Abstract

Introduction

A vast increase in knowledge of numerous aspects of malignant salivary gland tumours has emerged during the last decade and, for several reasons, this has not been the case in benign epithelial salivary gland tumours. We have performed a literature review to investigate whether an accurate histological diagnosis of the 11 different types of benign epithelial salivary gland tumours is correlated to any differences in their clinical behaviour.

Methods

A search was performed for histological classifications, recurrence rates and risks for malignant transformation, treatment modalities, and prognosis of these tumours. The search was performed primarily through PubMed, Google Scholar, and all versions of WHO classifications since 1972, as well as numerous textbooks on salivary gland tumours/head and neck/pathology/oncology. A large number of archival salivary tumours were also reviewed histologically.

Results

Pleomorphic adenomas carry a considerable risk (5–15%) for malignant transformation but, albeit to a much lesser degree, so do basal cell adenomas and Warthin tumours, while the other eight types virtually never develop into malignancy. Pleomorphic adenoma has a rather high risk for recurrence while recurrence occurs only occasionally in sialadenoma papilliferum, oncocytoma, canalicular adenoma, myoepithelioma and the membranous type of basal cell adenoma. Papillomas, lymphadenoma, sebaceous adenoma, cystadenoma, basal cell adenoma (solid, trabecular and tubular subtypes) very rarely, if ever, recur.

Conclusions

A correct histopathological diagnosis of these tumours is necessary due to (1) preventing confusion with malignant salivary gland tumours; (2) only one (pleomorphic adenoma) has a considerable risk for malignant transformation, but all four histological types of basal cell adenoma can occasionally develop into malignancy, as does Warthin tumour; (3) sialadenoma papilliferum, oncocytoma, canalicular adenoma, myoepithelioma and Warthin tumour only occasionally recur; while (4) intraductal and inverted papilloma, lymphadenoma, sebaceous adenoma, cystadenoma, basal cell adenoma (apart from the membranous type) virtually never recur. No biomarker was found to be relevant for predicting recurrence or potential malignant development. Guidelines for appropriate treatment strategies are given.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An impressive increase in knowledge of the genetics, pathogenesis, diagnostic possibilities, clinical behavior, treatment modalities and prognosis of malignant salivary tumours has emerged during the last decade. A similar development has not happened with regards to benign salivary neoplasms, in despite the fact that a few of these are precursors to the malignant variants. The current 4th World Health Organization (WHO) classification of 2017 defines 11 different types of benign epithelial salivary tumours (some of them with subclassifications), 4 non-neoplastic epithelial lesions (1 of which future studies possibly may give evidence that it may be a neoplasm–sclerosing polycystic adenosis), 3 benign soft tissue lesions/tumours, and 22 carcinomas [1]. This is to be compared to the 1st WHO edition of 1972 that comprised just two adenomas (pleomorphic and monomorphic adenoma), two tumours (acinic cell tumour ad mucoepidermoid tumour) and five carcinomas [adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, epidermoid carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma and carcinoma in pleomorphic adenoma (PA)] [2]. A modified classification was proposed by Seifert et al. in 1990 [3] that led to the publication of the 2nd WHO classification in 1991 by which time the two recognisable benign tumour entities had risen to nine (two of which had subclassifications) [4]. With the continuous increase of knowledge, and a wider use of immunohistochemistry and molecular techniques, the separate entities have been better characterized and more widely accepted. Salivary gland tumours were included in the 3rd and 4th editions of WHO classifications of head and neck tumours (2005 and 2017, respectively) instead of being published in separate books [1, 5]. The histological identification of PA, Warthin tumour (WT) and, to a certain extent myoepithelioma (MYO), is usually relatively straightforward, but the classification of some of the other eight benign tumours can on occasion be rather difficult, primarily due to their rareness in a routine pathology laboratory set-up. Many may perhaps agree with Zarbo et al. in their statement related to less common benign salivary gland tumours “To wit, we believe it does not matter what these tumours are called as long as they are recognized and designated benign and the adequacy of excision is noted” [6]. However, it appears that some of the benign salivary gland tumours do have a tendency to recur, others have a very low tendency, while yet some others do not recur at all. A few are known to develop into malignant neoplasms, while in others malignant transformation is extremely rare, or has not yet even been reported. Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate via a search in the medical literature, whether the study of any biomarker and a correct histological subclassification would detect the risk for recurrence and/or potential malignant transformation for the different benign tumours. If so, the individual patient should more often benefit from receiving the most appropriate treatment as well as be given a correct evidence-based prognosis.

Methods

A thorough medical literature search has been performed, primarily PubMed, Google Scholar, numerous text books on head and neck pathology/salivary gland pathology/surgery/oncology, and the different editions of WHO classifications of salivary gland tumours. Each benign entity as defined by the 2017 WHO classification is listed in Table 1.

We describe here the histological characteristics of the 11 different types of benign epithelial salivary tumours and, for each entity, have studied the recurrence and malignant transformation potential, and the presence of any predictive factor.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The studies involved fully complied with the ethical standard of the hospitals involved and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. No informed consent from patients was required due to this being a retrospective study of archival histological material with de-identified data.

Results

The incidence and anatomical site of the tumours are outlined in Tables 2 [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and 3 [7,8,9,10, 14, 15]. The data have been collected from a few large series from different parts of the world which show wide variations between them. Totals of 2280 cases are reported in Table 2 and 1847 in Table 3. The latter compilation contains some cases also present in Table 2, but where the exact anatomical location was not given, hence a total of 2280 benign salivary gland tumours. These studies primarily comprise intraoral tumours, and the compiled data will only serve as a rough guideline. Intraoral tumours indicate oral tumours but also in some series include major salivary gland tumours affecting the oral cavity (submandibular, parotid and sublingual). However, benign tumours in, e.g., trachea, larynx, etc. are not included. For example, approximately 80% of basal cell adenomas (BCAs) occur in major salivary glands and in studies comprising only intraoral tumours the true relative frequency of BCAs in comparison with other adenomas will of course not be correctly reflected. These studies clearly indicate that adenomas, other than PA, WT, canalicular adenoma, and BCAs, are all quite rare. An accurate estimate of the incidence of each tumour entity is extremely difficult to obtain as geographical and racial differences exist, as well as changes in nomenclature over the years. Further, several of the larger studies only comprise intraoral or only major salivary gland tumours, while some include both major and minor salivary gland tumours. The criteria to differentiate between PA and myoepithelioma (i.e., presence of ducts, few ducts or no ducts) may differ between pathologists. Hence, an absolute correct compilation and estimation of incidences is not possible and has to be considered when reading the data given in Tables 2 and 3. For example, in a non-Asian population, canalicular adenoma is the most common adenoma of the 7 “rare” benign tumours, with an incidence similar to myoepithelioma, some 5–12%, of all benign tumours [7,8,9]. Reports from China are in sharp contrast, and the study by Wang and associates did not report a single case of canalicular adenoma amongst 737 cases of intraoral minor salivary gland tumours [10].

One very good effort at establishing the true incidence of benign salivary gland tumours was carried out by Bradley and McGurk, examining the unified computerised pathology records of two teaching hospitals covering a fixed population in the United Kingdom over two 10-year periods [13].

In the 2005 WHO classification, sialolipoma and keratocystoma were mentioned, but not as separate entities, and, due to lack of further substantial evidence since 2005, keratocystoma has been omitted entirely from the 2017 edition. Sialolipoma, however, is included as a separate entity, but as a soft tissue tumour rather than an epithelial tumour.

