Abstract

Despite a strong body of evidence demonstrating the importance of school belonging across multiple measures of wellbeing and academic outcomes, many students still do not feel a sense of belonging to their school. Moreover, school closures caused by COVID-19 lockdowns have exacerbated challenges for developing a student’s sense of school belonging. The current study used closed- and open-ended survey questions to explore student perspectives of practices influencing belonging in a sample of 184 Australian secondary school students. Thematic analysis of student responses to open-ended survey questions yielded four themes related to teacher-level practices influencing student belonging: emotional support, support for learning, social connection, and respect, inclusion and diversity. The implications of these findings are discussed, and strategies are suggested for implementing these student-identified practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

School belonging is a multidimensional dynamic construct outlining the extent to which students feel personally accepted, supported, and included by others in the school environment (Allen et al., 2021a, b; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Stickl-Haugen et al., 2019). Moreover, school belonging is systemic in nature, influenced by different contexts, experiences, and interactions that commonly occur in the school environment, such as classroom interactions (Allen et al., 2016a, b; Arslan et al., 2020). School belonging has been recognised as a significant predictor of a range of positive outcomes, such as improved psychosocial health (Steiner et al., 2019; Wyman et al., 2019), psychological wellbeing (Allen et al., 2016a, b; Arslan et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2016), positive school experiences (Korpershoek et al., 2020), and reduced instances of bullying, violence and substance use (Allen et al., 2021a, b; Arslan, 2022; Demanet & Van Houtte, 2012). The benefits of school belonging also appear to extend into adulthood, with a greater sense of belonging protecting against mental health decline, violence, risky sexual behaviour, and substance use (Steiner et al., 2019). Despite the benefits of school belonging established in the literature, little is understood regarding what interventions can intentionally build a sense of belonging in school (Allen et al., 2021a, b; Korpershoek et al., 2020). This is of concern given that student feelings of belonging have been gradually declining in Australia over the last several years (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2019), a trend that may now persist or worsen as schools begin to reopen post COVID-19 lockdown.

While a sense of belonging may be important for primary school-aged children (Palikara et al., 2021), it is particularly relevant from young adolescence onwards (ages 10 and up; Orben et al., 2020). Adolescence describes a period of rapid psychosocial development characterised by shifting social relationships, priorities and identity formation (Hill et al., 2013; Malin et al., 2014). This shift towards preferencing social relationships and identity formation is significant because school belonging is associated with positive identity development (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011; Davis, 2012) and is a protective factor against negative school-based outcomes (Steiner et al., 2019). Mental health problems in adulthood primarily originate in adolescence, with the onset of depression, anxiety, substance-use disorders, and the first episode of psychosis typically occurring while the individual is of school age (Allen & McKenzie, 2015; Bowman et al., 2017; Clarke et al., 2020). Experiencing mental health problems during school is associated with a greater risk of not graduating due to absenteeism, disruptive classroom behaviour, suspensions, or expulsions (Wigelsworth et al., 2017). There are several factors further associated with these negative outcomes, such as school climate, structure, and social interactions within school (Limone & Toto, 2022). The school setting is therefore a suitable location for interventions and practices aimed at addressing mental health problems in adolescents (Pechmann et al., 2020).

Belonging Post-lockdown

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, school belonging practices were being popularised throughout Australian schools (Allen et al., 2018; Norrish, 2015). However, the pandemic has likely played a role in the recent deterioration of young people’s mental health and wellbeing due to the unprecedented disruption to their education, development, and daily lives (Biddle & Gray, 2022; Butterworth et al., 2022). Globally, COVID-19 lockdowns exacerbated feelings of isolation, with reports of increased rates of depression and anxiety during lockdowns (de Miranda et al., 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020). While these experiences may have been universal during the pandemic, they were particularly salient for young people in countries that implemented strict and ongoing lockdown measures, such as Australia (Stobart & Duckett, 2022). As school attendance is strongly linked to a student’s sense of belonging in school (Bowles & Scull, 2019), and student–teacher relationships strongly influence feelings of belonging (Allen & Kern, 2017; Allen et al., 2016a, b; Crouch et al., 2014), the COVID-19 school closure periods may have impacted school belonging in students. Exploring student belonging perceptions during the COVID-19 lockdown periods can provide valuable insights into the intersection of school belonging, isolation, and mental health in the context of a global crisis. By understanding the effects of the pandemic on school belonging and mental health, interventions and support strategies can be tailored to address the specific needs of students and promote their wellbeing during challenging times.

Data from the Australian National University COVID-19 Impact Monitoring Survey found that as of January 2022, the psychological distress of Australians was at similar levels to what was experienced during the initial COVID-19 response (Biddle & Gray, 2022). This has been supported by longitudinal data, including measures taken post COVID-19 lockdowns, which found a statistically significant decline in mental health across the Australian population. Furthermore, a greater decline in mental health was experienced by individuals living in states experiencing stricter lockdown measures when compared to the rest of Australia (Butterworth et al., 2022). The effects of these worsening mental health outcomes were more concentrated in young Australians and among other vulnerable groups who also experienced the greatest increase in loneliness during the pandemic (Biddle & Gray, 2022). Research during the pandemic (i.e. Ford et al., 2021) has suggested that although some young people may be coping well, others are at risk of experiencing poor mental health outcomes from a combination of new stressors, such as reduced access to mental health and community services, and limited social interaction and support.

Generating Resources for Schools

A recent systematic review of adolescent school belonging interventions by Allen et al. (2021a, b) found that while several studies reported a positive effect of their intervention on student school belonging, very few interventions intentionally targeted school belonging from the outset, despite it being known to be an important factor in successful school outcomes, including mental health (Arslan, 2022; Arslan et al., 2020). However, the review highlighted that most schools recognised belonging and wellbeing as priorities for student outcomes (Allen et al., 2021a, b; see also Allen et al., 2018). Thus, to keep school belonging at the forefront of school policy and practice, it is paramount that evidence-based strategies and resources are easily accessible.

