Abstract

Purpose of Review

Inflammation is a key player in a wide range of cardiovascular and myocardial diseases. Given the numerous implications of inflammatory processes in disease initiation and progression, functional imaging modalities including positron emission tomography (PET) represent valuable diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring tools in patient management. Since increased glucose metabolism is a hallmark of inflammation, PET using the radiolabeled glucose analog [18F]-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose (FDG) is the mainstay diagnostic test for nuclear imaging of (cardiac) inflammation. Recently, new approaches using more specific tracers to overcome the limited specificity of FDG have emerged.

Recent Findings

PET imaging has proven its value in a number of inflammatory conditions of the heart including myocarditis, endocarditis, sarcoidosis, or reactive changes after myocardial infarction. In infection-related endocarditis, FDG-PET and white blood cell scintigraphy have been implemented in current guidelines. FDG-PET is considered as nuclear medical gold standard in myocarditis, pericarditis, or sarcoidosis. Novel strategies, including targeting of somatostatin receptors or C-X-C motif chemokine receptor CXCR4, have shown promising results in first studies.

Summary

Nuclear medicine techniques offer valuable information in the assessment of myocardial inflammation. Given the possibility to directly visualize inflammatory activity, they represent useful tools for diagnosis, risk stratification, and therapy monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammation contributes to initiation, progression, and healing in various cardiovascular diseases. Its implication has been most thoroughly examined in coronary and vascular atherosclerosis which is now broadly considered an inflammatory disease [1].

Cardiac inflammation can be caused by many different conditions: endocarditis, defined as infection of the endocardial surface of one or more heart valves or of an intracardiac device, has experienced rising incidence in the last decade and is associated with in-hospital mortality rates of 18–23% [2,3,4]. After myocardial infarction, the balance and orchestration of regional and systemic inflammation plays a crucial role in left ventricular remodeling processes and the subsequent risk of the development of heart failure [5]. Myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis, and amyloidosis are under-diagnosed causes of otherwise unexplained cardiomyopathies.

Compared with conventional methods, new noninvasive approaches targeting inflammation have the potential to improve the early detection of myocardial inflammation, enable quantification of disease activity, guide therapeutic interventions, and monitor treatment success. Leukocyte scintigraphy is highly specific for infection because granulocytes are recruited to the site of infection. Whereas general utility has been compromised by limited sensitivity, the implementation of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging has increased diagnostic performance and opened new possibilities in settings in which high specificity is needed, e.g., in endocarditis imaging.

Since increased glucose metabolism is—due to overexpression of glucose transporters and overproduction of glycolytic enzymes in inflammatory cells—considered a hallmark of inflammation, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) using the [18F]-labeled glucose analog 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose (FDG) is the standard of reference for molecular imaging of myocardial inflammation. Indications include endocarditis, myocarditis, or sarcoidosis but as well the detection of inflammatory changes after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, specificity of FDG is hampered by physiological glucose uptake of the myocardium whose suppression requires dedicated patient preparation. In order to overcome limitations of FDG, a number of promising alternatives have recently been introduced including imaging of somatostatin receptors which are overexpressed on the cell surface of activated macrophages [6]. Furthermore, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor CXCR4, which is also overexpressed by leukocytes, plays a role in stem cell trafficking [7, 8], hence representing a suitable target for molecular imaging. Given the specific nature of their signal, these tracers might be used for noninvasive depiction of the temporal and spatial orchestration of myocardial inflammation. It might thereby be possible to directly assess the extent of inflammatory activity, localize sites of activity, identify therapeutic targets, and monitor response to therapy.

Myocardial Infarction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) most commonly results from the acute rupture of a coronary atherosclerotic plaque leading to rapid thrombus formation in the infarct-related epicardial artery and subsequent ischemia distal to the site of occlusion [9•]. As a consequence, a well-orchestrated immune response is activated which is crucial for myocardial repair. Overshooting inflammation however has been shown to be associated with inferior outcomes [10, 11].

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in the clinical setting of AMI can provide information about location and extent of acute myocardial injury as well as left ventricular ejection fraction and end-systolic volume index as important prognostic indicators after AMI [12]. However, no reliable information on inflammatory activity can be obtained. Because of overexpression of glucose transporters and overproduction of glycolytic enzymes in inflammatory cells, PET imaging with FDG is a useful tool in assessing the level of post-AMI inflammation. In experimental models of AMI, FDG-PET has been shown to localize infiltration of metabolically active leukocytes [13, 14•]. Clinical studies supported these findings, providing the opportunity to quantify and monitor metabolic activity in the myocardium after infarction and to gain prognostic information on patient outcome [15, 16•]. The suppression of physiologic FDG-uptake into cardiomyocytes is however mandatory to image monocytes or macrophages and requires patient preparation including low-glucose diet, fasting, and administration of heparin [17, 18]. As potential alternatives to FDG, several novel tracers have been investigated in recent studies: the radiolabeled amino acid [11C]-methionine, routinely used for the characterization of brain tumors and other malignancies, could be demonstrated to serially visualize leukocyte infiltration of inflamed myocardial tissue [19]. Since activated macrophages overexpress somatostatin receptors on the cell surface, the suitability of PET imaging of inflammatory activity using [68Ga]-labeled somatostatin analogs like [68Ga]-DOTA-TATE or [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC has been investigated in a small clinical pilot trial. In comparison to CMR, somatostatin receptor-directed imaging showed a close spatial relation of macrophage concentration to CMR-detected structural changes and might therefore serve as a more specific marker of macrophage activity [20]. However, pre-clinical experiments in mice questioned the usefulness of this approach [21]. Targeting macrophages is also possible by using radiolabeled mannose, an isomer of glucose that is taken up by macrophages through glucose transporters. Additionally, mannose receptors have been described to be expressed on a subset of macrophages [22, 23]. Feasibility of this approach has been shown in atherosclerosis imaging [24•] and may be transferrable also to other settings like AMI.

