Abstract

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), a highly toxic mycotoxin, always contaminated in a variety of agricultural products. Camelid variable domain of heavy chain antibody (VHH) is a noteworthy reagent in immunoassay, owing to its excellent characteristics. Immunization of camelid animals is a straightforward strategy to produce VHHs. In this study, to avoid the dependence on the large animals, the camelized, murine antibody (cVHs) against AFB1 was prepared in vitro based on the identities between murine VH and camelid VHH and then to develop an immunoassay for AFB1. A murine anti-AFB1 VH fragment (VH-2E6) was selected for camelization through replacement of conserved hydrophobic residues in framework region 2 (FR2) (cVH-FR2), point mutation at position 103 in the FR4 region (cVH-103), and CDR3-grafted with a high AFB1-affinity VHH (cVH-Nb26). The cVH-Nb26 had a yield of 5 mg/L as refolded protein expressed from Escherichia coli and 10 mg/L expressed from Pichia pastoris. Compared with anti-AFB1 single-chain fragment variable (scFv) 2E6, cVH-Nb26 performed more than 20-fold enhancement of AFB1-binding interactions. Although the AFB1-affinity of cVH-Nb26 cannot meet the application requirement in the present form, our study provides effective strategies for preparation of camelized antibody in vitro, which could be a promising immunoreagent for AFB1 detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), produced mainly by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, is classified as class I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC 1993). AFB1 is also stable to heating and acid conditions, making it hard to completely eliminate from contaminated agricultural products (Raters and Matissek 2008). Globally, the consumption of AFB1-contaminated food and feed stuff is considered as the major exposure to human beings (Kumar et al 2016), and their strict maximum permissible limits were set in many countries. Therefore, AFB1 detection and quantitation are essential in most countries and regions in the world (Xue et al. 2019). Antibody-based immunoassays are useful screening approaches for AFB1 detection owing to their high sensitivities and simple operations. Most enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for AFB1 detection are based on generation and production of antibodies by polyclonal and monoclonal technologies (Wu et al. 2019) and have been reported in many publications (Dixon-Holland et al. 1988; Gathumbi et al. 2001; Li et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019). Because of its low molecular weight (312.27 g/mol), AFB1 should be first derived to AFB1-oxime derivative and then conjugated with a carrier protein to make a complete immunogen. The polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies were obtained by injection to rabbits or mice. Polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies are essential for monitoring aflatoxins for decades, but their generation is expensive, each batch of antibody must be recharacterized, and suppliers are limited.

In order to reduce exposure to AFB1 and avoid the complex operation, efforts have been made to produce higher affinity antibodies in vitro through antibody-antigen-binding interactions. Single-domain antibodies (VHHs or nanobody) derived from camels are supposed to be the best choice, due to its smallest functional entity for antigen-binding (~ 15 kDa) (Hamers-Casterman et al. 1993; Fridy et al. 2014), the possibility of simple modification at genetic levels (Wang et al. 2015; Bever et al. 2016; Li et al. 2021), and the stability against temperature and organic solvents (Kim et al. 2012; He et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014). Although the immunization of a camelid animal constitutes a bottleneck for VHH production (Muyldermans, 2020), its ease-to-manipulate at genetic level makes synthesis a camelized AFB1-binding fragment in vitro possible based on the gene sequence and protein structure.

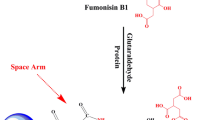

The variable region of heavy chain (VH) derived from murine antibody is supposed to be an appropriate candidate for the camelized antibody (Fig. 1), owing to its high identity with VHHs in their framework of family III (Vincke et al. 2009). Although in the absence of light chain, VH fragment represents a weak affinity with the antigen and tends to coagulate; it is still referred as a more critical fragment than the variable region of light chain (VL) in the aspect of antigen-binding interaction (Rangnoi et al. 2018). Based on VHs, the strategies of camelized VHs include the following: (1) converting hydrophobic residues at positions 37, 44, 45, and 47 on the framework 2 (FR2) of VH (numbering according to Kabat et al. 1992) to hydrophilic residues; (2) insertion of an extra loop formed by a CDR1–CDR3 disulfide linkage, which is frequently found in VHHs (Kim et al. 2014); and (3) reshaping CDRs of an antibody into another species antibody, which is also helpful to understand animal species-dependent compatibility and further explore the antigen–antibody-binding mechanism. The variable domains of murine anti-nucleic acid antibody 3D8 were reshaped to the FRs of a chicken antibody, maintaining its DNA binding, DNA hydrolysis, and cellular internalizing activities and reducing the immunogenicity in chickens (Roh et al. 2015).

