Abstract

The phosphanegold(I) thiocarbamides, Ph3PAu{SC(OR)=NC6H4Me-4} for R = Me (1), Et (2) and iPr (3), have been shown to have essentially linear gold atom coordination geometries defined by phosphane-P and thiolate-S atoms, and exhibit minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values in the range of 1–37 μg/ml against four Gram-positive bacteria, namely Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus; compounds 1–3 are less potent against a broad panel of 16 Gram-negative bacteria. As the minimum bactericidal concentration values were quite similar to the MIC values, compounds 1–3 are effective bactericidal agents. The specific action against the four Gram-positive bacteria suggests they function by inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is now widely recognised that the increase in bacterial resistance, the rapid emergence of new infections, and even overprescription of antibiotics have significantly decreased the efficacy of drugs employed in the treatment of pathologies instigated by certain microorganisms [1, 2]. Infections caused by Gram-positive organisms are of major concern due to the increased incidence and the high level of multidrug resistance [3, 4]. Increasing resistance in both enterococci (lactic acid bacteria) and staphylococci (skin-colonising bacteria) [5] has accelerated the need for the development of new antimicrobial agents to treat these Gram-positive infections [6]. Herein, the specific antimicrobial activity against four Gram-positive bacteria exhibited by a series of gold compounds is described.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs based on gold are well established in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [7, 8]. Gold(I) compounds used in this context range from charged, polymeric and water-soluble gold(I) thiolates such as sodium gold(I) thiomalate (Myocrisin®) and the neutral, monomeric and lipophilic phosphanegold(I) thiolate, triethylphosphanegold(I) tetraacetylthioglucose (Auranofin®) [9, 10]. While research continues in developing new antirheumatic agents and in understanding the mechanism of action [11–14], much recent attention has focussed upon investigating the anticancer potential of gold(I) and, especially, gold(III) compounds [15–24]. Other ailments/diseases, too, have been investigated such as anti-viral (HIV AIDS), anti-asthma (acute corticosteroid) and even tropical diseases, e.g. malaria and Chagas disease [13, 14]. Attention has also been directed towards antimicrobial activity, the focus of the present report.

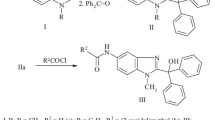

A range of synthetic gold compounds shown strong inhibitory and antimicrobial effects. Exploiting the anti-inflammatory activity of Auranofin® as well as its ability to inhibit thiol-based redox enzymes renders this an exciting prospect for the development of novel antimicrobial agents [24]. The majority of research in this area has in fact focussed upon analogues of Auranofin®, i.e. phosphanegold(I) thiolates [24–27], but with attention also being directed to the study of N-heterocyclic carbene [28], thiolate [29] and carboxylate [30, 31] derivatives. Relatively less consideration has been devoted to gold(III) species [32]. In the present study, phosphanegold(I) thiolates 1–3 (Fig. 1) will be shown to display marked biological activities. Specifically, 1–3 exhibit selective and antimicrobial activities against four Gram-positive bacteria suggesting that these may be potentially developed as alternative bactericidal agents.

Experimental

General

1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz NMR spectrometer with chemical shifts relative to tetramethylsilane as internal reference. 31P{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution on the same instrument but with the chemical shifts recorded relative to 85 % aqueous H3PO4 as external reference; abbreviations for NMR assignments: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; sept, septet; and m, multiplet. IR spectra were obtained as KBr pellets on a Perkin Elmer RX1 FTIR spectrophotometer. Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin Elmer PE 2400 CHN Elemental Analyser. Melting points were determined on a Krüss KSP1N melting point meter.

All chemicals and solvents were sourced commercially and used as received. All reactions were carried out under ambient conditions. The thiocarbamides, ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 for R = Me, Et and iPr, were prepared in quantitative yields as described in the literature [33]. For example, MeOC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 was prepared from the stoichiometric reaction of S=C=NC6H4Me-4 and MeOH in the presence of equimolar NaOH with MeOH serving as the solvent.

The phosphanegold(I) thiocarbamides, Ph3PAu{SC(OR)=NC6H4Me-4} for R = Me, Et and iPr, were obtained from the reaction of Ph3PAuCl precursor (synthesised by the reduction of KAuCl4 by sodium sulfite followed by addition of the stoichiometric amount of triphenylphosphane) with one mole equivalent of ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 in the presence of NaOH, following standard procedures [34]. Details for the synthesis of 3 are given here; 1 and 2 were prepared in an analogous fashion. NaOH (0.5 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was added to a suspension of Ph3PAuCl (0.5 mmol) in MeOH (20 mL), followed by addition of iPrOC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 in MeOH (20 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred for 3 h at 50 °C. An equivolume of dichloromethane was added and the solution was left for slow evaporation at room temperature, yielding colourless crystals after 2 weeks.

