Abstract

Digital media is currently one of the defining topics in discussions about schools and teaching. In this context, there has been a wide range of research in physical education (PE) in areas such as health, gamification, and wearable technologies. This raises the question of the goals pursued by empirical studies regarding the use of digital media in PE. The present systematic review provides an overview of the state of research in English and German on the use of digital media in PE. To this end, the included studies were those published between 2009 and 2020 in journals or edited volumes or as dissertations. They were found in relevant databases, selected based on criterion-guided screening, and transferred to the synthesis. Overall, this systematic review presents the possibilities and limitations of digital media in PE and highlights the goals regarding the use of digital media in PE that are pursued by empirical studies in the categories of physical, cognitive, social, affective, and school framework conditions. While benefits from the usage of digital media in PE—such as in terms of motivation or improving sport-specific motor capabilities and skills—were identified, barriers regarding the preparation of PE teachers were also found. More specifically, the benefits of using digital media to achieve PE-related goals were in the foreground in many of the selected studies. However, only a few specifically addressed learning via media, including topics such as data protection and the effect that viewing images has on students’ self-concepts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and theoretical background

Digital media permeates the everyday lives of children and youth. The various technologies may change, but their general interpretation follows a similar pattern with many positive attributes including educational innovations or even revolutions (Kerres, 2022). However, digital media is associated with opportunities and risks, such as insufficient physical activity or addiction (Kerres, 2022). Since these can hardly be completely avoided, they must be dealt with in a pedagogical manner. Moreover, schools are tasked with adequately preparing students for life in present and future society, which now also includes a deeply mediatized world (Couldry & Hepp, 2013). Further, school conditions can be both inhibitory and beneficial (Gerick, Eickelmann, & Labusch, 2018).

In this context, digital media and how it should be dealt with is currently a dominant topic in discourse about schools and teaching. Since it is usually not taught as a separate subject, media education must be included as part of traditional subjects, which can have some advantages, e.g., the consequent increased motivation by the addition of media of students across subjects can be seen (Engen, Giaever, & Mifsud, 2018). While science-oriented research, for example, tend to meet this challenge openly, in discussions regarding physical education (PE), digital technology has mostly been connected to topics such as lack of exercise. Specifically, PE with its special feature as an esthetic subject in terms of physicality, plays a particular part in these discourses. In addition to the original aims such as promoting health and a physically active life or learning sports-specific skills, PE has to now also deal with media education topics (Greve, Thumel, Jastrow, Krieger, & Süßenbach, 2020). However, the varying didactic designs of PE worldwide have further complicated the handling of digital media. While only a few empirical studies on digital media in PE have been published in German-speaking countries in recent years (Greve et al., 2022)Footnote 1, there has been a diversity of research in international publications focusing on topics such as health, gamification, wearable technologies, and cooperative learning with digital media (Casey & Jones, 2011; Goodyear, Casey, & Kirk, 2014). In addition to the emphasis on possibilities and opportunities, there have also been criticisms. While acknowledging digital media as a useful tool in PE, some authors have also noted that it is problematic in this context. More specifically, van Hilvoorde and Koekoek (2018) described the omnipresence of digital technology in our society as capable of undermining the goals of PE in many ways. However, they also listed the completely new possibilities that are a result of new technologies, such as virtual or augmented reality. These allow for new forms of games with new ways of communication, social contacts, and, above all, different and new movement behavior (van Hilvoorde, 2017). However, as some researchers have highlighted, PE teachers are often alone in class. Therefore, it is necessary to plan the use of digital media in a way that is easy to use and geared towards a goal (van Rossum & Morley, 2018). In particular, user behavior (e.g., obstacles when filming bodies and movement and private text messaging) when using personal mobile devices may upset previously accustomed classroom activities (Steinberg, Zühlke, Bindel, & Jenett, 2020). In this context, Casey, Goodyear, and Armour (2017) argued that there is a considerable gap in relation to the connection between digital technology and pedagogy. Pedagogy in this case is considered the connection among ‘learners and their learning’, ‘teachers and their teaching’, and ‘knowledge in context’ (Quennerstedt, Gibbs, Almqvist, Nilsson, & Winther, 2016). These areas can also be found in a similar way in German-language sport pedagogy. On the one hand, the curricula and educational plans provide educational goals and content, while on the other, the student as an individual subject should (and can) only form itself and is in focus. This means that while a teacher can design the learning environment and thus prepare and support the learning process, the completion of the learning process, is dependent on the student acting accordingly as a self-forming individual subject (Gröben & Prohl, 2012; Prohl, 2006). Furthermore, there have also been similar discourses internationally. For example, Kirk (2012) argued that learning should be approached in the physical, cognitive, social and affective domains in a coherent manner so that a physically active life can be promoted. In addition, he identified the aforementioned domains as the legitimate learning outcomes of PE, and thus these will be used as categories when reviewing studies in this paper.

Due to the topicality of this issue and the multitude of aspects described regarding the use of digital media in PE as well as the media pedagogic goals in schools, empirical education research is inevitably faced with the question of which goals regarding the use of digital media in PE can be identified. This is where this review makes its contribution by compiling findings on the possibilities and limitations.

Methods

The aim of this systematic literature review (Davies, 2000; Petticrew & Roberts, 2012) is to examine the material pertaining to a particular area (Shulruf, 2010), while the focus is on the examination of potential methodological biases from the perspective of the researchers (Shulruf, 2010). To undertake a systematic literature review of empirical studies on the use of digital media in PE, Shulruf’s (2010) five methodological steps were applied for data collection and analysis. Specifically, the first four steps were used as criteria for the inclusion or exclusion of a study, while the last step was used to analyze the selected studies. This approach recognizes the existing research and aims to synthesize the results while simultaneously recognizing and considering the researchers’ biases (Barr, Hammick, Koppel, & Reeves, 1999; Boaz, Ashby, & Young, 2002). Here, it should be noted that the focus of a systematic literature review should be on a specific question, which is as follows for this study: Which goals are pursued by empirical studies regarding the use of digital media in PE? To answer this question, it was subdivided into three research questions:

-

Which media usage is empirically verified?

-

To what extent has the intended goal been empirically achieved?

-

What barriers to the use of digital media can be derived from the research?

Moreover, the basis of this study is an examination of specialist journals, edited volumes, and dissertations that deal with the use of digital media in PE specifically. Overall, the literature reviewed in this article includes empirical studies from 2009–2020 that cover primary, secondary, and special-needs schools.

Research

To identify as much relevant literature as possible (Shulruf, 2010), we searched the ERIC, FIS, Web of Science, and PubPsych databases as well as the BISp research system using the following terms: regarding digital media and technologies, we used the terms ‘mobile’, ‘digital’, ‘smartphone’, ‘handy’, ‘tablet’, ‘iPad’, ‘android’, ‘software’, ‘notebook’, ‘laptop’, ‘computer’, ‘handheld’, ‘gaming’, ‘exergames’, ‘video’, ‘technolog*’, ‘media’, ‘medien’, ‘virtual’, and ‘augmented’. However, for the PubPsych database, we had to separate the search term after ‘video’ and divide the search into two parts because the input field in the database was not large enough to search for all the terms at once. Meanwhile, for PE, we used the terms ‘physical education’ and ‘Sportunterricht’ to avoid hits from other sport settings. The last search run in the main search took place on June 30, 2020.

Table 1 shows the total number of articles found using the aforementioned process in the first search run in all databases. In the second step, duplicates were removed using the reference management program Citavi.

Selection of studies

The decision to include or exclude studies was made on the basis of methodological criteria (Shulruf, 2010). The abstracts of the articles found were reviewed according to the following criteria and, if found suitable, selected for further processing:

-

Empirical studies dealing with the topic of digital media and technologies in PE were included.

