Abstract

Purpose

To determine the stated practices of clinicians in weaning critically ill adults from invasive ventilation.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, self-administered postal survey of Critical Care physicians and respiratory therapists (RTs) in leadership roles at Canadian teaching hospitals. We identified respondents using electronic mail and telephone correspondence. We used rigorous survey methodology to develop, test, and administer the questionnaire.

Results

One hundred ten of 162 (67.9%) clinicians returned the survey with 99 respondents (55 physicians and 44 RTs) completing it either in-part or in-full. Approximately 95% of respondents acknowledged ever performing spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs) in clinical practice. Of these, 95.6% and 32% of respondents reported conducting daily and twice-daily screening to identify SBT candidates, at least sometimes. The three most common techniques to conduct SBTs included; pressure support (PS) with positive end-expiratory pressure (70.8%), continuous positive airway pressure (35.7%), and use of a T-piece (25.0%). PS ventilation was the weaning strategy used most frequently before SBTs. Most respondents (57.1%) considered continuous infusion of sedative-hypnotics to be a relative contraindication to tracheal extubation. However, concurrent administration of low dose vasopressors, inotropes, and analgesic boluses, or continuous analgesic infusions were considered acceptable amongst 60.8%, 73.2%, 78.4% and 58.8% of respondents, respectively. We did not observe regional variation in whether clinicians ever perform SBTs, the ventilatory modes used prior to an SBT nor in the use of PS and SBTs during the weaning process.

Conclusions

Pressure support and SBTs are common features of weaning in Canadian teaching hospitals. Compared to the published literature, our survey suggests that weaning practices have evolved over time and that practice variation may be greater on an international level compared to a national level.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer les pratiques déclarées des cliniciens concernant le sevrage des patients adultes gravement malades de la ventilation invasive.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé un sondage transversal, auto-administré et envoyé par courrier auprès des médecins des soins critiques et des inhalothérapeutes occupant des positions de leadership dans les hôpitaux d’enseignement canadiens. Nous avons identifié les répondants à l’aide de correspondance par courrier électronique et par téléphone. Nous avons utilisé une méthodologie de sondage rigoureuse afin d’élaborer, de tester et d’administrer le questionnaire.

Résultats

Sur un total de 162 cliniciens, 110 (67,9%) ont renvoyé le questionnaire; 99 répondants (55 médecins et 44 inhalothérapeutes) ont complété le questionnaire en entier ou en partie. Environ 95 % des répondants ont reconnu qu’ils réalisaient des tests de ventilation spontanée (TVS) dans leur pratique clinique. Parmi ceux-ci, 95,6 % et 32 % des répondants ont affirmé réaliser des dépistages quotidiens ou deux fois par jour pour identifier les candidats potentiels à un TVS, au moins des fois. Les trois techniques les plus fréquentes pour réaliser les TVS étaient : aide inspiratoire (AI) avec pression positive télé-expiratoire (70,8 %), ventilation en pression positive continue (35,7 %), et utilisation d’un tube en T (25,0 %). L’aide inspiratoire était la stratégie de sevrage la plus fréquemment utilisée avec les TVS. La plupart des répondants (57,1 %) ont estimé que la perfusion simultanée d’agents sédatifs hypnotiques constituait une contre-indication relative à l’extubation trachéale. Toutefois, l’administration simultanée de vasopresseurs, d’inotropes et de bolus d’analgésiques en dosage réduit, ou de perfusions analgésiques continues, était considérée comme acceptable par 60,8 %, 73,2 %, 78,4 % et 58,8 % des répondants, respectivement. Nous n’avons pas observé de variations régionales dans la fréquence de dépistage, les modes de ventilation utilisés avant de réaliser un TVS ou l’utilisation d’AI et de TVS pendant le processus de sevrage.