Characterisation

MeOC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 8.70 (br s, 1H, NH), 7.13 (br s, 4H, aryl-H), 4.11 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.32 (s, 3H, aryl-CH3) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 189.6 (Cq), 135.5 (C1), 134.4 (C4), 129.6 (C3), 122.0 (C2), 58.8 (OCH3), 21.0 (C5) ppm. Anal. Calc. for C8H9NOS: C, 59.64; H, 6.17; N, 7.73 %. Found: C, 59.26; H, 6.29; N, 7.74 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimeter): 3,234(br) ν(N–H), 1,451(s) ν(C–N), 1,204(s) ν(C=S), 1,061(s) ν(C–O). M.pt: 78–80 °C.

EtOC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 8.68 (br s, 1H, NH), 7.13 (br s, br, 4H, aryl-H), 4.62 (s, br, 2H, OCH2), 2.32 (s, 3H, aryl-CH3), 1.39 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.10 Hz) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 188.6 (Cq), 135.2 (C1), 134.6 (C4), 129.6 (C3), 121.6 (C2), 68.7 (OCH2), 21.0 (C5), 14.1 (CH3) ppm. Anal. Calc. for C9H11NOS: C, 61.50; H, 6.71; N, 7.17 %. Found: C, 61.30; H, 6.82; N, 7.23 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimter): 3,236(br) ν(N–H), 1,450(s) ν(C–N), 1,202(s) ν(C=S), 1,042(s) ν(C–O). M.pt: 64–67 °C.

iPrOC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 8.65 (br s, 1H, NH), 7.13 (br s, 4H, aryl-H), 5.65 (sept, 1H, OCH, J = 6.22 Hz), 2.32 (s, 3H, aryl-CH3), 1.39 (d, 6H, CH3, J = 6.20 Hz) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 187.7 (Cq), 135.0 (C1), 134.7 (C4), 129.5 (C3), 121.5 (C2), 73.7 (OCH), 21.7 (CH3), 20.9 (C5) ppm. Anal. Calc. for C10H13NOS: C, 63.12; H, 7.22; N, 6.69 %. Found: C, 63.35; H, 7.33; N, 6.70 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimeter): 3,221(br) ν(N–H), 1,462(s) ν(C–N), 1,205(s) ν(C=S), 1,087(s) ν(C–O). M.pt: 91–92 °C.

Ph3PAu{SC(OMe)=NC6H4Me-4} (1)

Yield: 0.297 g (93 %) colourless crystals from the slow evaporation from a dichloromethane/methanol mixture (1:1 v/v). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 7.53–7.40 (m, br, 15H, Ph3P), 6.82 (d, 2H, o-aryl-H, J CP = 8.04 Hz), 6.73 (d, 2H, m-aryl-H, J CP = 8.20 Hz), 3.90 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.03 (s, 3H, aryl-Me) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 164.4 (Cq), 148.6 (Ph, C1), 134.3 (d, o-PC6H5, J CP = 55.3 Hz), 131.6 (d, p-PC6H5, J CP = 8.8 Hz), 131.5 (Ph, C4), 129.6 (Ph, C3), 129.5 (d, i-PC6H5, J CP = 226.9 Hz), 129.1 (d, m-PC6H5, J CP = 45.8 Hz), 121.8 (Ph, C2), 55.3 (OCH3), 20.8 (aryl-Me) ppm. 31P{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 38.0 ppm. Anal. Calc. for C26H23AuNOPS: C, 50.71; H, 3.94; N, 2.19 %. Found: C, 50.93; H, 3.64; N, 2.18 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimeter): 1,436(s) ν(C=N), 1,146(s) ν(C–O), 1,100(s) ν(C–S). M.pt: 143–145 °C.