-

Studies in which the research subjects were actors in PE were included.

-

Studies in which the methodical procedure of the study was clearly and comprehensibly described were included.

-

Approaches and concepts for practical implementation and studies dealing with the development of measuring instruments were excluded.

-

Studies published in journals and edited volumes as well as dissertations were included. However, abstract volumes were excluded due to their low information content.

-

Predatory journals were excluded.

-

Articles written in German or English were included.

The 3355 titles and abstracts from the research in the databases were screened using Abstrackr software to verify that they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Newman & Gough, 2019). This step was independently undertaken by five researchers, with each title randomly assigned and screened twice by two different people. The resulting conflicts were reconsidered and finally assessed by a third person. After this assessment, 135 titles remained.

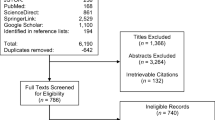

Each of these 135 studies was read to confirm or reject its inclusion in the review by assessing all of the aforementioned criteria. Afterwards, the studies were coded to facilitate the task of analysis by sifting through relevant material (Potter, 2009). The texts were given preliminary notes about their nature, research focus, and results, allowing us to filter all (or a subset of) data on a particular topic (Lee & Fielding, 2009). Next, we compared the individual codes and contents of the table and either combined and classified them into subcategories or discarded them. In order to avoid biases and increase the reliability of the results, all important decisions were jointly made by the research team (Kitchenham, 2004). Following this procedure, we first included 71 studies in the review. Next, in a second, methodologically identical search in August 2021, studies from July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020 were added (Fig. 1). Due to the limited search options in some databases, the search was conducted for the entirety of 2020. Table 2 shows the search hits from each database.

The hits were again sorted according to the above criteria after reading the titles and abstracts. In the end, 79 studies remained and were subjected to a full-text analysis. The full-text analysis and sorting of studies from the first half of 2020 resulted in seven remaining studies, which were integrated into the review. Thus, a total of 78 studies were finally included.

Risk of bias

Relevant information was extracted from the publications and presented descriptively (Bem, 1995; Döring & Bortz, 2016). Here, the risk of bias was not an exclusion criterion, as this would have resulted in a significant reduction in the number of eligible studies. In addition, with such an exclusion, we would have had to abandon the goal of providing an overview of research on digital media in PE. To ensure the quality of the eligible studies, the authors independently checked compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the individual studies.

Results

As not all studies could be described fully in this article, the important information from the studies is summarized in Table 3. The studies identified for the systematic review examined the goals and effects of digital media in PE and were designed very differently. To this end, they examined both teachers and students. The number of people surveyed ranged from 2 to 1421, which also shows the considerable heterogeneity in the study designs. The types of schools examined were elementary, secondary, and special-needs. More specifically, primary schools are described in this context up to grade 6 and secondary schools as grade 7 and above. Moreover, the studies were assigned to different categories: (1) physical, (2) cognitive, (3) social, (4) affective, and (5) school conditions. The aforementioned categories were derived from the key learning outcomes of pupils according to Kirk (2012) and supplemented by those of school conditions (Gerick et al., 2018). The subcategories were inductively derived from the studies, in which different types of media and digital artefacts were used for PE. These revealed various possibilities and limitations, depending on the subject of investigation, and are explained in the following section in order to focus on the result categories.

Digital videography was addressed in 18 of the studies. One usage type was a form of video self-modelling (Casey & Jones, 2011; O’Loughlin et al., 2013), which Dowrick (2012) described as ‘a form of observational learning with the distinction that the observed and the observer, object, and subject, are the same person’. This allows for a form of teacher-independent video feedback, which Kok et al. (2020) examined in comparison to that which was dependent. In addition to providing feedback, it can also serve as an option for assessment or assessment support (Casey & Jones, 2011; O’Loughlin et al., 2013; Weir & Connor, 2009). Furthermore, another aspect when dealing with digital videography is the improvement of motor or cognitive performance, which has been investigated in many studies, as described below in the results.

Meanwhile, the use of exergames in PE was investigated in 25 studies. In those classrooms, the Nintendo Wii (Nintendo K.K., Kyōto, Japan) or X‑Box Kinect (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) were used with various sport games, such as Wii Sports and Kinect Ultimate Sports or other similar games. A large number of the studies focused on the Dance Dance Revolution or other dance-based games (Andrade et al., 2019; Burges Watson et al., 2016; Chen & Sun, 2017; Fogel et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017; Gibbs et al., 2017; Lwin & Malik, 2012; Quintas et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2018; Rincker & Misner, 2017; Sun, 2012; Ye et al., 2018). Thus, studies on using exergames in PE mainly focused on increasing physical activity or involving students in the classroom (Casey & Jones, 2011; Goodyear et al., 2014) while maintaining motivation and joy. Furthermore, heart rate monitors and pedometers were another tool widely used in the studies. They were used to record fitness-specific data and frequently in addition to exergames to record physical activity (Gao et al., 2017; Lee & Gao, 2020; Ye et al., 2018).

In addition to the options just mentioned, there were numerous apps that were used for applied research in the classroom, such as those in fitness for recording data (Cheng & Chen, 2018), those for video evaluations and tagging movements or game situations such as Coach’s Eye (Koekoek et al., 2019; Kok et al., 2020), and those for creating media products (Greve et al., 2022; Steinberg et al., 2020). In addition, two studies worked with wikis to enable students to also collaboratively learn outside the sport hall (André & Hastie, 2018; Hastie et al., 2010), thus, opening up the boundaries of PE.

Physical

The studies from the first category examined the relationship between the use of digital media in PE and physical activity as well as the effects on motor skills or the fitness of students. We identified 30 studies that could be categorized under this topic, which are further described below.

Physical activity

Seventeen studies examined the relationship between physical activity and digital media. Twelve studies were conducted in primary schools (Fogel et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017; Hansen & Sanders, 2010; Lee, 2018; Lee & Gao, 2020; Reynolds et al., 2018; Shewmake et al., 2015; Sun, 2012, 2013; Wadsworth et al., 2014) and six in secondary schools (Huang & Gao, 2013; Lonsdale et al., 2017; Lwin & Malik, 2012; Nation-Grainger, 2017; Zhu & Dragon, 2016)Footnote 2. Three studies examined this relationship qualitatively via interviews or field notes (Engen et al., 2018; Hansen & Sanders, 2010; Sargent & Casey, 2019), while 13 examined physical activity quantitatively with, for example, the help of heart rate monitors, step counters, or questionnaires (Zhu & Dragon, 2016; Sun, 2012, 2013; Lee & Gao, 2020; Lwin & Malik, 2012; Lonsdale et al., 2017; Wadsworth et al., 2014; Fogel et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017; Shewmake et al., 2015; Huang & Gao, 2013; Lee, 2018; Reynolds et al., 2018). Finally, one study was based on a mixed-methods design (Nation-Grainger, 2017).

In addition to the highly heterogeneous research methods, a variety of results and a mixed picture between possibilities and limitations emerged. In the following section, studies involving low physical activity are presented first. Specifically, various studies examined the effects of the use of mobile apps on physical activity in primary school PE and found that it was not effective in improving physical activity and psychosocial beliefs in elementary school children in the short term (Lee, 2018; Reynolds et al., 2018). In some studies, sedentary behavior increased when using digital media and light exercise behavior decreased (Gao et al., 2017; Lee, 2018; Lee & Gao, 2020). In contrast, light physical activity increased in comparison classes without digital media (Lee & Gao, 2020). Unlike light movement, intensive movement increased in these studies (Gao et al., 2017; Lee, 2018). In this context, Zhu and Dragon (2016) showed that there was only a small influence on the increase in physical activity. Further, Huang and Gao (2013) were also unable to detect any increase in physical activity when using an exer-dance game.

