Abstract

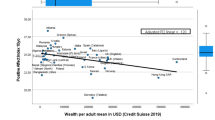

It is well established that child poverty has a profound, costly, and long-term impact on physical and mental health, educational attainment, and outcomes in adulthood. However, to date, while among adults a correlation between income and subjective well-being has been found, findings of such an association during childhood are mixed. This may be because the indicators available for both child poverty and subjective well-being have been limited – mainly to household incomes reported by adults and single measures of life satisfaction. This article explores the opportunities presented by the data collected in the third wave of Children’s Worlds, the school-based survey of children in 35 countries. The study employed a wider range of measures of material well-being, as well as subjective well-being, in terms of living standards in a larger range of countries. We have found that at both country comparative level, and within the country level, there is an association between material deprivation and some measures of subjective well-being, but the strength of the association varied between the country level and individual-level analyses, and across countries at the individual-level. At the macro-country level, the Family Affluence Scale was not significantly associated with most subjective well-being measures, while the deprivation scale, and a multi-dimensional measure that was developed in this paper, showed high correlations with overall life satisfaction and feelings of sadness. At the individual-level, the correlations were generally weak and varied between countries. We conclude with a discussion regarding possible explanations for these findings and their possible implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Code Availability

Codes are available in SPSS.

Data and Materials Availability

Data is available in SPSS.

Notes

Please note all tables shown refer to the 10-years-olds sample, unless it is stated differently in the title.

In some versions this is a holiday abroad.

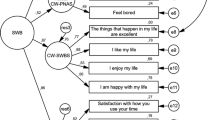

This was tested using two methods: firstly the structure of the measure was examined using exploratory factor analysis: all variables were found to load onto a single factor; secondly we tested the reliability of the scale using Cronbach’s Alpha: together, the scale had a score of 0.95, with one variable – I have what I want in my life – not making a substantial contribution, but neither would its removal enhance the scale substantially (Cronbach’s Alpha without = 0.96, a real difference of 0.001 when rounding is taken into account).

It should be noted the item ‘Things Life Excellent’ – was found to have somewhat diverse answering styles in different countries (Casas, 2020).

References

Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., & Korbin, J. E. (2014). Multifaceted concept of child well-being. Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp. 1–27)

Boyce, W., Torsheim, T., Currie, C., & Zambon, A. (2006). The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social Indicators Research, 78(3), 473–487.

Bradshaw, J., Keung, A., Rees, G., & Goswami, H. (2011). Children’s subjective well-being: International comparative perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(4), 548–556.

Bradshaw, J., Martorano, B., Natali, L., & De Neubourg, C. (2013). Children’s subjective well-being in rich countries. Child Indicators Research, 6(4), 619–635.

Bradshaw, J., Crous, G., & Turner, N. (2017). Comparing children’s experiences of schools-based bullying across countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 171–180.

Campbell, A. (1976). Subjective measures of well-being. American Psychologist, 31(2), 117.

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575.

Casas, F. (2020). Subjective Well-Being psychometric scales used in Children’s Worlds 3rd wave. Oradea: Scientific webinar on Child well-being in Romania.

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2019). Subjective well-being decreasing with age: New research on children over 8. Child Development, 90(2), 375–394.

Chzhen, Y. and C. de Neubourg (2014). Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis for the European Union (EU-MODA): Technical Note, Innocenti Working Paper No.2014–01, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence. Child Poverty Action Group (2019) All kids count: the impact of the two-child limit after two years, June 2019.

Crous, G. (2017). Child psychological well-being and its associations with material deprivation and type of home. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 88–95.

Crous, G., & Bradshaw, J. (2017). Child social exclusion. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 129–139.

Cummins, R. A. (2014). Understanding the well-being of children and adolescents through homeostatic theory. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being (pp. 635–661). Berlin: Springer.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., et al. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation.

de Neubourg, C., UNICEF, , et al. (2012). Child deprivation, multidimensional poverty and monetary poverty in Europe. Innocenti Research Centre: UNICEF.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276.

Elgar, F. J., Pförtner, T.-K., Moor, I., De Clercq, B., Stevens, G. W. J. M., & Currie, C. (2015). Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: A time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. The Lancet, 385(9982), 2088–2095.

Fattore, T., & Mason, J. (2017). The significance of the social for child well-being. Children & Society, 31, 276–289.

Feldman Barrett, L., & Russell, J. A. (1998). Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 967.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192–205.

Gordon, D. (2006). The concept and measurement of poverty. In C. Pantazis, D. Gordon, & R. Levitas (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in Britain: The millennium survey (pp. 29–70). Bristol: Policy Press.

Gross-Manos, D. (2015). Material deprivation and social exclusion of children: Lessons from measurement attempts among children in Israel. Journal of Social Policy, 44(01), 105–125.

Gross-Manos, D. (2017). Material well-being and social exclusion association with children’s subjective Well-being: Cross-national analysis of 14 countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 116–128.

Gross-Manos, D., & Shimoni, E. (2020). Where you live matters: Correlation of child subjective well-being to rural, urban, and peripheral living. Journal of Rural Studies, 76, 120–130.

Guio, A.-C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E., Najera, H., & Pomati, M. (2018). Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 11(3), 835–860.

Hansen, K. F., & Stutzer, A. (2020). Parental Unemployment, Social Insurance and Child Well-Being across Countries (p. 59)

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial Development of the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240.

