Abstract

Overall cancer incidence has been observed to be lower in Mediterranean countries compared to that in Northern countries, such as the UK, and the USA. There is increasing evidence that adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern correlates with reduced risk of several cancer types and cancer mortality. In addition, specific aspects of the Mediterranean diet, such as high consumption of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, and low processed meat intake, are inversely associated with risk of tumor pathogenesis at different cancer sites. The purpose of this review is to summarize the available evidence regarding the association between the Mediterranean diet and cancer risk from clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and case–control studies. Furthermore, we focused on the different definitions of a Mediterranean diet in an attempt to assess their efficiency. Observational studies provide new evidence suggesting that high adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced risk of overall cancer mortality as well as a reduced risk of incidence of several cancer types (especially cancers of the colorectum, aerodigestive tract, breast, stomach, pancreas, prostate, liver, and head and neck).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2013, the number of deaths worldwide and throughout all age groups reached nearly 55 million, with 70 % of them caused by non-communicable diseases, including 15 % caused by cancer [1]. In spite of a decrease in death due to neoplastic disease since 1990, cancer remains a tremendous health problem. According to estimations by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the 5-year global cancer prevalence is ∼28.8 million in 2008. With respect to localization, the most prevalent cancer worldwide continues to be carcinoma of the breast. Prostate cancer is the most common neoplastic disease in the USA and Oceania as well as Western and Northern Europe [2].

For several decades now, observational studies point out that the incidence of overall cancer is lower in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea when compared to that in Northern countries, the UK, and the USA [3]. The concept of a “Mediterranean diet” (MD) was developed to reflect the typical dietary habits adopted during the early 1960s by inhabitants of the Mediterranean basin, mainly in Crete, much of the rest of Greece, and Southern Italy [4]. Adherence to a MD has previously been reported to be effective in the primary and secondary prevention of a number of chronic non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases [5•], neurodegenerative diseases [6], type 2 diabetes mellitus [7], and neoplastic diseases [8, 9].

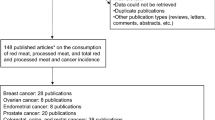

In 2014, we published a meta-analysis of observational studies investigating the effects of conformity with an MD on overall cancer risk (incidence and mortality) and risk of development of different types of cancer [10••]. Our findings further underlined the importance of a MD as a potential health-promoting dietary pattern, and it became reasonable to update this systematic review only a year later due to the large number of additional observational studies (14 cohort and 9 case–control studies) published in the interim brief period [11••]. In both meta-analyses, adherence to the highest category of MD was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of overall cancer mortality/incidence as well as the incidence of several cancer types (especially cancers of the colorectum, aerodigestive tract, breast, stomach, pancreas, prostate, liver, and head and neck).

The number of cancer survivors in the USA and Europe is rapidly growing [12, 13]. A few prospective cohort studies investigated the association between composition of the diet and cancer survival, reporting inconsistent results [14•]. For example, several studies focused on the evaluation of the relationship between survival and nutrients rather than dietary patterns [14•, 15]. The objective of the current review was to summarize the available evidence on Mediterranean diet and cancer risk (with respect to incidence, survival, and mortality) as well as to report on current results and futures directions. Prior to that, we provide an overview of the most common ways to define a Mediterranean diet.

What is a Mediterranean Diet?

The most commonly used operational definition of a MD is the Mediterranean Dietary score proposed by Trichopoulou et al. in 1995 [16], which was updated in 2003 [17]. The Mediterranean score is built by assigning a value of 0 or 1 to each of nine components with the use of sex-specific medians as the respective cutoffs. In detail, this MD score is characterized [17] by six beneficial components (high consumption of vegetables, fruits and nuts, legumes, unprocessed cereals, fish, and a high ratio of monounsaturated fatty acids to saturated fatty acids) and two components regarded to be detrimental (meat and meat products including poultry and dairy products with the exception of cheeses preservable for a long period of time). With respect to favorable ingredients, persons whose consumption is at or above the median receive a score of 1 for each category, and persons whose consumption is below the median receive a score of 0. With respect to unfavorable ingredients, the scoring system is applied with reversed signification. The potential benefit of moderate alcohol consumption is taken into account by assigning a value of 1 to men who consume between 10 and 50 g per day and to women who consume between 5 and 25 g per day, respectively [17]. The highest adherence to a MD is therefore represented by a maximum score of 9.