Meanwhile, Wadsworth et al. (2014) found that the group playing adapted tennis without digital media took a significantly higher number of steps as compared to those in an exergame. According to the self-assessment of primary school students, they liked the lessons with exergames better but also felt that they were moving less than usual (Shewmake et al., 2015). Additionally, Sun (2012) showed that an exergaming unit in a primary school did not meet the criteria for moderate physical activity unlike the fitness unit that was used as a comparison.

In contrast, a follow-up study in a secondary school, in which exergaming was compared to traditional PE classes, found that the children exercised more during the exergaming unit (Sun, 2013). Some studies have confirmed this possibility and recorded an increase in light to heavy physical activity (Fogel et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017; Lonsdale et al., 2017; Lwin & Malik, 2012). Further, the results of the qualitative study by Hansen and Sanders (2010) showed that active play in PE can be used to increase the physical activity levels of children. The students who actively played during PE class demonstrated a determination to play and a voluntary desire to engage in and persist with technology-enhanced physical activity. The case study by Sargent and Casey (2019) showed that from the teachers’ perspective, flipped learning (FL) in conjunction with digital media optimized teaching time and allowed for more activity.

Finally, when comparing the studies that took place in primary schools with those from secondary schools, slight tendencies became apparent. The former generally found that physical activity could not be improved or was even negatively influenced, while the latter mostly showed a positive development in physical activity. However, the number of studies was too small to allow for conclusions to be drawn.

Improvement of sport-specific motor capabilities and skills

Ten studies described the relationship between the use of digital media and the improvement of motor capabilities. Two were conducted in primary schools (Rincker & Misner, 2017; Sheehan & Katz, 2012) and eight in secondary schools (Chang et al., 2020; Kok et al., 2020; Kretschmann, 2017; Nowels & Hewit, 2018; Palao et al., 2015; Potdevin et al., 2018; Rekik et al., 2019; Sohnsmeyer, 2011). Six studies examined the improvement of motor capabilities and skills quantitatively, and four were based on a mixed-methods design. However, qualitative studies on this topic were not found.

More specifically, two of these studies described no difference between the test and comparison groups, and therefore found no significant improvement or deterioration in motor capabilities and skills through the use of digital media (Kok et al., 2020; Rincker & Misner, 2017). However, another study showed that the group that used exergames in PE achieved just as significant an improvement in terms of the capability of balancing as the group that used a specific fitness program, while the control group did not achieve this in normal PE (Sheehan & Katz, 2012). Meanwhile, in secondary schools, an improvement in specific capabilities could also be demonstrated through the use of exergames. In three studies, Sohnsmeyer (2011) showed that dealing with high-movement table tennis increased game-specific responsiveness.

In addition to exergaming, we found several studies that focused on the help of video feedback. A quantitative study found a significant improvement in motor skills when a gymnastics exercise was learned with the help of video feedback (Potdevin et al., 2018). Nowels and Hewit (2018) were also able to show improvement in the learning of motor skills through video feedback combined with verbal feedback. Further, Palao et al. (2015) used a mixed-methods design to compare teachers’ verbal feedback, video and teacher feedback, and video and student feedback. They found that video and teacher feedback delivers the most positive overall results and significant improvements in motor skills. Rekik et al. (2019) examined the effects of different teaching media (videos and images) for basketball. Learning with dynamic videos provided more of an improvement in game performance as compared to that with normal images. Chang et al. (2020) took this further by examining the difference between video feedback with normal videos and augmented reality. First, the two groups’ running were rated by teachers. Here, the experimental group received significantly better ratings for their running style. Overall, the aforementioned studies confirm that using digital media in PE results in an improvement in motoric capabilities and skills.

Physical condition

Six studies examined physical fitness and how it has changed through the use of digital media in PE, with the aim of improving body-related performance parameters. Four of these studies were carried out in primary schools (Bendiksen et al., 2014; Chen & Sun, 2017; Cheng & Chen, 2018; Nation-Grainger, 2017; Rincker & Misner, 2017; Ye et al., 2018). Except for Bendiksen et al. (2014), all studies in this subcategory indicated the possibility of increasing the fitness of students with the help of digital media. Specifically, in an intervention study, Ye et al. (2018) showed that PE classes combined with exergaming had a positive effect on students’ BMI and fitness. Further, in their comparative study, Cheng and Chen (2018) also showed that the traditional PE classes that recorded fitness data with the help of apps led to a greater increase in fitness values than those without apps. Chen and Sun (2017) demonstrated that a 6-week program of active videogames was an effective strategy to improve children’s cardiorespiratory fitness while maintaining the joy of PE. Finally, using a 6-week intervention study at a secondary school, Nation-Grainger (2017) was able to show that the use of heart rate monitors on the wrists of those in the test group and the resultant individual feedback increased both calories burned and distance run.

In sum, all studies that examined the association between the use of digital media and physical fitness of students showed positive results. However, it should be noted that digital media should not be used to acquire physical fitness without considering and addressing the related data protection issues. Thus, its use for this purpose should be well planned.

Cognitive

Twelve studies examined students’ increase in knowledge when dealing with digital media. In other words, their main focus was learning with and through media. The objectives in these studies were to increase knowledge of health issues as well as tactics and play and take care of obesity issues. However, a few studies included learning about media using topics such as data security. Four studies were conducted in elementary schools (Lindberg et al., 2016; O’Loughlin et al., 2013; Quintas et al., 2020) and nine studies in secondary schools (Casey & Jones, 2011; Chen et al., 2016; Gibbs et al., 2017; Jarraya et al., 2019; Østerlie & Mehus, 2020; Palao et al., 2015; Rekik et al., 2019; Weir & Connor, 2009).

In some studies, digital media was used to counteract obesity either by creating motivating movement possibilities for students or by imparting knowledge about health-related aspects. Specifically, in terms of conveying health aspects, digital media played a major role. Chen et al. (2016) showed that a test group with digital step counters on their wrists, which supported learning, understood more about energy balance (the balance between calories consumed and burned) than the comparison group. Here, the step counters allowed for a more precise determination of the calories being burned. Meanwhile, the study by Østerlie and Mehus (2020) showed that the use of FL, consisting of an online video and a separate plan for the lesson, led to more cognitive learning, which in turn led to students having higher levels of health-related fitness knowledge (HRFK).

Besides health issues, some studies have dealt with knowledge of tactics and play. Specifically, Quintas et al. (2020) showed the positive effects of exergaming on basic psychological needs, some flow dimensions, and academic performance. Further, Sohnsmeyer (2011) used three studies on a high-movement table tennis game to show that both game-specific responsiveness and action knowledge could be improved.

Moreover, the use of video feedback led to improved articulation and a deeper understanding of throwing and catching skills (Casey & Jones, 2011). Palao et al. (2015) also showed that video feedback in connection with that from teachers provided a greater increase in knowledge than teacher feedback on its own. Thus, video feedback resulted in a significant improvement in terms of knowledge gained.

Video examples play an important role in acquiring game- or sport-related knowledge, as learning with dynamic videos has been shown to outperform that with static photos in terms of both game understanding and performance (Rekik et al., 2019). The results further indicate less cognitive stress and an improved attitude towards working with videos instead of photos. When using video examples, Jarraya et al. (2019) examined, among other things, the connection between the playback speed of the videos and learning efficiency. There were no significant differences between low- and normal-speed presentation when the complexity of the content was low. However, for content with medium and high complexity, learning with a slow presentation speed was more efficient than that with a normal presentation speed (Jarraya et al., 2019).

