Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topical application of antifibrinolytic drugs to reduce postoperative bleeding and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery.

Methods

We searched The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCI-EXPANDED for all randomized controlled trials on the topic. Trial inclusion, quality assessment, and data extraction were performed independently by two authors. Standard meta-analytic techniques were applied.

Results

Eight trials (n = 622 patients) met our inclusion criteria. The medication/placebo was applied into the pericardial cavity and/or mediastinum at the end of cardiac surgery. Seven trials compared antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin or tranexamic acid) versus placebo. They showed that, on average, topical use of antifibrinolytic agents reduced the amount of 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss by 220 ml (95% confidence interval: −318 to −126, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 93%) and resulted in a saving of 1 unit of allogeneic red blood cells per patient (95% confidence interval: −1.54 to −0.53, P < 0.0001, I 2 = 55%). The incidence of blood transfusion was not significantly changed following topical application of the medications. One study comparing topical versus intravenous administration of aprotinin found comparable results between the two methods of administration for the above-mentioned outcomes. No adverse effects were reported following topical use of the medications.

Conclusion

This review suggests that topical application of antifibrinolytics can reduce postoperative bleeding and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery. These promising findings need to be confirmed by more trials with large sample size using patient-related outcomes and more assessments regarding the systemic absorption of the medications.

Résumé

Objectif

Le but de cette étude méthodique était d’évaluer l’efficacité et l’innocuité de l’application topique d’agents anti-fibrinolytiques afin de réduire les saignements et les besoins transfusionnels postopératoires chez les patients subissant une chirurgie cardiaque avec circulation extra-corporelle.

Méthode

Nous avons fouillé les bases de données suivantes afin d’extraire toutes les études randomisées contrôlées traitant de cette question : The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE et SCI-EXPANDED. L’inclusion des études, l’évaluation de la qualité et l’extraction des données ont été réalisées de façon indépendante par deux auteurs. Des techniques de méta-analyse standard ont été utilisées.

Résultats

Huit études (n = 622 patients) ont satisfait à nos critères d’inclusion. Le médicament/placebo a été appliqué dans la cavité péricardique et/ou dans le médiastin à la fin de la chirurgie cardiaque. Sept études ont comparé des agents anti-fibrinolytiques (aprotinine ou acide tranexamique) à un placebo. Ces études ont montré que, en moyenne, l’application topique d’agents anti-fibrinolytiques a réduit les pertes sanguines des drains thoraciques durant les premières 24 h postopératoires de 220 ml (intervalle de confiance 95% : –318 à –126, P < 0,00001, I2 = 93 %) et a permis de sauver un culot globulaire allogénique par patient (intervalle de confiance 95% : –1,54 à –0,53, P < 0,0001, I2 = 55 %). L’incidence de transfusion n’a pas subi de modification significative à la suite de l’application topique des médicaments. Une étude comparant l’application topique à l’administration intraveineuse d’aprotinine a donné des résultats comparables entre les deux méthodes d’administration pour les devenirs mentionnés ci-dessus. Aucun effet secondaire n’a été rapporté en relation avec l’application topique des médicaments.

Conclusion

Notre étude suggère que l’application topique d’agents anti-fibrinolytiques peut réduire les saignements et les besoins transfusionnels postopératoires chez les patients subissant une chirurgie cardiaque avec circulation extra-corporelle. Ces résultats prometteurs devraient cependant être confirmés par d’autres études présentant une taille d’échantillon plus importante examinant les devenirs associés aux patients et comprenant d’autres évaluations concernant l’absorption systémique des médicaments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On-pump cardiac surgery can be associated with excessive bleeding due to several factors such as increased fibrinolysis induced by extracorporeal circulation and surgical trauma.1 As a result, 23.8–51.9% of patients require blood transfusion, and re-exploration is performed in 2–6% of the cases to control bleeding.2

