Abstract

Key message

Tetracentron sinense Oliver, an endangered species from China, displays a low within-population genetic diversity and high genetic differentiation among populations, and the existing populations could be divided into three conservation and management units.

Context

The endangered tree Tetracentron sinense Oliver has great value; however, little is known regarding the within-population genetic diversity and differentiation among T. sinense populations.

Aims

We examined the genetic diversity and differentiation of T. sinense wild populations, and we tested the effect of small-size population on the level of genetic diversity within these populations.

Methods

Using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), we assessed the genetic variation and structure among 174 individuals from 26 natural populations of T. sinense sampled across its distribution range in China.

Results

The ISSR primers yielded 180 amplified loci (123 were polymorphic). At the species level, the percentage of polymorphic loci (PPL), Nei’s gene diversity (H), and Shannon’s information index (I) were 68.3%, 0.196 and 0.300, respectively. The average population level PPL was 20.0%, and the Na, Ne, H, and I were 1.20, 1.13, 0.076, and 0.112, respectively. AMOVA revealed high genetic differentiation among populations (52.0% of total variance, P = 0.001), consistent with the gene differentiation coefficient (Gst = 0.607) and gene flow (Nm = 0.326). The 174 individuals of the 26 T. sinense populations clustered into three groups, and T. sinense geographic and genetic distance were significantly correlated.

Conclusions

T. sinense exhibited intermediate within-species genetic diversity, indicating preserved evolutionary potential. The low within-population genetic diversity and high genetic differentiation among T. sinense populations may be one of important factors causing endangerment. Three conservation units were determined based on genetic difference and structure. Inter-population introduction of individuals within units via appropriate propagation and seedling management might be an effective strategy for increasing T. sinense within-population genetic diversity and population size.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Tetracentron sinense Oliver, the only living species in the Tetracentraceae family, is mainly distributed in moist-temperate-deciduous or mixed evergreen and deciduous forests in central and southwest China (Fu and Bruce 1992). As an Arcto-Tertiary relict with a rich fossil record (Wu 2004), T. sinense is important for the study of ancient flora and the origin and evolution of angiosperms. Because of the high demand for medicinal (Wang et al. 2006), timber, and ornamental purposes (Zhang and Gao 1990), T. sinense has been subject to excessive destruction resulting in scattered distribution and poor regeneration. The climate change during the Quaternary ice age and human disturbances in recent years have resulted in a sharp decline in T. sinense population size, and its existing populations have consequently become small-sized (Frankel and Soulé 1981). Therefore, T. sinense is currently listed in Appendix III of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, https://cites.org/eng/node/41216), and is also listed as a National Second-grade Key Preserved Wild Plant in China (Fu 1992). Thus, collecting and conserving T. sinense germplasm resources is very urgent and necessary.

In recent years, sporogenesis and gametophyte development (Gan et al. 2012), pollination ecology (Gan et al. 2013), and seed and seedling ecology (Zhou 2007, Luo et al. 2010, Cao et al. 2012, Gan et al. 2012, 2013, Han et al. 2015, Li et al. 2015) have been studied to explore the causes of environment-related endangerment and suggest conservation strategies for the germplasm resources of T. sinense. Gan et al. (2013) have hypothesized that small population size limits the insect and wind pollination efficiency during T. sinense flowering and pollination, resulting in reduced genetic diversity within the population, which might be a crucial factor leading to species endangerment. However, to date, this hypothesis has not been confirmed by genetic diversity assessments.

Long-term preservation of endangered species requires the establishment of scientific conservation and management systems combining biological and environmental factors (Zhou et al. 2016). Genetic diversity is the basis for species evolution, and sufficient genetic variability is required for endangered species to evolve in response to changing environments (Frankel and Soulé 1981); thus, its maintenance is crucial for long-term survival and evolution (Stockwell et al. 2003, Yang et al. 2014). Therefore, knowledge regarding the genetic diversity and differentiation of the endangered plant T. sinense in different environments is a necessary prerequisite for a better understanding of the evolutionary history and endangerment mechanism of the species, as well as providing practical strategies for conservation and genetic management (Gordon et al. 2012, Gaafar et al. 2014, Lopes et al. 2014).

