Abstract

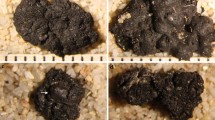

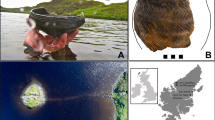

Archaeobotanical remains of ground cereals from prehistoric northern Greece are discussed in this paper within the context of ethnographic and textual evidence for similar food preparations encountered in countries of the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The archaeobotanical remains consist of ground einkorn and barley grain, stored in this form, from the sites of Mesimeriani Toumba and Archondiko respectively, located in the region of central Macedonia, northern Greece. The results of published pilot studies involving macroscopic, experimental, and scanning electron microscopic examination of these archaeological finds seem to suggest that these products correspond to preprocessed cereals, stored in this form. It is also likely that some at least of these finds were produced from boiled and subsequently ground cereal grains. This practice identified in the prehistoric material is similar to various forms of processing cereals still widely encountered in rural areas of modern Greece and other circum-Mediterranean countries. These products are known in Greece under the names of pligouri (bulgur) and trachanas. Through a combined examination of archaeobotanical, ethnographic, and textual evidence it is argued that the idea of pre-processing cereals for piecemeal consumption throughout the year is of considerable antiquity in this part of the world. Drawing information from food science research on similar, modern traditional preparations of the same geographical region, the paper highlights the advantages of pre-processing cereals for later consumption, which offers insights into likely prehistoric subsistence practices. Parboiling cereal grains or mixing grains with milk products in the summer would have made excellent use of seasonally available ingredients by converting them into nutritious and storable foodstuffs, which could then be consumed as part of daily meals with very little additional cooking effort and fuel. This ease of conversion into a filling meal may justify us considering them as ‘traditional fast foods’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The material is currently under study by the author with financial support by INST.A.P.

Throughout the paper, I will use the word trachanas encompassing the other names encountered in different parts of Greece.

The word trachanas in Greece and tarhana in Turkey also correspond to a totally different type of preparation, whereby wheat flour and yoghourt are mixed together with other ingredients (eggs, various vegetables and/or spices) and left to ferment overnight (Fig. 9b, top row). This preparation is not dealt with here.

Γεωπονικά, Edited by Beckh, published in 1895 Leipzig by Τeubner.

Χόνδρου ποίησις.

3.7.1 Ζειὰς πτιστέον καὶ βραστέον καὶ ἐμβλητέον εἰς ζεστὸν ὕδωρ, καὶ συνεκπιαστέον. ἔπειτα γύψον λευκὴν κοπτέον καὶ εἰς λεπτὸν σηστέον, ἄμμου τε τῆς λευκοτάτης καὶ λεπτοτάτης τὸ τέταρτον σὺν γύψου μέρει κατ᾽ ὀλίγον μικτέον ἐπιπτισσομένῃ τῇ ζειᾷ αὖθις. σκευαζέσθω δὲ ἐν ταῖς ὑπὸ κύνα ἡμέραις, ἵνα μὴ ὀξίσῃ. ἐπὰν δ᾽ ἅπασα ἐπιπτισθῇ, κοσκίνῳ κοσκινευέσθω ἁδροτέρῳ.

3.7.2 κάλλιστος ὁ πρῶτος σησθεὶς γίνεται χόνδρος· δεύτερος ὁ ἐπὶ τούτῳ· καὶ ἐλάττων ὁ τρίτος.

English translation after Dalby (2011):

7. Making chondros.

Pound emmer spikelets, crack them, put in boiling water, squeeze them out. Then pound white gypsum and sift it fine; a quarter part of the whitest and finest sand, with each part of gypsum, to be gradually mixed with the emmer as it is being husked. This is made in the dog days, so that it will not go sour. When it is all husked, pass it though a rather coarse sieve.The best is the first-sieved chondros; the second is next best; the third is poorer.

Γεωπονικά, Edited by Beckh, published in 1895 in Leipzig by Τeubner.

Τράγου ποίησις.

