Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of the current study were to (1) describe the restructuring and dissemination of a Canada-wide intervention curriculum designed to enhance health care professionals’ prescription of physical activity to patients with physical disabilities, and (2) examine interventionists’ social cognitions for, and their acceptance and adoption of, the new curriculum.

Methods

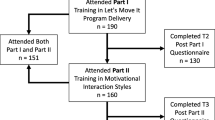

A participatory curriculum development process was utilized, resulting in a theory- and evidence-based curriculum. Interventionists (N = 28) were trained in curriculum delivery and most (n = 22) completed measures of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs assessing their cognitions for delivering the new curriculum at pre- and post-training and at 6-month follow-up. Interventionists also completed a Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) measure assessing their opinion of whether the new curriculum met characteristics that would facilitate its adoption and use.

Results

Interventionists reported strong TPB cognitions for curriculum use before training. Significant increases emerged for some TPB constructs (ps ≤ 0.025) from pre- to post-training, and significant decreases were seen in some TPB constructs (ps ≤ 0.024) between post-training and 6-month follow-up. The interventionists rated the new curriculum as high on all the DOI characteristics.

Conclusion

The theory-driven, participatory development process facilitated interventionists’ social cognitions towards and adoption of the new curriculum. Positive increases in TPB cognitions from pre- to post-training were not maintained at follow-up. Further research is needed to determine if these changes in cognitions are indicative of a curriculum “reinvention” process that facilitates long-term curriculum use. Understanding curriculum adoption and implementation is a crucial step to determining the potential population impact of the intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the purposes of this paper, the term HCPs includes physicians, nurses, rehabilitation therapists, kinesiologists, and any other professional who provides LTPA advice to patients.

The CPC is a non-profit, private organization dedicated to the development and promotion of a sustainable Paralympic sport system in Canada. The CPC aims to promote the success of athletes with a physical disability at all levels of parasport (i.e., parallel sport opportunities for people with a physical disability).

An overview of the content of the new 30-slide curriculum can be found in Cripps, Tomasone, and Staples [14].

As an index of internal consistency of the measures, Cronbach’s alpha (α) values were calculated when the scales had three or more items, and Pearson correlations (r) were calculated when the scales had only two items. Internal consistency is considered adequate if α ≥ 0.7 [28].

References

Statistics Canada. Participation and Activity Limitation Survey 2006 Tables (Cat. No. 89-628-XIE - No. 003). 2007; http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=40. Accessed 10 Feb 2011.

Statistics Canada. Participation and Activity Limitation Survey 2001. Ottawa, Ontario 2001.

Cooper RA, Quatrano LA, Axelson PW, et al. Research on physical activity and health among people with disabilities: a consensus statement. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1999;36:142–59.

Durstine JL, Painter P, Franklin BA, Morgan D, Pitetti KH, Roberts SO. Physical activity for the chronically ill and disabled. Sports Med. 2000;30(3):207–19.

Giacobbi PR, Stancil M, Hardin B, Bryant L. Physical activity and quality of life experienced by highly active individuals with physical disabilities. Adap Phys Act Q. 2008;25:189–207.

Heath GW, Fentem PH. Physical activity among persons with disabilities: a public health perspective. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1997;25:195–233.

Tomasone JR, Wesch N, Martin Ginis KA, Noreau L. Spinal cord injury, physical activity, and quality of life: a systematic review. Kinesiol Rev. 2013;2:113–29.

Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Chapter 7: Additional considerations for some adults. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter7.aspx. Accessed 14 November 2012.

Martin Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, et al. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1088–96.

Faulkner G, Gorczynski P, Arbour KP, Letts L, Wolfe DL, Martin Ginis KA. Messengers and methods of disseminating health information among individuals with spinal cord injury. In: Berkovsky TC, editor. Handbook of spinal cord injuries. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2010. p. 329–74.

Glasgow RE, Eakin EG, Fisher EB, Bacak SJ, Brownson RC. Physician advice and support for physical activity: results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:189–96.

Andersen R, Blair S, Cheskin L, Barlett S. Encouraging patients to become more physically active: the physician’s role. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:395–400.

Douglas F, Torrance N, van Teijlingen E, Meloni S, Kerr A. Primary care staff’s views and experiences related to routinely advising patients about physical activity: a questionnaire survey. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:138.

Cripps DG, Tomasone JR, Staples KL. Canadian initiatives in disability sport and recreation: an overview of the moving to inclusion and changing minds, changing lives programs. In: Brittain I, editor. Disability sport: a vehicle for social change? Champaign: Common Ground Publishing; 2013. p. 22–8.

Martin Ginis KA, Latimer-Cheung AE, Corkum S, et al. A case study of a community-university multidisciplinary partnership approach to increasing physical activity participation among people with spinal cord injury. Transl Behav Med. 2013;2:516–22.

Developing and evaluaing complex interventions: New guidance. Medical Research Council; 2008. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance. Accessed 10 Feb 2011.

Estabrooks PA, Bradshaw M, Dzewaltowski DA, Smith-Ray RL. Determining the impact of Walk Kansas: applying a team-building approach to community physical activity promotion. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:1–12.

Kleges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:66–75.

Wandersman A, Florin P. Community interventions and effective prevention. Am Psychol. 2003;58:441–8.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnson M, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:107–12.

Godin G, Belanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviors: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;3:36.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. 2002. http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2011.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Differentiating motivation and control in the theory of planned behavior. Psychol Health Med. 2004;9:205–15.

Keppel G. Design and analysis: a researcher’s handbook. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1993.

Tomasone JR, Martin Ginis KA, Estabrooks PA, Domenicucci L. “Changing Minds”: determining the effectiveness and key ingredients of an educational intervention to enhance health care professionals’ intentions to prescribe physical activity to patients with physical disabilities. Implement Sci. 2014;9:30.

Kline P. The handbook of psychological testing. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1999.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge The Canadian Paralympic Committee for their assistance with the dissemination of the new curriculum and data collection from the interventionists, as well as Krystn Orr for her assistance with data collection. This study was partially supported by an Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Mentor-Trainee Capacity Building Award awarded to the first and the second authors (JRT and KAMG), and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Community-University Research Alliance grant awarded to the second author (KAMG).

Conflict of Interest

JRT and KAMG sat on the CMCL Advisory Committee when the intervention curriculum was being restructured. LD was the Manager of Sport Development at the Canadian Paralympic Committee during the study period. PAE has no conflicts of interest to report.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomasone, J.R., Martin Ginis, K.A., Estabrooks, P.A. et al. Changing Minds, Changing Lives from the Top Down: An Investigation of the Dissemination and Adoption of a Canada-Wide Educational Intervention to Enhance Health Care Professionals’ Intentions to Prescribe Physical Activity. Int.J. Behav. Med. 22, 336–344 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-014-9414-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-014-9414-6