Abstract

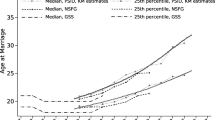

We estimate trends and racial differentials in marriage, cohabitation, union formation and dissolution (union regimes) for the period 1970–2002 in the United States. These estimates are based on an innovative application of multistate life table analysis to pooled survey data. Our analysis demonstrates (1) a dramatic increase in the lifetime proportions of transitions from never-married, divorced or widowed to cohabiting; (2) a substantial decrease in the stability of cohabiting unions; (3) a dramatic increase in mean ages at cohabiting after divorce and widowhood; (4) a substantial decrease in direct transition from never-married to married; (5) a significant decrease in the overall lifetime proportion of ever marrying and re-marrying in the 1970s to 1980s but a relatively stable pattern in the 1990s to 2000–2002; and (6) a substantial decrease in the lifetime proportion of transition from cohabiting to marriage. We also present, for the first time, comparable evidence on differentials in union regimes between four racial groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The disaggregation approach, developed by Erikson et al. (1993), pools large numbers of national surveys and then disaggregates the data so as to calculate opinion percentages by state (Lax and Phillips (2009, p. 107). For example, the original datasets of over 100 surveys on gay rights issues were pooled to estimate public opinions about support for same-sex marriage at the state level (Lax and Phillips 2009). Fancy (1997) pooled data from surveys with data on bird densities in different areas and this approach was validated in two field studies where the density of birds could be determined by independent methods.

For example, persons who had more than three marriages constituted 0.67% of all applicable interviewees in SIPP96.

By applying the original sampling weights, we have total risk population and events at different time points and thus we can estimate unbiased race-age-specific marital/union status transition rates.

We did not include interaction terms in the event history analysis models because almost all interactions are not statistically significant, and in the few cases where the interactions are significant, the main effects are unstable and uninterpretable. We believe that employing the method of event history analysis provides the best estimates of race-sex-age-specific o/e rates for different periods.

The assumption of ignoring the duration-specific effects may be released by employing the semi-Markov models which introduce duration-specific (in addition to age-specific) rates (e.g., Rajulton 2001).

Hereafter, the note in the parenthesis “rows # in Table * (# and * are alphabetical numbers) refers to the two rows numbered # in the “Women” and “Men” panels in the Table labeled as *.

The measurements presented in this subsection concerning the timing of cohabitation before first marriage, after divorce, and after widowhood are estimated directly using the cohabitation history data from NSFH and NSFG.

Another possible explanation is that people in the 1970s were more likely to be widowed at younger ages due to acute diseases and accidents (or even the Vietnam war).

Both the Hispanics and Asians/Others categories are quite heterogeneous. The largest group of Hispanics is Mexican, but there are substantial numbers from Cuba, Puerto Rico and elsewhere in Central and South America. “Asians/Others” are mostly Asian (itself a heterogeneous category) but also includes small numbers of Pacific Islanders and American Indians. However, if we further distinguished more detailed categories within the Hispanic and Asian/Other race/ethnic groups, the sub-sample size in the survey datasets would be too small and would result in serious biases in the race-sex-age-specific o/e rates estimations and the multistate life table construction. Thus, we only offer a four-category race/ethnic variable that has mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories and provides a sense of racial/ethnic variations in U.S. union regimes, which is the best we can do given the available survey data sources.

References

Allison, P. D. (1995). Survival analysis using the SAS system: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Anstey, K., Byles, J. E., Luszcz, M. A., Mitchell, P., Steel, D., Booth, H., et al. (2010). Cohort profile: The dynamic analyses to optimize ageing (DYNOPTA) Project. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 44–51.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brace, P., Sims-Butler, K., Arceneaux, K., & Johnson, M. (2002). Public opinion in the American states: New perspectives using national survey data. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 173–189.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce and remarriage in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics, 23(22), 1–93.

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabiters: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 833–846.

Bumpass, L. L., & Lu, H.-H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41.

Bumpass, L. L., & Sweet, J. A. (1990). Changing patterns of remarriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52, 747–756.

Bumpass, L. L., & Sweet, J. A. (1995). Cohabitation, marriage, and non-marital childbearing and union stability: Preliminary findings from NSFH2. NSFH working paper no 65. Madison: University of Wisconsin, Center for Demography and Ecology.

Casper, L. M., & Cohen, P. N. (2000). How does POSSLQ measure up? Historical estimates of cohabitation. Demography, 37(2), 237–245.