In spite of the recent advances in surgical techniques and the perioperative care, the amount of bleeding remains as high as 600–1200 ml. Hence, in most centres, a median of 2 to 3 units of red blood cells (RBCs) per patient is required.3 Patients undergoing cardiac surgery are vulnerable to the consequences of blood loss which can lead to increased mortality, morbidity, and poor quality of life.4 Issues such as the cost of blood, limited availability, and the potentially harmful effects of transfusion necessitate developing more effective methods to minimize surgical blood loss. Antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin, tranexamic acid, and ε-aminocaproic acid) have been shown to inhibit fibrinolysis and, thus, reduce bleeding in cardiac surgery.5 However, recent studies on large numbers of patients have raised growing concerns about the serious adverse effects observed following systemic administration of antifibrinolytic agents. These complications include increased mortality,6 renal toxicity,5,7,8 anaphylactic reactions,9 graft vessel occlusion,10 the risk of myocardial infarction (in high-risk cardiac surgery) following aprotinin use,11 and, because of its mechanism of action, the potential risk of thromboembolic events after tranexamic acid administration.12 Due to the natural barrier properties of the pericardium, which prevents free diffusion of substances, recent experimental studies have shown that local application of different medications into the pericardial cavity can lead to desirable therapeutic efficacy without significant systemic absorption.13–15 In light of these findings, topical application of antifibrinolytics may be an effective and safe pharmacological strategy to minimize blood loss in cardiac surgery.16–21 This systematic review aims to evaluate the best available evidence about the safety and efficacy of the topical use of antifibrinolytic drugs to reduce postoperative blood loss and transfusion requirements in adult patients having on-pump cardiac surgery.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 2008), MEDLINE from January 1966 to July 2008, EMBASE from January 1980 to July 2008, and Science Citation Index Expanded from 1945 to July 2008. We used the following keywords: aprotinin, trasylol, tranexamic, transamin, cyklokapron, epsilon-aminocaproic acid, cardiac surgery, open heart surgery, coronary artery by pass, topical, local, and intrapericardial. We exploded the following index-word terms: ‘Antifibrinolytic agents’, ‘Aprotinin’, ‘Tranexamic acid’, ‘Aminocaproic acids’, ‘Administration, Topical’, ‘Anesthesia’, ‘Cardiac surgical procedures’, ‘Cardiopulmonary bypass/adverse effects’. We also searched the on-line archives of the recent international annual meetings on the topic, i.e., American Society of Anesthesiologists, Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society, and European Society of Anesthesiologist (all since 2000), American Association for Thoracic Surgery, European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (since 2006). We hand-searched reference lists from the already retrieved articles to identify further trials. In addition, we made contact with the principal authors as well as experts in the field to identify additional published or unpublished data relevant to the review.

Study selection criteria

Two reviewers (AA and JW) independently assessed titles, abstracts, and/or the full text paper of the hits retrieved from the electronic database and the hand searches for possible inclusion according to the pre-defined selection criteria. Disagreements between the authors were resolved by the third author (FC). Studies were eligible for inclusion, regardless of the publication language, if they were randomized parallel group trials and if they evaluated topical administration of antifibrinolytic agents in adult patients undergoing elective on-pump cardiac surgery.

Assessment of the methodological quality of studies

The studies were assessed for their methodological quality by two independent raters (AA and JW) using the criteria proposed by Schulz et al.22 These criteria specify four items of assessment: double-blinding, allocation concealment, follow-up completeness, and methods used to achieve randomization. Disagreements were resolved by the third author (FC). Between assessor agreement was not measured, due to the limited numbers of included trials.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of the review included the 24-h postoperative chest tube output and the incidence and the amount of allogeneic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion. The 24-h chest tube output was considered as a surrogate measure of blood loss, because the output is mainly due to bleeding during this period. Since the amount of allogeneic RBC transfusion was reported in units in a majority of the included trials, we analyzed and reported this outcome in units. If the amount of transfusion was reported in ml, it was converted to units according to the information provided by the authors following correspondence with the authors of the included studies. We also considered listing the complications reported among the studies. The secondary outcomes were the rate of re-operation due to bleeding and the incidence of complications. In the first comparison, we analyzed the data for any antifibrinolytic agents versus placebo, regardless of the type of medication. Then we assessed the efficacy and safety of each individual antifibrinolytic agent versus placebo (e.g. aprotinin vs. placebo) or one antifibrinolytic agent compared to another (e.g. aprotinin vs. tranexamic acid). In addition, the results of the direct comparison between topical versus systemic application of antifibrinolytics, which was carried out in one trial,18 were presented in this review. All analyses were performed using Review Manager 4.2.9 software (Review Manager, version 4.2, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Pooled treatment effects were estimated using random-effect models, since statistical heterogeneity exists in all the analyses. Relative risks (RR) and weighted mean differences (WMD) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. The presence of heterogeneity of treatment effect was assessed using the Q statistic, which has an approximate chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of studies minus one. A P-value less than or equal to 0.10 indicated statistically significant heterogeneity. To quantify statistical heterogeneity, we used the I² statistic given by the formula [(Q − df)/Q] × 100%, where Q is the chi-squared statistic and df is its degrees of freedom. A value greater than 50% would be considered substantial heterogeneity.23 We also planned subgroup analyses, where possible, to determine whether effect sizes vary according to factors such as type of surgery, use of transfusion protocols, dose regimen, and the quality of study methods. Funnel plots were planned to be inspected for evidence of publication bias. Asymmetry of the funnel plot was assessed according to the Egger regression test24 and the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation tests.25

