Abstract

Background

The competence of the person delivering person-to-person behaviour change interventions may influence the effectiveness of the intervention. However, we lack a framework for describing the range of competences involved. The objective of the current work was to develop a competency framework for health behaviour change interventions.

Method

A preliminary framework was developed by two judges rating the relevance of items in the competency framework for cognitive behaviour therapies; adding relevant items from reviews and other competency frameworks; and obtaining feedback from potential users on a draft framework. The Health Behaviour Change Competency Framework (HBCCF) was used to analyse the competency content of smoking cessation manuals.

Results

Judges identified 194 competency items as relevant, which were organised into two domains: foundation (12 competency topics comprising 56 competencies) and behaviour change (12 topics, 54 competencies); several of the 54 and 56 competencies were composed of sub-competencies (84 subcompetencies in total). Smoking cessation manuals included 14 competency topics from the foundation and behaviour change competency domains.

Conclusion

The HBCCF provides a structured method for assessing and reporting competency to deliver behaviour change interventions. It can be applied to assess a practitioner’s competency and training needs and to identify the competencies needed for a particular intervention. To date, it has been used in self-assessments and in developing training programmes. We propose the HBCCF as a practical tool for researchers, employers, and those who design and provide training. We envisage the HBCFF maturing and adapting as evidence that identifies the essential elements required for the effective delivery of behaviour change interventions emerges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of behaviour in determining health outcomes has led to the development of behaviour change interventions designed to improve outcomes by changing the behaviour of people in general, clinical populations, or healthcare professionals. Behaviour change interventions take many forms, and the competencies required to deliver these different forms of intervention are likely to differ widely; for example, delivering a self-help weight management leaflet requires a lesser level of competency than that required to change dietary and sedentary behaviours in a morbidly obese diabetic patient. Furthermore, behaviour change interventions are delivered by health professionals from a variety of disciplines and in a wide range of settings [1]. Practitioners trained in these disciplines may vary greatly in how competent they are to deliver behaviour change interventions. They have different training and, while there is likely to be some shared competencies over different disciplines, there is no framework for describing these competencies. In this paper, we focus on behaviour change interventions delivered person-to-person to individuals or small groups and outline the pragmatic development of a framework of the competencies involved in their delivery by health or other professionals. Interventions using other, non-personalised, modes of delivery [2, 3] are also effective in achieving behaviour change [4] but require other competences outside the scope of the current paper.

The competency of the person delivering an intervention may, in part, determine its effectiveness. Meta-analyses of behaviour change interventions frequently note heterogeneity in the findings and explore possible sources of this heterogeneity [5,6,7,8]. The availability of an agreed taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) means the role of BCTs in this heterogeneity can be explored and effective BCTs identified [9]. Unfortunately, there is no standard method of reporting the competency of the persons delivering the intervention and it is therefore difficult to ascertain whether this might also explain at least some of the variance in outcomes from behaviour change interventions. That said, there is evidence that the quality of delivery of behaviour change interventions impinges on their effectiveness; Lorencatto and colleagues found that smoking cessation interventions were more effective if the person delivering the intervention ensured that goal-setting was delivered well, but, while they described effective delivery, they did not offer guidance on how to achieve this quality [10]. Several studies also note that interventions may be more effective when delivered by a particular profession: for example, Hartman-Boyce found that weight loss programmes were more effective if a dietician was involved in delivery [11]. On the other hand, An et al. (2008) found that having more than one profession involved was important for success in smoking cessation [1]. It is plausible that having more than one profession involved ensured a wider range of competencies.

The importance of the competency of the person delivering an intervention is increasingly recognised. The TIDieR checklist for the reporting of interventions [12] requires the description of the theoretical processes employed in an intervention, the behaviour change content, and the multiple requirements for its delivery. TIDieR requires not only a description of the person delivering the intervention but also a description of any specific training given. Behaviour change interventions have been described as having two broad components, behaviour change techniques and form-of-delivery, i.e. the way the intervention is delivered [13, 14], which includes professional competencies such as communication style [15]. The important role of interpersonal competencies in behaviour change interventions is increasingly recognised [16] and some have even suggested that interpersonal style might best be considered a behaviour change technique [17].

