Abstract

Background

Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALRP) is currently accepted as the preferred minimally invasive surgical treatment for localised prostate cancer, with optimal oncologic and functional results. Despite growing surgical experience, reduced postoperative morbidity and hospital stays, RALRP-related complications may occur, which are severe in 5–7 % of patients and sometimes require reoperation. Therefore, in hospitals with an active urologic surgery, urgent diagnostic imaging is increasingly requested to assess suspected early complications following RALRP surgery.

Methods

Based upon our experience, this pictorial review discusses basic principles of the surgical technique, the optimal multidetector CT (MDCT) techniques to be used in the postoperative urologic setting, the normal postoperative anatomy and imaging appearances.

Results

Afterwards, we review and illustrate the varied spectrum of RALRP-related complications including haemorrhage, urinary leaks, anorectal injuries, peritoneal changes, surgical site infections, abscess collections and lymphoceles, venous thrombosis and port site hernias.

Conclusion

Knowledge of surgical procedure details, appropriate MDCT acquisition techniques, and familiarity with normal postoperative imaging appearances and possible complications are needed to correctly perform and interpret early post-surgical imaging studies, particularly to identify those occurrences that require prolonged in-hospital treatment or surgical reintervention.

Teaching points

• Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy allows minimally invasive surgery of localised cancer

• Urologic surgeons may request urgent imaging to assess suspected postoperative complications

• Main complications include haemorrhage, urine leaks, anorectal injuries, infections and lymphoceles

• Correct multidetector CT techniques allow identifying haematomas, active bleeding and extravasated urine

• Imaging postoperative complications is crucial to assess the need for surgical reoperation

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

During the last 20 years, the surgical treatment of prostate cancer (PC) evolved from open to laparoscopic prostatectomy. Currently, robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALRP) represents the preferred, minimally invasive surgery for localised PC. Since its introduction in 2000, RALRP has increasingly gained acceptance and popularity among urologists and is currently considered a safe, reproducible procedure with a limited learning curve for experienced surgeons and an acceptable complication rate in experienced hands [1–3].

During the last decade, several series have reported favourable results with RALRP compared to radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) in terms of reduced blood loss, postoperative pain and hospital stay, surgical margins (which are found positive in approximately 20 % of patients), preserved urinary continence and erectile function. However, despite the reduced morbidity, optimal oncologic and functional results, RALRP-associated complications do occur. The reported overall RALRP complication rates greatly vary (in the range 14.6–42 % of patients) according to operator experience and centre case load, criteria and severity of complications. Preoperative predictive factors include comorbidities, advanced age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values and Gleason score. The majority (approximately two-thirds) of occurrences are classified as minor complications (Clavien classes 1 and 2, including prolongation of postoperative course, drug or bedside treatment), but major (Clavien classes 3 to 5) complications occur in 5–7 % and require reoperation in 3 % of patients respectively [1, 2, 4–7].

Aim

In hospitals with an active urologic surgical practice, radiology departments are increasingly requested to assess suspected early or delayed postoperative complications following RALRP. Based upon our experience, this article discusses basic principles of surgical technique and the optimal multidetector CT (MDCT) techniques in this setting, and reviews the normal postoperative imaging appearances and the spectrum of possible complications, to provide radiologists with an increased familiarity with postoperative imaging of RALRP patients.

Surgical technique notes

The daVinci surgical system (Intuitive Surgical; Mountain View, CA, USA) includes a surgeon’s console, a patient-side robotic cart with four arms manipulated by the surgeon and a high-definition three-dimensional vision system that provides a 10- to 12× magnification stereoscopic view of the operative field. The device senses the hand instructions, filters tremor, and translates and transmits movement to manipulate the tiny proprietary instruments, to provide the surgeon with enhanced vision and dexterity [1–3].