Ph3PAu{SC(OEt)=NC6H4Me-4} (2)

Yield: 0.278 g (85 %) colourless crystals from the slow evaporation from a dichloromethane/ethanol mixture (1:1 v/v). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 7.54–7.40 (m, br, 15H, Ph3P), 6.83 (d, 2H, o-aryl-H, J CP = 8.04 Hz), 6.73 (d, 2H, m-aryl-H, J CP = 8.20 Hz), 4.34 (q, 2H, OCH2, J = 7.09 Hz), 2.05 (s, 3H, aryl-CH3), 1.33 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.10 Hz) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 163.8 (Cq), 148.7 (Ph, C1), 134.3 (d, o-PC6H5, J CP = 55.3 Hz), 131.6 (d, p-PC6H5, J CP = 9.0 Hz), 131.4 (Ph, C4), 129.5 (Ph, C3), 129.5 (d, i-PC6H5, J CP = 226.8 Hz), 129.1 (d, m-PC6H5, J CP = 45.6 Hz), 121.8 (Ph, C2), 63.8 (OCH2), 20.8 (aryl-CH3), 14.7 (CH3) ppm. 31P{1H}NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 38.0 ppm. Anal. Calc. for C27H25AuNOPS: C, 51.46; H, 4.16; N, 2.14 %. Found: C, 51.68; H, 3.91; N, 2.22 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimeter): 1,431(s) ν(C=N), 1,118(s) ν(C–O), 1,101(s) ν(C–S). M.pt: 131–133 °C.

Ph3PAu{SC(O-iPr)=NC6H4Me-4} (3)

Yield: 0.297 g (89 %) colourless crystals from the slow evaporation from a dichloromethane/methanol mixture (1:1 v/v). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 7.53–7.42 (br m, 15H, Ph3P), 6.83 (d, 2H, o-aryl-H, J CP = 8.04 Hz), 6.72 (d, 2H, m-aryl-H, J CP = 8.16 Hz), 5.28 (sept, 1H, OCH, J = 6.19 Hz), 2.05 (s, 3H, aryl-CH3), 1.32 (d, 6H, CH3, J = 6.20 Hz) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 162.9 (Cq), 148.9 (Ph, C1), 134.2 (d, o-PC6H5, J CP = 55.2 Hz), 131.6 (d, p-PC6H5, J CP = 7.8 Hz), 131.2 (Ph, C4), 129.5 (Ph, C3), 129.5 (d, i-PC6H5, J CP = 226.8 Hz), 129.1 (d, m-PC6H5, J CP = 45.8 Hz), 121.7 (Ph, C2), 70.3 (OCH), 22.1 (CH3), 20.8 (aryl-CH3) ppm. 31P{1H}NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ 37.8 ppm. Anal. Calc. for C28H27AuNOPS: C, 52.18; H, 4.38; N, 2.10 %. Found: C, 52.15; H, 4.25; N, 2.15 %. IR (KBr disc, per centimeter): 1,437(s) ν(C=N), 1,132(s) ν(C–O), 1,093(s) ν(C–S). M.pt: 148–151 °C.

X-ray crystallography

Intensity measurements for a colourless block (0.06 × 0.06 × 0.11 mm) of 3 were made at 100 K on an Agilent Supernova dual diffractometer with an Atlas (Mo) detector (ω scan technique) using graphite monochromatized Mo Kα radiation [35]. The structure was solved by direct methods (SHELXS97 [36] through the WinGX Interface [37]) and refined (anisotropic displacement parameters, H atoms in the riding model approximation and a final weighting scheme of the form w = 1/[σ 2(F 2o ) + 0.018P 2] where P = (F 2o + 2F 2c )/3) with SHELXL97 on F 2 [36]. Crystal data for C29H29AuNOPS: M = 667.53, monoclinic, P21/c, a = 9.7098(3), b = 12.5573(4), c = 21.9413(6) Å, β = 100.931(3)º, V = 2,626.74(14) Å3, Z = 4, D x = 1.688 g cm−3, F(000) = 1,320, μ = 5.763 mm−1, no. meas. data = 10,940, no. unique data = 6,043, R int = 0.023, no. of parameters = 310, R (5,249 data with I ≥ 2σ(I)) = 0.024, wR (all data) = 0.050. Maximum and minimum residual electron density peaks = 0.81 and −0.77 e Å−3. A view of the molecular structure is shown in Fig. 2, drawn at the 50 % probability level with ORTEP-3 for Windows [37], and the overlay diagram (Fig. 3) was drawn with QMol [38]. The crystal packing analysis was conducted with the aid of PLATON [39] and Fig. 4 was drawn with DIAMOND [40].