3.8 Τὸν Ἀλεξανδρῖνον σῖτον λεγόμενον βρεκτέον καὶ πτιστέον καὶ ξηραντέον ἐν ἡλίῳ θερμῷ· εἶτ᾽ αὖθις τὰ αὐτὰ ποιητέον, ἄχρις οὗ οἵ τε ὑμένες τοῦ σίτου καὶ τὸ ἰνῶδες ὰποπέσῃ. Οὕτω τε ξηραντέον καὶ ὰποθετέον τὸν τράγον ἐκ τῆς εὐγενοῦς ὀλύρας.

English translation after Dalby 2011:

8. Making tragos.

Soak and pound Alexandrinos wheat and dry it in hot sun. Then repeat the process until the glumes and fibrous parts of the wheat are all removed.

Tragos from good-quality emmer can be dried and stored in the same way.

References

Abdalla, M (1989) Bulgur—an important wheat product in the cuisine of contemporary Assyrians in the Middle East. In: H Walker H (Ed.) Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1989: Staple Foods. London: Prospect Books, 1990, p. 27–37

Alais C, Linden G (1991) Food biochemistry. Masson: Paris.

Amouretti M-C (1986) Le Pain et l’Olivier dans la Grèce Antique (Centre de Recherche d’Histoire Ancienne 67. Annales Littéraires de l’Université de Besançon). Les Belles-lettres, Paris

Anyfantakis E, Georgala A, Vamvakaki A, Moschopoulou A, Miari Ch (2004) Ξινόχοντρος, ένα παραδοσιακό βιολογικό προϊόν της Κρήτης (Xinochondros, a traditional, organic product of Crete). Eptalofos, Athens

Aubaile-Sallenave F (1994) Al-Kishk: the past and present of a complex culinary practice. In: S Zubaida and R Tapper (eds.). A taste of thyme: culinary cultures of the Middle East, London, I.B. Tauris (2006 reprint), 104–139.

Baik B-K, Ullrich SE (2008) Barley for food: characteristics, improvement, and renewed interest. J Cereal Sci 48:233–242

Bayram M (2000) Bulgur around the world. Cereal Food World 45:80–82

Bayram M (2006) Determination of the cooking degree for bulgur production using amylose/iodine, centre cutting and light scattering methods. Food Control 17(5):331–335

Bera S (2004) Food and nutrition of the Tibetan women in India. Anthropologist 6(3):175–180

Bilgiçli N, Elgün A, Türker S (2006) Effects of various phytase sources on phytic acid content, mineral extractability and protein digestibility of tarhana. Food Chem 98(2):329–337

Blandino A, Al-Aseeri ME, Pandiella SS, Cantero D, Webb C (2003) Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res Int 36(6):527–543

Boardman S, Jones G (1990) Experiments on the effects of charring cereal plant components. J Archaeol Sci 17:1–11

Borghi B, Castagna R, Corbellini M, Heun M, Salamini F (1996) Breadmaking quality of einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum ssp. monococcum). Cereal Chem 73(2):208–214

Bozi S (1997) Kappadokia, Ionia, Pontos: tastes and traditions (Καππαδοκία, Ιονία, Πόντος: Γεύσεις και Παραδόσεις). Asterismos-Evert, Athens

Brandolini A, Marturini M, Plizzari L, Hidalgo JC (2008) Chemical and technological properties of Triticum monococcum, Triticum turgidum and Triticum aestivum. Technica Molitoria International 59(5/A):85–93

Braun T (1995) Barley cakes and emmer bread. In: Wilkins J, Harvey D, Dobson M (eds) Food in antiquity. University of Exeter Press, Exeter, pp 25–37

D’ Andrea CA, Mitiku-Haile (2002) Traditional emmer processing in highland Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol 22:179–217

Dagher SM (1991) Traditional Foods in the Near East. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 50. FAO: Rome

Dalby A (2011) Geoponica: farm work or agricultural pursuits. Prospect Books, London

Delatola-Foskolou N (2006) Κυκλάδων Γεύσεις (Tastes of the Cyclades), Tenos, Mare.

Economidou PL (1975) Studies on Greek trahanas—a wheat fermented milk food. MSc Thesis, Cornell University.

Erkan H, Çelik S, Bilgi B, Köksel H (2006) A new approach for the utilization of barley in food products: barley tarhana. Food Chem 97(1):12–18

Ertuğ F (2004) Recipes of old tastes with einkorn and emmer wheat. TÜBA-AR 7:177–188

Evangelatou F (1996) Ξεχασμένες Νοστιμιές του Κυπριακού Χωριού (Forgotten tastes of the Cypriot Village) A. Filis, Lemesos.