A series of genetic markers have been developed to analyze and evaluate the genetic diversity of endangered species. Compared with other genetic markers, DNA-based markers have superior reproducibility for the evaluation of genetic diversity (Gaafar et al. 2014). Sun et al. (2014) examined the phylogeography of T. sinense and described its current patterns of genetic diversity based on chloroplast DNA markers. However, because of slower evolutionary rates and insufficient polymorphism sites (Muir and Filatov 2007), maternally inherited chloroplast genes cannot accurately reveal the genetic variation within T. sinense populations without being combined with nuclear DNA markers; however, thus far, no studies have examined the genetic diversity within T. sinense populations based on nuclear DNA markers.

To date, a number of molecular markers related to the nuclear DNA have been used to examine genetic diversity. Among various marker systems, the inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) marker system is a technique that uses repeat-anchored primers to amplify DNA sequences between two inverted SSRs (Zietkiewicz et al. 1994, Culley and Wolfe 2001). By combining most of the benefits of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and SSR with the universality of Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Reddy et al. 2002), ISSR markers are reproducible under different conditions at a relatively low cost, and enable the use of higher primer annealing temperatures and the generation of longer sequences than other markers (Gaafar et al. 2014). ISSR markers have been successfully used to evaluate the genetic diversity of several endangered plant species (Lu et al. 2006, Tileye et al. 2007, Trindade et al. 2012, Zhang et al. 2013, Gaafar et al. 2014, Yang et al. 2014).

In this study, the genetic diversity and differentiation of 26 wild T. sinense populations were assessed using ISSR molecular markers. The aims of the study were (1) to assess the level of genetic diversity within populations and genetic differentiation among populations of T. sinense, (2) to test the effect of small-size population on the level of genetic diversity within these populations, and (3) to provide suggestions for conservation and management of T. sinense.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant species and sampled populations

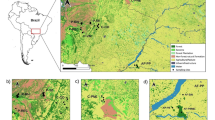

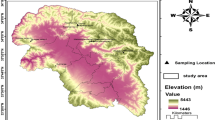

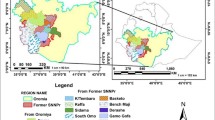

Samples were obtained from 174 individuals from 26 T. sinense populations across the T. sinense distribution range in China from July to August 2015 (Table 1; Fig. 1). Because of excessive destruction and poor regeneration, only a small sample size of these populations was available for this study. Thus, although only a small number of individuals in these populations were analyzed in this study, they can reflect the actual situation of this species. Fresh young leaves were collected, dried immediately with silica gel in zip-lock plastic bags, transported back to the laboratory, and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C. The sampled individuals were at least 50 m apart, to avoid sampling clonal individuals or individuals from the same family. Parameters such as longitude, latitude, altitude, and voucher number were recorded for each population (Table 1).

2.2 DNA extraction and detection

Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 80 mg of dry leaf materials using the no. LB1238 dry plant sample genome extraction kit (LABGENE Biotechnology, Chengdu, China). DNA was dissolved in 80 μl deionized water. Concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and integrity was determined by electrophoresis on 1.0% (w/v) agarose gels. The DNA was stored at − 20 °C until use.

2.3 ISSR-PCR amplification

ISSR primers (UBC primers 100, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada) were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biological Company. Fourteen polymorphic primers (Table 2) that produced clear and reproducible bands were selected for testing ISSR genetic diversity. The PCR reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl 2 × Taq PCR Master Mix, 0.6 μM primer, 70 ng genomic DNA, and double distilled water (to 12.5 μl), in a total volume of 25 μl. PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 70 s, annealing for 70 s, and DNA elongation at 72 °C for 1.5 min; and a final cycle of 70 s at 94 °C, 70 s at annealing temperature, and 5 min at 72 °C. Amplified products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. The 100 to 2000 bp DNA ladder (LABGENE Biotechnology) was used as a standard molecular weight. Photographs were taken using the UVP-gel documentation system (LABGENE Biotechnology).

2.4 Data analysis

The experiment was repeated three times to ensure accuracy, and only clear and reproducible bands were recorded. The bands were scored as present (1) or absent (0) for each sample, and a matrix of different ISSR phenotypes was assembled for data analysis (Yang et al. 2014). Parameters, including the percentage of polymorphic loci (PPL), observed number of alleles (Na), effective number of alleles (Ne), Nei’s gene diversity (H), Shannon’s information index (I), and total gene diversity (Ht), gene diversity within populations (Hs), coefficient of genetic differentiation (Gst = [Ht-Hs]/Ht), and gene flow among populations (Nm), were calculated to evaluate genetic diversity using the POPGENE1.32 software (Nei 1974, Wright, 1978, Yeh et al. 1997, Balloux and Lugonmoulin 2002). Each diversity index was compared among 26 populations using ANOVA and multiple comparison analysis, and the correlation between within-population genetic diversity and sample size was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis. Both analyses were conducted in SPSS statistic program v23.0.