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

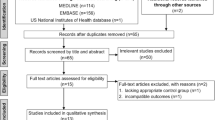

We screened 71 reports yielded by our search strategy; 26 were considered for inclusion, but 18 were subsequently excluded for reasons that are given in detail in Fig. 1.19,26–28 We eventually included 8 trials involving a total number of 622 patients. Trials came from 7 countries (Croatia, Czech Republic, Egypt, England, Germany, Italy, and Turkey) and were published between 1992 and 2007. Seven trials were published in English and one was published in the Turkish language. The characteristics of these trials are provided in Table 1. All trials included only primary operations. Patients with a known history of coagulation problems were not considered for the study. All the trials used similar methods for topical application of antifibrinolytic agents. The medication or placebo (equal amount of saline) was poured into the pericardial cavity and/or over mediastinal tissues at the end of surgery and before closure of the median sternotomy. The solutions were then suctioned out through the chest tubes, which were routinely put in place after cardiac surgery. In one study, swabs soaked in aprotinin (or placebo) solutions were packed loosely around the heart and over the mediastinal tissue.20 Average group size was 78 patients (range, 30–160). No trial was found on the topical application of ε-aminocaproic acid.

Methodological quality of the studies

The details of the methodological quality of each study are shown in Table 2. All Schulz’s criteria of methodological quality were adequately met in the four trials. Three studies, however, did not clearly report the method of randomization and allocation concealment. With regard to blinding, two trials were not clear. We contacted the authors for more information, but received no response.20,21,29 One trial was not considered double-blinded because it did not use placebo for the control group (i.e. control group = no intervention).21 All the included trials were considered for final analyses regardless of the methodological quality, as sensitivity analysis showed that, due to the quality of the study, the overall treatment effects did not significantly change. The WMD for postoperative chest tube loss was −222 ml [95% CI: −318 to −126] for all trials and −276 [95% CI: −394 to −158] after excluding studies which did not adequately meet all quality criteria. The WMD for RBC units transfused was −1.04 [95% CI: −1.54 to −0.53] for all trials and −0.97 [95% CI: −1.88 to −0.05] after excluding trials with unclear quality.

Meta-analysis

Topical application of all antifibrinolytic agents vs. placebo (seven trials, 525 patients)

Pooling of the data showed that, compared to the control, the topical application of any antifibrinolytic agent, regardless of the type, reduced the 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss by 222 ml (Fig. 2) and the amount of allogeneic RBC transfusion by 1 unit (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of publication bias, suggested by asymmetry of the funnel plots in terms of the total reduction of blood loss (P-Egger test = 0.6, P-Begg test = 0.9) or the amount of blood transfusion (P-Egger test = 0.5, P-Begg test = 0.8). The incidence of RBC transfusion was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.12), even though there was a trend in favor of the medications (Fig. 4). No adverse effects were reported in any of the included trials following topical application of antifibrinolytic agents.

