Abstract

Introduction

5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3RAs) are the most commonly recommended agents for the prophylaxis of radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV) within international antiemetic guidelines. However, the optimal timing and duration of their administration is unknown. We reviewed the relevant literature as a first step in addressing this important issue in supportive care.

Methods

EMBASE and EMBASE Classic, Ovid MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for articles reporting on patient cohorts receiving prophylactic therapy with a 5-HT3RA and being prospectively evaluated for RINV. Cohorts were grouped into high-, moderate-, and low-emetic-risk categories according to international guidelines.

Results

The search identified 599 references, and 25 were included in the review. These contained 33 discrete patient cohorts (cumulative n = 1,067) that were prospectively evaluated for RINV while receiving prophylactic 5-HT3RA therapy. Of the 11 high-emetic-risk radiotherapy cohorts, two, eight, and one received 5-HT3RAs for durations longer than, equal to, or shorter than the duration of radiotherapy, respectively. Of the 22 moderate or low-emetic-risk radiotherapy cohorts, 5, 14, and 3 received 5-HT3RAs for durations longer than, equal to, or shorter than the duration of radiotherapy, respectively. Radiotherapy regimens and study endpoints were heterogeneous, precluding statistical comparisons of prophylaxis strategies.

Conclusion

5-HT3RAs were most commonly administered for the entire duration of a course of radiotherapy. Future studies should compare different timings and durations of therapy with common efficacy endpoints to develop effective and cost-efficient antiemetic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 40–80% of patients receiving radiotherapy will develop radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV), depending on the anatomic region being treated [1–4]. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3RAs; e.g., ondansetron, granisetron) are the most commonly recommended agents for the prevention of RINV within major practice guidelines [1, 5, 6]. However, the optimal timing and duration of administration for these agents in relation to the duration of a course of radiotherapy is unknown, and recommendations vary between these guidelines (Table 1). The studies upon which they are based involved both single- and multiple-fraction radiotherapy regimens of different emetic risks, and they administered 5-HT3RAs for different durations: (1) during the entire course of radiotherapy as well as a period of time afterwards (extended duration prophylaxis), (2) during the entire course of radiotherapy alone (equal duration prophylaxis), and (3) during only the early stages of a fractionated course of radiotherapy (shortened duration prophylaxis).

The issue of optimal timing and duration is important, as preclinical and clinical data suggest that 5-HT3RAs may lose their antiemetic effectiveness beyond the first 24–48 h following radiotherapy initiation [7–9]. Human and animal studies suggest that the mechanisms underlying RINV [10, 11] are similar to those underlying chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). For CINV, serotonin (5-HT) is considered to mediate the acute emetic response during the first 24 h following cytotoxic chemotherapy but not the delayed emetic response that follows. As a result, 5-HT3RAs are typically only recommended for the first day of a course of emetogenic chemotherapy. It is not clear if every fraction of radiotherapy can induce its own ‘acute’ response, or if the 5-HT system exhausts itself during the first few fractions of a fractionated course. Delayed nausea and vomiting occurring following radiotherapy completion or during the latter stages of a fractionated course could be due to mechanisms unrelated to 5-HT that would not benefit from prolonged 5-HT3RA therapy [1, 9, 11].

If the optimal timing and duration of administration for these agents was known, patients, radiation oncologists, and third-party payers could make more informed decisions regarding the relative benefits, toxicities, and costs associated with prophylactic 5-HT3RA therapy. As no randomized trials have compared different timings or durations of prophylaxis, this review aimed to summarize the data pertaining to 5-HT3RA timing and duration available in the literature as a first step in addressing the issue.

