Abstract

The treat-to-target strategy, which defines clinical remission as the primary therapeutic goal for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), is a widely recommended treatment approach in clinical guidelines. Achieving remission has been associated with improved clinical outcomes, quality of life, and productivity. These benefits are likely to translate to reduced economic burden in terms of lower healthcare costs and resource utilization. As such, a literature review was conducted to better understand the economic value of remission. Despite the large heterogeneity found in RA-related economic outcomes across studies, patients in remission consistently had lower direct medical and indirect costs, less healthcare resource utilization, and greater productivity compared to those without remission. Remission was associated with 19–52% savings in direct medical costs and 37–75% savings in indirect costs. The economic value of remission should thus be considered in economic analyses of RA therapies to inform treatment and reimbursement decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Achieving remission has been associated with improved clinical outcomes, quality of life, and productivity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA); however, the associated economic benefits are less understood. |

This review provides an overview of clinical, humanistic, economic value of clinical remission, with a focus on quantifying remission-associated economic benefits, which could be used to better characterize the economic profile of RA treatments. |

Achieving clinical remission was found to promote better disease control and was associated with substantial economic benefits. |

Remission was associated with 19–52% reduction in direct medical costs and 37–75% savings in indirect costs, compared with not achieving remission. |

The economic benefit of remission is an important component to consider when conducting economic analyses of RA therapies to inform treatment and reimbursement decisions. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common immune-mediated inflammatory arthritis, affecting approximately 5 per 1000 adults worldwide [1]. RA has a significant negative impact on daily activities, including work and household tasks, and is associated with high burden and impaired quality of life (QoL) [1, 2].

During recent decades, the target of RA treatment has changed from symptomatic relief to clinical remission, which slows down radiologic damage and prevents disability [3, 4]. Emerging treatments, including biologics and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, have transformed the management of RA to the extent that remission is a reasonable expectation and is now a major therapeutic target to guide treatment in clinical practice [4, 5].

Multiple definitions of clinical remission are endorsed in clinical guidelines, including remission based on Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), and Boolean criteria [4, 6, 7]. Among them, DAS28 is the most commonly used remission definition in clinical practice, as well as in clinical trials [8,9,10,11], and can also be further characterized by incorporating composite parameters like C-reactive protein (i.e., DAS28-CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rates (i.e., DAS28-ESR) [12]. Nevertheless, all these remission definitions are useful outcome measures to characterize disease status. Despite the debate regarding which remission definition should be used as the treatment target, achieving remission has been associated with improved clinical outcomes, patient QoL, and productivity [13,14,15].

Additionally, achieving and maintaining remission is likely to be associated with substantial economic benefits due to several reasons. With sustained disease control, patients would have no or fewer disease flares and require less resources and costs for disease management (e.g., clinic visits, examinations, and physiotherapy). Additionally, patients in remission may maintain better physical function and work productivity [3, 4], which could lead to reduced disease-related indirect costs.

While the clinical implications of achieving remission are well established, knowledge gaps exist regarding remission-associated economic value and potential savings to the healthcare system. Although a few studies have assessed healthcare costs and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) in patients with RA and different disease activity levels [i.e., remission, low disease activity (LDA), moderate/high disease activity (M/HDA)], heterogeneities exist between these studies regarding the country of interest, data sources, remission definition, and the approach of cost estimation, which render the evidence difficult to interpret and use to guide treatment decision-making. A comprehensive evaluation of the economic value of remission and whether it varies by the definition of remission is needed. Considering the differential cost savings associated with treatments with different efficacy profiles [5, 16], evidence regarding the economic benefits of remission could be used to better characterize the economic profile of RA treatments, thus informing treatment decision-making.

This review aimed to provide an overview of the clinical, humanistic, and economic value of clinical remission, with a focus on quantifying associated economic benefits. We summarized the significance of remission in clinical practice based on guideline recommendations, conducted a literature review, and synthesized evidence of clinical remission-associated healthcare savings from patient, payer, and societal perspectives.

Methods

First, existing clinical guidelines were identified to provide a summary of the current understanding and recommendations in clinical practice regarding achieving remission.