Evans JD (1964) Excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Knossos 1957–60. Part 1. Annu Br Sch Athens 59:132–240

Evershed R (2008) Experimental approaches to the interpretation of absorbed organic residues in archeological cereamics. World Archaeol 40:26–47

Evershed RP, Payne S, Sherratt AG, Copley MS, Coolidge J, Urem-Kotsu D, Kotsakis K, Özdoğan M, Özdoğan AE, Nieuwenhuyse O, Akkermans PMMG, Bailey D, Andeescu R-R, Campbell S, Farid S, Hodder I, Yalman N, Özbaşaran M, Bıçakcı E, Garfinkel Y, Levy T, Burton MM (2008) Earliest date for milk use in the Near East and southeastern Europe linked to cattle herding. Nature 455(7212):528–531

Gennadios P (1914) Λεξικόν Φυτολογικόν (Lexikon Phytologikon). Αθήνα, Εκδόσεις Τροχαλία (reprint 1997).

Giuliani A, Karagoz A, Zencirci N (2007) Marketing underutilized species: livelihoods and markets of emmer (Triticum dicoccon) in Turkey. In Global Facilitation Unit for underutilised plant species (GFU). Available from: http:/www.underutilized-species.org/record_details.asp?id=1052

Grammenos D, Kotsos S (2002) Ανασκαφή στην Προϊστορική Θέση ‘Μεσημεριανή Τούμπα’ Τριλόφου Θεσσαλονίκης (Excavations at the Prehistoric site “Mesimeriani Toumba” Trilofou Thessalonikis). Archaeοlogical Institute, Thessaloniki

Halstead P (1981) Counting sheep in Neolithic and Bronze Age Greece. In: Hodder I, Isaac G, Hammond N (eds) Pattern of the past. Studies in honour of David Clarke. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 307–339

Halstead P (1999) Neighbours from hell? The household in Neolithic Greece, στον τόμο P. Hastead (επιμ.) Neolithic Society in Greece. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, pp 77–95

Halstead P, Jones G (1989) Agrarian ecology in the Greek Islands: time stress, scale and risk. J Hell Stud 109:41–55

Hamilakis Y (2008) Time, performance and the production of a mnemonic record: from feasting to an archaeology of eating and drinking. In: R. Laffineur, M.-L. Hitchcock and J. Crowley (Eds) The Aegean Feast, Aegeum 29, p. 3–19.

Hansen JM (1988) Agriculture in the prehistoric Aegean: data versus speculation. AJA 92:39–52

Hansen J (1991) The palaeoethnobotany of Franchthi Cave. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Hansen J (1992) Franchthi cave and the beginnings of agriculture in Greece and the Aegean, in P. Anderson-Gerfaud (ed.) Prehistoire de l’Agriculture: Nouvelles Approches Experimentales et Ethnographiques (Monographie du CRA n.6): 231–247. Paris: Editions CNRS.

Hansen J (2000) palaeoethnobotany and palaeodiet in the Aegean region: notes on legume toxicity and related pathologies. In: Vaughn SJ, Coulson WDE (eds) Palaeodiet in the Aegean. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 13–27

Hayden B (2003) Were luxury foods the first domesticates? Ethnoarchaeological perspectives from Southeast Asia. World Archaeol 34(3):458–469

Hidalgo A, Brandolini A, Gazza L (2008) Influence of steaming treatment on chemical and technological characteristics of einkorn (Triticum monococcum L. subsp. monococcum) whole meal flour. Food Chem 111:549–555

Hill S, Bryer A (1995) Byzantine Porridge: Tracta, Trachanas, and Trahana, in Food in Antiquity, eds. John Wilkins, David Harvey, Mike Dobson, F. D. Harvey. Exeter University Press

Hillman G (1981) Reconstructing crop husbandry practices from charred remains of crops. In: Mercer R (ed) Farming practice in British prehistory. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, pp 123–162

Hillman G (1984) Traditional husbandry and processing of archaic cereals in recent times. The operations, products, and equipment which might feature in Sumerian texts, part I: the glume wheats. Bull Sumer Agric 1:114–152