Although a description of the surgical technique is beyond the scope of this pictorial review, some remarks are useful to the radiologist. Knowledge of procedural details (including the surgical approach, the use of surgical clips or patches, and if concomitant lymphadenectomy was performed) is necessary, since they result in key differences in postoperative imaging appearances and complications observed. According to surgeon’s preference and familiarity, radical prostatectomy can be performed using either a transperitoneal (TP) or extraperitoneal (EP) approach through the prevesical space of Retzius. In both cases, a vesico-urethral anastomosis (VUA) is created between the urinary bladder and the membranous urethra. With the latter approach urine leaks are confined to the extraperitoneal space, whereas the TP approach creates two potential routes of communication from the VUA to the peritoneal cavity, respectively anterior and posterior to the bladder [8–10].

According to both literature and our personal experience, the commonest indications for postoperative imaging include abdominal, pelvic and/or perineal pain, clinical or laboratory signs of blood loss, persistent ileus, fever and/or abnormal acute phase reactants, rising serum creatinine, high output from drainage tube and low urine output from a Foley catheter [4–7].

Imaging techniques

Often performed as first-line investigation in postoperative urologic patients, ultrasound may quickly provide an overview of the urinary tract and assess the presence of peritoneal effusion and of space-occupying collections. However, ultrasound may be hampered by large body size, uncooperation and overlying bowel gas. Conversely, MDCT consistently provides a comprehensive visualisation of the entire abdomen and pelvis and therefore in the vast majority of cases represents the preferred modality to search for possible postoperative complications. Basically, in urologic patients a postoperative MDCT study should include: (1) a preliminary unenhanced acquisition to detect hyperattenuating blood and abnormal air collections; (2) arterial- and venous-phase images after intravenous contrast medium (CM) injection to assess the solid organs and identify extravascular CM indicating active bleeding; (3) excretory phase imaging obtained at least 5–20 minutes (up to 1-2 hours) after CM, in order to demonstrate the opacified urinary cavities and detect iodinated urine leaks and urinomas. Most usually interpreted on a dedicated workstation, MDCT studies should be complemented with multiplanar reformations and three-dimensional volume-rendering (3D-VR) images to effectively depict the postoperative anatomy and salient findings [6, 11–13].

In the early phases of our experience, most postoperative RALRP patients were investigated using a classical multiphasic MDCT exam protocol. When renal function impairment contraindicates CM administration, an unenhanced MDCT acquisition is helpful to demonstrate the postoperative anatomy and abnormal haemorrhagic or fluid space-occupying collections, although it cannot detect active bleeding and extraluminal urine. More recently, to limit the radiation dose erogated during multiphasic acquisitions, split-bolus MDCT urography protocols have been developed that allow for combined renal vascular, parenchymal and excretory acquisition. In several cases, we successfully adopted the time- and dose-efficient triple-bolus MDCT-urography protocol described by Kekelidze et al., which includes preliminary unenhanced scans, an initial 30 ml CM bolus injected at 2 ml/s flow for urinary opacification, a 7-min delay, a second (50 ml at 1.5 ml/s) and third (65 ml at 3 ml/s) CM injection separated 20 s from each other to provide parenchymal and vascular visualisation respectively, followed by a single MDCT volumetric acquisition. Therefore, triple-bolus MDCT urography provides simultaneous renovascular, corticomedullary, nephrographic and excretory imaging with a reduced effective radiation dose compared to the usual multiphasic MDCT protocols [13, 14].

Due to its intrinsically high contrast resolution, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides an excellent visualisation of the normal post-prostatectomy anatomy and of possible neoplastic recurrence [9]. In the emergency setting, the use of MRI is limited by lengthy examination time, scanner availability, constraints and artefacts in acutely ill patients. Compared to MRI, with appropriate acquisition techniques MDCT provides quicker reliable identification of blood collections, extravasated urine and active bleeding [10, 12, 13].