Lymphadenoma

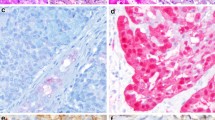

Lymphadenoma (LA) is a rare tumour with no sex predilection and mostly affecting adults aged > 30 years. The first report is attributed to McGavran and associates in 1960 [16]. Lui et al. reported 10 new cases in 2014, and at that time fewer than 110 cases had been reported in the English literature [17]. Thereafter, only a few case reports are available. LA is histologically characterised as being a circumscribed, often encapsulated, tumour consisting of benign basal and squamous cells, and can possibly be regarded as a BCA or cystadenoma accompanied by dense lymphoid tissue. The solid epithelial islands and trabeculae are basaloid cells while the cysts or gland-lining cells are ductal. The lymphoid component can be with or without lymphoid follicles. There are histologically two types of LA, the non-sebaceous adenoma with epithelial cell nests accompanied by often a prominent lymphoid stroma (Fig. 1a), and a sebaceous variant. In the sebaceous type, the peripheral (basaloid) epithelial cells are arranged in nests with partial sebaceous differentiation. The sebaceous type is more common and accounts for approximately two-thirds of LA cases. The parotid gland is the most common site for all lymphadenomas (> 80%).

a Lymphadenoma, non-sebaceous type. In a few of the epithelial cell nests, a central ductal structure is present. b Sebaceous adenoma with solid nests of sebaceous cells (a, b adapted from Hellquist and Skalova [25]). c Well-encapsulated (arrow) oncocytoma consisting of rather large oncocytes. d Parotid nodular oncocytosis. Note the absence of capsules. e Cystadenoma where the cysts are separated by thin fibrous septa. There are smaller papillary intraluminal projections and the cysts are often filled with eosinophilic “proteinaceous debris”. f Palatal sialadenoma papilliferum with an exophytic mildly papillary surface epithelium and underlying cystic proliferation of salivary ducts. g Higher magnification of the ductal proliferation; note more columnar and taller cells and also thicker fibrous septa than in cystadenoma (e). h CK7 stain highlights the salivary ductal cells with some ducts opening up in the exophytic CK7 negative surface epithelium

Lymphadenomas are cured by complete excision, and recurrence does not seem to occur. Malignancy arising in sebaceous LA has been reported on exceedingly few occasions. In 2003, Croitoru and associates reported one case of LA with transition to a sebaceous carcinoma, and they state that only three cases had been reported [18]. However, with regards to the two previously reported cases, the authors concluded that the two cases of sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma had arisen from sebaceous glandular remnants in a lymph node and thus not necessarily from a pre-existing LA [19]. On the other hand, the study by Seethala et al. of 33 cases of LAs convincingly demonstrated one case of malignant transformation of a LA to a sebaceous carcinoma (and one case to a basal cell adenocarcinoma) [20]. Hence, the extreme rarity, and possibly also confusion between lymphadenocarcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma, is further emphasised by the fact that neither lymphadenocarcinoma nor sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma are listed in the 2017 WHO classification as separate entities, in contrast to sebaceous adenocarcinoma [21]. Albeit a totally benign tumour, LA can be misdiagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma in a parotid lymph node or possibly even as a lymphoepithelial carcinoma. LA is virtually always well circumscribed, which distinguishes it from lymphoepithelial sialadenitis. A recent finding indicating an increased proportion of IgG4-positive plasma cells in LA may suggest that the pathogenesis involves an immune reaction similar to what may be the case with WT [22].

Sebaceous Adenoma

Sebaceous glands are common in the parotid gland (10–42% of glands), less frequently so in the submandibular glands (5–6% of glands), and very common in the oral mucosa which are found in up to 80% of individuals (Fordyce’s spots) [19, 23,24,25]. According to Gnepp, salivary gland sebaceous neoplasms can be classified into five groups: sebaceous adenoma (SA), and sebaceous lymphadenoma, sebaceous carcinoma, sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma, and sebaceous differentiation in other tumours [24]. Primary salivary gland sebaceoma has to our knowledge not been reported. The authors of the present study are not in full agreement in recognising sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma as an existing entity, a view apparently shared by the majority of the authors and editors of the 2017 WHO classification, as sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma is not listed as a separate tumour entity [1, 26].

SA is a very rare tumour, estimated to account for some 0.1% of salivary neoplasms and less than 0.5% of all salivary gland adenomas; in 2012, only about 30 cases had been reported [24]. Most cases (60%) arise in the major salivary glands with 5 out of 6 in the parotid gland. The buccal mucosa is the most common site when located in minor salivary glands [26]. SA is readily recognised as being a well-circumscribed to -encapsulated mass composed of solid nests of sebaceous cells embedded in a fibrous stroma (Fig. 1b). Squamous and oncocytic metaplasia, as well as foreign body giant cells, may be present. The sebaceous cells are immunoreactive for, e.g., epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), p63 and androgen receptors but also for more unusual antibodies like adipophilin and perilipin (rarely available in non-specialised laboratories). Sebaceoma that occurs in the skin can be a differential diagnosis, but no convincing case of salivary sebaceoma has to our knowledge been reported.

Sebaceous adenoma is not known to recur after adequate surgery [26]. Sebaceous carcinoma is recognised in the 2017 WHO classification and some 50 cases have been reported, for example as the malignant component in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA). Most, if not all, of the few cases reported appear to have arisen de novo and not from a pre-existing sebaceous adenoma [25, 27]. A recent study of ten new cases of sebaceous adenocarcinoma also supports that they arise de novo as none of the ten reported cases had arisen from a pre-existing sebaceous adenoma [28].

Oncocytoma

Oncocytoma (OC) is to be distinguished from diffuse and nodular oncocytosis and in the parotid possibly also from WT (Fig. 1c, d). A parotid fine needle aspirate, or core biopsy, comprising only of small groups of oncocytic cells can easily be appreciated as a WT but may well represent parotid oncocytosis [29]. Oncocytoma represents approximately 2% of all salivary gland neoplasms, occurs in elderly patients, and most cases are located in the parotid gland, though also in the submandibular gland and minor salivary glands [30, 31]. Oncocytoma is a well-circumscribed tumour and consists of large epithelial oncocytic cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm resulting from an accumulation of mitochondria, possibly due to mutations in mitochondrial DNA, as is the case in OC of other anatomical locations [32]. The cells thus stain with phosphotungsten acid haematoxylin and are strongly positive for CK7 and low-molecular weight cytokeratins. OCs are also strongly, but more patchily, positive for CK14, high-molecular weight cytokeratins and EMA. Oncocytes in OC are negative for CD10, in contrast to oncocytic renal cell carcinoma cells.

The basal cell population present in OC are positive for, e.g., p63 and CK5/6, which can be of help in distinguishing oncocytoma from acinic cell carcinoma [33]. The p63 positivity clearly discriminates oncocytic parotid cells from being metaplastic renal cell carcinoma cells. Hence, positive p63 and negative CD10 are together two strong biomarkers for oncocytoma, differentiating it from metastatic renal cell carcinoma, but are not predictive markers for recurrence or malignant transformation of oncocytoma.

Further, in contrast to acinic cell carcinoma with oncocytic cells, OC is negative for SOX10 and DOG1 [34]. DOG1 is an acinar and intercalated duct marker in salivary gland tissue and therefore not surprisingly negative in OCs [35]. A novel possibly promising immunohistochemical marker for oncocytic cells is the so-called BSND marker. The Barkitt gene (associated with, e.g., sudden deafness) encodes essential beta subunit for CLC chlorine channels, a protein involved in chloride transport, and is expressed in normal kidney and the inner ear, and also known as an immunohistochemical marker for chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma. BSND has recently been found to be expressed in the striated duct cells of normal salivary glands and has 100% positivity in WT and OC, while total negativity was demonstrated in 11 PAs, 7 adenoid cystic carcinomas, 6 acinic cell carcinomas, 6 mucoepidermoid carcinomas and 5 salivary duct carcinomas [36]. The BSND antibody does not discriminate between oncocytic renal tumour cells, WT or OC, but positivity excludes other salivary tumours with oncocytic cell participation, for example mucoepidermoid carcinoma and PA. The oncocytes are arranged as nests and sheets, trabeculae or ductal structures, and may contain cysts. The cells are often separated by a thin fibrovascular stroma. On very rare occasions, the major or entire part of the tumour may consist of clear cells (clear cell oncocytoma) [37], and in these cases several other differential diagnoses will become relevant.

Oncocytomas generally do not recur; however, they may be multifocal and any additional parotid OC not excised on the first occasion may incorrectly be appreciated as a recurrence. Oncocytic carcinoma does exist (see below), but the literature does not provide any substantial evidence that these exceedingly rare cases have arisen from a pre-existing OC [31, 38].

Cystadenoma

This tumour is not that rare in comparison with other salivary tumours, comprising at least 4% of benign salivary gland tumours [39, 40], and is primarily characterised by a multicystic nature. It is typically lined with proliferative, often papillary, and not infrequently oncocytic epithelium. The multicystic appearance is in contrast to unicystic tumours like, e.g., intraductal papilloma. Albeit both the 2005 and 2017 WHO editions mention cystadenoma to be unilocular in quite a high percentage of cases, these statements, however, refer to one study of a case report of two cases [41] and another older study from 1988 [42]. Most authors today would probably agree that cystadenoma is virtually always a multicystic neoplastic proliferation. The parotid gland is the most common site (45–50%), and the remaining cases are primarily found in the lip, buccal mucosa and palate. The common laryngeal multicystic non-neoplastic lesion, the mucous retention cyst, is sometimes misinterpreted as a cystadenoma.