Jones G (1987) A statistical approach to the archaeological identification of crop processing. J Archaeol Sci 14:311–323

Jones G (1998) Distinguishing food from fodder in the archaeobotanical record. Environ Archaeol 1(1998):95–98

Jones G, Halstead P, Wardle K, Wardle D (1986) Crop storage at Assiros. Sci Am 254:96–103

Jones G, Valamoti SM, Charles M (2000) Early crop diversity: a ‘new’ glume wheat from northern Greece. Veg Hist Archaeobot 9:133–146

Karabela M (2002) Γεύσεις της Λακωνικής Γης (Tastes of the Land of Lakonia). Patakis, Athens.

Katz SH (1990) An evolutionary theory of cuisine. Human Nature 1:233–259

Kiziridou Th. (2002) Ποντίων Εδέσματα (Foods of the Pontic People). Kyriakidis, Thessaloniki.

Kochilas D (2001) The glorious foods of Greece: traditional recipes from the islands, cities, and villages. William Morrow Cookbooks, New York, USA

Kohler-Schneider M, Caneppele A (2009) Late Neolithic agriculture in eastern Austria: archaeobotanical results from sites of the Baden and Jevišovice cultures (3600–2800 B.C.). Veg Hist Archaeobot 18:61–74

Köksel H, Edney MJ, Özkaya B (1999) Barley Bulgur: effect of processing and cooking on chemical composition. J Cereal Sci 29(2):185–190

Kotsachristou D (2008) Archaeobotanical investigations in prehistoric Macedonia: plant remains from Toumba Thessalonikis.

Kotsakis K (2010) H κεραμική της Νεότερης Νεολιθικής στη βόρεια Ελλάδα (Late Neolithic pottery in northern Greece). In N. Papadimitriou and Z. Tsirsoni (eds.) Η Ελλάδα στο ευρύτερο πολιτισμικό πλαίσιο των Βαλκανίων κατά την 5η και 4η χιλιετία π.Χ. (Greece in the wider cultural context of the Balkans during the fifth and fourth millennium B.C.), 66–75. Athens, N.P.Goulandris Foundation.

Koukoules F (1952) Βυζαντινών βίος και Πολιτισμός (Life and culture of the Byzantine people). Papazisis publications, Athens

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki Ch, Todorova H, Aslanis I, Vajsov I, Valla M (2007) Promachon-topolnitsa: a Greek–Bulgarian archaeological project. In: Todorova H, Stevanovich M, Ivanov G (eds) The Struma/Strymon river valley in prehistory. Gerda Henkel Stiftung, Sofia, pp 43–78, In the Steps of Harvey Gaul, vol. 2

Kreuz A (2007) Archaeobotanical perspectives on the beginning of agriculture north of the Alps. In: Colledge S, Conolly J (eds) The Origin and Spread of Domestic Plants in SW Asia and Europe. Institute of Archaeology, London, pp 259–294

Kroll H (1983) Kastanas. Ausgrabungen in einem Siedlungshügel der Bronze- und Eisenzeit Makedoniens, 1975–1979: Die Pflanzenfunde. Prähistorische Archäologie in Südosteuropa 2. Volker Spiess, Berlin

Kroll H (2003) Rural plenty: the result of hard work. Rich middle Bronze Age plant remains from Agios Mamas, Chalkidike, In: Wagner GA, Pernicka E, Uerpmann H-P (eds) Troia and the Troad. Scientific approaches. Heidelberg-New York, Berlin, pp 293–302, 403–432

Kroll HJ (1991) Südosteuropa. In: van Zeist W, Wasylikowa K, Behre K-E (eds) Progress in old world palaeoethnobotan. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 161–177

Marinova E (2006) Vergleichende paläoethnobotanische Untersuchung zur Vegetationsgeschichte und zur Entwicklung der prähistorischen Landnutzung in Bulgarien, Berlin-Stuttgart, J. Cramer in der Gebrüder Borntraeger, 2006 (Dissertationes Botanicae 401).