Instead of dependence on large camelid animals, camelized, murine VHs (cVHs) against AFB1 were constructed in this study. The VH domain was cloned and expressed from the anti-AFB1 single-chain fragment variable antibody (scFv) 2E6, which was produced previously in our lab (Liu et al. 2015). Anti-AFB1 cVHs were prepared by gene mutagenesis in FR2 and FR4, reshaping CDR3 from a reported VHH-Nb26 (He et al. 2014). Based on the cVHs, the immunoassay for AFB1 detection was developed, and the mechanism of their AFB1-binding interactions was analyzed.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

AFB1 standards, bovine serum albumin (BSA), polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000), and 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Restriction enzyme NcoI, XhoI, KpnI, and XbaI were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). Mouse anti-His Tag Mab and goat anti-mouse IgG (HRP conjugate) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). HisPur Ni–NTA resin, B-PER extraction reagent, and Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottom 96-well plates were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL, USA). Coating antigens AFB1-OVA were formed by AFB1-oxime derivative coupling with carrier proteins in our laboratory (Ye et al. 2016).

Preparation of murine VH genes and its protein expression

A recombinant vector encoding the anti-AFB1 scFv 2E6 gene was prepared in our previous study (Liu et al. 2015) and used as a DNA template. The primers (v2E6-F 5′-CATGCCATGGGCGAGGTGAAGCTGGTGGAGTCT-3′, v2E6-R 5′-CCGCTCGAGTGAGGAGACTGTGA-3′) with Nco I and XhoI were used to amplify the VH gene from scFv 2E6 and inserted to pET22b. The vector pET22b-VH-2E6 was transferred into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3). The steps of expression and purification were performed as described previously (Wang et al. 2014) with slight modifications. In brief, a fresh clone of VH-2E6 was grown at 37 °C overnight in Super Broth (SB) medium containing 50 μg/mL of ampicillin. The cultured solution was transferred to 100 mL of SB medium at the ratio of 1:100 (v/v) to an OD600nm of 0.6–0.8, and then, expression was induced by 1.0 mM IPTG. After 8 h of shaking, pelleted cells were collected from centrifugation at 8000 × g for 15 min and then resuspended in 20 mL of PBS containing 1% Triton-X100. Under the ultrasonic conditions (300 W, 3 s on, 3 s off), targeted protein was purified by His-tag Ni–NTA column (Wang et al. 2014) and evaluated by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels (He et al. 2014). The protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm by UV spectroscopy NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Construction of camelized, murine VH chimera

Three of the VH chimera were designated as follows: (1) cVH-FR2, with point mutations V37F, G44E, L45R, and W47G in FR2 region based on VH-2E6 sequence; (2) cVH-103, a mutation of W103R in FR4 using cVH-FR2 as a template; and (3) cVH-Nb26, with the CDR3 region of cVH-103 substituted with the CDR3 fragment from a donor anti-AFB1 VHH Nb26, perform an IC50 of 0.754 ng/mL in VHH ELISA (He et al. 2014). The amino acid sequences of the VH chimera are shown in Fig. 2. The genes of cVH-FR2 and cVH-103 were constructed by overlap extension PCR with the primers and conditions listed in Supplementary files (Table S1). cVH-2E6 genes were divided into two fragments with a 12 bp of overlap, where four additional residue mutations (V37F, G44E, L45R, and W47G) were used to construct cVH-FR2. The genes of cVH-Nb26 were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd (China).

Expression and purification of VH chimera

Escherichia coli expression system

The genes of the VH chimera were encoded into pET-22b( +) at Nco I and XhoI. The proteins were expressed by IPTG induction in SB media and checked by SDS-PAGE and western blot, which was performed to confirm the soluble expression of the recombinant protein. This was accomplished by with a mouse anti-His Tag antibody and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG.

In order to enhance the expression, the bacteria containing the cVH-FR2 and cVH-Nb26 encoded vectors were grown in 100 mL of self-induce medium at 37 °C to reach an OD600nm of 0.6–0.8 and kept in self-induction media at 16 °C and 37 °C for 8 h. The cell suspensions were kept on ice and lysed by the protein extraction reagent B-PER. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 8000 × g for 20 min and washed with PBS twice. Then, the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of PBS containing 10% glycerol and sonicated (300 W, 3 s on, 3 s off) for 10 min to break the cells. After centrifugation to remove the supernatant, the pellet was resuspended with ten times of PBS containing 1% Triton-X100 and 5 mM EDTA and sonicated again. The previous steps were repeated twice to remove non-protein substances, the inclusion bodies were washed in PBS and dissolved in denaturing buffer (DB, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris–HCl, 8 mM urea, pH 8.0), then added 10 mM of DTT and stirred at room temperature for 2–3 h. The sample was dialyzed with PBS containing 0.3 mM of oxidized glutathione and 3 mM of reduced glutathione to remove the free urea. The refolding fraction was collected and checked by SDS-PAGE.