Screening for antibacterial activity

Antibacterial screening was performed using the disc diffusion method in accordance with the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guideline. A total of 20 bacterial strains were used in this study: Staphylococcus aureus American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 25923, Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Enterococcus faecium ATCC 19434, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Vibrio parahaemolyticus ATCC 17802, Aeromonas hydrophilla ATCC 35654, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 25933, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 13315, Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 35030, Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048, Shigella flexneri ATCC 12022, Shigella sonnei ATCC 9290, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 14028, Salmonella paratyphi A ATCC 9150, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia ATCC 13637 and Citrobacter freundii ATCC 8090. All bacterial cultures were obtained from ATCC. The inoculum suspension of each bacterial strain was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard turbidity (corresponding to approximately 108 CFU/ml) by adding Mueller–Hinton broth. This suspension was then swabbed on the surface of Mueller–Hinton agar plates using a sterile cotton swab. The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO to the test concentration of 1 mg/ml. Sterile 6 mm filter paper discs were aseptically placed on Mueller–Hinton agar surfaces and 10 μl of the dissolved compounds were immediately added to discs. Each plate contained one standard antibiotic paper disc served as positive control, one disc served as negative control (10 μl broth) and one disc served as solvent control (10 μl DMSO). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Antibacterial activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of inhibition zone against the test bacterial strains. Each experiment was performed in duplicate.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the broth microdilution method according to the NCCLS. The tested compounds were serially threefold diluted in DMSO to the test concentrations of 1,000, 330, 110, 37, 12, 4, 1 and 0.5 μg/ml and then placed into each well of a 96-well microplate. An inoculum suspension with density of 105 CFU/ml of exponentially growing bacterial cells was added into each well. The 96-well microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. All tests were performed in triplicate. Four controls comprising medium with standard antibiotic (positive control), medium with DMSO (solvent control), medium with inoculum bacterial cells (negative control), and medium with broth only (negative growth control) were included in each test. Bacterial growth was detected by adding 50 μl of a 0.2 mg/ml p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (INT) indicator solution into each of the microplate wells and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min under aerobic agitation. Where bacterial growth was inhibited, the suspension in the well remained clear after incubation with INT. By contrast, the INT changed from clear to red in the presence of bacterial activity. The lowest concentration of the tested compound which completely inhibited bacterial growth was taken as the MIC. After MIC determination of each tested compound, an aliquot of 100 μl from each well which showed no visible growth was spread onto MHA at 37 °C for 30 min. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was defined as the lowest concentration of the tested compound producing a 99.9 % reduction in bacterial viable count on the MHA.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterisation

Crystallography, NMR and theoretical studies confirm that the ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 molecules exist as amides rather than thiols [33]. The Ph3PAu{SC(OR)=NC6H4Me-4}, for R = Me (1), Et (2) and iPr (3), compounds were prepared by the facile reaction of Ph3PAuCl with the respective ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 in the presence of NaOH in good yields (≥85 %), each as colourless crystals. The compounds are light and air-stable. They are soluble in chlorinated solvents, partially soluble in acetonitrile and DMSO, sparingly soluble in methanol, ethanol and acetone, and insoluble in water.

NMR spectroscopy (1H, 13C{1H} and 31P{1H}) show the expected resonances and integration. Notable in the 1H NMR spectra of 1–3 was the absence of the resonance due to N-H found in ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4, and notable upfield shifts for the OCH and tolyl-Me-H protons. In the 13C{1H} spectra, significant upfield shifts were observed for the quaternary (25 ppm) and O-bound (3–5 ppm) carbon nuclei compared with their positions in the spectra of ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4. These results confirm coordination of anionic forms of the ligands and a significant reduction in delocalisation of π-electron density over the central OC(S)N chromophore compared with that in the ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4 molecules [33]. It is noteworthy that the systematic variation in the OCH (1H) resonances and in the quaternary and O-bound (13C{1H}) resonances that are correlated with the electron-donating ability of R observed in the spectra of ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4, i.e. downfield for R = Me compared with upfield for iPr, persists in the spectra of 1–3. In the 31P{1H} NMR, a single resonance was observed for each of 1–3 at approximately 38.0 ppm, i.e. deshielded with respect to uncoordinated Ph3P (−5.2 ppm). As an indication of the stability of 1–3 in solution, time-dependent 1H NMR spectra were measured. These studies showed that in DMSO solution no change in the resonances occurred over a period of 2 weeks.