Methods

Search strategy

The intent of the study was discussed with a medical librarian who then searched:

EMBASE and EMBASE Classic (1947 to week 7, 2011), Ovid MEDLINE (1948 to week 3 February 2011), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005 to February 2011), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (first quarter 2011), for English-language human subject references while using permutations of the following subject headings and keywords: radiation, radiotherapy, induce, nausea, vomit, emesis. The abstracts or available data from the references produced by this search were read independently by two authors (KD, LM) to select references for full article review according to pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included any published journal articles reporting on randomized or non-randomized adult patient cohorts receiving prophylactic therapy with a 5-HT3RA and being prospectively evaluated with respect to RINV. Abstracts or available data returned in the search that did not clearly identify a patient population, study design, or pharmacological intervention were still included for full article review to be conservative. The abstracts from articles within the reference lists of articles meeting the inclusion criteria were searched according to the same inclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included duplicate references, references from different journal articles that described the same research study, conference abstracts, references clearly describing only rescue rather than prophylactic therapy, references clearly describing only non-5-HT3RA anti-emetic therapy, studies clearly defined as not being prospective, and studies not reporting nausea and vomiting outcomes as a function of 5-HT3RA therapy. These strict criteria allowed us to justify the inclusion of both randomized and non-randomized studies as they controlled for the most important potential sources of selection and measurement bias.

Final selection and data abstraction

The full articles from references that met the inclusion criteria but avoided exclusion criteria were read independently by two authors (KD, LM) to definitively identify for final selection those studies with inclusion criteria and without exclusion criteria. Discrepancies between KD and LM for final selection or data abstraction from the selected articles were to be resolved through consensus. Data abstracted from selected studies included author and citation information, study design (randomized or non-randomized), radiotherapy and concurrent anti-cancer therapy details, 5-HT3RA and co-antiemetic administration details, and the cumulative proportions of patients experiencing no nausea or vomiting respectively (i.e., cumulative complete response (CR) rates for nausea and vomiting). These cumulative CR rates were chosen as the primary outcomes of interest as they were considered to be the most clinically important and the most likely endpoints to be found (at least in part) within most studies, given the known heterogeneity of endpoint reporting [12]. The working definition of a CR for nausea was no nausea and no use of rescue anti-emetic medication during a specified study period. The working definition of a CR for vomiting was no vomiting and no use of rescue anti-emetic medication during a specified study period. When these endpoints were not available, the endpoints most closely approximating them were recorded. When details were not clear, authors from references were contacted. Intention-to-treat figures were used when reported.

Studies were first grouped according to the emetogenic risk of the radiotherapy involved as defined by the guidelines of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/European Society of Medical Oncology (MASCC/ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [1, 5]. High-risk radiotherapy was defined as total body irradiation (TBI). Moderate-risk radiotherapy was defined as: upper abdominal, hemi-body, or upper-body irradiation. Low-risk radiotherapy was defined as: cranial, craniospinal, head and neck, lower thorax, or pelvic irradiation. Studies were then grouped according to whether they administered single or multiple fraction radiotherapy and then by whether their duration of 5-HT3RA prophylaxis was longer than, equal to, or shorter than their duration of radiotherapy (extended-, equal-, or shortened duration prophylaxis).

Results

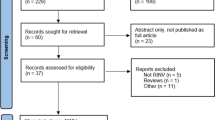

The initial literature search produced 599 references. The abstracts or available data from 57 of these initially satisfied the inclusion criteria, and their full articles were obtained. Thirty-two of the 57 were excluded after reading the full articles for the following reasons: being conference abstracts only, being articles from different journals describing the same study with no unique data, being review or retrospective but not prospective studies, being studies of chemotherapy alone, or being studies not administering prophylactic therapy. Twenty-five studies were left to form the basis of the review (Table 2). No final selection discrepancies between KD and LM occurred. Authors for two studies [13, 24] were contacted, and clarification of details was received in full. All 25 studies involved patients with a diagnosis of malignancy. One also included a single patient with aplastic anemia [13], and another included patients with aplastic anemia within its eligibility criteria, but it was unclear if such patients were included in the final analysis [14]. Twenty studies were published between the years 1990–1999, and five were published from 2000 onward. Sixteen were randomized studies, and nine were non-randomized.