The second most widely used MD score is an alteration of the original score by Trichopoulou adapted by Fung et al. in 2006 [18]. The following components were either excluded or modified: exclusion of potato products from the vegetable group, separation of fruits and nuts into two groups, exclusion of the dairy group, inclusion of whole-grain products only, inclusion of red and processed meats only in the meat group, and assignment of 1 point for alcohol intake between 5 and 15 g/day. In 2014, Whalen et al. [19] modified this alternate MD score with respect to dairy foods, grains and starches, and alcohol intakes. Another variation of the score by Trichopoulou et al. [17] was introduced by Tognon et al. [20] and Xie et al. [21] by adding fruit juices and polyunsaturated fatty acids, focusing on whole grains, and excluding poultry. The MD score established by Panagiotakos et al. in 2007 [22, 23] is based on 11 main components (non-refined cereals, fruits, vegetables, potatoes, legumes, olive oil, fish, red meat, poultry, full-fat dairy products, and alcohol). Consumption of items adhering to this pattern will result in scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 when a participant reported no, rare, frequent, very frequent, weekly, and daily consumption, respectively. Three of the 11 components were considered to exert detrimental effects (red meat, poultry, full-fat dairy products). For alcohol, a value of 5 is assigned to subjects who consume <300 ml (12 g ethanol) alcoholic beverages per day, and a value of 0 is applied if alcohol consumption is either >700 or 0 ml/day.

Other infrequently used MD scores include the Mediterranean Diet quality index [24], the Mediterranean Score by Goulet et al. [25], the Mediterranean Diet pattern score [26], the Mediterranean dietary pattern adherence index [27], and the Mediterranean Adequacy Index [28].

Mediterranean Diet and Cancer Risk

Overall Cancer Mortality

RCTs

The first clinical trial to demonstrate the protective effects of the MD in the secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease was the Lyon Diet Heart study. Participants were asked to replace butter and cream with a special alpha-linolenic-acid-rich margarine. Apart from cardiovascular diseases, protective effects of an MD were also reported with respect to the risk of cancer development [29]. Results of the study were transferred into the following food advices: to increase the consumption of vegetables, fruits, and fish, but to reduce the consumption of red meats.

Besides the Lyon Diet Heart study, there is only one other randomized controlled trial of a Mediterranean diet reporting on cancer risk. The “Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea” (PREDIMED) trial focused on the intake of extra virgin olive oil (50 g/day) and nuts (30 g/day) in the intervention groups [30••]. Results including 7447 subjects showed that the highest category of nut intake (>3 servings/week) was associated with a 40 % risk reduction of cancer mortality when compared to the lowest category [31•], whereas the differences observed between consumption categories of extra virgin olive oil did not attain statistical significance [32•].

Prospective Cohort Studies

Overall risk of cancer mortality was evaluated in 11 cohort studies (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), Nurses’ Health Study, Health Professionals Follow-up Study, Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, Multiethnic Cohort, HALE and SENECA study, SUN-cohort, Seven Countries Study, National Institutes of Health American Association of Retired Persons (NIH-AARP), Västerbotten Intervention Program-cohort, Swiss National Research Program 1A, MONICA) [20, 33–42]. Six of these cohorts did not show a significant correlation between adherence to an MD and cancer risk. However, pooling all 11 cohort studies in a meta-analysis yielded a 13 % risk reduction of overall cancer mortality when comparing the highest versus lowest adherence to MD categories [11••].

Cancer Localizations

Breast Cancer

Five prospective cohort studies [18, 20, 43–45] and eight case–control studies [46–53] investigated the effects of conformity to an MD and risk of breast cancer. Pooling eight case–control studies resulted in a 10 % reduction of breast cancer incidence. However, pooling cohort studies (which are characterized by a higher level of evidence) did not confirm these results, i.e., none of the prospective cohort studies showed a significant inverse association between concordance to MD and breast cancer risk. Furthermore, we detected a trend for an association between high adherence to MD and reduced risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Differentiating breast cancer types as classified by receptor status yielded significant results when comparing the highest versus lowest adherence category to MD only for the ER−/PR+ type (relative risk (RR) 0.71, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.56 to 0.89) [11••].

Colorectal Cancer

Four prospective cohort studies [20, 54–56] and four case–control studies [19, 57–59] investigated the effects of adherence to MD and risk of colorectal cancer. Of these eight studies, two cohort and three case–control studies demonstrated a significant inverse association between adherence to MD and incidence of colorectal cancer. Following synthesis of all results via meta-analysis (excluding the study Tognon et al. 2012 on colorectal cancer mortality), a 17 % risk reduction for colorectal cancer could be detected when juxtaposing the highest versus lowest MD categories [11••].

Prostate Cancer

The risk of prostate cancer could be reduced by 4 % comparing the highest versus lowest adherence to MD category including four cohort studies [20, 60–62] and one case–control study [63].