The Socio‑ecological Model of School Belonging

The socio-ecological model of school belonging, adapted from Bronfenbrenner (1994), emphasises the contribution and relationships between factors at different levels within the school system (such as the individual level, school policies, and class environments) as important contributors towards a student’s sense of school belonging (Allen et al., 2016a, b). Using a socio-ecological framework to understand student belonging is important as it centralises individual characteristics while also considering relational and environmental factors associated with school belonging (Allen et al., 2018, 2016a, b; Chiu et al., 2016). The framework includes six interconnected levels: the individual level, the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chronosystem (Allen et al., 2016a, b).

First, individual characteristics encompass student dispositional and biological characteristics that may influence other levels within the framework. Next, the microsystem focusses on student relationships with teachers, friends, family, and peers in the classroom. The mesosystem represents school policy, resources, management, and leadership, as well as the interplay between the individual level and the microsystem. The exosystem encompasses external organisations, other schools, the local community, and businesses that exist outside of the school. The next level is the macrosystem, which includes national or federal government influence, state educational institutions, and policy, as well as the cultural or historical context of each school. Last, the chronosystem outlines interactions across the socio-ecological levels across time. Within the socio-ecological framework, teachers’ capacity to provide social, emotional and academic support to their students is influenced by the broader context that they are working in, including school-wide policies and practices and the culture of the school environment.

Current Study

Despite a strong body of evidence demonstrating the importance of school belonging in contributing towards improved mental health and wellbeing, among a range of other positive outcomes for young people, research suggests that many students do not feel a sense of belonging in school (OECD, 2019). Given the impacts of COVID-19 and potential risks to student wellbeing associated with extended periods of disconnection from school due to lockdown, it is critical that opportunities to strengthen school belonging are identified and implemented.

Research has demonstrated that guidance from student perspectives when informing practice and policy has strengthened student learning and wellbeing (Anderson & Graham, 2016; Mitra, 2018). While the inclusion of student voice in educational research is growing in popularity (Cook-Sather, 2018), limited qualitative research exists in which student voice on belonging is elicited (cf. Craggs & Kelly, 2018; Due et al., 2016; Longaretti, 2020), especially regarding what improves belonging.

The current study employs a socio-ecological lens to examine student perspectives on school belonging, aiming to provide valuable insights for school leaders and administrators. By adopting this framework, the study seeks to identify student-identified practices that enhance school belonging, while acknowledging its multifaceted nature. The primary objective is to directly solicit solutions from students, giving voice to their experiences within the microsystem. While broader systems may also influence school belonging, the study prioritises microsystem-level dynamics reported by students as it best aligns with centring student perspectives. The current study aims to generate recommendations informed by students' perspectives, outlining specific actions for enhancing students' sense of school belonging. The research question guiding this study is: "Which practices do Australian secondary school students identify as promoting school belonging?".

Method

Participants

Participants included 184 Australian secondary school students aged between 12 and 20 years (M = 15.25; SD = 1.69) across Grades 7–12. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, students reported that they either learnt remotely, experienced a combination of both remote learning and school-based learning, or continued learning at school uninterrupted (see Table 1). Additionally, nearly half of the participants stated that their sense of school belonging stayed the same during COVID-19 (n = 85; 46.20%), and the remaining participants felt that their sense of belonging decreased (n = 76; 41.30%), or increased (n = 23; 12.50%). These differences could be attributed to variations in COVID-19 restrictions and lockdown schooling practices across states and regions in Australia throughout 2020 (Stobart & Duckett, 2022). All included participants were able to respond to the closed- and open-ended survey items. Participants who did not complete the survey beyond the demographics section were excluded from the study to avoid inflating the demographics.

Measures

An online survey was developed specifically for the purposes of this study, which included items related to participant demographic information, contextual information in relation to COVID-19 (e.g., state or territory lived in during lockdown, mode of school attendance during COVID-19), and impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on sense of school belonging. Student-identified belonging practices were explored through eight open-ended survey items asking for student opinions on belonging practices their schools and teachers currently implement, as well as what they could do to improve (e.g. “What could teachers do to improve your sense of belonging at school?”). Student perceptions of what they missed from school the most and the least during COVID-19 lockdown were asked, alongside why they felt their sense of school belonging increased, decreased, or stayed the same during COVID-19 lockdown.

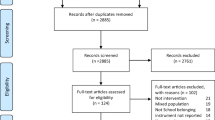

Procedure

Ethical approval for the current study was granted from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 25,737). Participants were eligible to participate if they were currently attending an Australian secondary or K-12 school, and if they had informed their parents of their involvement in the study. An invitation to participate in the study was distributed amongst the social networks of the research team in Australia and disseminated via an invitation using a range of social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. In addition, several social media influencers and prominent researchers and advocates in youth wellbeing shared information about the study within their social media networks. The online survey was accessed through a Qualtrics link and included an explanatory statement on the landing page describing what was involved in taking part in the study, in addition to outlining ethical considerations, including participant wellbeing, informed consent, confidentiality and the secure storage of information.

Participants provided informed consent by selecting a button prior to proceeding with the survey. In addition, participants were asked to indicate whether they had informed their parents/carers of their involvement in the research; if they selected no, they were unable to continue. The online survey was open for access between August and November 2020. During this period, most states and territories in Australia had reintroduced school-based learning after spending the earlier months of 2020 learning online from home (i.e. remote learning). This excluded the state of Victoria, which experienced a second extended lockdown from July to October 2020. Most Victorian students during this time were expected to engage in online remote learning from home, excluding only the children of parents who were classified as essential workers or children who had special needs. Due to the short and noninvasive nature of the survey, participants were not reimbursed for their time and participation was completely voluntary.

