Abstract

Background

18F-NaF PET/CT identifies high-risk plaques due to active calcification in coronary arteries with potential to characterize plaques in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) and chronic stable angina (CSA) patients.

Methods

Twenty-four MI and 17 CSA patients were evaluated with 18F-NaF PET/CTCA for SUVmax and TBR values of culprit and non-culprit plaques in both groups (inter-group and intra-group comparison), and pre- and post-interventional MI plaques sub-analysis.

Results

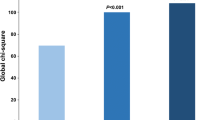

Culprit plaques in MI patients had significantly higher SUVmax (1.6; IQR 0.6 vs 1.3; IQR 0.3, P = 0.03) and TBR (1.4; IQR 0.6 vs 1.1; IQR 0.4, P = 0.006) than culprit plaques of CSA. Pre-interventional culprit plaques of MI group (n = 11) revealed higher SUVmax (P = 0.007) and TBR (P = 0.008) values than culprit CSA plaques. Culprit plaques showed significantly higher SUVmax (P = 0.006) and TBR (P = 0.0003) than non-culprit plaques in MI group, but without significant difference between culprit and non-culprit plaques in CSA group. With median TBR cutoff value of 1.4 in MI culprit plaques, 6/7 plaques (85.7%) among the event prone non-culprit lesions had TBR values > 1.4 in CSA group.

Conclusion

The study shows higher SUVmax and TBR values in MI culprit plaques and comparable TBR values for event prone plaques of CSA group in identifying high-risk plaques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- CSA:

-

Chronic stable angina

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- CTCA:

-

Computed tomography coronary angiography

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- CTAC:

-

CT attenuation correction

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- SUV:

-

Standardized uptake value

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- LCX:

-

Left circumflex artery

- IVUS:

-

Intravascular ultrasound

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

- ECHO:

-

Echocardiography

References

Falk E. Why do plaques rupture? Circulation. 1992;86(6 Suppl):30–42.

Stone GW, Maehara A, Mintz GS. The reality of vulnerable plaque detection. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:902–4.

Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. CurrProblCardiol. 2010;35:72–115.

Fleg JL, Stone GW, Fayad ZA, Granada JF, Hatsukami TS, Kolodgie FD, et al. Detection of high-risk atherosclerotic plaque. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;59:941–55.

Fayad ZA, Fuster V. Clinical imaging of the high-risk or vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2001;89:305–16.

Sadeghi MM, Glover DK, Lanza GM, Fayad ZA, Johnson LL. Imaging atherosclerosis and vulnerable plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(Suppl 1):51S–65S.

Sandfort V, Lima JAC, Bluemke DA. Noninvasive imaging of atherosclerotic plaque progression. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e003316.

Pozo E, Agudo-Quilez P, Rojas-González A, Alvarado T, Olivera MJ, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of vulnerable coronary plaque. World J Cardiol. 2016;8:520–33.

Sun Z-H, Rashmizal H, Xu L. Molecular imaging of plaques in coronary arteries with PET and SPECT. J GeriatrCardiol. 2014;11:259–73.

Moise A, Clement B, Saltiel J. Clinical and angiographic correlates and prognostic significance of the coronary extent score. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:1255–9.

Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8 Suppl):C13–8.

Vesey AT, Jenkins WS, Irkle A, Moss A, Sng G, Forsythe RO, et al. 18 F-fluoride and 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography after transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;1:e004976.

Joshi NV, Vesey A, Newby DE, Dweck MR. Will 18F-sodium fluoride PET-CT imaging be the magic bullet for identifying vulnerable coronary atherosclerotic plaques? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(9):521.

Chaudhary R, Chauhan A, Singhal M, Bagga S. Risk factor profiling and study of atherosclerotic coronary plaque burden and morphology with coronary computed tomography angiography in coronary artery disease among young Indians. Int J Cardiol. 2017;240:452–7.

Rudd JHF. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:2708–11.

Derlin T, Toth Z, Papp L, Wisotzki C, Apostolova I, Habermann CR, et al. Correlation of inflammation assessed by 18F-FDG PET, active mineral deposition assessed by 18F- fluoride PET, and vascular calcification in atherosclerotic plaque: a dual-tracer PET/CT study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1020–7.

Ben-Haim S, Kupzov E, Tamir A, Israel O. Evaluation of 18F-FDG uptake and arterial wall calcifications using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1816–21.