Gastric Cancer

The EPIC study demonstrated a 33 % reduced risk of gastric adenocarcinoma following comparison of the third versus the first tertile of conformity to an MD [64]. Pooling all available cohort [64, 65•] and case–control [66] studies revealed a 27 % reduced risk of gastric cancer incidence [10••].

Liver Cancer

To date, only two studies (one cohort [67] and one case–control study [68]) investigated the effects of MD adherence on liver cancer risk. Both studies observed a significant inverse association (42 % reduced risk) [11••]

Esophageal Cancer

The NIH-AARP-cohort study including nearly 500,000 subjects showed a significant risk reduction for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (RR 0.44, 95 % CI 0.22 to 0.88), but not for esophageal adenocarcinoma [65•] in individuals adopting a MD pattern. An Italian case–control study reported a lower odds ratio for esophageal cancer in participants with high adherence to MD [69].

Head and Neck Cancer

Pooling one cohort study [70] and three case–control studies [69, 71, 72] in a meta-analysis resulted in a significantly reduced risk of head and neck cancer incidence (RR 0.40, 95 % CI 0.24 to 0.66) when comparing the highest versus the lowest categories of MD adherence. However, the data turned out to be non-significant in a sensitivity analysis considering only data from cohort studies [11••].

Pancreatic Cancer

Both a Swedish cohort study (pancreatic cancer mortality) [20] and an Italian case–control study [73] reported a significant inverse association between the highest concordance category to MD and pancreatic cancer risk. However, pooling these two studies resulted in a non-significant risk reduction, probably due to high between-study heterogeneity.

Ovarian, Bladder, and Endometrial Cancer

No significant association between adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of ovarian cancer could be observed in the Nurses’ Health Study [21]. Including 477,312 subjects from the EPIC study indicated a negative association between adherence to a MD pattern and risk of bladder cancer that was, however, non-significant [74]. Among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study, high conformity to MD (fifth vs. first quintile) was not significantly associated with risk of endometrial cancer [75]. In contrast, data from three case–control studies showed that high adherence (six to nine components) to MD correlated with a reduced odds ratio (OR 0.43) for endometrial cancer incidence [76], while a fourth case–control study from the USA did not confirm these protective effects of a MD [77].

Respiratory Tract Cancer

Two cohort studies investigated the effects of adherence to MD and risk of respiratory tract cancer [20, 78]. Pooling their data yielded a non-significant correlation between MD and reduction of respiratory tract cancer incidence [11••].

Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Cancer Survivors/Recurrence

The potential correlation between conformity to a high MD score and cancer mortality among cancer survivors was evaluated in three cohort studies [62, 79•, 80] while cancer recurrence among cancer survivors was assessed in one cohort study [81]. No significant association between MD and cancer mortality or cancer recurrence could be observed.

Diet Among Cancer Survivors

Tumor progression and recurrence as well as survival of cancer patients were shown to be affected by aspects of nutrition such as macronutrient composition or supplementation with specific nutrients, and some of these research studies have been transferred into recommendations and guidelines for cancer survivors [13, 14•]. Moreover, there are some studies dealing with the effects of food groups in cancer patients. A diet emphasizing fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and fish, but low amounts of red or processed meat and sugars, was associated with decreased mortality rates in cancer survivors [82–84]. Taken together, this description fits well with the characteristics of a Mediterranean diet. In the last part of this review, we will take a closer look at some of these components and their potential interactions with cancer development and progression focusing on data provided by systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Components of Mediterranean Diet and Cancer

Fruit and Vegetables

A protective effect of fruits and vegetables on cancer initiation and progression might be explained by their high content of flavonoids exerting favorable biological effects such as anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, or anti-proliferative properties [85]. Prospective cohort studies yielded inconsistent results regarding fruit and vegetable intake and cancer risk. Data from the EPIC cohorts provide evidence of at least a weak inverse association between high consumers and lower risk [86, 87]. However, these findings are not uniform as shown, e.g., by George et al. [88] following analysis of data from the cohort of the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. In a recent meta-analysis synthesizing data from 16 prospective cohort studies, a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables did correlate with a decrease in all-cause mortality, albeit not with a significant reduction in cancer-related death [85].

Fish

A higher consumption of fish is recommended especially due to its content of n-3 fatty acids. Via their anti-inflammatory effects, n-3 may suppress carcinogenesis and act in a protective manner against tumor initiation and progression. However, recent meta-analyses show rather inconsistent and inconclusive results with respect to inverse relationships between uptake of marine n-3 fatty acids or fish consumption and cancer incidence/mortality [89•, 90].

