Abstract

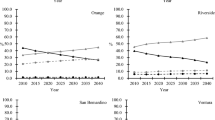

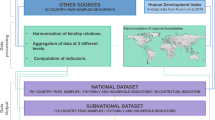

This article presents the core methodological ideas and empirical assessments of an extended cohort-component approach (known as the “ProFamy model”), and applications to simultaneously project household composition, living arrangements, and population sizes–gender structures at the subnational level in the United States. Comparisons of projections from 1990 to 2000 using this approach with census counts in 2000 for each of the 50 states and Washington, DC show that 68.0 %, 17.0 %, 11.2 %, and 3.8 % of the absolute percentage errors are <3.0 %, 3.0 % to 4.99 %, 5.0 % to 9.99 %, and ≥10.0 %, respectively. Another analysis compares average forecast errors between the extended cohort-component approach and the still widely used classic headship-rate method, by projecting number-of-bedrooms–specific housing demands from 1990 to 2000 and then comparing those projections with census counts in 2000 for each of the 50 states and Washington, DC. The results demonstrate that, compared with the extended cohort-component approach, the headship-rate method produces substantially more serious forecast errors because it cannot project households by size while the extended cohort-component approach projects detailed household sizes. We also present illustrative household and living arrangement projections for the five decades from 2000 to 2050, with medium-, small-, and large-family scenarios for each of the 50 states; Washington, DC; six counties of southern California; and the Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area. Among many interesting numerical outcomes of household and living arrangement projections with medium, low, and high bounds, the aging of American households over the next few decades across all states/areas is particularly striking. Finally, the limitations of the present study and potential future lines of research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, changes in headship rates may depend on whether the census or survey was carried out in the daytime or evening and whether more women or men were available to complete the questionnaire.

The “subnational level” referred in this article does not include small counties/cities/towns and other kinds of small areas (possibly even tracts or block groups) that do not have reasonably reliable data from which to estimate the demographic summary parameters.

A married or cohabiting man cannot be a reference person because we already chose the married or cohabiting woman as the reference person, and one household cannot have two reference persons.

The seven marital/union statuses are (1) never-married and not cohabiting, (2) married, (3) widowed and not cohabiting, (4) divorced and not cohabiting, (5) never-married and cohabiting, (6) widowed and cohabiting, and (7) divorced and cohabiting.

Because number of coresiding children is equal to or less than parity, the number of composite statuses of parity and coresiding children is

rather than (6 × 6).

rather than (6 × 6).Ideally, one may wish to differentiate the marital-/union-status transition probabilities by parity and coresidence status with children. Such differentiation is, however, not practically feasible because it would require a data set with a very large sample size (not available to us currently but not theoretically impossible at some future time point for some specific populations) for estimating the parity-/coresidence-/marital-status-/union-status–specific transition probabilities at each single age for men and women of each race group, with a reasonable accuracy.

With the model standard schedules in hand, analysts can concentrate on projecting future demographic summary parameters. This can be done by using conventional time series analysis by statistical software (e.g., SAS, SPSS, or STATA) or expert opinion approach. Time series data on other related socioeconomic covariates (e.g., average income, education, urbanization) also can be used in projecting the demographic summary parameters.

The numerical projections reported in this article were calculated with the ProFamy computer software program, which contains a demographic database of the U.S. age-specific schedules of demographic rates to assist users in making projections. The ProFamy software for household and living arrangements projections can be downloaded (http://www.profamy.com/).

National Survey of Family Households (NSFH) conducted in 1987–1988, 1992–1994, and 2002; National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) conducted in 1983, 1988, 1995, and 2002; Current Population Surveys (CPS) conducted in 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995; Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) conducted in 1996. (See Zeng et al. (2012) for discussions on justifications of pooling data from the four surveys.)

We compare six main indices of household projections and six main indices of population projections for each of the 50 states and Washington, DC, and thus both of the number of household indices and the total number of population indices under comparisons are 306.