Kern, M. R., Duinhof, E. L., Walsh, S. D., Cosma, A., Moreno-Maldonado, C., Molcho, M., Currie, C., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Intersectionality and Adolescent Mental Well-being: A Cross-Nationally Comparative Analysis of the Interplay Between Immigration Background, Socioeconomic Status and Gender. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S12–S20.

Knies, G. (2011). Life satisfaction and material well-being of young people in the UK. In L. McFall & C. Garrington (Eds.), Understanding Society: Early Findings from the first wage of the UK’s household longitudinal study. Colchester: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Lau, M., & Bradshaw, J. (2018). Material well-being, social relationships and children’s overall life satisfaction in Hong Kong. Child Indicators Research, 11(1), 185–205.

Levin, KN, Torbjorn T, Vollebergh W, Richter M, Davis CA, … Schnohr, C.W (2010) National Income and Income Inequality, Family Affluence and Life Satisfaction Among 13-Year-Old Boys and Girls: A Multilevel Study in 35 Countries. Social Indicators Research, 104(2), 179–194.

Mahony, S., & Pople, L. (2018). Life in the debt trap: Stories of children and families struggling with debt. Bristol: Policy Press.

Main, G. (2013). A child derivedmaterial deprivation index [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of York

Main, G. (2019). Child poverty and subjective well-being: The impact of children’s perceptions of fairness and involvement in intra-household sharing. Children and Youth Services Review, 97, 49–58.

Main, G., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). An index of child material deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 5(3), 503–521.

Main, G., & Mahony, S. (2018). Fair Shares and Families: Rhetoric and reality in the lives of children and families in poverty. The Children’s Society.

Main, G., & Pople, L. (2011). Missing out: A child-centred analysis of material deprivation and subjective well-being. The Children’s Society.

Main, G., Montserrat, C., Adrensen, S., Bradshaw, J., & Lee, B. J. (2019). Inequality, material well-being, and subjective well-being: Exploring associations for children across 15 diverse countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 97, 3–13.

Main, G. (2017). Child poverty and subjective well-being: The impact of children's perceptions of fairness and involvement in intra-household sharing. Children and Youth Services Review.

Marquez, J., & Inchley, J. (Forthcoming). A comparative study of factors explaining declining levels in adolescents’ life satisfaction: the importance of school well-being. Child Indicators Research.

Marquez, J., & Long, E. (2020). A global decline in adolescents’ subjective well-being: a comparative study exploring patterns of change in the life satisfaction of 15-year-old students in 46 countrie. Child Indicators Research.

Middleton, S., & Adelman, L. (2003). The Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey of Britain: Implications for the assessment of social security provision for children in Europe. In J. Bradshaw (Ed.), Children and Social Security. International Studies in Social Security (Vol. 8, pp. 1–34). Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Montserrat, C., Casas, F., & Moura, J. F. (2015). Children’s Subjective Well-Being in Disadvantaged Situations. In E. Fernandez, A. Zeira, T. Vecchiato, & C. Canali (Eds.), Theoretical and Empirical Insights into Child and Family Poverty. Children’s Well-Being: Indicators and Research. (Vol. 10). Springer.

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed. Paris: PISA OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en

Rees, G., & Bradshaw, J. (2018). Exploring Low Subjective Well-Being Among Children Aged 11 in the UK: An Analysis Using Data Reported by Parents and by Children. Child Indicators Research, 11(1), 27–56.

Rees, G., Pople, L., & Goswami, H. (2011). Understanding children’s wellbeing: Links between family economic factors and children’s subjective well-being: Initial findings from Wave 2 and Wave 3 surveys. The Children’s Society.

Rees, G., Goswami, H., & Pople, L. (2013). The good childhood report 2013. The Children Society.

Ridge, T. (2002). Childhood poverty and social exclusion: From a child's perspective (p. 178). Policy Press.

Saunders, P., & Naidoo, Y. (2009). Poverty, Deprivation and Consistent Poverty*. Economic Record, 85(271), 417–432.

Skattebol, J. (2011). “When the money’s low”: economic participation among disadvantaged young Australians. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(4), 528–33.

The Children’s Society. (2012). The Good Childhood Report 2012: A review of our children’s well-being. The Children’s Society.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. Middlesex, Penguin Books.

Von Rueden, U., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Bisegger, C., Ravens-Sieberer, U., et al. (2006). Socioeconomic determinants of health-related quality of life in childhood and adolescence: Results from a European study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(2), 130–135.

Zambon, A., Boyce, W., Cois, E., Currie, C., Lemma, P., Dalmasso, P., et al. (2006). Do welfare regimes mediate the effect of socioeconomic position on health in adolescence? A cross-national comparison in Europe, North America, and Israel. International Journal of Health Services, 36(2), 309–329.

Acknowledgements

The third wave of the Children’s Worlds survey was supported by the Jacobs Foundation.

Funding

The third wave of the Children’s Worlds survey was supported by the Jacobs Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Each participating country research team obtained needed ethical approval from the relevant academic institute, and the Ministry of Education if necessary.

Consent to Participate and for Application

Parents and children were asked for consent in a procedure explained in the method section (consent letters are available in Hebrew).

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gross-Manos, D., Bradshaw, J. The Association Between the Material Well-Being and the Subjective Well-Being of Children in 35 Countries. Child Ind Res 15, 1–33 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09860-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09860-x