Whole Grain

Increased uptake of dietary fiber is regarded to be protective especially against the development of colorectal cancer, e.g., via an enlargement of the bulk of stool leading to a concomitant reduction in transit time thereby diminishing the impact of potential carcinogenic substances on the colonic epithelium. In addition, metabolization of fiber to short-chain fatty acids by intestinal bacteria may prevent dedifferentiation of colonic cells and support defense mechanisms against initiated cells by apoptosis [91]. In fact, there are a number of data from observational studies consistent with this hypothesis. Thus, consumption of whole grains and dietary fiber was inversely associated with risk of developing colorectal cancer in meta-analyses by Haas et al. [92] as well as Aune et al. [93]. Moreover, intervention and observational studies showed that dietary fiber is associated with reduced risk of insulin resistance [94, 95].

Olive Oil

Systematic analyses of epidemiological studies on the effects of olive oil on cancer development indicated decreased relative risks or odds ratios for breast cancer, cancers of the digestive system, or neoplasms of the respiratory tract [92]. Extra-virgin olive oil is rich in both monounsaturated fatty acids and in polyphenolic compounds such as tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, and oleuropein. It has been speculated that the phenolic content of extra virgin and virgin olive oil is able to specifically affect cancer-regulated oncogenes [96–98]. Furthermore, they may exert strong chemo-preventive effects via a variety of distinct mechanisms, including both direct anti-oxidant effects and actions on cancer cell signaling and cell cycle progression [99].

Alcohol and Red Wine in Moderate Amounts

Moderate consumption of alcohol in a MD is usually characterized by a threshold of <30 g ethanol/day for men and less than 20 g/day for women with a focus on red wine containing secondary plant substances such as polyphenols. These light amounts of alcohol were found to be associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease in a number of observational studies. On the other hand, alcoholic beverages providing ≥30 g ethanol/day are associated with increased risks of different cancers (e.g., cancers of the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, colorectum, breast, and liver) [100]. The effects of light alcohol drinking on cancer development and progression are still discussed controversially. While moderate consumption of less than 12.5 g ethanol/day was found to correlate with a decreased risk of cancer mortality when compared to non-drinkers [101•], the same amount of alcohol was reported to increase the risk of cancer for various locations in a meta-analysis by Bagnardi et al. [102].

Red and Processed Meat

Within the context of a MD, red and processed meat (and sometimes poultry) are regarded to be unfavorable compounds which should be consumed in low amounts. There is considerable evidence derived from meta-analyses linking high consumption of meat and/or processed meat with an increased risk of cancer mortality [103]. In addition, a meta-analysis of 21 observational studies presented by Xu et al. demonstrated that high consumption of red meat/processed meat is associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenomas [104].

Dairy Products

Different and sometimes contradictory results are reported with respect to consumption of milk and dairy products and the risk of cancer. In a recent report of two independent Swedish cohort studies, Michaelsson and co-workers [105] could demonstrate an increased adjusted hazard ratio for each glass of milk with respect to death caused by cancer in a female cohort. On the other hand, meta-analyzing the data available from cohort studies does not confirm a detrimental effect of dairy products. In contrast, milk and dairy product consumption was associated with a decreased relative risk for development of colorectal cancer [106], and total dairy food intake was found to be associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer [107].

Conclusion

It was the aim of the present review to summarize evidence provided by randomized and observational studies on the potential effects of a Mediterranean diet on cancer development, progression, and mortality. The data support the concept that a MD has a benefit with respect to these clinical outcomes, i.e., adherence to a MD was associated with reduced risk of overall cancer mortality as well as incidence of colorectal, breast, gastric, prostate, liver, and head and neck cancer. When dismantling the Mediterranean diet into its components, it seems that there is no single ingredient or food category mediating these favorable effects. It seems instead to be the result of the complex food pattern characteristic for a MD. However, one should keep in mind the limitations of and differences between the underlying studies. Apart from the problems stemming from the design of observational studies in general, a strong methodological issue is the wide variety of scores used to identify adherence to a MD. Nevertheless, taking into account the increasing number of observations reporting a beneficial effect of a Mediterranean diet in the primary and secondary prevention of other chronic diseases as well, it does not seem reasonable to exclude an MD pattern from dietary recommendations aimed at cancer prevention.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Mortality GBD, Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(5):1133–45. doi:10.1002/ijc.27711.

Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Kuper H, Trichopoulos D. Cancer and Mediterranean dietary traditions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9(9):869–73.

Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(6 Suppl):1402S–6S.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Mediterranean dietary pattern, inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases. NMCD. 2014;24(9):929–39. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.03.003. The present meta-analysis of 17 intervention trials showed that following a Mediterranean diet was associated with impovements in markers of endothelial function and inflammation.

Singh B, Parsaik AK, Mielke MM, Erwin PJ, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, et al. Association of Mediterranean diet with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis: JAD. 2014;39(2):271–82. doi:10.3233/JAD-130830.