For further estimation of the genetic variation among individuals within populations and among populations, DCFA and WINAMOVA 1.55 software were used for analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) (Excoffier et al. 1992, Zhang and Ge 2002). To determine the genetic relationships between the 26 T. sinense populations, the genetic structure of populations and individuals was obtained by UPGMA (unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means) cluster analysis using NTSYS software (Rohlf 2000). A Bayesian-clustering method based on the admixture model and correlated with the allele frequency, utilizing STRUCTURE version 2.3.3 (Pritchard et al. 2000), was also applied to infer how many clusters (K) were most appropriate for interpreting the data without prior information regarding the number of locations at which the individuals were sampled (Thriveni et al. 2014). All clusters derived from either cluster analysis or model-based structure analysis were also validated by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using the MVSP 32 program (Zhang et al. 2010). A Mantel test was performed to assess the correlation between geographic distance and genetic distance for the 26 populations using TFPGA software (Miller 1997, Wang et al. 2011).

2.5 Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/bhgan/Low-within-population-genetic-diversity-and-high-genetic-differentiation-among-populations-of-the-en [accessed 21 June 2018] or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

3 Results

3.1 ISSR polymorphisms

Fourteen primers that produced clear and reproducible amplicon profiles were chosen for genomic DNA amplification of all 174 individuals of the 26 T. sinense populations (Table 2). In total, 180 bright and discernible DNA fragments ranging in size from 100 to 2000 bp were scored, of which 123 bands (68.3%) were polymorphic among the 174 individuals, indicating that the average PPL was 68.3%. Bands and polymorphic bands per primer ranged from 7 to18 and 4 to 15, respectively. The PPL per primer ranged from 33.3 to 85.7%. As wild T. sinense individuals are rare, the amplification results of the samples in this experiment can reflect the actual genetic situation of the species.

3.2 Genetic diversity and differentiation

At the population level, the PPL ranged from 9.44 to 30.6% with an average of 20.0% (Table 3). H and I ranged from 0.041 to 0.122 and 0.059 to 0.177, respectively, with an average of 0.076 and 0.112, respectively. Na ranged from 1.094 to 1.306 with an average of 1.197. Ne ranged from 1.074 to 1.218 with an average of 1.134. The genetic diversity parameters differed among the 26 populations. The maximum values of the five abovementioned parameters were found in the P22 population, while the minimum values appeared in the P8 population. Overall, the genetic diversity of the P22, P6, P4, P15, and P2 populations was relatively high, while that of P9 and P8 was relatively low. ANOVA analysis showed that there were significant difference in within-population genetic diversity indices among the 26 T. sinense populations (P = 0.000 < 0.01, Table 3). All genetic diversity indices had a very significant positive correlation with sample size based on Pearson correlation analysis (Table 4). At the species level, the PPL, H, and I were 68.3%, 0.196, and 0.300, respectively (Table 4). Ht was 0.194 and the within-population gene diversity (Hs) was 0.076, which is < 50% of the Ht (Table 5).

The coefficient of genetic differentiation (Gst) and gene flow among populations (Nm) were 0.607 and 0.324, respectively (Table 5). AMOVA (Fig. 2) demonstrated extremely significant genetic differentiation among populations and within populations (P < 0.001); 52.0% of the total variation was due to differences among populations, while the remaining 48.0% was caused within-population differences.

3.3 Genetic structure

A dendrogram of the 26 populations was generated based on Nei’s genetic distances using UPGMA cluster analysis (Fig. 3). Using a genetic distance of 0.140, UPGMA analysis clustered the 26 populations into three groups. Group I included thirteen populations (P1, P6, P7, P11, P13, P14, P15, P16, P17, P20, P21, P22, and P23), group II consisted of nine populations (P2, P3, P4, P5, P10, P12, P18, P19, and P24), and the remaining four populations (P8, P9, P25, and P26) formed group III.