Meta-analysis of the studies on topical application of antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin or tranexamic acid) vs. placebo. Outcomes: the 24-h postoperative chest tube loss. SD standard deviation, WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval, N no. of patients. Studies with insufficient data were not included

Meta-analysis of the studies on topical application of antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin or tranexamic acid) vs. placebo. Outcomes: the amount of allogeneic RBC transfusion in units. SD standard deviation, WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval, N no. of patients. Studies with insufficient data were not included

Meta-analysis of the studies on topical application of antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin or tranexamic acid) vs. placebo. Outcomes: the incidence of allogeneic RBC transfusion. TA tranexamic acid, SD standard deviation, WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval, N no. of patients. Studies with insufficient data were not included

Topical aprotinin vs. placebo (five trials, 324 patients)

Pooling of the data showed that, compared to the control, a topical application of aprotinin reduced the 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss by 200 ml, on average (Fig. 2), and the amount of allogeneic RBC transfusion by 0.8 units (Fig. 3). The incidence of RBC transfusion was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.11, Fig. 4). Heterogeneity was found among the studies in terms of the amount of treatment effects on postoperative blood loss (I 2 = 60%). To explore heterogeneity, we excluded one study29 with a very small sample size (10 patients per group), because it was statistically underpowered to detect any potential beneficial effect of the medication over placebo. No heterogeneity was found among the other four trials (WMD = −248 ml, 95% CI: −266 to −230, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0%). Re-exploration to control bleeding was reported in two trials where, in all cases, an evident surgical source of bleeding was discovered. The data of these cases were not included in the review. In one study, aprotinin levels were determined 1 h following topical application, although it was not detected in any of the patient’s blood.21

Topical tranexamic acid vs. placebo (four trials, 269 patients)

Pooling of the data showed that, compared to the control, topical application of tranexamic acid reduced the 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss by 250 ml, on average (Fig. 2), and the amount of allogeneic RBC transfusion by 1.6 units (Fig. 3). The incidence of RBC transfusion was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.88, Fig. 4). Heterogeneity was found among the studies in terms of the amount of treatment effects on postoperative blood loss (I 2 = 95%). To explore heterogeneity, we excluded one study29 with a very small sample size (10 patients per group). This resulted in no significant change in heterogeneity (I 2 = 93%). In the next step, we pooled the data of the remaining studies with the same dose of medication, i.e., two trials using 1 g of tranexamic acid. As a result, heterogeneity was reduced between these trials; however, it was not resolved (WMD = −228 ml, 95% CI: −376 to −79 ml, P = 0.003, I 2 = 68%). Re-exploration to control bleeding was reported in two trials.16,30 Unfortunately, in one of the trials, an evident surgical source of bleeding was discovered for all cases, so the data of this study were not included in the analysis.29 The other trial, however, showed that re-exploration is significantly higher in the placebo group versus the treatment group (16% vs. 2%, P = 0.014).16 In one study, the plasma concentration of tranexamic acid was assayed by gas chromatography 2 h following topical application. None of the patients had detectable levels of tranexamic acid.17

Topical aprotinin vs. topical tranexamic acid (two trials, 122 patients)

Statistical pooling of the data showed no significant difference between the two medications in terms of the 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss (WMD = −77 ml, 95% CI: −71 to 227 ml, P = 0.31) or the amount of RBC transfusion (WMD = 0.4 units, 95% CI: −1.6 to 2.39, P = 0.69). The rate of RBC transfusion, reported in only one study, was the same between the two medications.

Topical vs. systemic application of antifibrinolytics (one trial, 97 patients)

The 24-h postoperative chest tube (blood) loss was 547 ± 259 ml following topical application of aprotinin and 491 ± 217 ml after intravenous aprotinin (P = not significant). The incidence and the amount of RBC transfusion were not significantly different between the two groups.

Discussion

This systematic review includes eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the topical application of the anti-fibrinolytic drugs, aprotinin and tranexamic acid, for on-pump cardiac surgery. No trial was found regarding the topical application of another anti-fibrinolytic agent, ε-aminocaproic acid. Although aprotinin and tranexamic acid differ somewhat in their mechanisms of action, the results of this review suggest that their topical administration during cardiac surgery can reduce postoperative blood loss and the volume of allogeneic RBC transfusion to a degree that is both statistically and clinically significant. No adverse effects were reported in any of the trials. In addition, both head-to-head comparison and the results of an indirect comparison between aprotinin and tranexamic acid showed that both medications had comparable efficacy following topical application.