In total, there were 33 discrete patient cohorts identified from the 25 studies, and these cohorts cumulatively contained 1,067 patients. Five different 5-HT3RAs were identified among the cohorts, with 15 cohorts receiving therapy intravenously and 18 orally. Eight of the 25 final studies described high emetic risk radiotherapy, and they cumulatively contained 11 discrete patient cohorts prospectively evaluated for RINV while receiving prophylactic 5-HT3RA-containing therapy: Two cohorts received them for a duration longer than the duration of radiotherapy, eight received them for a duration equal to that of radiotherapy, and one received them for a duration shorter than that of radiotherapy. Of the remaining 17 of 25 final studies, 12 described moderate-risk radiotherapy only one described low risk radiotherapy, and four described a mix of moderate- and low-risk radiotherapy with the majority of patients within these four cohorts receiving moderate risk treatment. These 17 remaining studies cumulatively contained 22 discrete patient cohorts: 5, 14, and 3 of these received extended-, equal-, or shortened duration prophylactic 5-HT3RA-containing therapy respectively.

Nausea and vomiting endpoints varied greatly. The data extracted from each of the 33 cohorts that most closely approximated our review’s primary endpoints of cumulative complete response rate data for nausea and vomiting are listed in Table 2.

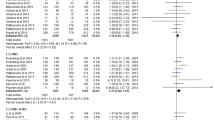

Twenty-four of the 33 cohorts (73%) reported some amount of cumulative complete response rate data for nausea [13–26, 28–30], and 28 of 33 cohorts (85%) did so for vomiting [10, 13–20, 22–26, 28–33]. These cohorts are shown in Table 3 where they are grouped according to emetogenic risk (high vs moderate/low), radiotherapy fractionation (single vs multiple), and duration of prophylaxis (extended, equal or shortened). If only whole-cohort daily incidence rates of nausea and vomiting were reported rather than cumulative rates for the entire radiotherapy course, only the first day’s complete response rate data was used.

High-emetic-risk single-fraction cohorts with extended duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 1) of 81% and vomiting (n = 1) of 81%, while those cohorts with equal duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 2) of 67% and 90% and for vomiting (n = 4) ranging from 50% to 90%. High-emetic-risk multiple-fraction cohorts with equal duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 3) ranging from 11% to 40% and for vomiting (n = 4) ranging from 27% to 50% (Table 3).

Moderate- and low-emetic-risk single-fraction cohorts with extended duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 2) of 70% and 73% and vomiting (n = 1) of 97%, while those cohorts with equal duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 6) ranging from 54% to 100% and for vomiting (n = 7) ranging from 58% to 100%. Moderate- and low-emetic-risk multiple fraction cohorts with extended duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 3) ranging from 31% to 46% and for vomiting (n = 3) ranging from 59% to 79%, while those cohorts with equal duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 4) ranging from 20% to 79% and for vomiting (n = 5) ranging from 58% to 91%, and those cohorts with shortened duration prophylaxis had CR rates for nausea (n = 3) ranging from 38% to 100% and for vomiting (n = 3) ranging from 71% to 100% (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first review of RINV studies specifically focusing on the timing and duration of prophylactic 5-HT3RA therapy. Research in the past has focused more on finding an optimal dose for these agents [37] and comparing them to other anti-emetics [38] than on determining their optimal timing or duration of administration [9].

Including both randomized and non-randomized studies was necessary given the limited and shrinking amount of data in RINV 5-HT3RA research. Indeed, the number of selected studies from the year 2000 onward was only a quarter of that from the decade prior; a disturbing trend when one considers the many unanswered questions pertaining to 5-HT3RA anti-emetic therapy. This review was able to include valuable data that had been excluded from previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses which focused on only randomized studies [8, 38].

Regardless of the emetic risk of the radiotherapy employed, 5-HT3RAs were most commonly administered from the time of the first radiotherapy fraction to the time of the last fraction. Prophylactic therapy of this timing and duration fits with a hypothesis that, at least a component of all RINV is mediated through the 5-HT system, that this process is ongoing for the entire course of radiotherapy regardless of the fractionation, and that the process stops immediately following radiotherapy. No conclusions could be made regarding patterns of administration during non-treatment days within this period (e.g., weekends and holidays) as these details were not consistently reported. Only a minority of studies administered therapy for durations longer or shorter than the course of radiotherapy (Table 2).

Despite our broad search criteria that identified 1,067 total patients from 33 discrete cohorts, formal statistical comparisons of different 5-HT3RA therapy durations could not be made. Reasons for this include the need to divide these patients into smaller meaningful comparison groups to control for radiotherapy emetic risk and fractionation, as well as the heterogeneity of efficacy endpoint reporting.