Conclusion

L’AI et les TVS sont des traits communs du sevrage dans les hôpitaux d’enseignement au Canada. Par rapport à la littérature publiée, notre sondage suggère que les pratiques de sevrage ont évolué avec le temps et que les variations de pratique pourraient être plus grandes entre les régions plutôt qu’au sein des régions du Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF) frequently require mechanical ventilation. Life support technology accounts for approximately 5–10% of acute care bed occupancy1 and has been identified as a key factor escalating intensive care unit (ICU) costs.2 Weaning accounts for 41% and 60% of the total ventilatory time in mixed, medical-surgical ICU populations and in populations with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), respectively.3

Over the past decade, clinical investigations have focused on strategies to limit the duration of ventilation, for example, early identification of patients who are likely to be weaned,4–6 tests of readiness to resume spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs),7–9 and strategies to reduce support in patients who fail a SBT.10–12 Several modes and techniques have been used to liberate critically ill adults from invasive mechanical ventilation. The optimal strategy to wean patients from invasive ventilation remains unclear. Compared with traditional care, protocols have been shown to decrease the time to ventilator discontinuation and the total duration of mechanical support.4–6 However, many barriers exist to implementing weaning protocols in clinical practice.13,14

Despite the wide use of mechanical ventilation and the recent proliferation of studies on mechanical ventilation discontinuation strategies, little is known about methods of discontinuing mechanical ventilation in clinical practice. In particular, limited information exists regarding the frequency by which clinicians screen patients to determine their ability to undergo a SBT, the criteria that clinicians used to identify weaning and extubation “readiness”, and the approach clinicians use prior to and during SBT conduct. Our goals were to conduct a self-administered, postal questionnaire to characterize current weaning practices and organizational aspects regarding weaning at adult ICUs in Canada.

Methods

Sampling frame

We conducted a cross-sectional, self-administered survey at Canadian teaching hospitals. We identified Critical Care Site Chiefs and head Respiratory Therapists (RTs) at these hospitals anticipating that individuals in leadership roles would be aware of local weaning policies and have a broad understanding of how critically ill adults are weaned from mechanical ventilation, not only in their personal practices but also in their ICUs. Using telephone and electronic mail correspondence, we identified potential respondents by contacting Critical Care training program directors, teaching hospitals, and colleagues. We obtained mailing addresses from the Canadian Medical Association directory, the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group membership list, and hospital websites. The Research Ethics Board of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto approved this study.

Questionnaire development and formatting

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for relevant evidence pertaining to weaning and tracheal extubation. We identified five content areas of interest (domains), including (1) identification of weaning candidates; (2) conduct of SBTs; (3) preferred methods for adjusting support; (4) tracheal extubation assessment; and (5) other aspects of weaning (including but not limited to sedation titration, use of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV), and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) assessment). Most questions inquired about the practices of individual respondents. We also posed questions to characterize weaning practices in respondents’ ICUs. We developed questions highlighting important issues in weaning and tracheal extubation within each domain.15 Through discussion, two investigators (KB, FL) reduced the number of questions in order to obtain a maximum of five items within core domains. We formatted questions to provide a range of responses exploring weaning practices using nominal, interval, and ordinal responses within domains. We used ordinal response formats (Never [0%], Rarely [1–10%], Infrequently [11–39%], Sometimes [40–60%], Frequently [61–89%], Usually [90–99%], and Always [100%]) to reflect the frequency (percentage of time) with which tasks were performed or techniques were used. We posed five unique questions specifically intended for the RT respondents regarding humidification, the number and type of ventilators available, the frequency with which changes are made to ventilator settings, and the ratio of RTs to patients.

We included instructions at the beginning of the questionnaire to inform respondents that the questions referred to non-tracheostomized patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hr. We defined weaning as “adjusting ventilator support with the goal of removing patients from invasive support during the recovery phase (i.e., after at least partial resolution of the acute illness that precipitated intubation)”, and we defined SBT as “a focused assessment of the patient’s capacity to breathe spontaneously with any one of a number of techniques (i.e., continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], T-piece, and pressure support [PS] with minimal assistance)”. The complete questionnaire included 29 questions. Eight questions specifically addressed practices in the respondent’s ICU, and five questions were completed by RTs alone. The remaining questions reflected respondents’ practices.

Questionnaire testing

We pilot tested the questionnaire to assess comprehensiveness and clarity using semi-structured interviews with two RTs, three Critical Care physicians, and one Research Coordinator.15 We assessed face validity, clarity, and content in a focus group session involving four intensivist–methodologists from Hamilton and Toronto.15 After translating the questionnaire into French, we assessed reliability by administering the questionnaire to eight adult intensivists and eight RTs using six French and ten English questionnaires at three sites (St. Michael’s Hospital, Hopital de l’Enfant Jesus, and the London Health Sciences Centre) on two occasions within about a 2- to 4-wk timespan.