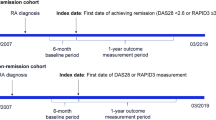

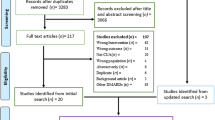

Second, a comprehensive literature review was conducted by searching the PubMed database (including MEDLINE and PubMed Central) to identify studies that reported economic outcomes by disease activity status in patients with RA, including direct medical costs, indirect costs, HRU, and work productivity. The search keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms listed in Table S1 in the supplementary material were used for the search strategy. On the basis of this search, 267 articles were identified, and 16 articles which reported economic outcomes (including direct medical costs, indirect costs, and HRU) by remission status were selected after abstract and full-text screening to be included in the summary (Fig. 1).

To enable a fair comparison between studies, costs were annualized and converted to 2020 euros, adjusting for inflation and currency exchange rates. For studies that did not directly report the cost among patients without remission but instead reported costs among LDA, MDA, or HDA, non-remission costs were calculated as a weighted average of costs in subgroups without remission (e.g., LDA and M/HDA) based on the sample sizes, when applicable.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Value of Remission in Clinical Practice

Application of Remission in Clinical Practice and Clinical Trials

A review of the current clinical guidelines indicates that the treat-to-target strategy is widely recommended in international and national clinical guidelines, including those endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK [4, 6, 7]. The approach was found to not only be more effective than usual care [6] but was also cost-effective [17,18,19]. According to the 2014 treat-to-target recommendations and clinical guidelines, the primary therapeutic target for RA should be a state of clinical remission, which is defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity [3, 6, 7]. If remission is not possible, LDA may be an alternative goal. Under the treat-to-target strategy, therapeutic interventions are used to abrogate the inflammation to reach and maintain explicitly specified and sequentially measured goals, usually assessed by a composite disease activity score [3]. Tight control, such as regular visits with disease activity assessments (e.g., every 1–6 months depending on the level of disease activity) and treatment adjustments at least every 3 months until the desired treatment target is reached, is applied to reach the goal [3]. In addition, besides assessing measures of disease activity, structural changes, functional impairment, and comorbidities should also be considered when making clinical decisions [3]. Once achieved, the desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease. Importantly, patients are more likely to achieve clinical remission when treated earlier in the course of RA [4, 20, 21]. Therefore, initiating an advanced treatment which offers a higher probability of achieving remission, immediately after conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) failure, may be preferred in order to maintain joint integrity and avoid disability in the long run [1].

Given the clinical value, remission measures are widely adopted as important outcomes in clinical trials to assess the efficacy of RA treatment [20, 22]. In the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines for RA, clinical remission has been suggested as an important measure to characterize the efficacy of the drug product and its utility in clinical practice [23].

Clinical and Humanistic Benefits of Achieving and Maintaining Remission

Achieving and maintaining clinical remission is associated with several clinical and humanistic benefits for patients. Patients in remission have better disease control and as a result improved radiographic outcomes, physical functioning (e.g., halt of joint damage and no development of disability), and lower mortality [24,25,26,27,28,29]. These improvements are observed with clinical remission irrespective of how early or late it is achieved [30].

The improved outcomes and physical functioning observed with remission also translate to a number of humanistic benefits. Achieving and maintaining remission improve patient QoL and other patient-reported outcomes. For instance, patients in remission have been shown to have higher scores in the EuroQoL 5D and Short Form 36 (SF-36) health surveys, which assess QoL based on different domains, like physical mobility, pain, and mental health [14, 24, 31]. Of note, when comparing patients with varying levels of disease activity (i.e., remission, LDA, and M/HDA), QoL assessment scores trend downwards as disease activity increases [14], demonstrating the considerable benefit of achieving remission on QoL measures. Domain-wise, patients in remission have better QoL in physical health, as indicated by less pain and fatigue [14, 31, 32], improved mental status (e.g., better sleep quality and less depression and anxiety) [31,32,33,34], and higher work productivity or capacity [14, 31, 35]. The aforementioned benefits of remission also exist in clinical and humanistic aspects when comparing to LDA, regardless of remission definition [13,14,15].

Economic Value of Remission

The reviewed studies considered various remission measures, adopted different methodologies to evaluate economic outcomes, and represented a broad range of geographic regions. Among the 16 studies included in the summary, there were ten studies from Europe (Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden) [14, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], five from North America (USA and Canada) [24, 45,46,47,48], and one from Asia (Japan) [49].

