Abstract

Delivery is a stressful and risky event menacing the newborn. The mother-dependent respiration has to be replaced by autonomous pulmonary breathing immediately after delivery. If delayed, it may lead to deficient oxygen supply compromising survival and development of the central nervous system. Lack of oxygen availability gives rise to depletion of NAD+ tissue stores, decrease of ATP formation, weakening of the electron transport pump and anaerobic metabolism and acidosis, leading necessarily to death if oxygenation is not promptly re-established. Re-oxygenation triggers a cascade of compensatory biochemical events to restore function, which may be accompanied by improper homeostasis and oxidative stress. Consequences may be incomplete recovery, or excess reactions that worsen the biological outcome by disturbed metabolism and/or imbalance produced by over-expression of alternative metabolic pathways. Perinatal asphyxia has been associated with severe neurological and psychiatric sequelae with delayed clinical onset. No specific treatments have yet been established. In the clinical setting, after resuscitation of an infant with birth asphyxia, the emphasis is on supportive therapy. Several interventions have been proposed to attenuate secondary neuronal injuries elicited by asphyxia, including hypothermia. Although promising, the clinical efficacy of hypothermia has not been fully demonstrated. It is evident that new approaches are warranted. The purpose of this review is to discuss the concept of sentinel proteins as targets for neuroprotection. Several sentinel proteins have been described to protect the integrity of the genome (e.g. PARP-1; XRCC1; DNA ligase IIIα; DNA polymerase β, ERCC2, DNA-dependent protein kinases). They act by eliciting metabolic cascades leading to (i) activation of cell survival and neurotrophic pathways; (ii) early and delayed programmed cell death, and (iii) promotion of cell proliferation, differentiation, neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis. It is proposed that sentinel proteins can be used as markers for characterising long-term effects of perinatal asphyxia, and as targets for novel therapeutic development and innovative strategies for neonatal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Perinatal asphyxia: a long-lasting metabolic insult

A temporal interruption of oxygen availability implies a risky metabolic challenge whenever the insult is not leading to a fatal outcome. Interruption of oxygen availability at birth implies a radical shift from an aerobic to a less efficient anaerobic metabolism, resulting in (i) a decrease of the rate of ATP formation (Lubec et al. 2000; Seidl et al. 2000); (ii) lactate accumulation (Chen et al. 1997a); (iii) decreased pH (Engidawork et al. 1997; Lubec et al. 2000), and (iv) over production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Kretzchmar et al. 1990; Hasegawa et al. 1993; Ikeda et al. 1999; Tan et al. 1999). ATP deficit implies a weakened electron transport pump (Numagani et al. 1997), intracellular calcium accumulation (Akhter et al. 2000) and, if prolonged, DNA fragmentation (Akhter et al. 2001).

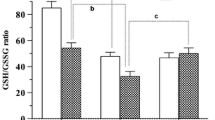

Re-oxygenation is a requisite for survival, but it can lead to improper homeostasis, partial recovery and sustained over-expression of alternative metabolic pathways, prolonging the energy deficit and/or generating oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has been indicated as a factor associated with inactivation of a number of enzymes; including mitochondrial respiratory enzymes (see Gitto et al. 2002).

Clinical relevance

Perinatal asphyxia still occurs frequently whenever delivery is prolonged, despite improvements in perinatal care (Berger and Garnier 2000; Volpe 2001; Low 2004; Vannuci and Hagberg 2004). The international incidence has been reported to be 2–6/1,000 term births (de Hann et al. 2006), reaching larger rates in developing countries (Lawn et al. 2005). After asphyxia, infants can suffer from long-term neurological sequelae, the severity of which depends upon the extent of the insult. Severe asphyxia has been linked to cerebral palsy, mental retardation and epilepsy, while mild-severe asphyxia has been associated with attention deficits and hyperactivity in children and adolescents (Mañeru et al. 2001, 2005). No strict correlation has been demonstrated yet between the clinical outcome and the severity and/or the extent of the insult, but there is a correlation between recovery and outcome (Bracci et al. 2006; Triulzi et al. 2006; Perlman 2006). In a recent cohort study monitoring 5,887 children for 8 years, it was shown that resuscitated infants, asymptomatic for encephalopathy, showed an increased risk for low IQ score (Odd et al. 2009).

In the clinical scenario, after resuscitation, the emphasis is on supportive therapy to stabilize systemic physiological parameters. Many concepts have been put forth to prevent the long-term neurological consequences of the insult, or about procedures to re-establish oxygenation without further worsening the outcome, but, only hypothermia has been shown to be neuroprotective both experimentally and clinically. While several meta-analysis studies have reported promising results (Edwards 2009; Shah 2010), there is still a need for further research demonstrating a long-term neuroprotective value (Azzopardi et al. 2009; see Groenendaal and Brouwer 2009; Edwards 2009; Shah 2010). A major limitation is the rather narrow therapeutic window, as clearly demonstrated by convincing experimental studies (Engidawork et al. 2001; Roelfsema et al. 2004; Hoeger et al. 2006). Furthermore, van den Broek et al. (2010) have recently discussed the proposed roles of hypothermia in modifying several pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic features of drugs used in neonatology.

Regional and developmental vulnerability

Amongst other brain regions, neurocircuitries of the basal ganglia, but also of hippocampus, are particularly vulnerable to global anoxia/ischaemia occurring at neonatal (Pasternak et al. 1991; Pastuzko 1994; Cowan et al. 2003; Miller et al. 2005; Barkovich 2006) and adult stages (Pulsinelli et al. 1982; see Haddad and Jiang, 1993; Calabresi et al. 2000; Venkatesan and Frucht, 2006). Our previous study confirmed that vulnerability, assayed with immunochemistry (Andersson et al. 1995; Dell’Anna et al. 1997; Chen et al. 1997a, b; Morales et al. 2003, 2005; Klawitter et al. 2005), molecular biology (Andersson et al. 1995; Gross et al. 2000, 2005), in vivo (Dell’Anna et al. 1995;1997; Chen et al. 1997c), in vitro (Morales et al. 2003; Klawitter et al. 2005, 2006, 2007) and/or ex vivo (Ungethüm et al. 1996; Chen et al. 1997c; Bustamante et al. 2003) biochemistry, supporting the idea that the regional impact of the insult is related to (i) the severity (extent) of the insult; (ii) the metabolic imbalance during the re-oxygenation period, and (iii) the developmental stage of the affected region.

The immature brain is particularly vulnerable to metabolic insults, including oxidative stress. Along a series of seminal studies, Ralf Dringen in Tuebingen, Germany (Dringen 2000; Dringen et al. 2005), demonstrated that, during development, antioxidant mechanisms are not sufficiently expressed and do not respond to oxidative stress in a comparable manner to the adult brain (see also McQuillen and Ferreiro 2004). This is attributed partly to high fatty acid content of the young brain, its high oxygen consumption and oxidative phosphorylation (Dringen et al. 2005).

In the central nervous system (CNS) of mammals, including man, neuronal and glial growth and differentiation are predominantly postnatal events (Altman 1967). Neuronal migratory pathways have different developmental time-courses, e.g. dopamine-containing neuronal pathways have an earlier and faster development than noradrenaline- and 5-hydroxytryptamine pathways (Loizou 1972). Similarly, mesencephalic and telencephalic structures are differently developed at birth and the functional development of striatal neurocircuitries depends upon mesencephalic and neocortical inputs. The neocortex largely matures at postnatal stages. Indeed, in the rat, neocortical pyramidal projections enter physiologically viable states only 1 week after birth (Li and Martin 2000; Meng and Martin 2003; Meng et al. 2004). Furthermore, while the rat at postnatal day 1 (P1) possesses the same number of dopamine cell bodies as in adulthood, proliferation of their terminal network is largely undeveloped (Olson and Seiger 1972; Loizou 1972; Seiger and Olson 1973; Voorn et al. 1988). Dopamine fibres start to invade the neostriatum before birth (Seiger and Olson 1973), but dopamine-containing axon terminals reach a peak at the fourth postnatal week, and a mature targeting is only achieved after several postnatal weeks, when patches are replaced by a diffuse dopamine innervation pattern (Antonopoulos et al. 2002). Indeed, dopaminergic axons continue to grow at a slow rate during adulthood (Loizou 1972; Voorn et al. 1988). There are also waves of naturally dying dopamine neurons occurring postnatally, which increases the susceptibility of surviving neurons to energy failure (Oo and Burke 1997; Antonopoulos et al. 2002).