Questionnaire administration

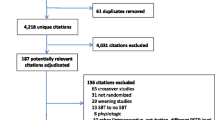

We mailed the questionnaire to all (n = 162) identified potential respondents for personal completion. Non-respondents were sent at least two additional questionnaires. Participation was voluntary and all responses were confidential.

Statistics

As a measure of test–retest reliability, we calculated Cohen’s kappa (κ) for each response option or survey item when responses appeared in tabular format. We considered κ ≥ 0.40 to represent moderate to good agreement. For test–retest reliability, we found 68.6% of all κ scores ≥0.40, suggesting moderate to good agreement on most items. We present descriptive statistics as proportions and either means (±SD) or median (25th, 75th percentile), as appropriate. We collapsed ordinal categories, where appropriate, to enhance clarity. In reporting proportions, we excluded ‘not applicable’ and ‘missing items’ to reflect applicable responses only. We compared proportions using the Chi-square test statistic. We partitioned responses into four regions; i.e., West Coast (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Winnipeg), Ontario, Quebec, and East Coast (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland) to examine the effect of region on the frequency of screening for SBTs, the method of conduct of SBTs, the mode most frequently used before a SBT, and the use of PS and SBTs together during weaning using the Chi square test (alternatively, Fisher’s exact test). We excluded null proportions in analyzing regional variance and considered P-values <0.05 to represent statistical significance.

Results

Respondents

One hundred ten of 162 (67.9%) clinicians responded with 99 respondents (55 physicians and 44 RTs) completing the survey in-part or in-full (Table 1). Whereas Critical Care leaders referred to medical-surgical, neurosurgical, and multidisciplinary ICUs when completing the survey, head RTs referred to more diverse locations, including medical-surgical, multidisciplinary ICUs, and coronary care units, as well as cardiovascular, medical, surgical, trauma, and neurosurgical ICUs. Physician respondents held certifications in Emergency Medicine (1.9%), Cardiology (3.8%), Surgery (9.4%), Anesthesia (30.2%), Respirology (34.0%), Internal Medicine (45.3%), and Critical Care (77.8%).

Mechanical ventilation discontinuation practices

Screening for the ability to undergo trials of spontaneous breathing

While 95.6% of applicable respondents reported screening patients once daily, at least sometimes (40–60% of the time), for the ability to undergo a SBT, only 32% of respondents stated that they conduct twice daily screening with similar frequency (Fig. 1). The majority of respondents considered a maximal fractional concentration of oxygen (FiO2) threshold of 41–50% (64.8%), a minimum arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) threshold of 91–93% (61.2%), and a maximum positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 7–9 cm H2O (48.3%) in assessing SBT readiness. Regardless of the type of humidification used (Heat and Moisture Exchanger [HME] 38.5% or Heated Humidification [HH] 30.9%), respondents most frequently reported using a threshold PS level of 9–12 cm H2O in contemplating SBT readiness. Approximately 17% of respondents reported using a PS level as low as 5–8 cm H2O in identifying SBT candidates.

Respondents most commonly use maximum respiratory rates (RR) of 29–34 breaths · min−1 (33.0%) or 23–28 breaths · min−1 (31.9%) in deciding SBT candidacy. While 36.0% of respondents use a minimum GCS of 12–14, 31.4% of respondents reported using a GCS of 9–11 in considering SBT readiness. Most commonly, respondents report using maximum minute ventilation (V E) of either 14–15 L · min−1 (28.9%) or 12–13 L · min−1 (25.6%) and a rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI) of ≤105 (52.2%) to identify SBT candidates. With the exception of RR (8.8%), we found that minimum GCS (26.7%), maximum tolerated Norepinephrine dose (28.1%), V E (31.1%), and RSBI (29.3%) either were not used or were not considered by respondents in decision-making in this regard. Most respondents either did not use or did not consider the minimum forced vital capacity (67.4%), negative inspiratory force (52.2%), or maximum expiratory pressure (94.6%) to identify SBT candidates. The majority of respondents (30.3%) considered low-dose vasopressors (0.01–0.07 μg · kg−1 · min−1 Norepinephrine or equivalent) as a maximum threshold in assessing SBT eligibility. While 18.0% of respondents reported considering SBT readiness with moderate dose vasopressors (0.08–0.14 μg · kg−1 · min−1 of Norepinephrine or equivalent), 20.2% of respondents only considered an SBT in patients not requiring vasopressors.