Schwingshackl L, Missbach B, Konig J, Hoffmann G. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(7):1292–9. doi:10.1017/S1368980014001542.

Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1189–96. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29673.

Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1344.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer Int J Cancer. 2014;135(8):1884–97. doi:10.1002/ijc.28824. In this comprehensive meta-analysis of 1,4 million subjects, high adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of several types of cancer, especially colorectal and aerodigestive tract cancers.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Med (accepted). 2015. This updated meta-analysis of 56 observational studies confirmed a prominent and consistent inverse association provided by adherence to a Mediterranean Diet in relation to cancer mortality (10% reduced risk) and risk (only incidence) of several cancer types (colorectal, breast, liver, gastric, prostate, head and neck, pancreatic, and respiratory tract cancers).

DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–71. doi:10.3322/caac.21235.

Rowland JH, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Loge JH, Hjorth L, Glaser A, et al. Cancer survivorship research in Europe and the United States: where have we been, where are we going, and what can we learn from each other? Cancer. 2013;119 Suppl 11:2094–108. doi:10.1002/cncr.28060.

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–74. doi:10.3322/caac.21142. This report summarizes the current findings regardings lifeytle factors including nutrition and physical activity.

Jones LW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet, exercise, and complementary therapies after primary treatment for cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(12):1017–26. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70976-7.

Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist ML, Gnardellis C, Lagiou P, Polychronopoulos E, et al. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ. 1995;311(7018):1457–60.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–608. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025039.

Fung TT, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Newby PK, Willett WC, Holmes MD. Diet quality is associated with the risk of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2006;136(2):466–72.

Whalen KA, McCullough M, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean diet pattern scores and risk of incident, sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(11):1088–97. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu235.

Tognon G, Nilsson LM, Lissner L, Johansson I, Hallmans G, Lindahl B, et al. The Mediterranean diet score and mortality are inversely associated in adults living in the subarctic region. J Nutr. 2012;142(8):1547–53. doi:10.3945/jn.112.160499.

Xie J, Poole EM, Terry KL, Fung TT, Rosner BA, Willett WC, et al. A prospective cohort study of dietary indices and incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7(1):112. doi:10.1186/s13048-014-0112-4.

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med. 2007;44(4):335–40. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.12.009.

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Dietary patterns: a Mediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis: NMCD. 2006;16(8):559–68. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2005.08.006.

Gerber M. Qualitative methods to evaluate Mediterranean diet in adults. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(1A):147–51.

Goulet J, Lamarche B, Nadeau G, Lemieux S. Effect of a nutritional intervention promoting the Mediterranean food pattern on plasma lipids, lipoproteins and body weight in healthy French-Canadian women. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170(1):115–24.

Ciccarone E, Di Castelnuovo A, Salcuni M, Siani A, Giacco A, Donati MB, et al. A high-score Mediterranean dietary pattern is associated with a reduced risk of peripheral arterial disease in Italian patients with Type 2 diabetes. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(8):1744–52. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00323.x.

Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez JA, De Irala J, Martínez-González MA. Determinants of the adherence to an “a priori” defined Mediterranean dietary pattern. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41(6):249–57. doi:10.1007/s00394-002-0382-2.

Alberti-Fidanza A, Fidanza F, Chiuchiu MP, Verducci G, Fruttini D. Dietary studies on two rural italian population groups of the Seven Countries Study. 3. Trend Of food and nutrient intake from 1960 to 1991. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53(11):854–60.

de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Mamelle N, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1454–9.

Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. The PREDIMED study is the largest randomized controlled trial to date showing a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease following a Mediterranean Diet rich in extra virgin olive oil or nuts compared to a low fat diet.

Guasch-Ferre M, Bullo M, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ros E, Corella D, Estruch R, et al. Frequency of nut consumption and mortality risk in the PREDIMED nutrition intervention trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:164. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-164. The results of the largest MD trial, the PREDIMED study including 7447 subjects, showed that the highest category of nuts intake (>3 servings/week) was associated with a 40% risk reduction of cancer mortality when compared to the lowest category, whereas the differences observed between consumers of extra virgin olive oil did not attain statistical significance.

Guasch-Ferre M, Hu FB, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fito M, Bullo M, Estruch R, et al. Olive oil intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the PREDIMED Study. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):78. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-78. The results of the largest MD trial, the PREDIMED study including 7447 subjects, showed that the highest category of nuts intake (>3 servings/week) was associated with a 40% risk reduction of cancer mortality when compared to the lowest category, whereas the differences observed between consumers of extra virgin olive oil did not attain statistical significance.

Buckland G, Agudo A, Travier N, Huerta JM, Cirera L, Tormo MJ, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet reduces mortality in the Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Spain). Br J Nutr. 2011;106(10):1581–91. doi:10.1017/S0007114511002078.