Furthermore, in patients with suspicion of VUA leak an additional focussed investigation with conventional radiographic cystography or MDCT cystography is recommended. At our department diluted iodinated CM to be used during MDCT cystography is prepared by removing 40–50 ml of normal saline from a 500-ml bag and injecting a similar amount of non-ionic contrast agent (such as 350 mgI/ml iomeprol or 370 mgI/ml iopromide) into the same saline solution bag. The bag is then connected to standard tubing for intravenous infusions, filling the tube with diluted contrast to avoid instilling air in the bladder. With the patient supine on the CT scanner table, slow retrograde infusion is obtained by gravity. Differently from conventional MDCT cystography to investigate bladder trauma and spontaneous colovesical fistulas, in postoperative patients the injected CM volume should not exceed 150 ml because of concern about excessive pressure on the newly created VUA. The volumetric MDCT acquisition at sufficient bladder distension is visualised with multiplanar image reformations at CT angiography window settings (width 600–900 level 150–300 Hounsfield Units, HU) and by maximum intensity projection (MIP) or 3D-VR techniques. The only potential pitfall of this technique is the possible occlusion of a limited anastomotic dehiscence by the Foley catheter balloon [8, 15, 16].

Normal postoperative anatomy and imaging findings

As best demonstrated with MRI, following prostatectomy the urinary bladder base and levator muscle sling descend caudally and anteriorly into the resected prostate bed. In the early postoperative setting, multiplanar MDCT studies show similar appearances, including the presence of metallic surgical clips and seminal vesicle remnants (Fig. 1). The fat planes surrounding the bladder base and VUA should be carefully assessed for asymmetry or presence of abnormal air, haemorrhagic or fluid collections. When unknown to the radiologist, the presence of inhomogeneous-density regenerated oxidised cellulose patches (Tabotamp ®) may cause diagnostic dilemmas and be misinterpreted as enteral material suggesting intestinal perforation (Figs. 1, 2).

Usual early postoperative appearance of the prostatic surgical bed after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALRP) in a 54-year-old patient with laboratory evidence of blood loss. Unenhanced MDCT images (a, b) show Foley catheter still in place, seminal vesicle remnants more prominent on the right side (arrowhead in a), unremarkable appearance of the prostatic bed fat (*) and levator muscle slings (arrows). Descent of the bladder base is better depicted on sagittal reformatted MDCT image (b) and on T2-weighted MRI images (c, d) obtained a month later, with appearance of low-intensity fibrotic signal (+) surrounding the vesico-urethral anastomosis (VUA)

In patients operated on through a TP surgical approach, during the early postoperative days minimal or moderate residual intraperitoneal air is commonly observed, often associated with multiple air-fluid levels of the small bowel consistent with adynamic ileus.

Bleeding complications

One of the commonest postoperative complications (reported in 5.3 % of RALRP patients), haemorrhage is heralded by the identification of hyperattenuating blood on unenhanced MDCT images. Recent haematoma usually shows 45–75 HU attenuation due to its high protein content and thus appears hyperdense compared to muscles. Subsequently, progressive haemoglobin lysis leads to a “geographic” mixed-density appearance. In most cases, postoperative haemorrhage following RALRP is detected in the prostatic bed and/or peritoneal cul-de-sac (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Additionally, focal CM extravasation consistent with active bleeding is sometimes observed in arterial or venous phase enhanced acquisitions (Fig. 4) [17, 18].

Early postoperative appearances of the prostatic bed following RALRP in two different patients. In a 73-year-old man with oliguria and impaired renal function (4.1 mg/dl serum creatinine), the VUA is identified on unenhanced MDCT images (a, b) by the presence of metallic clips. Note the Foley catheter in place (thin arrows), minimally increased density of the prostatic bed fat (*) and right ureteral stent in (b). In a 45-year-old man investigated 36 h after surgery because of significant blood loss, axial (a) and coronal (b) images from triple-bolus MDCT urography show symmetric inhomogeneous densities (arrowheads) in the prostatic bed, corresponding to regenerated oxidised cellulose patches (Tabotamp ®), and minimal blood effusion in the peritoneal cul-de-sac (*)

Sizeable hyperattenuating (55–60 HU) collection consistent with postoperative haematoma (*) occupies the prostatic surgical bed 7 days after RALRP in a 61-year-old patient with pelvic pain, laboratory signs of blood loss and acute inflammation. Enhanced MDCT acquisition (b) failed to detect contrast medium (CM) extravasation indicating active bleeding. Moderate haemoperitoneum is present in the peritoneal cul-de-sac and perisplenic area. Conservative treatment included blood transfusions