Infrared spectroscopy confirmed the absence of ν(N–H) in the spectra of 1–3. Compared to that observed for ROC(=S)N(H)C6H4Me-4, systematic shifts to lower, lower, and higher wavenumber are noted for absorptions due to ν(C–N), ν(C–O) and ν(C–S) in 1–3 consistent with the mode of complexation of the anions indicated in Fig. 1. This is confirmed by a crystal structure determination of 3.

The molecular structure of 3 is illustrated in Fig. 2. The gold atom is linearly coordinated by the phosphane-P1 and thiolate-S1 atoms with bond lengths of 2.2561(7) and 2.3171(7) Å, respectively. The C1–S1 and C1–N1 bond lengths of 1.776(3) and 1.269(4) Å, respectively, have significantly elongated and shortened compared to related “free” thiocarbamide molecules [33], and are consistent with the notion that the molecule was deprotonated during the synthesis and coordinates as a thiolate. The P1–Au–S1 angle of 172.88(3)° deviates significantly from the ideal 180° and this feature is attributed to the close approach of the O1 atom to gold, i.e. Au…O1 is 2.887(2) Å.

Crystal structure determinations have been reported previously for each of 1 [41] and 2 [42]. As seen from the overlay diagram in Fig. 3, a very similar mode of coordination is found for 1 and 3, which conforms to the norm for structures of this type [43]. However, a variation is noted in 2, where the arene ring is oriented towards the gold atom rather than the O1 atom; intra- and intermolecular Au…π(arene) interactions have been reviewed recently [44]. Such variations have been discussed in some detail in the literature and arise owing to the combination of subtle electronic and steric effects of the P-, O- and N-bound substituents [41].

Figure 4 illustrates the crystal packing in 3. Molecules associate into a three-dimensional architecture by a combination of edge-to-face C–H…π interactions, there being no other significant intermolecular interactions of note; see [45] for geometric parameters describing the intermolecular interactions. The interactions pivotally involve the p-tolyl ring in that it forms a donor interaction to a P-bound phenyl ring, and accepts two interactions from two P-bound phenyl rings.

Antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial activity of the gold compounds were determined against a wide variety of pathogens comprising four strains of Gram-positive bacteria and 16 strains of Gram-negative bacteria. The tested bacterial species vary with respect to their disease modality and virulence. Of the 20 tested bacterial species, only four bacterial species that belong to Gram-positive (B. cereus, E. faecalis, E. faecium and S. aureus) showed consistent inhibition zones towards 1–3 in disc diffusion assay; see data in Table 1.

Briefly, no inhibitory activity was detected from 1 to 3 against any of the Gram-negative bacteria. The results revealed the specific effectiveness of the tested compound 1–3 on Gram-positive bacteria (which have thick peptidoglycan as the outermost layer in the cell wall), and not against Gram-negative bacteria (which have an outer membrane composed of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharide). As Gram-positive bacteria are dependent on peptidoglycan for their cell wall protection and to maintain osmotic pressure [46], the mechanism for the antibacterial action of 1–3 might be related to the inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis in the cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria leading to the death of the bacteria.

The serial dilution assay suggested that the inhibitory effects of 1–3 towards different pathogens in the disc diffusion assay were dose dependent. Table 2 collects the MIC and MBC values for the four Gram-positive pathogens in response to treatment with 1–3 and standard antibiotics. The MIC values were in the range of 1–37 μg/ml, which may be considered as high antibacterial activity in comparison with the standard antibiotic tetracycline for which the range in MIC values is 4–37 μg/ml. The most susceptible strains were B. cereus (1–4 μg/ml) and E. faecalis (4 μg/ml), while E. faecium (37 μg/ml) and S. aureus (37 μg/ml) showed the lowest sensitivity towards 1–3.

The MBC, time kill curve and serum bactericidal titre are the in vitro microbiological techniques uses to determine whether an antibacterial agent is bacteriostatic or bactericidal [47]. MBC was the method used in this study to determine the bactericidal activity of the tested compounds towards the inhibited pathogens. According to Levison [48], antibacterial agents are regarded as bactericidal if the MBC is no more than fourfold higher than the MIC. By contrast, the MBC of bacteriostatic agents are many fold higher than their MIC. This is because the bacteriostatic agents only prevent the growth of bacteria, whereas bactericidal agents kill the bacteria [49]. The MBC values of 1–3 were same as their MIC, indicating good bactericidal effects against B. cereus, E. faecalis, E. faecium and S. aureus.