Knoops KT, de Groot LC, Kromhout D, Perrin AE, Moreiras-Varela O, Menotti A, et al. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1433–9. doi:10.1001/jama.292.12.1433.

Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Sandin S, Lagiou A, Mucci L, Wolk A, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and mortality among young women: a cohort study in Sweden. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(2):384–92.

Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Guillen-Grima F, De Irala J, Ruiz-Canela M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beunza JJ, et al. The Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduction in premature mortality among middle-aged adults. J Nutr. 2012;142(9):1672–8. doi:10.3945/jn.112.162891.

Menotti A, Alberti-Fidanza A, Fidanza F, Lanti M, Fruttini D. Factor analysis in the identification of dietary patterns and their predictive role in morbid and fatal events. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(7):1232–9. doi:10.1017/S1368980011003235.

Harmon BE, Boushey CJ, Shvetsov YB, Ettienne R, Reedy J, Wilkens LR, et al. Associations of key diet-quality indexes with mortality in the Multiethnic Cohort: the Dietary Patterns Methods Project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(3):587–97. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.090688.

Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Li TY, Fung TT, Li S, Willett WC, et al. The Mediterranean-style dietary pattern and mortality among men and women with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):172–80. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.068106.

George SM, Ballard-Barbash R, Manson JE, Reedy J, Shikany JM, Subar AF, et al. Comparing indices of diet quality with chronic disease mortality risk in postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: evidence to inform national dietary guidance. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(6):616–25. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu173.

Vormund K, Braun J, Rohrmann S, Bopp M, Ballmer P, Faeh D. Mediterranean diet and mortality in Switzerland: an alpine paradox? Eur J Nutr. 2015;54(1):139–48. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0695-y.

Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Miller PE, Liese AD, Kahle LL, Park Y, et al. Higher diet quality is associated with decreased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality among older adults. J Nutr. 2014. doi:10.3945/jn.113.189407.

Buckland G, Travier N, Cottet V, Gonzalez CA, Lujan-Barroso L, Agudo A, et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet and risk of breast cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort study. Int J Cancer Int J Cancer. 2013;132(12):2918–27. doi:10.1002/ijc.27958.

Cade JE, Taylor EF, Burley VJ, Greenwood DC. Does the Mediterranean dietary pattern or the Healthy Diet Index influence the risk of breast cancer in a large British cohort of women? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(8):920–8. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2011.69.

Couto E, Sandin S, Lof M, Ursin G, Adami HO, Weiderpass E. Mediterranean dietary pattern and risk of breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055374.

Bessaoud F, Tretarre B, Daures JP, Gerber M. Identification of dietary patterns using two statistical approaches and their association with breast cancer risk: a case-control study in Southern France. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(7):499–510. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.006.

Castello A, Pollan M, Buijsse B, Ruiz A, Casas AM, Baena-Canada JM, et al. Spanish Mediterranean diet and other dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: case-control EpiGEICAM study. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(7):1454–62. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.434.

Demetriou CA, Hadjisavvas A, Loizidou MA, Loucaides G, Neophytou I, Sieri S, et al. The mediterranean dietary pattern and breast cancer risk in Greek-Cypriot women: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:113. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-113.

Mourouti N, Kontogianni MD, Papavagelis C, Plytzanopoulou P, Vassilakou T, Malamos N, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with lower likelihood of breast cancer: a case-control study. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(5):810–7. doi:10.1080/01635581.2014.916319.

Murtaugh MA, Sweeney C, Giuliano AR, Herrick JS, Hines L, Byers T, et al. Diet patterns and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: the Four-Corners Breast Cancer Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):978–84.

Nkondjock A, Ghadirian P. Diet quality and BRCA-associated breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(3):361–9. doi:10.1007/s10549-006-9371-0.

Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Stanczyk FZ, Pike MC. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(4):1145–54. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26915.

Pot GK, Stephen AM, Dahm CC, Key TJ, Cairns BJ, Burley VJ, et al. Dietary patterns derived with multiple methods from food diaries and breast cancer risk in the UK Dietary Cohort Consortium. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(12):1353–8. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.135.

Bamia C, Lagiou P, Buckland G, Grioni S, Agnoli C, Taylor AJ, et al. Mediterranean diet and colorectal cancer risk: results from a European cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(4):317–28. doi:10.1007/s10654-013-9795-x.

Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Rifai N, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):163–73.

Reedy J, Mitrou PN, Krebs-Smith SM, Wirfalt E, Flood A, Kipnis V, et al. Index-based dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(1):38–48. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn097.