In a 64-year-old patient investigated with multiphasic MDCT because of blood loss on the 4th postoperative day after RALRP, arterial-phase axial (a) and coronal (b), venous-phase coronal (c) images show blood attenuation collection (*) in the prostatic surgical bed, with a focal contrast extravasation (arrowheads) indicating active bleeding. Successful conservative treatment required a prolonged hospitalisation

Alternatively, postoperative haematomas may involve the subperitoneal compartment or the abdominal wall muscles (Fig. 5). Multiplanar MDCT reformations are helpful to visualise the blood collections in their entire size and relationship with nearby structures. Hyperattenuating effusion in the peritoneal cavity represents haemoperitoneum, which is usually most dense in the Douglas’ cul-de-sac and dependent compartments (Fig. 5, 6). Massive haemorrhage, active bleeding and haemoperitoneum represent alarming signs that should prompt immediate consultation and warrant urgent surgical treatment in most cases [19].

Extensive, inhomogeneously hyperattenuating subperitoneal haematoma (* in a, b) causing posterior dislocation of the urinary bladder in a 62-year-old man 48 h after RALRP, being investigated with MDCT because of severe blood loss. In absence of active bleeding and haemoperitoneum, prolonged hospitalisation with a Foley catheter in place was required, without invasive treatment. Rectus abdominis muscle haematoma (arrowhead in c), associated with mesenterial (* in c) and peritoneal (* in d) haemorrhagic effusion in a 54-year-old patient with blood loss (same patient as in Fig. 1). Surgery was needed to control bleeding from an anterior abdominal wall vessel

Hyperattenuating haemoperitoneum (*) in the pelvic cul-de-sac and perisplenic area, minimal residual intraperitoneal air (+ in C) in a 57-year-old patient being investigated with MDCT urography 48 h after RALRP because of blood loss. Active CM extravasation was not appreciated. Surgical reoperation was required to control pelvic bleeding from minor vessel injury

Urinary leaks

During RALRP, the VUA is created with a Foley catheter in place. Traditionally, radiographic voiding cystography has been routinely performed after radical prostatectomy before catheter removal. Currently, the optimal interval between surgery and Foley catheter removal has still not been established. Early patient discharge and removal of the Foley catheter 8–10 days after RARLP without routine cystography are now accepted practice [6, 20–22].

Following RALRP, urinary extravasation at the VUA occurs with an incidence of 8.6–13.6 %, which is similar or better than that reported after RRP. In the majority of cases the VUA leak extends from the surgical bed to the extraperitoneal space (Fig. 7), may opacify a pelvic fluid collection and is treated conservatively. The intraperitoneal VUA leak is uniquely associated with RALRP and not with RRP, and very rare (0.7–1.4 % of patients, fewer than onr out of ten leaks) compared to extraperitoneal occurrences although its incidence is probably underestimated at fluoroscopic cystography because of the poor conspicuity of diluted CM into ascites. Conversely, MDCT cystography allows easy assessment of the site and extent of urine leaks and is particularly suited to demonstrate intraperitoneal leaks around the bowel loops and into the paracolic gutters (Fig. 8). In the setting of recent RALRP, the presence of ascites should raise a suspicion of intraperitoneal urinary extravasation and mandates investigation with MDCT urography (Figs. 8, 9) or MDCT cystography. Urinary VUA leaks invariably dictate prolonged bladder catheterisation, and imaging-guided drainage is needed in exceptional (less than 1 %) cases [8, 11, 15, 23].