Another recent approach includes imaging of the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)/stromal cell-derived factor (SDF) -1α axis which has been shown to play a pivotal role in the recruitment and homing of stem- and progenitor cells to the infarct zone [25, 26]. Local up-regulation of CXCR4 in concert with SDF-1α expression after AMI has been demonstrated to be related to stem cell homing and beneficial outcomes [27,28,29,30]. Correspondingly, single systemic treatment with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist, has been shown to result in prolonged bone marrow progenitor cell mobilization and consequently improved recovery from ischemia/reperfusion injury [31]. Additionally, CXCR4 has been described to be routinely expressed on various immune cells and might therefore be involved in the orchestration of the balance between post-infarct inflammation and its resolution [32, 33].

Hence, individual CXCR4 expression after AMI might serve as both a prognostic marker as well as a therapeutic target. Since the advent of a radiolabeled CXCR4-ligand for PET imaging [34] and proof-of-concept for visualization of CXCR4-expression in oncology patients [35,36,37,38], some small studies have tried to investigate the translation of CXCR4-imaging to AMI: local up-regulation of the receptor in the inflamed myocardium as well as in bone marrow and spleen could be demonstrated [39, 40]. Animal models suggested that the imaging signal was mostly created by inflammatory infiltrates as opposed to recruited stem cells (Fig. 1; [40]). Further research to elucidate the potential prognostic and theranostic value of CXCR4 imaging is warranted though.

Validation of [68Ga]-Pentixafor-PET signal in a murine myocardial infarction model. a Autoradiography of short-axis sections at 3 days after myocardial infarction (MI), without (top) and with (bottom) blockade by co-injected AMD3100. Specific [68Ga]-Pentixafor accumulation can be identified in the blue-stained infarct territory (Masson trichrome stain (right)). b CD68 and Ly6G immunostaining (brown) demonstrates infiltration of macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes at 3 days post-MI. c Flow cytometry confirms increased numbers of CD45+ leukocytes in the left ventricle. Reprinted from [40] by permission of Elsevier/JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

Information on underlying pathways that might also be targetable for therapeutic interventions might be obtained by imaging P-selectin using [68Ga]-labeled fucoidan, a polysaccharidic ligand of P-selectin with a nanomolar affinity. General feasibility of this approach has been described for vulnerable plaque imaging but might also be transferable to the setting of AMI [41]. Alternative approaches try to image matrix metalloproteinases that are critical in the pathogenesis of disease [16•, 42] or increased expression of αVβ3 integrin as a marker of cardiac repair using the novel PET probe [18F]-Fluciclatide [43].

Endocarditis

Early diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE) remains challenging. Essentially, IE should be suspected in all patients presenting with fever of unknown origin, particularly if it is associated with laboratory signs of infection, anemia, microscopic hematuria, or septic embolic manifestations. The Modified Duke Criteria as the current gold standard include clinical, microbiological, and echocardiographic findings and have proven an overall sensitivity of about 80% [44•]. However, limitations, especially in patients with prosthetic valves (PV) and implantable cardiac electronic devices (ICED) have been reported [45] and can sum up to 24% of misclassifications [44•]. Advanced imaging techniques for early and sensitive diagnosis of IE are therefore valuable tools in clinical practice. Combining FDG-PET/CT with the Modified Duke Criteria resulted in increased sensitivity with no major change in specificity [46••]. Whereas FDG-PET is unreliable in the setting of native valve endocarditis [47•], it accurately diagnoses prosthetic valve endocarditis and systemic complications of IE [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,•–54]. Acknowledging this utility, in 2015 FDG-PET/CT was included in the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology as a major criterion for diagnosing IE in patients with prosthetic valves [55•]. An option to further improve FDG-PET imaging is the incorporation of CT angiography into the PET/CT scan, resulting in 91% sensitivity, 91% specificity, and 93% positive and 88% negative predictive values [53••]. However, specificity of the method may be limited due to artifacts from metal implants or due to the non-specific biologic tracer signal [56, 57]. As a more specific alternative to FDG-PET/CT, the ESC guidelines included SPECT/CT imaging with radiolabeled autologous white blood cells (WBC). Whereas this technique has proven its value in detection of endocarditis [58,59,60], general application was compromised by limited sensitivity due to a weak signal from the valvular target region and difficult localization of inflammatory foci. The specificity of leukocyte scintigraphy with SPECT/CT could be particularly useful when diagnostic uncertainty remains after echocardiography and FDG-PET/CT, especially in patients who have had cardiac surgery within the past 4 weeks [56, 57, 61, 62].

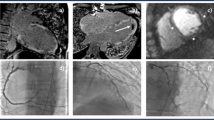

Additionally, the recent advent of a novel SPECT technology which incorporates a sensitive, heart-focused design with the advantages of cadmium-zinc-telluride (CZT) solid-state detectors seems to infer significant improvements in radionuclide imaging. In an elegant approach combining [111In]-labeled WBC imaging with a simultaneously acquired perfusion study to improve localization of inflammatory hot spots relative to the perfusion-defined valve plane, a German group could demonstrate superior imaging quality as well as increased reader confidence for detection of inflammatory foci (Fig. 2; [63•]).