Competency-based training and assessment is used by a variety of health professions but some of these competencies may be specific to a particular profession. However, behaviour change interventions are delivered by a wide range of disciplines and we therefore need a framework that works across disciplines. Based on consultation with a wide range of disciplines and with national policy-makers responsible for health-related behaviour change, and on our experience, (a) in research on behaviour change interventions including delivery and evaluation in randomised controlled trials, (b) in practice, both in delivering and in managing staff delivering person-to-person behaviour change interventions, and (c) in policy as advisers to national policy-makers and civil servants tasked with implementing policy, we propose that such a framework might serve the following purposes:

-

Implementation: More precise reporting of competencies of individuals delivering behaviour change interventions and therefore more accurate implementation of effective behaviour change interventions.

-

Evidence synthesis: Analysis of the impact of competency on effectiveness of RCTs and in evidence synthesis resulting in better analyses of sources of heterogeneity of results.

-

Competence across behaviours and contexts: Identification of generic competencies that are relevant for changing a wide range of behaviours to inform the movement of staff competent in delivering behaviour change interventions for one behaviour or context to transfer to delivering behaviour change interventions effectively for a different behaviour or in a different setting.

-

Competencies for behaviour change interventions of different complexity: Identification of competencies needed for behaviour change interventions of increasing degrees of complexity to allow the possibility that staff with lower levels of competence may deliver simple behaviour change interventions while ensuring that complex interventions are only delivered by more competent staff.

-

Job descriptions: Specification, by employers, of the competencies required for particular roles and potential employees able to choose jobs matched to their own competencies.

-

Staff selection: Appointment of staff with appropriate competency to deliver behaviour change interventions through the assessment of the competences of available candidates.

-

Training needs: Specification of training needs for staff delivering behaviour change interventions so that individuals can find appropriate training opportunities or can by guided to such resources by their career guidance personnel.

-

Training programmes: Specification of the necessary components of training programmes to ensure that the full range of competences are addressed and at the level of complexity appropriate for the staff being trained.

We therefore aimed to develop a behaviour change intervention competency framework to be used in assessing competency to deliver behaviour change interventions by practitioners working directly with clients and patients. This work was undertaken while the authors were on secondment with the Health Directorate of the Scottish Government. It forms a pragmatic response to the expressed need of the Health Directorates (including policy leads for alcohol, smoking, obesity, and drugs) for such a competency framework. Our aim was to develop a working framework that could be updated as required, e.g. through the inclusion of additional competencies and the removal of unnecessary competencies, as additional evidence of the competencies needed to deliver behaviour change interventions accumulates.

It might appear desirable to conduct a content analysis of competence requirements cited in published reports of behaviour change interventions; this proved impossible as, while these reports sometimes made reference to the disciplines of those delivering the interventions, they made little reference to competences required. We therefore took as our starting point the existing competency framework which was nearest to our requirements of describing competence to deliver behaviour change interventions in a person-to-person context, the CBT competency framework for depression and anxiety disorders [18]. CBT was derived directly from behavioural therapy, where the target was to change behaviour directly. The CBT competency framework reflects this and deals with both personal psychological change and behaviour change in interventions delivered person-to-person. Nevertheless, since the CBT framework was planned for use in interventions where behaviour change may not be required, and its constituent techniques for change have a psychological focus, e.g. Socratic questioning, the structure and focus of the framework required adaptation to be suitable for behaviour change interventions.

The aims of this study were to:

-

1.

Develop a health behaviour change competency framework based on the CBT competency framework.

-

2.

Illustrate the use the framework to analyse the competency content of behaviour change interventions, using smoking cessation manuals as the example.

Method

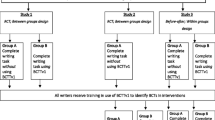

The research was conducted as two studies, which matched the two aims.

Study 1: Development of a Health Behaviour Change Competency Framework Based on the CBT Framework

The development of the framework involved four phases: identifying relevant items from the CBT competency framework; identifying additional items from literature (research reports and training manuals) and experts in the area; structuring the resulting items; and obtaining and incorporating feedback from stakeholders.