We performed another set of the tests of projections from 2000 onward using ProFamy approach and data prior to 2001 and comparing the projections and the American Community Survey (ACS) observations in 2006 for each of the 50 states and Washington, DC. It turns out that 34.2 %, 35.0 %, 21.9 %, and 9.0 % of the percentage errors of the 306 indices of the household projections are <1.0 %, 1.0 % to 2.99 %, 3.0 % to 4.99 %, and 5.0 % to 9.99 %, respectively, and none is more than 10 %. A similar scale and pattern of forecast errors were also found in tests of projections from 2000 onward using ProFamy approach and data prior to 2001 and comparing the projected and ACS observations in 2006 and 2009 for the six SC counties and the M-S area (Wang 2009a,b, 2011a,b). We did not present detailed results from these additional tests here (they are available upon request), mainly because the 2006 and 2009 ACS data may not be accurate enough to serve as a benchmark standard for the validation tests (Alexander et al. 2010; Swanson 2010).

The zero-bedroom housing unit term means that the bedroom is mixed with the living room.

Our research indicates that the increase in proportion of American households with six or more persons in 2000 compared with 1990 is due to the changing racial composition of the population, given that Hispanic, Asian, and other nonwhite and nonblack minority groups have higher proportions of large households with six or more persons and are growing substantially faster.

One common approach in population projection is to hold some of the current demographic rates constant throughout the projection horizon (e.g., Day 1996; Treadway 1997). Smith et al. (2001:83–84) argued that neither the direction nor the magnitude of future changes can be predicted accurately, and thus if upward or downward movements are more or less equally likely, the constant demographic rates provide a reasonable forecast of future rates.

Low mortality may (1) reduce the U.S. average household size through increasing number of elderly households that are mostly small (one or two persons) and (2) increase the size of some households by increasing the survivorship of adults and children in these larger households. The effects of the latter may be smaller than those of the former because a further decrease in adult and child mortality in the United States is limited, but the prolongation of elderly life span may have larger effects.

The race-/sex-specific demographic parameters (TFR is parity-specific) (see parameters (a–h in Table 1, panel 3) in the medium-, small-, and large-family scenarios in selected years from 2000 to 2050 for each of the 50 states; Washington, DC; each SC county; and the M-S area can be listed in one large table. Including them in this article would require an unfeasibly large number of pages.

Zeng et al. (2010) preliminarily assessed the projection accuracy of the combined approach using the ratio method and the ProFamy approach by calculating projections from 1990 to 2000 and comparing projections with census-observed counts in 2000 for sets of randomly selected 25 counties and 25 cities that are more or less evenly distributed across the United States. The comparisons show that most forecast errors are reasonably small, at less than 5 %.

References

Alexander, J. T., Davern, M., & Stevenson, B. (2010, April). Inaccurate age and sex data in the census PUMS file. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Dallas, TX.

Bell, M., & Cooper, J. (1990, November). Household forecasting: Replacing the headship rate model. Paper presented at the Fifth National Conference, Australian Population Association, Melbourne.

Bongaarts, J. (1987). The projection of family composition over the life course with family status life tables. In J. Bongaarts (Ed.), Family demography: Methods and applications (pp. 189–212). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Booth, H. (1984). Transforming Gompertz’s function for fertility analysis: The development of a standard for the relational Gompertz function. Population Studies, 38, 495–506.

Brass, W. (1974). Perspectives in population prediction: Illustrated by the statistics of England and Wales. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 137, 532–583. Series A.

Brass, W. (1978). The relational Gompertz model of fertility by age of women. Unpublished manuscript, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Brass, W. (1983). The formal demography of the family: An overview of the proximate determinates (Occasional Paper 31). London, UK: Office of Population census and Surveys.