The genetic structure of 174 individuals from 26 populations was analyzed by structure analysis according to differences in allele frequency. Because 26 populations were examined in this study, the K value was set as 2 to 26. The relationship between the Ln P (D) value and K value was analyzed based on the methods described by Pritchard et al. (2000); however, no obvious inflection point was observed (Fig. 4a). Therefore, the ΔK value corresponding to each K value was further calculated based on the criteria reported by Evanno et al. (2005) and the related calculation formula (ΔK = M (|L (k + 1)−2 L(k) + L (k-1) | (/S) L (k)). As the maximum likelihood values showed a typical curvilinear response to increasing K (Fig. 4b), K = 3 (three groups) was defined to provide the optimal structure for further analysis. Structure cluster analysis showed that group I (blue) included fourteen populations (P1, P6, P7, P11, P12, P13, P14, P15, P16, P17, P20, P21, P22, and P23), group II (green) consisted of eight populations (P2, P3, P4, P5, P10, P18, P19, and P24), and the remaining four populations(P8, P9, P25, and P26) formed group III (red) (Fig. 4c). Topology was completely consistent with the PCoA plot (Fig. 5).

Results of genetic structure analysis of 174 individuals from 26 T. sinense populations. a The probability of the data Ln P(D) (± SD) against the number of K clusters. b ΔK values from the mean log-likelihood probabilities from STRUCTURE runs where inferred clusters (K) ranged from 2 to 26. c Estimated genetic clustering (K = 3) for 174 individuals from 26 populations

The Mantel test showed that there was an extremely significant correlation between genetic distance and geographic distance (r = 0.687, P = 0.001 < 0.01; Fig. 6).

4 Discussion

4.1 Genetic diversity within species and population level

In this study, the PPL of T. sinense at the species level was 68.33%, which was lower than the average value (PPL = 71.02%) based on 107 plant species (Nybom and Bartish 2000). A comparison with other endangered woody plants showed that the PPL of T. sinense was obviously higher than that of Loropetalum subcordatum (Benth.) Oliv. (PPL = 62.27%) (Gong et al. 2010), Ostrya rehderiana Chun (PPL = 29.90%) (Li et al. 2012), and Metrosideros boninensis Tuyama (PPL = 12.90%) (Shingo et al. 2010), but lower than that of Pteroceltis tatarinowii Maxim (PPL = 95.45%) (Li et al. 2013) and Tsoongiodendron odorum Chun (PPL = 79.67%) (Xu et al. 2014). These results indicate an intermediate level of within-species genetic diversity in T. sinense, and a relatively high level of genetic variation compared to other endangered woody plants.

The genetic diversity of species is the result of historical evolution and forms the basis for adaptation, survival, and evolution in changing environments (Stockwell et al. 2003, Yang et al. 2014). Abundant genetic variability can strengthen the ability of a species to respond to changing environments and consequently enhance its evolutionary potential. Genetic diversity is affected by many factors such as breeding system, seed dispersal, life form, geographical distribution, and historical origin (Hamrick et al. 1995, Nybom and Bartish 2000, Guo et al. 2016). Perennial plants with a longer life history usually demonstrate a higher level of genetic diversity compared to annual plants with a shorter life history (Nybom and Bartish 2000). As a tertiary relict plant (Fu and Bruce 1992), the long evolutionary history time scale of T. sinense has provided the possibility for gene mutation, recombination, and variation accumulation; in terms of spatial scale, the broad geographical distribution of T. sinense (Fu and Bruce 1992) has resulted in geographical isolation and habitat heterogeneity and thus increased genetic variation. The moderate within-species level genetic diversity of T. sinense indicates that this endangered species maintains a certain evolutionary potential.

The within-population level genetic diversity of T. sinense was obviously low compared to the within-species level. The PPL of the 26 T. sinense populations ranged from 9.44 to 30.56%, and the average was only 20.04%, indicating low level genetic variation within the populations. The gene diversity within populations (Hs = 0.076) was less than half of the total gene diversity (Ht = 0.194), suggesting that the genetic variation of T. sinense mainly existed among population, similar to the AMOVA analysis results. This result was also consistent with the cpDNA markers (Sun et al. 2014) and phenotypic traits (Han et al. 2017) results.