Different definitions of remission were used. The majority of the studies reported DAS28-based remission (i.e., DAS28 < 2.6; n = 13) [24, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46, 49], while a few studies also reported remission defined on the basis of SDAI (i.e., SDAI ≤ 3.3; n = 4) [14, 24, 46, 49], CDAI (i.e., CDAI ≤ 2.8; n = 5) [24, 46,47,48,49], and 28 joints-based Boolean criteria (n = 1) [46]. Direct medical costs were the most common economic outcomes evaluated (n = 13) [14, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], followed by HRU (n = 4) [24, 37, 38, 48], indirect costs (n = 3) [14, 40, 44], and work productivity (n = 2) [14, 49]. Different types of methodologies were adopted to evaluate the economic outcomes. For direct medical costs or HRU measures, the economic outcomes were either assessed using a claims/electronic health record (EHR) database or a patient/physician survey. For indirect costs or work productivity measures, the economic outcomes were estimated using patient-reported workday lost/disability. Of note, studies using claims/EHR databases to assess HRU/costs tended to report higher costs compared to those using patient/physical surveys in general.

Direct Medical Costs and HRU

Despite the variation in geographic focus, methodology, and remission definition, patients with remission consistently had lower direct medical costs or HRU compared to those without remission. In the 12 studies that reported direct costs by remission status (Table 1), patients with remission were reported to have a median annual medical cost of €2464 (range €821 [43] to €11,272 [47]) as compared to median costs of €4717 (range €1042 [43] to €16,879 [47]) among those without remission. The savings in direct costs between patients with remission and without remission ranged from 19% [46] to 52% [45]. Direct medical costs were assessed by disease activity levels (i.e., remission, LDA, and M/HDA) in nine articles (Table 2) [14, 36,37,38,39,40, 42, 45, 47]. Similarly, these studies showed cost savings associated with remission compared to both patients with LDA [median cost savings (percentage of saving) €285 (20%)] and patients with M/HDA [€3804 (51%)].

Despite the variation in reported direct medical costs across studies, similar cost components were considered, including outpatient/specialist visits, hospitalizations, medical exams/imaging/laboratory tests, surgery, physiotherapy, and orthosis. Some studies also included transportation, home care, and medications. Five studies evaluated the breakdown of direct medical costs by different components [36, 40, 43,44,45], with four indicating that physician and ambulatory care visits were the primary driver of the total medical costs [36, 40, 43, 44]. However, higher hospitalization rates may also drive the costs for patients without remission [36, 45]. Additionally, one study found that patients attaining sustained remission had lower orthopedic costs as compared to patients without sustained remission [46].

The economic benefits of remission on direct medical costs remain similar across different remission definitions. A study by Barnabe et al. concluded that a similar magnitude of cost savings was observed for remission defined on the basis of DAS28, SDAI, CDAI, and the most stringent Boolean criteria [46].

With regards to HRU, detailed HRU associated with RA by disease activity level was described in four studies [24, 37, 38, 48]. Boytsov et al. quantified and compared three HRU aspects across the three disease activity levels of remission, LDA, and M/HDA, and found that remission was associated with lower rates of hospitalizations (64% reduction), joint surgeries (53% reduction), and radiographs (24% reduction) compared to M/HDA [48]. In a separate study, Alemao et al. found that patients who achieved remission had significantly lower use of durable medical equipment (including walkers, wheelchairs, standers, and patient lifts) and lower hospitalization compared with patients who did not achieve remission [24]. A dose–response relationship was also observed between lower disease activity indices and lower durable medical equipment use or hospitalizations. Furthermore, in two studies, Beresniak et al. determined that patients in remission had substantially lower HRU in terms of physician visits, laboratory tests, radiographs, physiotherapy visits, and surgery compared to patients not in remission [37, 38].

Indirect Costs and Work Productivity Loss

A consistent benefit on indirect costs/work productivity loss was observed among patients with remission. The two studies evaluating indirect costs focused on different cost components [14, 40]. Miranda et al. assessed work productivity loss and reported a 75% reduction (€405) in indirect costs associated with remission (Table 1) [40]. In contrast, Radner et al. evaluated both work productivity loss and work disability (i.e., salary loss due to early retirement) and reported a 37% reduction (€5250) in annual indirect costs with achieving remission vs. not achieving it (Table 1) [14].