Dixon LB, Subar AF, Peters U, Weissfeld JL, Bresalier RS, Risch A, et al. Adherence to the USDA Food Guide, DASH Eating Plan, and Mediterranean dietary pattern reduces risk of colorectal adenoma. J Nutr. 2007;137(11):2443–50.

Grosso G, Biondi A, Galvano F, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Buscemi S, et al. Factors associated with colorectal cancer in the context of the Mediterranean diet: a case-control study. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(4):558–65. doi:10.1080/01635581.2014.902975.

Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, Polychronopoulos E, Xinopoulos D, Linos A, et al. Metabolic syndrome and colorectal cancer: the protective role of Mediterranean diet--a case-control study. Angiology. 2012;63(5):390–6. doi:10.1177/0003319711421164.

Ax E, Garmo H, Grundmark B, Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Becker W, et al. Dietary patterns and prostate cancer risk: report from the population based ULSAM cohort study of Swedish men. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(1):77–87. doi:10.1080/01635581.2014.851712.

Bosire C, Stampfer MJ, Subar AF, Park Y, Kirkpatrick SI, Chiuve SE, et al. Index-based dietary patterns and the risk of prostate cancer in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(6):504–13. doi:10.1093/aje/kws261.

Kenfield SA, Dupre N, Richman EL, Stampfer MJ, Chan JM, Giovannucci EL. Mediterranean Diet and Prostate Cancer Risk and Mortality in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Eur Urol. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.009.

Möller E, Galeone C, Andersson T, Bellocco R, Adami HO, Andrén O, et al. Mediterranean Diet Score and prostate cancer risk in a Swedish population-based case-control study. J Nutr Sci. 2013;2:1–13.

Buckland G, Agudo A, Lujan L, Jakszyn P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Palli D, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(2):381–90. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28209.

Li WQ, Park Y, Wu JW, Ren JS, Goldstein AM, Taylor PR, et al. Index-based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Esophageal and Gastric Cancer in a Large Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1130–6. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.023. Data from the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study indicate that high adherence to Mediterranean diet was inveresely associated with risk for esophageal cancers, particularly esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Praud D, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Turati F, Ferraroni M, La Vecchia C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and gastric cancer risk in Italy. Int J Cancer Int J Cancer. 2014;134(12):2935–41. doi:10.1002/ijc.28620.

Li WQ, Park Y, McGlynn KA, Hollenbeck AR, Taylor PR, Goldstein AM, et al. Index-based dietary patterns and risk of incident hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality from chronic liver disease in a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014. doi:10.1002/hep.27160.

Turati F, Trichopoulos D, Polesel J, Bravi F, Rossi M, Talamini R, et al. Mediterranean diet and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):606–11. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.034.

Bosetti C, Gallus S, Trichopoulou A, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, et al. Influence of the Mediterranean diet on the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2003;12(10):1091–4.

Li WQ, Park Y, Wu JW, Goldstein AM, Taylor PR, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Index-based dietary patterns and risk of head and neck cancer in a large prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.073163.

Filomeno M, Bosetti C, Garavello W, Levi F, Galeone C, Negri E, et al. The role of a Mediterranean diet on the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(5):981–6. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.329.

Samoli E, Lagiou A, Nikolopoulos E, Lagogiannis G, Barbouni A, Lefantzis D, et al. Mediterranean diet and upper aerodigestive tract cancer: the Greek segment of the Alcohol-Related Cancers and Genetic Susceptibility in Europe study. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(9):1369–74. doi:10.1017/S0007114510002205.

Bosetti C, Turati F, Pont AD, Ferraroni M, Polesel J, Negri E, et al. The role of Mediterranean diet on the risk of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1360–6. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.345.

Buckland G, Ros MM, Roswall N, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Travier N, Tjonneland A, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of bladder cancer in the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer Int J Cancer. 2014;134(10):2504–11. doi:10.1002/ijc.28573.

George SM, Ballard-Barbash R, Shikany JM, Crane TE, Neuhouser ML. A prospective analysis of diet quality and endometrial cancer among 84,415 postmenopausal women in The Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(10):788–93 doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.05.009.

Filomeno M, Bosetti C, Bidoli E, Levi F, Serraino D, Montella M, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of endometrial cancer: a pooled analysis of three italian case-control studies. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(11):1816–21. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.153.

Dalvi TB, Canchola AJ, Horn-Ross PL. Dietary patterns, Mediterranean diet, and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control: CCC. 2007;18(9):957–66. doi:10.1007/s10552-007-9037-1.

Gnagnarella P, Maisonneuve P, Bellomi M, Rampinelli C, Bertolotti R, Spaggiari L, et al. Red meat, Mediterranean diet and lung cancer risk among heavy smokers in the COSMOS screening study. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO. 2013;24(10):2606–11. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt302.