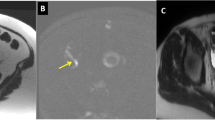

Extraperitoneal VUA leak in a 70-year-old patient with recent RALRP and intraoperative repair of recto-urethral fistula (RUF). On axial enhanced MDCT image (a) air (arrowhead) is observed between the anorectal junction and the VUA level. At MDCT cystography anterior (thin arrow) and posterior (arrow) extraperitoneal CM extravasations indicate double VUA leak. After prolonged catheterisation to heal the VUA, persistent RUF was confirmed by anoscopy and elective surgical repair was planned

Intraperitoneal urine leak in a 68-year-old patient with oliguria, abdominal pain and distension, severe renal impairment (3.2 mg/dl creatinine) 8 days after RALRP. Initial unenhanced MDCT shows the urinary bladder appeared contracted with a Foley catheter in place (arrowheads), water-attenuation ascites (*) and minimal fluid (+) anteriorly to the surgical bed without abnormal blood or abscess collections. Five days later, with improved renal function during conservative treatment, CM-enhanced MDCT urography (c, b) showed decreased peritoneal effusion, anterior VUA leak (thin arrow in c) causing prevesical iodinated urine collection and opacification of peritoneal effusion (arrows in d). The patient recovered after long-term positioning of bilateral ureteral stents and a Foley catheter

Abundant fluid-attenuation ascites (*) in a 47-year-old male investigated with MDCT urography 5 days after RALRP because of abdominal distension and local pain. Both urinary tracts appear patent and non-dilated. With the Foley catheter in place, the urinary bladder is well distended and opacified without appreciable urinary leak. The patient was discharged without any further treatment

Huge fluid attenuation collection that extends from the left posterior pararenal space to the ipsilateral pelvis (*) on unenhanced (a) and CM-enhanced (b) MDCT acquisitions in a 70-year-old patient with fever and lumbar pain 8 days after RARLP. In the excretory phase (c–f, including a volume-rendering 3D image) the collection is filled with enhanced urine, indicating urinoma from ureteral injury (arrows in e, f). Note displacement of the left kidney in a, d, of the urinary bladder in f. Surgical treatment included drainage of the urinoma and ureterocystostomy

Ureteral injury is an exceptional occurrence during RALRP, which can occur secondary to seminal vesicle dissection, extensive lymphadenectomy or bladder neck reconstruction. The resulting urinomas appear at MDCT as more or less confined fluid attenuation collections that may be sometimes misinterpreted as loculated ascites, but get filled by iodinated urine in the excretory phase acquisition. Furthermore, the site and features of the collecting system injury may be exquisitely depicted by multiplanar MIP or 3D-VR reconstructions (Fig. 10), thus allowing optimal operative treatment planning. Although small-sized urinomas usually reabsorb spontaneously, large collections need surgical or percutaneous treatment to prevent superinfection [10–12].

Anorectal injuries

Although exceptional (reported in 0.2–1 % of patients), bowel injuries represent the most feared complications of RALRP. Most occurrences are detected intraoperatively and treated with primary closure, or may occasionally require colostomy. Unrecognised recto-urethral fistulas (RUF) may manifest with pneumaturia, fecaluria, haematuria, intractable urinary infection and sometimes sepsis. At MDCT imaging, the RUF may be directly visualised as an abnormal communication filled by air or enhanced urine (Figs. 7 and 11). In the majority of cases RUFs represent an indication for surgical repair [6, 10, 24, 25].

RUF in a 67-year-old man with recent RALRP and persistent sepsis. Unenhanced MDCT image (a) shows a large air-filled collection (*) from a focal discontinuity of the anterior wall in the distal rectum (arrow). RUF is confirmed during MDCT cystography (b), without appreciable urinary leaks. Surgical repair was required

Postoperative collections

The differential diagnosis of postoperative pelvic collections after urologic surgery includes urinoma, abscess, lymphocele and haematoma. More uncommon than with RRP, surgical site infections occur in 0.6 % of patients after RALRP. In our experience, the detection of fluid or mixed non-haemorrhagic collections in the surgical bed in a postoperative patient with fever and abnormal acute phase reactants is consistent with local infection (Fig. 12) [26–28].