Early and delayed cell death

Cell death can occur by different mechanisms, i.e. necrosis, following severe fulminate insults, or apoptosis, whenever the organism has time to organize a programmed death. Necrosis can be observed within minutes, while apoptosis takes more time to develop (Bonfocco et al. 1995). No gross morphology indicating necrotic cell death has been found in rat pups surviving short- or long-periods of perinatal asphyxia, when the main experimental parameter is anoxia (Dell’Anna et al. 1997). Nevertheless, several neurochemical and immunocytochemical studies have shown specific neuronal changes at short (Dell’Anna et al. 1995; Chen et al. 1997a), and extended time intervals after the insult (Andersson et al. 1995; Dell’Anna et al. 1997, Chen et al. 1997a, b, c), which may explain behavioural and cognitive deficits occurring with a delayed onset (Chen et al. 1995; Simola et al. 2008; Morales et al. 2010).

Dell’Anna et al. (1997) studied changes in nuclear chromatin fragmentation at 80 min to 8 days after perinatal asphyxia, observing a progressive and delayed increase in nuclear fragmentation that was dependent upon the duration of the perinatal insult. The most evident effects were seen in frontal cortex, neostriatum and cerebellum at P8. These observations have been replicated by several laboratories, suggesting an apoptotic mechanism (Nakajima et al. 2000; Northington et al. 2001; Morales et al. 2008). This can be a rather simplified view, because cell death phenotypes can be heterogeneous after neonatal insults. Indeed, apoptotic cells can undergo secondary necrosis, when the amount of apoptosis overwhelms the ability of the tissue to remove the cellular debris by phagocytosis (Bonfocco et al. 1995; Portera-Cailliau et al. 1997a, b). While phagocytosis is probably accomplished by microglia, there is an autophagic mechanism in each cell for sequestration of proteins and damaged organelles into vesicles named autophagosomes, which are fused with lysosomes for degrading their contents (see Shintani and Klionsky 2004). In neurons, autophagy can be linked to apoptosis, but it can represent an independent programmed cell death, also increased by neonatal hypoxia/ischaemia (Ginet et al. 2009). Several protein families involved in apoptosis are activated by neonatal hypoxia–ischaemia including BCL-2 and BCL-XL, which promote survival (Howard et al. 2002), and BAX, BID, BCL-XS and BAD, which promote cell death (Yang et al. 1995; see Morales et al. 2008). Moreover, members of the death-associated protein kinase family, DAPK and DRP-1 have been associated to autophagy by a caspase-independent mechanism (see Shintani and Klionsky 2004).

Postnatal neurogenesis

Postnatal neurogenesis occurs in dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus and subventricular zone (SVZ) of mammals, including humans (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim 2004; Ming and Song 2005; Zhao et al. 2008), probably for neuronal replacement. Indeed, increased neurogenesis has been observed in the SVZ following anoxic/ischaemic insults, producing neuroblasts that can migrate, differentiate and develop to functionally competent neurons, to be integrated into injured areas (Collin et al. 2005, Bédard et al. 2006). Neuroblasts from the subgranular zone of the DG migrate to the inner granular cell layer, their axons project to the CA3, and their dendrites extend into the molecular layer (Hastings and Gould 1999). Several reports have shown that neurogenesis in the DG is increased following anoxic/ischaemic insults (Scheepens et al. 2003; Bartley et al. 2005; Morales et al. 2005, 2008).

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) has been identified as a factor promoting cell survival and neurogenesis (Takami et al. 1992; Cheng et al. 2002, Ganat et al. 2002), through activation of the MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) pathway (Mudò et al. 2009; Morales et al. 2008). Along these lines, the expression of bFGF has been observed to be upregulated in DG and SVZ following perinatal asphyxia (Plane et al. 2004; Morales et al. 2008; Suh et al. 2009), possibly to prevent cell death (Han and Holtzman 2000). Several proteins have been identified as modulators of the transduction cascade elicited by bFGF receptors (FGFR) during embryogenesis, including Spry, Sef and FLRT3 (Tsang and Dawid 2004). Spry and Sef provide inhibitory regulation, while FRLT3 stimulates the activation of FGFR and ERK (Tsuji et al. 2004). Interestingly, ERK2 phosphorylation is modulated by PARP-1, promoting the expression of c-fos (Cohen-Armon et al. 2007), directly or via Elk1. bFGF requires proteoglycans to achieve full activation of FGFR, involving the action of phosphatases and the formation of a ternary complex, comprised by the proteoglycan syndecan-4, phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) and protein kinase Cα (PKCα) (Horowitz et al. 2002). Whether these pathways occur postnatally to regulate the cellular response to injury is not yet known.

Proteins involved in cell migration, neurite outgrowth and synaptic targeting

Several cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily are involved in cell migration, neurite outgrowth and synaptic targeting. L1 and β1 integrins converge with growth factor signalling, activating the MAPK/ERK pathways. L1 also interacts with Ephrin/EphB proteins, promoting axon branching (see Schmid and Maness 2008). Additionally, L1 promotes homophilic interactions with L1 itself, as well as a number of different heterophilic interactions with molecules including αvβ3 integrin, axonin-1 and contactin/F3 to promote neurite outgrowth (Zhao et al. 1998; De Angelis et al. 1999; Ruppert et al. 1995; Montgomery et al. 1996). More than 100 mutations in L1 have been found in humans, associated with severe neurological dysfunctions, including agenesis of the corticospinal tract and the corpus callosum, spastic paraplegia and mental retardation (Kenwrick et al. 2000), supporting its role in CNS development. L1 localises in the same compartment as microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2), a somatodendritic marker (Demyanenko et al. 1999). Furthermore, it has been reported that the hippocampus of L1 mutant mice is smaller than in normal animals, suggesting that L1 is relevant for the regulation of hippocampal development (Demyanenko et al. 1999). L1 also plays a function in the organization of dopaminergic neurons in mesencephalon and diencephalon, modulating extension of growth cones to different synaptic targets (Demyanenko et al. 2001).

Neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis require specificity, which has to be preserved when building functional neurocircuitries. Hence, the relevance of inhibitory proteins, such as Thy-1 and Nogo receptor (NgR), counteracting the effect of stimulatory proteins, such as L1, is highly relevant. Thy-1 is abundantly expressed on the surface of most neurons in the CNS, but its expression is regulated during development, appearing in the early postnatal period (Morris et al. 1985). Thy-1 has been considered to be a cell adhesion molecule belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily. However, many studies now support the idea that Thy-1 plays the role of an inhibitory protein modulating axonal growth (Morris et al. 1992; Chen et al. 2005). Indeed, it has been suggested that Thy-1 limits axonal growth in order to stabilize neuronal connections during postnatal development (Morris et al. 1992; Barlow and Huntley 2000).

The inhibitory function of Thy-1 in neurons occurs by binding to expressed by astrocytes (Tiveron et al. 1992; Dreyer et al. 1995). Our previous studies indicate that upon binding to both αvβ3 integrin and syndecan-4, Thy-1 triggers tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins, increases RhoA activity and promotes the attachment and spreading of astrocytes (Leyton et al. 2001; Avalos et al. 2002, 2004, 2009; Hermosilla et al. 2008). It has not yet been reported whether binding of Thy-1 to αvβ3 prevents neurite extension. Thus, the regulation of neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis by bFGF, L1 and Thy-1 is exciting in that they interact with syndecan-4 and/or αvβ3 integrin, but triggering opposite effects. The fine tuning of these events likely is controlled by the temporal and spatial expression of these proteins. Indeed, (i) αvβ3 integrin is not normally expressed in the adult brain, but it is expressed after stroke or other brain insults (Ellison et al. 1998); (ii) syndecan-4, although ubiquitously expressed in small amounts, up-regulates its mRNA and core protein levels at day 4 post-injury (Iseki et al. 2002).

NgR is also a neuronal protein inhibiting neurite outgrowth. The expression of NgR and its ligand Nogo-A are up-regulated in rats subjected to hypoxia–ischaemia at P7, indicating their relevance to metabolic insults affecting neonates (Wang et al. 2006). Nogo-A is expressed in myelin-forming oligodendrocytes, and inhibition of either the receptor or the ligand leads to axonal sprouting and functional recovery of damaged neurons (Wiessner et al. 2003; Li et al. 2005), supporting the idea of NgR as an inhibitory protein regulating neuronal processes. Astrocyte αvβ3 integrin and other oligodendrocytes, but also neuronal proteins, provide targets for modulating brain regeneration capacity, and open therapeutic avenues for individuals affected by hypoxia. Indeed, perinatal asphyxia has been associated with an increased sprouting in stratum oriens of dorsal hippocampus, promoting the formation of new recurrent excitatory branches from the mossy fibre projection to the CA3 region (Morales et al. 2010).