Data from this study suggest that 1–3 could be potent against Bacillus spp., Staphylococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp., an observation in agreement with the recent report of Sordo et al. [31], who found high antibacterial activity of certain gold sulfanylcarboxylates against Bacillus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. Previous reports suggested the potential importance of bactericidal drugs for treating bacterial infections in severely neutropenic patients, who exhibit abnormally low level of neutrophils in the blood and a lack of host defences to clear the infecting bacteria if bacteriostatic drugs are introduced [47, 48, 50]. In addition, it is noted that the Gram-positive bacteria are an important cause of infection in neutropenic patients [47, 51, 52].

In summary, the easily synthesised, stable and crystalline gold compounds 1–3 may be potentially developed as alternative bactericidal agents for use in the treatment of microbial disease especially for recently emerging multidrug-resistant strains of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [49] and Enterococcus spp. [53] which are known to cause life-threatening infections in humans. Efforts are underway to explore the antibacterial activities of related derivatives with variations in P-, O-, and N-substituents and into possible mechanisms of action.

References

Hemaiswarya S, Kruthiventi AK, Doble M (2008) Synergism between natural products and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Phytomedicine 15:639–652. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2008.06.008

Editor (2013) Editorial: the antibiotic alarm. Nature. doi:10.1038/495141a

Jones RN, Pfaller MA (1998) Bacterial resistance: a worldwide problem. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 31:379–388. doi:10.1016/S0732-8893(98)00037-6

Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Doern GV, Sader HS, Kugler KC, Beach ML (1999) Survey of blood stream infections attributable to Gram-positive cocci: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in 1997 in the United States, Canada, and Latin America from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. SENTRY Participants Group. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 33:283–297. doi:10.1016/S0732-8893(98)00149-7

Otto M (2010) Staphylococcus colonization of the skin and antimicrobial peptides. Expert Rev Dermatol 5:183–195. doi:10.1586/edm.10.6

Jones RN (2003) Global epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance among community-acquired and nosocomial pathogens: a five-year summary from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2001). Semin Respir Crit Care Med 24:121–134. doi:10.1055/s-2003-37923

Eisler E (2003) Chrysotherapy: a synoptic review. Inflamm Res 52:487–501. doi:10.1007/s00011-002-1208-2

Kean WF, Kean IRL (2008) Clinical pharmacology of gold. Inflammopharmacology 16:112–125. doi:10.1007/s10787-007-0021-x

Pacheco EA, Tiekink ERT, Whitehouse MW (2009) Gold compounds and their applications in medicine. In: Mohr F (ed) Gold chemistry. Applications and future directions in the life sciences. Wiley, Germany, pp 283–319

Berners-Price SJ (2011) Gold-based therapeutic agents: a new perspective. In: Alessio E (ed) Bioinorganic medicinal chemistry. Wiley, Weinheim, pp 197–222

Bhabak K, Bhuyan BJ, Mugesh G (2011) Bioinorganic and medicinal chemistry: aspects of gold(I)-protein complexes. Dalton Trans 40:2099–2111. doi:10.1039/C0DT01057J

Trávníček Z, Štarha P, Vančo J, Šilha T, Hošek J, Suchý P Jr, Prazanova G (2012) Anti-inflammatory active gold(I) complexes involving 6-substituted-purine derivatives. J Med Chem 55:4568–4579. doi:10.1021/jm201416p

Pacheco EA, Tiekink ERT, Whitehouse MW (2009) Biomedical applications of gold and gold compounds. In: Corti C, Holliday R (eds) Gold: science and applications. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 217–230

Berners-Price SJ, Filipovska A (2011) Gold compounds as therapeutic agents for human diseases. Metallomics 3:863–873. doi:10.1039/c1mt00062d

Ott I (2009) On the medicinal chemistry of gold complexes as anticancer drugs. Coord Chem Rev 253:1670–1681. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.019

Fregona D, Ronconi L, Aldinucci D (2009) Groundbreaking gold(III) anticancer agents. Drug Discov Today 14:1075–1076

Tiekink ERT (2002) Gold derivatives for the treatment of cancer. Crit Rev Hematol Oncol 42:225–248. doi:10.1016/S1040-8428(01)00216-5

Tiekink ERT (2003) Gold compounds in medicine: potential anti-tumour agents. Gold Bull 36:117–124. doi:10.1007/BF03215502

Fricker SP (1996) Medical uses of gold compounds: past, present and future. Gold Bull 29:53–60. doi:10.1007/BF03215464