In addition to learning with media, a few studies have also addressed learning about media (Greve et al., 2022), and their focus was mainly on learning about the medium being used (Maivorsdotter & Quennerstedt, 2019; Marttinen et al., 2019; Weir & Connor, 2009). While Weir and Connor (2009) mainly perceived the advantages of digital media in subject-related learning with media when using video feedback in secondary schools, they also showed that students felt more confident in dealing with digital media after using video feedback. In addition, some studies went beyond discussing the direct use of the medium but also explored media educational content, such as film language or cinematic means (Goodyear et al., 2014; Greve et al., 2022).

Further, we also identified studies that showed various ways of expanding or influencing the teaching–learning process. Specifically, the forms of cooperative learning in PE expanded through the use of digital media and could be positively influenced (Ma et al., 2018). Wikis, for instance, offered the possibility of maintaining cooperation in extended practice groups and independently of PE classes (Hastie et al., 2010). In addition, new roles (Goodyear et al., 2014; Greve et al., 2022) gave rise to new forms of consultation and cooperation during PE classes, which succeeded in improving student engagement. For example, some students only participated if the task related to social interaction (Goodyear et al., 2014) or were only ready to work with their peers due to the digital medium (Finco et al., 2015). However, the number of such studies was too small and addressed different topics and thus did not allow for the comparison or drawing of conclusions.

Social

Eleven studies described the use of digital media as a good way to enable students to participate in PE, encourage students who would otherwise not take part to do so, and make PE and its content more attractive for students. Five studies took a quantitative approach (Asogwa et al., 2020; Fernández Basadre et al., 2015; Fernández-Batanero et al., 2019; Fogel et al., 2010; Trabelsi et al., 2020), while the remaining used qualitative (Burges Watson et al., 2016; Engen et al., 2018; Finco et al., 2015; Goodyear et al., 2014; Greve et al., 2022) or mixed methods (Casey & Jones, 2011). For instance, Casey and Jones (2011) described how marginalized students benefited the most from video feedback because it made them feel involved, while Asogwa et al. (2020) showed that the use of digital media could increase the engagement of hearing-impaired students. Meanwhile, the results of two other studies suggested that new roles, such as being the cameraperson, were crucial for student engagement (Goodyear et al., 2014; Greve et al., 2022). For example, some girls only participated fully in class if the learning content remained within the social and cognitive dimension; in other words, if they could hide behind the camera and did not have to physically participate (Goodyear et al., 2014). Furthermore, Trabelsi et al. (2020) also found an improvement in engagement among female students. Fogel et al. (2010) confirmed that exergaming is a good method to help inactive children be more physically active, and this included PE as well. Meanwhile, Burges Watson et al. (2016) showed that the use of dance mats had no effect on physical activity but in some scenarios ensured that students who were otherwise difficult to reach could be included. Finco et al. (2015) showed that students who were normally unmotivated in PE had a positive attitude towards exergame practices and were willing to work with other children. Finally, Engen et al. (2018) also described this in their study as a positive side effect in PE.

Affective

This category contains subcategories such as motivation or attitudes caused by the use of digital media in PE.

Motivation and situational interest

Besides physical activity, motivation, and situational interest were among the most researched topics in terms of digital media in PE. The concept of situational interest relates to specific actions led by interest and is described as a unique situation-specific motivational state (Krapp, 1995). Therefore, it is relevant to the study of active involvement. Specifically, 21 studies could be categorized under this topic. Eight studies were carried out in primary schools (Hansen & Sanders, 2010; Lindberg et al., 2016; Marttinen et al., 2019; Quintas et al., 2020; Quintas-Hijós et al., 2020; Sun, 2012, 2013; Papastergiou et al., 2020) and 13 in secondary schools (Chang et al., 2020; Huang & Gao, 2013; Legrain et al., 2015; Østerlie & Kjelaas, 2019; Marttinen et al., 2019; Nation-Grainger, 2017; Østerlie & Mehus, 2020; Potdevin et al., 2018; Roure et al., 2019; Zhu & Dragon, 2016; Marin-Marin et al., 2020; Vega-Ramirez et al., 2020; Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2020). Specifically, five studies examined qualitatively—through, for example, interviews or field notes—while nine examined physical activity quantitatively and five were based on a mixed-methods design. Overall, the majority of studies reported increasing situational interest or motivation through the use of digital media.

As early as 2009, as a main finding of their study, Weir and Connor noted that the use of digital media was suitable for maintaining student engagement. Further, in their qualitative study in secondary schools, Marttinen et al. (2019) confirmed that the use of digital media was a motivating factor for students to increase their physical activity. Marin-Marin et al. (2020) also found a significant difference and thus an improvement in the motivational domain. In addition, in their study, Moreno-Guerrero et al. (2020) were also able to name the biggest difference in the motivational areas for students.

In their qualitative study, O’Loughlin et al. (2013) showed that self-evaluation, self-assessment, and self-regulatory learning through digital videography led to increased motivation. Legrain et al. (2015) and Vega-Ramirez et al. (2020) also found increased self-determined motivation in PE. In their study at a secondary school, Potdevin et al. (2018) showed that the use of video feedback significantly reduced demotivation between the first and fifth hour. Furthermore, other studies have demonstrated the crucial role of teachers when using video feedback in PE classes in terms of improving the situational interest of students. They found that this interest of the group when there was a teacher and video feedback was significantly higher than in groups with only one of the two (Roure et al., 2019). In addition, Østerlie and Mehus (2020) also showed a decrease in motivation among male students if no additional explanation was provided by a teacher.

The connection between exergames and motivation has also been examined in many studies. Quintas-Hijós et al. (2020) found that gamification by means of exergames increased motivation from the students’ perspective. In their study on active video games in PE, Hansen and Sanders (2010) emphasized the above finding and perceived a determination to play as well as the voluntary desire to participate in physical activities and to persist with them. Sun (2012) examined students’ motivation in a fitness unit that was run using exergames, finding that while situational interest decreased over time, it was consistently higher than in the fitness unit without exergames. Further, in their study using a previously developed game, Lindberg et al. (2016) also confirmed that the motivation in the group with exergames was very high. A decrease in motivation over time in both groups was also shown by Sun (2013) in her quantitative study on the use of exergames in a secondary school.

Chang et al. (2020) examined the effect of augmented reality on learning motivation during a lesson about running and found that the experimental group achieved significantly higher levels of learning motivation than the comparison group. Meanwhile, Zhu and Dragon (2016) examined physical activity as well as the motivation to move. Their results point to less situational interest in the test group with digital media than in the comparison group. However, Nation-Grainger (2017) found no differences in motivation when comparing a group of students using heart rate monitors on their wrists with one without such devices. In their study using a dance simulation in PE, Huang and Gao (2013) also detected only moderate situational motivation.

Overall, many studies have indicated that motivation and situational interest in PE can be increased for a short period of time. In the long term, however, there are indications that situational interest declines over time (Sun, 2012, 2013). This may be due to the digital medium used or to its novelty in PE. Further, even though there have been studies and research on this subject for over 10 years, its use in everyday life at schools is still rare in PE. It has also been shown that situational interest strongly depends on additional interactions with teachers (Østerlie & Mehus, 2020; Roure et al., 2019).

Enjoyment

In conjunction with gamification and exergames in particular, the connection between the use of digital media and enjoyment was examined in five studies. Apart from one mixed-methods study (Quintas-Hijós et al., 2020), only quantitative studies have been used to deal with this topic (Andrade et al., 2019; Kok et al., 2020; Shewmake et al., 2015). Here, various questionnaires and scales, such as the Brunel Mood Scale, were used for this purpose.