Cherlin, A. J. (1992). Marriage, divorce, remarriage. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cherlin, A. J. (1999). Going to extremes: Family structure, children’s well-being, and social science. Demography, 36, 421–428.

DeMaris, A., & MacDonald, W. (1993). Premarital cohabitation and marital instability: A test of the unconventionality hypothesis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55(2), 399–407.

Elizabeth, A. (2004). “United States life tables, 2002.” National vital statistics reports (Vol. 53, no 6). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics

Fancy, S. G. (1997). A new approach for analyzing bird densities from variable circular-plot counts. Pacific Science, 51(1), 107–114.

Goldstein, J. R. (1999). The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36, 409–414.

Goldstein, J. R., & Kenney, C. T. (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–519.

Hayford, S., & Morgan, S. P. (2008). The quality of retrospective data on cohabitation. Demography, 45(1), 129–141.

Kposowa, A. J. (1998). The impact of race on divorce in the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29, 529–548.

Land, K. C., & Rogers, A. (Eds.). (1982). Multidimensional mathematical demography. New York: Academic Press.

Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2009). How should we estimate public opinion in the states? American Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 107–121.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (1995). Why marry? Race and the transition to marriage among cohabitors. Demography, 32(4), 509–520.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2000). Serial parenting and economic support for children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 111–122.

Minicuci, N., Noale, M., Bardage, C., et al. (2003). Cross-national determinants of quality of life from six longitudinal studies on aging: The CLESA project. Aging and Clinical Experimental Research, 15, 187–202.

Morgan, P. P., Botev, K., Chen, R., & Huang, J. (1999). White and Non-white trends in first birth timing: Comparisons using vital registration and current population surveys. Population Research and Policy Review, 18, 339–356.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review, 20, 293–342.

Phillips, A. J., & Sweeney, M. M. (2005). Premarital cohabitation and marital disruption among White, Black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 296–314.

Preston, S. H., Heuveline, P., & Guillot, M. (2001). Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

Rajulton, F. (2001). Analysis of life histories: A state-space approach. Special Issue of Longitudinal Methodology-Canadian Studies in Population, 28(2), 341–359. (Presenting the LIFEHIST, a computer program to analyze life histories through a state-space approach).

Raley, R. K. (2000). Recent trends and differentials in marriage and cohabitation: The United States. In W. Linda, et al. (Eds.), The ties that binds (pp. 19–39). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Rogers, A. (1975). Introduction to multi-regional mathematical demography. New York: Wiley.

Schenker, N., & Raghunathan, T. E. (2007). Combining information from multiple surveys to enhance estimation of measures of health. Statistics in Medicine, 26, 1802–1811.

Schoen, R. (1987). The continuing retreat from marriage: Figures from 1983 U.S. Marital status life tables. Sociology and Social Research, 71, 108–109.

Schoen, R. (1988). Modeling multigroup population. New York: Plenum Press.

Schoen, R., & Canudas-Romo, V. (2006). Timing effects on divorce: 20th Century experience in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(3), 749–758.

Schoen, R., & Cheng, Y.-H. A. (2006). Partner choice and the differential retreat from marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1), 1–10.

Schoen, R., Landale, N., & Daniels, K. (2007). Family transitions in young adulthood. Demography, 44(4), 807–820.

Schoen, R., & Standish, N. (2001). The retrenchment of marriage: Results from marital status life tables for the United States, 1995. Population and Development Review, 27(3), 553–563.

Schoen, R., & Weinick, R. M. (1993). The slowing metabolism of marriage: Figures from 1988 U.S. marital status life tables. Demography, 30, 737–746.

Sherif-Trask, B., & Koivunen, J. M. (2007). Trends in marriage and cohabitation. In B. Sherif Trask & R. Hamon (Eds.), Cultural diversity and families: Expanding perspectives (pp. 80–99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Simmons, T., & O’Connell, M. (2003). Married-couple and unmarried-partner households: 2000. Census 2000 special reports, Census Bureau.

Smock, P. J. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: Changes and their driving forces. NBER Working Paper No. 12944, Issued in March 2007.

Strow, C. W., & Strow, B. K. (2006). A history of divorce and remarriage in the United States. Humanomics, 22(4), 239–257.

Teitler, J. O., Reichman, N. E., & Koball, H. (2006). Contemporaneous versus retrospective reports of cohabitation in the fragile families survey. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 469–477.