Spontaneous breathing trials

Approximately 95% of respondents acknowledged ever performing SBTs in clinical practice. Respondents reported primarily using three techniques ‘at least sometimes’ in conducting SBTs; PS with PEEP (70.8%), CPAP without PS (35.7%), and T-piece without CPAP (25.0%). A minority of respondents conduct SBTs using PS without PEEP (9.4%) and T-piece with CPAP (8.5%), at least sometimes. With regard to levels of PS used during SBTs, the majority of respondents reported using PS 5–7 cm H2O with HME and HH for SBTs (74.3% and 77.1%, respectively). A PS level of 8–10 cm H2O was infrequently used during SBTs conducted with HME (18.6%) or HH (15.7%). Respondents using CPAP for SBTs predominantly use levels of 5–7 cm H2O (86.1%), with and without PS.

Modes of ventilation

Respondents reported using PS (85.3%) most frequently or at least sometimes (96.9%) prior to a SBT. A minority reported using other modes before a SBT, including synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) with PS, volume Assist Control (AC), and pressure-limited modes with volume guarantee (PLVG) (Fig. 2). Prior to a SBT, clinicians infrequently reported using SIMV with PS (22.7%), PLVG (18.9%), and volume AC (16.7%) and rarely reported using pressure AC (8.4%), automatic tube compensation (7.5%), and SIMV without PS (1.1%). The majority of respondents reported that they gradually decrease the level of PS and conduct SBTs (77.9%) rather than gradually reducing the level of PS without conducting SBTs (40.9%) or maintaining a constant level of PS, while conducting SBTs (32.6%), at least sometimes.

Tracheal extubation assessment

The majority of respondents reported considering the presence of a cuff leak on inspiration and expiration (34.0%), a level of consciousness consistent with a Sedation Agitation Scale score16 of 3 (45.5%), a gag reflex (48.5%) and cough of moderate strength (75.8%), and a suctioning frequency of q 2–3 hr (as indicated by secretion volume) (39.2%) in assessing extubation readiness. Except for assessments of level of consciousness (2.0%) and cough strength (6.1%), assessments of cuff leak (26.8%), gag reflex strength (35.1%), and suctioning frequency (19.6%) either were not used or were not considered by many respondents in determining extubation readiness. Compared with non-brain-injured patients, more respondents considered the GCS score, at least sometimes, when assessing brain-injured patients for tracheal extubation (60.8% vs 75.8%, P < 0.05).

While most respondents considered continuous sedative infusions (57.1%) to be a relative contraindication to tracheal extubation, 68.4%, 78.4%, and 58.8% of respondents did not consider intermittent sedative, intermittent analgesic boluses, or continuous analgesic infusions to be contraindications to tracheal extubation, respectively. Most respondents did not consider low-dose vasopressors (≤0.1 μg · kg−1 · min−1 Norepinephrine [60.8%], and inotropes [73.2%]) as contraindications. However, 36.1% and 24.7% of respondents considered low-dose vasopressors and inotropes, respectively, to represent relative contraindications to tracheal extubation. While most respondents considered brain-injured (61.1%) and non-brain-injured patients (65.3%), who arise to stimuli and localize pain but not obey commands, to have a relative contraindication to tracheal extubation, approximately 25% of respondents did not consider this constellation of features to be a contraindication. In Table 2, we summarize respondents’ responses regarding whether patients under their care would be extubated after hours (19:00–07:00 hr) following a successful SBT and assuming few concerns surrounding extubation readiness.

Other aspects of weaning

We posed several additional questions to highlight the presence of written directives (guideline, protocol, or policy) for the conduct of SBTs and weaning and to elucidate roles played by various health care providers in several aspects of weaning and tracheal extubation. Written guidelines, protocols, or policies for the conduct of SBTs and to guide weaning were present in 62.9% and 47.9% of respondents’ ICUs, respectively. The SBT techniques most frequently recommended by the written directive for SBT conduct included PS with PEEP (62.7%), CPAP without PS (28.8%), and T-piece without CPAP (23.7%). While no mode of ventilation was specified in 22.2% of medical directives for weaning, PS (68.9%) and SIMV plus PS (26.7%) were the most frequently recommended modes in ICUs with a weaning directive.