Example of a patient with suspected endocarditis after aortic valve replacement undergoing dual isotope single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) with simultaneous radiolabeled leukocyte and perfusion imaging. Planar white blood cell scans fail to reveal a valvular focus. Conventional SPECT/CT images using radiolabeled leukocytes suggest a hot spot in the region of the artificial valve, but are limited by low counts and noise. Dual isotope images show a focal accumulation adjacent to the implant, consistent with endocarditis (arrows). At surgery, an abscess was identified under the right coronary artery ostium, matching the hot spot on the scan. Reprinted from [62] by permission of Oxford University Press/European Heart Journal

As another possibility to discriminate between infectious and inflammatory causes of endocarditis, new, more bacteria-specific tracers like carbohydrates exclusively metabolized by bacteria or antibodies directed against components of the bacterial cell membrane, e.g., the pilin protein component of the pilin structure of Enterococcus faecalis are being developed [64].

Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device (CIED) Infections Including Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD), Pacemaker-Related and Ventricular Assist Device-Related Infections

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) have been increasingly used over the last years [55•]. Infection rates are reported to be as high as 1–3% and are associated with a 1-year mortality greater than 10% [65]. Whereas echocardiography is the first line imaging modality for the assessment of supposed CIED infection, its use is severely limited in the investigation of extra-cardiac leads and device pockets. Both FDG-PET/CT and leukocyte scintigraphy with SPECT/CT have proven additional value for diagnosis of ICD- or pacemaker-related infections. FDG-PET/CT has been shown to be especially useful for diagnosis of pocket infection (87–91% sensitivity, 93–100% specificity, 97% PPV, 81% NPV), but is less reliable for diagnosis of lead infection or device-related infective endocarditis (24–100% sensitivity, 79–100% specificity, 66–100% PPV, 73–100% NPV) [66,67,68]. Nevertheless, in the clinical context of suspected device-related infection, increased and heterogeneous FDG-uptake along a lead appears to be a reliable sign of active infection [66]. Furthermore, presence of a focal hotspot is considered the best criterion of lead infection [69]. Of note, as with all applications involving FDG, accuracy of the examination depends on patient preparation and the interval post-implantation. Mild, unspecific FDG-uptake in patients with an ICD or pacemaker without suspected infection in the acute phase (≤2 months) after cardiac surgery has been reported [57]. Additionally, attenuation artifacts due to metal implants must be avoided by careful scrutiny of non-attenuation corrected images.

Both FDG-PET/CT and leukocyte scintigraphy with SPECT/CT seem to be beneficial in the diagnosis of ventricular assist device (LVAD)-related infection [70, 71]. FDG-PET/CT is especially sensitive for device infection (Fig. 3). In a small retrospective study, sensitivity for LVAD infection was 100% and specificity 80%. Additionally, in 75% of cases, PET imaging had an impact on patient management [72]. Leukocyte scintigraphy with SPECT/CT in LVAD infection has been reported to yield sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of up to 100% each. Moreover, in 23% of cases, otherwise unsuspected extra-cardiac complications could be revealed [71]. The role of FDG-PET-CT in the investigation of extra-cardiac complications of CIED infection has also been investigated. In a retrospective study in patients with suspected CIED infection, whole-body PET also identified distant septic emboli or metastatic infection in 28% of patients [73]. These results could be confirmed in a prospective study in patients with known lead endocarditis [74]. In this cohort, FDG-PET-CT found septic emboli in 10 patients (29%), including 7 cases of spondylodiscitis, 4 of which were not clinically apparent at that point in time and resulted in significant modifications to therapy.

Value of FDG-PET/CT in left ventricular assist device (LVAD) infection. Display of a 45-year-old male patient with familial non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy status post-LVAD implantation. At 6 months after implantation, the patient reported pain, purulent discharge, and non-healing at the driveline exit site. The driveline culture revealed coagulase-negative staphylococcus aureus and yeast. PET/CT images show intense linear FDG-uptake along the driveline (open arrowhead) and percutaneous exit (solid arrowhead) that is compatible with driveline LVAD infection. The patient underwent revision of the driveline and subsequent urgent heart transplantation due to failed response to antibiotic treatment. Reprinted from [69] by permission of Elsevier/JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

In order to further improve diagnostic accuracy, dual time point protocols for FDG-PET imaging have been proposed. The idea is that imaging at a later time point compensates for background-uptake and might improve accuracy [66, 67, 75]. However, data are limited and studies in other inflammatory and infectious diseases argue against an added value of this approach [76, 77].

Myocarditis

There are many causes for myocarditis, viral infections being the most common. Further etiologies include other types of infections, autoimmune disorders, or drug interactions. The clinical manifestations of myocarditis are highly variable, ranging from subclinical disease to sudden death. The variability in presentation reflects the variability in histological disease severity, etiology, and disease stage at presentation. Myocardial inflammation may be focal or diffuse, involving any or all cardiac chambers. Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is currently the gold standard for diagnosing myocarditis with, however, very low sensitivity of only 20–30% and a significant associated procedural risk [78, 79].

CMR is considered the standard imaging modality in the noninvasive diagnosis of myocarditis as it enables detection of various features of myocarditis, including inflammatory hyperemia and edema, myocyte necrosis and scar, changes in ventricular size and geometry, regional and global wall motion abnormalities, and identification of accompanying pericardial effusion [80]. CMR criteria for diagnosis of myocarditis have been summarized as the so-called Lake Louise criteria [81]. However, CMR has its limitations which are particularly apparent in chronic myocarditis with diagnostic accuracies as low as 50% [82]. Additionally, standard CMR may be insensitive for the detection of inflammatory activity, which is critical for monitoring therapeutic responses to prevent secondary tissue alterations.