Menezes LJ, Kotze CW, Agu O, Richards T, Brookes J, Goh VJ, et al. Investigating vulnerable atheroma using combined 18F-FDG PET/CT angiography of carotid plaque with immunohistochemical validation. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1698–703.

Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, Shah ASV, Calvert PA, Craighead FHM, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383:705–13.

Shioi A, Ikari Y. Plaque calcification during atherosclerosis progression and Regression. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25:294–303.

Ehara S. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–9.

ElFaramawy A, Youssef M, Abdel Ghany M, Shokry K. Difference in plaque characteristics of coronary culprit lesions in a cohort of Egyptian patients presented with acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease: an optical coherence tomography study. Egypt Heart J. 2018;70:95–100.

Tavakoli S, Sadeghi MM. 18F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography and plaque calcification. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e008712.

Creager MD, Hohl T, Hutcheson JD, Moss AJ, Schlotter F, Blaser MC, et al. 18F-Fluoride signal amplification identifies microcalcifications associated with atherosclerotic plaque instability in positron emission tomography/computed tomography images. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e007835.

Irkle A, Vesey AT, Lewis DY, Skepper JN, Bird JLE, Dweck MR, et al. Identifying active vascular microcalcification by 18F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7495.

Ferreira MJV, Oliveira-Santos M, Silva R, Gomes A, Ferreira N, Abrunhosa A, et al. Assessment of atherosclerotic plaque calcification using F18-NaF PET-CT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:1733–41.

Maldonado N, Kelly-Arnold A, Vengrenyuk Y, Laudier D, Fallon JT, Virmani R, et al. A mechanistic analysis of the role of microcalcifications in atherosclerotic plaque stability: potential implications for plaque rupture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(5):H619–28.

Vengrenyuk Y, Cardoso L, Weinbaum S. Micro-CT based analysis of a new paradigm for vulnerable plaque rupture: cellular microcalcifications in fibrous caps. Mol Cell Biomech. 2008;5:37–47.

Vengrenyuk Y, Carlier S, Xanthos S, Cardoso L, Ganatos P, Virmani R, et al. A hypothesis for vulnerable plaque rupture due to stress-induced debonding around cellular microcalcifications in thin fibrous caps. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:14678–83.

Giannopoulos AA, Benz DC, Gräni C, Buechel RR. Imaging the event-prone coronary artery plaque. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;26:141–53.

Bellinge JW, Francis RJ, Majeed K, Watts GF, Schultz CJ. In search of the vulnerable patient or the vulnerable plaque: 18 F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography for cardiovascular risk stratification. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:1774–83.

Yahagi K, Joner M, Virmani R. The mystery of spotty calcification; can we solve it by optical coherence tomography? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004252.

Shi X, Gao J, Lv Q, Cai H, Wang F, Ye R, et al. Calcification in atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability: friend or foe? Front. Physiol. 2020;11:56.

Li Z-N, Yin W-H, Lu B, Yan H-B, Mu C-W, Gao Y, et al. Improvement of image quality and diagnostic performance by an innovative motion-correction algorithm for prospectively ECG triggered coronary CT angiography. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0142796.

Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, Takx RA, Vilstrup MH, Hess S, Nielson AL, et al. Delayed sodium 18F-fluoride PET/CT imaging does not improve quantification of vascular calcification metabolism: results from the CAMONA study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:293–304.

Disclosure

Drs Abhiram G. Ashwathanarayana, SwayamjeetSatapathy, Ashwani Sood, Manphool Singhal, Bhagwant Rai Mittal, Rohit Manoj Kumar, Darshan Krishnappa, Nivedita Rana and Mr. Madan Parmar have nothing to disclose. No financial support was received for the publication of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors of this article have provided a PowerPoint file, available for download at SpringerLink, which summarises the contents of the paper and is free for re-use at meetings and presentations. Search for the article DOI on SpringerLink.com.

The authors have also provided an audio summary of the article, which is available to download as ESM, or to listen to via the JNC/ASNC Podcast.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ashwathanarayana, A.G., Singhal, M., Satapathy, S. et al. 18F-NaF PET uptake characteristics of coronary artery culprit lesions in a cohort of patients of acute coronary syndrome with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and chronic stable angina: A hybrid fluoride PET/CTCA study. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 29, 558–568 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-020-02284-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-020-02284-0