Thornton, Arland. (1988). Cohabitation and marriage in the 80 s. Demography, 25, 497–508.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., Xie. Y. (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank and UN Population Division. (2007). Levels and trends of child mortality in 2006: Estimates developed by the inter-agency group for child mortality estimation, New York, United Nations.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2001). U.S. adults postponing marriage. Census bureau reports. Accessed March 20, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2001/cb01-113.html.

White, L., & Rogers, S. J. (2000). Economic circumstances and family outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1035–1051.

Willekens, F. J., Shah, I., Shah, J. M., & Ramachandran, P. (1982). Multistate analysis of marital status life table: Theory and application. Population Studies, 36(1), 129–144.

Wooldridge, J. (2003). Introductory econometrics—A modern approach. Mason: Thomson South-Western Press.

Wu, Z., & Balakrishnan, T. R. (1995). Dissolution of premarital cohabitation in Canada. Demography, 32, 521–532.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by NICHD grant R01 HD 41042 (PI: S. Philip Morgan); NIA grant R03 AG 18647 (PI: Yi Zeng), and a grant from the Census Bureau (PI: Yi Zeng). Development of the ProFamy software used for constructing the multistate life tables and the input database for this article has been supported by NIA/NIH SBIR grant 5R44AG022734-03 (PI: Zhenglian Wang). We are very grateful for the institutional support provided by the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, the Department of Sociology at Duke University and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. All of the raw data used in this study were downloaded from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) web site. We greatly appreciate comments/suggestions from Steven Ruggles and Robert Schoen. Robert Schoen also provided all-race combined age-sex-specific marriage/divorce rates and age-sex-marital status specific death rates based on vital statistics. Assistance in data preparation was provided by Gary Thomson and Qiang Li.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Definitions of the summary measures of the multistate union regimes life table

For the sake of clarity, we omit dimensions of race, sex and period in all variables, but we should keep in mind that all estimates are race-sex-period-specific in this study.

Lifetime proportions of marriage/union formation and dissolution

Let m ij (x) denote the age-specific o/e rate of transition from marital/union status i to j; the codes of i, j represent: 1. never-married & not-cohabiting, 2. currently married, 3. widowed and not-cohabiting, 4. divorced and not cohabiting, 5. never-married and cohabiting, 6. widowed and cohabiting, 7. divorced and cohabiting; L i (x), person-years lived in marital/union status i between age x and x + 1 in the life table population; α and ω, the lowest and highest age considered in constructing the multistate life tables. In our current application, we consider that α = 15 and ω = 99.

Let SC denote the lifetime proportion of transition from never-married to cohabitation.

Let WC denote the lifetime proportion of transition from widowed to cohabitation.

Let DC denote the lifetime proportion of transition from divorced to cohabitation.

Note that SC, WC, and DC cannot be interpreted as proportion of ever experiencing cohabitation before first marriage and after divorce or widowhood, because the numerators of SC, WC, and DC include the events of second and higher order of cohabitation before first marriage or after divorce or widowhood. In other words, SC, WC, and DC include multiple events for some people of entering cohabitation union and entering the risk populations of never-married, widowed and divorced.

Let CM denote the overall lifetime proportion of transition from cohabiting to marrying.

Let CS denote the lifetime proportion of cohabitation union dissolution.

Let SM denote the overall lifetime proportion of first marriage regardless of cohabiting status before first marriage. SncM denote the proportion of first marriage while not-cohabiting before marrying among all first marriages; ScM, the proportion of first marriage while cohabiting before marrying among all first marriages;

Let MD denote the lifetime proportion of divorce.

Let WM denote overall lifetime proportion of remarriage among those who are widowed regardless of cohabiting status before remarriage; WncM, the proportion of remarriage while not-cohabiting before remarrying among all remarriages of widowed; WcM, the proportion of remarriage while cohabiting before remarrying among all remarriages of widowed.

Let DM denote overall lifetime proportion of remarriage among those who are divorced regardless of cohabiting status before remarriage; DncM, the proportion of remarriage while not-cohabiting before remarrying among all remarriages of divorcees; DcM, the proportion of remarriage while cohabiting before remarrying among all remarriages of divorcees.

Average life-time numbers of cohabitations, marriages, divorces, and widowhoods per person

AC—the average number of cohabitation unions per person in the lifetime;

AM—the average number of marriages (including the first marriage and remarriages) per person in the lifetime;

AD—the average number of divorces per person in the lifetime;

The proportion of life span after age \( \partial \) (the lowest marriageable or cohabiting age) spent in different marital/union statuses

Let P i denote the proportion of life span after age \( \partial \) spent in marital/union status i.