However, some potential trends were identified in those studies reporting cumulative complete response rate data (Table 3). For high-emetic-risk single-fraction radiotherapy, the single study using extended duration prophylaxis [15] had numerically superior control rates for both nausea and vomiting during the 12 h following radiotherapy completion compared with the four studies using equal duration prophylaxis. For moderate- and low-emetic-risk single-fraction radiotherapy, compared with the cohorts using extended and equal duration prophylaxis, the two cohorts from a large study using shortened duration prophylaxis [29] had numerically inferior control rates for both nausea and vomiting during the period of radiotherapy when no prophylaxis was being administered.

Other factors beyond limited data urge caution when interpreting the results of this review and their relevance to optimal therapy timing and duration. 5-HT3RAs were administered via both IV and PO routes, and five different agents were employed. Although in general these agents are considered to be equally efficacious, there are important pharmaco-dynamic differences among them that could influence their ideal duration of administration, especially during single-fraction radiotherapy. Whereas granisetron and tropisetron bind irreversibly to the 5-HT3 receptors and can show significant antiemetic activity up to 48 h following administration, ondansetron binds reversibly to the receptor, it can be displaced by exogenous 5-HT, and it can lose antagonist activity at the receptor by 24 h following administration of commonly employed doses [37, 39].

Efficacy endpoint heterogeneity was another factor. Not all studies reported both nausea and vomiting outcomes, and the times at which these events were captured ranged from immediately following radiotherapy initiation to 3 days following treatment completion. The use of rescue medications was variably reported, and not all studies were clear regarding their impact on efficacy endpoints. Some studies reported nausea and vomiting rates as the proportions of total treatment days (shared between all patients within a cohort) during which events occurred. Others reported only daily incidence rates rather than cumulative incidence rates. Co-antiemetics were administered with 5-HT3RAs in some studies, and finally, although very few studies administered chemotherapy and radiotherapy on the same day, some of the cohorts received chemotherapy in the days prior to TBI which likely influenced rates of nausea and vomiting.

The latest antiemetic guideline from ASCO [5] recommends a 5-HT3RA prior to each fraction of radiotherapy for patients within their moderately emetic risk group (which includes patients receiving upper abdominal radiotherapy) and for at least 24 h after the last fraction as well for patients within their high-emetic-risk group (those receiving TBI). Similarly, the anti-emesis guideline of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends a 5-HT3RA prior to each fraction for patients receiving TBI or upper abdominal/localized site irradiation [6]. By comparison, the latest guideline from MASCC/ESMO makes no specific recommendation regarding the duration of 5-HT3RA therapy for patients within their moderate-emetic-risk group (which includes those receiving upper abdominal irradiation) [1]. Informally comparing the cumulative complete response rate data from our review provides support neither for nor against using these agents for the entire duration of a fractionated radiotherapy course. The data do, however, confirm the existence of delayed RINV, as complete response rates for the entire duration of fractionated regimens were consistently low, especially for nausea. The same held true for single fraction treatments, where nausea and vomiting were commonly detected in the days following irradiation.

5-HT3RAs are costly to patients and third-party payers and have a well-known side effect profile that includes headache, constipation, diarrhoea, asthenia, and dizziness. However, despite some possible trends, it is not clear from our review that the efficacy of prolonged administration in preventing RINV warrants placing patients at risk for these side effects for such a duration. This is an especially important consideration for the palliative setting where the goals of care are improving quality of life and relieving symptoms.

Future studies should compare different durations of 5-HT3RA administration using standardized efficacy endpoints that control for rescue anti-emetics and that allow for evaluations of both nausea and vomiting during and following courses of single- and multiple-fraction radiotherapy. Cumulative incidence rates should be reported in addition to daily incidence rates or proportions of total treatment days. Given the literature suggesting a limited benefit for these agents beyond the acute setting, short-duration cohorts should be included in such studies.

Conclusion

Although research into 5-HT3RAs for the prevention of RINV has declined over the past decade, there remain important and methodologically simple questions that should be answered. The optimal timing and duration of often costly 5-HT3RA therapy has not been studied; a gap in our knowledge that has toxicity implications for patients and cost implications for both patients and third-party payers.