Che C-M, Sun RW-Y (2011) Therapeutic applications of gold complexes: lipophilic gold(III) cations and gold(I) complexes for anti-cancer treatment. Chem Commun 47:9554–9560. doi:10.1039/C1CC10860C

Milacic V, Dou QP (2009) The tumor proteasome as a novel target for gold(III) complexes: implications for breast cancer therapy. Coord Chem Rev 253:1649–1660. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.032

Bindoli A, Rigobello MP, Scutari G, Gabbiani C, Casini A, Messori L (2009) Thioredoxin reductase: a target for gold compounds acting as potential anticancer drugs. Coord Chem Rev 253:1692–1707. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.026

Gabbiani C, Cinellu MA, Maiore L, Massai L, Scaletti F (2012) Chemistry and biology of three representative gold(III) compounds as prospective anticancer agents. Inorg Chim Acta 393:115–124. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2012.07.016

Madeira JM, Gibson DL, Kean WF, Klegeris A (2012) The biological activity of auranofin: implications for novel treatment of diseases. Inflammopharmacology 20:297–306. doi:10.1007/s10787-012-0149-1

Novelli F, Recine M, Sparatore F, Juliano C (1999) Gold(I) complexes as antimicrobial agents. Il Farmaco 54:232–236. doi:10.1016/S0014-827X(99)00019-1

Noguchi R, Hara A, Sugie A, Nomiya K (2006) Synthesis of novel gold(I) complexes derived by AgCl-elimination between [AuCl(PPh3)] and silver(I) heterocyclic carboxylates, and their antimicrobial activities. Molecular structure of [Au(R, S-Hpyrrld)(PPh3)] (H2pyrrld = 2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxylic acid). Inorg Chem Commun 9:355–359. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2006.01.001

Marques LL, Oliveira GMD, Lang ES, Campos MMAD, Gris LRS (2007) New gold(I) and silver(I) complexes of sulfamethoxazole: synthesis, X-ray structural characterization and microbiological activities of triphenylphosphine(sulfamethoxazolato-N2)gold(I) and (sulfamethoxazolato)silver(I). Inorg Chem Commun 10:1083–1087. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2007.06.005

Ray S, Mohan R, Singh JK, Samantaray MK, Shaikh MM, Panda D, Ghosh P (2007) Anticancer and antimicrobial metallopharmaceutical agents based on palladium, gold, and silver N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. J Am Chem Soc 129:15042–15053. doi:10.1021/ja075889z

Nomiya K, Takahashi S, Noguchi R (2000) Synthesis and crystal structure of a hexanuclear silver(I) cluster [Ag(Hmna)]6.4H2O (H2mna=2-mercaptonicotinic acid) and a supramolecular gold(I) complex H[Au(Hmna)2] in the solid state, and their antimicrobial activities. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans 2000:2091–2097. doi:10.1039/B001664K

Corbi PP, Quintão FA, Ferraresi DKD, Lustri WR, Amaral AC, Massabni AC (2010) Chemical, spectroscopic characterization, and in vitro antibacterial studies of a new gold(I) complex with N-acetyl-l-cysteine. J Coord Chem 63:1390–1397. doi:10.1080/00958971003782608

Barreiro E, Casas JS, Couce MD, Sánchez A, Seoane R, Perez-Estévez A, Sordo J (2012) Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of gold(I) sulfanylcarboxylates. Gold Bull 45:23–34. doi:10.1007/s13404-011-0040-7

Dinger MB, Henderson W (1998) Organogold(III) metallacyclic chemistry. Part 41. Synthesis, characterisation, and biological activity of gold(III)-thiosalicylate and -salicylate complexes. J Organomet Chem 560:233–243. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(98)00493-8

Ho SY, Bettens RPA, Dakternieks D, Duthie A, Tiekink ERT (2005) Prevalence of the thioamide {…H-N-C=S}2 synthon—solid-state (X-ray crystallography), solution (NMR) and gas-phase (theoretical) structures of O-methyl-N-aryl-thiocarbamides. CrystEngComm 7:682–689. doi:10.1039/B514254G

Hall VJ, Siasios G, Tiekink ERT (1993) Triorganophosphinegold(I) carbonimidothioates. Aust J Chem 46:561–570. doi:10.1071/CH9930561

CrysAlisPro (2010) Agilent Technologies, Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England

Sheldrick GM (2008) A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A64:112–122. doi:10.1107/S0108767307043930

Farrugia LJ (2012) WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: an update. J Appl Crystallogr 45:849–854. doi:10.1107/S0021889812029111