The gene of cVH-103 was subcloned into the pATX-SUMO expression vector at restriction enzyme site BamHI and XhoI. The protein was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS and induced at 16 °C for 16 h, 28 °C for 4 h, and 37 °C for 4 h, respectively. The protein of SUMO-cVH-103 was purified and then dialyzed with TBS (pH 8.0) buffer.

Pichia pastoris expression system

The gene fragments of cVH-FR2 and cVH-Nb26 were amplified with primers (yeast—F: 5′-CGGGGTACCGAGGTGAAGCTGGTGGAGTCT3′, yeast—R: 5′-CTAGTCTAGAGAGGAGACTGTGAG-3′), which were designed without stop codons between restriction sites of KpnI and XbaI. After digestion, the amplified fragments were introduced into the pPiczaA (3.5 k) vector. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells and selected on LB agar plates containing 50 µg/mL of zeocin. The genes in positive clones were extracted and linearized with SacI, which was transformed into the P. pastoris strain X-33 and selected on YPD plates containing 50 µg/mL of zeocin. For further purification, positive clones of P. pastoris transformants were cultured using buffered glycerol-complex medium (2% of peptone, 1% of yeast extract, 100 mM KH2PO4/KOH buffer pH 6.0, 1.34% of yeast nitrogen base, 0.04 mg/mL of biotin, and 1% of glycerol) and induced by buffered methanol-complex medium, which was substituted 1% of glycerol to 0.5% (v/v) of methanol. Absolute methanol was added every 24 h to maintain induction for the next 72 h. All processes were performed at 28 °C. The culture supernatant was collected and purified by Ni–NTA, followed by checked by SDS-PAGE.

Titer determination of VH chimera

The titers of VH-2E6 and cVH chimera against AFB1 were measured by ELISA according to the method of Ebersole et al. (1980) (2010). Each well of microtiter plates was coated with 100 µL, 5 µg/mL of AFB1-OVA in coating buffer (pH 9.6) at 4 °C overnight. Then, the plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated with blocking solution (3% skimmed milk in PBS) at 25 °C for 1 h. After washing steps, 100 µL of VH or cVH chimera were added to each well for incubation. Following another washing step, the plates were subsequently incubated with 100 µL of mouse anti-His Tag Mab (1:4000) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:4000). The TMB substrate (400 μL of 0.6% TMB in DMSO and 100 μL of 1% H2O2 diluted with 25 mL of 0.1 mol/L citrate-acetate buffer, pH 5.5) was used to visualize the reaction, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The titer was defined as the dilution of antibody which shows OD450nm 2 times higher than the control medium.

Development of indirect competitive ELISA

AFB1-coating antigen was diluted to 5 µg/mL and then coated on the plates overnight. After washing and blocking steps, AFB1 in a series of concentrations was diluted in PBS buffer containing 10% of methanol and added to the coated plate, then followed by the optimized concentration of VH-Nb26. The subsequent steps were the same as above. The sensitivity of icELISA defined as the half-maximum inhibition concentration (IC50) value and the limit of detection (LOD) expressed as the IC10 were obtained from a four-parameter logistic equation by SigmaPlot 10.0.

The specificity of the icELISA was tested by measuring the cross-reactivity using AFB1 analogs (AFB2, AFG1, AFG2, and AFM1). A series of concentration of AFB1 analogs from 4 µg/mL was to competitive bind with cVH-Nb26 to calculate the cross-reactivity.

Homology modeling of cVH-Nb26 and molecular docking

The model template was blasted from PDB (http://www1.rcsb.org/) and was checked through PROCHEK to calculate the favored regions, additional allowed regions, generously allowed regions, and disallowed regions to predict the protein fold quality. Further, the structure quality was verified using MolProbity and Verify 3D to determine its compatibility. The molecular docking studies were performed by AutoDock Vina software version 5.6 at default parameters (Morris et al. 2009). The best interaction complex was selected on the basis of the lowest binding energy. The docking visualization and the analysis of antibody-AFB1 interaction were carried out by Discovery Studio 2017.

Results and discussions

Construction of pET22b-VH-2E6 and its expression

Mab 2E6 and its scFv were constructed previously in our laboratory (Liu et al. 2015). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of Mab 2E6 and its scFv with VH-linker-VL against AFB1 were 85.76 ng/mL and 50 μg/mL, respectively (Liu et al. 2015). Taking the scFv 2E6 gene as a template, the recombinant vector pET22b-VH-2E6 was constructed, with a His-tag at its C-terminal and transferred into E. coli. After IPTG induction, a brighter band was observed at approximately 15 kDa, indicating VH-2E6 were successfully expressed (Fig. 3A). After cell lysis by sonication and purification by a Ni–NTA column, one single band was obtained at approximately 15 kDa, which agreed with the predicted size of VH-2E6 (Fig. 4A). Generally, VH domains worked in complex with the VL domain. They appeared aggregation without VLs (Ward et al. 1989), due to the exposure of the hydrophobic surfaces at the VH/VL interface. However, in our study, converse results were observed that VH fragment from scFv 2E6 against AFB1 was expressed in E. coli system with a relative high yield of 17 mg/L in the form of soluble protein.