Cystadenomas are slowly growing neoplasms and, when in the lip, they can clinically be appreciated as mucoceles. By 2015, only some 30 cases of the papillary variant of cystadenoma in minor salivary glands had been reported [40], while since then more than a dozen cases have been described [43,44,45,46].

Cystadenoma is a well-circumscribed, non-encapsulated tumour. The columnar or cuboidal epithelium often shows papillary projections into the lumen, is accompanied by basal cells, and mucous cells may be frequent. The mucinous cells are periodic acid Schiff (PAS)- and alcian blue-positive but negative for S100, p63, SMA and calponin. The papillary variants of cystadenomas are positive for p63 and other basal/myoepithelial cell markers. The lumina are often filled with an eosinophilic material consisting of inflammatory, squamous or foamy cells. The cysts are separated by a rather thin fibrous connective tissue that not infrequently contains seromucous glands. There is no atypia, no mitotic figures and no invasive growth pattern (Fig. 1e).

They have no tendency to recur but, on exceedingly rare occasions, cystadenocarcinoma arisen from a pre-existing cystadenoma has been reported [47, 48].

Sialadenoma Papilliferum

Papillary configuration is frequently seen in many salivary neoplasms, e.g., WT, oncocytoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (nowadays, polymorphous adenocarcinoma, PAC; [49]), papillary cystadenoma, etc. Ductal papillomas comprise a special group of adenomas with unique papillary features. In the 2017 WHO classification, the three different histologies have been separated into two entities, sialadenoma papilliferum and ductal papilloma (intraductal and inverted type) [50, 51]. Possibly, cystadenoma will eventually be included in this group of tumours, as the spectrum of intraductal papillary proliferations appears heterogenous. A recent amplicon-based massive parallel sequencing revealed an identical AKT1 p.Glu17Lys mutation in the three cases analysed, but no concurring mutations in other genes of the RAS or P13K pathway [52]. The three cases analysed by Agaimy and associates may perhaps not fit perfectly with the sialadenoma papilliferum spectrum and the AKT1 mutant tumours might represent a different entity.

Sialadenoma papilliferum (SP) is a non-encapsulated proliferation with a distinct and unusual histology comprising both an exophytic mucosal part and an inverted papillary intramucosal part of both salivary ducts and mucosal epithelium. The neoplastic part is the salivary ductal cells in the submucosa, which proliferate up into the surface epithelium, and the latter reacts with adjacent hyperplasia and papillomatosis (Fig. 1f). It is rare and comprises 0.4–1.2% of all salivary gland tumours. Approximately 80% of cases occur in the palate (particularly the hard palate), others in decreasing order in the buccal mucosa, upper lip, retromolar pad, and parotid gland, but cases have also been reported in the bronchus and nasopharynx [53, 54]. The peak age is in the 6th decade [55]. SP was first described by Abrams and Finck in 1969 [56] and presents clinically as a painless exophytic papillary mass, often misinterpreted clinically as squamous cell papilloma, warty dyskeratoma or verrucous carcinoma [57]. A literature review in 2007 by Mahajan et al. [58] found a total of only 47 reported cases, a number that has increased substantially following the 7 new cases reported by 2018 [55].

Histologically, there is a biphasic growth pattern of salivary duct epithelium into the squamous keratotic epithelium. The exophytic squamous proliferation is supported by fibrovascular cores extending up above the adjacent mucosa, and transition from the squamous epithelium to the ductal epithelium can be seen. The proliferating salivary duct epithelium consists of columnar and cuboidal cells frequently forming cysts that are CK7-positive which much of the adjacent papillary squamous epithelium is not, and the latter therefore likely represents a reactive squamous proliferation to the underlying neoplastic salivary ductal proliferation. The cells of the ductal epithelium tend to have rather large but uniform nuclei. These ductal cells are thus strongly positive to CK7 but also to S-100 (Fig. 1g, h). Occasionally, mucocytes can be seen in both the salivary and the squamous epithelium. The excretory ducts are thus the most likely site of origin.

Although recurrences are exceedingly rare, if they occur at all, a few cases of possible malignant transformation have been reported. In the case report of a mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising in a background of SP reported by Liu and associates. it is not entirely convincing that the SP had transformed into a mucoepidermoid carcinoma. It seems more likely that the SP was a bystander, but the possibility of a high-grade transformation of the SP cannot be totally excluded [59]. The second case described was not an invasive carcinoma but a carcinoma in situ of the exophytic squamous component [60]. The third case is possibly the most plausible one. Shimoda and associates described malignant transformation in a SP that may well have been a case of high-grade transformation, a genetic event not very well known at that time [61]. In the English world literature, we have thus only found one or two cases where malignant transformation of the SP may have occurred, and therefore we conclude that this tumour entity virtually has no malignant potential.

Ductal Papilloma: Intraductal Type

The intraductal papilloma (IDP) is a unicystic, circumscribed or encapsulated lesion consisting of a dilated salivary duct with papillary projections into the duct lumen. The majority of the approximately 30–40 cases of IDPs reported so far have been located in minor salivary glands; only 7 cases were reported in the parotid gland, including a few from the accessory parotid gland. The aetiology is unknown but a possible association with masticatory trauma has been proposed. They are thus most frequently located in the lower lip, floor of mouth, palate and tongue. The cells of the papillary ingrowth are of the same columnar/cuboidal cells that line the dilated duct, but there are also sometimes interspersed goblet-like cells. IDP has a delicate papillary network of cell-lined vascular fronds and the papillae partly fill the cystic cavity. Cytologic atypia and mitoses are virtually absent [62] (Fig. 2a, b). Papillary cystadenoma, on the other hand, is a multicystic lesion that has a variety of epithelial cell types, not only ductal cells (see “Cystadenoma”) [48, 63].

a An encapsulated intraductal papilloma in a minor salivary gland. b Higher magnification illustrating the delicate papillary network of cell-lined vascular fronds with the occasional goblet cell; atypia and mitoses are absent (a, b by courtesy of Dr Guy Betts, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, UK). c Non-encapsulated inverted papilloma with an endophytic growth pattern. The cells have an epidermoid and basal cell appearance and the tumour frequently contain smaller cysts. Inset Another example of inverted papilloma. d Canalicular adenoma of the upper lip with strands of single layered cells of one cell type and with the hallmark of a very paucicellular and vascular stroma; morules, i.e., squamous balls, may be present, either free in the lumen or attached (arrow). Inset Positive S100 staining, an enigmatic characteristic of canalicular adenoma. e Basal cell adenoma, primarily trabecular type, with anastomosing strands and cords of ductal and basaloid cells. Palisading of nuclei in the outer cells of the cords. f CK7 stain highlights the two cellular components of BCA (in contrast to only one in canalicular adenoma) with positive inner ductal cells and outer CK7 negative myoepithelial/basal cells

In contrast to its counterpart in the breast [64], salivary IDP has no tendency to recur and malignant transformations are virtually unheard of, apart from a papillary adenocarcinoma possibly arising from one parotid intraductal papilloma [65].

Ductal Papilloma: Inverted Type

Inverted ductal papilloma is more common than intraductal type ductal papilloma, and is a well-known tumour entity arising in many sites other than salivary glands, e.g., nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and urinary bladder. The first report in the salivary glands was published in 1981 by Batsakis et al., describing an epidermoid papillary adenoma [66], and the following year, the tumour was termed inverted ductal papilloma by White and associates [67], a terminology later embraced by Batsakis as well as by the 2005 and 2017 WHO classifications [1, 62, 68]. The study by Brannon and associates in 2001 revealed 33 reported cases up to that date [69], a number that today has increased to well over 50 cases [70]. Virtually all reported tumours have been located in minor salivary glands [62], and, on exceedingly rare occasions, possibly in the major salivary glands [50].