4.2 Genetic differentiation and structure

In population genetics, gene differentiation based on Gst values is classified as low (< 0.05), medium (0.05–0.15), or high (> 0.15). In the study, the Gst (0.607) and Nm (0.324) of T. sinense indicated a high level of genetic differentiation between populations and a low level of gene flow (Wright 1978, Balloux and Lugonmoulin 2002). The genetic diversity and structure of the plant populations were closely correlated with the following factors: the effective population size, breeding system, natural selection, and life history traits (including life form, ecological tolerance, seed dispersal, and gene flow) (Slatkin 1987, Hamrick and Godt 1990). For T. sinense, the growth characteristics of leafing out prior to flowering would hinder wind pollination to a certain extent; the rainy weather during flowering would restrict pollinator activity (Gan et al. 2013). These factors would promote selfing and inbreeding, which can increase the probability of homozygosity and reduce the probability of recombination, thus enhancing the similarity of individuals within a population and consequently increasing inter-population divergence (Loveless and Hamrick 1984). The relative statistical results showed that 51% of the total genetic variation in inbred species resulted from variation among populations (Gst = 0.510), which was more than five-fold that in outcrossing species (Gst = 0.099) (Hamrick and Godt 1990). Therefore, a breeding system mixed with selfing and outcrossing and shorter distance seed dispersal in T. sinense (Gan et al. 2013) had a negative impact on gene flow between individuals within populations or among populations, which eventually led to low level genetic variation within populations and high level genetic differentiation among populations.

It is generally believed that Nm > 1 is enough to inhibit genetic drift and prevent genetic differentiation among populations, while Nm < 1 is insufficient to counteract the effects of genetic drift, the dominant factor leading to genetic differentiation among populations (Slatkin 1985, Hamrick et al. 1995). For T. sinense, Nm was only 0.324, and there were significant differences in within-population genetic diversity among the 26 populations. Thus, small-size populations with remote geographical isolation due to the climate change during the Quaternary ice age and human disturbances (Frankel and Soulé 1981), contributed to a higher level of genetic drift and inbreeding, resulting in significant loss of genetic diversity within populations and an increase in genetic differentiation among populations (Ellstrand and Elam 1993, Freeland 2005, Willi et al. 2006). The Mantel Test showed that there was a significant correlation between geographic distance and genetic distance (r = 0.687, P = 0.001), indicating that geographical isolation played an important role in the high genetic differentiation of T. sinense among populations. Therefore, the small population effect and geographical isolation may constitute the main factors causing low genetic diversity within populations and high genetic differentiation among populations of T. sinense. As population is the basic unit of species evolution, the low within-population genetic diversity of T. sinense could reduce the adaptability to changing environments, which is not conducive to long-term survival and evolution. In this study, the correlation analysis showed that the level of within-population genetic diversity was significantly positively correlated with the small number of sampled trees, indicating that the sample size in each T. sinense populations has a very important limitation to within-population genetic variation analysis. Fine scale spatial genetic structure (SGS) data based on genetic analysis of all individuals within a population would be helpful for elucidating the actual population history, genetic variation, and underlying processes of the endangered plant T. sinense (Troupin et al. 2006), which needed to be further study.

The UPGMA and structure analyses both clustered the 26 T. sinense populations into three groups; this was further confirmed by the PCoA results. The extremely significant correlation between the geographic and genetic distance of T. sinense according to the Mantel test suggested a clear geographic tendency in the distribution of genetic variability. Notably, many neighboring populations clustered together so tightly that they were not obviously distinguishable in the PCoA plot (e.g., populations P4, P5, P10, P18, P19, and P24 in group II and populations P8, P9, P25, and P26 in group III). In contrast, the relationship between the populations in group I was relatively weak. Of the three groups, group III from the southwestern region of the Hengduan mountains is located in the southwestern zone of the T. sinense geographical distribution, group II from the eastern region of the Wuling mountains and northern region of the Qinling mountains is located in the northeastern zone of the geographical distribution, and group I is located between the Hengduan mountains and the Wuling or Qinling mountains in the central position (Fig. 1), suggesting obvious directional characteristics from southwest to northeast, which may be correlated with population recession to southwestern China (refuge) during the Quaternary ice age and population dispersion following the ice age (Sun et al. 2014). The three groups separated solely by the Hengduan, Qinling, and Wuling mountains, strongly indicate that geographical isolation played an important role in the genetic structure and distribution of T. sinense.

4.3 Implications for conservation

Our study results suggest that small populations due to human disturbance and habitat fragmentation (Gan et al. 2013) are an important cause of low genetic diversity within T. sinense populations; thus, the primary strategy should be to conduct in situ conservation to preserve all existing populations and their habitats. In particular, populations P22, P6, P4, P15, and P2 should be prioritized for in situ conservation because of their relatively higher within-population genetic variation. Moreover, germplasm resource banks of T. sinense should also be constructed via ex situ conservation and collection of genetic resources, in order to avoid the loss of genetic resources because of population degradation.