Sentinel proteins

Suppression and/or over-activation of gene expression occurs immediately or during the re-oxygenation period following perinatal asphyxia (Labudova et al. 1999; Seidl et al. 2000; Mosgoeller et al. 2000; Lubec et al. 2002). When the DNA integrity is compromised, a number of sentinel proteins are activated, including (i) poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) (Amé et al. 2004); (ii) X-ray Cross-Complementing Factor 1 (XRCC1) (Green et al. 1992); (iii) DNA ligase IIIα (Leppard et al. 2003); (iv) DNA polymerase β (Wilson 1998; Mishra et al. 2003); (v) Excision Repair Cross-Complementing Rodent Repair Group 2 (ERCC2) (Sung et al. 1993; Chiappe-Gutierrez et al. 1998; Lubec et al. 2002) and (vi) DNA-dependent protein kinases (de Murcia and Menissier de Murcia 1994).

PARP proteins act as ADP-ribose transferases, transferring ADP-riboses from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to glutamic and aspartic residues of the PARPs and their substrates. PARPs also catalyse the polymerization of ADP-riboses via glycosidic bonds, creating long and branched ADP-ribose polymers. PARP-1 is the most abundant and conserved member of a large superfamily comprising at least 18 PARP proteins, encoded by different genes, but displaying a conserved catalytic domain (see Amé et al. 2004). PARP-1 is involved in DNA repair, but it might also promote cell death (De Murcia and Menissier de Murcia 1994; see recently Kauppinen and Swanson 2007; Cohen-Armon 2008). When DNA damage is mild, PARP-1 is involved in the maintenance of chromatin integrity, by signalling cell-cycle arrest and/or by activating DNA repairing molecular cascades. PARP-1 is also involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation, and modulates the transcription of several inflammatory signals, including Nuclear Factor (NF)-κB (Hassa and Hottinger 1999). Excessive PARP-1 activation leads to NAD+ exhaustion and energy crisis (Berger 1985), and to caspase-independent apoptosis, via translocation of the mitochondrial pro-apoptotic protein Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) to the nucleus, initiating nuclear condensation (Jiang et al. 1996; Yu et al. 2002; Hong et al. 2004), and a cascade of events exacerbating the biological outcome. Thus, PARP-1 has been shown to be involved in the long-term effects produced by perinatal asphyxia (Martin et al. 2005). However, other sentinel proteins are probably involved as well, modulating epigenetic processes, such as methylation (Caiafa et al. 2009), acetylation (Rajamohan et al. 2009) and phosphorylation (Cohen-Armon et al. 2007), rendering access to information that is present in the DNA without inducing genetic mutation (see Caiafa et al. 2009).

Sentinel proteins cross-talk

PARP-1, XRCC1, DNA ligase IIIα and DNA polymerase-β are molecular partners, working in tandem to repair single-strand breaks. DNA ligase IIIα has an N-terminal zinc finger interacting with the DNA binding domain of PARP-1 and the DNA strand breaks. DNA Ligase IIIα also interacts with XRCC1, resulting in the formation of a DNA Ligase IIIα-XRCC1 complex (see Ellenberger and Tomkinson 2008). DNA polymerase-β is functionally coupled to PARP-1, DNA Ligase IIIα and XRCC1, although the molecular basis for that coupling has not yet been clarified. However, DNA polymerase-β and XRCC1 bind to single-strand breaks, contributing to the overall stability of the repair complex, promoting polymerase catalysis and fidelity (Sawaya et al. 1997). Both PARP-1 and DNA polymerase-β are increased by hypoxia induced in newborn piglets (Mishra et al. 2003). XRCC1 expression is also increased by perinatal asphyxia (Chiappe-Gutierrez et al. 1998). Indeed, using an ischaemic preconditioning model, Li et al. (2007) demonstrated a five-fold increase of XRCC1 levels 30 min after ischaemia, reaching a maximal expression after 4 h. DNA polymerase-β and DNA ligase IIIα levels were also increased, and co-expressed in neuronal, but not in glial cells. Interestingly, however, only DNA ligase IIIα levels were increased in glial cells, suggesting cell-type specificity (Li et al. 2007). PARP-1 can be phosphorylated by ERK, probably via the isoform 2 (ERK2), as a requirement for maximal PARP-1 activation after DNA damage (Kauppinen et al. 2006). It has also been suggested that PARP-1 can be phosphorylated by PKC, but leading to down-regulation (Tanaka et al. 1987; Bauer et al. 1992). Cohen-Armon et al. (2007) have reported evidence for PARP-1 activation by phosphorylated ERK2, in the absence of DNA damage, via the signalling cascade of the transcription factor Elk1, increasing the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos, stimulating cell growth and differentiation. It will be important to further study how these sentinel proteins are expressed in in vitro and in vivo models, and to develop therapeutic targets for inhibiting the metabolic cascade elicited by perinatal asphyxia. Cell-type specificity and regional distribution of sentinel proteins may constitute regulatory mechanisms by which the long-term effects of metabolic insults occurring at birth become heterogeneous, targeting some, but leaving other brain regions apparently untouched.

PARP-1 as a target for neuroprotection

PARP-1 inhibition is emerging as a target for neuroprotection following hypoxia/ischaemia. The strongest evidence for this hypothesis comes from studies showing that ischaemic injuries are markedly decreased in PARP(−/−) mice (Eliasson et al. 1997; Harberg et al. 2004). It supports previous findings that PARP inhibitors, with increasing degrees of potency, decrease brain damage and improve the neurological outcome of perinatal brain injury (Zhang et al. 1995; Ducrocq et al. 2000; Sakakibara et al. 2000; see Virag and Szabo 2002).

The idea that PARP-1 activation is beneficial has also been explored, depending upon the actual levels of cellular NAD+. While PARP inhibitors offer remarkable protection under conditions of NAD+ and ATP depletion, inhibition of PARP-1 in the presence of NAD+ sensitises cells to DNA damage, and subsequent increase of cell death (Nagayama et al. 2000). Furthermore, it has been reported that inhibition of PARP-1 can induce apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells (Saldeen and Welsh 1998), possibly by blocking the access of replication or repair enzymes to DNA. G2 cell-cycle arrest may be promoted followed by p53-independent apoptosis (Saldeen et al. 2003), and resultant inhibition of cell proliferation.

Indeed, PARP-1 acts as both a cell survival and cell death inducing factor by regulation of DNA repair, chromatin remodelling and regulation of transcription. PARP-1 overactivation following (hypoxic) stress conditions may occur by p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) mediated acetylation, resulting in caspase-independent translocation of AIF from mitochondria to the nucleus and subsequent cell death by ‘chromatinolysis’. PARP-1 activation is essential for AIF truncation and release from mitochondria (Kolthur-Seetharam et al. 2006). Apart from those molecular interactions, PARP-1 catalyses most poly-ADP-ribosylations of proteins in vivo. PARP-1 interacts with proteins of the sirtuin (SIRT) family, histone deacetylases (HDAC) type III, promoting cell survival (Amé et al. 2004). Interestingly, PARP-1 deacetylation by SIRT results in its inactivation. Apparently, the well-adjusted equilibrium between SIRT and PARP-1 is maintained by their strict dependency from and competition for NAD+. Increased demand for NAD+ by PARP-1 inhibits SIRT and vice versa (Rajamohan et al. 2009). PARP-1 activity is also under control of, and controls in a reciprocal manner the activity of H1-histone, which results in exclusion of H1 from a subset of PARP-regulated promoters and subsequent regulation of chromatin structure.

PARP-1 itself can be poly-ADP-ribosylated (PARylated PARP), which is reversed by poly-ADP-ribose glycohydrolase (PARG). There is a link between poly-ADP-ribosylation and DNA methylation, implying DNA silencing. Indeed, it has been shown that PARG overexpression, or reduction of PARylated PARP, results in methylation of CpG islands in the DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) promoter (Zampieri et al. 2009). The ensuing gene silencing leads to widespread, passive DNA hypomethylation, which results in gene expression. Conversely, when PARylated PARP occupies the DNMT1 promoter, it protects its unmethylated state and DNMT transcription. Additionally, other transcription factors, such as p300, sex determining region Y (SRY), or E2F transcript factor, are associated with PARP-1 and the DNMT1 promoter (Rajamohan et al. 2009). In summary, PARP and SIRT are at the core of epigenetic actions encompassing DNA and histone modifications.