SDS-PAGE analysis of VH-2E6 A and cVHs B, C expression in E. coli. (M: protein marker; BI: before induction; AI: after IPTG induction; W1–W2: collection by wash buffer with 10 mM imidazole; E1–E4: collection by elution buffer with 150 mM imidazole; lane 1: refolded cVH-FR2; lane 2: refolded cVH-2E6; lane 3: SUMO-cVH-103)

Designation of VH chimera and construction of their vectors

Three VH chimera were designed, and their pET-22-cVHs vectors were constructed in this study. cVH-FR2 has the sequence of VH 2E6 with the point mutations at positions V37F, G44E, L45R, and W47G. cVH-103 has the sequence of cVH-FR2 with a substitution at position W103R. The sequence of cVH-Nb26 corresponding to the CDR3 was substituted with a CDR3 fragment from VHH Nb26 against AFB1, which was obtained from an immunized VHH library (He et al. 2014) Two fragments of VH1 (1–141 nt) and VH2 (130–351 nt) from VH-2E6 gene were amplified to make the whole gene of cVH-FR2 by SOE PCR and then inserted into pET-22b with NcoI and XhoI digestion. The mutations at position 44, 45, and 47 in FR2 in the VH domain were considered the critical residues for the VH/VL interface positions. Residue of Phe or Tyr at position 37 was conserved in camelid VHHs. Although W103 located in the FR4 domain was a highly conserved residue for VH to interact with the VL domain, 10% of camelid VHHs have this position Arg as a substitution (Desmyter et al. 2001). A rabbit-derived VH was mutated W103R, showing the protein expression with reduced aggregation (Silva et al. 2004). The cVH-Nb26 was constructed due to the importance of the CDRs, especially CDR3, for antigen binding and its aggregation resistance (Wu et al. 2010). All the recombinant vectors were checked by digestion with their restriction enzymes and sequencing by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Expression of VH chimera in prokaryotic systems

The recombinant vectors containing VH chimera genes were transformed into the commonly used expression strain E. coli Rosetta (DE3). The culture, Super Broth, and self-induced media were respectively used for protein expression. After self-induction, a brighter band at approximately 15 kDa was observed both for expression of cVH-FR2 and cVH-Nb26 at 37 °C (Fig. 3A). No obvious expression was observed for cVH-103, although the culture, strains, and incubation temperature were optimized. Western blot analysis was used to confirm that the mutations of VH chimera largely reduced the intracellular supernatant expression in comparison with the original murine VH-2E6. Especially the protein with mutation at position W103R largely restrained its expression (Fig. 3B). While, the CDR3 loop of camelid VHH Nb26 against AFB1 provided a stable hydrophobic interaction with the FR regions and made the protein expression reappear, despite large amounts of protein misfolding which largely existed in the inclusion body (Fig. S1). Thus, the purified protein of cVH-FR2 and cVH-Nb26 from inclusion bodies were refolded and checked by UV spectrophotometer, with protein yields of 4 mg/L and 5 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 4B).

In order to promote the expression, the gene of cVH-103 was inserted to a plasmid with a SUMO tag, a small ubiquitin-like modifier protein, to express a fusion protein SUMO-VH-103. The strain of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS was used, resulting in higher expression levels of the target protein and less heteroprotein at 37 °C. After purification, fusion protein cVH-103-SUMO had yields of 0.3 mg/L (Fig. 4C).