In the study, the existing T. sinense populations clustered into three groups based on genetic structure analysis, and small population size and geographical isolation played important roles in low gene flow among the populations. Therefore, each group should be considered as a conservation and management unit. For the three conservation units, inter-population introduction of individuals within units via appropriate propagation and seedling management might be an effective strategy for increasing within-population genetic diversity and population size of T. sinense (Frankham et al. 2002), especially for populations P8 and P9 because of their lower within-population genetic diversity.

5 Conclusions

Comprehensive molecular analysis showed that T. sinense is characterized by low genetic diversity within populations and high genetic differentiation among populations, which is attributed to small population effect and geographic isolation. However, the genetic diversity of T. sinense within species was at an intermediate level, indicating that T. sinense maintains a relatively higher evolutionary potential. Of course, this evolutionary potential may only be achieved by effective conservation strategies, such as in situ conservation for each population and its habitat, and inter-population introduction of individuals via appropriate propagation and seedling management between populations in order to increase the heterozygosity within T. sinense populations and the population size. The genetic structure obtained in this study will provide the scientific basis for these conservation efforts.

Abbreviations

- AFLP:

-

amplified fragment length polymorphisms

- cpDNA:

-

chroloplast DNA

- Gst :

-

coefficient of genetic differentiation

- H :

-

Nei’s gene diversity

- Hs:

-

gene diversity within populations

- Ht :

-

total gene diversity

- I :

-

Shannon’s information index

- ISSR:

-

inter-simple sequence repeat

- Na:

-

observed number of alleles

- Ne:

-

effective number of alleles

- Nm :

-

gene flow among populations

- PPL:

-

the percentage of polymorphic loci

- RAPD:

-

random amplified polymorphic DNA

- SGS:

-

spatial genetic structure

- SSR:

-

simple sequence repeat

References

Balloux F, Lugonmoulin N (2002) The estimation of population differentiation with microsatellite markers. Mol Ecol 11(2):155–165

Cao LL, Gan XH, He S (2012) Effect of different geographical provenances and matrix on seed germination and seeding initial growth of Tetracentron sinense. Guihaia 32:656–662

Culley TM, Wolfe AD (2001) Population genetic structure of the cleistogamous plant species Viola pubescens Aiton (Violaceae), as indicated by allozyme and ISSR molecular markers. Heredity 86(5):545–556

Ellstrand NC, Elam DR (1993) Population genetic consequences of small population size: implications for plant conservation. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 24:217–242

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14(8):2611–2620

Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM. (1992) Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metricdistances among DNA haplotypes:application to human mitochondrial-DNA restriction data. Genetics, 131:479–491

Frankel OH, Soulé ME (1981) Conservation and evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Briscoe DA (2002) Introduction to conservation genetics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Freeland JR (2005) Molecular ecology. John Wiley& Sons Ltd., West Sussex, pp 299–310

Fu LG (1992) Plant red book in China-rare and endangered plants (Book I). China Science Press, Beijing, pp 452–453–682–683

Fu DZ, Bruce B (1992) Tetracentron in Wu ZY and Raven PH. Flora of China. Science Press, Beijing, pp 590–591

Gaafar ARZ, AI-Qurainy F, Khan S (2014) Assessment of genetic diversity in the endangered population of Breonadia salicina (Rubiaceae) growing in The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using inter-simple sequence repeat markers. BMC Genet 15:109

Gan X, Xie D, Cao L (2012) Sporogenesis and development of gametophytes in an endangered plant, Tetracentron sinense Oliv. Biol Res 45(4):393–398

Gan XH, Cao LL, Zhang XM, Li H (2013) Floral biology, breeding system and pollination ecology of an endangered tree Tetracentron sinense Oliv. (Trochodendraceae). Bot Stud 54:50

Gong W, Gu L, Zhang D (2010) Low genetic diversity and high genetic divergence caused by inbreeding and geographical isolation in the populations of endangered species Loropetalum subcordatum (Hamamelidaceae) endemic to China. Conserv Genet 11:2281–2288

Gordon SP, Sloop CM, Davis HG, Cushman JH (2012) Population genetic diversity and structure of two rare vernal pool grasses in central California. Conserv Genet 13(1):117–130

