Abstract

The main objective of this paper is to propose a tool for measuring the productivity and performance gaps across a set of Decision Making Units for monitoring their evolution and analyzing their components over time. To do this, we use the approach proposed by Aparicio and Santín (Eur J Oper Res 267(1):227–235, 2018) which is grounded on a base-group base-period productivity index and Data Envelopment Analysis. Additionally, we propose a new index for measuring the performance gap between two or more groups of production units and its decomposition in effectiveness gap and outcome possibility set gap. As an empirical illustration of the approach, we focus our attention on the educational sector. In particular, we analyze six Latin American countries over time. For this purpose, we rely on OECD–PISA data aggregated at school level. Over the period 2006–2018, performance and productivity followed very different paths in each country showing that the correlation between school performance and productivity is very low. Therefore, we suggest that the simultaneous analysis of performance and productivity gaps together with their evolution over time is a must in order to benchmark countries and monitor improvements and weaknesses in education systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Outcomes used to measure effectiveness are all average test scores. To measure efficiency, we take into account the same outcomes defined in the same way in order to ensure comparability, and resources are defined per capita (per student) or as a ratio. Throughout this paper efficiency and effectiveness measures are the bricks for calculating performance and productivity gaps.

Note that here we use the terms “outputs” and “inputs” to refer to “outcomes” and “resources”, respectively. The idea is to respect the traditional presentation in the efficiency literature and the generality of the methodology. As already mentioned in the empirical analysis, outcomes and resources are measured as per capita values and ratios.

Test scores in Latin America are below the average of OECD countries. For this reason, we consider that an output orientation is more appealing for policy makers interested in maximizing students’ achievements subject to their budget constraints.

For Mbuvi et al. (2012), effectiveness versus efficiency can be also loosely stated as “doing the right things” versus “doing things right”.

In education, it is meaningful to compare the productivity and the performance of groups of schools in different environments, as well as different regions inside the same country, different countries with similar economic features (as in this study) or with different regulatory conditions, according to school ownership (public vs. private), religion (catholic vs. non-catholic) or location (urban vs. rural), for example. Recently, Amado et al. (2018) compare the gender pay gap using a similar approach.

Note at this point that all the indexes introduced in this section calculate productivity gaps and their evolution with respect to the efficiency dimension, i.e. including inputs and outputs for measuring distances. The same indexes for the effectiveness dimension are defined and explained in Sect. 2.3.

In this paper we assume a CRS technology for avoiding the infeasibility issue (Lovell, 2003). Moreover, in our empirical application scale is not a major issue because education is produced at classroom level and outputs and inputs variables are usually averaged or normalized for avoiding size issues.

Another key dimension of countries’ educational outcomes is children’s enrollment rates at secondary schools. Unfortunately, this dimension cannot be considered in this study given that the information is not available at school level in PISA.

Two other Latin American countries, Costa Rica and Peru, participated in PISA 2012 and 2018, but not in PISA 2006. This is the reason why they were not included in this analysis. In 2021, four other Latin American countries will join the PISA project: El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica and Paraguay.

Ideally, the reference should be chosen by agreement by all evaluated groups. As a rule of thumb, the reference should be recognized as a medium-term target with comparable sample size and as similar as possible in culture and legal framework.

World Development Indicators from the World Bank (2020) report the secondary education enrollment evolution for the period 2006 to 2018 in these countries, as follows: 79.1% to 89.5% (2016) in Argentina; 73.2% (2007) to 81.7% (2017) in Brazil; 89.9% to 86.8% (2017) in Chile; 68.9% to 77.4% in Colombia; 67.8% to 81.2% (2017) in Mexico; and 67.6% (2007) to 88.2% (2017) in Uruguay. In Portugal, the reference country, the evolution over the same period was from 82.6% to 94.7%.

Note that this is also the case for Portugal in 2012 and 2018.