The residues at positions 37, 44, 45, and 47 are commonly conserved in camelid VHHs. The mutation at position 37 (Val to Phe or Tyr) was regarded as necessary for maintaining the “true structural integrity” of camelized VHs. The hydrophilic residues in camelid VHHs to replace the hydrophobic residues in VH/VL interface positions (G44E, L45R, and W47G) could reduce its aggregation and block the formation of a heterodimer between VH and VL (Kim et al. 2014). In 98% of human and murine VHs, L45 is conserved with the role of VH-VL association. Due to the large hydrophobic surface covered by the VL, almost all the VHs domains from mammals tended to aggregate. The residue W103, exposed its side chain to interact with the VL, also can increase the soluble protein expression. The scFv 2E6 against AFB1 has been successfully expressed mainly in the form of inclusion body (Liu et al. 2015), while, in this study, the VH 2E6 was easy to express in cell periplasm and purify in soluble form. Human VH ab8, specific for SARS-CoV-2 was selected from a high-affinity human antibody VH library, also did not aggregate in the absence of VL (Li et al. 2020). Interestingly, mutations cVH-FR2 and cVH-103 reduced the protein expression and significantly increased their aggregation. There is a possibility of the influences on the other residues to the hydrophilicity at the molecular surface. The hydrophobic residues and negatively charged residues in non-CDR loops may mediate the aggregation behaviors of VHHs. For camelid VHHs, the residues in FRs also influenced the protein production and its stability. Mutations at 1E/D, 3Q, 5 V, and 6E within FR1 for anti-BoNT VHH were reported to offer an increase in protein production from 3 to 8 mg/L (Shriver-Lake et al. 2017). However, this reduction on protein production in this study was complemented by grafting CDR3 to the scaffold structure of cVH-103 with CDR3 of Nb26, which has been reported to be expressed as a soluble protein from E. coli TOP10F′ containing a vector of pComb3X-Nb26 (He et al. 2014). The longer CDR3 was always present in camelid VHHs, making the resulting VHHs more flexible and better at penetrating into active sites to bind tightly within cracks and pockets of protein antigens (Ding et al. 2019).

Expression of cVH-Nb26 in the Pichia pastoris expression system

Owing to the lower refolded expression from inclusion body, cVH-Nb26 were produced in a yeast expression system, which is beneficial to express heterologous proteins in a soluble, functional, and correctly folded way. The plasmid pPICZαA was linearized with SacI restriction enzyme that contained unique site in the 5′ AOX1 region, followed by digestion to form a recombinant vector pPICZaA-cVHs for insertion into the Pichia genome. The supernatants of the X33 strain containing pPICZaA-cVHs vector were checked by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. The cVH-Nb26 was successfully expressed, as a brighter band at approximately 35 kDa was observed in SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 5). The larger-than-predicted protein might be attributed to its N-glycosylation and O-glycosylation (Liu and Huang 2018). The O-linked glycosylation sites of VH-Nb26 were predicted through website at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang/. Nine possible sites of O-linked glycosylation (oligosaccharides are attached to Ser or Thr residues through a glycosidic linkage) were performed in the sequence of cVH-Nb26; among them, the sites of Thr117, Ser121, and Ser122 showed the most probability with O-linked glycosylation to be consistent with the MW increase. The cVH-Nb26 was produced and quantified by UV–Vis spectrophotometer, with approximately 10 mg/L of the protein yield, which showed twice greater than the yields from E. coli expression.

Pichia pastoris is a methylotrophic yeast, and it has been one of the most successful systems to express heterologous protein. This microorganism can use methanol as sole carbon and energy source. In the presence of methanol, the AOX1 promoter was induced, and the recombined protein was secreted to the external environment or the cell with appropriate folding (Karbalaei et al. 2020). It is also typical of Pichia pastoris to express high levels of heterologous protein and effectively mimic the glycosylation that existed in its native host. The high yield of 17 mg/L anti-AahI VHH was obtained in Pichia pastoris expression, which was almost six times greater than the yields in E. coli expression (Ezzine et al. 2012). This was also supported by cVH-Nb26 in this study.

Antigen-binding analysis of VH-2E6 and VH chimera

The binding abilities of VH-2E6 and VH chimera with AFB1 were determined by antigen immobilized ELISA in this study. The cVH-2E6, cVH-FR2, cVH-Nb26, and SUMO-VH-103 were respectively diluted to the equimolar concentration and then incubated with AFB1-coating antigen of the same concentration. The results revealed that the OD450nm of VH-2E6 to bind with AFB1-OVA (0.30 ± 0.01) was close to the PBS control (0.16 ± 0.02). While an enhancement on absorbance at 450 nm was observed as 0.85 ± 0.10, 0.79 ± 0.03, and 2.13 ± 0.06 for cVH-FR2, cVH-103, and cVH-Nb26, respectively (Fig. 6A). Compared with VH-2E6, all cVH chimera showed improved binding abilities with AFB1. Devoid of light chain, VHs always have demonstrated weak-binding affinities with antigens, which was also observed in this study. The residues on the surface area of VH/VL might influence the antibody-antigen binding. The enhancement of the antigen-binding ability of cVH-Nb26 with AFB1 might be largely attributed to the grafting CDR3 of anti-AFB1 VHH Nb26. Anti-AFB1 Nb26 had a performance with IC50 of 0.754 ng/mL and a linear range from 0.117 to 5.676 ng/mL in a competitive ELISA (He et al. 2014). Through CDR grafting, the transfer of antibody affinity and affinity mutation could be partly achieved. Although at least 20–33% of the residues within CDRs, especially CDR3, were required for the antibody to effectively bind with the antigen (Padlan 1994), the VH template and participation of other regions in antigen binding should be taken into account in vitro affinity maturation (Fanning and Horn 2011).