Planned Analysis

Demographic data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences 26 (SPSS-26). For the qualitative data collected through open-ended survey questions, a thematic analysis was conducted using the six steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (2013). The data were read and re-read (Step 1), inductively coded (Step 2), themes were generated and categorised (Step 3), then reviewed (Step 4). Finally, themes were named and defined (Step 5) and then outlined in this paper as a coherent narrative (Step 6). Since an inductive thematic analysis is facilitated by researcher engagement with the data, and directed by the content of the data, saturation is achieved only as an interpretive judgement related to the fulfilment of the studies aims (Braun & Clarke, 2019). An inductive thematic analysis was chosen as it allows flexibility in terms of epistemological and ontological orientation, while enabling a focus on participant experiences (Clarke & Braun, 2017). To ensure methodological rigour and the validity of identified themes and sub-themes, a senior member of the research team (KA) reviewed and further refined themes and sub-themes. This was a collaborative process involving meetings between the senior member of the research team (KA) and the researcher (FM) who conducted the initial analysis of the qualitative data. To measure the reliability of coding across different members of the research team, a Cohen’s Kappa calculation was conducted, revealing a Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient of κ = 0.81, indicating a strong inter-rater reliability.

Results

Student-Identified Belonging Practices

Thematic analysis of participant responses yielded four overarching themes and six sub-themes for practices that improved school belonging (see Table 2). The four main themes identified include: emotional support, support for learning, social connection, and respect, inclusion and diversity. Together, these present a narrative explicating what practices students feel would strengthen school belonging. All four overarching themes were valued by students both during COVID-19 lockdown and in the classroom environment. The following section describes each theme and provides representative extracts from the open-ended survey items to illustrate support for the analytic interpretations. Due to the large sample of responses, quotes will be tagged with a randomised number to distinguish them, along with student gender identity and age. Percentages of student responses for the open-ended survey items will not be included as it may be misleading to offer frequencies when students were not all asked to respond to specific themes.

Emotional Support

A common theme among students for improving belonging was emotional support from teachers. This support involved teachers “understand[ing] student emotional needs” (Participant 362, male, age 16), and having teachers “just show [they] care” (Participant 173, female, age 16) and “make sure you are okay” (Participant 188, female, age 13). Emotional support was particularly salient during lockdown, where students felt supported when “teachers took the time to check in…and make sure [students] were not only doing okay with school but coping mentally” (Participant 233, female, age 17). Two sub-themes were identified supporting this theme, including teachers being approachable and understanding, and teachers providing encouragement and opportunities to students.

Approachable and Understanding. Many students described the importance of teachers being approachable and understanding in supporting their sense of school belonging. Students described the importance of schools having teachers who students felt comfortable to “approach for help and guidance” (Participant 189, female, age 17). Here, teachers took on the role of being “a true mentor/friend” (Participant 291, female, age 17), not just a teacher in isolation. Teachers engaging with students, and checking in to see how they felt, or if they needed any support, were methods highlighted for breaking down this teacher–student barrier. For instance, one student commented that “[teachers] notice when I'm struggling and ask if I'm okay” (Participant 30, female, age 16). These teachers focussed on building “genuine connections through actively getting to know [students]” (Participant 30, female, age 16), taking an interest in the lives and wellbeing of students.

Encouragement and Opportunity. Students highlighted the importance of teachers providing encouragement and opportunities to strengthen student belonging in school. Teachers who “encourage more often… show the students they mean something to the school” (Participant 6, male, age 17). For students, it was important that teachers also recognised their effort and achievement, while providing opportunities for students to build on these, “see my talents, give me a chance, let me help others;” These “opportunities to be involved with lots of school activities” (Participant 20, male, age 16) provided students with the chance “to showcase [their] various talents and skills” (Participant 44, female, age 15). For some students, these opportunities were career pathways allowing students to “follow what they like” (Participant 7, male, age 15), for others these opportunities were in “clubs and extracurriculars” (Participant 297, female, age 18). However, many students felt during remote learning and lockdown that they were “losing the connection to extracurricular activities” (Participant 116, male, age 16).

As an extension to the Encouragement and Opportunity sub-theme, some students described the importance of teachers being less critical as a factor that supports their sense of school belonging. For example:

Don’t yell at the student if they get an answer wrong, we are trying to learn what you are teaching us but you have to remember this is one of the most confusing times in our lives and we are trying to discover who we are at the same time. (Participant 231, female, age 16)

While this criticism was often for academic mistakes, it also extended to uniforms, where “less concern about the uniform and more concern about the school work” (Participant 53, male, age 15) was valued by students. Here, students who were regularly criticised for uniform felt “alienated and like they have no place” (Participant 274, female, age 18).

Support for Learning

Support for learning was an important factor for improving school belonging. This theme was defined by two sub-themes: additional support and support for diverse learning needs. Importantly, this theme had strong ties to the effects of lockdown, where students felt “some content had not been fully learnt” (Participant 233, female, age 17) in their absence from the classroom environment. Together, these sub-themes indicated that students felt they belonged in school when they received support for their learning and education, especially during remote learning.

Additional Support. It was reported that teachers providing support for student learning was an important factor for their sense of school belonging. During lockdown, students felt they needed “extra support as remote learning is a lot harder” (Participant 246, female, age 16). For these students, they required additional check-ins and support to help them “catch up on school work from remote learning” (Participant 289, female, 12), rather than teachers “assuming [students] have learnt everything” (Participant 288, female, age 17). Outside of lockdown, “teachers who know what they are doing and know how to teach children and teenagers” (Participant 7, male, age 15) were highly regarded for their capacity and willingness to help when students were struggling. Important practices consistently mentioned by students included “progress checks to make sure everyone is working well,” if students were “falling behind with assigned schoolwork” (Participant 189, female, age 17), and offering “more resources” (Participant 35, female, age 16) such as practice tests and exams. These practices were applicable both during lockdown and remote learning, as well as in the classroom environment post-lockdown.