An experimental model of perinatal asphyxia

While the short- and long-term clinical outcome of perinatal asphyxia is well established, pre-clinical research is still at an exploratory phase, mainly because of a lack of consensus on a reliable and predictable experimental model. A model for investigating the issue was proposed at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, at the beginning of the 1990s (Bjelke et al. 1991; Andersson et al. 1992; Herrera-Marschitz et al. 1993). Despite the fact that the model is now run by several laboratories around the world, its acceptance has not been easy, because the model works with on term pups and not with neonates at P7. The main argument for criticizing the model has been that the brain of neonate rats is premature when compared to the neonatal human brain, a statement mainly referring to the neocortex (see Romijn et al. 1991), but also to the pattern of oligodendrocyte lineage progression required for cerebral myelination (Craig et al. 2003). The degree of maturity depends upon the tissue and functions selected for the comparisons, and vulnerability to injury may be related to both the timing and the location of the insult (Craig et al. 2003, see also de Louw et al. 2002). Indeed, it has been reported that susceptibility to hypoxia/ischaemia induced by common carotid artery ligation and hypoxemia is greater when performed at P7 rather than at earlier postnatal periods (Towfighi et al. 1997). We have chosen a rather pragmatic approach, inducing asphyxia at the time when rats are delivered. Several features support the usefulness of the present model: (i) it mimics well some relevant aspects of human delivery; (ii) it is largely non-invasive; (iii) it allows studying short- and long-term consequences of the insult in the same preparation, and (iv) it is highly reproducible among laboratories. Lubec et al. in Vienna (Austria) (Lubec et al. 1997a, b; Seidl et al. 2000) have stressed the issue that the model is suitable for studying the early phase of perinatal asphyxia, as observed in the clinical setup, but performed at term, during delivery. The same authors acknowledge the fact that the model implies oxygen interruption, but not any additional lesion, including vessel occlusion. Moreover, it is followed by hypoxemia, acidosis and hypercapnia, mandatory criteria for a clinically relevant model of perinatal asphyxia (Seidl et al. 2000).

The model starts by an evaluation of the oestral cycle of young female Wistar rats (~2 months of age), in order to plan for a programmed mating. A vaginal frotis is taken for evaluating the cycle, identifying pro-oestrus, oestrus, meta-oestrus or di-oestrous, as shown in Fig. 1. The female is exposed to a male at the time of the pro-oestrous for one night and thereafter the presence of a vaginal clot is evaluated. Thus, the time of delivery is calculated, supported by ethological and clinical observations, to predict the exact time of delivery (22 days after a vaginal clot has been recorded). At the time of delivery, a first spontaneous delivery can be observed before the dams are anaesthetized, neck dislocated and subjected to a caesarean section and hysterectomy. The uterine horns containing the foetuses are immediately immersed into a water bath at 37°C for various periods of time (0–22 min). Following asphyxia, the pups are removed from the uterine horns and resuscitated by cleaning the faces of the animals from fluid and amniotic tissue, freeing the mouth and the nose (Fig. 2). Further additional efforts and care are taken to induce pulmonary breathing by touching the surface of the nose and mouth, as well as pressing the thorax. Pups exposed to caesarean delivery only (CS, 0 asphyxia), or to mild asphyxia (2–10 min) are rapidly resuscitated, without requiring anything else but removing fluid and amniotic tissue from the head. Pups exposed to zero or mild asphyxia start breathing with a gluttonous gasp, which is rapidly replaced by regular and synchronized breathing. For pups exposed to longer periods of asphyxia (19–21 min), resuscitation implies expert and skilful handling, and it takes a long time (4–6 min) for a first gasping, and even longer time for establishing a more or less regular breathing, always supported by gasping (Fig. 2). After 80 min of care taking, the pups are given to surrogate dams for nursing, pending further experiments. An Apgar scale is applied during the recovery period, similar to that observed in neonatal units.

Evaluation of the oestral cycle in vaginal frotises from young female Wistar rats. A vaginal frotis is taken for evaluating the cycle, identifying pro-oestrus, oestrus, meta-oestrus or di-oestrous. In a, cells are in pro-oestrus: many globular, no differentiated epithelial cells are seen, showing an apparent nucleus (thin arrow). Some differentiated flat cells, without any apparent nucleus, are also observed (wide arrow). In b, cells are in oestrus: many differentiated epithelial cells are seen (arrows). In c, cells are in meta-oestrus: many degrading epithelial cells are seen (arrows) as well as leukocytes (head arrow). In d, cells are in di-oestrus: leukocytes are the predominant type of cells (from Klawitter 2006). Identifying a successful mating will lead to an accurate estimation of delivery, as well as to a decrease in the number of uncontrolled delivery impeding the performance of the experiment. This is not a trivial outcome, because it will safe experimental animals with the consequent bioethical implications

The Karolinska Institutet experimental model of perinatal asphyxia. The experiment starts by an evaluation of the oestral cycle of young female Wistar rats (~2 months of age), in order to plan for a programmed mating. The female is exposed to a male at the time of the pro-oestrous for one night and thereafter the presence of a vaginal clot is evaluated. Pregnancy is continuously monitored until delivery of a first pup is observed (representing a vaginally delivered control), or when the maturity of the foetuses is assessed by clinical abdominal palpation, indicating that the dam is ready for delivery (~22 days after the identification of a vaginal clot). The animal is anaesthetised, killed by neck dislocation and subjected to a caesarean section and hysterectomy. The uterine horns are then immersed into a temperature-controlled water bath (37°C) for various periods of time. One or two pups are immediately delivered after hysterectomy, representing a caesarean-delivered control. After asphyxia, the pups are removed from the uterine horns and resuscitated by cleaning the faces of the animals from fluid and amniotic tissue, freeing the mouth and the nose, and stimulated to pulmonary breathing. Pulmonary breathing is further monitored and the surviving pups are evaluated by an Apgar scale 40–60 min after delivery. Thereafter the pups are given to surrogate dams for nursing (delivering immediately before the hysterectomised dam), pending further experiments (see Dell’Anna et al. 1997; Klawitter et al. 2007)

An Apgar scale for rodents

Table 1 shows the main parameters evaluated by an Apgar scale, including weight, sex, colour of the skin, respiratory frequency and presence of gasping, vocalization, muscular rigidity and spontaneous movements (Dell’Anna et al. 1997; Morales et al. 2010). The Apgar evaluation is a critical parameter for this experimental model, because it assesses whether the pups are subjected to mild or to severe asphyxia, which is directly determined by the percentage of survival and recovery (Herrera-Marschitz et al. 1993, 1994). Survival is a straightforward parameter. 100% survival is observed whenever foetuses-containing uterine horns are immersed for up to 15 min in a water bath at 37°C. Thereafter, the rate of survival drops rapidly, until no survival is observed following 22 min of asphyxia (Fig. 3). The temperature of the water bath is a critical parameter to be tightly controlled, because each degree below 37°C is associated with longer survival (Herrera-Marschitz et al. 1993, 1994; Engidawork et al. 2001). The recovery period can also add or prolong a hypoxic/ischaemic condition, as the surviving pups may show a decreased breathing rate, decreased cardiovascular function and low peripheral and/or central blood perfusion (Table 1). The Apgar evaluation also provides information about the condition shown by the caesarean-delivered control pups, which has to be similar to that shown by vaginally delivered pups. Thus, the Apgar evaluation is a requirement when using the present model of perinatal asphyxia, because it permits to compare results obtained by different laboratories and/or different treatments. The quality of the handling of the pups and the experience of the surrogate dam are important factors for the acceptance and nursing of both asphyxia-exposed and control pups.

Survival and ATP levels in peripheral organs and brain. Survival rate and ATP levels (%) found 10 min after delivery of asphyxia-exposed and control (caesarean delivery only, zero asphyxia) rat pups. Perinatal asphyxia was performed by immersion of pup containing uterine horns into a water bath at 37°C, removed by a caesarean section from ready-to-deliver rats. Ten minutes after delivery, asphyxia-exposed and control animals were decapitated for removing brain, heart and kidneys, to be treated according to Engidawork et al. (2001), for measuring energy-rich phosphates by HPLC coupled to a UV detector according to Ingebretsen et al. (1982). In control animals, ATP levels were 1.2 ± 0.2; 4.7 ± 0.1; and 1.6 ± 0.3 μmol/g wet wt in brain (n = 7), heart (n = 16) and kidneys (n = 16), respectively, 10 min after caesarean delivery (n = 7). Filled circles survival rate; filled inverted triangles ATP in brain; filled squares ATP in heart; filled triangles ATP in kidneys. Vertical line marks the time (15 min) when survival rate starts to drop; horizontal line marks 50%. Abscissa time (min) of immersion into a water bath at 37°C (asphyxia); ordinate survival in percentage (%). Compared to zero asphyxia

Short-term effects produced by perinatal asphyxia

Apart from the effects produced by perinatal asphyxia on the survival rate, the model has been shown to be useful for describing some early molecular, metabolic and physiological effects observed minutes after recovering from a caesarean delivery, without any asphyxia, or from mild or severe insults. Behavioural scales are normally applied 40–80 min after delivery to avoid competing with the resuscitating and nursing manoeuvres. Tissue sampling can be started soon after delivery. For measures of molecular markers, tissue samples are collected immediately after delivery, the time when the pups are removed from the uterine horns (0 min, with or without previous immersion into a water bath).