Guo B, Lu D, Liao WB, Merilä J (2016) Genomewide scan for adaptive differentiation along altitudinal gradient in the Andrew’s toad Bufo andrewsi. Mol Ecol 25(16):3884–3900

Hamrick JL, Godt MJW (1990) Allozyme diversity in plant species. In: AHD B, Clegg MT, Kahler AL, Weir BS (eds) Plant population genetics, breeding, and genetic resources. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, pp 43–63

Hamrick JL, Godt MJW, Sherman-Broyles SL (1995) Gene flow among plant population: evidence from genetic markers. In: Hoch PC, Stephenson AG (eds) Experimental and Molecular Approaches to Plant Biosystematics. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, Saint Louis, pp 215–232

Han HY, Xu N, Li S et al (2015) The effect of low temperature during imbibition on germination characteristics of Tetracentron sinense (Tetracentraceae) seeds. Plant Div Res 37(5):586–594

Han H, Li S, Gan X, Zhang X (2017) Phenotypic diversity in natural populations of an endangered plant Tetracentron sinense. Bot Sci 95(2):283–294

Li YY, Guan SM, Yang SZ, Luo Y, Chen XY (2012) Genetic decline and inbreeding depression in an extremely rare tree. Conserv Genet 13:343–347

Li XH, Zhang H, Wang DY et al (2013) The genetic structure of endemic plant Pteroceltis tatarinowii by ISSR markers. Acta Ecol Sin 33(16):4892–4901

Li HC, Gan XH, Zhang ZP et al (2015) Effects of altitudes and the DBH of seed trees on biological characteristics of Tetracentron sinense (Tetracentraceae) seeds. Plant Div Res 37(2):177–183

Lopes MS, Mendonça D, Bettencourt SX, Borba AR, Melo C, Baptista C, da Câmara Machado A (2014) Genetic diversity of an Azorean endemic and endangered plant species inferred from inter-simple sequence repeat markers. AoB Plants 6:2016 (2014–6-26), 6

Loveless MP, Hamrick JL (1984) Ecological determinant of genetic structure in plant populations. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 15:65–95

Lu ZX, Wang YH, Peng YH, Korpelainen H, Li C (2006) Genetic diversity of Populus cathayana Rehd populations in southwestern China revealed by ISSR markers. Plant Sci 170:407–412

Luo JD, Gan XH, Jia XJ et al (2010) Biological characteristic of seeds of endangered plant Tetracentron sinense (Tetracentraceae). Acta Bot Yunnanica 32(3):204–210

Miller MP (1997) Tools for population genetic analysis. Version 1.3. Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff

Muir G, Filatov D (2007) A selective sweep in the chloroplast DNA of dioecious Silene (Section Elisanthe). Genetics 177:1239–1247

Nei M (1974) Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 70(12):3321–3323

Nybom H, Bartish IV (2000) Effects of life history traits and sampling strategies on genetic diversity estimates obtained with RAPD markers in plants. Perspect Plant Ecol 3(2):93–114

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155(2):945–959

Reddy MP, Sarla N, Siddiq EA (2002) Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica 128:9–17

Rohlf J (2000) NTSYS pc numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system, Version 2.1. Exeter publication, Setauket

Shingo K, Yuji I, Fuyuo N (2010) Genetic differentiation among populations of an oceanic island: the case of Metrosideros boninensis, an endangered endemic tree species in the Bonin Islands. Plant Spec Biol 23(2):119–128

Slatkin M (1985) Rare alleles as indicators of gene flow. Evolution 39:53–65

Slatkin M (1987) Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science (New York, NY) 236(4803):787–792

Stockwell CA, Hendry AP, Kinnison MT (2003) Contemporary evolution meets conservation biology. Trends Ecol Evol 18:94–101

Sun YX, Moore MJ, Yue LL, Feng T, Chu H, Chen S, Ji Y, Wang H, Li J (2014) Chloroplast phylogeography of the east Asian arcto-tertiary relict Tetracentron sinense (Trochodendraceae). J Biogeogr 41:1721–1732

Thriveni HN, Sumangala RC, Shivaprakash KN, Ravikanth G, Vasudeva R, Ramesh Babu HN (2014) Genetic structure and diversity of Coscinium fenestratum: a critically endangered liana of Western Ghats, India. Plant Syst Evol 300:403–413

Tileye F, Hilde N, Igorv B et al (2007) Analysis of genetic diversity in the endangered tropical tree species Hagenia abyssinica using ISSR markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol 54(5):947–958