FDG-PET/CT—after adequate patient preparation—can visualize acute myocardial inflammation to suggest active myocarditis. PET imaging may help to differentiate between active and chronic disease and working protocols have been established [83,84,85]. In a prospective study enrolling 65 patients with suspected myocarditis, FDG-PET was in good agreement with CMR findings [86]. Given the low yield of random EMB, PET-guided myocardial biopsy may be another application for FDG-PET/CT, as shown for other diseases [87, 88]. CMR and FDG-PET/CT seem complimentary in nature [89] and thus the investigation of the incremental value of integrated PET/MRI for diagnosing myocarditis is an active field of research [84, 90, 91].

In order to overcome limited specificity of FDG, novel PET tracers for imaging of myocarditis are currently investigated. In a rat model of autoimmune myocarditis, feasibility of [11C]-methionine-PET imaging for the detection of cardiac inflammation could recently be demonstrated. Methionine accumulation co-localized with histologically confirmed cardiac inflammatory lesions and [18F]-FDG-uptake, indicating that [11C]-methionine-PET might represent a promising imaging agent for the noninvasive diagnosis of myocarditis (Fig. 4; [92]). Another new approach needing further evaluation includes targeting of somatostatin receptor 2 and has yielded encouraging results in a clinical pilot study [20].

[11C]-methionine-PET in a rodent myocarditis model. a Representative [11C]-methionine-PET images 30 min after intravenous tracer administration. Strong focal cardiac [11C]-methionine-uptake was observed in experimental autoimmune myocarditis (EAM) rats but not in control animals. Extra-cardiac tracer-accumulation in thymus (asterisk) and the liver (arrows) was noted in both EAM and control rats. b Cardiac tracer-uptake in EAM rats (black bar) was significantly higher than that in controls (white bar). c Representative short-axis PET images and time–activity curves of dynamic PET imaging in EAM rat. Ten to 20 min after administration, tracer-uptake increased in heart together with rapid clearance of blood activity. Cardiac signals remained stable for 30–40 min. Gray scale images serve as reference for location of heart. Reprinted from [91] by permission of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine

Pericarditis

The causes of pericarditis, acute or chronic inflammation of the pericardium, are manifold and include infection (viral, bacterial, or fungal), myocardial infarction, trauma, malignancy (primary pericardial neoplasms, pericardial metastasis, or paraneoplastic syndrome), autoimmune and inflammatory disease, or metabolic disturbance (uremia). Pericarditis can also be iatrogenic, either postoperative or as a side effect of medication. Radiation therapy or idiopathic causes are other possible origins. Although the etiology is varying, the pericardium has a relatively non-specific response to these different causes: inflammation of the pericardial layers and increased production of pericardial fluids are the most common and often manifest themselves as chest pain.

Echocardiography as the first line of cardiac imaging in the diagnosis or work-up of pericarditis reveals pericardial effusion, pericardial thickening, and septal bounce. Generally, computed tomography and CMR also permit evaluation of pericardial effusion and thickening and permit better differentiation of pericardium and pericardial fluid [93].

The use of FDG-PET/CT in pericarditis is generally complementary and demonstrates its ability to detect inflammatory tissue even in the absence of obvious anatomical changes [94, 95]. Non-infectious and inflammatory pericarditis presents with a mild to moderate FDG-uptake within the pericardium, with either a diffuse or focal on diffuse pattern of uptake. Only little information is available on the utility of FDG-PET in differential diagnosis of the underlying causes of pericarditis. Some studies reported on the possibility to differentiate infectious/inflammatory pericardial disease from neoplastic/metastatic disease as malignancy often presents with intense metabolic activity [96]. In a retrospective analysis of patients with tuberculous and idiopathic pericarditis, maximum standardized uptake values were significantly higher in tuberculosis patients (13.5 vs. 3.0, P < 0.001) [97]. Constrictive or effusive constrictive pericarditis, an uncommon complication of chemotherapy, can present with mild and diffuse pericardial FDG-uptake [94]. Additionally, pericarditis associated with increased metabolism of the wall of the large vessels like the thoracic or abdominal aorta can be caused by underlying vasculitis [98, 99].

Cardiac Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology. Most commonly affecting lymph nodes and lungs, it can involve any organ system [100]. Though debated, cardiac involvement is more frequent than previously reported [101, 102] and represents one of the leading causes of death by sarcoidosis in Japan and the USA [103]. Due to the multifocal, patchy pattern of myocardial sarcoid involvement, the sensitivity of endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is as low as 20–30% [78]. In clinical practice, the Guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (JMHWG) which include clinical as well as imaging-based criteria serve as the gold standard for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) [104]. Though not included in JMHWG, PET/CT using FDG is by far the most commonly used nuclear medicine imaging technique and has mostly replaced [67Ga]-scintigraphy for assessment of CS [101, 102, 105••, 106].

In comparison to CMR, advantages of FDG-PET (as in other indications) include the biologic nature of the imaging signal, the potential to identify cardiac and extra-cardiac sarcoidosis involvement, and the feasibility of imaging patients with electrical devices or impaired kidney function. Typically, CS manifests as a patchy, focal uptake pattern and FDG-PET/CT has been demonstrated to reliably detect active cardiac and extra-cardiac sarcoidosis with sensitivities of 81–89% and specificities of 78–82%, respectively (Fig. 5; [106, 107]). FDG-PET is thereby often combined with radionuclide perfusion imaging and electrocardiographic gating in order to rule out coronary artery disease or identify resting perfusion defects suggestive of inflammation-induced tissue damage [108, 109]. Additionally, FDG-PET/CT in combination with perfusion imaging has proven its value to determine the prognosis of CS patients [105••], guiding EMB [88] and in predicting response to and monitoring therapy [110]. In the future, combined FDG-PET/CMR imaging may prove beneficial by combining the strengths of both techniques [111].