For measuring energy metabolism, tissue samples were taken from peripheral organs (heart and kidneys) and brain, removed from asphyxia-exposed and control animals 10 min after delivery and stored at −80°C until analysis (Lubec et al. 1997a, b; Seidl et al. 2000; Engidawork et al. 2001). Tissue samples were assayed for (i) energy-rich phosphates (including ATP, ADP, AMP, Cr and PCr); (ii) PKC and cyclin dependent kinases (Cdk); (iii) antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase); (iv) peroxidation products; (v) lactate, and (vi) pH.

Among the monitored energy-rich phosphates, ATP levels showed the most evident changes, following or anticipating the final outcome of perinatal asphyxia. In Fig. 3, the rate of survival is plotted together with the changes (in percentage) of ATP levels measured 10 min after delivery in brain, heart and kidneys. It can be seen that the kidneys were the first organs reacting to oxygen interruption. ATP levels in kidneys were decreased by >90% after 5 min of perinatal asphyxia, while ATP levels in heart and brain were only decreased by ~20% compared with levels observed after no asphyxia. Only after 15 min of asphyxia, ATP levels in heart and brain started to decrease, by approximately 70% compared with control levels, together with a simultaneous drop in the survival rate. After longer periods of asphyxia, ATP levels were decreased by >90% in the brain, but only by approximately 80% in the heart after 20 min of asphyxia, when the survival rate dropped by >70%. These changes in ATP levels nicely agree with the well-established idea of privileged organs regarding energy availability. The kidneys are bypassed in favour of heart and brain, but then the brain is given up in favour of the heart that has to keep working if any hope for survival remains. In agreement, as shown in Fig. 4, PCr levels rapidly decreased in kidneys and brain according to the length of asphyxia, but were largely preserved in the heart up to the final outcome, probably as a reservoir for the generation of ATP, as observed during periods of muscular exertion. Indeed, it has been suggested that PCr levels constitute a dynamic metabolic pool that can facilitate transfer of high energy phosphate equivalents from sites of ATP production at mitochondria to remotes sites of ATP utilization, functioning as a ‘phosphocreatine shuttle’ (Friedman and Roberts 1994). It is unlikely that changes in PCr levels observed in the studies discussed reflect a pH-dependent shift in the creatine kinase equilibrium, as suggested by Marini and Nowak (2000), since significant changes in pH were already observed after 6 min of asphyxia, decreasing in parallel in peripheral and brain tissue (Engidawork et al. 2001).

Phospho creatine (PCr) levels in brain, heart and kidneys 10 min after delivery. Survival and PCr levels were measured as indicated in Fig. 3, and according to Ingebretsen’s method, modified by Seidl et al. (2000) to enable concomitant determination of PCr. In control animals, PCr levels were 1.7 ± 0.3; 7 ± 0.1; 8.24 ± 0.2 μmol/g wet wt in brain (n = 7), heart (n = 16) and kidneys (n = 16), respectively, 10 min after caesarean delivery (n = 7). Filled circles survival rate; filled inverted triangles PCr in brain; filled squares PCr in heart; filled triangles PCr in kidneys. Vertical line marks the time (15 min) when survival rate starts to drop; horizontal line marks 50%. pH was measured in parallel (Engidawork et al. 1997, 2001) in peripheral and brain tissue. pH values were 7.36 ± 0.01, and 7.30 ± 0.01, in heart and brain of control caesarean-delivered pups (10 min after delivery); 7.25 ± 0.01 and 7.11 ± 0.01 after 5 min of asphyxia; 7.01 ± 0.02 and 7.05 ± 0.001 after 10 min of asphyxia; 6.9 ± 0.001 and 6.79 ± 0.001 after 15 min of asphyxia, and 6.77 ± 0.01 and 6.55 ± 0.002 after 20 min of asphyxia, in heart and brain, respectively (n = 8–10, per group). Abscissa time (min) of immersion into a water bath at 37°C (asphyxia); ordinate survival in percentage (%). Compared to zero asphyxia

PKC and Cdk activities were measured in heart (Lubec et al. 1997a) and brain (Lubec et al. 1997b), respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, PKC activity was significantly decreased in heart and brain, already following 5 min of perinatal asphyxia. After 15 min of asphyxia, PKC activity was decreased by >90% in both regions. PKC changes following ischaemia/hypoxia have been well studied (see Puceat and Vassort 1996). PKC is involved in several important signalling pathways, modulating ion channel permeability and conductance (Kwank and Jongsma 1996), as well as protein synthesis (see Pain 1986). The observed decrease in PKC activity implies a diminished metabolism, which may protect the animal by diminishing energy requirement.

PKC and Cdk in brain and heart 10 min after delivery. PKC and Cdk activity was measured according Lubec et al. 1997a, b. In control animals, PKC activity was 401.63 ± 26.08, and 109.64 ± 26.65 U/g, in brain (n = 8) and heart (n = 8) 10 min after caesarean delivery, respectively. Cdk activity was 77.38 ± 6.78, and 37.63 ± 3.93 pMPi/min, in brain (n = 8) and heart (n = 8) 10 min after caesarean deliver, respectively. Filled circles survival rate; filled inverted triangles PKC activity in brain; filled diamonds Cdk activity in brain; filled squares PKC activity in heart; filled triangles Cdk activity in heart. Vertical line marks the time (15 min) when the survival rate starts to drop; horizontal line marks 50%. Abscissa time (min) of immersion into a water bath at 37°C (asphyxia); ordinate survival in percentage (%). Compared to zero asphyxia

Cdk activity was decreased in heart, already following mild asphyxia (5–10 min). In brain, Cdk activity paralleled the rate of survival. Indeed, in brain, Cdk levels started to decreased only after 19 min of perinatal asphyxia, to become undetectable after severe asphyxia (20–21 min). Since Cdk is involved in mitosis and proliferation (Doree and Galas 1994), a decrease in Cdk activity implies interruption of replication and differentiation (Lubec et al. 1997b), also for diminishing energy requirements. However, as shown by Fig. 5, it is tempting to conclude that, compared to what occurred in heart, replication and differentiation was preserved in brain, up to an extreme hypoxic condition. In terms of net activity (pMPi/min), Cdk activity in brain (77.38 ± 6.78 pMPi/min; n = 8) (Lubec et al. 1997b) was twice that found in heart (37.43 ± 5.85 pMPi/min; n = 9) (Lubec et al. 1997a) in caesarean-control rats, 10 min after delivery, indicating a higher mitogenic activity in brain than in heart at birth. There is evidence that cell death after brain ischaemia is associated with upregulation and activation of Cdk (Love 2003), and that inhibition of Cdk reduces neuronal loss after brain ischaemia, in vivo or in vitro, suggesting that activation of Cdk plays a role in post-ischaemic neuronal death (Katchanov et al. 2001; Morris et al. 2001).

No evidence has been found for the involvement of ROS, radical adduct and/or antioxidant enzymes when evaluated 10 min after delivery (Lubec et al. 1997a), suggesting that reactive oxygen species may not be relevant in this model. Nevertheless, brain glutamate and lactate levels are significantly increased (>2-fold) when measured 40–80 min after birth by in vivo microdialysis, both in periphery (Engidawork et al. 1997) and brain (Chen et al. 1997a), correlating with a decrease of pH, suggesting a delayed oxidative stress elicited by the re-oxygenation period.

Cell death was evaluated in the frontal neocortex, 10 and 40 min after delivery, using an ELISA kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Cat. No. 1544 675), quantifying histone-associated DNA fragments in the cytoplasmic fraction of cell lysates by spectrophotometry (405 nm). The presence of mono- and oligonucleosomes has been considered as a feature of cells undergoing apoptosis (Bonfocco et al. 1995). However, it cannot be excluded that it also represents a caspase-3 independent cell death. Indeed, using cleaved caspase-3, as a marker for caspase-dependent apoptosis, and 150 kDa calpain-dependent cleavage of α-fodrin, as a marker for necrosis, Ginet et al. (2009) showed an increase of the 150-kDa α-fodrin product in neocortex of rat, 30 min to 24 h after a hypoxic–ischaemic insult at P7, while, in the same preparation, activation of caspase-3 levels started to increase weakly at 6 h, reaching a maximum at 24 h. Figure 6 shows that cell death could be monitored in the frontal cortex of pups 10 min after delivery, which was significantly increased after 10 min of asphyxia, reaching a maximum after 21 min of asphyxia. A parallel but less pronounced effect was observed 40 min after delivery.