-

i.

The CBT competency framework consisted of five competency domains [18]. Two registered health psychologists (DD and MJ) independently classified each of the CBT domains as relevant or not to behaviour change interventions. The individual competencies within each behaviour change intervention relevant domain were then each judged as relevant or not relevant to behaviour change interventions delivered person-to-person, to an individual or in small groups. Agreement was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient two-way mixed model with measure of consistency, to give the equivalent to Cohen’s weighted kappa [19] and then disagreements were resolved by discussion.

-

ii.

The resulting list of competencies was developed and expanded in an iterative process. Additional competencies relevant to health behaviour change were identified by consulting systematic reviews [7, 20,21,22,23] of behaviour change interventions and health psychologists working in the area of behaviour change (members of the British Psychological Society Division of Health Psychology – Scotland). Of particular importance was the need to include competency to deliver behaviour change techniques (BCTs)Footnote 1 [9]. A content analysis of a national competency framework and accompanying training manuals for alcohol brief interventions identified generic professional and basic behaviour change competencies [24, 25].

-

iii.

The list of competencies generated was organised using the CBT competency framework as an outline structure in which each competency item was grouped into a competency topic, which in turn were grouped into higher order competency domains. The structure was adjusted where the health behaviour change competencies differed from those for CBT.

-

iv.

A preliminary framework (incorporating a preliminary version of the Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy v1 [9])1 was presented for formal input and feedback to a wide range of the potential national policy and practitioner users including the National Scottish Government Department of Health policy leaders for health improvement (including policy leaders for healthy living and screening; obesity; smoking and substance abuse; sexual health; alcohol); the Head of Learning and Improvement for NHS Scotland; Programme Director NHS Education Scotland and the section head of NHS Education Scotland with responsibility for training the workforce to deliver behaviour change; Public Health Consultants responsible for regional delivery of behaviour change interventions from rural and urban health boards; and health and clinical psychology practitioners working across three health boards. In addition, the HBCCF was also presented to a variety of stakeholders (practitioners and training leads from a variety of health boards) and feedback received from them regarding whether the HBCCF would be useful for them, what aspects would be most useful, whether the HBCCF was missing important information, and whether any aspect of the HBCCF was unclear. We also consulted health psychology trainees and health psychology conference attenders (British Psychological Society Division of Health Psychology – Scotland Annual Scientific Conference via a plenary presentation and a structured audience feedback session). Stakeholders consulted were aware that their responses would inform the publication of the HBCCF.

-

v.

To facilitate integration with existing competency frameworks used by UK public sector employees, the competencies described in the HBCCF were mapped across to the Knowledge and Skills Framework [26] (KSF). This was completed by one judge (DD).

Study 2: Illustrating Use of the Framework to Analyse the Competency Requirements of Behaviour Change Interventions

The HBCCF was used to analyse the competency content of ten smoking cessation manuals used in interventions in the UK and USA and included in a systematic review [22]. Coding was conducted for each competency topic and grouped by competency domain by two coders (MJ and DD) independently. Agreement was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results

Study 1

The CBT framework is comprised of five competency domains of which, in the first phase, three were judged to be potentially relevant to behaviour change interventions namely, generic therapeutic, basic CBT, and metacompetency domains. Two domains were judged to be not relevant, namely specific behavioural and cognitive therapy techniques and problem-specific competencies. The behavioural and cognitive therapy techniques domain described general therapy competencies relevant to the delivery of CBT, for example, guided discovery and Socratic questioning, applied relaxation, and applied tension. The problem-specific competency domain described competencies required to deliver particular interventions for specific psychological conditions, e.g. Resick model of PTSD [27, 28], Beck’s cognitive therapy for depression [29].