Martin M (1980) Milk and firewood in the ecology of Turan. Expedition 22(4):1–3

Megaloudi F (2006) Plants and diet in Greece from Neolithic to classic periods: the archaeobotanical remains. Archaeopress, Oxford, British Archaeological Reports International Series 1516

Mensah P, Drasar BS, Harrison TJ, Tomkins AM (1991) Fermented cereal gruels: towards a solution of the weanling's dilemma. Food and Nutr Bull 13(1):50–57

Micha-Lampaki A (1984) Η Διατροφή των Αρχαίων Ελλήνων κατά τους Αρχαίους Κωμωδιογράφους (Food of the Ancient Greeks according to Ancient Comedy Poets). Athens, PhD Dissertation.

Milke H, Rodemann B (2007) Der Dinkel, eine besondere Weizenart-Anbau, Pflanzenschutz. Ernte und Verarbeitung. Nachrichtenbl. Deut Pflanzenschutzd 59:40–45

Morcos SR, Morcos WR (1977) Diets in ancient Egypt. Prog Food Nutr Sci 2(10):457–471

Morcos SR, Hegazi SM, El-Damhougy ST (1973) Fermented foods in common use in Egypt I. The nutritive value of kishk. J Sci Food Agric 24(10):1153–1156

Muir DD, Tamime AY, Khaskheli M (2000) Effect of processing conditions and raw materials on the properties of Kishk 2. Sensory profile and microstructure. Lebensm Wiss Technol 33(6):452–461

Mylonas GE (1929) Excavations at Olynthus, I: the Neolithic settlement. John Hopkins Press, Baltimore

Nesbitt M, Samuel D (1996) From staple crop to extinction? The archaeology and history of the Hulled Wheats, in S. Padulosi, K. Hammer and J. Heller (eds.) Hulled wheats. Promoting the Conservation and Use of Underutilised and Neglected Crops, 4: 41–100. Rome: International Plant Genetic Resources Institute.

Palmer C (2002) Milk and cereals: identifying food and food identity among Fallāhīn and Bedouin in Jordan. Levant 34:173–195

Papaefthymiou A, Pilali A, Papadopoulou E (2007) Les installations culinaires dans un village du Bronze Ancien en Grèce du Nord: Archondiko Giannitsa, in, C. Mee and J. Renard (eds.) Cooking up the past, Oxford, Oxbow, 2007, p. 136–147.

Papaefthymiou-Papanthimou A, Pilali-Papasteriou A, Basogianni D, Papadopoulou E, Tsagaraki E, Fappas I (2002) Αρχοντικό 2000. Τυπολογική παρουσίαση και ερμηνευτικά προβλήματα των πηλόκτιστων κατασκευών (Archondiko 2000. Typological presentation and interpretive problems concerning the clay structures). AEMTH 14:421–433

Pappa M, Halstead P, Kotsakis K, Urem-Kotsou D (2004) Evidence for large-scale feasting at Late Neolithic Makriyalos, N Greece, in P. Halstead and J. Barrett (Ed.) Food, cuisine and society in prehistoric Greece, Oxford, Oxbow, 2004, p. 16–44 (Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology 5)

Pavlov I (2001) Prisastvia na hraneneto po balgarskite zemi prez XV-XIX vek (Η παρουσία της διατροφής στα Βουλγαρικά εδάφη μεταξύ του XV και του XIX αιώνα). BAN, Sofia

Peña-Chocarro L (1999) Prehistoric agriculture in Spain. The application of ethnographic models. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, British Archaeological Reports International Series 818

Peña-Chocarro L, Zapata Peña L (2003) Post-harvesting processing of hulled wheats. An ethnoarchaeological approach. In: Anderson PC, Scott Cummings L, Schippers TK, Simonel B (eds) Le traitement des rrécoltes: Un regard sur la diversité, du Néolithique au présent. Actes des XXIIIe rencontres internationales d’archéologie et d’histoire d’Antibes. Éditions APDCA, Antibes, pp 99–113

Peña-Chocarro, Leonor, Lydia Zapata Peña, Jesús Emilio González Urquijo and Juan José Ibáñez Estévez (2009). ‘Einkorn (Triticum monococcum L.) cultivation in mountain communities of the western Rif (Morocco): An ethnoarchaeological project’. In Fairbairn, A. and E. Weiss (eds). Ethnobotanist of distant pasts: Archaeological and ethnobotanical studies in honour of Gordon Hillman. Oxford: Oxbow.