Early and delayed cell death in neocortex of asphyxia-exposed and control rat neonates. Early cell death was measured with an ELISA kit quantifying histone-associated DNA fragments in a cytosolic fraction (arbitrary units) 10 (filled circles) and 40 (filled squares) min after delivery (Lubec et al. 1997a). Nuclear fragmentation (number of fragmented nuclei), as an indication of delayed cell death was assayed with haematoxylin–eosin histochemistry, 1–8 days after delivery (filled triangles) (Dell’Anna et al. 1997). Abscissa time (min) of immersion into a water bath at 37°C (asphyxia); ordinate survival in percentage (%). Compared to zero asphyxia

Interestingly, no sign of apoptosis could be observed with haematoxylin–eosin histochemistry up to P8. At P8, nuclear fragmentation could be quantified, and correlated with the length of the insult (Dell’Anna et al. 1997; Lubec et al. 1997a). A significant increase of nuclear fragmentation was already observed after mild insults, when the rate of survival was still 100%. This is a very important observation because it shows delayed cell death occurring when clinical parameters indicate a rather benign condition, an issue recently discussed by Odd et al. (2009).

Organotypic cultures

The model of perinatal asphyxia allows short- and long-term observations in the same experimental series. It also allows performance of in vitro studies for investigating particular issues elicited by the insult. Thus, caesarean-delivered control and asphyxia-exposed animals can be used for preparing organotypic cultures to study neurocircuitry development in vitro. The organotypic culture model moves the pattern of innervation to an earlier stage, forcing neurites to seek the corresponding tissue and cell targets, until innervation plexuses are established (Plenz et al. 1998; Gomez-Urquijo et al. 1999, Morales et al. 2003; Klawitter et al. 2007). Thus, the model makes it possible to specifically investigate the effect of perinatal asphyxia on postnatal neuritogenesis. In organotypic cultures from asphyxia-exposed rats, we found a decrease in the number of secondary to higher level branching of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive neurites (Morales et al. 2003; Klawitter et al. 2005), illustrating the vulnerability of the dopaminergic systems to perinatal asphyxia (Fig. 7).

Neurite atrophy induced by perinatal asphyxia. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive neurons in triple organotypic cultures at 21 days in vitro (DIV) from control (a) and asphyxia-exposed (20 min, at 37°C) (b) pups. The TH immunostaining (BCIP/NBT) was counterstained with fast red for labelling nuclei. The white arrows in a and b indicate the neurons drawn through camera lucida in c and d, respectively. Bars 20 μm (from Morales et al. 2003; with permission)

A regional vulnerability to the long-term effects elicited by perinatal asphyxia has been reported by several laboratories, affecting dopaminergic (Klawitter et al. 2007) and nNOS neuronal systems (Ezquer et al. 2006; Jiang et al. 1997; Capani et al. 1997; Loidl et al. 1997). With the organotypic culture model, we demonstrated that the number and neurite trees of nNOS positive neurons in neostriatum are decreased by perinatal asphyxia, while in the substantia nigra there is a paradoxical increase in the number of nNOS positive neurons (Klawitter et al. 2006, 2007), further underpinning region specific differences observed in the interactions established between dopamine and nNOS neurons in mesencephalon and telencephalon (Gomez-Urquijo et al. 1999; Herrera-Marschitz et al. 2000).

Apoptosis and neurogenesis after perinatal asphyxia

The neurocircuitries of the hippocampus are also vulnerable to hypoxic/ischaemic insults. Using nuclear Hoechst staining and DNA fragmentation assayed by a TUNEL detection kit (NeuroTACS, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), we demonstrated that perinatal asphyxia increases apoptosis in the hippocampus (Morales et al. 2008), as previously suggested (Dell’Anna et al. 1997). An increase of apoptotic nuclei was observed in CA1, CA3 region and supra- and infrapyramidal bands of the hippocampus at P7, and even at P30. That effect was accompanied by an increase in the levels of the pro-apoptotic protein BAD measured by western blots of hippocampal extracts from asphyxia-exposed and control animals. Interestingly, the levels of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 and bFGF were concomitantly increased, suggesting a functional recovery promoted via the MAPK/ERK pathway (Morales et al. 2008). Indeed, we have recently found that phosphorylated ERK-1, and FLRT-3 levels are increased following perinatal asphyxia, as well as the levels of the inhibitory modulator Spry (Tsang and Dawid 2004; Cabrita et al. 2006), suggesting that these proteins also play a role during postnatal stages (Cárdenas et al. 2009).

We have found that the increase of apoptotic like nuclei is particularly remarkable in CA3, in contrast to the observation that more apoptotic cells are seen in CA1 than in CA3 region following hypoxia/ischaemia at P7 (Nakajima et al. 2000; Kawamura et al. 2005). It has been recently reported that the main type of cell death seen in CA3 is by autophagy, but not in CA1, where apoptosis predominates following hypoxia/ischaemia at P7 (Ginet et al. 2009). Using immunocytochemistry against LC3, a protein involved in autophagosome formation, the authors reported an increase of the number of LC3 positive dots in CA3, already 6 h after the hypoxic/ischaemic insult in the cytosol of cells positive for the neuronal marker NeuN. However, the number of punctate LC3-positive neurons decreased at 48 and 72 h (Ginet et al. 2009).

Postnatal neurogenesis has been investigated in the hippocampus of asphyxia-exposed rats, labelled with the thymidine analogue 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU). A significant increase of mitotic activity has been observed, both in brain tissue and organotypic cultures from asphyxia-exposed animals, mainly localized in the DG (Morales et al. 2005, 2007). Only 25% of the new cells co-expressed MAP-2, suggesting proliferation of other types of cells, including astrocytes, microglia, as well as fibroblasts.

In recent studies on neurogenesis with organotypic cultures from the SVZ, we have observed an increase of BrdU/MAP-2 positive cells in cultures from asphyxia-exposed animals (Espina-Marchant et al. 2009). The studies on neurogenesis occurring in the SVZ are interesting, because they could reveal mechanisms for neuronal repair of the adjacent neostriatum. We are also exploring the idea that neurogenesis in the DG of the hippocampus and SVZ is modulated by dopamine terminals from the mesencephalon, which is an attractive hypothesis that provides an explanation for the paradoxical effect of methylphenidate (Ritalin®), used for children suffering from attention deficit syndrome (ADS). Dopamine is perhaps needed for inducing neurogenesis in DG and SVZ, promoting neuronal plasticity, as suggested for Ritalin treated children (see Grund et al. 2006; Schaeferd et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2009; also see Banerjee et al. 2009; Ruocco et al. 2010). The idea is to further investigate the receptors involved in this mechanism, to suggest the use of selective dopamine agonists to treat ADS like syndromes.

Behavioural and cognitive deficits

Motor and cognitive alterations of variable severity, including cerebral palsy, seizures, spasticity, ADS, hyperactivity, mental retardation and/or neuropsychiatric syndromes with delayed clinical onset have been associated with perinatal asphyxia (du Plessis and Volpe 2002; Van Erp et al. 2002; Kaufman et al. 2003; Vannuci and Hagberg 2004; de Hann et al. 2006; Odd et al. 2009). In the rat, several studies have investigated the behavioural effects associated with perinatal asphyxia, addressing motor function (Bjelke et al. 1991; Chen et al. 1995), emotional behaviour (Dell’Anna et al. 1991, Hoeger et al. 2000; Venerosi et al. 2004, 2006, Simola et al. 2008; Morales et al. 2010), and spatial memory (Boksa et al. 1995; Iuvone et al. 1996; Hoeger et al. 2000, 2006; Loidl et al. 2000; Van de Berg et al. 2003; Venerosi et al. 2004).

We have investigated whether perinatal asphyxia may produce long-term effects on cognitive performance, using a behavioural test applied under ethological-like conditions, devoid of any stressful cues or primary reinforcers, such as swimming, food deprivation or electric shocks (Ennaceur and Delacour 1988). The test consists of discriminating between objects differing in shape and colour, without any genuine significance to the rat, or being previously associated with any rewarding or aversive stimuli. During the first session, two copies of the same object are presented to the rat for 4 min, and then again, during the second session, when one of the previously presented objects is replaced by a novel one, similar in size, but different in shape and/or colour. The idea is that the rat has to recognize the novel object, spending longer time exploring the novel than that previously presented. The first and the second sessions can be separated by different time intervals, for evaluating the consolidation of learning. A good memory would be able to recognize a previously presented object after a long time elapsing between a first and second session, meaning that the animal would concentrate on exploring the novel object. In our studies, we used a 15 or 60 min interval, and the animals were studied at 3 months of age (Simola et al. 2008). As shown in Fig. 8, no differences were observed between asphyxia-exposed (20 min asphyxia) and control animals when a 15-min interval elapsed between the first and the second session. Both asphyxia-exposed and control rats recognized the novel stimulus similarly well, spending longer time exploring the novel object. However, when 60 min elapsed between the first and second session, asphyxia-exposed animals spent less time exploring the novel object, indicating that asphyxia-exposed rats could not recognize its novelty. Conversely, asphyxia-exposed rats could not remember that the object was already presented during the first session. This is a straightforward experiment showing a subtle consequence of a metabolic insult (anoxia) occurring at birth, impairing a cognitive function that will show up only after a proper challenge. It is very much reminiscent to the clinical experience revealing effects only when the child starts primary school (see Odd et al. 2009; Strackx et al. 2010).