The three domains judged as relevant to behaviour change interventions describe 31 competency areas; 26 were judged to contain competencies relevant to health behaviour change (kappa = 1). The 26 competency areas are comprised of 267 specific competencies of which 152 were identified as relevant (kappa equivalent = 0.74). Phase ii identified an additional 42 specific competencies. Some parts of the structure of the CBT framework were retained and the 194 individual competency items relevant to behaviour change interventions were structured into two domains each with 12 topics (see Table 1). Phase iv feedback did not alter the structure but resulted in rephrasing some items to aid intelligibility for multiple disciplines. The resulting HBCCF consists of two domains: foundation competencies organised in 12 topics with a total of 56 competencies and behaviour change competencies organised in 12 topics with a total of 54 competencies. The 56 and 54 competencies of the foundation and behaviour change competency domains are themselves comprised of sub-competencies that make up the total 194 individual competency items of the HBCCF (see Table 1).

The full list of competencies within each domain is provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table 1) but here, we illustrate the contents of a single foundation and a single behaviour change topic (see Table 2).

In order for the HBCCF to be useful to UK public sector employers, in phase v, the competencies were mapped to the Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF), which they use. Table 3 shows a summary of the mapping between the HBCCF and the KSF. The detailed mapping of each HBCCF competency to the KSF is contained in the Electronic Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table 1).

Study 1 resulted in the Health Behaviour Change Competency Framework (HBCCF) which was made available for use in the Scottish National Health Service including being published on the Government website http://www.healthscotland.com/documents/4877.aspx.Footnote 2

Study 2

The competency topics identified in the behavioural support for smoking cessation manuals are shown in Table 4. Kappa for agreement was 0.65. Each manual contains a range of competencies with interventions that delivered individual behavioural support describing more competencies than the others.

Discussion

The work we describe here has developed and illustrated the use of a HBCCF.

As outlined in the “Introduction” section, there are many reasons for needing a competency framework for the delivery of behaviour change interventions for both research and practical applications. Nevertheless, there is no agreed method of developing such a framework. As a starting point, we used a well-developed framework, based on evidence of effectiveness, which we considered to be the most closely related to our current aims as it addressed changes in behaviour and thinking required to achieve personal change. This was confirmed in the first phase of study 1, where there was complete agreement on the initial judgement carried out at the level of labels for groups of related individual competencies. This judgement task was very straightforward because the activities were rather obviously relevant to the delivery of behaviour change interventions, e.g. ‘knowledge of, and ability to operate within, professional and ethical guidelines’ or were very obviously not, e.g. ‘applied tension and applied relaxation’, i.e. competencies that were very much CBT related. Our task at this stage was to decide whether each group of competencies was potentially relevant to our purposes. This was a simple task that resulted in perfect agreement.

We also found substantial agreement that 152 of the individual competence items of the CBT framework were relevant for HBCCF. This level of agreement does not simply reflect shared working of the two coders as it was conducted independently prior to discussion and subsequent stages in developing HBCCF did not add further competences that might have been found in the CBT framework.

However, the competencies identified in this way mainly covered the competencies to reach the point of delivering the active ingredients of the intervention but did not address competency to deliver actual BCTs. Thus, it became apparent that a richer source of active behaviour change methods was required.

The competencies derived from the CBT framework were classified into two domains. The first, foundation competencies, addresses the knowledge and skills that might be necessary for anyone delivering a person-to-person service, for example including surgeons and lawyers, as they deal with the legal ethical and professional frameworks and with the effective, non-discriminatory communication needed to engage the client and continue to work with them. The second, behaviour change competencies, deals with knowledge and skills relevant to delivering services for personal change, including assessment and intervention planning before delivery of active ingredients, i.e. BCTs; some of these competencies would be relevant for any intervention designed to enable the recipient to make change while others are more specific to behaviour change. The foundation and behaviour change competencies were modified in the third phase of development by feedback from potential users but we would expect this to be a continuing process of modification, including additions and removals.

In summary, our approach was to begin with expert consensus and to offer a framework based on this consensus. This consensus-based framework should be explored and tested by the wider academic community as well as by those tasked with developing, delivering, and assessing training. We recognise that there is always a decision to be made as to at what point do you stop any development process and publish the outcomes of that development, in this case the HBCCF. Our approach was to be advised by our stakeholders as to when the framework was at a stage of being credible, acceptable, and feasible to use by those using it. At that stage, the government published the framework for use via their website. Here, our aim is to describe the development of the HBCCF and to make it available for wider scrutiny and evaluation.