Binding abilities of VH-2E6 and cVHs against AFB1. A Direct ELISA for the binding of VH-2E6 and cVHs expressed from E. coli systems with AFB1-coating antigens; B the competitive inhibition curves cVH-Nb26 derived from E. coli and Pichia pastoris expression systems against AFB1. Each value represented the mean ± SD of three replicates

IcELISA development for AFB1 detection

To compare the influences of expression systems on AFB1-binding abilities, cVH-Nb26 was obtained respectively from the expression system of E. coli, and Pichia pastoris was used to develop icELISA to assess the competitive binding with AFB1. In icELISA, a series of AFB1 concentrations were diluted and added to the AFB1-coated plate, followed by the optimized concentration of cVH-Nb26. The icELISA employed by cVH-Nb26 expressed in E. coli showed an IC50 of 1.29 µg/mL with a LOD of 0.04 µg/mL, indicating that refolded cVH-Nb26 still had a binding ability with AFB1. The sensitivity of icELISA using camelization of murine VH (cVH-Nb26) expressed in E. coli performed 38-fold better than that observed using scFv 2E6, which was about 50 µg/mL of AFB1 (Liu et al. 2015). For cVH-Nb26 produced in yeast, the sensitivity and LOD of icELISA were 2.39 µg/mL and 0.62 µg/mL, respectively (Fig. 6B). The results revealed that cVH-Nb26 expressed in Pichia pastoris showed a lower antigen-binding capacity, which has also been demonstrated in some cases (Ezzine et al. 2012). The cross-reactivities of cVH-Nb26-based ELISA were not observed with AFB1 analogs (AFB2, AFG1, AFG2, and AFM1) at 4 µg/mL. The AFB1-binding bias of cVH-Nb26 was observed between the different expression systems, which might be attributed to the addition of N-linked or O-linked oligosaccharides in yeast, even if the protein is not glycosylated by its native host (Liu and Huang 2018). In spite of this, the sensitivity of icELISA using cVH-Nb26 from yeast expression performed 20-fold better than that by scFv 2E6. Although the AFB1-affinity of cVH-Nb26 was in a measuring range of µg/mL, which cannot meet the application requirement in the present form, the camelized, murine strategy was proven to be effective for anti-AFB1 antibody preparation in vitro.

In order to characterize and simulate the binding abilities with AFB1, cVH-2E6 was homology modeling for molecular docking. The model of 5XCX.1.A was used as a structure template. The Ramachandran plots for cVH-Nb26 with more than 90% of residues in common in the allowed region were an indication of good protein folding and high quality structures (Fig. S2). In molecular docking analysis, cVH-Nb26 was folded as a groove, the “binding pocket” could bind to AFB1 (Fig. 7A). The cVH-Nb26 was predicted to bind with AFB1 by conventional hydrogen bonds via Ser36 (Fig. 7B), and π-sigma/π-π stacked interactions via Thr50 and Tyr59, respectively. The residue of Ser36 is distributed in FR2 regions, indicating the FR2 region of camelized, murine VHs, showed great influences on the antigen binding and its biophysical behaviors.

VHHs are promising immunoreagents for AFB1 monitoring in food and environmental contamination, due to their excellent properties, including small size, high solubility, high stability, and ease to be manipulated genetically. However, the management of large camelid animals might be the most consideration for VHH production. Specific facilities for camelid housing and a professional veterinarian for their immunizations should be required (Bever et al. 2016). Meanwhile, the affinities of VHHs are dependent to the camelid animal responses of IgG2 or IgG3 subclass to the immunogen. Therefore, a camelized, murine VH is a great strategy to enhance the antigen affinity of VH and used to develop an immunoassay for AFB1 detection. In this study, anti-AFB1 camelized, murine VHs were prepared and then used to analyze the AFB1-VH/cVHs interactions. The icELISA results showed half of cVH-Nb26 produced in E. coli and Pichia pastoris binding with AFB1-coating antigen was inhibited at 1.29 μg/mL and 2.39 μg/mL of AFB1, respectively. Although the sensitivity cannot meet the requirement for application, it performed more than 20-fold better than the original anti-AFB1 scFv. This study also indicated that a camelid CDR3 region was an important role in antibody expression and antigen-binding. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research to prepare the camelized, murine VHs against AFB1 in vitro and used to develop an immunoassay. This work provides a systematical strategy to VH camelization against mycotoxin AFB1 and also helps to better understand the AFB1-antibody-binding mechanism.