Effect of perinatal asphyxia on object recognition assessed 3 months after delivery. Asphyxia-exposed (20 min, at 37°C) and control rats recognized similarly well a previously experienced object whenever a 15 min period elapsed between a first-learning and a second-test session. However, asphyxia-exposed animals failed to recognize a previously experienced object whether the period between the first and second session was extended to 60 min. * P < 0.05 (n = 13–18) (from Simola et al. 2008, with permission)

Therapeutic strategies

Hypothermia

In the clinical scenario, after resuscitation of an infant with birth asphyxia, the emphasis is on supportive therapy, although only few ideas exist for preventing, or even reversing the neurotoxic cascade elicited by hypoxia (see Volpe 2001; du Plessis and Volpe 2002). Hypothermia has been pointed out to be an effective intervention to attenuate the secondary neuronal injury elicited by hypoxia (see Engidawork et al. 2001). Although there is still concern for a narrow therapeutic window (Engidawork et al. 2001) and for a lack of a clear mechanism of action for the effect of hypothermia (Herrera-Marschitz et al. 1993, 1994; see Gluckman et al. 2005; Hoeger et al. 2006; Groenendaal and Brouwer 2009; Edwards 2009), there are already several multicentre trial initiatives on this strategy (Gunn and Thoressen 2006). There are several recent excellent reviews about the new strategies for cooling the brain of human babies who suffer asphyxia during birth (Shankaran Shankaran 2009; Groenendaal and Brouwer 2009), including a very insightful review discussing the effect of hypothermia on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters of drug regimes used in neonatology (van den Broek et al. 2010).

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide has been proposed to protect against oxidative stress (Yan et al. 1999; Wan et al. 1999), ischaemic injury (Sakakibara et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2002) and inflammation (Ducrocq et al. 2000) in neonatal rat brain by replacing NADH/NAD+ (Zhang et al. 1995). We have reported (Bustamante et al. 2003) that nicotinamide prevents several of the changes induced by perinatal asphyxia on monoamine contents, even if the treatment was delayed for 24 h, suggesting a clinically relevant therapeutic window. We have later confirmed that observation, reporting that neonatal treatment with nicotinamide prevents the long-term effect of perinatal asphyxia on dopamine release monitored with in vivo microdialysis three months after birth (Bustamante et al. 2007). These findings support the idea that nicotinamide can constitute a therapeutic strategy against the long-term deleterious consequences of perinatal asphyxia, as already proposed for several other pathophysiological conditions (see Virag and Szabo 2002). Nevertheless, the mechanisms explaining the protection provided by nicotinamide have to be further investigated, including histone deacetylation, a mechanism proposed for the recent introduction of nicotinamide as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and other taupathies (Green et al. 2008).

Ultrapotent novel PARP-1 inhibitors

The PARP-1 inhibitory action of nicotinamide is well established (see Virag and Szabo 2002). We have observed that therapeutic doses of nicotinamide (0.8 mmol/kg, i.p.) produced a long-lasting inhibition of PARP-1 activity measured in brain and heart from asphyxia-exposed and control animals (Allende et al. 2009). As shown in Fig. 9, a significant inhibition of PARP-1 activity in heart and brain was observed 1 and 8 h after a single dose of nicotinamide.

Effect of nicotinamide on PARP-1 activity in brain and heart from asphyxia-exposed and control rat neonates. PARP-1 activity was measured by a PARP Universal Colorimetric Assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; catalogue #4677-096-K) in heart (a, b) and brain (c, d) and tissue dissected from asphyxia-exposed (AS, n = 5; AN, n = 5) and control (CS, n = 5; CN, n = 5) animals, treated with saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) (AS, CS), or nicotinamide (0.8 mmol/kg, i.p.) (CN, AN) 1 h after delivery. The animals were dissected 1 h or 8 h after a single administration of saline or nicotinamide. Open and grey columns PARP-1 activity in CS and AS pups, respectively. Dashed columns PARP-1 activity in CN and AN pups, respectively. * P < 0.05 (Allende et al. in preparation)

The use of nicotinamide has been challenged because of its low potency, limited cell uptake and short cell viability, stimulating the search for more specific compounds, such as 3-aminobenzamide (Ducrocq et al. 2000; Hortobagyi et al. 2003; Koh et al. 2004); 3,4-dihydro-5-[4-(1-piperidinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone (DPQ) (Takahashi et al. 1999); PJ34 (Abdelkarim et al. 2001); N-3-(4-Oxo-3,4-dihydrophthalazin-1-yl)phenyl-4-(morpholin-4-yl) butanamide methane sulphonate monohydrate (ONO-1924H) (Kamanaka et al. 2004); 5-chloro-2-[3-(4-phenyl-3,6-dihydro-1(2H)-pyridinyl) propyl]-4(3H)-quinazoline (FR247304) (Iwashita et al. 2004); and 2-methyl-3,5,7,8-tetrahydrothiopyranol[4,3-d]pyrimidine-4-one] (DR2313) (Nakajima et al. 2005). Ultrapotent novel PARP inhibitors are now entering human clinical trials for reducing parenchymal cell necrosis following stroke and/or myocardial infarction, down-regulating multiple pathways of inflammation and tissue injury following circulatory shock, colitis or diabetic complications (Jagtap and Szabo 2005).

Ultrapotent versus weak PARP-1 inhibitors: new versus old molecules

There is, however, concern about applying ultrapotent PARP-1 inhibitors during development, since it has been shown that PARP-1 is required for efficient repair of damaged DNA (Trucco et al. 1998; Schultz et al. 2003). Therefore, it has been suggested that moderate PARP-1 inhibitors should be chosen for neuronal protection, whenever used for paediatric patients (Moonen et al. 2005; Geraets et al. 2006). Several naturally occurring compounds have been suggested to inhibit PARP-1 over-activation. Caffeine metabolites, but not caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) itself, are inhibitors of PARP-1 at physiological concentrations (Geraets et al. 2006). Theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine) is an interesting candidate to be investigated, because it already has a clinical application for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in children (Moonen et al. 2005). The most attractive compound is, however, paraxanthine (1,7-dimethylxanthine) (Geraets et al. 2006), the major metabolite of caffeine in humans, whose clinical potential we already proposed at the beginning of the 1990s (Ferre et al. 1991).

Nicotinamide is still an interesting molecule because of its low potency, which can be an advantage when used for developing animals, antagonizing the effects elicited by PARP-1 overactivation without impairing DNA repair or cell proliferation. Nicotinamide has been proposed as an agent against oxidative stress (Yan et al. 1999; Wan et al. 1999), and its pharmacodynamic properties can provide advantages over more selective compounds. Furthermore, nicotinamide has already been tested in human clinical trials without showing any significant toxicity, although its therapeutic efficacy is still controversial (Macleod et al. 2004). Nicotinamide can constitute a lead for exploring compounds with similar or better pharmacological profiles. We are particularly interested in testing the substituted benzamide N-(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinylmethyl)-2-methoxy-5-sulphamoyl benzamide (Sulpiden®, and other benzamides of clinical use in paediatrics); and the xanthine analogs, 1,3-dimethylxanthine and 1,7-dimethylxanthine, substances already used for different clinical applications.

PARP-1 is still a relatively novel therapeutic target. Putative PARP-1-inhibitory substances should be systematically characterized, evaluating their potential as drugs for paediatric use.

Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenetics and beyond: levels for molecular network interactions

The above described pivotal role of the PARP family of transcription factors in perinatal hypoxic conditions with long-lasting consequences on brain development and tentative deficits of decisive brain functions brings up the question of the molecular mechanisms affected by the specific environmental impact via gene transcription. Very likely, a host of molecular interactions is disturbed by such a profound impact at a critical time period of life (Bertrand et al. 2007).

Gene transcription may be affected by modifications of methylation patterns of various gene promoters or changes of histone methylations/acetylations or additional modifications. These events are particularly vulnerable to environmental influences. Moreover, they can be long-lasting and even be inherited.

At this level, it is intriguing, as well, to turn the view to transcription factors, because they are at the core of regulation of whole molecular networks; of their compositions, as well as activities. Not only PARPs, but also hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), AIF (see Acker and Acker 2004), and other factors known to be affected by hypoxic conditions, regulate the transcription of specific arrays of genes with respective responsive elements in their promoters (Fig. 10).