Sizeable bilateral fluid-attenuating collections (+), the largest on the right side containing small flecks of air, extending upwards from the prostatic bed in a 57-year-old patient with persistent fever 7 days after RALRP. Diagnosis of surgical site infection was confirmed by clinical, laboratory and imaging improvement during intensive antibiotic treatment

Relatively common following pelvic lymphadenectomy, lymphoceles are encountered more frequently in patients operated on with an EP approach, although their incidence is reportedly lower with RALRP compared to open surgery. Although most occurrences are poorly symptomatic and resolve spontaneously, lymphoceles are often sizeable (nearly 60 % over 4 cm) and sometimes (18 % of cases) bilateral. At MDCT, lymphoceles appear as thin-walled, homogeneous fluid-attenuating collections in the site of nodal dissection, which may be indicated by the presence of surgical clips (Fig. 13). Large (>5 cm) lymphoceles causing pelvic discomfort, bladder compression, leg pain and weakness may require percutaneous or surgical drainage. An abscess is differentiated from a lymphocele by its thickened, enhancing wall (Fig. 13) [6, 28, 29].

Bilateral pelvic collections in a 57-year-old patient investigated with MDCT 4 weeks after RALRP because of persistent fever, leg oedema and pain. A 4.5-cm collection with thick, enhancing walls (arrows in a) consistent with an abscess is seen abutting the left external iliac vessels, whereas the bilateral fluid-attenuating collections with thin, regular walls indicate lymphoceles in the site of nodal dissection (* in b). Combined transperineal and surgical drainage was performed. More caudally, a filling defect in the left femoral vein indicating thrombosis is detected (arrowhead in c). In a different 76-year-old patient with clinical suspicion of postoperative ileus 4 days after RALRP, MDCT shows abdominal wall emphysema (+) and massive fluid overdistension of small bowel loops with air-fluid levels caused by trocar (port site) hernia (thin arrow in d)

Miscellaneous complications

In our experience, despite anti-thrombotic prophylaxis postoperative venous thrombosis of the legs is commonly observed in RARLP patients. Therefore, MDCT images should be carefully scrutinised for filling defects of the iliac-femoral veins (Fig. 13). Finally, in patients with symptoms or signs of bowel dysfunction the possibility of trocar (port site) hernia causing small bowel obstruction should be considered (Fig. 13) [30, 31].

Conclusion

Urgent diagnostic imaging is increasingly requested by urologic surgeons when postoperative complications are suspected after RALRP. Knowledge of the surgical procedure details, appropriate MDCT acquisition techniques and special interpretation care are needed, particularly to identify postoperative haemorrhage, active bleeding, extravasated urine and infections. Furthermore, radiologists should be familiar with the usual postoperative imaging appearances and the varied spectrum of possible complications, particularly to identify those occurrences that require prolonged in-hospital treatment or surgical reoperation [10, 11].

References

Di Pierro GB, Baumeister P, Stucki P et al (2011) A prospective trial comparing consecutive series of open retropubic and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in a centre with a limited caseload. Eur Urol 59:1–6

Lebeau T, Roupret M, Ferhi K et al (2011) Assessing the complications of laparoscopic robot-assisted surgery: the case of radical prostatectomy. Surg Endosc 25:536–542

Ficarra V, Novara G, Fracalanza S et al (2009) A prospective, non-randomized trial comparing robot-assisted laparoscopic and retropubic radical prostatectomy in one European institution. BJU Int 104:534–539

Agarwal PK, Sammon J, Bhandari A et al (2011) Safety profile of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a standardized report of complications in 3317 patients. Eur Urol 59:684–698

Novara G, Ficarra V, D’Elia C et al (2010) Prospective evaluation with standardised criteria for postoperative complications after robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 57:363–370

Lasser MS, Renzulli J 2nd, Turini GA 3rd et al (2010) An unbiased prospective report of perioperative complications of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology 75:1083–1089

Fischer B, Engel N, Fehr JL et al (2008) Complications of robotic assisted radical prostatectomy. World J Urol 26:595–602

Kawamoto S, Allaf M, Corl FM et al (2012) Anastomotic leak after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: evaluation with MDCT cystography with multiplanar reformatting and 3D display. AJR Am J Roentgenol 199:W595–601

Allen SD, Thompson A, Sohaib SA (2008) The normal post-surgical anatomy of the male pelvis following radical prostatectomy as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol 18:1281–1291

Yablon CM, Banner MP, Ramchandani P et al (2004) Complications of prostate cancer treatment: spectrum of imaging findings. Radiographics 24(Suppl 1):S181–194