On the basis of the evidence, work disability may be the driving component of indirect costs. Radner et al. reported substantially higher overall indirect costs compared to Miranda et al., which is due to the inclusion of costs associated with work disability [14, 40]. Indeed, the former found that 34% of patients with RA with a mean age of 60 years were in early retirement due to RA [14]. Similarly, Boytsov et al. reported that 22% of patients with RA were retired early in the study sample, with a relatively lower percentage among patients with remission (17%) compared to patients without remission (19–25% depending on disease activity levels) [48]. Considering that patients in remission were able to delay or avoid early retirement, achieving remission early in the disease course and maintaining it can result in substantial cost savings.

Among patients who were currently employed, studies showed lower work productivity impairment in patients in remission, which is consistent with the findings of cost savings resulting from less work productivity loss. For instance, Radner et al. and Kim et al. reported a lower degree of RA-related impairment while working among patients with remission (8–12%), compared to LDA (21–27%) and M/HDA (30–46%) [14, 49]. A lower percentage of absenteeism was also seen among patients with remission (1%) compared to those with LDA (3%) or M/HDA (4%) [49].

Importantly, a large proportion of patients with RA also require care from relatives and friends with various issues, including household activities (cleaning, cooking, washing, etc.), personal care (dressing, eating, bathing, etc.), and other activities (gardening, shopping, etc.) [50]. While treating patients to remission may also have a positive economic impact by reducing the burden of informal care, not enough evidence has been provided in the literature.

In summary, this review has shown that remission was associated with lower direct and indirect costs and HRU compared with other disease activity levels. Major contributors to direct healthcare costs were physician visits, ambulatory care visits, and hospitalization. Of note, the time span of cost assessment in the studies included in this review ranged from 6 months [36,37,38,39, 41, 42] to 24 months [43]. Future studies with expanded data collection periods are needed to evaluate how remission impacts healthcare costs in the long term.

Discussion

In clinical practice, not all patients receiving RA treatment may be able to achieve remission, and the probability of attaining remission may depend on the application of treat-to-target strategy, type of therapy, and patient characteristics [20]. Innovative treatments that have improved efficacy profiles are usually associated with higher treatment costs [51]. However, these treatments may also offer a higher probability for patients to achieve and maintain clinical remission or LDA, especially if used early in the treatment sequence, potentially resulting in savings in direct medical costs and indirect costs. As such, savings in direct and indirect costs by disease activity status should be considered when quantifying the cost profile of RA treatments, particularly novel treatments with high remission rates. For example, JAK inhibitors are a new class of RA treatments that have favorable efficacy profiles among patients who have inadequate response to csDMARDs, with 24-week remission rates of up to 43% compared to 11% for csDMARDs in a meta-analysis of clinical trials [5]. Although JAK inhibitors have higher treatment costs (approximately $20,000 to $45,000 per year) than csDMARDs (e.g., methotrexate has an annual cost of $796), they may not only allow more patients to achieve better disease control but may also result in direct and indirect cost savings [52]. Thus, the cost-effectiveness and economic benefits of novel RA treatments, such as JAK inhibitors, would be underestimated if treatment costs alone are considered in economic evaluations.

Including the direct and indirect costs related to different disease activity statuses would more accurately estimate the economic profile of RA treatments. However, very few studies have considered these cost savings due to remission when performing the economic evaluations of RA treatments [53,54,55]. The cost benefit may be tailored for the patient, payer, or societal perspective. These insights can then be used to guide treatment selection for clinicians and payers.

Conclusion

Clinical remission is an important outcome in RA management and has wide applications in both clinical practice and regulatory approval of new therapies. Achieving clinical remission could promote better disease control and is associated with substantial economic benefits. On the basis of the literature review, patients with RA and clinical remission were found to have 19–52% savings in direct medical costs and 37–75% savings in indirect costs. Therefore, the economic value of remission should also be an important element to consider when performing economic analyses of different RA therapies to inform treatment and reimbursement decisions.

References

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360–72.

Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Pincus T, et al. Work disability remains a major problem in rheumatoid arthritis in the 2000s: data from 32 countries in the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(2):R42.

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3–15.

Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–77.