Inverted ductal papilloma is a circumscribed, well-demarcated but unencapsulated, endophytic papillary proliferation. It arises at the junction of a salivary gland and the oral mucosa and the papilloma are frequently continuous with the overlying mucosal epithelium. The lesions are often nodular but may also be cystic. The proliferating epithelial cells have the appearance of epidermoid and basal cells forming broad papillary projections. There may be some columnar cells as well as mucous cells and microcysts. The cells are cytologically bland and there are few mitotic figures (Fig. 2c). The endophytic, intraductal component of some oral condyloma acuminatum histologically has the appearance of inverted ductal papilloma. The surface keratinisation and the presence of koilocytes typical of condyloma acuminatum are, however, not seen in the intraductal component [71]. Some reports have indicated the presence of HPV 6/11 in inverted ductal papilloma as well as in inverted ductal papilloma associated with condyloma acuminatum [72, 73]. In contrast, a study from 2013 revealed no presence of HPV viral DNA in an inverted ductal papilloma of the lip, but the patient had a previous history of trauma [74].

The histological features are thus very similar to those of sinonasal inverted papilloma but, in contrast to the sinonasal papilloma, recurrence and/or malignant transformation is not known to occur.

Canalicular Adenoma

Historically canalicular adenoma was considered a variant of BCA which was recognised as a separate entity for the first time in the 1991 WHO classification [4]. This is a peculiar and histologically a very readily recognisable benign salivary gland tumour. The vast majority, 60–80%, if not more, occur in the upper lip, the rest primarily in the buccal mucosa and in the hard palate, and at other sites, but virtually never in the major salivary glands [75]. CA occurs almost exclusively in patients over 50 years of age, is commonly multifocal, well circumscribed and rarely larger than 2 cm. In some studies from Western countries, they represent 7–12% of all benign salivary tumours, making it the 3rd or 4th most common benign epithelial salivary tumour [7,8,9, 76, 77]. In sharp contrast, in a large study from China comprised of 737 intraoral minor salivary gland tumours, not a single case of canalicular adenoma was reported [10]. The tumour is composed of columnar and cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming bilayered strands, thus consisting of only one cell type, diagnostically S-100 positive (Fig. 2d). These anastomosing strands of cells are separated by a loose, paucicellular, highly vascular stroma. This stroma is characteristically alcian blue- and PAS-positive (2.5) and CD15-positive.

There are also morules present, i.e., squamous balls, that may lie free in the lumen or be attached (Fig. 2d). Microliths and tyrosine crystals may be present. The tumour cells are positive for S-100 and cytokeratins but negative for CEA and display a variable reactivity for EMA. The total lack of duct-surrounding cells, cells that usually are immunopositive for p63, calponin, SMA, etc., readily discriminates canalicular adenoma from, e.g., BCA (the latter always consists of two cell types with a different immunophenotype, e.g., CK and p63) or myoepithelioma of a trabecular type. CAs are in the vast majority of cases readily recognised on H&E-stained slides and immunohistochemistry or special stains are generally not needed, particularly not when located in the lip. The main differential diagnosis that could possibly be considered are PAC, adenoid cystic carcinoma and BCA. From the large series (67 cases) reported by Thompson and associates, it appears evident that it is almost impossible to distinguish between recurrence or persistence of multifocality (9 patients had multifocal tumours, 5 of whom had additional tumours removed up to decades later). No malignant transformation was observed [75]. A very rare case of a total of nine separate nodules in the upper lip was reported, where one nodule was a polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma PLGA (recently PAC) synchronous with eight canalicular adenomas [78]. In a review of 430 cases of CA, recurrence was reported in 3% of cases [77]. Hence, CA can be considered a tumour that very rarely recurs, with malignant transformations yet to be reported.

Basal Cell Adenoma

BCA consists of basaloid cells, with occasional inner ductal epithelial cells, arranged in four different cellular growth patterns, described as solid, trabecular, tubular (tubulo-trabecular) and membranous. BCA accounts for 1.8–5% of all salivary gland tumours. It is predominantly a tumour of major salivary glands with approximately 75–80% of cases found in the parotid glands and at least 5% in the submandibular glands. It tends to occur in elderly patients with a peak in the seventh decade and with a slight female predilection, and hence in a rather older age group than PA [79]. The upper lip is the most common minor salivary gland origin. In a study of 6982 minor salivary gland tumours in a Chinese population, BCA was extremely rare [11], but less so in a Western population [80].

At least four growth patterns are recognised and often combinations thereof may be seen in the same tumour. The solid type of BCA sometimes resembles a nodular or solid subtype of basal cell carcinoma of the skin. There are solid nests of crowded basaloid tumour cells surrounded by a palisading outer layer of columnar or cuboidal cells. Squamous metaplasia can occasionally be seen in BCA, hence another feature in common with skin basal cell carcinoma. The trabecular type of BCA has basaloid cells arranged in strands and cords of varying thickness, although often rather thin and narrow. These cords are separated by a fibrous sometimes cellular stroma. In some areas, the stroma may be vascular and with thin cords and the features may mimic a canalicular adenoma. The tubular type of BCA has strands of basaloid cells with numerous small duct lumina lined by cuboidal, often eosinophilic, cells. The lumina often contain a PAS-positive material. Some tubular BCAs can be oncocytic. Most often, BCAs are not purely trabecular or tubular but contain variable proportions of both elements and are referred to as tubulo-trabecular BCA. The inner ductal cells typically stain for CK7 but the outer myoepithelial cells are positive for more typical myoepithelial marker such as SMA. p63 and high-molecular weight cytokeratins [81, 82] (Fig. 2e, f). The trabecular and tubular types are more common than the solid and membranous types, but often the different patterns are coexistent. Usually, one growth pattern predominates and all four types of BCA can be cystic, and all BCAs are well circumscribed or encapsulated. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, PAC and even canalicular adenoma can occasionally constitute a differential diagnosis. The identification of a capsule, no invasive growth pattern, no or very little atypia present, and a low proliferation index as measured by Ki-67, will always strongly favour a BCA.

The membranous type of BCA (dermal anlage type, dermal analogue tumour) was first reported by Drut in 1974 when describing a parotid tumour as a “cutaneous type of cylindroma” and was later termed “dermal analogue tumour” by Batsakis and Brannon in 1981, but in the 2nd WHO classification it is referred to as membranous type BCA [4, 83, 84]. Membranous BCA is characterised by multiple nests or islands of basaloid epithelial cells having palisading of peripheral cells and a excessive hyaline basal membrane; hence, there are thick bands of hyaline material surrounding the epithelial islands. Both sebaceous and epidermoid differentiation can be seen in the cell islands. Membranous BCAs are multinodular often multicentric and rarely encapsulated, and therefore an infiltrative growth pattern is imparted to this type of BCA. The membranous BCA resembles the dermal cylindroma and not infrequently coexists with tumours of the skin, e.g., eccrine cylindroma or trichoepithelioma of the scalp (turban tumour) as a part of Brooke–Spiegler syndrome. Immunohistochemically, all BCAs will exhibit ductal and some degree of myoepithelial differentiation and are positive for keratin markers such as CK7 and others, but also, in contrast to canalicular adenoma, variably positive for myoepithelial markers (SMA, vimentin, p63, S-100, etc.). It is worth recalling that both basal cells and myoepithelial cells stain positive for p63 [6, 85, 86].

The literature gives the histological classification for the four types described above no clinical value apart from separating membranous BCA from the other types. The membranous type of BCA may have a recurrence rate of as much as 25%, while the other types can be regarded as non-recurrent tumours [87, 88]. On rare occasions, malignancy may develop from a BCA (any subtype) and usually as a basal cell adenocarcinoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma, but salivary duct carcinoma and intracapsular adenocarcinoma NOS and intracapsular myoepithelial carcinoma have also been reported. In one series, malignant transformation occurred in as much as 4.3% [89, 90].

Warthin Tumour (WT)

WT is a benign well-encapsulated parotid tumour usually occurring in the caudal pole and is the second most common benign salivary gland tumour. In a series of 239 benign parotid tumours, 55.2% were PAs while WTs constituted 36.4% [13, 91]. It consists of an oncocytic epithelial cell component arranged in double layers which develop cysts and papillary projections. There is characteristically a stroma component consisting of a variable amount of lymphoid tissue. WT was first reported in 1895 [92] and was recognised in 1910 as separate diagnostic entity called papillary ‘cystadenoma in lymphatic glands’ [92, 93]. In 1929, Warthin described the reported cases of this tumour up to that date and thus it later became known as the Warthin tumour [94]. WTs rather frequently arise in intra- and periparotid lymph nodes, and, in two series of 333 and 176 cases of WTs, 9 (2.7%) and 14 (8%) were located in parotid lymph nodes, respectively [95,96,97]. WT is almost exclusively found in the parotid but a few cases in the submandibular gland, palate, buccal mucosa, lips, larynx and nasopharynx have been reported [90, 98].