References

Feyer PC, Maranzano E, Molassiotis A, Roila F, Clark-Snow RA, Jordan K (2011) Radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV): MASCC/ESMO guideline for antiemetics in radiotherapy: update 2009. Support Care Cancer 19(Suppl 1):S5–S14

Enblom A, Bergius AB, Steineck G, Hammar M, Borjeson S (2009) One third of patients with radiotherapy-induced nausea consider their antiemetic treatment insufficient. Support Care Cancer 17(1):23–32

The Italian Group for Antiemetic Research in Radiotherapy (1999) Radiation-induced emesis: a prospective observational multicenter Italian trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 44(3):619–625

Maranzano E, De Angelis V, Pergolizzi S et al (2010) A prospective observational trial on emesis in radiotherapy: analysis of 1020 patients recruited in 45 Italian radiation oncology centres. Radiother Oncol 94:36–41

Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ et al (2011) Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 29(31):4189–4198

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2011) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Antiemesis. V.3.2011. http://www.nccn.org/clinical.asp. Accessed 12 December 2011

Bermudez J, Boyle EA, Miner WD, Sanger GJ (1988) The anti-emetic potential of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor antagonist BRL 43694. Br J Cancer 58:644–650

Tramer MR, Reynolds DJM, Stoner NS, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (1998) Efficacy of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review. Eur J Cancer 34(12):1836–1844

de Wit R, Aapro M, Blower PR (2005) Is there a pharmacological basis for differences in 5-HT3-receptor antagonist efficacy in refractory patients? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 56:231–238

Scarantino CW, Ornitz RD, Hoffman LG, Anderson RF (1994) On the mechanism of radiation-induced emesis: the role of serotonin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 30(4):825–830

Yamamoto K, Takeda N, Yamatodani A (2002) Establishment of an animal model for radiation-induced vomiting in rats using pica. J Radiat Res 43:135–141

Olver I, Molassiotis A, Aapro M, Herrstedt J, Grunberg S, Morrow G (2011) Antiemetic research: future directions. Support Care Cancer 19(Suppl 1):S49–S55

Spitzer TR, Bryson JC, Cirenza E et al (1994) Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of oral Ondansetron in the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with fractionated total-body irradiation. J Clin Oncol 12:2432–2438

Spitzer TR, Friedman CJ, Bushnell W, Frankel SR, Raschko J (2000) Double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study on the efficacy and safety of oral Granisetron and oral Ondansetron in the prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting in patients receiving hyperfractionated total body irradiation. Bone Marrow Transplant 26:203–210

Belkacemi Y, Ozsahin M, Pene Francoise P et al (1996) Total body irradiation prior to bone marrow transplantation: efficacy and safety of Granisetron in the prophylaxis and control of radiation-induced emesis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 36(1):77–82

Tiley C, Powles R, Catalano J et al (1992) Results of a double blind placebo controlled study of ondansetron as an antiemetic during total body irradiation in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma 7:317–321

Franzen L, Nyman J, Hagberg H et al (1996) A randomised placebo controlled study with Ondansetron in patients undergoing fractionated radiotherapy. Ann Oncol 7:587–592

Henriksson R, Lomberg H, Israelsson G, Zackrisson B, Franzen L (1992) The effect of ondansetron on radiation-induced emesis and diarrhoea. Acta Oncol 31(7):767–769

Priestman TJ, Roberts JT, Lucraft H et al (1990) Results of a randomized double-blind comparative study of ondansetron and metoclopramide in the prevention of nausea and vomiting following high-dose upper abdominal irradiation. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2:71–75

Priestman TJ, Roberts JT, Upadhyaya BK (1993) A prospective randomized double-blind trial comparing ondansetron versus prochlorperazine for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing fractionated radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 5:358–363

Sykes AJ, Kiltie AE, Stewart AL (1997) Ondansetron versus a chlorpromazine and dexamethasone combination for the prevention of nausea and vomiting: a prospective, randomised study to assess efficacy, cost effectiveness and quality of life following single-fraction radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 5:500–503