There are two bodies of literature that support the rationale of topical application of antifibrinolytic agents during open-heart surgery. It has been hypothesized that this method of drug delivery is both “target-directed” and “potentially safe” to reduce postoperative bleeding. These two reasons were confirmed, to some extent, by the results of our systematic review. The first suggested rationale is that topical application of antifibrinolytic agents can directly target the source of bleeding, which is the local increase in fibrinolytic activity. In patients undergoing CABG, Khalil et al. found that the local fibrinolytic activity in the pericardial cavity significantly exceeded that in the systemic circulation.31 This has also been shown by Tabuchi et al. who found that levels of thrombin-antithrombin III complex, fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation product (FDP) were significantly higher in blood from patients’ pericardial cavities than in blood from their systemic circulation.32 These findings reflect the fact that human pericardium contains very high levels of tissue activators of plasminogen, which impair stable fibrin production.33 In physiological and normal conditions, this feature prevents adhesion formation and maintains fluidity of the pericardial cavity. However, during cardiac surgery, high amounts of pericardial plasminogen activators are released following skin incision, sternotomy, and surgical tissue manipulation, which can subsequently lead to increased local fibrinolytic activity and excessive bleeding.34

Consistent with this physiological evidence, the results of our systematic review showed that the topical application of antifibrinolytics into the pericardial tissues reduced postoperative chest-tube blood loss by 200 or 250 ml, on average, in aprotinin or tranexamic acid trials, respectively. Topical application of antifibrinolytics in other types of surgeries, such as neurosurgery, where the meninges and cerebral tissues contain high levels of tissue plasminogen activators, has also been shown to reduce surgical bleeding.35,36 Therefore, based on this evidence, we can theorize that topical application of antifibrinolytics can possibly reduce surgical blood loss by the inhibition of local fibrinolysis. However, this theory should be confirmed by the direct measurement of local fibrinolytic activity (e.g. FDP in blood from the pericardial cavity) following topical application of these medications. This procedure was not performed in any of the included trials.

The amount of reduction in postoperative surgical bleeding presented in this systematic review is comparable with the values reported by two recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews concerning systemic (i.e. intravenous) administration of antifibrinolytics for on-pump cardiac surgery. In this regard, a meta-analysis by Brown et al. showed that the overall reduction of perioperative blood loss was 225–350 ml following systemic administration of antifibrinolytics.8 Also, an updated Cochrane systematic review by Henry et al. reported this amount as 380 ml for aprotinin and 260 ml for tranexamic acid.5 In addition, a head-to-head comparison by Isgro showed that topical aprotinin is equally effective as systemic aprotinin for the reduction of perioperative blood loss.18

The second reason supporting the topical use of antifibrinolytics is based on the observation that the pericardium acts as a natural barrier that minimizes the rate of systemic absorption and side effects of pharmacological agents applied locally into the pericardial cavity. In this regard, experimental studies by Waxman et al.15 and Kolletis et al.14 showed that the intrapericardial delivery of different types of medications in animals (e.g. digitalis, antiarrhythmic agents, nitric oxide) could lead to desirable therapeutic effects with little or no systemic absorption (or toxicity). Also, an animal study by Baek et al.13 showed that the clearance rate of agents from the pericardium depended on their molecular weight (MW). Their study showed that only a small fraction (<10%) of a high MW agent (70 kDa) was absorbed into the systemic circulation during the first 10 h after intrapericardial injection.

According to this information, and given the short half-life of both aprotinin (7 h) and tranexamic acid (3 h) and especially the high MW of aprotinin (6 kDa), we can postulate that the topical application of these medications will not lead to systemic absorption and toxicity. Due to the delay in absorption provided by the pericardial barrier, by the time aprotinin and tranexamic acid reach the systemic circulation, most of the drug would be biologically inactive. To some extent, this hypothesis was confirmed by the results of our review. We have found two studies measuring plasma levels of antifibrinolytics after topical application that showed no detectable systemic absorption.17,21 In addition, no adverse effects have been reported in any of the included trials.

In terms of the amount of reduction in postoperative blood loss for both the aprotinin and the tranexamic acid studies, heterogeneity exists between the results of the trials. As the variation was in terms of the size and not the direction of effect, we have little doubt about the existence of a treatment benefit with the topical application of antifibrinolytics, despite this heterogeneity. We theorize two possible reasons to explain this variability. First, the study with a small sample size of 10 patients29 was statistically underpowered to detect beneficial effects of medications over placebo. After excluding this study from meta-analysis, heterogeneity was resolved among the studies on aprotinin, but not in the studies on tranexamic acid. Second, different dose regimens were used by the trials. This factor could partially explain the variability in the studies on tranexamic acid. According to these results, it is tempting to conclude that there is a dose–response relationship for topical application of tranexamic acid. However, it should be noted that a high dose of tranexamic acid was studied in one trial, i.e., Abul-Azm’s study,16 and there might be other factors involved in the study that can affect the treatment effect. For example, in this study, a high average postoperative blood loss was observed in both study groups, which might explain why the study results showed a higher amount of reduction in postoperative bleeding.