Support for Diverse Learning Needs. Fewer students described the importance of teachers providing support for learning that considered their diverse learning needs, as “every student learns differently” (Participant 104, female, age 16). For these students, teachers who “actually read [their] independent learning plan” (Participant 114, genderfluid, age 16) and made an effort to understand their educational needs were important for improving belonging. For some students, this involved adapting the curriculum or teaching pedagogy, to best meet their needs:

I have dyslexia and have been supported by teachers of language rich subjects. I have been offered alternative methods of presenting work such as by formal conversation, a platform I excel at. It has allowed me to continue my schooling with good enough grades to go to my ideal university. (Participant 104, female, age 16).

Being adaptable would “allow student who process information in different ways to do that, rather than trying to force one ‘acceptable’ learning method” (Participant 173, female, age 16). For other students, diversifying learning needs involved using a range of approaches to maintain the engagement of all students in learning, such as “making group activities and changing things up in class… [as] it gets boring having the same timetable for a whole semester” (Participant 245, female, age 12).

Social Connection

Social connection at school was an important teacher-level factor identified for improving student belonging. Similar to Support for Learning, this theme was closely tied to the effects of lockdown and the absence from the classroom environment. Here, “social based activities to build connections and bond with other students” (Participant 32, female, age 15) were highly valued. However, during lockdown students felt an overwhelming “lack of connection” (Participant 210, female, age 17) that extended to teachers, school peers, and extracurricular activities. For example, one student commented that their “sense of belonging decreased because [they] could no longer easily communicate with others in [their] school community and could no longer attend extracurricular school activities” (Participant 30, female, age 16). Two sub-themes emerged from this: support for connecting with peers, and support for becoming involved in school events/activities.

Connections with Peers. Teachers supporting students in connecting to their peers was important for belonging. Teachers could “promote more discussion in class across friend groups to prevent exclusion” (Participant 275, female, age 17), or “encourage engagement with lots of different people… [to] create a classroom environment that is welcoming and provides a sense of unity” (Participant 281, female, age 17). Under this sub-theme, teachers were seen as facilitators who had the capacity to provide students with “more social based activities to build connections and bond with other students” (Participant 32, female, age 15). Additionally, it was highlighted by students that post-remote learning teachers should provide classroom “activities to help the students re-connect after COVID” (Participant 89, female, age 15).

Involvement in School Events/Activities. A further practice identified as being important in strengthening school belonging included involvement in school events or activities. Getting students involved in extracurricular or cross-class activities could “create a sense of community among students of different year levels… [along with] teachers” (Participant 275, female, age 17). The diversity in friendship groups generated from this aligns with teachers facilitating connections with peers. For example, one participant commented on how they made friends through extracurricular activities at school: “one of the best things for me has been making friends with students older and younger than me through production and band and I think all students could benefit from having friends in other year levels” (Participant 275, female, age 17). Importantly, teachers needed to ensure that “no students are left out of group activities” (Participant 96, female, age 14) and that all students “engage and participate in school activities” (Participant 339, female, age 16), to promote an inclusive environment. Student involvement could be further promoted by schools through providing ample events/activities, such as “free dress days [where students are not expected to wear their school uniform], excursions, end of term celebrations” (Participant 19, female, age 14).

Respect, Inclusion and Diversity

Students reported teachers and schools as being respectful, inclusive, and recognised student diversity as important to their sense of belonging. For these students, respect extended to their opinions, culture, boundaries, disabilities and education. Respect was frequently highlighted as needing to be universal, which means “treating all students with the same level of respect” (Participant 44, female, age 15), and treating students “the same as everyone else instead of picking favourites and treating [only] them well” (Participant 74, female, age 14). The theme of respect, inclusion, and diversity is exemplified by the following:

I have dyslexia and dyscalculia, - formally diagnosed - but teachers think I'm just being lazy, not trying hard enough. I wish they could see how hard I'm really trying. Belonging would mean acceptance of people with disabilities and not treating us like trash. (Participant 332, male, age 15).

To promote inclusion and diversity, teachers can support “students who don’t fit into the popular/mainstream group, e.g. LGBTQ also international students” (Participant 275, female, age 17). Additionally, “teachers and students could learn about things like dyslexia and autism to make a more understanding environment” (Participant 3, female, age 13). While education and awareness was needed for inclusion and diversity to succeed in classroom environments, students also felt teachers needed to take “notice of any hateful language being said” (Participant 52, female, age 15). For example, one student commented that at their school “girls are taught about feminism and respectful relationships yet boys aren’t. Rape jokes and misogyny happen and it’s not cool” (Participant 4, female, age 18). Teachers could guide students in being “more empathetic, respectful and kind to one another to help students who don’t have a sense of belonging feel more comfortable and trusting” (Participant 247, female, age 15).

Discussion

Despite a strong body of evidence demonstrating the importance of school belonging for young people, including improved mental health and academic outcomes (Allen et al., 2016a, b; Arslan, 2022; Arslan et al., 2020; Korpershoek et al., 2020), student feelings of belonging have been gradually declining in Australia over the last several years (OECD, 2019). Given the recent and ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 lockdowns and potential risks to student wellbeing associated with extended periods of disconnection from school (Biddle & Gray, 2022; Butterworth et al., 2022), it is critical that opportunities to strengthen students’ school belonging are identified and implemented. In line with the socio-ecological framework of belonging, the current study sought to elicit the perspectives of secondary school students regarding practices that could build school belonging. The current study makes an important contribution to the literature by placing the perspectives of students at the centre of our inquiry concerning school belonging during and beyond COVID-19.

Student-Identified Belonging Practices

Four core belonging practices, identified as factors that improved a student’s sense of school belonging, emerged from the thematic analysis of student responses: emotional support, support for learning, social connection, and respect, inclusion, and diversity. These student-identified school belonging practices show a high level of concordance with recent findings derived from the school belonging literature (i.e. Allen & Kern, 2017; Allen et al., 2016a, b; Greenwood & Kelly, 2019), suggesting that social, emotional, and academic support provided by caring and empathic teachers is consistently one of the strongest predictors of a student’s sense of belonging at school. These practices have been linked to positive mental health outcomes, such as improved depressive symptoms, school burnout, and overall wellbeing (Pössel et al., 2013; Romano et al., 2021).

