Abstract

Purpose

Mild depression has been shown as a precursor and as a consequence of low back pain, even in early phases of acute or subacute pain. Chronic daily life stress as well as dysfunctional pain-related cognitions such as thought suppression (TS) seem to play a role in the pain-depression cycle; however, the mechanisms of these associations are less understood. Experimentally induced TS, conceived as the attempt to directly suppress sensations such as pain, has been shown to paradoxically cause a delayed and non-volitional return of the suppressed thoughts and sensations and to increase affective distress. These dysfunctional processes are supposed to increase under high cognitive load, such as high stress.

Method

In the present cross-sectional study, we for the first time sought to examine a possible interaction between habitual TS and stress on depression in N = 177 patients with subacute low back pain (SLBP), using the following questionnaires: Subscale Thought Suppression from Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, and Kiel Interview of Subjective Situation. A three-way ANOVA was conducted with two groups of TS (high/low), stress (high/low) and sex as independent factors and depression as dependent.

Results

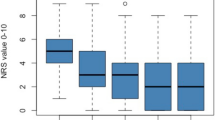

Results indicated a significant three-way interaction with highest depression scores in female patients showing high TS and high stress. Overall main effects for sex and stress indicated higher depression in women and in highly stressed patients.

Conclusion

Our findings support the hypothesis that TS heightens depressive mood under conditions of high cognitive load especially in female patients with SLBP indicating a special vulnerability for depressive mood in women with SLBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

26 December 2017

This article was updated to correct the author names. Family and given names are in the correct order.

References

Poole H, White S, Blake C, Murphy P, Bramwell R. Depression in chronic pain patients: prevalence and measurement. Pain Pract. 2009;9:173–80. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00274.x.

Haggman S, Maher CG, Refshauge K. Screening for symptoms of depression by physical therapists managing low back pain. Phys Ther. 2004;84:1157–66.

Dilling H, Mombour W, Schmidt MH, Schulte-Markwort E, Remschmidt H, editors. Internationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen: ICD-10 Kapitel V (F) klinisch-diagnostische Leitlinien. 10th ed. Bern: Hogrefe; 2015.

Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, Cedraschi C. Clinical update: low back pain. Lancet. 2007;369:726–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60340-7.

Hasenbring M, Marienfeld G, Kuhlendahl D, Soyka D. Risk factors of chronicity in lumbar disc patients. A prospective investigation of biologic, psychologic, and social predictors of therapy outcome. Spine. 1994;19:2759–65.

Melloh M, Elfering A, Käser A, Salathé CR, Barz T, Aghayev E, et al. Depression impacts the course of recovery in patients with acute low-back pain. Behav Med. 2013;39:80–9. doi:10.1080/08964289.2013.779566.

Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine. 2000;25:1148–56.

Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Grant I, Patterson TL, Garfin SR. Depressed mood in chronic low back pain: relationship with stressful life events. Pain. 1988;35:47–55.

Turk DC, Okifuji A, Scharff L. Chronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohorts. Pain. 1995;61:93–101.

Hasenbring M. Endurance strategies—a neglected phenomenon in the research and therapy of chronic pain? Schmerz. 1993;7:304–13. doi:10.1007/BF02529867.

Hasenbring MI, Hallner D, Rusu AC. Fear-avoidance- and endurance-related responses to pain: development and validation of the avoidance-endurance questionnaire (AEQ). Eur J Pain. 2009;13:620–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.001.

Hasenbring M, Rusu AC, Turk DC, editors. From acute to chronic back pain: risk factors, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Wegner DM, Schneider DJ, Carter SR, White TL. Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:5–13.

Wegner DM. Ironic processes of mental control. Psychol Rev. 1994;101:34–52.

Cioffi D, Holloway J. Delayed costs of suppressed pain. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64:274–82.

Masedo AI, Esteve RM. Effects of suppression, acceptance and spontaneous coping on pain tolerance, pain intensity and distress. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:199–209.

Purdon C. Thought suppression and psychopathology. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:1029–54.

Klasen BW, Brüggert J, Hasenbring M. Role of cognitive pain coping strategies for depression in chronic back pain. Path analysis of patients in primary care. Schmerz. 2006;20:398, 400-2, 404-6 passim. doi:10.1007/s00482-006-0470-y.

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:217–37. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

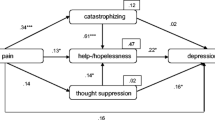

Hülsebusch J, Hasenbring MI, Rusu AC. Understanding pain and depression in back pain: the role of catastrophizing, help−/hopelessness, and thought suppression as potential mediators. IntJ Behav Med. 2015; doi:10.1007/s12529-015-9522-y.