The HBCC was developed using an early version of the BCT taxonomy that was later published as the BCTTv1 [9]. BCTv1 was considered suitable as it is widely used for describing the active content of behaviour change interventions. We also anticipate that the HBCCF will continue to require updating as that taxonomy matures and is informed by additional evidence. We anticipate improvements to HBCCF with continued use.

Study 2 illustrates how the competencies required for an intervention can be specified leading to the appointment of staff with the required skills for the specific intervention. In a research context, the HBCCF allows more precise description of the training and skills of those delivering an intervention as required by TIDieR under the heading ‘WHO’ [12] and may also assist in explaining differences in effectiveness between different health behaviour change interventions. That said, the modest interrater agreement obtained in the current study indicates that the terminology used to describe competencies could be improved. The ability to code reliably the behaviour change content of behaviour change interventions has benefitted enormously from the publication of the BCTTv1, which provides a shared and agreed terminology for BCTs. This shared language enables the BCT content of behaviour change interventions to be described with precision and for that content to be recognised reliably. The development of an equivalent agreed terminology for competencies to deliver behaviour change interventions would undoubtedly be useful.

Other related competency frameworks have been developed. The NHS Yorkshire and Humber ‘Prevention and Lifestyle Behaviour Change’ framework [30] describes competencies for a wide range of lifestyle change but only a small part of this framework addresses interventions to change behaviour. Unfortunately, the methodology for the development of the framework is not described in detail; however, many of the items included overlap with the HBCCF. The competence framework for psychological interventions with people with persistent physical health conditions [31] aims to define competencies for work with a more restricted population, dealing with competencies in working with people with long-term conditions. As a result, it has some overlap insofar as that work involves behaviour change but it does not address change in people without an ongoing clinical condition. It was developed by discussion and consensus rather than by the independent content analysis and coding methods used to develop the HBCCF. However, its development benefitted from the inclusion of individuals from a variety of disciplines working with people with long-term conditions, including practitioners and researchers from general practice, secondary and tertiary referral, academia, and those responsible for the training and development of the NHS workforce. It identifies 31 competency topics organised into six competency domains, plus one domain that specifies specific interventions for people with long term conditions (examples of six CBT-based interventions and one psychodynamic interpersonal therapy are provided). Neither of these two frameworks was developed with reference to the delivery of the active component of behaviour change interventions, namely BCTs.

More recently, Public Health England, the national body responsible for public health in England, has been developing a behaviour change development framework (https://behaviourchange.hee.nhs.uk/) for use in training and in planning developments in health and social care. This framework has incorporated much of the HBCCF but additionally has classified competences according to the different levels of competence that might be required. For example, the lowest level (‘very brief interventions for service users with a primarily administrative need’) includes ‘initiate a discussion about health behaviours’ which is similar to HBCCF foundation competence F5.1 ‘ability to initiate a discussion about potential health behaviour problems’, the next level (‘brief and extended interventions for service users with a specific health or social care need’) includes ‘agree goals for the interventions and ensure they are realistic, attainable, timely and measurable’) comparable with HBCCF behaviour change competency domain BC4 ‘ability to agree goals for the intervention’, and the top-level (‘high-intensity interventions for service users with primarily complex behaviour related needs’) includes ‘adapt interventions in response to service user feedback’ which is similar to foundation domain competency F8 ‘capacity to adapt intervention to client feedback’. At an early stage, HBCCF competences were classified into different levels of intensity of the intervention (http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/4877-Health_behaviour_change_competency_framework.pdf) but this should be repeated using the improved definitions of intervention intensity developed by Public Health England.