Bey P, Wilkinson PM, Resbent M et al (1996) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of i.v. dolasetron mesilate in the prevention of radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 4:378–383

Bodis S, Alexander E, Kooy H, Loeffler JS (1994) The prevention of radiosurgery-induced nausea and vomiting by ondansetron: evidence of a direct effect on the central nervous system chemoreceptor trigger zone. Surg Neurol 42:249–252

Khoo VS, Rainford K, Horwich A, Dearnaley DP (1997) The effect of antiemetics and reduced radiation fields on acute gastrointestinal morbidity of adjuvant radiotherapy in stage I seminoma of the testis: a randomized pilot study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 9:252–257

Lanciano R, Sherman DM, Michalski J, Preston AJ, Yocom K, Friedman C (2001) The efficacy and safety of once-daily Kytril (granisetron hydrochloride) tablets in the prophylaxis of nausea and emesis following fractionated upper abdominal radiotherapy. Cancer Invest 19(8):763–772

Logue JP, Magee B, Hunter RD, Murdoch RD (1991) The antiemetic effect of granisetron in lower hemibody radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 3:247–249

Maisano R, Pergolizzi S, Settineri N (1998) Escalating dose of oral ondansetron in the prevention of radiation induced emesis. Anticancer Res 18:2011–2014

Mystakidou K, Kouloulias V, Nikolaou V et al (2010) A comparative study of prophylactic antiemetic treatment in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. J BUON 15:29–35

Wong RKS, Paul N, King K et al (2006) 5-Hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist with or without short-course dexamethasone in the prophylaxis of radiation induced emesis: a placebo-controlled randomised trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (SC19). J Clin Oncol 24(21):3458–3464

Morita M, Kuwano H, Ohno S, Kitamura K, Sugimachi K (2000) Antiemetic effect of ramosetron during hyperthermo-chemo-radiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res 20:3631–3636

Okamoto S, Takahashi S, Tanosaki R et al (1996) Granisetron in the prevention of vomiting induced by conditioning for stem cell transplantation: a prospective randomized study. Bone Marrow Transplant 17:679–683

Prentice HG, Cunningham S, Ganhi L, Cunningham J, Collis C, Hamon MD (1995) Granisetron in the prevention of irradiation-induced emesis. Bone Marrow Transplant 15:445–448

Aass N, Hatun D, Thoresen M, Fossa SD (1997) Prophylactic use of tropisetron or metoclopramide during adjuvant abdominal radiotherapy of seminoma stage I: a randomised, open trial in 23 patients. Radiother Oncol 45(2):125–128

Abbott B, Ippoliti C, Bruton J, Neumann J, Whaley R, Champlin R (1999) Antiemetic efficacy of Granisetron plus dexamethasone in bone marrow transplant patients receiving chemotherapy and total body irradiation. Bone Marrow Transplant 23:265–269

Gibbs SJ, Cassoni AM (1996) A pilot study to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of Ondansetron and Granisetron in fractionated total body irradiation. Clin Oncol 8:182–184

Sorbe B, Berglind AM (1992) Tropisetron, a new 5-HT3-receptor antagonist, in the prevention of radiation-induced nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Drugs 43(Suppl 3):33–39

Aapro M, Blower P (2005) 5-Hydroxytryptamine type-3 receptor antagonists for chemotherapy-induced and radiotherapy-induced nausea and emesis: can we safely reduce the dose of administered agents? Cancer 104(1):1–18

Salvo N, Doble B, Khan L, et al. (2012) Prophylaxis of radiation-induced nausea and vomiting using 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 serotonin receptor antagonists: a systematic review of randomized trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82:408

Blower PR (2003) Granisetron: relating pharmacology to clinical efficacy. Support Care Cancer 11:93–100

Acknowledgments

Kristopher Dennis is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship Award. We thank Mr. Henry Lam from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Library for performing the database searches.

Disclosures

Speaker fees (KD,CD), consultancy (CD), and research funding (CD,EC) from Merck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dennis, K., Makhani, L., Maranzano, E. et al. Timing and duration of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist therapy for the prophylaxis of radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized studies. J Radiat Oncol 2, 271–284 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13566-012-0030-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13566-012-0030-2