Gans J, Shalloway D (2001) Qmol: a program for molecular visualization on Windows based PCs. J Mol Graph Model 19:557–559. doi:10.1016/S1093-3263(01)00090-0

Spek AL (2003) Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J Appl Crystallogr 36:7–13. doi:10.1107/S0021889802022112

Brandenburg K (2006) DIAMOND. Crystal Impact GbR, Bonn

Kuan FS, Ho SY, Tadbuppa PP, Tiekink ERT (2008) Electronic and steric control over Au…Au, C–H…O and C–H…π interactions in the crystal structures of mononuclear triarylphosphinegold(I) carbonimidothioates: R3PAu[SC(OMe)=NR′] for R′ = Ph, o-tol, m-tol or p-tol, and R′ = Ph, o-tol, m-tol, p-tol or C6H4NO2-4. CrystEngComm 10:548–564. doi:10.1039/b717198f

Tadbuppa PP, Tiekink ERT (2009) [(Z)-O-Ethyl-N-(p-tolyl)thiocarbamato-κS](triphenylphosphine)-κP]gold(I). Acta Crystallogr E 65:m1587. doi:10.1107/S1600536809047618

Ho SY, Cheng EC-C, Tiekink ERT, Yam VW-W (2006) Luminescent phosphine gold(I) thiolates: correlation between crystal structure and photoluminescent properties in [R3PAu{SC(OMe)=NC6H4NO2-4}] (R = Et, Cy, Ph) and [(Ph2P-R-PPh2){AuSC(OMe)=NC6H4NO2-4}2] (R = CH2, (CH2)2, (CH2)3, (CH2)4, Fc). Inorg Chem 45:8165–8174. doi:10.1021/ic0608243

Caracelli I, Zukerman-Schpector J, Tiekink ERT (2013) Supramolecular synthons based on gold…π(arene) interactions. Gold Bull. doi:10.1007/s13404-013-0088-7

Geometric parameters characterising the intermolecular C–H…π interactions in the crystal structure of 3: C4–H4…Cg(C24-C29)i = 2.69 Å, C4…Cg(C24-C29)i = 3.473(4) Å, angle at H = 140°; C19–H19…Cg(C2-C7)ii = 2.79 Å, C19…Cg(C2-C7)ii = 3.662(3) Å, angle at H = 153°; and C27–H27…Cg(C2-C7)iii = 2.82 Å, C27…Cg(C2-C7)iii = 3.515(3) Å, angle at H = 131°. Symmetry operations: i, 2-x, ½+y, ½-z; ii, 2-x, -½+y, ½-z; and iii, x, 1½-y, ½+z

Schneewind O, Missiakas DM (2012) Protein secretion and surface display in Gram positive bacteria. Phil Trans R Soc B 367:1123–1139. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0210

Pankey GA, Sabath LD (2004) Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis 38:864–870. doi:10.1086/381972

Levison ME (2004) Pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial drugs. Infect Dis Clin N Am 18:451–465. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2004.04.012

French GL (2006) Bactericidal agents in the treatment of MRSA infections—the potential role of daptomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother 58:1107–1117. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl393

Klastersky J (1986) Concept of empiric therapy with antibiotic combinations. Am J Med 80:2–12

Brown AE (1984) Neutropenia, fever, and infection. Am J Med 76:421–428. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90661-2

Pizzo PA, Hathorn JW, Hiemenz J, Browne M, Commers J, Cotton D, Gress J, Longo D, Marshall D, McKnight J, Rubin M, Skelton J, Thaler M, Wesley R (1986) A randomized trial comparing ceftazidime alone with combination antibiotic therapy in cancer patients with fever and neutropenia. N Engl J Med 315:552–558. doi:10.1056/NEJM198608283150905

Arias CA, Contreras GA, Murray BE (2010) Management of multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:555–562. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03214.x

Acknowledgments

The Ministry of Higher Education (Malaysia) is thanked for funding medicinal chemistry studies through the High-Impact Research scheme (UM.C/HIR-MOHE/SC/12). Support from the University of Malaya is also gratefully acknowledged (UMRG: RG125).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeo, C.I., Sim, JH., Khoo, CH. et al. Pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria are highly sensitive to triphenylphosphanegold(O-alkylthiocarbamates), Ph3PAu[SC(OR)=N(p-tolyl)] (R = Me, Et and iPr). Gold Bull 46, 145–152 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13404-013-0091-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13404-013-0091-z