WT is the most common synchronous multiple salivary gland tumour followed by PA [13, 99,100,101]. Multiple salivary gland tumours should be distinguished from tumours with biphasic differentiation and from so-called hybrid tumours. Synchronous benign and malignant salivary gland tumours are very rare but WT and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are the most common combination [102]. In a study of 341 patients with parotid tumours, synchronous multiple tumours were found in 14 cases, 9 of which were WTs [103]. In another series of 78 WTs, multiple tumours were reported in as many as 20% of cases, and a third of these cases were also bilateral [104]. Bilateral WTs were found in 10% of cases in a study of 73 patients [105]. The high tendency for multiple tumours has to be considered when a second tumour arises, i.e., is that a true recurrence or is it a tumour left behind at the first surgical exploration? In a cross-sectional study of 628 parotid tumours, there were 150 cases of WT (24%), and in approximately 10% of cases the tumours were multicentric. In cases of solitary WT, the recurrence rate was 0% and while it was 10% in the multicentric tumour group [106]. Multifocality and bilaterality are especially important in heavy smokers and every effort should be made to promote smoking cessation in these patients.

Malignant transformation of WTs is rare. Carcinoma in WT does not necessarily imply malignant transformation of the epithelial oncocytic component, as synchronous benign and malignant salivary gland tumours do exist, albeit rarely, and WT and mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common observed combination. In 1997, Seifert described five malignancies which had arisen in WTs, and the histological criteria for malignant transformation in a WT should include a continuous transition zone from the benign double-layered oncocytic epithelium into an invasive epithelial malignancy [107]. Based on Seifert’s report and subsequent published cases, the literature contains only approximately 50 carcinoma cases, squamous cell carcinoma being the most common, but mucoepidermoid carcinoma, oncocytic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma have also been reported [108,109,110,111,112,113]. In some of the reported cases, WTs developing into mucoepidermoid carcinomas could represent WTs with extensive mucocyte metaplasia or pure Warthin-like variants of mucoepidermoid carcinoma and thus the figure given above of 50 cases is likely too high.

WTs, both in the parotid gland or neighbouring lymph nodes, may occasionally be associated with different lymphoproliferative disorders and some 20 cases have been reported, possibly several of which have been collision tumours. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas are most common [114,115,116], but a few cases of Hodgkin’s lymphoma have also been reported [117, 118]. A few cases of nodal peripheral T cell lymphoma [119] and MALT-type lymphoma [120] associated with WT have been described.

Myoepithelioma (MYO)

MYO is defined as a tumour composed of myoepithelial cells that exhibit spindle, epithelioid, plasmacytoid or clear cytoplasmic features. The tumour is made up of myoepithelial cells alone or with the addition of very small numbers of ductal structures. The cells are arranged in different patterns and grow in a mucoid, collagenous or vascular stroma. Myoepitheliomas were previously thought to lack the myxoid or chondroid stroma typical of PA, but such stromal changes are nowadays recognised to be present. MYO may hence be histologically very similar to PA, and the scarcity, or total lack, of duct-like structures may be the only distinguishing feature. They are encapsulated or at least well-circumscribed tumours and the majority arise in the parotid gland. The proportion of myoepitheliomas located in the parotid gland range from 40 to 90% in different reported studies series and of intraoral minor salivary glands, the palatal glands are most commonly affected. MYO may occasionally arise in the submandibular gland but only a dozen of cases have been reported in the English literature. Myoepithelioma are much less prone to recur than PA and recurrence appears to be strongly correlated with incomplete surgery [121].

Malignant transformation to myoepithelial carcinoma may occur but is exceedingly rare [122, 123]. The few reported cases of myoepithelial carcinoma appear to have arisen in two different settings; either de novo or in a recurrent PA, and thus only very rarely from a pre-existing MYO [124,125,126,127].

Pleomorphic Adenoma (PA)

Since its first description by Billroth in 1859, the terminology for this entity has veered between “mixed tumour”, complex adenoma and PA. In spite of that, it has a prominent mesenchymal-appearing “stromal” component, and is not a truly mixed neoplasm, i.e., it is derived from more than one germ layer. PA is of purely epithelial origin characterised by a dual cell population of neoplastic cells and ductal and myoepithelial (possibly also basal) cells where the “mesenchymal” part of a PA is the result of a metaplastic process of the neoplastic myoepithelial cells. PAs show a vast number of different microscopic patterns depending on the arrangement of the epithelial cells and how much and what type of stroma is present. The morphology of PA is well known to any pathologist, and it is beyond the scope of this article to describe and illustrate all the different oncocytic, osseous, sebaceous and lipomatous metaplasia, as well as pigmented variants of PA, and infarcted PA. The concepts of PA with atypical features, metastasizing PA, subclassification of CXPA into non-invasive (intracapsular, in situ), and minimally invasive (≤ 1.5 mm) and widely invasive CXPA, are of interest as the tumours belonging to the first two groups (in situ and minimal invasive) have an excellent prognosis and, apparently need no adjuvant treatment to radical surgery [128].

In the present study, our interest in PA is primarily focused on the fact that PA is by far the most common salivary gland neoplasm, and can also, in small biopsy specimens, mimic other salivary gland tumours and even be confused with malignant tumours. Other very important features for this study are the tendency of PA to recur, and not at least that overt malignancy develops in at least 5–15% of cases which makes CXPA the 4th or 5th most common malignant salivary gland tumour [129]. In Denmark, the rate of malignant transformation has been reported in 2% of cases [130]. PAs are generally slow-growing tumours often present for years before the patients seek medical advice. Most are located in the tail of the parotid gland and only 10% are present in the deep portion of the gland beneath the facial nerve and may then present as a parapharyngeal mass.

The treatment of PA is complete surgical excision which will constitute cure in a vast percentage of cases. The extension of the surgery in parotid gland tumours is controversial. Different surgical options co-exist nowadays, and the discussion between the more limited resections (extracapsular dissection) in front of more classical options (partial, superficial or total parotidectomy) is still very alive. Different schools favour one option or another depending on their experience, their skill and their tradition, but probably the surgery should be adapted to the size and the situation of the tumour [131, 132]. For PAs in minor salivary glands, or if not situated in the superficial parotid lobe, complete surgical excision is not always readily performed. PA is rarely multifocal and, with current management of parotid PA, the recurrence rate is estimated to be 2.9% [130].

As pointed out in recent reviews, the most important cause of recurrent PA is enucleation with rupture of the tumour capsule and incomplete tumour excision at operation. Incomplete pseudocapsule, extracapsular extension, pseudopodia of PA tissue, and satellite PA beyond the pseudocapsule are also likely linked to recurrent PA. Tumour spillage is clearly involved in recurrences. In a study of the outcome of parotid surgery in 182 cases, tumour disruption and spillage had an independent effect on recurrence: 26.9% recurrences in disruption and 80% in spillage [133, 134].

Malignant transformation (CXPA) usually occurs in recurrent PAs that have been present for long periods of time, and in some series as long as 23 years, while in other series 45% of tumours had, however, been present for less than 3 years [135, 136]. CXPA tends to present late in life, often in the 6th and 7th decades, which is a decade later than PA. CXPA most commonly arises in the parotid gland and only rarely in the submandibular gland [129, 137,138,139]. Virtually any salivary type carcinoma may develop, possibly with the exception of acinic cell carcinoma, and usually only one histological type is encountered. In an extensive literature review by Gnepp, he found 42 cases of carcinosarcoma and, in at least 11 of these cases, there was a previous history of PA [129]. Inadequate surgical procedures leading to multiple recurrences appear in most cases to be a prerequisite for malignant transformation but also for metastatic disease [140,141,142,143]. However, 83.6% of CXPA are de novo in Denmark, i.e. no previous operation for CXPA [130].