Abbreviations

- CDRs:

-

Complementarity-determining regions

- cVHs:

-

Camelized, murine VH chimera

- FRs:

-

Framework regions

- scFv:

-

Single-chain fragment variable

- VHH:

-

Variable domain of heavy chain antibody

- VH:

-

Variable region of heavy chain

- VL:

-

Variable region of light chain

References

Bever CS, Dong J, Vasylieva N, Barnych B, Cui Y, Xu Z, Hammock BD, Gee SJ (2016) VHH antibodies: emerging reagents for the analysis of environmental chemicals. Anal Bioanal Chem 408:5985–6002

Desmyter A, Decanniere K, Muyldermans S, Wyns L (2001) Antigen specificity and high affinity binding provided by one single loop of a camel single-domain antibody. J Biol Chem 276:26282–26290

Ding L, Wang Z, Zhong P, Jiang H, Zhao Z, Zhang Y, Ren Z, Ding Y (2019) Structural insights into the mechanism of single domain VHH antibody binding to cortisol. Febs Lett 593(11):1248–1256

Dixon-Holland DE, Pestka JJ, Bidigare BA, Casale WL, Warner RL, Hart RBP, LP, (1988) Production of sensitive monoclonal antibodies to aflatoxin B1 and aflatoxin M1 and their application to ELISA of naturally contaminated foods. J Food Prot 51:201–204

Ebersole JL, Frey DE, Taubman MA, Smith DJ (1980) An ELISA for measuring serum antibodies to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontal Res, 15, 621-632

Ebersole JL, Frey DE, Taubman MA, Smith DJ. (1985) An ELISA for measuring serum antibodies to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodont Res 15:621–632

Ezzine A, Adab SME, Bouhaouala-Zahar B, Hmila I, Baciou L, Marzouki MN (2012) Efficient expression of the anti-AahI’ scorpion toxin nanobody under a new functional form in a Pichia pastoris system. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 59:15–21

Fanning SW, Horn JR (2011) An anti-hapten camelid antibody reveals a cryptic binding site with significant energetic contributions from a nonhypervariable loop. Protein Sci 20(7):1196–1207

Fridy PC, Li Y, Keegan S, Thompson MK, Nudelman I, Scheid JF, Oeffinger M, Nussenzwerig MC, Fenyö D, Chait BT, Rout MP (2014) A robust pipeline for rapid production of versatile nanobody repertoires. Nat Methods 11:1253–1260

Gathumbi JK, Usleber E, Märtlbauer E (2001) Production of ultrasensitive antibodies against aflatoxin B1. Lett Appl Microbiol 32(5):349–351

Hamers-Casterman CAT, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hammers C, Songa EB, Bendahman N, Hammers R (1993) Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature 363:446–448

He T, Wang Y, Li P, Zhang Q, Lei J, Zhang Z, Ding X, Zhou H, Zhang W (2014) Nanobody-based enzyme immunoassay for aflatoxin in agro-products with high tolerance to cosolvent methanol. Anal Chem 86:8873–8880

International Agency for Research on Cancer (1993) IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; Lyon, France

Kabat E, Wu TT, Reid-Miller M, Perry HM, Kay S, Gottesman CF (1992) Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. In DIANE Publishing Darby, PA

Karbalaei M, Rezaee SA, Farsiani H (2020) Pichia pastoris: a highly successful expression system for optimal synthesis of heterologous proteins. J Cell Physiol 235(9):5867–5881

Kim DY, Hussack G, Kandalaft H, Tanha J (2014) Mutational approaches to improve the biophysical properties of human single-domain antibodies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1844:1983–2001

Kim HJ, Mccoy MR, Majkova Z, Dechant JE, Gee SJ, Tabares-Da RS, González-Sapienza GG, Hammock BD (2012) Isolation of alpaca anti-hapten heavy chain single domain antibodies for development of sensitive immunoassay. Anal Chem 84:1165–1171

Kumar P, Mahato DK, Kamle M, Mohanta TK, Kang SG (2016) A global concern for food safety, human health and their management. Front Microbiol 7:2170

Li P, Zhang Q, Zhang W, Zhang J, Chen X, Jiang J, Xie L, Zhang D (2009) Development of a class-specific monoclonal antibody-based ELISA for aflatoxins in peanut. Food Chem 115:313–317

Liu A, Ye Y, Chen W, Wang X, Chen F (2015) Expression of VH-linker-VL orientation-dependent single-chain Fv antibody fragment derived from hybridoma 2E6 against aflatoxin B1 in Escherichia coli. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 42:255–262

Liu Y, Huang H (2018) Expression of single-domain antibody in different systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(2):539–551

Li W, Schäfer A, Kulkarni SS, Liu X, Martinez DR, Chen C, Sun Z, Leist SR, Drelich A, Zhang L, Ura ML, Berezuk A et al (2020) High potency of a bivalent human VH domain in SARS-CoV-2 animal models. Cell 183:429–441

Li Z, Dong J, Vasylieva N, Cui Y, Wan D, Hua X, Huo J, Yang D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD (2021) Highly specific nanobody against herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid for monitoring of its contamination in environmental water. Sci Total Environ 753:141950

Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ (2009) AutoDock4 and autoDock tools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30(16):2785–2791

Muyldermans S (2020) Applications of nanobodies. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 9:1–12

Padlan EA (1994) Anatomy of the antibody molecule. Mol Immunol 31:169–217

Rangnoi K, Choowongkomon K, O’Kennedy R, Rüker F, Yamabhai M (2018) Enhancement and analysis of human anti-aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) scFv antibody-ligand interaction using chain shuffling. J Agric Food Chem 66:5716–5722

Raters M, Matissek R (2008) Thermal stability of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A. Mycotoxin Res 24(3):130–134

Roh J, Byun SJ, Seo Y, Kim M, Lee JH, Kim S, Lee Y, Lee KW, Kim JK, Kwon MH (2015) Generation of a chickenized catalytic anti-nucleic acid antibody by complementarity-determining region grafting. Mol Immunol 63:513–520

Shriver-Lake LC, Zabetakis D, Goldman ER, Anderson GP (2017) Evaluation of anti-botulinum neurotoxin single domain antibodies with additional optimization for improved production and stability. Toxicon 135:51–58

Silva FAD, Santa-Marta M, Freitas-Vieira A, Mascarenhas P, Barahona I, Moniz-Pereira J, Gabuzda D, Goncalves J (2004) Camelized rabbit-derived VH single-domain intrabodies against Vif strongly neutralize HIV-1 infectivity. J Mol Biol 340:525–542

Vincke C, Loris R, Saerens D, Martinez-Rodriguez S, Muyldermans S, Conrath K (2009) General strategy to humanize a camelid single-domain antibody and identification of a universal humanized nanobody scaffold. J Biol Chem 284:3273–3284

Wang J, Bever CRS, Majkova Z, Dechant JE, Yang J, Xu GSJ, T, Hammock BD, (2014) Heterologous antigen selection of camelid heavy chain single domain antibodies against tetrabromobisphenol A. Anal Chem 86:8296–8302

Wang J, Majkova Z, Bever CRS, Yang J, Gee SJ, Li J, Xu T, Hammock BD (2015) One-step immunoassay for tetrabromobisphenol A using camelid single domain antibody and alkaline phosphatase fusion protein. Anal Chem 87(9):4741–4748

Ward ES, Güssow D, Griffiths AD, Jones PT, Winter G (1989) Binding activities of a repertoire of single immunoglobulin variable domains secreted from Escherichia coli. Nature 341:544–546

Wu L, Li G, Xu X, Zhu L, Huang R, Chen X (2019) Application of nano-ELISA in food analysis: recent advances and challenges. TrAC-Trend Anal Chem 113:140–156

Wu S, Luo J, O’Neil KT, Kang J, Lacy ER, Canziani G, Baker A, Huang M, Tang QM, Raju TS, Jacobs AJ, Teplyakov A et al (2010) Structure-based engineering of a monoclonal antibody for improved solubility. Protein Eng Des Sel 23(8):643–651

Xue Z, Zhang Y, Yu W, Zhang J, Wang J, Wan F, Kim Y, Liu Y, Kou X (2019) Recent advances in aflatoxin B1 detection based on nanotechnology and nanomaterials-A review. Anal Chim Acta 1069:1–27

Ye Y, Liu A, Wang X, Chen F (2016) Spectra analysis of coating antigen: a possible explanation for difference in anti-AFB1 polyclonal antibody sensitivity. J Mol Struct 1121:74–79

Zhang F, Liu B, Zhang Y, Wang J, Lu Y, Deng J, Wang S (2019) Application of CdTe/CdS/ZnS quantum dot in immunoassay for aflatoxin B1 and molecular modeling of antibody recognition. Anal Chim Acta 1047:139–149

Zhang X, Song M, Yu X, Wang Z, Ke Y, Jiang H, Li J, Shen J, Wen K (2017) Development of a new broad-specific monoclonal antibody with uniform affinity for aflatoxins and magnetic beads-based enzymatic immunoassay. Food Control 79:309–316

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601539), National Institute of Environmental Health Science Superfund Research Program (P42 ES004699), and National Institute of Health RIVER Award (R35 ES030443-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. Qian Pang and Yanhong Chen give equal contributions to this work. Conceptualization, supervision: Jia Wang. Methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft: Qian Pang, Yanhong Chen. Methodology: Hina Mukhtar, Jing Xiong. Resources: Xiaohong Wang, Ting Xu. Writing—review and editing, funding acquisition: Bruce D. Hammock, Jia Wang. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, Q., Chen, Y., Mukhtar, H. et al. Camelization of a murine single-domain antibody against aflatoxin B1 and its antigen-binding analysis. Mycotoxin Res 38, 51–60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-021-00433-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-021-00433-z