Campbell, P. R. (2002). Evaluating forecast error in state population projections using Census 2000 counts (U.S. Census Bureau Population Division Working Paper Series No. 57). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0057/twps0057.html

Coale, A. J. (1984). Life table construction on the basis of two enumerations of a closed population. Population Index, 50, 193–213.

Coale, A. J. (1985). An extension and simplification of a new synthesis of age structure and growth. Asian and Pacific Forum, 12, 5–8.

Coale, A. J., Demeny, P., & Vaughn, B. (1983). Regional model life tables and stable populations. New York: Academic Press.

Coale, A., & Trussell, T. J. (1974). Model fertility schedules: Variations in the age structure of childbearing in human population. Population Index, 40, 185–258.

Crowley, F. D. (2004). Pikes Peak Area Council of Governments: Small area estimates and projections 2000 through 2030. Southern Colorado Economic Forum, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. Retrieved from http://www.ppacg.org/Trans/2030/Volume%20III/Appendix%20G%20-%20Small%20Area%20Forecasts.pdf

Dalton, M., O’Neill, B., Prskawetz, A., Jiang, L., & Pitkin, J. (2008). Population aging and future carbon emissions in the United States. Energy Economics, 30, 642–675.

Day, J. (1996). Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050 (Current Population Reports P25-1130). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

ESRI. (2007). Evaluating population projections—The importance of accurate forecasting (ESRI White Paper). Retrieved from http://www.esri.com/library/whitepapers/pdfs/evaluating-population.pdf

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics (FIFARS). (2004). Older Americans 2004: Key indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Feng, Q., Wang, Z., Gu, D., & Zeng, Y. (2011). Household vehicle consumption forecasts in the United States, 2000 to 2025. International Journal of Market Research, 53(5).

Freedman, V. A. (1996). Family structure and the risk of nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology, 51B(2), S61–S69.

Goldscheider, F. K. (1990). The aging of the gender revolution: What do we know and what do we need to know? Research on Aging, 12, 531–545.

Himes, C. L. (1992). Future caregivers: Projected family structures of older persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 47(1), S17–S26.

Hollmann, F. W., Mulder, T. J., & Kallan, J. E. (2000). Methodology and assumptions for the population projections of the United States: 1999 to 2100 (Population Division Working Paper No. 38). Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Ip, F., & McRae, D. (1999). Small area household projections—A parameterized approach. Population Section, Ministry of Finance and Corporate Relations, Province of British Columbia, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/data/pop/pop/methhhld.pdf

Keilman, N. (1988). Dynamic household models. In N. Keilman, A. Kuijsten, & A. Vossen (Eds.), Modelling household formation and dissolution (pp. 123–138). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Keilman, N. (2003). The threat of small households. Nature, 421, 489–490.

Khan, H. T. A., & Lutz, W. (2008). How well did past UN population projections anticipate demographic trends in six South-east Asian countries? Asian Population Studies, 4, 77–95.

Land, K. C., & Rogers, A. (1982). Multidimensional mathematical demography. New York: Academic Press.

Liu, J., Dally, C. C., Ehrlich, P. R., & Luck, G. W. (2003). Effects of household dynamics on resource consumption and biodiversity. Nature, 421, 530–533.

Lutz, W., & Prinz, C. (1994). The population module. In W. Lutz (Ed.), Population-development-environment: Understanding their interactions in Mauritius (pp. 221–231). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag Press.

Mackellar, F. L., Lutz, W., Prinz, C., & Goujon, A. (1995). Population, households, and CO2 emissions. Population and Development Review, 21, 849–866.

Mason, A., & Racelis, R. (1992). A comparison of four methods for projecting households. International Journal of Forecasting, 8, 509–527.

Moffitt, R. (2000). Demographic change and public assistance expenditures. In A. J. Auerbach & R. D. Lee (Eds.), Demographic change and public assistance expenditures (pp. 391–425). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, M. (1991). Modelling households: A synthesis. In M. J. Murphy & J. Hobcraft (Eds.), Population research in Britain, A supplement to population studies (Vol. 45, pp. 151–176). London, UK: Population Investigation Committee, London School of Economics.