Pence JW, Ferrel RE, Robertson JA (1964) Effects of processing on B vitamins and mineral contents of bulgur. Food Technol 18:171

Perlès C (1977) Prehistoire du Feu. Paris.

Perlès C (1999) Feeding strategies in prehistoric times. In: Flandrin JL, Montanari M (eds) Food: a culinary history from antiquity to the present. Columbia University Press, New York

Perlès C (2001) The early Neolithic of Greece. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Perlès C, Vitelli KD (1999) Craft specialisation in the Neolithic of Greece. In: Hastead P (ed) Neolithic Society in Greece. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, pp 96–107

Perry C (1983) Tracta, trahanas, kishk. Petits Propos Culinaires 14:58–59

Pieroni A, Torry B (2007) Does the taste matter? Taste and medicinal perceptions associated with five selected herbal drugs among three ethnic groups in West Yorkshire, Northern England. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 3:21

Prevost-Dermarkar S (2002) Les foyers et les fours domestiques en Egee au Neolithique et a l’Age du Bronze. Civilisations 49:223–237

Procopiou H (2003) Les techniques de décorticage dans le monde égéen: étude ethno- archéologique dans les Cyclades, in Anderson, P-C., Cummings, L.-C., Schippers, T.K., Simonel, B. (eds.), Le traitement des récoltes: un regard sur la diversité, du Néolithique au Présent, XXIIIe Rencontres Internationales d’Archéologie et d’Histoire d’Antibes, Antibes, p.115–136

Psilakis N, Psilaki M (2001) Το Ψωμί των Ελλήνων (The bread of the Greeks). Karmanor Publications, Herakleion

Psilakis N, Psilakis M (2001) Το Ψωμί των Ελλήνων (The bread of the Greeks). Karmanor Publications, Heracleon

Renfrew JM (2003) Grains, seeds and fruits from prehistoric Sitagroi. In: Elster ES, Renfrew C (eds) Prehistoric Sitagroi: Excavations in Northeast Greece, 1968-1970, vol.2: The Final Report. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Los Angeles, pp 1–28

Rivera-Nuñez D, Obon de Castro C (1989) La dieta cereal prehistorica y su supevivencia en el area Mediterranea. Trab Prehist 46:247–254

Runnels C (1988) Early bronze age stone mortars from the Southern Argolid. Hesperia 57:257–272

Samuel D (2000) Brewing and baking. In: Nicholson PT, Shaw I (eds) Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 537–576

Sarpaki A (2001) Processed cereals and pulses from the Late Bronze Age site of Akrotiri, Thera; preparations prior to consumption: a preliminary approach to their study. Annu Br Sch Archaeol Athens 96:27–40

Sengun IY, Nielsen DS, Karapinar M, Jakobsen M (2009) Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Tarhana, a traditional Turkish fermented food. Int J Food Microbiol 135(2):105–111

Shea J (2007) What stone tools can (and Can’t) tell us about early hominin diets. In: Ungar P (ed) Evolution of the human diet: the known, the unknown and the unknowable. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 213–229

Simango C (1997) Potential use of traditional fermented foods for weaning in Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med 44(7):1065–1068

Singh B, Dodda LM (1979) Studies on the preparation and nutrient composition of bulgur from Triticale. J Food Sci 44(2):449–452

Sophronidou M, Tsirtsoni Z (2007) What are the legs for? Vessels with legs in the Neolithic and early Bronze Age Aegean. In: Mee C, Renard J (eds) Cooking up the Past. Oxbow, Oxford, pp 123–135

Stahl AB (1984) Hominid dietary selection before fire. Curr Anthropol 25(2):151–168

Stahl B (1989) Plant food processing: the implications for food quality. In: Harris DR, Hillman GC (eds) Foraging and farming: the evolution of plant exploitation. Unwin Hyman, London, pp 171–194

Steinkraus KH (1983) Lactic acid fermentation in the production of foods from vegetables, cereals and legumes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 49(3):337–348

Steinkraus K (1996) Handbook of indigenous fermented foods. M. Decker, New York

Stika HP (1995) Traces of a possible Celtic brewery in Eberdingen-Hochdorf, Kreis Ludwigsburg, southwest Germany. Veg Hist Archaeobot 5(1–2):81–88

Stroulia A (2011) Passive abrasive tools and grain preparation for consumption at Franchthi Cave, in Alessandra Kolosimo (Ed.) Macine nell’antichità: dalla preistoria all’età romana—L’area egea, Ufficio Beni Archeologici Bolzano, Italy (in press).