Table 3 shows the roles performed by health care providers in weaning and tracheal extubation in Canada. In Table 4, the use of NIV is summarized during weaning and in the post-extubation period. While several respondents reported not having used NIV during weaning or prophylactically in high-risk patients following tracheal extubation, it is particularly interesting that only 2% of respondents never use NIV for post-extubation respiratory failure. Moreover, respondents reported using NIV for post-extubation respiratory failure in diverse patients, including those with COPD (86.9%), obesity ± obstructive sleep apnea (79.8%), cardiogenic pulmonary edema (73.7%), and in postoperative (69.7%) and immunocompromised (38.4%) patients.

With regard to sedation scale use and GCS computation, 62.6% of respondents acknowledged having a written directive for sedation administration in their ICU. However, 15.2% of respondents were uncertain as to whether a written directive existed to guide sedation administration in their ICUs. Three sedation scale scores [Ramsay17 (27.2%), Sedation Agitation Scale Score16 (25.0%) and the Richmond Agitation Scale Score18 (20.7%)] are most frequently used in our ICUs. Most respondents reported disregarding the verbal component of the GCS (24.7%), assigning a verbal score of 1 (15.5%), or prioritizing verbal scores of 1, 3, and 5 (14.4%) in computing the GCS. Twenty-nine percent of respondents confirmed that they do not calculate the GCS.

Respiratory therapists reported using HH (47.7%) more often than using HME (22.7%) or an equal combination of humidification systems (29.5%). On average, RTs titrate PS 3.7 ± 1.4 times (median: 3) from 7:00 am to 7:00 pm and 1.8 ± 1.1 times (median: 2) from 7:00 pm to 7:00 am and RR 1.7 ± 2.1 times (median: 1) and 1.4 ± 1.0 times (median: 1) during day and night shifts, respectively.

Regional variation in weaning practices

We identified significant regional variation in the frequency of screening more than twice daily (P = 0.047) and in the use of CPAP (without PS) to conduct SBTs (P < 0.0005) (Table 5). We did not find differences among regions in whether clinicians ever perform SBTs, in how PS and SBTs are used in combination during weaning, and in the modes of ventilation used (and most frequently used) prior to an SBT.

Discussion

Our survey of RT and Critical Care leaders identified several consistent practices in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Over 95% of respondents reported conducting once daily screening to identify SBT candidates, at least sometimes, in their ICUs. Additionally, SBTs are conducted most frequently using three techniques; PS with PEEP, CPAP (without PS), and T-piece. PS was the most frequently used mode of ventilation prior to a SBT, with the majority of respondents acknowledging a preference to gradually reduce PS and conduct SBTs, rather than reducing PS without conducting SBTs or maintaining constant PS and conducting SBTs. Most respondents did not consider low-dose vasopressors or inotropes as contraindications to tracheal extubation. While continuous sedative infusions were considered a relative contraindication to tracheal extubation by our respondents, intermittent sedative and analgesic boluses and continuous analgesic infusions were not regarded as contraindications to tracheal extubation. During weaning and in the post-extubation period, we noted practice variation in sedation titration, GCS measurement, and NIV use.

Previous research in this area of critical care practice is limited. Using a one-page self-administered questionnaire, Venus et al. 19 surveyed hospital-based Respiratory Care Departments in the United States in the mid 1980s. The authors found that intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) was the most commonly used mode of ventilation (71.6%) and the most frequently used weaning technique (90.2%). In this survey, respondents reported that IMV was frequently transitioned to CPAP (26.4%) or T-piece (63.8%). Nearly a decade later, in a 1-day, cross-sectional study involving 290 patients mechanically ventilated for at least 24 hr in 47 medical surgical ICUs in Spain, Esteban et al. found that a broader array of techniques, including T-piece trials (24%), SIMV (18%), PS (15%), SIMV plus PS (9%), and a combination of methods (33%) were used during weaning.3 In contrast to our findings, patients in this study were supported using either AC (55%) or SIMV (26%), and few were managed with PS (8%). In a subsequent observational study involving 5,131 patients in 20 countries, Esteban et al. 20 found that once-daily or multiple daily weaning trials were used in 77.8% and 14.0% of weaning attempts. The authors observed that gradual reductions in PS with SIMV, PS or SIMV were utilized in 21.8%, 20.7% and 8.5% of weaning attempts, respectively, and weaning trials were predominantly conducted using T-piece (51.6%), PS (28.2%), and CPAP (19.2%).