Discussion

The data collected from the literature indicate rather clear differences in clinical behaviour between the different benign epithelial salivary gland tumours—even when given adequate initial surgical treatment. PA is overwhelmingly the most common of all salivary neoplasms and, due to its high tendency for recurrence and malignant transformation, and with its broad histological spectrum, is the most important benign salivary tumour to diagnose correctly. In many decent-sized biopsy specimens, and core biopsies, even experienced pathologists can confuse PA with several of the other benign, and malignant, salivary neoplasms, e.g., epithelial–myoepithelial carcinomas, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (although PA does not have the typical nuclei of cribriform type of PAC) and some adenoid cystic carcinomas. The myoepithelial/basal outer cells of the duct-structures in PAs and other tumours may be spindle-shaped, epithelial or clear cell in appearance. In cases with a mucoid/myxoid stroma with typical stellate and epithelioid myoepithelial cells, the ductal-like cells are p63 negative and the myoepithelial cells p63 positive. Similarly, in this myxoid/mucoid variant, both cellular elements are positive for vimentin, S-100, and pancytokeratin, and many but not all of the myoepithelial cells are negative. Other keratin markers like pancytokeratin, CK 5/6, CK14 and CK8/18 similarly give a strong staining of the ductal cells but tend to stain the myoepithelial cells more weakly. The most reliable markers for both types of cellular elements in this type of PA are, hence, p63, CK5/6, CK8/18, vimentin and S-100. It may be emphasised that the p63 and p73 genes are members of the p53 family and in contrast to p53 play important roles in stem cell identity and cellular differentiation. Both are expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells, but it appears that p63 is a more specific marker of myoepithelial differentiation than p73. All isoforms of p63 are said to be expressed in normal salivary tissue, whereas PAs (as well as myoepitheliomas and BCAs) dominantly express the transactivation-incompetent truncated isoforms. Negative PLAG1 immunostaining will rather strongly support that the salivary tumour is not a PA, and positive PLAG1 staining does not necessarily indicate a PA, as it is present, for example, in some CXPA.

In some PAs, there are areas where the proliferating cells have a reticular (canalicular-like) growth pattern and may mimic a canalicular adenoma. Tumours with numerous myoepithelial cells of the plasmacytoid type are more commonly found in minor salivary gland PAs (and MYOs). The plasmacytoid tumours tend to be positive for vimentin, cytokeratin, S-100 and GFAP while negative for SMA and MSA. This is in contrast to tumours with predominantly spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells which tend to be positive for SMA and MSA, in addition to sharing the positivity for the other four markers. The staining patterns for SMA and MSA are in keeping with the relative absence of myogenous differentiation in the plasmacytoid cells. In biopsies from minor salivary gland tumours, caution is warranted not to confuse a PA with polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Recently, the E710D hotspot mutation in the PRKD1 gene has been shown to have a 100% specificity in separating PAC from PA and adenoid cystic carcinoma on fine needle aspiration (FNA) [144].

Vascular tumour invasion, particularly capsular vascular invasion, is a rare and well-known, but also a much debated, feature of PA. The biological significance is not known but the general concept is that this does not indicate malignancy. It may of course be related to the enigma of metastasizing PA. In a study by Skalova and associates, 22 cases of PA were demonstrated to have intravascular tumour deposits. In 7 of these patients, a FNA had previously been performed which possibly could be related to the intravascular tumour deposits. Tumour cells were found in both thin-walled and muscular thick-walled vessels [145]. PAs show a myriad of different histological appearances while myoepitheliomas are morphologically much more monotonous. MYOs are generally considerably more cellular, show less metaplastic phenomena, have very few ductal structures and small or no amounts of mucinous/myxoid/chondroid stroma. Some authors require a total absence of ductal elements for the classification of MYO. The immunophenotype will depend on which one(s) of the four main histological types of neoplastic myoepithelial cells (briefly described above) the tumour consists of. The significantly lower rate of recurrence and virtually no malignant potential merit their distinction as a separate entity and separation from PA. Caution also has to be taken in cases of cystic PA with squamous metaplasia so as not to be confused with low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

BCAs, other than perhaps the membranous type, may constitute a differential diagnosis. It is worth remembering that at least 80% of BCAs are located in major salivary glands and are thus relatively rare in minor salivary glands. They all have two cellular components, clearly expressed by immunohistochemistry, and they do not express PLAG1. The membranous type’s relatively high tendency for recurrence, and the potential for malignant transformation in all four types, are factors that demand their recognition and separation from other adenomas.

WT was for a long period of time regarded as not having any malignant potential, and to that extent some 20–30 years ago elderly patients with no symptoms, and no major cosmetic concerns, were offered the choice of surgery or leaving the lump as it was. Today, a sufficient number of cases of malignancy arising in WTs have been reported, and, combined with our knowledge of its great tendency for synchronous tumours, many cases likely do warrant a surgical intervention.

Intraductal papilloma, inverted papilloma, lymphadenoma, sebaceous adenoma, cystadenoma, sialadenoma papilliferum, oncocytoma, canalicular adenoma, and myoepithelioma are rare entities that can be diagnosed correctly with sufficient experience. However, their diagnosis currently carries few clinical implications with the exception that some of them have a remote tendency to recur, and may occasionally be confused with a malignant neoplasm. It is again emphasised that sialadenoma papilliferum is a non-encapsulated proliferation while intraductal and inverted intraductal papilloma are circumscribed. Sialadenoma papilliferum and intraductal papilloma consist primarily of ductal columnar and cuboidal cells while an inverted papilloma consists primarily of epidermoid-like (ductal) cells. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma may theoretically constitute a histological differential diagnosis in cases of sialadenoma papilliferum and inverted ductal papilloma, while, as in cases of intraductal papilloma being an unicystic tumour, cystadenoma should not be a realistic differential diagnosis.

Over the years, recurrent benign salivary tumours have mainly been blamed on inadequate surgical procedures or spillage from FNAs. Recent epigenetic studies on tumours and tumour-adjacent tissue in other organs [146,147,148], as well as ongoing studies on salivary gland tissue (unpublished data), may possibly reveal that other factors play a role and that the surgical technique is not always to be blamed for recurrences. The remaining tumour host organ tissue itself may have undergone genetic and/or epigenetic changes, although microscopically it looks normal. These changes could be responsible for stimulating the proliferation of a new tumour rather than the second tumour being a recurrence due to tumour tissue left behind after the first operation/or spillage.

Conclusion

Based on our findings of the histology and clinical behaviour of the different tumour entities, we emphasise the need for correct histological recognition of all benign salivary tumours, but particularly PA with all its histological variants, the different variants of BCA and WT. It may seem superfluous in the latter case, but a careful examination of any epithelial dysplasia or suggestions of lymphoproliferative disorder is necessary. The diagnosis of the other types of benign epithelial tumours will give guidance for the risk for recurrence, and careful histopathological diagnosis to avoid confusion with a malignant salivary gland tumour is, of course, a necessity (see Supplementary material).

References

El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. Tumours of salivary glands. In: WHO classification of head and neck tumours, 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 159–202.

Thackray AC, Sobin LH, editors. Histological typing of salivary gland tumours. Geneva: WHO; 1972.

Seifert G, Brocheriou C, Cardesa A, Eveson JW. WHO international histological classification of tumours. Tentative histological classification of salivary gland tumours. Pathol Res Pract. 1990;186:555–81.

Seifert G, Sobin LH, editors. Histological typing of salivary gland tumours. In: WHO international histological classification of tumours. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 1991.

Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Tumours of salivary glands. In: WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 209–81.

Zarbo RJ, Prasad AR, Regezi JA, Gown AM, Savera AT. Salivary gland basal cell and canalicular adenomas; immunohistochemical demonstration of myoepithelial cell participation and morphogenetic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:401–5.

Yih WY, Kratochvil FJ, Stewart JC. Intraoral minor salivary gland neoplasms: a review of 213 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:805–10.

Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of intra-oral minor salivary gland tumors: a study of 380 cases from northern California and comparison to reports from other parts of the world. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:207–14.

Jones AV, Craig GT, Speight PM, Franklin C. The range and demographics of salivary gland tumours diagnosed in a UK population. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:407–17.

Wang D, Li Y, He H, Liu L, Wu L, He Z. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumours in a Chinese population: a retrospective study on 737 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:94–100.

Tian Z, Li L, Wang L, Hu Y, Li J. Salivary gland neoplasms in oral and maxillofacial regions: a 23-year retrospective study of 6982 cases in an eastern Chinese population. Int J Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:235–42.

Lukšić I, Virag M, Manojlović S, Macan D. Salivary gland tumours: 25 years of experience from a single institution in Croatia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:e75–81.

Bradley PJ, McGurk M. Incidence of salivary gland neoplasms in a defined UK population. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:399–403.

Wang XD, Meng LJ, Hou TT, Zheng C, Huang SH. Frequency and distribution pattern of minor salivary gland tumors in a Northeastern Chinese population: a retrospective study of 485 patients. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2015;73:81–91.