Fung TT, Kashambwa R, Sato K, Chiuve SE, Fuchs CS, Wu K, et al. Post diagnosis diet quality and colorectal cancer survival in women. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115377. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115377. Higher adhernce to Mediterranean diet was not associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer or overall mortality in the Nurses Health Study among colorectal cancer survivors.

Kim EH, Willett WC, Fung T, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Diet quality indices and postmenopausal breast cancer survival. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(3):381–8. doi:10.1080/01635581.2011.535963.

Cottet V, Bonithon-Kopp C, Kronborg O, Santos L, Andreatta R, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal adenoma recurrence in a European intervention trial. Eur J Cancer Prev: Off J Eur Cancer Prev Organ (ECP). 2005;14(1):21–9.

Kroenke CH, Fung TT, Hu FB, Holmes MD. Dietary patterns and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9295–303. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0198.

Kwan ML, Weltzien E, Kushi LH, Castillo A, Slattery ML, Caan BJ. Dietary patterns and breast cancer recurrence and survival among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):919–26. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4035.

Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Hu FB, Mayer RJ, et al. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298(7):754–64. doi:10.1001/jama.298.7.754.

Arts IC, Hollman PC. Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(1 Suppl):317S–25S.

Benetou V, Orfanos P, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Boffetta P, Trichopoulou A. Vegetables and fruits in relation to cancer risk: evidence from the Greek EPIC cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2008;17(2):387–92. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-07-2665.

Boffetta P, Couto E, Wichmann J, Ferrari P, Trichopoulos D, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and overall cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(8):529–37. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq072.

George SM, Park Y, Leitzmann MF, Freedman ND, Dowling EC, Reedy J, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cancer: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):347–53. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26722.

Zheng J-S, Hu X-J, Zhao Y-M, Yang J, Li D. Intake of fish and marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of breast cancer: meta-analysis of data from 21 independent prospective cohort studies. 2013; 346. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3706. This meta-analysis showed that higher consumption of dietary marine n-3 PUFA is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer.

Han YJ, Li J, Huang W, Fang Y, Xiao LN, Liao ZE. Fish consumption and risk of esophageal cancer and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(2):147–54. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2012.213.

Williams MT, Hord NG. The role of dietary factors in cancer prevention: beyond fruits and vegetables. Nutr Clin Pract: Off Publ Am Soc Parenter Enter Nutr. 2005;20(4):451–9.

Haas P, Machado MJ, Anton AA, Silva ASS, de Francisco A. Effectiveness of whole grain consumption in the prevention of colorectal cancer: Meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60(s6):1–13. doi:10.1080/09637480802183380.

Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2011;343:d6617. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6617.

Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Pins JJ, Raatz SK, Gross MD, Slavin JL, et al. Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(5):848–55.

Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AFH. Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):439–42.

Sotiroudis TG, Kyrtopoulos SA. Anticarcinogenic compounds of olive oil and related biomarkers. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47 Suppl 2:69–72. doi:10.1007/s00394-008-2008-9.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:154. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-13-154.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):455–6. doi:10.7326/L14-5018-6.

Corona G, Spencer JP, Dessi MA. Extra virgin olive oil phenolics: absorption, metabolism, and biological activities in the GI tract. Toxicol Ind Health. 2009;25(4-5):285–93. doi:10.1177/0748233709102951.

World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007.

Jin M, Cai S, Guo J, Zhu Y, Li M, Yu Y, et al. Alcohol drinking and all cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(3):807–16. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds508. This meta-analysis of eighteen cohort studies indicated that light drinkers (≤12.5 g/day) had a 9% lower risk of cancer mortality compared with non/occasional drinkers, whereas heavy drinkers (≥50g/d) had a 31% increased risk.

Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(2):301–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds337.

O’Sullivan TA, Hafekost K, Mitrou F, Lawrence D. Food sources of saturated fat and the association with mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):e31–42. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301492.

Xu X, Yu E, Gao X, Song N, Liu L, Wei X, et al. Red and processed meat intake and risk of colorectal adenomas: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer Int J Cancer. 2013;132(2):437–48. doi:10.1002/ijc.27625.

Michaëlsson K, Wolk A, Langenskiöld S, Basu S, Warensjö Lemming E, Melhus H, Byberg L. Milk intake and risk of mortality and fractures in women and men: cohort studies. 2014; 349. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6015.

Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO. 2012;23(1):37–45. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr269.

Dong JY, Zhang L, He K, Qin LQ. Dairy consumption and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(1):23–31. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1467-5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Lukas Schwingshackl and Georg Hoffmann declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cancer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwingshackl, L., Hoffmann, G. Does a Mediterranean-Type Diet Reduce Cancer Risk?. Curr Nutr Rep 5, 9–17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0141-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0141-7