Specifically, Andrade et al. (2019) showed that the use of exergames improved the class atmosphere during lessons. Quintas-Hijós et al. (2020) found that a lesson with exergames could be an effective strategy to improve cardiorespiratory fitness in children while maintaining the enjoyment of physical activity. Here, the gamification method generated more enthusiasm, while the exergame itself made motor learning more fun (Quintas-Hijós et al., 2020). Shewmake et al. (2015) examined the degree of perceived enjoyment in elementary schools with and without the use of exergames and found that the students liked the former to a significantly greater extent. However, in their study on self-controlled video feedback during shotput, Kok et al. (2020) were unable to show any difference in perceived enjoyment.

Attitudes and self-efficacy

The studies in this subcategory examined the relationship between the use of digital media and changes in self-efficacy and attitudes towards PE topics. They found that the use of digital media can significantly influence students’ attitudes towards physical activity. For example, participants in exergames-based PE tended to develop positive behavior and attitudes as well as a better understanding of their perceived learning progress (Koekoek et al., 2019; Lwin & Malik, 2012). Further, the use of exergames had a greater influence on younger students than older ones. Attitudes were also more positively influenced with the help of audio augmentation. Relaxation and expression were positively influenced as were social interaction and perceived competence. However, in the event of failure, there was negative reinforcement (Ma et al., 2018). Meanwhile, Kok et al. (2020) examined self-efficacy in dealing with digital media—more precisely with video feedback. Their main finding was that video feedback only improves students’ self-efficacy if the video feedback is controlled by the student and not others (Kok et al., 2020). Penney et al. (2012) were able to show that the use of digital media and the digital recording of student results, in particular, in the form of video recordings, for example, was perceived by students as authentic and meaningful.

School conditions

The studies in this subcategory examined the conditions in school when digital media was used in PE. Most of the studies had teachers as a sample. Their results indicated that teachers tended to have positive attitudes towards digital media (Gibbone et al., 2010; Legrain et al., 2015; Tou et al., 2020). However, there were differences regarding age, experience and gender: for example, women used digital media more often than men (Bisgin, 2014; Rojo-Ramos et al., 2020).

More specifically, Penney et al. (2012) showed that teachers perceived the use of digital media as a valid means of assessing the capabilities, knowledge, and understanding of students. Quintas-Hijós et al. (2020) found that teachers viewed exergames as a good opportunity to increase students’ motivation. In addition to direct forms of feedback using digital media—for example, digital videography—Gibbs et al. (2017) found that digital media also provided more time and consequently gave teachers the opportunity to give feedback, among other things.

This category also includes studies that show limitations and challenges on a structural level, thus, making barriers to the use of digital media clear. This includes, for example, a high time requirement or lack of training. A total of 13 studies presented results on this topic: six were quantitative in nature (Aktag, 2015; Bisgin, 2014; Fernández-Batanero et al., 2019; Hill & Valdez-Garcia, 2020; Legrain et al., 2015; Rojo-Ramos et al., 2020), four adopted a qualitative approach (Baek et al., 2018; Marttinen et al., 2019, 2020; Steinberg et al., 2020), and two used a mixed-methods design (Kretschmann, 2015; Robinson & Randall, 2017).

They found that the lack of resources was often a major reason for not including digital media in PE. Specifically, regarding barriers influencing the use of digital media, teachers named class size as well as lack of access to media, support, time, expertise, and budget (Hill & Valdez-Garcia, 2020; Legrain et al., 2015; Robinson & Randall, 2017). The given resources also influenced the way in which digital media were used in the classroom (Marttinen et al., 2020).

Moreover, in a survey, teachers did not consider themselves well prepared for the use of digital media in PE and believed that specific training was necessary for their use (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2019). Besides the lack of training, teachers stated that they used digital media less (Baek et al., 2018; Legrain et al., 2015) because they had never experienced digital media in their own lessons as students (Baek et al., 2018). In addition, there were differences in terms of gender and age. Women used digital media more often in PE and felt better prepared for its use than their male colleagues. Further, the older the teachers were, the less that technology was used (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2019; Hill & Valdez-Garcia, 2020; Rojo-Ramoz et al., 2020). Finally, knowledge of the medium used also played a role in the studies. For example, the better the computer skills of sport teachers, the likelier it was that they also used them in PE (Kretschmann, 2015; Rojo-Ramoz et al., 2020) and the lesser the anxiety before use (Aktag, 2015).

Discussion

This review presents the goals pursued by empirical studies regarding the use of digital media in PE as well as the current state of research on the possibilities and limitations of this use. We found that the studies use different technologies that have changed over time and will continue to change. It also became clear that a research focus is needed that not only refers to software and hardware but also takes a didactic perspective. This is reflected in PE as described by Kerres (2022) for studies in the area of digital media in schools.

In addition to the understanding of the digital medium and its influence, the understanding of PE influences the use of digital media, and the studies reveal very different understandings of PE. There are some at the international level that are similar to that of the German discourse (Prohl, 2006; Kirk, 2012, 2013), but most studies focus on the physical condition and activity and the functional use of digital media. The emphasis on these areas in the literature could possibly be explained by experience in the use of digital media in professional sports. Video feedback, for example, has been used for a long time in the club sport settings. Due to traditional understandings of PE, this practice has often been introduced into schools, especially PE. Further, this feedback can be a great way to improve sport-specific capabilities and skills. When using it, however, the teacher must consider that seeing oneself can have an impact on one’s self-image. Nevertheless, only a few studies paid attention to these effects, and they found that students had the desire to look good in the videos (Casey & Jones, 2011; Greve et al., 2022) and that hierarchies of desirable bodies were unconsciously produced by the teachers (van Doodewaard, Knoppers, & van Hilvoorde, 2018). Thus, these effects, which can play a role unrelated to the improvement of performance, must be reflected on by teachers when using digital media. Meanwhile, mutual filming and its associated new roles and tasks offer the opportunity to make more students enthusiastic about sport-specific topics. In this context, the functional use of digital media to achieve the goals of PE—learning with media—was the focus of a large number of the studies. However, only a few studies showed a specific interest in learning about media as well, addressing questions of data protection, legal aspects, or other media education topics. In interventions with digital media, including those not involving PE, students did not seem concerned about issues such as data protection related to the use of smartwatches (Engen et al., 2018). At this point, the opportunities for children to learn something about media were often not used by setting goals related to digital media use in PE. This is often based on the expectation that digital media is to be used as a tool to increase performance and activity.

As Marttinen et al. (2019) reported, the use of digital media for teaching and learning still has a long way to go. While digital media as a tool for use in PE is becoming more widespread, the didactic perspective has remained less illuminated in the empirical context. This is where the gap between the use of technology in PE and the didactics behind it becomes visible. On the one hand, curricula specify objectives and content in relation to digital media, while on the other, the pupil at the center and as an individual subject can only educate themselves. This means that the teacher can design the learning environment with digital media and thus prepare and support the learning process. However, the completion of the learning process depends on the student as a self-forming individual subject acting accordingly (Gröben & Prohl, 2012; Prohl, 2006). Here, the advantage of digital media is that it plays a major role in the everyday world of the students and thus, as can be seen in this review, increases the motivation for the self-educational process among students. In this way, the use of digital media influences the educational and didactic goals of PE. In addition, the possibilities of using digital media to adapt learning materials and content in PE to enable students to learn were made clear in this review. Despite this focus on physical activity and the mixed results in this regard, it is worthwhile to use digital media to integrate students who would otherwise not participate at all into classes (Goodyear et al., 2014) or to enhance learning through self-assessment and self-regulatory learning (O’Loughlin et al., 2013). Additionally, digital media can also create a connection between the media world inside and outside of school and were often used successfully as motivational aids to increase activity, motivation, and enjoyment. However, when using exergames in PE, for example, there is a high level of effort in terms of preparation and high costs in the purchase of equipment, which is certainly a limiting factor for its implementation in PE. In this context, students also mentioned the bulkiness of the devices and the lack of their accessibility at home as problems (Marttinen et al., 2019).