Shen SY, Wang WH, Lian R, Pan GQ, Qian YM. Clinicopathologic analysis of 2736 salivary gland cases over a 11-year period in Southwest China. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138:746–9.

McGavran MH, Bauer WC, Ackerman LV. Sebaceous lymphadenoma of the parotid gland. Cancer. 1960;13:1185–7.

Liu G, He J, Zgang C, Fu S, He Y. Lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: report of 10 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1097–101.

Croitoru CM, Mooney JE, Luna MA. Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003;7:236–9.

Gnepp DR, Brannon R. Sebaceous neoplasms of salivary gland origin. Report of 21 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:2155–70.

Seethala RR, Thompson LD, Gnepp DR, Barnes EL, Skalova A, Montone K, et al. Lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 33 tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:26–35.

Gnepp DR, Assaad A, Ro JY. Sebaceous adenocarcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 178–9.

Kim J, Song JS, Roh JL, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY, et al. Increased immunoglobulin G4-positive plasma cells in lymphadenoma of the salivary gland: an immunohistochemical comparison among lymphoepithelial lesions. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018;26:420–4.

Gnepp DR. Sebaceous neoplasms of salivary gland origin: a review. Pathol Annu. 1983;1:71–102.

Gnepp DR. My journey into the world of salivary gland sebaceous neoplasms. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:101–10.

Hellquist H, Skalova A, editors. Other adenomas. In: Histopathology of the salivary glands. Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. p. 141–80.

Gnepp DR, Bell D, Hunt JL, Seethala RR. Sebaceous adenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 193–4.

Hellquist H, Skalova A, editors. Other carcinomas. In: Histopathology of the salivary glands. Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. p. 375–427.

Soares CD, Morais TML, Carlos R, Jorge J, de Almeida OP, de Carvalho MGF, et al. Sebaceous adenocarcinomas of the major salivary glands: a clinicopathological analysis of 10 cases. Histopathology. 2018;73:585–92.

Rooper LM, Onenerk M, Siddiqui MT, Faquin WC, Bishop JA, Ali SZ. Nodular oncocytic hyperplasia: can cytomorphology allow for the preoperative diagnosis of a nonneoplastic salivary disease? Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:627–34.

Thompson LD, Wenig BM, Ellis GL. Oncocytomas of the submandibular gland. A series of 22 cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1996;78:2281–7.

Katabi N, Assaad A. Oncocytoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 189–90.

Mayr JA, Meierhofer D, Zimmermann F, Feichtinger R, Kögler C, Ratschek M, et al. Loss of complex I due to mitochondrial DNA mutations in renal oncocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2270–5.

Weiler C, Reu S, Zengel P, Kirchner T, Ihrler S. Obligate basal cell component in salivary oncocytoma facilitates distinction from acinic cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:838–42.

Schmitt AC, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT. Expression of SOX10 in salivary gland oncocytic neoplasms: a review and a comparative analysis with other immunohistochemical markers. Acta Cytol. 2015;59:384–90.

Khurram SA, Speight PM. Characterisation of DOG-1 expression in salivary gland tumours and comparison with myoepithelial markers. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:140–8.

Shinmura K, Kato H, Kawanishi Y, Kamo T, Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, et al. BSND is a novel immunohistochemical marker for oncocytic salivary gland tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2018;24:439–44.

McHugh JB, Hoschar AP, Dvorakova M, Parwani AV, Barnes EL, Seethala RR. p63 immunohistochemistry differentiates salivary gland oncocytoma and oncocytic carcinoma from metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:123–31.

Sciubba JJ, Shimono M. Oncocytic carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 209–81.

Skalova A, Michal M. Cystadenoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 273–4.

Tjioe KC, de Lima HG, Thompson LD, Lara VS, Damante JH, de Oliveira-Santos C. Papillary cystadenoma of minor salivary glands: report of 11 cases and review of the English literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:354–9.

Zhang S, Bao R, Abreo F. Papillary oncocytic cystadenoma of the parotid gland: a report of 2 cases with varied cytologic features. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:445–8.

Waldron CA, el Mofty SK, Gnepp DR. Tumors of the intraoral salivary glands: a demographic and histologic study of 426 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:323–33.

Goto M, Ohnishi Y, Shoju Y, Wato M, Kakudo K. Papillary oncocytic cystadenoma of a palatal minor salivary gland: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1220–2.

Sheetal Ramesh V, Balamurali PD, Premalatha B, Chaudhary M. Cystadenoma in retromolar region: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZD17–8.

Lanzel EA, Pourian A, Sousa Melo SL, Brogden KA, Hellstein JW. Expression of membrane-bound mucins and p63 in distinguishing mucoepidermoid carcinoma from papillary cystadenoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:521–6.

Mahmood H, Murphy C, Oktseloglou V. Cystadenoma of the mandible: a rare presentation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56:540–2.

Michal M, Skálová A, Mukensnabl P. Micropapillary carcinoma of the parotid gland arising in mucinous cystadenoma. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:465–8.

Budnick S, Simpson RHW. Cystadenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 191.

Vander Poorten V, Triantafyllou A, Skálová A, Stenman G, Bishop JA, Hauben E, et al. Polymorphous adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands: reappraisal and update. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:1681–95.

Richardson M, Bell D, Foschini MP, Gnepp DR, Katabi N. Ductal papillomas. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 192–3.

Foschini MP, Bell D, Katabi N. Sialadenoma papilliferum. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 192.

Agaimy A, Mueller SK, Bumm K, Iro H, Moskalev EA, Hartmann A, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of minor salivary glands with AKT1 p.Glu17Lys mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1076–82.

Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Karkavelas G, Papakonstantinou C, Papadimitriou CS. Sialadenoma papilliferum of the bronchus. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:695–9.

Hamilton J, Osborne RF, Smith LM. Sialadenoma papilliferum involving the nasopharynx. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:474–5.

Fowler CB, Damm DD. Sialadenoma papilliferum: analysis of seven new cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:193–201.

Abrams AM, Finck FM. Sialadenoma papilliferum. A previously unreported salivary gland tumor. Cancer. 1969;24:1057–63.

Argyres MI, Golitz LE. Sialadenoma papilliferum of the palate: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:259–62.

Mahajan D, Khurana N, Setia N. Sialadenoma papilliferum in a young patient: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e51–4.

Liu W, Gnepp DR, de Vries E, Bibawy H, Salomon M, Gloster ES. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising in a background of sialadenoma papilliferum: a case report. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:59–62.

Ponniah I. A rare case of sialadenoma papilliferum with epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;140:e27–9.

Shimoda M, Kameyama K, Morinaga S, Tanaka Y, Hashiguchi K, Shimada M, et al. Malignant transformation of sialadenoma papilliferum of the palate: a case report. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:641–6.

Brannon RB, Sciubba JJ. Ductal papillomas. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichert P, Sidransky D, editors. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 270–2.

Skalova A, Michal M. Cystadenoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichert P, Sidransky D, editors. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 273–4.

Asirvatham JR, Jorns JM, Zhao L, Jeffries DO, Wu AJ. Outcomes of benign intraductal papillomas diagnosed on core biopsies: a review of 104 cases with subsequent excision from a single institution. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:679–86.

Shiotani A, Kawaura M, Tanaka Y, Fukuda H, Kanzaki J. Papillary adenocarcinoma possibly arising from an intraductal papilloma of the parotid gland. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1994;56:112–5.

Batsakis JG, Brannon RB, Sciubba JJ. Monomorphic adenomas of the major salivary glands: a histologic study of 96 tumors. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1981;6:129–43.

White DK, Miller AS, McDaniel RK, Rothman BN. Inverted ductal papilloma: a distinctive lesion of minor salivary gland. Cancer. 1982;49:519–24.

Batsakis JG. Oral monomorphic adenomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:348–50.

Brannon RB, Sciubba JJ, Giulani M. Ductal papillomas of salivary gland origin: a report of 19 cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:68–77.

Berridge N, Kumar M. An interesting case of oral inverted ductal papilloma. Dent Update. 2016;43:950–2.

Henley JD, Summerlin D-J, Tomich CE. Condyloma acuminatum and condyloma-like lesions of the oral cavity: a study of 11 cases with an intraductal component. Histopathology. 2004;44:216–21.

Haberland-Carrodeguas C, Fornatoro ML, Reich RF, Freedman PD. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in oral inverted ductal papillomas. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:910–3.

Infante-Cossio P, Gonzalo DH, Hernandez-Gutierrez J, Borrero-Martin JJ. Oral inverted ductal papilloma associated with condyloma acuminata and HPV in an HIV+ patient. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:1159–61.