The finding that emotional support is important to a student’s sense of school belonging aligns with existing longitudinal data showing that teacher emotional support improves depressive symptoms in students and may be protective against school burnout (Pössel et al., 2013; Romano et al., 2021). While the specific connection between emotional support and school belonging has only recently been explored in the literature (Allen et al., 2016a, b; Arslan, 2018; Cai et al., 2022), the findings from this study provide further support for previous research highlighting the importance of positive adult relationships in their contribution towards improving mental health outcomes for young people (Anderman, 2003; Hattie, 2009; Tillery et al., 2013). The sub-themes identified under emotional support are not explicitly supported by the literature as improving belonging, though they are often identified as factors contributing to positive student–teacher relationships (e.g., Murray & Greenberg, 2001; Prewett et al., 2019; Sabol & Pianta, 2012; Singer & Audley, 2017). Additionally, teachers being approachable and understanding could be defined as practices displaying teacher empathy (e.g. Meyers et al., 2019), which is a teaching characteristic that has been demonstrated to play a role in improving student belonging (Cai et al., 2022).

Students in the current study felt that support for their learning was important to their sense of belonging, including additional curriculum support offered by teachers, and consideration of their diverse learning needs. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating that educational support and resources offered by teachers improved student feelings of belonging (Ozer et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2007; Van Ryzin et al., 2009). Consideration of the diverse learning needs of students is also an important factor when providing support for learning, particularly for students with special educational needs and disabilities, who often have a poorer sense of belonging than their peers (Capern & Hammond, 2014; Cullinane, 2020; Dimitrellou & Hurry, 2019). Interestingly, teaching assistants (which are employed and directed by schools and educational institutions) were not mentioned by students in the current study as being important to their sense of belonging. This contrasts with prior literature demonstrating that teaching assistants play a critical role in supporting students with special educational needs and disabilities, and contribute to perceptions about school and sense of belonging (Dimitrellou & Hurry, 2019; Webster & Blatchford, 2013). Given the potential consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is particularly significant to emphasise the heightened importance of teacher support for students' learning in the post-lockdown period. The transition from online learning back to the physical classroom setting may reveal learning difficulties faced by students who struggled or fell behind during the online curriculum (Doyle, 2020; Drane et al., 2020). Such challenges can have implications for students' mental health, as the disruption caused by the pandemic has heightened the need for comprehensive support systems within educational settings. By understanding the factors that contribute to students' sense of belonging and ensuring effective support, educators can play a pivotal role in promoting not only academic success but also the mental wellbeing of students.

Support to connect socially with others was identified as important to a student’s sense of belonging, including their connections to peers, and their ability to participate in school-based activities. This finding of social connection through activity participation in school is consistent with the literature, where variety and ease of participation in school-related events and activities is associated with improved belonging (Blomfield & Barber, 2010; Knifsend & Graham, 2012; Waters et al., 2010). Social connections with peers derived from these school activities, as well as those in the classroom, have been demonstrated to improve wellbeing, school belonging, and academic achievement (Kiefer et al., 2015; Van Ryzin et al., 2009; Wang & Eccles, 2012). The significance of social connection and support for student belonging places both teachers and schools in the role of facilitator, where they are responsible for not only encouraging social connection, but also for creating an environment full of opportunities for social connection to thrive in. These connections are closely tied to students' mental health, as positive social interactions and a sense of belonging contribute to their overall wellbeing (Santini et al., 2021).

Students in the current study described the importance of teachers valuing and supporting diversity, including sexual and gender diverse students, cultural differences, and students with additional learning needs. This is encapsulated through the theme of respect, inclusion and diversity, which is supported by recent research into the socio-ecological and demographic differences of school belonging in an Australian sample (Allen et al., 2021a, b). While this theme amalgamates several practices that could be used in isolation (i.e. inclusion), together these practices acknowledge the heterogeneity of students. Respect was placed first as it is of central importance when considering inclusivity and diversity, and should underscore all interactions with students (e.g. respect for diversity; Liang et al., 2020; Singer & Audley, 2017; Voight et al., 2015). This theme is consistent with school belonging research into the importance of supporting multiculturalism in the school environment (Celeste et al., 2019; Graham et al., 2022), student–teacher relationships for disabled students (Crouch et al., 2014; Dimitrellou & Hurry, 2019), and the role of schools in supporting sexual and gender diverse students (Dessel et al., 2017; Marraccini et al., 2022). Consideration of diversity and differences between students is even more important in the context of COVID-19, where there is mounting evidence indicating that the pandemic disproportionately affected already vulnerable young people, such as young carers (i.e. children caring for young or disabled siblings and/or parents), those with special needs, those living in poverty and overcrowded housing, and those whose parents experience mental health disorders (Viner et al., 2022). The links between school belonging, diversity, and mental health are crucial to consider, as promoting a sense of belonging among diverse student populations can have positive implications for their mental wellbeing (Cartmell & Bond, 2015; Georgiades et al., 2013).