In spite of a comprehensive search strategy, we could only find a limited number of RCTs eligible for this review. Although the number of available studies is not a restriction of conducting a systematic review, it can affect our review in several ways. First, evaluation of publication bias was not possible in this review, as both visual examination and statistical analysis of funnel plots have limited power to detect bias if the number of studies is small.23 Second, we were not able to evaluate the effect of several factors, such as type of cardiac surgery, transfusion trigger, preoperative anticoagulant use, and even dose on the overall treatment effect, due to the limited number of studies with similar characteristics that could fall into the same group for subgroup analysis. Finally, including few trials into the review, especially those with a small sample size, can pose the “small-study effect”, i.e., the tendency for small trials to have inflated treatment effect estimates because of methodological differences (either design flaws or more rigorous implementation of treatment).37 In order to address this issue, we carried out the sensitivity analysis by excluding one study with a very small sample size.28 This strategy could resolve the existing heterogeneity among the studies on aprotinin, but not the differences among studies on tranexamic acid. For future trials, we recommend studies with sample size ≥60 patients. This is based on our sample size calculation considering the main outcome as 24-h chest tube loss, the estimated efficacy as 222 ml reduction in blood loss (Fig. 2) and the standard deviation of blood loss as 300 ml (Appendix 1).

With regard to the outcome measures in the included trials, more accurate clinical tools should have been utilized to evaluate the efficacy of topical antifibrinolytics and to detect their potential complications. For efficacy outcomes, the 24-h chest tube loss was used in the included trials, which only serves as a surrogate measure of the blood loss after surgery and cannot reflect the amount of bleeding intraoperatively. Also, it seems necessary to measure the amount of red blood cell volume lost in the chest tube containers to be able to determine the exact amount of postoperative bleeding (RBC loss). Other methods, such as calculating blood loss based on the changes in postoperative hemoglobin levels, are not recommended in cardiac surgical patients as a consequence of the high fluid loads infused during surgery and the resultant hemodilution.38

For safety assessments, the amount of aprotinin or tranexamic acid in patients’ blood was only measured in a limited number of patients in two studies.17,21 Also, indirect measurement of systemic absorption of these medications and adverse effects have not been properly evaluated in the included trials. For example, screening by postoperative doppler ultrasound to detect deep vein thrombosis following tranexamic acid use has not been carried out in any of the trials. Also, monitoring of renal function, which has been shown by both observational and RCTs to be altered after aprotinin use, was not performed in the trials on topical application of the medication. Finally, the length of follow-up period was not clearly mentioned in the trials.

Many of the studies used transfusion triggers that were higher than current practice. According to a Canadian retrospective study on more than 11,800 patients undergoing cardiac surgeries, the mean hemoglobin concentration for blood transfusion was 72.5 ± 10.7 g/l.3 The transfusion trigger among the included trials, however, ranged from 70 to 100 g/l of hemoglobin concentration. This concentration can exaggerate the beneficial findings of the studies in terms of the incidence or the amount of blood transfusion. Therefore, future trials with more consistent transfusion triggers are suggested.

During the final stage of preparation of this review, we learned that Bayer Pharmaceuticals Corp., the manufacturer of aprotinin (Trasylol®), has agreed to a marketing suspension of the medication following a request by the FDA in early November 2007. This request was made based on the serious results suggested by the BART study (Blood conservation using antifibrinolytics: A randomized trial in a cardiac surgery population). This study made a comparison of systemic use of aprotinin and other lysine analogues in patients undergoing high-risk cardiac surgery, and the results showed an increase in the 30-day all-cause mortality rate in the aprotinin group (relative risk, 1.55; 95% CI: 0.99–2.42).11 For this reason, we cannot recommend the use of this medication in any kind of clinical trial, not even for topical application, which seems to be potentially safe due to less systemic absorption. However, the topical application of this medication is still an alternative option, which can be studied in future experimental studies (animal model) specifically designed to evaluate its systemic absorption and pharmacodynamics.