Sala-Pérez S, España-Tost A, Vidal-Bel A, Gay-Escoda C. Inverted ductal papilloma of the oral cavity secondary to lower lip trauma. A case report and literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013;5:e112–6.

Thompson LD, Bauer JL, Chiosea S, McHugh JB, Seethala RR, Miettinen M, et al. Canalicular adenoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 67 cases with a review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:181–95.

Samar ME, Avila RE, Fonseca IB, Anderson W, Fonseca GM, Cantin M. Multifocal canalicular adenoma of the minor labial salivary glands. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8205–10.

Peraza AJ, Wright J, Gómez R. Canalicular adenoma: a systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1754–8.

Ortega RM, Bufalino A, Almeida LY, Navarro CM, Travassos SC, Ferrisse TM, et al. Synchronous polymorphous adenocarcinoma and canalicular adenoma of the upper lip: an unusual presentation and immunohistochemical analysis. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:145–9.

Li J, Fonseca I. Basal cell adenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 187–8.

Wilson TC, Robinson RA. Basal cell adenocarcinoma and basal cell adenoma of the salivary glands: a clinicopathological review of seventy tumors with comparison of morphologic features and growth control indices. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:205–13.

Jo VY, Sholl LM, Krane JF. Distinctive patterns of CTNNB1 (ß-catenin) alterations in salivary gland basal cell adenoma and basal cell adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1143–50.

Sato M, Yamamoto H, Hatanaka Y, Nishijima T, Jiromaru R, Yasumatsu R, et al. Wnt/ß-catenin signal alteration and its diagnostic utility in basal cell adenoma and histologically similar tumors of the salivary gland. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:586–92.

Drut R. Cilindroma (tipo cutaneo) en la glándula parótida. Patologica. 1974;12:119–27.

Batsakis JG, Brannon RB. Dermal analogue tumours of the major salivary glands. J Laryngol Otol. 1981;95:155–64.

de Sousa MSO, de Araújo SN, Corrêa L, Pires Soubhia AM, de Araújo CV. Immunohistochemical aspects of basal cell adenoma and canalicular adenoma of salivary glands. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:365–8.

Bilal H, Handra-Luca A, Bertrand JC, Fouret PJ. P63 is expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of human normal and tumor salivary gland tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:133–9.

Luna MA, Tortoledo ME, Allen M. Salivary dermal analogue tumors arising in lymph nodes. Cancer. 1987;59:1165–9.

Li J, Fonseca I. Basal cell adenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 187–8.

Nagao T, Sugano I, Ishida Y, Matsuzaki O, Konno A, Kondo Y, et al. Carcinoma in basal cell adenoma of the parotid gland. Pathol Res Pract. 1997;193:171–8.

Iwai T, Baba J, Murata S, Mitsudo K, Maegawa J, Nagahama K, et al. Warthin tumor arising from the minor salivary gland. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e374–6.

Catania A, Falvo L, D’Andrea V, Biancafarina A, De Stefano M, De Antoni E. Parotid gland tumours. Our experience and a review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2003;55:857–64.

Hildebrand O. Über angeborne epitheliale Cysten und Fistelns des Halses. Arch Klin Chir. 1895;49:167–92.

Albrecht H, Arzt L. Beiträge zur Frage der Gewebsverirrung. Papilläre Cystadenome in Lymphdrüsen. Frankfurt Z Pathol. 1910;4:47–69.

Warthin AS. Papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum of the parotid gland. J Cancer Res. 1929;13:116–25.

Snyderman C, Johnsson JT, Barnes EL. Extraparotid Warthin’s tumor. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:169–75.

Ellies M, Laskawi R, Arglebe C. Extraglandular Warthin’s tumours: clinical evaluation and long-term follow-up. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:52–3.

Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Warthin’s tumor (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum). In: Rosai J, Sobin L, editors. Tumors the salivary glands. Fascicle 17, 3rd series. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1996. p. 68–79.

Nagao T, Gnepp DR, Simpson RHW, Viehl P. Warthin tumour. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 188–9.

Seifert G, Donath K. Multiple tumours of the salivary glands—terminology and nomenclature. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B:3–7.

Ethunandan M, Pratt CA, Morrison A, Anand R, Macpherson DW, Wilson AW. Multiple synchronous and metachronous neoplasms of the parotid gland: the Chichester experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:397–401.

Luers JC, Guntinas-Lichius O, Klussmann JP, Küsgen C, Beutner D, Grosheva M. The incidence of Warthin tumours and pleomorphic adenomas in the parotid gland over a 25-year period. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41:793–7.

Curry JL, Petruzzelli GJ, McClatchey KD, Lingen MW. Synchronous benign and malignant salivary gland tumors in ipsilateral glands: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Head Neck. 2002;24:301–6.

Zeebregts CJ, Mastboom WJ, van Noort G, van Det RJ. Synchronous tumours of the unilateral parotid gland: rare or undetected? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:62–6.

Maiorano E, Lo Muzio L, Favia G, Piattelli A. Warthin’s tumour: a study of 78 cases with emphasis on bilaterality, multifocality and association with other malignancies. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:35–40.

Chung YF, Khoo ML, Heng MK, Hong GS, Soo KC. Epidemiology of Warthin’s tumour of the parotid gland in an Asian population. Br J Surg. 1999;86:661–4.

Ethunandan M, Pratt CA, Higgins B, Morrison A, Umar T, Macpherson DW, et al. Factors influencing the occurrence of multicentric and ‘recurrent’ Warthin’s tumour: a cross sectional study. Int J Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:831–4.

Seifert G. Carcinoma in pre-existing Warthin tumors (cystadenolymhoma) of the parotid gland. Classification, pathogenesis and differential diagnosis (in German). Pathologe. 1997;18:359–67.

Foschini MP, Malvi D, Betts CM. Oncocytic carcinoma arising in Warthin tumour. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:88–90.

Moore FO, Abdel-Misih RZ, Berne JD, Zieske AW, Rana NR, Ryckman JG. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in a Warthin’s tumor of the parotid gland: pathogenesis, histopathology, and surgical management of malignant Warthin’s tumors. Am Surg. 2007;73:397–9.

Bell D, Luna MA. Warthin adenocarcinoma: analysis of two cases of a distinct salivary neoplasm. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:201–7.

Hellquist H, Skalova A, editors. Warthin tumour. In: Histopathology of the salivary glands. Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. p. 119–39.

Allevi F, Biglioli F. Squamous carcinoma arising in a parotid Warthin’s tumour. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-207870.

Yu C, Song Z, Xiao Z, Lin Q, Dong X. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising in Warthin’s tumor of the parotid gland: clinicopathological characteristics and immunophenotypes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30149.

Medeiros LJ, Rizzi R, Lardelli P, Jaffe ES. Malignant lymphoma involving a Warthin’s tumour: a case with immunophenotypic and gene rearrangement analysis. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:974–7.

Ozkök G, Taşlı F, Ozsan N, Oztürk R, Postacı H. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising in Warthin’s tumor: case study and review of the literature. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:579–82.

Arcega RS, Feinstein AJ, Bhuta S, Blackwell KE, Rao NP, Pullarkat ST. An unusual initial presentation of mantle cell lymphoma arising from the lymphoid stroma of Warthin tumor. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:209.

Melato M, Falconieri G, Fanin R, Baccarani M. Hodgkin’s disease occurring in a Warthin’s tumor: first case report. Pathol Res Pract. 1986;181:615–20.

Liu YQ, Tang QL, Wang LL, Liu QY, Fan S, Li HG. Concomitant lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Warthin’s tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:e117–20.

Pescarmona E, Perez M, Faraggiana T, Granati L, Baroni CD. Nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma associated with Warthin’s tumour. Histopathology. 2005;47:221–2.

Marioni G, Marchese-Ragona R, Marino F, Poletti A, Ottaviano G, de Filippis C, et al. MALT-type lymphoma and Warthin’s tumour presenting in the same parotid gland. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:318–23.

El-Naggar A, Batsakis JG, Luna MA, Goepfert H, Tortoledo ME. DNA content and proliferative activity of myoepitheliomas. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:1192–7.

Bombi JA, Alós L, Rey MJ, Mallofré C, Cuchi A, Trasserra J, et al. Myopeithelial carcinoma arising in a benign myoepithelioma: immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and flow-cytometrical study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1996;20:145–54.