It is important to highlight that from now on all performance and productivity gaps and gaps changes results are obtained with the distances of Table 3 using equations from 5 to 16. For example, from Table 4 PGI we know that the performance gap between, let say, Uruguay and Argentina is 1.026 for 2018. This is the result of using Eq. (12). We divide the average effectiveness of Uruguayan schools with respect to Portugal 2006, according to Table 3 this value is 0.700, by the same distance for Argentina, 0.682. As for presentation purposes all values were rounded to three decimals, direct operations could bring about slight differences in the third decimal.

Note that under this approach it is also possible to compare the mean behavior of Portuguese schools in 2006 against their own technology. Obviously, in this case for Portugal 2006 all the distance with respect to the technology is explained by the efficiency component.

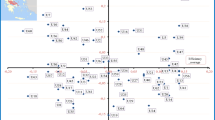

Note that applying the circularity property of Eqs. (10), (11), (15) and (16), the exact coordinates for dots plotted in Figs. 2, 3 and 4 showing all performance and productivity changes and their decompositions between 2006 and 2018 are obtained multiplying the main diagonal in Tables 6 and 8 (2006–2012 changes) by the main diagonal in Tables 7 and 9 (2012–2018 changes) respectively. The values outside the main diagonals in Tables from 6, 7, 8 and 9 represent the distances between them.

References

Afonso A, St Aubyn M (2006) Cross-country efficiency of secondary education provision: a semi-parametric analysis with non-discretionary inputs. Econ Model 23(3):476–491

Amado CA, Santos SP, São José JM (2018) Measuring and decomposing the gender pay gap: a new frontier approach. Eur J Oper Res 271(1):357–373

Amado CAF, Barreira AP, Santos SP, Guimarães MH (2019) Comparing the quality of life of cities that gained and lost population: an assessment with DEA and the Malmquist index. Pap Region Sci 98(5):2075–2097

Aparicio J, Santín D (2018) A note on measuring group performance over time with pseudo-panels. Eur J Oper Res 267(1):227–235

Aparicio J, Crespo-Cebada E, Pedraja-Chaparro F, Santín D (2017) Comparing school ownership performance using a pseudo-panel database: a Malmquist–type index approach. Eur J Oper Res 256:533–542

Aristovnik A (2012) The relative efficiency of education and R&D expenditures in the new EU member states. J Bus Econ Manag 13(5):832–848

Aristovnik A, Obadić A (2014) Measuring relative efficiency of secondary education in selected EU and OECD countries: the case of Slovenia and Croatia. Technol Econ Dev Econ 20(3):419–433

Berg SA, Førsund FR, Jansen ES (1992) Malmquist indices of productivity growth during the deregulation of Norwegian Banking, 1980–89. Scand J Econ 94((Supplement)):211–228

Camanho AS, Dyson RG (2006) Data envelopment analysis and Malmquist indices for measuring group performance. J Prod Anal 26:35–49

Charnes A, Cooper WW, Rhodes E (1978) Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur J Oper Res 2:429–444

Cherchye L, Moesen W, Puyenbroeck T (2004) Legitimately diverse, yet comparable: on synthesizing social inclusion performance in the EU. JCMS J Common Mark Stud 42(5):919–955

Cherchye L, De Witte K, Perelman S (2019) A unified productivity-performance approach applied to secondary schools. J Oper Res Soc 70(9):1522–1537

Cordero JM, Polo C, Santín D, Simancas R (2018) Efficiency measurement and cross-country differences among schools: a robust conditional nonparametric analysis. Econ Model 74:45–60

De Jorge J, Santín D (2010) Determinantes de la eficiencia educativa en la Unión Europea. Hacienda Pública Española 193:131–155

De Witte K, López-Torres L (2017) Efficiency in education: a review of literature and a way forward. J Oper Res Soc 68(4):339–363

Deutsch J, Dumas A, Silber J (2013) Estimating an educational production function for five countries of Latin America on the basis of the PISA data. Econ Educ Rev 36:245–262