Classification of cardiac PET/CT perfusion and metabolism imaging. Reprinted from [104] by permission of Elsevier/Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Again, physiologic myocardial FDG-uptake requires dedicated patient preparation to avoid the pitfall of inadequately suppressed basal uptake. Protocols include prolonged fasting, dietary modifications (high-fat, low-carbohydrate meals), or application of heparin prior to imaging [17,113,114,115,, 112–116]. In order to overcome disadvantages of FDG, more specific radiotracers such as somatostatin receptor-ligands have been investigated in small pilot trials (Fig. 6; [117,118,119]). Though very preliminary in nature, other alternatives include hypoxia displaying agents like [18F]-fluoromisonidazole (FMISO) [120] or proliferation markers like 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]-fluorothymidine (FLT) [121].

Macrophage-directed positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) using a somatostatin receptor (SSTR) specific ligand ([68Ga]-DOTA-TOC) in cardiac sarcoidosis. A 54-year-old patient with suspected atypical myocarditis was referred. Coronary artery disease was excluded by coronary angiography. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) revealed acute myocardial damage of the septal and anterior wall in T2 and contrast-enhanced images (a). PET/CT using [68Ga]-DOTA-TOC showed corresponding areas of abnormally increased tracer-uptake consistent with inflammatory changes (b, c; arrows). Additionally, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and pulmonary nodular lesions were documented. Suspected sarcoidosis was confirmed by transbronchial biopsy. Ten months after treatment initiation, a response of pulmonary (d; insert—baseline CT) and cardiac involvement (e, f) could be recorded. Reprinted from [118] by permission of Oxford University Press/European Heart Journal

Cardiac Amyloidosis

Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is a rare form of cardiomyopathy that is characterized by extracellular deposition of fibrils that are composed of low molecular weight subunits of a variety of serum proteins. Although over 25 different amyloidogenic proteins have been described, the three most common types of amyloidosis (defined by their precursor proteins) are light–chain (AL), familial or senile (ATTR), and secondary (AA) amyloidosis. CA most commonly manifests as heart failure, characterized by dyspnea and edema. In its end stage, it presents itself as restrictive cardiomyopathy with a very poor prognosis. Definite diagnosis requires either amyloid deposits on endomyocardial biopsy or, in patients with appropriate cardiac findings, amyloid deposits on histologic examination of a biopsy from other tissues (e.g., abdominal fat pad, rectum, or kidney).

Echocardiography is the initial noninvasive test of choice to diagnose cardiac amyloidosis but suffers from limited specificity [122]. CMR is sensitive and can provide typical pattern of amyloid cardiomyopathy but is strongly limited in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease. Radionuclide bone scintigraphy with technetium-labeled bisphosphonates has long been anecdotally reported to localize to cardiac amyloid deposits. Radionuclide scintigraphy has been reported to be sensitive and specific for imaging cardiac ATTR amyloid and may identify cardiac ATTR amyloid deposits early in the course of the disease [123••, 124]. In a recent multi-center trial including 1217 patients with suspected cardiac amyloidosis, the combination of increased myocardial scintigraphic radiotracer-uptake and the absence of a monoclonal protein in serum or urine had a specificity and positive predictive value for cardiac ATTR amyloidosis of 100% [123••]. However, scintigraphy cannot reliably detect other types of CA and cannot be quantitatively used for therapy monitoring.

As a potential PET substitute for bisphosphonate-based tracers, general feasibility of amyloid imaging using [18F]NaF has been described in single case series whereas another report failed to identify increased tracer uptake in ATTR patients [125,126,127]. Further studies are needed to further investigate the potential value of [18F]NaF PET in CA. Little data available have demonstrated a rather limited role for FDG PET in imaging of CA [128, 129]. To date, the most promising alternatives include more amyloid specific tracers like 11C-labeled Pittsburgh B (PiB) compound [130, 131] as well as 18F-labeled compounds such as Florbetapir [132, 133] and Florbetaben [134]. All studies reported on promising results in diagnosis of CA. Furthermore, since lower myocardial uptake of [11C]PiB in AL amyloidosis patients who had recently undergone chemotherapy for monoclonal gammopathy when compared to patients with CA but no prior chemotherapy could be observed, amyloid-directed PET might also be used in therapy monitoring as a surrogate marker of active light chain deposition in the myocardium [130].

Conclusion

Myocardial inflammation is the endpoint of various different diseases and pathologic conditions. With FDG-PET/CT and leukocyte scintigraphy being the techniques most commonly used, nuclear medical imaging techniques are powerful tools in diagnosis, risk stratification, and therapy monitoring. Novel approaches including bacteria-specific imaging agents, targeting of somatostatin receptors, or C-X-C motif chemokine receptor CXCR4 can help to overcome limitations of standard functional imaging techniques and have demonstrated encouraging results in pilot studies.

References

Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–26.

Chu VH et al. Early predictors of in-hospital death in infective endocarditis. Circulation. 2004;109(14):1745–9.

Hill EE et al. Infective endocarditis: changing epidemiology and predictors of 6-month mortality: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(2):196–203.

Pant S et al. Trends in infective endocarditis incidence, microbiology, and valve replacement in the United States from 2000 to 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2070–6.

Nahrendorf M et al. Imaging systemic inflammatory networks in ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(15):1583–91.

Armani C et al. Expression, pharmacology, and functional role of somatostatin receptor subtypes 1 and 2 in human macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(3):845–55.

Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):610–21.

Pawig L et al. Diversity and inter-connections in the CXCR4 chemokine receptor/ligand family: molecular perspectives. Front Immunol. 2015;6:429.

• Bentzon JF et al. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ Res. 2014;114(12):1852–66. A review comprehensively discussing the mechanisms of atherosclerotic plaque initiation and progression as well as the concepts of plaque burden, activity and vulnerability.