Like the NHS Yorkshire and Humber framework, the HBCCF was created to meet the needs of health service delivery. The HBCCF was developed for the Health Directorate of the Scottish Government. The urgent need for this framework was demonstrated by the willingness of policy-makers, training designers, and practitioners to engage in the consultation and feedback processes. The HBCCF has been used widely to develop and implement training on health behaviour change for health professionals across the UK. For example, the utility of competency frameworks, with the HBCCF as the exemplar framework, to structure and evaluate staff training to ensure their competence to deliver behaviour change interventions has been recognised in national guidance [32]. The HBCCF is also currently being used by the National Health Service Education Scotland to develop a behaviour change training programme for NHS staff and is being used by the Scottish Diabetes Group to improve the consultation and behaviour change skills of health professionals working in the area of diabetes. The use of the framework at this stage by training leads simply demonstrates the urgent need for such a framework. The HBCCF was found to be useful and, crucially, was available for use when the NHS Education Scotland needed such a framework. Ideally, more development would have been beneficial but in practical contexts an adequate framework is better than no framework and the use of an explicit framework allows for future improvements in a cumulative manner. The HBCCF also provided an informative framework during the development of a competency framework for psychological interventions in physical health [31].

In planning further work, we anticipated that the HBCCF might be useful in self-assessment by practitioners deciding on training they should undertake or employment they should seek. We are therefore working on an online self-assessment of HBCCF competencies. In addition, we recognise that interventions may require different levels of competence and that health professionals from different disciplines or at different stages in their training may require a different level of competence to deliver behaviour change interventions in their work context. We are therefore examining competences at different levels and stages of professional development.

Conclusions

A framework for describing the competencies required to deliver health behaviour change is of considerable importance in both research and practical contexts to ensure that intervention delivery is both adequate and reportable. We describe the pragmatic development of the HBCCF for behaviour change interventions delivered person-to-person based on an existing framework (CBT competency framework) and with reference to an early version of the BCTTv1, amplified by examination of relevant research and application literatures. The two domains (foundation and behaviour change) describe a comprehensive set of competencies which have proved useful in practical situations and are illustrated here for smoking cessation interventions. In sum, the HBCCF is a usable, useful framework but one which will be adapted with use.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Notes

At the time the HBCCF was being developed the BCTTv1 was not yet finalised and published. Therefore, a preliminary version of the taxonomy was used to inform judgements about the relevance of competencies to deliver behaviour change interventions, an important active ingredient of which is BCTs.

The HBCCF published by the NHS Scotland contains an early version of the taxonomy of BCTs. We presented the BCTs to the NHS Scotland in the form of a 3rd domain to be considered alongside the two competency domains because BCTs are the active components of behaviour change interventions that staff need to be competent to deliver.

Abbreviations

- CBT:

-

cognitive behaviour therapy

- BCTs:

-

behaviour change techniques

- BCTTv1:

-

Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy Version 1

- HBCCF:

-

Health Behaviour Change Competency Framework

- KSF:

-

Knowledge and Skills Framework

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

References

An LC, Foldes SS, Alesci NL, Bluhm JH, Bland PC, Davern ME, et al. The impact of smoking-cessation intervention by multiple health professionals. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:54–60.

Marques MM, Carey RN, Norris E, Evans F, Finnerty AN, Hastings J, et al. Delivering behaviour change interventions: development of a mode of delivery ontology. Wellcome Open Res. 2020; Available from: https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/collections/humanbehaviourchange.

Black N, Williams AJ, Javornik N, Scott C, Johnston M, Eisma MC, et al. Enhancing behavior change technique coding methods: identifying behavioral targets and delivery styles in smoking cessation trials. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(6):583–91.

Black N, Eisma MC, Viechtbauer W, Johnston M, West R, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Variability and effectiveness of comparator group interventions in smoking cessation trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2020.

Avery L, Flynn D, Dombrowski SU, van Wersch A, Sniehotta FF, Trenell MI. Successful behavioural strategies to increase physical activity and improve glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1058–62.

Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Avenell A, Johnston M, MacLennan G, Araújo-Soares V. Identifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity-related co-morbidities or additional risk factors for co-morbidities: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6:7–32.

Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701.

Michie S, Jochelson K, Markham WA, Bridle C. Low-income groups and behaviour change interventions: a review of intervention content, effectiveness and theoretical frameworks. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:610–22.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Lorencatto F, West R, Bruguera C, Brose LS, Michie S. Assessing the quality of goal setting in behavioural support for smoking cessation and its association with outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2015:1–9.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Johns DJ, Jebb SA, Aveyard P. Behavioural weight management review g. effect of behavioural techniques and delivery mode on effectiveness of weight management: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Obes Rev. 2014;15:598–609.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348.