Appendix 2: A procedure to adjust the o/e rates of marital/cohabiting union status transitions based on the NSFH and NSFG data for consistency with the o/e rates of marital status transitions based on the CPS, SIPP, NSFH, and NSFG data

We perform the adjustments for each of the race groups, men, women, and the periods (1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000–2002), respectively, while we omit the dimension indices of race, sex and period in the formulas for simplicity of the presentation.

Let m4ij(x) denote the o/e rate of transition from marital status i to marital status j between age x and x + 1 based on the CPS, SIPP, NSFH, and NSFG data, using a classic 4 marital statuses model (i,j = 1,2,3,4, represent never-married, married, widowed and divorced, respectively, excluding cohabitation).

m*ij(x), observed and unadjusted age-specific o/e rates of transitions from marital/union status i to j (i,j = 1,2,3,4,5,6,7, including cohabitation, see the definitions in Appendix 1), based on NSFH and NSFG data;

mij(x), the final adjusted age-specific o/e rates of transitions from marital/union status i to j (i,j = 1,2,3,4,5,6,7, including cohabitation) based on pooled survey data, and adjusted to be consistent with m4ij(x); mij(x) can be analytically transferred into Pij(x), age-specific probabilities of transitions from marital/union status i to j using the standard formula in multistate demography (see, e.g., Willekens et al. 1982; Schoen 1988; Preston et al. 2001).

The goal of the adjustment is to make the average number of marriages including first and re-marriages (AM7) and average number of divorces (AD7) in the life time in the 7 marital/union status life table (including cohabitation) based on NSFH and NSFG data equal to the corresponding average numbers (AM4 and AD4) in the life table of 4 marital statuses excluding cohabitation based on all of the data from CPS, SIPP, NSFH, and NSFG.

We use the m4ij(x) to compute P4ij(x), age-specific probabilities of marital status transitions based on CPS, SIPP, NSFH, and NSFG data, using the standard formula. Based on P4ij(x), we construct a multi-state life table to get L4i(x), using formulas (1) and (2) presented above. We then use m4ij(x) and L4i(x) to compute the AM4 and AD4 in the 4 marital statuses model based on CPS, SIPP, NSFH, and NSFG data.

We then employ the following two-step procedure to adjust the observed o/e rates of 1st marriage, divorce, and remarriages (m*12(x), m*52(x), m*24(x), m*32(x), m*62(x), m*42(x), and m*72(x)), but do not need to adjust the observed o/e rates of cohabitation union formation and dissolution (m*15(x), m*36(x), m*47(x), m*51(x), m*63(x), m*74(x)) based on NSFH and NSFG.

Step 1: Adjustment for the o/e rates of first marriage, remarriage, and divorce

We use the unadjusted survey-based m*ij(x) to compute P*ij(x), and we then use P*ij(x) to construct an initial multi-state life table and get the initial L*i(x) using formulas (1) and (2); we then use m*ij(x) and L*i(x) to compute the initial AM7* and AD7* in the 7 marital/union statuses model based on the NSFH and NSFG data.

We use AM4/AM7*, AD4/AD7* as adjustment factors (not age-specific) to adjust the corresponding age-specific o/e rates of first marriage, remarriage, and divorce for not-cohabiting and cohabiting persons at ages x (x = α to ω).

Step 2: Check whether the goal of the adjustment is achieved

We use the first adjusted m’ij(x) to compute the first adjusted P′ij(x), and use m′ij(x) to replace m*ij(x) in the formulas (3) and (4) to get the first adjusted AM7′ and AD7′. If the absolute values of the relative difference between AM7′ and AM4 and between AD7′ and AD4 are all less than a selected criterion (e.g., 0.5%), we have completed Step 2 and have the final estimates of the o/e rates (mij(x)). Otherwise, we will have to use the first adjusted AM7′ and AD7′ to replace AM7* and AD7* in formulas (5–11) to repeat the iterative procedures described in Step 1 and Step 2 until the selected criterion is achieved.

Appendix 3

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Morgan, S.P., Wang, Z. et al. A Multistate Life Table Analysis of Union Regimes in the United States: Trends and Racial Differentials, 1970–2002. Popul Res Policy Rev 31, 207–234 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-011-9217-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-011-9217-2