Dimitrijevic O et al. Serial measurements of C-reactive protein after acute myocardial infarction in predicting one-year outcome. Int Heart J. 2006;47(6):833–42.

Prondzinsky R et al. Interleukin-6, −7, −8 and −10 predict outcome in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101(5):375–84.

Kwong RY et al. Detecting acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107(4):531–7.

Jung K et al. Endoscopic time-lapse imaging of immune cells in infarcted mouse hearts. Circ Res. 2013;112(6):891–9.

• Lee WW et al. PET/MRI of inflammation in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(2):153–63. A study investigating the spatial and temporal kinetics of cell recruitment after myocardial infarction.

Rischpler C et al. Prospective evaluation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in postischemic myocardium by simultaneous positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging as a prognostic marker of functional outcome. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(4):e004316.

• Wollenweber T et al. Characterizing the inflammatory tissue response to acute myocardial infarction by clinical multimodality noninvasive imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(5):811–8. A single-center study showing high metabolic rates of glucose in patients after myocardial infarction. Myocardial glucose utilization was associated with splenic and bone marrow activity as sources of inflammatory cells.

Ishimaru S et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(15):1538–43.

Rogers IS et al. Feasibility of FDG imaging of the coronary arteries: comparison between acute coronary syndrome and stable angina. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(4):388–97.

Morooka M et al. 11C-methionine PET of acute myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(8):1283–7.

Lapa C et al. Imaging of myocardial inflammation with somatostatin receptor based PET/CT - a comparison to cardiac MRI. Int J Cardiol. 2015;194:44–9.

Thackeray JT et al. Targeting post-infarct inflammation by PET imaging: comparison of (68)Ga-citrate and (68)Ga-DOTATATE with (18)F-FDG in a mouse model. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(2):317–27.

Bouhlel MA et al. PPARgamma activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 2007;6(2):137–43.

Finn AV et al. Hemoglobin directs macrophage differentiation and prevents foam cell formation in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(2):166–77.

• Tahara N et al. 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-mannose positron emission tomography imaging in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):215–9. A pre-clinical study describing high uptake of 2-deoxy-2-[(18)F]fluoro-D-mannose in atherosclerotic lesions.

Askari AT et al. Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362(9385):697–703.

Shintani S et al. Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103(23):2776–9.

De Falco E et al. SDF-1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia-induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104(12):3472–82.

Saxena A et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha is cardioprotective after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(17):2224–31.

Mayorga M et al. Early upregulation of myocardial CXCR4 expression is critical for dimethyloxalylglycine-induced cardiac improvement in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310(1):H20–8.

Dong F et al. Myocardial CXCR4 expression is required for mesenchymal stem cell mediated repair following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126(3):314–24.

Jujo K et al. CXC-chemokine receptor 4 antagonist AMD3100 promotes cardiac functional recovery after ischemia/reperfusion injury via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. Circulation. 2013;127(1):63–73.

Gupta SK, Pillarisetti K, Lysko PG. Modulation of CXCR4 expression and SDF-1alpha functional activity during differentiation of human monocytes and macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66(1):135–43.

Doring Y et al. The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol. 2014;5:212.

Demmer O et al. PET imaging of CXCR4 receptors in cancer by a new optimized ligand. ChemMedChem. 2011;6(10):1789–91.

Philipp-Abbrederis K et al. In vivo molecular imaging of chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(4):477–87.

Lapa C et al. (68)Ga-Pentixafor-PET/CT for Imaging of Chemokine Receptor 4 Expression in Glioblastoma. Theranostics. 2016;6(3):428–34.

Lapa C et al. [68Ga]Pentixafor-PET/CT for imaging of chemokine receptor 4 expression in small cell lung cancer--initial experience. Oncotarget. 2016;7(8):9288–95.

Vag T et al. First experience with chemokine receptor CXCR4-targeted PET imaging of patients with solid cancers. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(5):741–6.

Lapa C et al. [(68)Ga]pentixafor-PET/CT for imaging of chemokine receptor 4 expression after myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(12):1466–8.

Thackeray JT et al. Molecular imaging of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 after acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(12):1417–26.

Li X et al. Targeting P-selectin by gallium-68-labeled fucoidan positron emission tomography for noninvasive characterization of vulnerable plaques: correlation with in vivo 17.6T MRI. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(8):1661–7.

Sahul ZH et al. Targeted imaging of the spatial and temporal variation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in a porcine model of postinfarct remodeling: relationship to myocardial dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(4):381–91.

Jenkins WS, et al. Cardiac alphaVbeta3 integrin expression following acute myocardial infarction in humans. Heart. 2016.

• Habib G et al. Value and limitations of the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(7):2023–9. A study investigating the value of Duke criteria in patients with pathologically proven infective endocarditis. 24% of patients were misclassified despite the use of Duke criteria.

Thuny F et al. Management of infective endocarditis: challenges and perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):965–75.

•• Saby L et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis: increased valvular 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake as a novel major criterion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2374–82. A prospective study investigating the use of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosing prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE). FDG uptake aorund the site of the prosthetic valve had a global accuracy in diagnosing PVE of 76%.

• Granados U et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in infective endocarditis and implantable cardiac electronic device infection: a cross-sectional study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(11):1726–32. A prospective study investigating the use of FDG-PET/CT for diagnosing infective endocarditis and implantable cardiac electronic device infection. Sensitivity and specificity of PET were 82% and 96%, respectively. PET also identified cases of septic embolism and/or malignancy.

Van Riet J et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT for early detection of embolism and metastatic infection in patients with infective endocarditis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(6):1189–97.

Asmar A et al. Clinical impact of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in the extra cardiac work-up of patients with infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15(9):1013–9.