Application of Student-Identified Practices

Given the strong alignment between the student-identified practices and the evidence base, many processes to support the implementation of the student-identified practices have been previously described in the literature (e.g. Allen & Kern, 2017; Allen et al., 2016a, b; Greenwood & Kelly, 2019). Several practical approaches could readily be implemented in schools, including the establishment of a school-wide vision and mission statement that prioritises school belonging (Allen et al., 2018; Stemler et al., 2011), the creation of policies and procedures to ensure a positive, safe, nurturing, and inclusive environment for all students (Chapman et al., 2014), and ensuring opportunities for student voice and choice-making are embedded within the school culture and curriculum (Greenwood & Kelly, 2019). Ensuring staff wellbeing and connectedness is prioritised at a policy and practice level is also of central importance in creating the conditions required to enable teachers to provide the social and emotional support for learning required to strengthen students’ school belonging (Bower et al., 2015; Noble & McGrath, 2008). Providing teachers access to professional learning and support (such as mentoring opportunities) to develop the skills and knowledge required to build positive relationships with students and to support student learning and wellbeing is another important approach (Chapman et al., 2014; Waters et al., 2010), as is the availability of specialised psychological support services for students when necessary (Bower et al., 2015; Greenwood & Kelly, 2019). The variability among these approaches indicates that there is no uniform approach to improving student belonging; therefore, both teachers and schools should make a judgement call on the practices and approaches that are best suited to their students’ current needs.

Limitations and Future Research

Although the current study makes an important contribution to the school belonging literature, findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. The sample was mainly English speaking, and so caution should be exercised when applying these findings to students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. This point is especially pertinant in the light of evidence suggesting that cultural status can be either a risk or protective factor for school belonging (Allen et al., 2021a, b; De Bortoli, 2018). Although some past research in school belonging has identified limited variability across countries (e.g. Willms, 2003), other research has indicated cultural considerations (Allen et al., 2021a, b). It will be important to compare the findings from this Australian sample to the results from other countries to better understand any variations in school belonging practices identified by students from different cultural backgrounds.

Data were collected over a four-month period, from August to November 2020 to allow collection of sufficient survey responses. During this period, some students may have been involved in examinations or variations in their study workload, which may have impacted on their survey responses due to the added academic stress. Also, there were variations across states and territories within Australia regarding the timing of lockdowns and periods of remote learning in 2020, with students in the state of Victoria experiencing a second lockdown during data collection for this study. As students were asked to reflect on their experience during COVID-19, some of the responses reported in this paper reflect the first wave of the virus only, while others reflect responses over two waves.

In the current study, the student-identified practices primarily centre around microsystem-level factors, specifically teacher practices. The students' perspectives primarily revolved around their classroom relationships and experiences, highlighting the crucial role of teacher support and interactions. Although other systems such as the mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem may influence school belonging, this study primarily emphasises the microsystem-level dynamics as reported by the students themselves. These findings underscore the immediate classroom environment and the significant contribution of teachers in fostering a sense of belonging among students. However, it is important to acknowledge the broader systems and contexts that facilitate and support teacher practices, including school policies, resources, and leadership. While the socio-ecological model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding school belonging, it is essential to interpret the study findings within the context of the student-centred perspectives that predominantly focus on microsystem-level dynamics, particularly teacher practices.

Conclusion

Following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and education of young people during lockdowns, it is of utmost importance that schools have access to evidence-informed approaches that can be readily implemented to strengthen school belonging for the future. The current study prioritises the voices of students, drawing on their perspectives to identify practices aimed at improving student school belonging. The results primarily focus on microsystems, particularly teacher practices. Even when students mention non-teacher microsystems like peers or extracurricular activities, it is often through the lens of teachers' influence. While the study acknowledges the importance of exo- and macro-systems in supporting teacher practices, the student perspectives mainly revolve around microsystems. This emphasises the need for cautious interpretation of the findings within the framework of Bronfenbrenner's model, as the students' perspectives predominantly reflect microsystems. The study's connection of student-identified solutions to the belonging literature provides a valuable resource for schools to implement practical approaches that enhance school belonging. These efforts have the potential to positively impact students' mental health, academic achievements, and social interactions. However, further research is needed to examine the specific relationship between the practices identified in this study and their effects on student mental health outcomes. By expanding our understanding of the intersection between school belonging and mental health, we can develop comprehensive strategies to support students' wellbeing and academic growth in the post-pandemic era.

References

Allen, K. A., Fortune, K. C., & Arslan, G. (2021a). Testing the social-ecological factors of school belonging in native-born, first-generation, and second-generation Australian students: A comparison study. Social Psychology of Education, 24(3), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09634-x

Allen, K. A., & Kern, M. L. (2017). School belonging in adolescents: Theory, research and practice. Springer.

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2016a). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Allen, K. A., Jamshidi, N., Berger, E., Reupert, A., Wurf, G., & May, F. (2021b). Impact of school-based interventions for building school belonging in adolescence: A systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09621-w

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2018). Understanding the priorities of Australian secondary schools through an analysis of their mission and vision statements. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(2), 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18758655

Allen, K. A., & McKenzie, V. L. (2015). Adolescent mental health in an Australian context and future interventions. International Journal of Mental Health, 44(1–2), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2015.1009780

Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016b). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

Anderman, L. H. (2003). Academic and social perceptions as predictors of change in middle school students’ sense of school belonging. The Journal of Experimental Education, 72(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970309600877

Anderson, D. L., & Graham, A. P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(3), 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

Arslan, G. (2018). Understanding the association between school belonging and emotional health in adolescents. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 7(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.2018.3117

Arslan, G. (2022). School bullying and youth internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Do school belonging and school achievement matter? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2460–2477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00526-x

Arslan, G., Allen, K. A., & Ryan, T. (2020). Exploring the impacts of school belonging on youth wellbeing and mental health among Turkish adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 13, 1619–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z

Biddle, N., & Gray, M. (2022). Tracking wellbeing outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (January 2022): Riding the Omicron wave. The ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University. https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2022/2/Tracking_paper_-_January_2022.pdf

Blomfield, C., & Barber, B. (2010). Australian adolescents’ extracurricular activity participation and positive development: Is the relationship mediated by peer attributes? Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 10, 114–128.

Bower, J. M., van Kraayenoord, & Carroll, A. (2015). Building social connectedness in schools: Australian teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Educational Research, 70, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.02.004

Bowles, T., & Scull, J. (2019). The centrality of connectedness: A conceptual synthesis of attending, belonging, engaging and flowing. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 29(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2018.13

Bowman, S., McKinstry, C., & McGorry, P. (2017). Youth mental ill health and secondary school completion in Australia: Time to act. Early Interventions in Psychiatry, 11(4), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12357

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Pergamon/Elsevier.