Tamime Y, O’Connor TP (1995) Kishk—a dried fermented milk/cereal mixture. Int Dairy J 5:109–128

Tamime AY, Muir DD, Khaskheli M, Barclay MNI (2000) Effect of processing conditions and raw materials on the properties of Kishk 1. Compositional and Microbiological Qualities

Toufeili I, Melki C, Shadarevian S, Robinson RK (1998) Some nutritional and sensory properties of bulgur and whole wheatmeal kishk (a fermented milk–wheat mixture). Food Qual Prefer 10(1):9–15

Tsikritzi-Momtsiou M, Ftaka-Tsikritzi F (2006) Γεύσεις από Παλιά Κοζάνη, (Tastes from Old Kozani) Volume 2. Koventarios Library and Book Institute of Kozani, Kozani

Tsoraki C (2007) Unravelling ground stone life histories the spatial organization of stone tools and human activities at LN Makriyalos, Greece. Documenta Prehistorica 34

Valamoti SM (2001) Archaeobotanical Investigations of Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Agriculture and Plant Exploitation in northern Greece. PhD thesis: Sheffield University.

Valamoti SM (2002) Food remains from bronze age Archondiko and Mesimeriani Toumba in northern Greece? Veg Hist Archaeobot 11:17–22

Valamoti SM (2003) Neolithic and early Bronze Age ‘food’ from northern Greece: the archaeobotanical evidence, in M. Parker-Pearson (Ed.) Food, Culture and Identity in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, Oxford, British Arcaheological Reports, 2003, p. 97–112 (British Arcaheological Reports 1117).

Valamoti S (2004) Plants and people in late Neolithic and early bronze age Northern Greece. An archaeobotanical investigation, Oxford, Archaeopress (British Archaeological Reports International Series 1258).

Valamoti SM (2007) Food across borders: a consideration of the Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeobotanical evidence from northern Greece, in I. Galanaki, H.Tomas, Y.Galanakis and R. Laffineur (Eds.) Between the Aegean and Baltic Seas: Prehistory across Borders, Aegeum 27: 281–293.

Valamoti SM (2009) Η Αρχαιοβοτανική Έρευνα της Διατροφής στην Προϊστορική Ελλάδα (An archaeobotanical investigation of diet in prehistoric Greece). University Studio Press, Thessaloniki

Valamoti SM (2010) H ανθρώπινη δραστηριότητα μέσα από τα φυτά και τις χρήσεις τους στο Αγγελοχώρι κατά την Ύστερη Εποχή του Χαλκού: η συμβολή των αρχαιοβοτανικών δεδομένων (Human activities through plants and their uses at Angelochori during the Late Bronze Age: the contribution of the archaeobotanical evidence), in L. Stefani and N. Merousis (Eds.) Αγγελοχώρι, ένας οικισμός της Ύστερης Εποχής του Χαλκού (Angelochori, a Late Bronze Age Settlement).

Valamoti SM, Anastasaki S (2007) A daily bread—prepared but once a year. Petits Propos Culinaires 84:75–100

Valamoti SΜ, Charles M (2005) Distinguishing food from fodder through the study of charred plant remains: an experimental approach to dung-derived chaff. Veg Hist Archaeobot 14:528–533

Valamoti SM, Jones G (2003) Plant diversity and storage at Mandalo, Macedonia, Greece: archaeobotanical evidence from the final Neolithic and early bronze age. Annu Br Sch Athens 98:1–35

Valamoti SM, Kotsakis K (2007) Transitions to agriculture in the Aegean: the archaeobotanical evidence. In: Colledge S, Conolly J (eds) The origin and spread of domestic plants in SW Asia and Europe. Institute of Archaeology, London, pp 75–92

Valamoti SM, Samuel D, Bayram M, Marinova E (2008) Prehistoric cereal foods from Greece and Bulgaria: investigation of starch microstructure in experimental and archaeological charred remains. Veg Hist Archaeobot 17(suppl 1):265–276