Wegner DM, Erber R. The hyperaccessibility of suppressed thoughts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:903–12.

Wegner DM, Erber R, Zanakos S. Ironic processes in the mental control of mood and mood-related thought. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:1093–104.

Wenzlaff RM, Bates DE. Unmasking a cognitive vulnerability to depression: how lapses in mental control reveal depressive thinking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1559–71.

Schoofs D, Preuss D, Wolf OT. Psychosocial stress induces working memory impairments in an n-back paradigm. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:643–53. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.02.004.

Beevers C, Meyer B. Thought suppression and depression risk. Cognit Emot. 2004;18:850–67.

Wenzlaff RM, Luxton DD. The role of thought suppression in depressive rumination. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27:293–308. doi:10.1023/A:1023966400540.

Wegner DM, Zanakos S. Chronic thought suppression. J Pers. 1994;62:616–40.

Blumberg SJ. The white bear suppression inventory: revisiting its factor structure. Personal Individ Differ. 2000;29:943–50.

Robichaud M, Dugas MJ, Conway M. Gender differences in worry and associated cognitive-behavioral variables. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:501–16.

Rassin E. The white bear suppression inventory (WBSI) focuses on failing suppression attempts. Eur J Pers. 2003;17:285–98. doi:10.1002/per.478.

Imhof M, Schulte-Jakubowski K. The white bear in the classroom: on the use of thought suppression when stakes are high and pressure to perform increases. Soc Psychol Educ. 2015;18:431–42. doi:10.1007/s11218-015-9301-2.

Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Critical review Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–92.

Rustøen T, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Lerdal A, Paul S, Miaskowski C. Gender differences in chronic pain—findings from a population-based study of Norwegian adults. Pain Manag Nurs. 2004;5:105–17. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2004.01.004.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007:1453–7.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. 2016:NICE guideline (NG59).

Hasenbring MI, Hallner D, Klasen B, Streitlein-Bohme I, Willburger R, Rusche H. Pain-related avoidance versus endurance in primary care patients with subacute back pain: psychological characteristics and outcome at a 6-month follow-up. Pain. 2012;153:211–7.

Beck AT. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Kammer D. Eine Untersuchung der psychometrischen Eigenschaften des deutschen Beck-Depressionsinventars (BDI). Diagnostica. 1983;29:48–60.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5.

Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:163–70.

Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002;27:20.

Hasenbring M, Marienfeld G, Ahrens S, Soyka D. Chronic pain factor in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Schmerz. 1990;4:138–50. doi:10.1007/BF02527877.

Hasenbring M, Hallner D, Rusu AC. Endurance-related pain responses in the development of chronic back pain. In: Hasenbring M, Rusu AC, Turk DC, editors. From acute to chronic back pain: risk factors, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 295–314.

Hasenbring M, Kurtz B, Marienfeld G. Erfahrungen mit dem Kieler Interview zur subjektiven Situation (KISS). In: Brähler E, Dahme B, Klapp BF, Davies-Osterkamp S, Jacobi P, Koch-Gromus U, et al., editors. Psychosoziale Onkologie. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1989. p. 68–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74986-5_6.

Hasenbring M, Klasen B, Schaub C, Hallner D. KISS-BR. Kieler Interview zur subjektiven Situation – Belastungen/Ressourcen. In: Schumacher J, Klaiberg A, Brähler E, editors. Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2003. p. 189–91.

Sudhaus S, Fricke B, Schneider S, Stachon A, Klein H, von Düring M, Hasenbring M. The cortisol awakening response in patients with acute and chronic low back pain. Relations with psychological risk factors of pain chronicity. Schmerz. 2007;21:202–204, 206-11. doi:10.1007/s00482-006-0521-4.

Schulz-Kindermann F, Hennings U, Ramm G, Zander AR, Hasenbring M. The role of biomedical and psychosocial factors for the prediction of pain and distress in patients undergoing high-dose therapy and BMT/PBSCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:341–51. doi:10.1038/sj.bmt.1703385.

Shultz S, Averell K, Eickelman A, Sanker H, Donaldson MB. Diagnostic accuracy of self-report and subjective history in the diagnosis of low back pain with non-specific lower extremity symptoms: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:18–27.