Balmforth D, Chacko J, Uppal R. Does positron emission tomography/computed tomography aid the diagnosis of prosthetic valve infective endocarditis? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23(4):648–52.

Bonfiglioli R et al. (1)(8)F-FDG PET/CT diagnosis of unexpected extracardiac septic embolisms in patients with suspected cardiac endocarditis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(8):1190–6.

Ozcan C et al. The value of FDG-PET/CT in the diagnostic work-up of extra cardiac infectious manifestations in infectious endocarditis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(7):1629–37.

•• Pizzi MN et al. Improving the diagnosis of infective endocarditis in prosthetic valves and intracardiac devices with 18F-fluordeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography angiography: initial results at an Infective Endocarditis Referral Center. Circulation. 2015;132(12):1113–26. A single-center study demonstrating improved accuracy in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and prosthetic valves or cardiac devices by use of FDG-PET/CT. Addition of CT angiography yielded additional benefit.

Lancellotti P et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in device infective endocarditis: ready for prime time. Circulation. 2015;132(12):1076–80.

• Habib G et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–128. Recent guidelines stressing the value of FDG-PET/CT in diagnosis of infective endocarditis.

Millar BC et al. 18FDG-positron emission tomography (PET) has a role to play in the diagnosis and therapy of infective endocarditis and cardiac device infection. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1724–36.

Sarrazin JF et al. Usefulness of fluorine-18 positron emission tomography/computed tomography for identification of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(18):1616–25.

Cerqueira MD, Jacobson AF. Indium-111 leukocyte scintigraphic detection of myocardial abscess formation in patients with endocarditis. J Nucl Med. 1989;30(5):703–6.

Erba PA et al. Radiolabeled WBC scintigraphy in the diagnostic workup of patients with suspected device-related infections. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(10):1075–86.

Rouzet F et al. Respective performance of 18F-FDG PET and radiolabeled leukocyte scintigraphy for the diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(12):1980–5.

Adjtoutah D et al. Advantages of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography in detecting post cardiac surgery infections. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2014;26(1):57–61.

Thuny F et al. Reply: positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(2):187–9.

• Caobelli F, et al. Simultaneous dual-isotope solid-state detector SPECT for improved tracking of white blood cells in suspected endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2016. A single center study demonstrating the feasiblity of simultaneous perfusion and inflammation imaging in suspected endocarditis.

Pinkston KL et al. Antibody guided molecular imaging of infective endocarditis. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1535:229–41.

Tarakji KG et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device infections: presentation, management, and patient outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(8):1043–7.

Cautela J et al. Diagnostic yield of FDG positron-emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with CEID infection: a pilot study. Europace. 2013;15(2):252–7.

Leccisotti L et al. Cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection: delayed vs standard FDG PET-CT imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21(3):622–32.

Bensimhon L et al. Whole body [(18) F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for the diagnosis of pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator infection: a preliminary prospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(6):836–44.

Yeh CL et al. Infective endocarditis detected by (1)(8)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in a patient with occult infection. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27(11):528–31.

Kim J et al. FDG PET/CT imaging for LVAD associated infections. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(8):839–42.

Litzler PY et al. Leukocyte SPECT/CT for detecting infection of left-ventricular-assist devices: preliminary results. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(7):1044–8.

Dell'Aquila AM et al. Contributory role of fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the diagnosis and clinical management of infections in patients supported with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):87–94. discussion 94.

Tlili G et al. High performances of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT in cardiac implantable device infections: a study of 40 patients. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22(4):787–98.

Amraoui S et al. Contribution of PET imaging to the diagnosis of septic embolism in patients with pacing lead endocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(3):283–90.

Caldarella C et al. Which is the optimal acquisition time for FDG PET/CT imaging in patients with infective endocarditis? J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20(2):307–9.

Glaudemans AW, Israel O, Slart RH. Pitfalls and limitations of radionuclide and hybrid imaging in infection and inflammation. Semin Nucl Med. 2015;45(6):500–12.

De Winter F et al. Promising role of 18-F-fluoro-D-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in clinical infectious diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21(4):247–57.

Cooper LT et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(24):3076–93.

Hauck AJ, Kearney DL, Edwards WD. Evaluation of postmortem endomyocardial biopsy specimens from 38 patients with lymphocytic myocarditis: implications for role of sampling error. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64(10):1235–45.

Friedrich MG, Marcotte F. Cardiac magnetic resonance assessment of myocarditis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):833–9.

Friedrich MG et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: A JACC White Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(17):1475–87.

Lurz P et al. Diagnostic performance of CMR imaging compared with EMB in patients with suspected myocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(5):513–24.

Ozawa K et al. Determination of optimum periods between onset of suspected acute myocarditis and (1)(8)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the diagnosis of inflammatory left ventricular myocardium. Int J Cardiol. 2013;169(3):196–200.

Takano H et al. Active myocarditis in a patient with chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130(1):e11–3.

von Olshausen G et al. Detection of acute inflammatory myocarditis in Epstein Barr virus infection using hybrid 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2014;130(11):925–6.

Nensa F, et al. Feasibility of FDG-PET in myocarditis: comparison to CMR using integrated PET/MRI. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016.

Guralnik L et al. Metabolic PET/CT-guided lung lesion biopsies: impact on diagnostic accuracy and rate of sampling error. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(4):518–22.

Simonen P et al. F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-guided sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(10):1581–5.

Piriou N et al. Utility of cardiac FDG-PET imaging coupled to magnetic resonance for the management of an acute myocarditis with non-informative endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(5):574.

Nensa F et al. Hybrid PET/MR imaging of the heart: feasibility and initial results. Radiology. 2013;268(2):366–73.

Nensa F et al. Multiparametric assessment of myocarditis using simultaneous positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(32):2173.