Van Veen AG, Steinkraus KH (1970) Nutritive value and wholesomeness of fermented foods. J Agric Food Chem 18(4):576–578

Van Veen AG, Graham DCW, Steinkraus KH (1969) Fermented milk–wheat combinations. Trop Geogr Med 21:47–52

van Zeist W, Bottema S (1982) Vegetational history of the eastern Mediterranean and the near east during the last 20.000 years. In J. Bintliff and W. van Zeist (eds.), Palaeoclimates, palaeoenvironments and human communities in the Eastern Mediterranean Region in later prehistory, 277–321. B.A.R. S133. Oxford, B.A.R.

Vitelli KD (1989) Were pots first made for foods? Doubts from Franchthi. World Archaeol 21:17–29

Wrangham R (2009) Catching fire: how cooking made us human. Basic Books, New York

Wright JC (2004) A survey of evidence for feasting in Mycenean society. Hesperia 73:133–178

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Glynis Jones who in 1992 pointed out to me the significance of studying those cereal fragments I was painstakingly sorting from my samples. I was lucky enough to subsequently encounter pure concentrations of such fragments which initiated, in 2001, the research presented here. The British School at Athens funded my research on pre-processed cereals through a Centenary Bursary awarded in 2007, while the Institute for Aegean Prehistory has financially supported the study of a large body of archaeobotanical data from northern Greece upon which this paper draws (Archondiko, Apsalos, Promachon/Topolnitsa, between 2002 and 2006). I also wish to thank experts Dr. Delwen Samuel and Prof. Mustafa Bayram who have shared their knowledge on ancient starch and modern cereal food technology, greatly helping with the interpretation of the archaeological finds presented in this paper, Andrea Brandolini and Alyssa Hidalgo for making readily available their research on einkorn food preparations under the MONICA project, Prof. E. Anyfantakis for sending me his publication on Cretan xinochondros and the archaeologists Prof. Angeliki Pilali (†), Prof. Katerina Papanthimou, Dr. Dimitris Grammenos and Stavros Kotsos, Dr. Panikos Chrysostomou and Dr. Liana Stefani who entrusted me with the study of plant remains from their excavations, which, much to my excitement, contained cereal food remains. I am grateful to my students Stela Anastasaki, Efi Tsolaki and Andria Avgousti, together with their grandmothers Chryssi Trakaki, Efthymia Tsolaki and Stavroula Eftychiou, respectively, and to my colleague, Professor Yiorgos Gounaris, and summer neighbour, Roubini Pantazi, who shared with enthousiasm the secrets of preparing trachanas, xinochondros and chachla in various parts of Greece and Cyprus. Thanks (teşekurler) to Dr. Fusun Ertuğ for generously providing and allowing the publication of her photos on bulgur preparation in the village of Kızılkaya in the province of Aksaray in Turkey. I wish to thank Mrs. R. Kapon for permission to publish figure 8d. The Editor of Kritiko Panorama, Mr. Giorgos Patroudakis, kindly provided the images for Figs. 14 and 15d. My colleagues at the Faculty of Philosophy, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Dr. Vassilis Fyntikoglou and Dr. Yannis Xydopoulos, are gratefully acknowledged for their help with translating the texts from Geoponika. Likewise, I am indebted to Andrew Dalby for making available his translation in English of the ancient Greek Γεωπονικά descriptions for χόνδρος and τράγος prior to the publication of his book and to Professor Andrew Tomkins for help with literature related to weaning foods and cereal gruel fermentation. Last but not least, I wish to thank Dr Dorian Fuller as well as two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

I dedicate this paper to the memory of my grandmother, Marika, who was drying her homemade trachanas (of the flour-based type) on the small veranda of her Thessaloniki flat and my mother, Vasso, who desperately resorted to trachanas to feed my skinny brother when we were little. As for me, I re-discovered the trachanas of my childhood as well as bulgur, thanks to the archaeobotanical remains I had to study. As a result, I have introduced both to the repertoire of our daily family meals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valamoti, S.M. Ground cereal food preparations from Greece: the prehistory and modern survival of traditional Mediterranean ‘fast foods’. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 3, 19–39 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-011-0058-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-011-0058-z