Murray, C. J. L., Ferguson, B. D., Lopez, A. D., Guillot, M., Salomon, J. A., & Ahmad, O. (2003). Modified logit life table system: Principles, empirical validation, and application. Population Studies, 57, 165–182.

Myers, D., Pitkin, J., & Park, J. (2002). Estimation of housing needs amid population growth and change. Housing Policy Debate, 13, 567–596.

Paget, W. J., & Timaeus, I. M. (1994). A relational Gompertz model of male fertility: Development and assessment. Population Studies, 48, 333–340.

Prskawetz, A., Jiang, L., & O’Neill, B. (2004). Demographic composition and projections of car use in Austria. In Vienna yearbook of population research (pp. 274–326). Vienna, Austria: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

Rao, J. N. K. (2003). Small area estimation. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Rogers, A. (1975). Introduction to multi-regional mathematical demography. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Rogers, A. (1986). Parameterized multistate population dynamics and projections. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81, 48–61.

Rogers, A. (1995). Multiregional mathematical demography: Principles, methods, and extensions. New York: Wiley.

Schoen, R. (1988). Modeling multi-group populations. New York: Plenum Press.

Schoen, R., & Standish, N. (2001). The retrenchment of marriage: Results from marital status life tables for the United States, 1995. Population and Development Review, 27, 553–563.

Smith, S. K. (2003). Small area analysis. In P. Demeny & G. McNicoll (Eds.), Encyclopedia of population (pp. 898–901). Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference.

Smith, S. K., & Morrison, P. A. (2005). Small area and business demography. In D. L. Poston & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population (pp. 761–786). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Smith, S. K., Rayer, S., & Smith, E. A. (2008). Aging and disability: Implications for the housing industry and housing policy in the United States. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74, 289–306.

Smith, S. K., Rayer, S., Smith, E., Wang, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2012). Population aging, disability and housing accessibility: Implications for sub-national areas in the United States. Housing Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/02673037.2012.649468

Smith, S. K., Tayman, J., & Swanson, D. A. (2001). State and local population projections: Methodology and analysis. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Soldo, J., Wolf, D. A., & Agree, E. M. (1990). Family, households, and care arrangements of frail older women: A structural analysis. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 45, S238–S249.

Spicer, K., Diamond, I., & Ni Bhrolchain, M. (1992). Into the twenty-first century with British households. International Journal of Forecasting, 8, 529–539.

Stupp, P. W. (1988). A general procedure for estimating intercensal age schedules. Population Index, 54, 209–234.

Swanson, D. A. (2010, April). The methods and materials used to generate two key elements of the housing unit method of population estimation: Vacancy rates and persons per household. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Dallas, TX.

Swanson, D. A., & Pol, L. G. (2009). In Y. Zeng (Ed.), Demography, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) (www.eolss.net), coordinated by the UNESCO-EOLSS Committee. Oxford, UK: EOLSS Publishers Co. Ltd.

Treadway, R. (1997). Population projections for the state and counties of Illinois. Springfield: State of Illinois.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2008). Interim projections of the U.S. population by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: Summary methodology and assumptions. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/idbsummeth.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (1996). Projections of the number of households and families in the United States: 1995 to 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration (Current Population Reports P25-1129). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

United Nations. (1982). Model life tables for developing countries (ST/SEA/SER, A/77, Sales No. E. 81, XIII, 7). New York: United Nations.

Van Imhoff, E., & Keilman, N. (1992). LIPRO 2.0: An application of a dynamic demographic projection model to household structure in the Netherlands. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Swets & Zeithinger.

Van Imhoff, E., Kuijsten, A., Hooimeiger, P., & van Wissen, L. (1995). Epilogue. In E. Imhoff, A. Kuijsten, P. Hooimeiger, & L. van Wissen (Eds.), Household demography and household modeling (pp. 345–351). New York: Plenum.