Several observations can be made in comparing our survey results with those of prior publications. First, we note a trend away from the use of IMV and SIMV during discontinuation of mechanical ventilation. This trend likely reflects the temporal development of pressure-limited modes of ventilation and concerns regarding the potential for IMV to increase work of breathing.21 Second, unlike the initial Esteban study3 wherein patients were predominantly supported using AC (a volume-limited mode), our respondents reported preferential use of PS (a pressure-limited mode) prior to SBTs. Whereas Esteban found a high use of once-daily SBTs during weaning, our respondents preferred to gradually reduce the level of PS while intermittently conducting SBTs during weaning. This raises the possibility that clinicians may approach weaning differently by using different modes of initial support and conducting SBTs with different intent and timing. Whereas clinicians who use volume-limited ventilation prior to a SBT manually titrate V T and RR, clinicians who use pressure-limited ventilation permit patients to auto-titrate these parameters. As a result, clinicians using volume ventilation may use SBTs as a “process of discovery”,3 while those using pressure ventilation may conduct SBTs as a “pre-separation technique”. It remains to be determined whether the alternative approaches liberate patients who use comparable techniques at similar or different time points during weaning. Third, in contrast to the findings of Esteban et al., 20 our respondents preferred to conduct SBTs with techniques that permit adding low levels of PEEP. Use of a T-piece may be a less desirable technique in Canada, as it physically separates the patient from the monitoring capabilities of the ventilator, and it is cumbersome for RTs to assemble. Fourth, despite physiological studies22–25 demonstrating the impact of humidification on breathing during assisted ventilation, the type of humidification used was not considered in determining SBT candidacy or the level of PS used during SBTs.

Three additional observations regarding to roles of health care providers, GCS measurement, and NIV utilization merit commentary. In Canada, while RTs and physicians share responsibility for daily screening and decisions regarding SBT performance, adjusting ventilator settings, and tracheal extubation; RTs actually perform these tasks. Regarding GCS computation in intubated patients, our survey results suggest a level of uncertainty concerning how best to assess the verbal scale score. It is essential to underscore the importance of standardizing GCS assessment and computation in order to enhance communication and to ensure the reliability and accuracy of illness severity scores that use the GCS as a component part. Finally, we noted considerable ambiguity regarding the role of NIV during weaning and in the post-extubation period. Ambiguity surrounding the role for NIV was lowest for post-extubation respiratory failure, despite evidence from RCTs26,27 demonstrating a lack of benefit for this indication. Conversely, although evidence supports a role for prophylactic application of NIV following tracheal extubation in high-risk patients, at least one-third of our respondents never apply NIV for this indication.28–31

Our survey represents a systematic attempt to characterize mechanical ventilation discontinuation practices in Canada. With the goals of obtaining information regarding clinical practice and organizational aspects of weaning and tracheal extubation in our ICUs, we used a multimodal approach to identify RTs and Critical Care Site physicians in leadership roles at teaching hospitals across Canada. To limit instrument bias and to enhance questionnaire clarity, comprehensiveness, and reliability, we used a rigorous approach to questionnaire development, testing, and administration. We formatted, tested, and administered our questionnaire in both national languages using rigorous methodology.15 We used strategies in postal questionnaire development (university origin, cover letter endorsement, colour printing), testing (pilot testing), and administration (provision of an incentive, first-class mail delivery, reminders to non-respondents) demonstrated to enhance response rate.32 Finally, we obtained a high response rate to our questionnaire which enhances the external validity of our findings. Our survey also has limitations. As we administered the survey to head RTs and Critical Care Site Chiefs at teaching hospitals, our findings may not be generalizable to community hospitals and other clinicians involved in weaning. Our survey reflects the stated rather than the actual practices of our respondents. While information regarding practices can be obtained using both study designs, information regarding practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs33 can only be ascertained using survey methodology.

In conclusion, our cross-sectional, self-administered, descriptive, postal survey summarizes the stated practices and organizational aspects of weaning in Canadian teaching hospital ICUs. We found that SBTs and PS are common features of weaning in our teaching hospitals. We did not identify important regional variation in whether clinicians ever perform SBTs, the modes used prior to a SBT, and the use of PS and SBTs during weaning. Compared with the published literature, our survey suggests that weaning practices have evolved over time and that weaning practice variation may be greater on an international level compared to a national level.

References

Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Carding for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population. JAMA 2000; 284: 2762–70.

Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: the contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 1266–71.

Esteban A, Alia I, Ibanez J, Benito S, Tobin MJ. Modes of mechanical ventilation and weaning. A national survey of Spanish hospitals. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Chest 1994; 106: 1188–93.

Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, et al. Effect of the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1864–9.

Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 1997; 25: 567–74.

Marelich GP, Murin S, Battistella F, Inciardi J, Vierra T, Roby M. Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses: effect on weaning time and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 2000; 118: 459–67.

Esteban A, Alia I, Gordo F, et al. Extubation outcome after spontaneous breathing trials with t-tube or pressure support ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156: 459–65.

Esteban A, Alia I, Tobin MJ, et al. Effect of spontaneous breathing trial duration on outcome of attempts to discontinue mechanical ventilation. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159: 512–8.

Perren A, Domenighetti G, Mauri S, Genini F, Vizzardi N. Protocol-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation: clinical outcome in patients randomized for a 30-min and 120-min trial with pressure support ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2002; 28: 1058–63.

Brochard L, Rauss A, Benito S, et al. Comparison of three methods of gradual withdrawal from ventilatory support during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 150: 896–903.

Esteban A, Frutos F, Tobin MJ, et al. A comparison of four methods of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 345–50.

Esen F, Denkel T, Telci L, et al. Comparison of pressure support ventilation (PSV) and intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) during weaning in patients with acute respiratory failure. Adv Exp Med Biol 1992; 317: 371–6.

Ely EW, Bennett PA, Bowton DL, Murphy SM, Florance AM, Haponik EF. Large scale implementation of a respiratory therapist-driven protocol for ventilator weaning. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159: 439–46.

Vitacca M, Clini E, Porta R, Ambrosino N. Preliminary results on nursing workload in a dedicated weaning center. Intensive Care Med 2000; 26: 796–9.

Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008; 179: 245–52.

Riker RR, Picard JT, Fraser GL. Prospective evaluation of the Sedation-Agitation Scale for adult critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 1325–9.

Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J 1974; 2: 656–9.

Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 1338–44.

Venus B, Smith RA, Mathru M. National survey of methods and criteria used for weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 1987; 15: 530–3.

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 2002; 287: 345–55.

Leung P, Jubran A, Tobin MJ. Comparison of assisted ventilator modes on triggering, patient effort, and dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: 1940–8.

Le Bourdelles G, Mier L, Fiquet B, et al. Comparison of the effects of heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers on ventilation and gas exchange during weaning trials from mechanical ventilation. Chest 1996; 110: 1294–8.

Pelosi P, Solca M, Ravagnan I, Tubiolo D, Ferrario L, Gattinoni L. Effects of heat and moisture exchangers on minute ventilation, ventilatory drive, and work of breathing during pressure-support ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 1996; 24: 1184–8.

Iotti GA, Olivei MC, Palo A, et al. Unfavorable mechanical effects of heat and moisture exchangers in ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 1997; 23: 339–405.

Campbell RS, Davis K Jr, Johanniqman JA, Branson RD. The effects of passive humidifier dead space on respiratory variables in paralyzed and spontaneously breathing patients. Respir Care 2000; 45: 306–12.

Keenan SP, Powers C, McCormack DG, Block G. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for postextubation respiratory distress: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 287: 3238–44.

Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, et al. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for respiratory failure after extubation. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2452–60.

Squadrone V, Coha M, Cerutti E, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for treatment of postoperative hypoxemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 589–95.

Kingden-Milles D, Muller E, Buhl R, et al. Nasal-continuous positive airway pressure reduces pulmonary morbidity and length of hospital stay following thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Chest 2005; 128: 821–8.

Ferrer M, Valencia M, Nicolas JM, Bernadich O, Badia JR, Torres A. Early noninvasive ventilation averts extubation failure in patients at risk: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 164–70.

Nava S, Gregoretti C, Fanfulla F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation to prevent respiratory failure after extubation in high-risk patients. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 2465–70.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002; 324: 1183.

Rubenfeld G. Surveys: an introduction. Respir Care 2004; 49: 1181–5.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the members of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Critical Care Interest Group (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario) for their assistance in developing and testing the questionnaire.

Sources of financial support

Dr. Burns holds a Clinician Scientist award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Financial disclosure

No author has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is accompanied by an editorial. Please see Can J Anesth 2009; 56: 8.

This study is conducted for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, K.E.A., Lellouche, F., Loisel, F. et al. Weaning critically ill adults from invasive mechanical ventilation: a national survey. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 56, 567–576 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9124-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9124-8