Maya Y et al. 11C-methionine PET of myocardial inflammation in a rat model of experimental autoimmune myocarditis. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(12):1985–90.

Alter P et al. MR, CT, and PET imaging in pericardial disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18(3):289–306.

Losik SB, Studentsova Y, Margouleff D. Chemotherapy-induced pericarditis on F-18 FDG positron emission tomography scan. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(11):913–5.

Salomaki SP et al. Visualization of pericarditis by fluorodeoxyglucose PET. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15(3):291.

Shao D et al. Differentiation of malignant from benign heart and pericardial lesions using positron emission tomography and computed tomography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18(4):668–77.

Dong A et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT in differentiating acute tuberculous from idiopathic pericarditis: preliminary study. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(4):e160–5.

Couturier B, Huyge V, Soyfoo MS. Pericarditis revealing large vessel vasculitis. ISRN Rheumatol. 2011;2011:648703.

Patel D et al. Sarcoid pericarditis and large vessel vasculitis detected on FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41(8):661–3.

Baughman RP et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 Pt 1):1885–9.

Mehta D et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008;133(6):1426–35.

Patel MR et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation. 2009;120(20):1969–77.

Gideon NM, Mannino DM. Sarcoidosis mortality in the United States 1979–1991: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):423–7.

Soejima K, Yada H. The work-up and management of patients with apparent or subclinical cardiac sarcoidosis: with emphasis on the associated heart rhythm abnormalities. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20(5):578–83.

•• Blankstein R et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(4):329–36. Single-center study demonstrating the prognostic value of FDG-PET/CT in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Presence of focal FDG uptake on cardiac PET identified patients at higher risk of death or ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Youssef G et al. The use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis including the Ontario experience. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(2):241–8.

Tang R et al. Impact of patient preparation on the diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET in cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41(7):e327–39.

McArdle B et al. Cardiac PET: metabolic and functional imaging of the myocardium. Semin Nucl Med. 2013;43(6):434–48.

Schatka I, Bengel FM. Advanced imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(1):99–106.

Hulten E et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016;6(1):50–63.

Schneider S et al. Utility of multimodal cardiac imaging with PET/MRI in cardiac sarcoidosis: implications for diagnosis, monitoring and treatment. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(5):312.

Ambrosini V et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT for the assessment of disease extension and activity in patients with sarcoidosis: results of a preliminary prospective study. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(4):e171–7.

Harisankar CN et al. Utility of high fat and low carbohydrate diet in suppressing myocardial FDG uptake. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18(5):926–36.

Ito K et al. Efficacy of heparin loading during an 18F-FDG PET/CT examination to search for cardiac sarcoidosis activity. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(2):128–30.

Mc Ardle BA et al. The role of F(18)-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in guiding diagnosis and management in patients with known or suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20(2):297–306.

Williams G, Kolodny GM. Suppression of myocardial 18F-FDG uptake by preparing patients with a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(2):W151–6.

Lapa C, et al. Somatostatin receptor based PET/CT in patients with the suspicion of cardiac sarcoidosis: an initial comparison to cardiac MRI. Oncotarget. 2016.

Gormsen LC et al. A dual tracer (68)Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and (18)F-FDG PET/CT pilot study for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2016;6(1):52.

Reiter T et al. Detection of cardiac sarcoidosis by macrophage-directed somatostatin receptor 2-based positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(35):2404.

Manabe O, et al. 18F-fluoromisonidazole (FMISO) PET may have the potential to detect cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016.

Norikane T et al. 18F-FLT PET imaging in a patient with sarcoidosis with cardiac involvement. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40(5):433–4.

Carroll JD, Gaasch WH, McAdam KP. Amyloid cardiomyopathy: characterization by a distinctive voltage/mass relation. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49(1):9–13.

•• Gillmore JD et al. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2404–12. Multi-center trial demonstrating the feasibility of nonbiopsy diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis by means of scintigraphy and serum analysis (to rule out monoclonal gammopathy).

Glaudemans AW et al. Bone scintigraphy with (99m)technetium-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate allows early diagnosis of cardiac involvement in patients with transthyretinderived systemic amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2014;21(1):35–44.

Van Der Gucht A et al. [18F]-NaF PET/CT imaging in cardiac amyloidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23(4):846–9.

Gagliardi C, et al. Does the etiology of cardiac amyloidosis determine the myocardial uptake of [18F]-NaF PET/CT? J Nucl Cardiol. 2016.

Trivieri MG et al. 18F-sodium fluoride PET/MR for the assessment of cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(24):2712–4.

Kung J et al. Intense fluorodeoxyglucose activity in pulmonary amyloid lesions on positron emission tomography. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(12):975–6.

Mekinian A et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with amyloid light-chain amyloidosis: caseseries and literature review. Amyloid. 2012;19(2):94–8.

Lee SP et al. 11C-Pittsburgh B PET imaging in cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1):50–9.

Pilebro B et al. Positron emission tomography (PET) utilizing Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) for detection of amyloid heart deposits in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR). J Nucl Cardiol. 2016.

Dorbala S et al. Imaging cardiac amyloidosis: a pilot study using (1)(8)F-florbetapir positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(9):1652–62.

Osborne DR et al. A routine PET/CT protocol with streamlined calculations for assessing cardiac amyloidosis using (18)F-florbetapir. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2015;2:23.

Law WP et al. Cardiac amyloid imaging with 18F-florbetaben PET: a pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(11):1733–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

MK and CL declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and were in compliance with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiac Nuclear Imaging

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12410-017-9413-5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kircher, M., Lapa, C. Novel Noninvasive Nuclear Medicine Imaging Techniques for Cardiac Inflammation. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 10, 6 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-017-9400-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-017-9400-x