Trindade H, Sena I, Goncalves S et al (2012) Genetic diversity of wild populations of Tuberaria major (Cistaceae), an endangered species endemic to the Algarve region (Portugal), using ISSR marker. Biochem Syst Ecol 45:9–16

Troupin D, Nathan R, Vendramin GG (2006) Analysis of spatial genetic structure in an expanding Pinus halepensis population reveals development of fine-scale genetic clustering over time. Mol Ecol 15:3617–3630

Wang YF, Lai GF, Efferth T, Cao JX, Luo SD (2006) New glycosides from Tetracentron sinense and their cytotoxic activity. Chem Biodivers 3(9):1023–1030

Wang J, Li Z, Guo Q, Ren G, Wu Y (2011) Genetic variation within and between populations of a desert poplar (Populus euphratica) revealed by SSR markers. Ann For Sci 68(6):1143–1149

Willi Y, Van Buskirk J, Hoffmann AA (2006) Limits to the adaptive potential of small populations. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37:433–458

Wright S (1978) Evolution and the genetics of populations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wu ZY (2004) Flora of China (book 1). Science Press, Beijing

Xu GB, Wu XQ, Jiang GX et al (2014) Genetic diversity and population structure of an endangered species: Tsoongiodendron odorum Chun. J Plant Gen Res 15(2):255–261

Yang Q, Fu Y, Wang YQ, Wang Y, Zhang WH, Li XY, Reng YQ, Zhang J (2014) Genetic diversity and differentiation in the critically endangered orchid (Amitostigma hemipilioides): implications for conservation. Plant Syst Evol 300:871–879

Yeh FC, Yang RC, Boyle T (1997) POPGENE, version 1.32 ed. Software Microsoft Window-based freeware for population genetic analysis. University of Alberta, Edmonton

Zhang P, Gao SZ (1990) Wood anatomy of Tetracentraceae. Acta Botan Boreali-Occiden Sin 10(3):185–189

Zhang FM, Ge S (2002) Data analysis in population genetics. I. Analysis of RAPD data with AMOVA. Biodivers Sci 10(4):438–444

Zhang DD, Bai GH, Zhu CS, Yu J, Carver BF (2010) Genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium in U.S. elite winter wheat. Plant Genome 3(2):117

Zhang QX, Shen YK, Shao RX, Fang J, He YQ, Ren JX, Zheng BS, Chen GJ (2013) Genetic diversity of natural Miscanthus sinense populations in China revealed by ISSR markers. Biochem Syst Ecol 48:248–256

Zhou YX (2007) Light requirement characteristics for the germination of Tetracention sinense Oliv seeds. J Cent South Univ For Technol27:54–57

Zhou ZM, Newman C, Buesching CD, Meng X, Macdonald DW, Zhou Y (2016) Revised taxonomic binomials jeopardize protective wildlife legislation. Conserv Lett 9(5):313–315

Zietkiewicz E, Rafalski A, Labuda D (1994) Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (SSR)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics 20:176–183

Acknowledgements

We thank the following peoples in each Nature Reserve Authority (NRA) for sample collecting: Zhirong Gu and Guorong Wei in Badagongshan NRA and Longping Tang in Sunhuangshan NRA of Hunan province, Shuanzhu Dong in Taibaishan NRA of Shanxi province, Liming Chen in Tangjiahe NRA and Dahai Zhu in Longxi-Hongkou NRA of Sichuan province, Aicai Nie in Wufeng Houhe NRA of Hubei province, and Ma in Baishuijiang NRA of Gansu province.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.31370367), the Applied Basic Research Project of Sichuan Province, China (No.2017JY0164) and the Meritocracy Research Funds of China West Normal University (No. 17YC325).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The State Forestry Administration of the People’s Republic of China granted permissions to Professor Xiaohong Gan for using the endangered species of plant (Tetracentron sinense).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Ricardo Alia

Contribution of the co-authors

Xiaohong Gan conceived the project, designed the experiments, and performed the experiment partly; Shan Li wrote the manuscript and performed the experiment; and Hongyan Han, Xuemei Zhang, and Zongqiong Tian performed the experiment and statistical analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Gan, X., Han, H. et al. Low within-population genetic diversity and high genetic differentiation among populations of the endangered plant Tetracentron sinense Oliver revealed by inter-simple sequence repeat analysis. Annals of Forest Science 75, 74 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-018-0752-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-018-0752-4