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that topical application of aprotinin or tranexamic acid for on-pump cardiac surgery can significantly reduce postoperative bleeding and transfusion requirements. The included trials did not show any systemic absorption following topical application of antifibrinolytics; however, these results need to be confirmed by additional assessments with sensitive tools measuring systemic absorption of topically applied medications. Future high quality RCTs on the topical application of tranexamic acid, with a larger sample size (at least 60 patients), are recommended to address this issue, to focus on patient-related outcomes (e.g. quality of life, postoperative morbidity and mortality), and to carry out dose–response analysis. Further clinical trials on topical aprotinin are not recommended until there are additional results of experimental research (animal model) regarding systemic absorption of the medication.

References

Paparella D, Brister SJ, Buchanan MR. Coagulation disorders of cardiopulmonary bypass: a review. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 1873–81.

Hartmann M, Sucker C, Boehm O, Koch A, Loer S, Zacharowski K. Effects of cardiac surgery on hemostasis. Transfus Med Rev 2006; 20: 230–41.

Hutton B, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A, McIntyre L, Kmetic A, Hebert PC. Transfusion rates vary significantly amongst Canadian medical centres. Can J Anesth 2005; 52: 581–90.

Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Yau TM, et al. The independent association of massive blood loss with mortality in cardiac surgery. Transfusion 2004; 44: 1453–62.

Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, et al. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (4): CD001886.

Mangano DT, Miao Y, Vuylsteke A, et al. Mortality associated with aprotinin during 5 years following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA 2007; 297: 471–9.

Karkouti K, Beattie WS, Dattilo KM, et al. A propensity score case-control comparison of aprotinin and tranexamic acid in high-transfusion-risk cardiac surgery. Transfusion 2006; 46: 327–38.

Brown JR, Birkmeyer NJ, O’Connor GT. Meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness and adverse outcomes of antifibrinolytic agents in cardiac surgery. Circulation 2007; 115: 2801–13.

Beierlein W, Scheule AM, Dietrich W, Ziemer G. Forty years of clinical aprotinin use: a review of 124 hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; 79: 741–8.

Westaby S, Katsumata T. Aprotinin and vein graft occlusion—the controversy continues. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 116: 731–3.

Fergusson DA, Hebert PC, Mazer CD, et al. A comparison of aprotinin and lysine analogues in high-risk cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2319–31.

Cid J, Lozano M. Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic red cell transfusions in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion 2005; 45: 1302–7.

Baek SH, Hrabie JA, Keefer LK, et al. Augmentation of Intrapericardial nitric oxide level by a prolonged-release nitric oxide donor reduces luminal narrowing after porcine coronary angioplasty. Circulation 2002; 105: 2779–84.

Kolettis TM, Kazakos N, Katsouras CS, et al. Intrapericardial drug delivery: pharmacologic properties and long-term safety in swine. Int J Cardiol 2005; 99: 415–21.

Waxman S, Pulerwitz TC, Rowe KA, Quist WC, Verrier RL. Preclinical safety testing of percutaneous transatrial access to the normal pericardial space for local cardiac drug delivery and diagnostic sampling. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2000; 49: 472–7.

Abul-Azm A, Abdullah KM. Effect of topical tranexamic acid in open heart surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006; 23: 380–4.

De Bonis M, Cavaliere F, Alessandrini F, et al. Topical use of tranexamic acid in coronary artery bypass operations: a double-blind, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 119: 575–80.

Isgro F, Stanisch O, Kiessling AH, Gurler S, Hellstern P, Saggau W. Topical application of aprotinin in cardiac surgery. Perfusion 2002; 17: 347–51.

Khalil PN, Siebeck M, Ismail M, et al. The critical role of aprotinin in controlling haemostasis in conjunction with non-pharmacological blood-saving strategies during routine coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Med Res 2006; 11: 386–93.

O’Regan DJ, Giannopoulos N, Mediratta N, et al. Topical aprotinin in cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 58: 778–81.

Tatar H, Cicek S, Demirkilic U, et al. Topical use of aprotinin in open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1993; 55: 659–61.

