, et al. Effects of a home-based and volunteer-administered physical training, nutritional, and social support program on malnutrition and frailty in older persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMDA. 2016;671:e9-671–e16. This study showed that a home-based physical training, nutritional, and social support intervention conducted by non-professionals is feasible and can help to tackle malnutrition and frailty in older persons living at home.

•• Wurzer B, Waters DL, Hale LA, et al. Long-term participation in peer-led fall prevention classes predicts lower fall incidence. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2014;95(6):1060–6. This study showed that the SAYGO program appears to be an effective fall prevention intervention with a high attendance rate and a lower fall incidence with long-term participation.

•• Cho J, Smith ML, Ahn SN, et al. Effects of an evidence-based falls risk-reduction program on physical activity and falls efficacy among oldest-old adults. Front Public Health. 2014;2:182. This study reports on the effectiveness of evidence-based programs for increasing falls efficacy in oldest-old participants.

•• Smith ML, Ahn SN, Sharkey JR, et al. Successful falls prevention programming for older adults in Texas: rural-urban variations. J of Applied Gerontology. 2012;31(1):3–27. This study showed that rural participants, despite entering and exiting the program with lower health status, report greater rates of positive change for falls efficacy and health interference compared with their urban counterparts.

•• Batra A, Melchior M, Seff L, et al. Evaluation of a community-based falls prevention program in South Florida, 2008–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E13. This study showed that lay leaders could successfully implement the programs in community settings. The programs were also effective in reducing fear of falling among older adults.

•• Waters DL, Hale LA, Robertson L, et al. Evaluation of a peer-led falls prevention program for older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2011;92(10):1581–6. This study showed that a peer-led model maintained measures of strength and balance and was superior to seated exercise.

•• Ory MG, Smith ML, Wade A, et al. Implementing and disseminating an evidence-based program to prevent falls in older adults, Texas, 2007–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(6) This study showed that widespread dissemination of a peer-led program to prevent falls can promote active aging among people who would otherwise be at risk for a downward cycle of health and functionality.

•• Goldfinger JZ, Arniella G, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Project HEAL: peer education leads to weight loss in Harlem. J Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19(1):180–92. This study showed that a peer-led, community-based course can lead to weight loss and behavior change.

•• Healy TC, Haynes MS, Botler JL, et al. The feasibility and effectiveness of translating a matter of balance into a volunteer lay leader model. J of Applied Gerontol. 2008;27(1):34–51. This study showed that successful translation of a professionally led health promotion program into a volunteer lay leader model enables embedding the program in community-based organizations, thus making it more broadly available to older adults in diverse settings.

•• Klug C, Toobert DJ, Fogerty M. Healthy changes (TM) for living with diabetes: an evidence-based community diabetes self-management program. Diabetes Educator. 2008;34(6):1053–61. This study showed that the Healthy Changes program can be successfully translated into community settings and led by trained peer leaders, yielding health improvements similar to those reported in efficacy trials.

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner M. Randomized controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ. 1997;315:1065–9.

• Mielenz TJ, Durbin LL, Herzberg F, et al. Predictors of and health- and fall-related program outcomes resulting from complete and adequate doses of a fall risk reduction program. Transl Behav Med. 2016. This study showed that self-restriction of activities due to a fear of falling and physical activity levels may be simple and effective screening questions to prevent AMOB/VLL attrition.

• Washburn LT, Cornell CE, Phillips M, et al. Strength training in community settings: impact of lay leaders on program access and sustainability for rural older adults. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(7):1408–14. This study showed that program continuance was significantly and positively associated with lay leader use.

• Withall J, Thompson JL, Kenneth R, et al. Participant and public involvement in refining a peer-volunteering active aging intervention: Project ACE (Active, Connected, Engaged). Gerontologist. 2016; doi:10.1093/geront/gnw148. This study provides guidance for active aging community initiatives highlighting the importance of effective recruitment strategies and of tackling major barriers including lack of motivation, confidence, and readiness to change; transport issues; security concerns and cost; activity availability; and lack of social support.

Horne M, Skelton DA, Speeds S, et al. Attitudes and beliefs to the uptake and maintenance of physical activity among community-dwelling South Asians aged 60–70 years: a qualitative study. Pub Health. 2012;126(5):417–23.

Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14.

Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Jacquez A. Outcomes of border health Spanish/English chronic disease self-management programs. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:401–9.

Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Gonzalez VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management: a randomized community-based outcome trial. Nurs Res. 2003;52:361–9.

Robertson L, Hale B, Hale L, Waters DL. A qualitative study of community peer-led exercise groups, their wellbeing and social effects. Int J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2014;12(2).

Vecina Jiménez ML, Chacón Fuertes F, Sueiro Abad MJ. Differences and similarities among volunteers who drop out during the first year and volunteers who continue after eight years. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(1):343–52.

Chan WLS, Hui E, Chan C, et al. Evaluation of chronic disease self-management programme (CDSMP) for older adults in Hong Kong. J of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2011;15(3):209–14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Emalie Hurkmans, Birgit Wurzer, and Debra Waters declare no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wurzer, B.M., Hurkmans, E.J. & Waters, D.L. The Use of Peer-Led Community-Based Programs to Promote Healthy Aging. Curr Geri Rep 6, 202–211 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-017-0217-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-017-0217-x