Limitations

For this overview of the research results on the use of digital media in PE, certain inclusion and exclusion criteria were used, which formed an important condition for the development of this systematic review. Since certain search terms were required for this process, it is conceivable that important studies that did not include any of the above-mentioned search terms in their titles, abstracts, or keywords were not included in the systematic review. Furthermore, this review only included English and German texts and excluded, for example, the large number of studies that have been published in Spanish. However, country-specific peculiarities in the education systems, and especially in the perceptions of PE, limit the transferability of individual study results across national borders.

Here, it should also be noted that the authors from the working group of this systematic review were involved in one of the listed studies.

Conclusion

While there are benefits of using digital media in physical education (PE)—for example, in motivating or improving sport-specific motor capabilities and skills—barriers in terms of the preparation of PE teachers was demonstrated in this review. Thus, for its successful use, teachers need better training and preparation, since the effect of digital media in PE depends largely on presentation in an appropriate form and additional instructions given by the teacher (Østerlie & Mehus, 2020; Roure et al., 2019). The main focus should consequently be on preparation and training in terms of didactic, methodological, and media educational content, as the tools being used will continue to change over time. In addition, the studies reviewed also emphasized that teachers need to use digital media to focus on thinking critically about media content (De Araújo, Knijnik, & Ovens, 2020) and that they need to be provided with a reflexive approach to the use of digital media (Bodsworth & Goodyear, 2017). The understanding of PE also strongly affects how and why digital media are used in PE: Is PE about performance in the sense of sport-specific skills, or is it also about learning beyond them? For these reasons, preservice teachers should already be trained during their studies to use digital media in ways that go beyond performance-oriented goals in PE. Moreover, the focus of the examined research reflects the understandings of PE. Most studies were centered on improving physical performance or activity and rarely went beyond this. Thus, additional insights into students’ experiences with and learning about media in PE have not yet been considered. In this context, learning with and about media as well as about the influence of digital technologies on the body and one’s own sporting activities must be addressed in research and school in order to meet the demands of school.

Notes

The article was published online in 2020 and is therefore included in the review.

Because of studies that took place in both elementary and secondary schools, there may have been double counting.

References

Aktag, I. (2015). Computer self-efficacy, computer anxiety, performance and personal outcomes of Turkish physical education teachers. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(3), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2014.2016.

Andrade, A., Correia, C. K., d. Cruz, W. M., & Bevilacqua, G. G. (2019). Acute effect of exergames on children’s mood states during physical education classes. Games for Health Journal: Research, Development, and Clinical Applications, 8(4), 250–256.

André, M., & Hastie, P. (2018). Comparing teaching approaches in two student-designed games units. European Physical Education Review, 24(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16681955.

Asogwa, U. D., Ofoegbu, T. O., Ogbonna, C. S., Eskay, M., Obiyo, N. O., Nji, G. C., Ngwoke, O. R., Eseadi, C., Agboti, C. I., Uwakwe, C., & Eze, B. C. (2020). Effect of video-guided educational intervention on school engagement of adolescent students with hearing impairment. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020643.

Baek, J.-H., Jones, E., Bulger, S., & Taliaferro, A. (2018). Physical education teacher perceptions of technology-related learning experiences: a qualitative investigation. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0180.

Barr, H., Hammick, M., Koppel, I., & Reeves, S. (1999). Evaluating interprofessional education: two systematic reviews for health and social care. British Educational Research Journal, 25(4), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250408.

Bem, D. J. (1995). Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 118(2), 172–177.

Bendiksen, M., Williams, C. A., Hornstrup, T., Clausen, H., Kloppenborg, J., Shumikhin, D., Brito, J., Horton, J., Barene, S., Jackman, S. R., & Krustrup, P. (2014). Heart rate response and fitness effects of various types of physical education for 8‑ to 9‑year-old schoolchildren. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(8), 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.884168.

Bisgin, H. (2014). Analyzing the attitudes of physical education and sport teachers towards technology. The Anthropologist, 18(3), 761–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891607.

Boaz, A., Ashby, D., & Young, K. (2002). Systematic reviews: What have they got to offer evidence based policy and practice? https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/wp-content/uploads/Should-I-do-a-systematic-review.pdf ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice. Accessed 15.01.2021.

Bodsworth, H., & Goodyear, V. A. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to using digital technologies in the Cooperative Learning model in physical education. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 22(6), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1294672.

Burges Watson, D., Adams, J., Azevedo, L. B., & Haighton, C. (2016). Promoting physical activity with a school-based dance mat exergaming intervention: qualitative findings from a natural experiment. BMC Public Health, 16, 609. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3308-2.

Casey, A., & Jones, B. (2011). Using digital technology to enhance student engagement in physical education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 2(2), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2011.9730351.

Casey, A., Goodyear, V. A., & Armour, K. M. (2017). Rethinking the relationship between pedagogy, technology and learning in health and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(2), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1226792.

Chang, K.-E., Zhang, J., Huang, Y.-S., Liu, T.-C., & Sung, Y.-T. (2020). Applying augmented reality in physical education on motor skills learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(6), 685–697.

Chen, H., & Sun, H. (2017). Effects of active videogame and sports, play, and active recreation for kids physical education on children’s health-related fitness and enjoyment. Games for Health Journal, 6(5), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2017.0001.

Chen, S., Zhu, X., Kim, Y., Welk, G., & Lanningham-Foster, L. (2016). Enhancing energy balance education through physical education and self-monitoring technology. European Physical Education Review, 22(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15588901.

Cheng, C.-H., & Chen, C.-H. (2018). Developing a mobile APP-supported learning system for evaluating health-related physical fitness achievements of students. Mobile Information Systems. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8960968.

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2013). Conceptualizing mediatization: contexts, traditions, arguments. Communication Theory, 23(3), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12019.

Davies, P. (2000). The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and practice. Oxford Review of Education, 26(3/4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688543.

De Araújo, A. C., Knijnik, J., & Ovens, A. P. (2020). How does physical education and health respond to the growing influence in media and digital technologies? An analysis of curriculum in Brazil, Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Curriculum Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1734664.

van Doodewaard, C., Knoppers, A., & van Hilvoorde, I. (2018). ‘Of course I ask the best students to demonstrate’: digital normalizing practices in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 23(8), 786–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1483908.

Döring, N., & Bortz, J. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (5th edn.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41089-5.

Dowrick, P. W. (2012). Self modeling: expanding the theories of learning. Psychology in the Schools, 49(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20613.

Engen, B. K., Giaever, T., & Mifsud, L. (2018). Wearable technologies in the K‑12 classroom—Cross-disciplinary possibilities and privacy pitfalls. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 29(3), 323–341.

Fernández Basadre, R., Herrera-Vidal Núnez, J. I., & Navarro Patón, R. (2015). ICT in physical education from the perspective of students in elementary school. Sportis, 1(2), 141–155.

Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Sañudo, B., Montenegro-Rueda, M., & García-Martínez, I. (2019). Physical education teachers and their ICT training applied to students with disabilities. The case of Spain. Sustainability, 11(9), 2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092559.

Finco, M. D., Reategui, E., Zaro, M. A., Sheehan, D., & Katz, L. (2015). Exergaming as an alternative for students unmotivated to participate in regular physical education classes. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 5(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2015070101.

Fogel, V. A., Miltenberger, R. G., Graves, R., & Koehler, S. (2010). The effects of exergaming on physical activity among inactive children in a physical education classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(4), 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2010.43-591.