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Altman DG, Grimes DA, Dore CJ. The methodologic quality of randomization as assessed from reports of trials in specialist and general medical journals. Online J Curr Clin Trials 1995; Doc No 197: (81 paragraphs).

Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5 (updated May 2005). 4.2.5 ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2005.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–34.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50: 1088–101.

Mand’ak J, Lonsky V, Dominik J. Topical use of aprotinin in coronary artery bypass surgery. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 1999; 42(4): 139-44.

Stanisch O, Isgro F. Topical application of aprotinin in cardiac surgery (German). Z Herz- Thorax- Gefäßchir 2002; 16: 25–30.

Bizzarri F, Carone E, Capannini G, et al. Bleeding reduction in cardiac surgery: a combined approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998; 115: 1227.

Yasim A, Asik R, Atahan E. Effects of topical applications of aprotinin and tranexamic acid on blood loss after open heart surgery (Turkish). Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2005; 5: 36–40.

Baric D, Biocina B, Unic D, et al. Topical use of antifibrinolytic agents reduces postoperative bleeding: a double-blind, prospective, randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 31: 366–71.

Khalil PN, Ismail M, Kalmar P, von KG, Marx G. Activation of fibrinolysis in the pericardial cavity after cardiopulmonary bypass. Thromb Haemost 2004; 92(3): 568–74.

Tabuchi N, de Haan J, Boonstra PW, van Oeveren W. Activation of fibrinolysis in the pericardial cavity during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993; 106: 828–33.

Nkere UU, Whawell SA, Thompson EM, Thompson JN, Taylor KM. Changes in pericardial morphology and fibrinolytic activity during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993; 106: 339–45.

Jares M, Vanek T, Bednar F, Maly M, Snircova J, Straka Z. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery surgery. Int Heart J 2007; 48: 57–67.

Tzonos T, Giromini D. Aprotinin for intraoperative haemostasis. Neurosurg Rev 1981; 4: 193–4.

Labadie EL, Glover D. Local alterations of hemostatic-fibrinolytic mechanisms in reforming subdural hematomas. Neurology 1975; 25: 669–75.

Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 982–9.

Slight RD, Bappu NJ, Nzewi OC, McClelland DB, Mankad PS. Perioperative red cell, plasma, and blood volume change in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Transfusion 2006; 46: 392–7.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank Dr. Baric and colleagues who generously responded to our request regarding further information on their study.

Funding sources

Funding from Department of Anesthesia, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network. No external funding.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

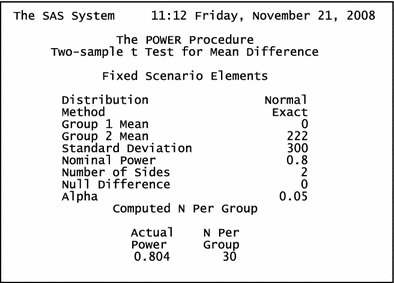

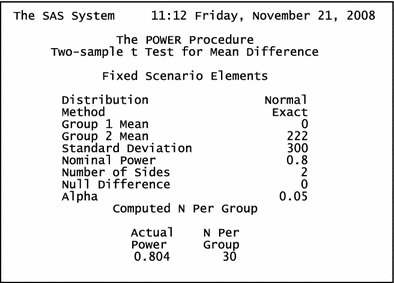

Appendix 1: suggested sample size for future studies

Appendix 1: suggested sample size for future studies

We made the following assumptions in order to calculate the suggested sample size for future studies on topical application of antifibrinolytics to reduce postoperative blood loss:

-

(1)

Primary outcome: 24-h chest tube blood loss

-

(2)

Pooled estimate of efficacy: 222 ml reduction in blood loss (Fig. 2)

-

(3)

Pooled standard deviation of blood loss: 300 ml using the SDs from the included studies using the following equation:

$$ pooledSD = \surd ( {SD_{1}^{2} + \cdots + SD_{n}^{2} } )/n) $$where SD1,…,SD n are standard deviations of the mean blood loss reported in each trial, and n is the total number of trials. Using SAS software, the required sample size is estimated as 30 per group (t-test two tailed effect size = 222 ml, SD = 300 ml, alpha = 0.05, and power = 0.8).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abrishami, A., Chung, F. & Wong, J. Topical application of antifibrinolytic drugs for on-pump cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 56, 202–212 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-008-9038-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-008-9038-x