Grebner M, Breme K, Rothoerl R, Woertgen C, Hartmann A, Thomé C. Coping und Genesungsverlauf nach lumbaler Bandscheibenoperation. Schmerz. 1999;13:19–30. doi:10.1007/s004829900011.

Hallner D, Hasenbring M. Classification of psychosocial risk factors (yellow flags) for the development of chronic low back and leg pain using artificial neural network. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:151–4. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.107.

Rommel O, Kley RA, Dekomien G, Epplen JT, Vorgerd M, Hasenbring M. Muscle pain in myophosphorylase deficiency (McArdle’s disease): the role of gender, genotype, and pain-related coping. Pain. 2006;124:295–304. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.017.

Scholich SL, Hallner D, Wittenberg RH, Rusu AC, Hasenbring MI. Pilot study on pain response patterns in chronic low back pain. The influence of pain response patterns on quality of life, pain intensity and disability. Schmerz. 2011;25:184–90. doi:10.1007/s00482-011-1023-6.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1988.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Boston, Mass. [u.a.]: Allyn and Bacon; 2001.

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. SAGE: Los Angeles; 2015.

Schmider E, Ziegler M, Danay E, Beyer L, Bühner M. Is it really robust? Methodology. 2010;6:147–51. doi:10.1027/1614-2241/a000016.

IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows: version 23.0. Armonk: IBM Corporation; 2015.

Szasz PL. Thought suppression, depressive rumination and depression: a mediation analysis. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies. 2009;9:199–209.

Garland EL, Brown SM, Howard MO. Thought suppression as a mediator of the association between depressed mood and prescription opioid craving among chronic pain patients. J Behav Med. 2016;39:128–38. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9675-9.

Gijsbers van Wijk CM, Huisman H, Kolk AM. Gender differences in physical symptoms and illness behavior. A health diary study. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:1061–74.

Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

McGonagle KA, Kessler RC. Chronic stress, acute stress, and depressive symptoms. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18:681–706.

Hammen C, Davila J, Brown G, Ellicott A, Gitlin M. Psychiatric history and stress: predictors of severity of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:45–52.

Bouteyre E, Maurel M, Bernaud JL. Daily hassles and depressive symptoms among first year psychology students in France: the role of coping and social support. Stress Health. 2007;23:93–9.

Wolf TM, Elston RC, Kissling GE. Relationship of hassles, uplifts, and life events to psychological well-being of freshman medical students. Behav Med. 1989;15:37–45. doi:10.1080/08964289.1989.9935150.

Burks N, Martin B, Martin MA. Every day’s problems and life change events: ongoing versus acute sources of stress. J Hum Stress. 1985;11:27–35.

Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personal Individ Differ. 2004;37:1401–15. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010.

Lebe M, Hasenbring MI, Schmieder K, Jetschke K, Harders A, Epplen JT, et al. Association of serotonin-1A and -2A receptor promoter polymorphisms with depressive symptoms, functional recovery, and pain in patients 6 months after lumbar disc surgery. Pain. 2013;154:377–84. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.11.017.

Beevers CG, Wenzlaff RM, Hayes AM, Scott WD. Depression and the ironic effects of thought suppression: therapeutic strategies for improving mental control. Clinical Psycholgy: Science and Practice. 1999;6:133–48.

Linton SJ, Bergbom S. Understanding the link between depression and pain. Scand J Pain. 2011;2:47–54. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2011.01.005.

Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Sex differences in pain perception. Gend Med. 2005;2:137–45.

Munce SEP, Stewart DE. Gender differences in depression and chronic pain conditions in a national epidemiologic survey. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:394–9. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.394.

Pincus T, Vogel S, Burton AK, Santos R, Field AP. Fear avoidance and prognosis in back pain: a systematic review and synthesis of current evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3999–4010. doi:10.1002/art.22273.

Sieben JM, Vlaeyen JWS, Portegijs PJM, Verbunt JA, van Riet-Rutgers S, Kester ADM, et al. A longitudinal study on the predictive validity of the fear-avoidance model in low back pain. Pain. 2005;117:162–70. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.002.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: HA 1684) awarded to MIH. We further thank Nina Kreddig for providing helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: HA 1684) awarded to MIH.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

This article was updated to correct the author names.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9709-5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konietzny, K., Chehadi, O., Streitlein-Böhme, I. et al. Mild Depression in Low Back Pain: the Interaction of Thought Suppression and Stress Plays a Role, Especially in Female Patients. Int.J. Behav. Med. 25, 207–214 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9657-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9657-0