Transcription factor-dependent molecular networks. Three molecular levels are displayed in the figure. Transcription factors control transcription of sets of genes specific for each factor at the DNA level (DNA and histone modifications, which are also involved in regulation of gene transcription are omitted). This concerted action is fine-tuned on the transcript level by various mRNA processing events (alternative splicing, editing, etc., not shown). Then the transcripts (here 1–10) are translated into proteins (1–10; within circles) that fulfil their tasks within large molecular networks by interaction with specific partner molecules. Because of the influence of one transcription factor on the expression of several proteins, only subtle disturbances on the DNA level may have substantial effects on the complex molecular networks on the protein level. Often, the complete set of genes controlled by a given transcription factor is not known. Therefore, the array in the protein network (as shown here, for example, 3 genes for PARP1 and AIF, and 2 genes for HIF and p300) belonging to these factors is incomplete. Furthermore, even though there would be a complete picture of some transcription factors on the protein level, activities of proteins with significant functions, i.e. not belonging to the genes regulated by the given transcription factors, may be compromised by the altered concentrations (activities) of the proteins belonging to the given transcription factor regulated genes. An assessment of these complex interactions is not possible by human intuition, but is feasible by computer simulations based on intelligent software programs. Mathematical simulations of the behaviour of those protein networks can help to identify nodes critical for overall network functioning, and may even predict consequences of network disturbances (see Matthäus et al. 2010). PARP-1, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; HIF-1, hypoxia inducible factor; AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; p300, Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator

For clarity purpose, Fig. 10 only shows effects of a few transcription factors on two or three genes (instead of dozens). Each gene can give rise to several gene products (proteins) by alternative splicing, multiple start codons, etc. The gene products then interact with each other in well-balanced molecular networks (Ooi and Wood 2008). Evidently, disturbances of expression or function of only one transcription factor affects the expression of many genes and of their gene products, and have unpredictable consequences on the dynamics of the molecular networks. Such disturbances can be compared with wave-like bursts originating from multiple sources and interfering with the above-balanced molecular activity oscillations. Eventually, the outcome depends on the ‘buffering’ capacity of those oscillatory networks. The observations following hypoxic conditions, as outlined above, rather speak to insufficient buffering capacity, which results in stronger or weaker overshoot reactions. Consequences may be acute and dramatic, with cell death and tissue damage, or milder, but with long-lasting and subtle deficits of brain function.

It is a huge challenge in molecular biology to understand control and regulation of gene expression including all the feedback mechanisms between proteins and genes, and between genes and the environment. We need to obtain more thorough insights into these intricate and very dynamic events occurring on these different levels. The task is to understand Fig. 10, completed by dozens of transcription factors with hundreds or thousands of genes controlled by combinations of those factors, and completed on the protein network level by many more proteins that keep interacting in self-sustained, but also exogenously influenced actions. The task of understanding such a complex molecular system is bewildering. However, there is hope that computers equipped with smart programs can help to unravel and visualize those sophisticated molecular systems. Much is known about the biochemistry of proteins, metabolic interactions or signalling pathways. Many of those data could be inserted into mathematical algorithms, using graph-theoretical approaches (Abul-Husn et al. 2009; Lipshtat et al. 2009), Petri nets (Wu and Voit 2009) or ordinary and non-linear differential equations (Ho et al. 2007). Differential equations are probably the most comprehensible way to characterize and deal with the dynamic behaviour of molecular networks. Because, however, for each node (molecule) of the network, one equation has to be constructed, their application becomes unfeasible with the number of nodes to be described. The present computational power reaches its limits when thousand or more of those equations have to be solved.

An option that has been used frequently on biological networks, such as on metabolic, protein and gene networks, are scale-free topologies (Matthäus et al. 2010). They can be distinguished into four classes of graphs which are very useful for biological applications: (i) regular; (ii) random; (iii) ‘small-world’, and (iv) scale-free graphs. It is one of the major findings of the last decade of intense studies of biological networks, that scale-free graphs are able to represent the topology of such networks more accurately than other types of random graphs (McGarry et al. 2007). The strength of graph theory is that it can represent a complex system in a unified formal language of nodes and links. Strictly speaking, a graph representation of metabolism consists of two types of nodes, metabolites and enzymes, where either the metabolites or the enzymes are the nodes. This system is described by flux-balance-analysis (FBA), which is a widely accepted method for in silico studies of metabolic states (Oberhardt et al. 2009; Feala et al. 2009). Its severe limitation, it only describes steady states, has been refined by the incorporation of temporal and gene regulatory information.

In terms of enzymes, the internal dynamics of any of these molecules is important. Since typically these dynamics are complex and their details are not well enough known, their operation may be modelled like an automaton. In principle, cellular automata on graphs allow assessing dynamic changes due to variation of graph topology (Kier et al. 2005). Cellular automata on graphs serve to investigate dynamic information storage, as reported for memory storage in brain astrocytes (Caudle 2006), or used as models of pattern formation. Molecular patterns are believed to be characteristic for a disease. These patterns, however, are not static. Graph-theoretical approaches appear to be very useful to animate those patterns and in this way show their changes over time. We think that those kinds of animations are extremely important to obtain major understandings about causes, progression and consequences of chronic diseases.

Relevance and conclusions

The present review addresses an important health problem, with both paediatric and neuropsychiatric implications. A long-term goal is to design new therapeutic strategies for preventing or even treating the effects of perinatal asphyxia, as well as to understand the mechanisms by which early metabolic insults prime the development of the CNS.

It is expected that future study will allow the identification of critical molecular, morphological, physiological and pharmacological parameters, specifying variables that should be considered when planning neonatal care and development programmes.

The pivotal role of the PARP family of transcription factors in perinatal hypoxic conditions with long-lasting consequences on brain development and deficits of decisive brain functions, brings up the question of the molecular mechanisms affected by specific environmental impact via gene transcription. A host of molecular interactions is likely disturbed by such a profound impact at a critical time period of life. Gene transcription may be affected by modifications of methylation patterns of various gene promoters or changes of histone methylations/acetylations or additional modifications. These events are particularly vulnerable to environmental influences; they can be long-lasting and even be inherited.

It is a huge challenge in molecular biology to understand control and regulation of gene expression including all the feedback mechanisms between proteins and genes, and between genes and the environment. We need to obtain more thorough insights into these intricate and dynamic events occurring on these different levels. While nobody will be able to overlook such a kind of complex molecular system, there is hope that computers equipped with smart programs will help to unravel and visualize those sophisticated molecular systems. Mathematicians in bioinformatics, biophysics and related disciplines are working on solutions to identify molecular network and neuronal wiring patterns characteristic for specific brain disorders and to develop tools to simulate dynamic actions of molecules and cells. With these approaches, we hope to learn more about the past development of a disease and to make predictions of its further progression. Ideally, these efforts should give valuable hints of pivotal molecules, cells or neurocircuitries to be addressed by pharmacological measures.

Abbreviations

- AIF:

-

Apoptosis-inducing factor

- ADP:

-

Adenosine diphosphate

- ADS:

-

Attention deficit syndrome

- AMP:

-

Adenosine monophosphate

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAD:

-

Bcl-2-associated death promoter

- bFGF:

-

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- BAX:

-

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BCL-2:

-

B-cell lymphoma-2

- BCL-X:

-

Bcl-2-related gene

- BCL-XL :

-

Bcl-X larger isoform

- BCL-XS :

-

Bcl-X shorter isoform

- BID:

-

BH3 interacting domain death agonist

- BrdU:

-

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CA:

-

Cornus Ammonis

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- Cr:

-

Creatine

- CS:

-

Caesarean-delivered

- Cdk:

-

Cyclin-dependent kinase

- DAPK:

-

Death-associated protein kinase

- DCX:

-

Doublecortin

- DG:

-

Dentate gyrus

- DIV:

-

Days in vitro

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DNMT1:

-

DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1

- DRP-1:

-

Dynamin-related protein

- Elk1:

-

Ets like gene 1

- ERCC2:

-

Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair group 2

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- FBA:

-

Flux-balance-analysis

- FGFR:

-

bFGF receptors

- FLRT3:

-

Fibronectin-leucin-rich transmembrane protein

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylases

- HIF-1:

-

Hypoxia induceble factor-1

- L1:

-

L1CAM cell adhesion molecule

- MAP-2:

-

Microtubule-associated protein-2

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NAD:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADH:

-

Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor κB

- Ngn2:

-

Neurogenin-2

- NgR:

-

Nogo receptor

- nNOS:

-

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- PARG:

-

Poly-(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase

- PARylated PARP:

-

Poly-(ADP-ribosylated) PARP

- PARPs:

-

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases

- PCAF:

-

p300/CBP-associated factor

- PCr:

-

Phospho creatine

- PIP2:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-diphosphate

- PKC:

-

Protein kinase C

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Sef:

-

Similar expression fgf gene

- SIRT:

-

Sirtuin

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- Spry:

-

Sprouty

- SRY:

-

Sex determining region Y

- SVZ:

-

Subventricular zone

- TH:

-

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- Thy-1:

-

THY thymocyte differentiation antigen 1

- TUNEL:

-

TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling

- XRCC1:

-

X-ray Cross Complementing Factor 1

References