Titton RL, Gervais DA, Hahn PF et al (2003) Urine leaks and urinomas: diagnosis and imaging-guided intervention. Radiographics 23:1133–1147

Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S et al (2002) Urinomas caused by ureteral injuries: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging 27:88–92

Kekelidze M, Dwarkasing RS, Dijkshoorn ML et al (2010) Kidney and urinary tract imaging: triple-bolus multidetector CT urography as a one-stop shop–protocol design, opacification, and image quality analysis. Radiology 255:508–516

Van Der Molen AJ, Cowan NC, Mueller-Lisse UG et al (2008) CT urography: definition, indications and techniques. A guideline for clinical practice. Eur Radiol 18:4–17

Tonolini M, Bianco R (2012) Multidetector CT cystography for imaging colovesical fistulas and iatrogenic bladder leaks. Insights Imaging 3:181–187

Chan DP, Abujudeh HH, Cushing GL Jr et al (2006) CT cystography with multiplanar reformation for suspected bladder rupture: experience in 234 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 187:1296–1302

Furlan A, Fakhran S, Federle MP (2009) Spontaneous abdominal hemorrhage: causes, CT findings, and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 193:1077–1087

Federle MP, Pan KT, Pealer KM (2007) CT criteria for differentiating abdominal hemorrhage: anticoagulation or aortic aneurysm rupture? AJR Am J Roentgenol 188:1324–1330

Pretorius ES, Fishman EK, Zinreich SJ (1997) CT of hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant therapy. J Comput Assist Tomogr 21:44–51

Patil N, Krane L, Javed K et al (2009) Evaluating and grading cystographic leakage: correlation with clinical outcomes in patients undergoing robotic prostatectomy. BJU Int 103:1108–1110

Guru KA, Seereiter PJ, Sfakianos JP et al (2007) Is a cystogram necessary after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy? Urol Oncol 25:465–467

Raman JD, Dong S, Levinson A et al (2007) Robotic radical prostatectomy: operative technique, outcomes, and learning curve. JSLS 11:1–7

Williams TR, Longoria OJ, Asselmeier S et al (2008) Incidence and imaging appearance of urethrovesical anastomotic urinary leaks following da Vinci robotic prostatectomy. Abdom Imaging 33:367–370

Hung CF, Yang CK, Cheng CL et al (2011) Bowel complication during robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Anticancer Res 31:3497–3501

Kheterpal E, Bhandari A, Siddiqui S et al (2011) Management of rectal injury during robotic radical prostatectomy. Urology 77:976–979

Tollefson MK, Frank I, Gettman MT (2011) Robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy decreases the incidence and morbidity of surgical site infections. Urology 78:827–831

Carlsson S, Nilsson AE, Schumacher MC et al (2010) Surgery-related complications in 1253 robot-assisted and 485 open retropubic radical prostatectomies at the Karolinska University Hospital, Sweden. Urology 75:1092–1097

Catala V, Sola M, Samaniego J et al (2009) CT findings in urinary diversion after radical cystectomy: postsurgical anatomy and complications. Radiographics 29:461–476

Orvieto MA, Coelho RF, Chauhan S et al (2011) Incidence of lymphoceles after robot-assisted pelvic lymph node dissection. BJU Int 108:1185–1190

Kang DI, Woo SH, Lee DH et al (2012) Incidence of port-site hernias after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy with the fascial closure of only the midline 12-mm port site. J Endourol 26:848–851

Spaliviero M, Samara EN, Oguejiofor IK et al (2009) Trocar site spigelian-type hernia after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Urology 73(1423):e1423–1425

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this work.

Note of thanks

We would like to thank our professional nurses Nerea Bevilacqua, Nadia Cortesi, Eugenia Ferron, and Giacomo Nocera for their valuable help in developing and performing the MDCT urography and MDCT cystography techniques, as well as for their daily care of patients in the radiology department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tonolini, M., Villa, F. & Bianco, R. Multidetector CT imaging of post-robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy complications. Insights Imaging 4, 711–721 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0280-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0280-6