Michie S, Thomas J, Johnston M, Aonghusa PM, Shawe-Taylor J, Kelly MP, et al. The human behaviour-change project: harnessing the power of artificial intelligence and machine learning for evidence synthesis and interpretation. Implement Sci. 2017;12:121.

Michie M, West R, Finnerty AN, Norris E, Wright AJ, Marques MM, et al. Representation of behaviour change interventions and their evaluation: development of the upper level of the behaviour change intervention ontology. Wellcome Trust. 2020; Available from: https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/collections/humanbehaviourchange.

Dombrowski SU, O'Carroll RE, Williams B. Form of delivery as a key ‘active ingredient’ in behaviour change interventions. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:733–40.

Hardcastle SJ, Fortier M, Blake N, Hagger MS. Identifying content-based and relational techniques to change behaviour in motivational interviewing. Health Psychol Rev. 2017;11:1–16.

Hardcastle SJ. Commentary: Interpersonal style should be included in taxonomies of behavior change techniques. Front Psychol. 2016;7(894).

Roth AD, Pilling S. The competencies required to deliver effective cognitive behavioural therapy for people with depression and anxiety disorders. London: Department of Health; 2007.

Hallgren KA. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2012;8:23–34.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27:379–87.

Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1479–98.

Michie S, Churchill S, West R. Identifying evidence-based competences required to deliver behavioural support for smoking cessation. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:59–70.

Ashford S, Edmunds J, French DP. What is the best way to change self-efficacy to promote lifestyle and recreational physical activity? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15:265–88.

NHS Health Scotland. Alcohol Brief Interventions training. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland; 2009.

NHS Education Scotland. Delivery of Alcohol Brief Interventions: A Competency Framework. Edinburgh: NHS Education Scotland; 2010.

Department of Health. The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (NHS KSF) and the Development Review Process. London: Department of Health; 2004.

Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy: veteran/military version: therapist and patient materials manual. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014.

Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims. London: Sage Publications; 1996.

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979.

NHS Education England. Prevention and Lifestyle Behaviour Change: A Competence Framework: NHS Yorkshire and Humberside; 2010. Available from: http://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/docs/Prevention%20and%20Lifestyle%20Behaviour%20Change%20A%20Competence%20Framework.pdf

Roth AD, Pilling S. Competence framework for psychological interventions with people with persistent physical health conditions. 2015. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/pals/research/cehp/research-groups/core/pdfs/Physical_Health_Problems/Physical_Background_Doc.pdf.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Behaviour change: individual approaches (PH49). London: NICE; 2014.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken while we were seconded into the Health Directorates of the Scottish Government. We are grateful to all those who provided input to this work. We would especially like to thank Wilma Reid (Head of Learning and Workforce Development, Health Scotland), Jane Cantrell (Programme Director, Nursing and Allied Health Professional Workforce Development, NHS-Education Scotland), and Tim Warren (Policy Lead, Self-Management and Health Literacy, Scottish Government), all of whom provided feedback on the HBCCF throughout its development. We also extend particular thanks to Professor Ronan O’Carroll (University of Stirling) and Dr. Vivien Swanson (University of Stirling), who, as Chairs of the BPS-Division of Health Psychology Scotland, worked tirelessly to secure the funding for the secondment into the Scottish Government and provided guidance and input to the work throughout.

Funding

Both authors were on part-time secondment to the Health Directorate of the Scottish Government. The secondment was funded by the Health Directorates and the British Psychological Society Division of Health Psychology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the work described herein, the data collection and analyses, all the writing of the HBCC and this report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to Participate

This study did not include primary data collection from human participants.

Ethical Approval

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 716 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dixon, D., Johnston, M. What Competences Are Required to Deliver Person-Person Behaviour Change Interventions: Development of a Health Behaviour Change Competency Framework. Int.J. Behav. Med. 28, 308–317 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09920-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09920-6