Gao, Z., Pope, Z., Lee, J. E., Stodden, D., Roncesvalles, N., Pasco, D., Huang, C. C., & Feng, D. (2017). Impact of exergaming on young children’s school day energy expenditure and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.11.008.

Gerick, J., Eickelmann, B., & Labusch, A. (2018). Schulische Prozesse als Lern- und Lehrbedingungen in den ICILS-2018-Teilnehmerländern. In B. Eickelmann, W. Bos, J. Gerick, F. Goldhammer, H. Schaumburg, K. Schwippert, M. Senkbeil & J. Vahrenhold (Eds.), ICILS 2018 #Deutschland. Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im zweiten internationalen Vergleich und Kompetenzen im Bereich computational thinking (pp. 173–203). Münster. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:18324.

Gibbone, A., Rukavina, P., & Silverman, S. (2010). Technology integration in secondary physical education: teachers’ attitudes and practice. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange. https://doi.org/10.18785/jetde.0301.03.

Gibbs, B., Quennerstedt, M., & Larsson, H. (2017). Teaching dance in physical education using exergames. European Physical Education Review, 23(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16645611.

Goodyear, V. A., Casey, A., & Kirk, D. (2014). Hiding behind the camera: social learning within the Cooperative Learning Model to engage girls in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 19(6), 712–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.707124.

Greve, S., Thumel, M., Jastrow, F., Krieger, C., & Süßenbach, J. (2020). Digitale Medien im Sportunterricht der Grundschule: Ein Update für die Sportdidaktik?! In M. Thumel, R. Kammerl & T. Irion (Eds.), Digitale Bildung im Grundschulalter: Grundsatzfragen zum Primat des Pädagogischen (pp. 325–340). kopaed. Digital media in primary school physical education: an update for sports didactics?!.

Greve, S., Thumel, M., Jastrow, F., Krieger, C., Schwedler, A., & Süßenbach, J. (2022). The use of digital media in primary school PE—Student perspectives on product-oriented ways of lesson staging. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1849597.

Gröben, B., & Prohl, R. (2012). Good practice methods in physical education—Cooperative learning. Journal of Physical Education & Health—Social Perspektie, 1(1), 43–52.

Hansen, L., & Sanders, S. (2010). Fifth grade students’ experiences participating in active gaming in physical education: the persistence to game. ICHPER-SD Journal of Research, 5(2), 33–40.

Hastie, P. A., Casey, A., & Tarter, A.-M. (2010). A case study of wikis and student-designed games in physical education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 19(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759390903579133.

Hill, G. M., & Valdez-Garcia, A. (2020). Perceptions of physical education teachers regarding the use of technology in their classrooms. The Physical Educator, 77(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2020-V77-I1-9148.

van Hilvoorde, I. (2017). Sport and play in a digital world. Ethics and sport. Routledge.

van Hilvoorde, I., & Koekoek, J. (2018). Digital technologies: a challenge for physical education. In C. Scheuer, A. Bund & M. Holzweg (Eds.), Changes in childhood and adolescence: current challenges for physical education: keynotes, invited symposia and selected contributions of the 12th FIEP European Congress (pp. 54–63).

Huang, C., & Gao, Z. (2013). Associations between students’ situational interest, mastery experiences, and physical activity levels in an interactive dance game. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 18(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2012.712703.

Jarraya, M., Rekik, G., Belkhir, Y., Chtourou, H., Nikolaidis, P. T., Rosemann, T., & Knechtle, B. (2019). Which presentation speed is better for learning basketball tactical actions through video modeling examples? The influence of content complexity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02356.

Juditya, S., Suherman, A., Rusdiana, A., Nur, L., Agustan, B., & Zakaria, D.A. (2020). Digital teaching material “POJOK”: One of the technology-based media in physical education learning. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(10), 1774–1784. https://doi.org/10.37200/IJPR/V24I10/PR300204.

Kerres, M. (2022). Bildung in a digital world: the social construction of future in education. In D. Kergel, J. Garsdahl, M. Paulsen & B. Heidkamp-Kergel (Eds.), Bildung in the digital age. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003158851-4.

Kirk, D. (2012). What is the future for physical education in the 21st century? In S. Capel & M. Whitehead (Eds.), Debates in physical education (pp. 220–231). Routledge.

Kirk, D. (2013). Educational value and models-based practice in physical education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45, 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.785352.

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Procedures-for-Performing-Systematic-Reviews-Kitchenham/29890a936639862f45cb9a987dd599dce9759bf5 Software Engineering Group; Empirical Software Engineering. Accessed 24.02.2021.

Koekoek, J., van der Kamp, J., Walinga, W., & van Hilvoorde, I. (2019). Exploring students’ perceptions of video-guided debates in a game-based basketball setting. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(5), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1635107.

Kok, M., Komen, A., van Capelleveen, L., & van der Kamp, J. (2020). The effects of self-controlled video feedback on motor learning and self-efficacy in a physical education setting: an exploratory study on the shot-put. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 25(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1688773.

Krapp, A. (1995). Interesse, Lernen und Leistung. Neue Forschungsansätze in der pädagogischen Psychologie. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 38(5), 747–770. Interest, learning and performance. New research approaches in educational psychology.

Kretschmann, R. (2015). Effect of physical education teachers’ computer literacy on technology use in physical education. The Physical Educator. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2015-V72-I5-4641.

Kretschmann, R. (2017). Employing tablet technology for video feedback in physical education swimming class. Journal of E‑Learning and Knowledge Society. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/143.

Lee, J. E. (2018). Children’s physical activity and psychosocial beliefs in mobile application-based physical education classes. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/194580. Accessed 12.03.2022.

Lee, J. E., & Gao, Z. (2020). Effects of the iPad and mobile application-integrated physical education on children’s physical activity and psychosocial beliefs. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 25(6), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1761953.

Lee, R. M., & Fielding, N. G. (2009). Tools for quantitative data analysis. In M. A. Hardy & A. Bryman (Eds.), Handbook of data analysis. SAGE.

Legrain, P., Gillet, N., Gernigon, C., & Lafreniere, M.-A. (2015). Integration of information and communication technology and pupils’ motivation in a physical education setting. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34(3), 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0013.

Lindberg, R., Seo, J., & Laine, T. H. (2016). Enhancing physical education with exergames and wearable technology. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 9(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2016.2556671.

Lonsdale, C., Lester, A., Katherine, O. B., White, R. L., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). An internet-supported school physical activity intervention in low socioeconomic status communities: results from the Activity and Motivation in Physical Education (AMPED) cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097904.

Lwin, M. O., & Malik, S. (2012). The efficacy of exergames-incorporated physical education lessons in influencing drivers of physical activity: a comparison of children and pre-adolescents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 756–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.013.

Ma, Y., Bekker, T., Ren, X., Hu, J., & Vos, S. (2018). Effects of playful audio augmentation on teenagers’ motivations in cooperative physical play. In The 17th Interaction Design and Children Conference.

Maivorsdotter, N., & Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Exploring gender habits: a practical epistemology analysis of exergaming in school. European Physical Education Review, 25(4), 1176–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18810023.

Marin-Marin, J.-A., Costa, R. S., Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., & Lopez-Belmonte, J. (2020). Makey Makey as an interactive robotic tool for high school students’ learning in multicultural contexts. Education Sciences, 10(9), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090239.

Marttinen, R., Daum, D., Fredrick, R. N., Santiago, J., & Silverman, S. (2019). Students’ perceptions of technology integration during the F.I.T. unit. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 90(2), 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1578328.

Marttinen, R., Landi, D., Fredrick, R. N., & Silverman, S. (2020). Wearable digital technology in PE: advantages, barriers, and teachers’ ideologies. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0240.

Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., Alonso Garcia, S., Ramos Navas-Parejo, M., Campos-Soto, N. M., & Gomez Garcia, G. (2020). Augmented reality as a resource for improving learning in the physical education classroom. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103637.

Nation-Grainger, S. (2017). ‘It’s just PE’ till ‘It felt like a computer game’: using technology to improve motivation in physical education. Research Papers in Education, 32(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1319590.

Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2019). Systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research (pp. 3–22). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1.

Nowels, R. G., & Hewit, J. K. (2018). Improved learning in physical education through immediate video feedback. Strategies, 31(6), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2018.1515677.

O’Loughlin, J., Chróinín, D. N., & O’Grady, D. (2013). Digital video: the impact on children’s learning experiences in primary physical education. European Physical Education Review, 19(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X13486050.

Østerlie, O., & Kjelaas, I. (2019). The perception of adolescents’ encounterwith a flipped learning intervention in Norwegian physical education. Frontiers in Education, 4, 114. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00114.

Østerlie, O., & Mehus, I. (2020). The impact of flipped learning on cognitive knowledge learning and intrinsic motivation in Norwegian secondary physical education. Education Sciences, 10(4), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040110.

Palao, J. M., Hastie, P. A., Cruz, P. G., & Ortega, E. (2015). The impact of video technology on student performance in physical education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.813404.

Papastergiou, M., Natsis, P., Vernadakis, N., & Antoniou, P. (2020). Introducing tablets and a mobile fitness application into primaryschool physical education. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 799–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10289-y.

Penney, D., Jones, A., Newhouse, P., & Cambell, A. (2012). Developing a digital assessment in senior secondary physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 17(4), 383–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2011.582490.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2012). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Blackwell.

Potdevin, F., Vors, O., Huchez, A., Lamour, M., Davids, K., & Schnitzler, C. (2018). How can video feedback be used in physical education to support novice learning in gymnastics? Effects on motor learning, self-assessment and motivation. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 23(6), 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1485138.

Potter, J. (2009). Discourse analysis. In M. A. Hardy & A. Bryman (Eds.), Handbook of data analysis (pp. 607–624). SAGE.

Prohl, R. (2006). Grundriss der Sportpädagogik (2nd edn.). Limpert. Ground plan for sports pedagogy.

Quennerstedt, M., Gibbs, B., Almqvist, J., Nilsson, J., & Winther, H. (2016). Béatrice: dance video games as a resource for teaching dance. In A. Casey, V. A. Goodyear & K. M. Armour (Eds.), Digital technologies and learning in physical education: pedagogical cases (pp. 69–85). Routledge.

Quintas, A., Bustamante, J.-C., Pradas, F., & Castellar, C. (2020). Psychological effects of gamified didactics with exergames in physical education at primary schools: results from a natural experiment. Computers & Education, 152, 103874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103874.

Quintas-Hijós, A., Peñarrubia-Lozano, C., & Bustamante, J. C. (2020). Analysis of the applicability and utility of a gamified didactics with exergames at primary schools: qualitative findings from a natural experiment. PloS One, 15(4), e231269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231269.

Rekik, G., Khacharem, A., Belkhir, Y., Bali, N., & Jarraya, M. (2019). The instructional benefits of dynamic visualizations in the acquisition of basketball tactical actions. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12312.

Reynolds, C., Benham-Deal, T., Jenkins, J. M., & Wilson, M. (2018). Exergaming: comparison of on-game and off-game physical activity in elementary physical education. The Physical Educator, 75(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2018-V75-I1-7533.

Rincker, M., & Misner, S. (2017). The jig experiment: development and evaluation of a cultural dance active video game for promoting youth fitness. Computers in the Schools, 34(4), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2017.1387468.

Robinson, D., & Randall, L. (2017). Gadgets in the gymnasium: physical educators’ use of digital technologies | Les gadgets au gymnase: L’utilisation des technologies numériques par les enseignants en éducation physique. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology. https://doi.org/10.21432/T24C82.

Rojo-Ramos, J., Carlos-Vivas, J., Manzano-Redondo, F., Fernandez-Sanchez, M. R., Rodilla-Rojo, J., Garcia-Gordillo, M. A., & Adsuar, J. C. (2020). Study of the digital teaching competence of physical education teachers in primary schools in one region of Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238822.

van Rossum, T., & Morley, D. (2018). The role of digital technology in the assessment of children’s movement competence during primary school physical education lessons. In J. Koekoek & I. van Hilvoorde (Eds.), Digital technology in physical education: global perspectives. Routledge studies in physical education and youth sport series. (pp. 48–68). In: Routledge.

Roure, C., Méard, J., Lentillon-Kaestner, V., Flamme, X., Devillers, Y., & Dupont, J.-P. (2019). The effects of video feedback on students’ situational interest in gymnastics. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 28(5), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2019.1682652.

Sargent, J., & Casey, A. (2019). Flipped learning, pedagogy and digital technology: establishing consistent practice to optimise lesson time. European Physical Education Review, 26(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19826603.

Sheehan, D., & Katz, L. (2012). The impact of a six week exergaming curriculum on balance with grade three school children using the wii FIT+TM. International Journal of Computer Science in Sport, 11(3), 5–22.

Shewmake, C. J., Merrie, M. D., & Calleja, P. (2015). Xbox Kinect Gaming Systems as a supplemental tool within a physical education setting: third and fourth grade students’ perspectives. The Physical Educator. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2015-V72-I5-5526.

Shulruf, B. (2010). Do extra-curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56(5/6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9180-x.

Sohnsmeyer, J. (2011). Virtuelles Spiel und realer Sport: Über tranferspotenziale digitaler Sportspiele am Beispiel von Tischtennis [Virtual game and real sport—About transfer potential of digital sports games using the example of table tennis. Forum sportwissenschaft, Vol. 21. (Vol: Feldhaus Ed. Czwalina. Doctoral dissertation, University of Kiel.

Steinberg, C., Zühlke, M., Bindel, T., & Jenett, F. (2020). Aesthetic education revised: a contribution to mobile learning in physical education. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 50(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-019-00627-9.

Sun, H. (2012). Exergaming impact on physical activity and interest in elementary school children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 83(2), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2012.10599852.

Sun, H. (2013). Impact of exergames on physical activity and motivation in elementary school students: a follow-up study. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 2(3), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.02.003.

Tou, N. X., Kee, Y. H., Koh, K. T., Camiré, M., & Chow, J. Y. (2020). Singapore teachers’ attitudes towards the use of information and communication technologies in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 26(2), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19869734.

Trabelsi, O., Gharbi, A., Masmoudi, L., & Mrayeh, M. (2020). Enhancing female adolescents’ engagement in physical education classes through video-based peer feedback. Acta Gymnica, 50(3), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.5507/ag.2020.014.

Vega-Ramirez, L., Notario, R. O., & Avalos-Ramos, M. A. (2020). The relevance of mobile applications in the learning of physical education. Education Sciences, 10(11), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110329.

Wadsworth, D., Brock, S., Daly, C., & Robinson, L. (2014). Elementary students’ physical activity and enjoyment during active video gaming and a modified tennis activity. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 14(3), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2014.03047.

Weir, T., & Connor, S. (2009). The use of digital video in physical education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 18(2), 155–171.

Ye, S., Lee, J. E., Stodden, D. F., & Gao, Z. (2018). Impact of exergaming on children’s motor skill competence and health-related fitness: a quasi-experimental study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7090261.

Zhu, X., & Dragon, L. A. (2016). Physical activity and situational interest in mobile technology integrated physical education: a preliminary study. Acta Gymnica, 46(2), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.5507/ag.2016.010.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F. Jastrow, S. Greve, M. Thumel, H. Diekhoff and J. Süßenbach declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. The studies listed were subject to ethical guidelines.

Rights and permissions