Butterworth, P., Schurer, S., Trinh, T. A., Vera-Toscano, E., & Wooden, M. (2022). Effect of lockdown on mental health in Australia: Evidence from a natural experiment analysing a longitudinal probability sample survey. The Lancet Public Health, 7(5), e427–e436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00082-2

Cai, Y., Yang, Y., Ge, Q., & Weng, H. (2022). The interplay between teacher empathy, students’ sense of school belonging, and learning achievement. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00637-6

Capern, T., & Hammond, L. (2014). Establishing positive relationships with secondary gifted students and students with emotional/behavioural disorders: Giving these diverse learners what they need. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 39(4), 46.

Cartmell, H., & Bond, C. (2015). What does belonging mean for young people who are international new arrivals. Educational & Child Psychology, 32(2), 89–101.

Celeste, L., Baysu, G., Phalet, K., Meeussen, L., & Kende, J. (2019). Can school diversity policies reduce belonging and achievement gaps between minority and majority youth? Multiculturalism, colorblindness, and assimilationism assessed. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(11), 1603–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219838577

Chapman, R. L., Buckley, L., Sheehan, M., & Shochet, I. M. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions of school connectedness and risk-taking in adolescence. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(4), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.771225

Chiu, M. M., Chow, B. W. Y., McBride, C., & Mol, S. T. (2016). Students’ sense of belonging at school in 41 countries: Cross-cultural variability. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(2), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115617031

Clarke, A., Pote, I., & Sorgenfrei, M. (2020). Adolescent mental health evidence brief 1: Prevalence of disorders. Early Intervention Foundation. https://www.eif.org.uk/report/adolescent-mental-health-evidence-brief-1-prevalence-of-disorders

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Cook-Sather, A. (2018). Tracing the evolution of student voice in educational research. In R. Bourke & J. Loveridge (Eds.), Radical collegiality through student voice (pp. 17–38). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1858-0_2

Craggs, H., & Kelly, C. (2018). Adolescents’ experiences of school belonging: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(10), 1411–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1477125

Crouch, R., Keys, C. B., & McMahon, S. D. (2014). Student–teacher relationships matter for school inclusion: School belonging, disability, and school transitions. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 42(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.855054

Cullinane, M. (2020). An exploration of the sense of belonging of students with special educational needs. REACH: Journal of Inclusive Education in Ireland, 33(1), 2–12.

Davis, K. (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.013

De Bortoli, L. (2018). PISA Australia in focus number 1: Sense of belonging at school. Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). https://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/30

de Miranda, D. M., da Silva Athanasio, B., Oliveira, A. C. S., & Simoes-e-Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: The differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9674-2

Dessel, A. B., Kulick, A., Wernick, L. J., & Sullivan, D. (2017). The importance of teacher support: Differential impacts by gender and sexuality. Journal of Adolescence, 56, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.002

Dimitrellou, E., & Hurry, J. (2019). School belonging among young adolescents with SEMH and MLD: The link with their social relations and school inclusivity. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1501965

Doyle, O. (2020). COVID-19: Exacerbating educational inequalities. Public Policy, 1–10.

Drane, C., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2020). The impact of ‘learning at home’ on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature Review prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University.

Due, C., Riggs, D. W., & Augoustinos, M. (2016). Experiences of school belonging for young children with refugee backgrounds. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.9

Ford, T., John, A., & Gunnell, D. (2021). Mental health of children and young people during pandemic. British Medical Journal, 372, n614. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n614

Georgiades, K., Boyle, M. H., & Fife, K. A. (2013). Emotional and behavioral problems among adolescent students: The role of immigrant, racial/ethnic congruence and belongingness in schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1473–1492.

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

Graham, S., Kogachi, K., & Morales-Chicas, J. (2022). Do I fit in: Race/ethnicity and feelings of belonging in school. Educational Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-022-09709-x

Greenwood, L., & Kelly, C. (2019). A systematic literature review to explore how staff in schools describe how a sense of belonging is created for their pupils. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2018.1511113

Guessoum, S. B., Lachal, J., Radjack, R., Carretier, E., Minassian, S., Benoit, L., & Moro, M. R. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hill, P. L., Allemand, M., Grob, S. Z., Peng, A., Morgenthaler, C., & Käppler, C. (2013). Longitudinal relations between personality traits and aspects of identity formation during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36(2), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.003

Kiefer, S. M., Alley, K. M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. Research in Middle Level Education Online, 38(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11641184

Knifsend, C. A., & Graham, S. (2012). Too much of a good thing? How breadth of extracurricular participation relates to school-related affect and academic outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(3), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9737-4

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Liang, C. T. H., Rocchino, G. H., Gutekunst, M. H. C., Paulvin, C., Melo Li, K., & Elam-Snowden, T. (2020). Perspectives of respect, teacher–student relationships, and school climate among boys of color: A multifocus group study. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000239

Limone, P., & Toto, G. (2022). Psychological strategies and protocols for promoting school well-being: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 914063. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.914063

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Longaretti, L. (2020). Perceptions and experiences of belonging during the transition from primary to secondary school. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 45(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2020v45n1.3

Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B., & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12051

Marraccini, M. E., Ingram, K. M., Naser, S. C., Grapin, S. L., Toole, E. N., O’Neill, J. C., Chin, A. J., Martinez, R. R., Jr., & Griffin, D. (2022). The roles of school in supporting LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and ecological framework for understanding risk for suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. Journal of School Psychology, 91, 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2021.11.006

Meyers, S., Rowell, K., Wells, M., & Smith, B. C. (2019). Teacher empathy: A model of empathy for teaching for student success. College Teaching, 67(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2019.1579699

Mitra, D. (2018). Student voice in secondary schools: The possibility for deeper change. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(5), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0007

Murray, C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2001). Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: Social emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 38(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(200101)38:1%3c25::AID-PITS4%3e3.0.CO;2-C

Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2008). The positive educational practices framework: A tool for facilitating the work of educational psychologists in promoting pupil wellbeing. Educational and Child Psychology, 25(2), 119–134.