Pope J, Sawant R, Tundia N, et al. Comparative efficacy of JAK inhibitors for moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):2356–72.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management, pp. 1–32 (2018).

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(1):1–25.

Canhao H, Rodrigues AM, Gregorio MJ, et al. Common evaluations of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis reach discordant classifications across different populations. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:40.

Fransen J, van Riel PL. The Disease Activity Score and the EULAR response criteria. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(4):745–57.

Gul HL, Eugenio G, Rabin T, et al. Defining remission in rheumatoid arthritis: does it matter to the patient? A comparison of multi-dimensional remission criteria and patient reported outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(3):613–21.

Vander Cruyssen B, Van Looy S, Wyns B, et al. DAS28 best reflects the physician’s clinical judgment of response to infliximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients: validation of the DAS28 score in patients under infliximab treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(5):R1063–71.

Orr CK, Najm A, Young F, et al. The utility and limitations of CRP, ESR and DAS28-CRP in appraising disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:185.

Klarenbeek NB, Koevoets R, van der Heijde DM, et al. Association with joint damage and physical functioning of nine composite indices and the 2011 ACR/EULAR remission criteria in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1815–21.

Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R56.

van Tuyl LH, Felson DT, Wells G, et al. Evidence for predictive validity of remission on long-term outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(1):108–17.

Ma K, Li L, Liu C, Zhou L, Zhou X. Efficacy and safety of various anti-rheumatic treatments for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2019;15(1):33–54.

Vermeer M, Kievit W, Kuper HH, et al. Treating to the target of remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is cost-effective: results of the DREAM registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:350.

Wailoo A, Hock ES, Stevenson M, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treat-to-target strategies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(71):1–258.

Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–9.

Ajeganova S, Huizinga T. Sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: latest evidence and clinical considerations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9(10):249–62.

Nagy G, van Vollenhoven RF. Sustained biologic-free and drug-free remission in rheumatoid arthritis, where are we now? Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:181.

Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):404–13.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry rheumatoid arthritis: developing drug products for treatment. In: Services USDoHaH, pp. 1–11 (2013).

Alemao E, Joo S, Kawabata H, et al. Effects of achieving target measures in rheumatoid arthritis on functional status, quality of life, and resource utilization: analysis of clinical practice data. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(3):308–17.

Gullick NJ, Ibrahim F, Scott IC, et al. Real world long-term impact of intensive treatment on disease activity, disability and health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:6.

Scire CA, Lunt M, Marshall T, Symmons DP, Verstappen SM. Early remission is associated with improved survival in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(9):1677–82.

Listing J, Kekow J, Manger B, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of disease activity, treatment with glucocorticoids, TNFalpha inhibitors and rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):415–21.

Radner H, Alasti F, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Physical function continues to improve when clinical remission is sustained in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:203.

Ruyssen-Witrand A, Guernec G, Nigon D, et al. Aiming for SDAI remission versus low disease activity at 1 year after inclusion in ESPOIR cohort is associated with better 3-year structural outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(9):1676–83.

Ajeganova S, van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JA, Burgers LE, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-free sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: an increasingly achievable outcome with subsidence of disease symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(5):867–73.

Ishida M, Kuroiwa Y, Yoshida E, et al. Residual symptoms and disease burden among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission or low disease activity: a systematic literature review. Mod Rheumatol. 2018;28(5):789–99.

Curtis JR, Shan Y, Harrold L, Zhang J, Greenberg JD, Reed GW. Patient perspectives on achieving treat-to-target goals: a critical examination of patient-reported outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(10):1707–12.

Kekow J, Moots R, Khandker R, Melin J, Freundlich B, Singh A. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and their association with clinical remission among patients with moderate-to-severe active early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(2):401–9.

Son CN, Choi G, Lee SY, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis, and its association with disease activity in a Korean population. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30(3):384–90.

Gronning K, Rodevand E, Steinsbekk A. Paid work is associated with improved health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(11):1317–22.

Beresniak A, Ariza-Ariza R, Garcia-Llorente JF, Ramirez-Arellano A, Dupont D. Modelling cost-effectiveness of biologic treatments based on disease activity scores for the management of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain. Int J Inflamm. 2011;2011:727634.