Farrell MJ (1957) The measurement of productive efficiency. J R Stat Soc Ser A (General) 120(3):253–290

Ferreira D, Marques RC (2015) Did the corporatization of Portuguese hospitals significantly change their productivity? Eur J Health Econ 16(3):289–303

Ganzeboom H, De Graaf P, Treiman J, De Leeuw J (1992) A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Soc Sci Res 21(1):1–56

Hanushek EA, Kimko DD (2000) Schooling, labor-force quality, and the growth of nations. Am Econ Rev 90(5):1184–1208

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2008) The role of cognitive skills in economic development. J Econ Liter 46(3):607–668

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2011a) The economics of international differences in educational achievement. Handbook of the Economics of Education, vol 3. Elsevier, New York, pp 89–200

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2011b) How much do educational outcomes matter in OECD countries? Econ Policy 26(67):427–491

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2012) Schooling, educational achievement, and the Latin American growth puzzle. J Dev Econ 99(2):497–512

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2020) Education, knowledge capital, and economic growth. The Economics of Education, 2nd edn. Academic Press, New York, pp 171–182

Hanushek EA, Link S, Woessmann L (2013) Does school autonomy make sense everywhere? Panel estimates from PISA. J Dev Econ 104:212–232

Kaarsen N (2014) Cross-country differences in the quality of schooling. J Dev Econ 107:215–224

Lovell CAK (2003) The decomposition of Malmquist productivity indexes. J Prod Anal 20:437–458

Lovell CAK, Pastor JT (1999) Radial DEA models without inputs or without outputs. Eur J Oper Res 118:46–51

Mbuvi D, De Witte K, Perelman S (2012) Urban water sector performance in Africa: a stepwise bias-corrected efficiency and effectiveness analysis. Util Policy 22:31–40

Melyn W, Moesen W (1991) Towards a synthetic indicator of macroeconomic performance: unequal weighting when limited information is available. Public Economics Research Paper No. 17, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

OECD (1999) Classifying educational programmes, Manual for ISCED-97 implementation in OECD countries. OECD, Paris

OECD (2005) Handbook on constructing composite indicators. OECD, Paris

OECD (2013) PISA 2012 assessment and analytical framework: mathematics, reading, science, problem solving and financial literacy. PISA. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2014a). PISA 2012 results: What students know and can do. Student performance in mathematics, reading and science: Vol I. OECD Publishing, revised edition, PISA

OECD (2014b). PISA 2012 Technical Report. OECD Publishing

Prieto AM, Zofio JL (2001) Evaluating effectiveness in public provision of infrastructure and equipment: the case of Spanish municipalities. J Prod Anal 15(1):41–58

Santín D, Sicilia G (2015) Measuring the efficiency of public schools in Uruguay: main drivers and policy implications. Latin Am Econ Rev 24:5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40503-015-0019-5

Thanassoulis E, Shiraz RK, Maniadakis N (2015) A cost Malmquist productivity index capturing group performance. Eur J Oper Res 241(3):796–805

Thieme C, Giménez V, Prior D (2012) A comparative analysis of the efficiency of national education systems. Asia Pac Educ Rev 13(1):1–15

Vaz CB, Camanho AS (2012) Performance comparison of retailing stores using a Malmquist-type index. J Oper Res Soc 63(5):631–645

World Bank (2020) World Development Indicators. (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators)

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive comments and help in improving the contents and presentation of this paper. Additionally, J. Aparicio thanks the Spanish Ministry for Economy and Competitiveness (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad), the State Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigacion) and the European Regional Development Fund (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional) for financial support under grant PID2019-105952GB-I00 (AEI/FEDER, UE). D. Santín acknowledges funding received from the Spanish Ministry for Economy and Competitiveness (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad) project referenced ECO2017-83759-P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aparicio, J., Perelman, S. & Santín, D. Comparing the evolution of productivity and performance gaps in education systems through DEA: an application to Latin American countries. Oper Res Int J 22, 1443–1477 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00578-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00578-2