Norrish, J. M. (2015). Positive education: The Geelong grammar school journey. Oxford Positive Psychology Series.

Orben, A., Tomova, L., & Blakemore, S. J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Sense of belonging at school. In PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What school life means for students’ lives. OECD.https://doi.org/10.1787/d69dc209-en

Ozer, E. J., Wolf, J. P., & Kong, C. (2008). Sources of perceived school connection among ethnically-diverse urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(4), 438–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558408316725

Palikara, O., Castro-Kemp, S., Gaona, C., & Eirinaki, V. (2021). The mediating role of school belonging in the relationship between socioemotional well-being and loneliness in primary school age children. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1882270

Pechmann, C., Catlin, J. R., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Facilitating adolescent well-being: A review of the challenges and opportunities and the beneficial roles of parents, schools, neighborhoods, and policymakers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(1), 149–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1136

Pössel, P., Rudasill, K. M., Sawyer, M. G., Spence, S. H., & Bjerg, A. C. (2013). Associations between teacher emotional support and depressive symptoms in Australian adolescents: A 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2135–2146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031767

Prewett, S. L., Bergin, D. A., & Huang, F. L. (2019). Student and teacher perceptions on student-teacher relationship quality: A middle school perspective. School Psychology International, 40(1), 66–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318807743

Romano, L., Angelini, G., Consiglio, P., & Fiorilli, C. (2021). The effect of students’ perception of teachers’ emotional support on school burnout dimensions: Longitudinal findings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041922

Sabol, T. J., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher–child relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Santini, Z. I., Pisinger, V. S., Nielsen, L., Madsen, K. R., Nelausen, M. K., Koyanagi, A., Koushede, V., Roffey, S., Thygesen, L. C., & Meilstrup, C. (2021). Social disconnectedness, loneliness, and mental health among adolescents in Danish high schools: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 632906. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906

Singer, A. F., & Audley, S. (2017). “Some teachers just simply care”: Respect in urban student-teacher relationships. Journal of Critical Education Policy Studies at Swarthmore College, 2(1), 5.

Steiner, R. J., Sheremenko, G., Lesesne, C., Dittus, P. J., Sieving, R. E., & Ethier, K. A. (2019). Adolescent connectedness and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics, 144(1), e20183766.

Stemler, S. E., Bebell, D., & Sonnabend, L. A. (2011). Using school mission statements for reflection and research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 383–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X10387590

Stevens, T., Hamman, D., & Olivarez, A., Jr. (2007). Hispanic students’ perception of White teachers’ mastery goal orientation influences sense of school belonging. Journal of Latinos and Education, 6(1), 55–70.

Stickl-Haugen, J., Wachter Morris, C., & Wester, K. (2019). The need to belong: An exploration of belonging among urban middle school students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2018.1556988

Stobart, A., & Duckett, S. (2022). Australia’s response to COVID-19. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 17(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133121000244

Tian, L., Zhang, L., Huebner, E. S., Zheng, X., & Liu, W. (2016). The longitudinal relationship between school belonging and subjective well-being in school among elementary school students. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11(4), 1269–1285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9436-5

Tillery, A. D., Varjas, K., Roach, A. T., Kuperminc, G. P., & Meyers, J. (2013). The importance of adult connections in adolescents’ sense of school belonging: Implications for schools and practitioners. Journal of School Violence, 12(2), 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.762518

Van Ryzin, M. J., Gravely, A. A., & Roseth, C. J. (2009). Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9257-4

Viner, R., Russell, S., Saulle, R., Croker, H., Stansfield, C., Packer, J., Nicholls, D., Goddings, A. L., Bonell, C., Hudson, L., Hope, S., Ward, J., Schwalbe, N., Morgan, A., & Minozzi, S. (2022). School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(4), 400–409.

Voight, A., Hanson, T., O’Malley, M., & Adekanye, L. (2015). The racial school climate gap: Within-school disparities in students’ experiences of safety, support, and connectedness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 56(3), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9751-x

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x

Waters, S., Cross, D., & Shaw, T. (2010). Does the nature of schools matter? An exploration of selected school ecology factors on adolescent perceptions of school connectedness. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909X484479

Webster, R., & Blatchford, P. (2013). The educational experiences of pupils with a statement for special educational needs in mainstream primary schools: Results from a systematic observation study. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28(4), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.820459

Wigelsworth, M., Qualter, P., & Humphrey, N. (2017). Emotional self-efficacy, conduct problems, and academic attainment: Developmental cascade effects in early adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1180971

Willms, J. D. (2003). Student engagement at school: A sense of belonging and participation: results from PISA 2000. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/33689437.pdf

Wyman, P. A., Pickering, T. A., Pisani, A. R., Rulison, K., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Hartley, C., Gould, M., Caine, E. D., LoMurray, M., Brown, C. H., & Valente, T. W. (2019). Peer-adult network structure and suicide attempts in 38 high schools: Implications for network-informed suicide prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13102

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organised by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Partial financial support was received from the Faculty of Education, Monash University from the Grand Challenges Scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation was contributed by Allen. Methodology was contributed by Allen, May, Berger, Reupert. Formal analysis and investigation were contributed by Allen and May. Writing—original draft preparation, was contributed by Allen and May. Writing—review and editing, was contributed by all authors. Funding acquisition was contributed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the conduct of the study was granted from Monash University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 25737).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, KA., Berger, E., Reupert, A. et al. Student-Identified Practices for Improving Belonging in Australian Secondary Schools: Moving Beyond COVID-19. School Mental Health 15, 927–939 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09596-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09596-9