Beresniak A, Baerwald C, Zeidler H, et al. Cost-effectiveness simulation model of biologic strategies for treating to target rheumatoid arthritis in Germany. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(3):400–8.

Beresniak A, Gossec L, Goupille P, et al. Direct cost-modeling of rheumatoid arthritis according to disease activity categories in France. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(3):439–45.

Cimmino MA, Leardini G, Salaffi F, et al. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of biologic agents for the management of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in anti-TNF inadequate responders in Italy: a modelling approach. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(4):633–41.

Miranda LC, Santos H, Ferreira J, et al. Finding Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact on Life (FRAIL Study): economic burden. Acta Reumatol Port. 2012;37(2):134–42.

Neubauer AS, Minartz C, Herrmann KH, Baerwald CGO. Cost-effectiveness of early treatment of ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis patients with abatacept. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(3):448–54.

Puolakka K, Blafield H, Kauppi M, et al. Cost-effectiveness modelling of sequential biologic strategies for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in Finland. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:38–43.

Ten Klooster PM, Oude Voshaar MAH, Fakhouri W, de la Torre I, Nicolay C, van de Laar M. Long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early rheumatoid arthritis patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(10):2727–36.

Hallert E, Husberg M, Skogh T. 28-Joint count disease activity score at 3 months after diagnosis of early rheumatoid arthritis is strongly associated with direct and indirect costs over the following 4 years: the Swedish TIRA project. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(7):1259–67.

Barnabe C, Thanh NX, Ohinmaa A, et al. Healthcare service utilisation costs are reduced when rheumatoid arthritis patients achieve sustained remission. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1664–8.

Barnabe C, Thanh NX, Ohinmaa A, et al. Effect of remission definition on healthcare cost savings estimates for patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic therapies. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(8):1600–6.

Curtis JR, Chen L, Greenberg JD, et al. The clinical status and economic savings associated with remission among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: leveraging linked registry and claims data for synergistic insights. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(3):310–9.

Boytsov N, Harrold LR, Mason MA, et al. Increased healthcare resource utilization in higher disease activity levels in initiators of TNF inhibitors among US rheumatoid arthritis patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(12):1959–67.

Kim D, Kaneko Y, Takeuchi T. Importance of obtaining remission for work productivity and activity of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(8):1112–7.

Husberg M, Davidson T, Hallert E. Non-medical costs during the first year after diagnosis in two cohorts of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis, enrolled 10 years apart. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(3):499–506.

Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Chen R, Lin GA, Tseng CW. Coverage for high-cost specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis in Medicare Part D. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1474–80.

Harrington R, Al Nokhatha SA, Conway R. JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: an evidence-based review on the emerging clinical data. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:519.

Foo J, Morel C, Bergman M, et al. Cost per response for abatacept versus adalimumab in patients with seropositive, erosive early rheumatoid arthritis in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(9):1621–30.

Park SH, Han X, Lobo F, Nanji S, Patel D. A cost per responder model for abatacept versus adalimumab among rheumatoid arthritis patients with seropositivity. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:589–94.

Weijers L, Baerwald C, Mennini FS, et al. Cost per response for abatacept versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis by ACPA subgroups in Germany, Italy, Spain, US and Canada. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(7):1111–23.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Financial support for the study (including Rapid Service Fee and Open Access fee) was provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in interpretation of data, review, and approval of the presentation. All authors contributed to development of the presentation and maintained control over final content.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Christine Tam, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., and funded by AbbVie, Inc. The authors would like to thank Yan Chen, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., for assistance with analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Cynthia Z. Qi, Aozhou Wu, and Keith A. Betts. All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Andrew J. Ostor has been a member of advisory boards and consultant, and undertaken clinical trials for AbbVie, BMS, Roche, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Gilead, and Paradigm. Keith A. Betts and Aozhou Wu are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consulting fees from the sponsor. Cynthia Z. Qi was a former employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consulting fees from the sponsor. Orsolya Nagy is an employee of AbbVie, Inc., and holds stock/options. Ruta Sawant was a former employee of AbbVie, Inc., and held stock/options, and is a current employee of Sage Therapeutics.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ostor, A.J., Sawant, R., Qi, C.Z. et al. Value of Remission in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Targeted Review. Adv Ther 39, 75–93 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01946-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01946-w