Wang, Z. (2009a). Households and living arrangements forecasting and the associated database development for southern California six counties and the whole region, 2000–2040. (in response to RFP No. 09-043-IN of SCAG: Household Projection Model Development: Simulation Approach) (Technical Report No. 09–02). Chapel Hill, NC: Households and Consumption Forecasting Inc.

Wang, Z. (2009b). Household projection and living arrangements projections for Minneapolis-St. Paul Region, 2000–2050 (Technical report No. 09–03). Chapel Hill, NC: Households and Consumption Forecasting Inc.

Wang, Z. (2011a). The 2011 updating of households and living arrangements forecasting for Southern California six counties and the whole region, 2000–2040 (Technical report No. 11–01). Chapel Hill, NC: Households and Consumption Forecasting Inc.

Wang, Z. (2011b). The 2011 updating of household projection and living arrangements projections for Minneapolis-St. Paul region, 2000–2050 (Technical report No. 11–02). Chapel Hill, NC: Households and Consumption Forecasting Inc.

Willekens, F.J., I. Shah, J.M. Shah, and P. Ramachandran. (1982). Multistate analysis of marital status life tables: theory and application. Population Studies, 36, 129–144.

Zeng, Y. (1986). Changes in family structure in China: A simulation study. Population and Development Review, 12, 675–703.

Zeng, Y. (1988). Changing demographic characteristics and the family status of Chinese women. Population Studies, 42, 183–203.

Zeng, Y. (1991). Family dynamics in China: A life table analysis. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Zeng, Y., Coale, A., Choe, M. K., Liang, Z., & Liu, L. (1994). Leaving parental home: Census based estimates for China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, France, and Sweden. Population Studies, 48, 65–80.

Zeng, Y., Land, K. C., Wang, Z., & Gu, D. (2006). U.S. family household momentum and dynamics—Extension and application of the ProFamy method. Population Research and Policy Review, 25, 1–41.

Zeng, Y., Land, K. C., Wang, Z., & Gu, D. (2010, April). Extended cohort-component approach for households projection at sub-national levels—With empirical validations and applications of households forecasts for 50 states and DC. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Dallas, TX.

Zeng, Y., Morgan, S. P., Wang, Z., Gu, D., & Yang, C. (2012). A multistate life table analysis on union regimes in the United States—Trends and racial differentials, 1970–2002. Population Research and Policy Review, 31, 207–234.

Zeng, Y., Vaupel, J. W., & Wang, Z. (1997). A multidimensional model for projecting family households—With an illustrative numerical application. Mathematical Population Studies, 6, 187–216.

Zeng, Y., Vaupel, J. W., & Wang, Z. (1998). Household projection using conventional demographic data. Population and Development Review, Supplementary Issue: Frontiers of Population Forecasting, 24, 59–87.

Zeng, Y., Wang, Z., Jiang, L., & Gu, D. (2008). Future trend of family households and elderly living arrangement in China. GENUS—An International Journal of Demography, LXIV(1–2), 9–36.

Zeng, Y., Wang, Z., Ma, Z., & Chen, C. (2000). A simple method for estimating α and β: An extension of Brass relational Gompertz fertility model. Population Research and Policy Review, 19, 525–549.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was mainly supported by NIA/NIH SBIR Phase I and Phase II project grants. We also thank the Population Division of U.S. Census Bureau, NICHD (grant 5 R01 HD41042-03), NIA (grant 1R03AG18647-1A1) and NSFC international collaboration project (grant 71110107025), Duke University, Peking University, and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research for supporting related basic and applied research. We thank Huashuai Chen for preparing the graphics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Land, K.C., Wang, Z. et al. Household and Living Arrangement Projections at the Subnational Level: An Extended Cohort-Component Approach. Demography 50, 827–852 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0171-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0171-3

rather than (6 × 6).

rather than (6 × 6).