Abstract

There has been an abundance of research on narcissism in the workplace. However, most research has focused on the overt (grandiosity) form of narcissism, as well as the effect of narcissism on uncivil behaviors of employees; research focusing directly on the effect of covert (vulnerability) narcissism on the employees’ experience of workplace incivility is lacking. The present research examined whether the personality trait (covert narcissism) of employees affects their experience of incivility considering two potential explanatory variables: self-esteem and perceived norms for respect. A total of 150 participants completed an online questionnaire, which consisted of four well-known measures: the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale, the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale, the Perceived Norms for Respect, and the Workplace Incivility Scale. The results showed that employees with higher levels of covert narcissism are likely to have greater experiences of workplace incivility through the mediating role of perceived norms for respect. Although the relationship was not explained through the mediating role of self-esteem, it was instead observed that self-esteem and perceived norms for respect jointly affect employees’ experience of incivility at work. These findings broaden our understanding of workplace incivility by simultaneously considering the influences of personality traits, self-esteem, and workplace norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The analysis of workplace misbehaviors (e.g., abusive supervision, workplace bullying and aggression) that inflicts both physical and psychological harm upon others in the workplace is a topic that has been vastly explored within psychology and organizational behaviors (Baron & Neuman, 1996; Folger & Baron, 1996; Vickers, 2014). Relatively recently, research regarding the impact of milder forms of psychological mistreatment where intents are ambiguous have also been paid attention to and conducted from the early 2000s in the same area (e.g., Cortina et al., 2017; Schilpzand et al., 2016). Experiences of interpersonal mistreatment often take subtle forms such as a lack of attention to an individual’s needs and ideas and being the target of demeaning remarks (Walsh et al., 2018). This type of behavior is referred to as workplace incivility, which is defined as deviant behaviors of low intensity with an ambiguous intention to harm others (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). That is to say, the expression of such behaviors may not be malicious or intentional from the perpetrator, but are characterized by rudeness, discourteousness and a display of lack of respect for others (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Indeed, most employees generally experience incivility at work, and it is increasing gradually in the organization (Cortina, 2008; Porath & Pearson, 2013; Schilpzand et al., 2016).

Despite the notion that the intensity and frequency of workplace incivility is low, the implications of incivility on the individual may be damaging and much longer lasting than the event itself. Workplace incivility has been identified as an influential cause that negatively affects work related outcomes (e.g., job performance, job satisfaction, work disengagement) and nonwork related outcomes (e.g., stress, emotional exhaustion, work-life imbalance) (see Irum et al., 2020 for a review). Porath and Pearson (2012) showed that experiencing incivility in the workplace can induce negative feelings for individuals. Specifically, Estes and Wang (2008) found that individuals who encountered high levels of workplace incivility experienced psychological issues associated with depression and anxiety. Furthermore, it was found that high exposure to workplace incivility can cause psychological stress and higher levels of employee absence due to illness (Salin, 2003). Moreover, workplace incivility negatively impacts on productivity and thus causes monetary loss for organizations (Hutton & Gates, 2008; Lewis & Malecha, 2011; Porath & Pearson, 2010).

Nonetheless, organizations often neglect to address workplace incivility, showing that only 20% of employees perceive an organizational response to the phenomena of workplace incivility (Pearson & Porath, 2004). In turn, this affects the functionality of organizations, as employees tend to reduce their efforts in the workplace, vent to their colleagues about their experiences related to perceived uncivil behavior and, in some cases, retaliate with uncivil behavior of their own (Pearson & Porath, 2005). The workplace incivility scale (WIS; Cortina et al., 2001) was developed as a way of measuring the frequency of rude, condescending, and disrespectful behaviors towards individuals within the past five years. Cortina et al. (2001) explained that incivility can occur at any level of the organizational structure; therefore, it is important to understand what leads to the experience of workplace incivility to prevent the negative outcomes resulting from such behavior. Meier and Semmer (2013) theorized that individual personality plays an important role in workplace incivility. Especially, narcissism has been portrayed as being at the heart of uncivil workplace behavior (Edwards & Greenberg, 2010; Judge et al., 2006). However, these works tended to focus on the aspect of overt narcissism (e.g., grandiosity, inflated self-view, preoccupation with success and power, sense of entitlement) and its effect on instigated workplace incivility (either intentionally or unintentionally showing uncivil behavior toward colleagues; one’s own behavior; cf. Blau & Andersson, 2005) and not on the experience of workplace incivility (one’s experienced behavior). Therefore, in the present study, we focus on the relationship between covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility considering the mediating role of self-esteem and perceived norms for respect.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

The Relationship between Covert Narcissism and Workplace Incivility

Narcissism generally refers to an individual’s tendency to act egocentric, dominant, and manipulative (Emmons, 1987), with unrealistic self-views, and is associated with strong feelings of either self-pity or entitlement, lacking in regard for others caused by a diminished interest in community and pro-social behavior (Campbell & Foster, 2007). Narcissism is a personality trait that is common amongst individuals within society (Foster & Campbell, 2007), which has led researchers to develop a multidimensional model of narcissism. One such classification is the distinction between overt narcissism and covert narcissism (Wink, 1991). Brookes (2015) found a non-significant correlation between overt narcissism and covert narcissism. These narcissistic forms are used to describe non-clinical personality traits that exist on a continuum (Freis & Brown, 2021).

While overt or Grandiosity-Exhibitionism form of narcissism is typically characterized by extroverted and expressed behaviors such as high levels of arrogance and excessive self-esteem, covert or Vulnerability–Sensitivity form of narcissism involves opposing, unexpressed behaviors (Luchner et al., 2011). Covert narcissism, while still characterized by entitlement and the need for admiration, is often manifested in terms of helplessness, shame, emptiness, low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression (Pincus & Roche, 2011; Rose, 2002; Wink, 1991). Furthermore, covert narcissists tend to rely heavily on the feedback of others to manage their self-esteem and have a strong avoidance motivation (Besser & Priel, 2010).

The research of narcissism and its positive relationship with workplace incivility is an area that has been previously explored by some researchers (e.g., Liu et al., 2020; Penney, 2003). For example, narcissists are more likely to react emotionally to workplace-based problems, which can result in individuals detaching themselves from their work entirely (Chen et al., 2013). Liu et al. (2020) found that narcissism was positively correlated with emotional reactions to workplace incivility showing that narcissistic people are more prone to anger when faced with workplace incivility. Furthermore, narcissistic individuals have a higher chance of experiencing workplace incivility due to their own perceived vulnerability, as well as being more likely to engage in workplace incivility themselves (Meier & Semmer, 2013).

However, these works tended to focus on overt narcissism; the empirical study of covert narcissism, which is displayed through vulnerability, a lack of confidence, deflated self-esteem, internalizing behavior, and hypersensitivity to others’ evaluation of oneself (Wink, 1991), has been largely ignored. This may be because overt (grandiose) narcissism is more widely associated with aggression, which is a means of defending and asserting grandiose self-views (Baumeister et al., 2000). For example, with regard to subtypes of aggression (proactive and reactive), overt narcissism is associated with both proactive and reactive aggression, but covert narcissism is associated with reactive aggression only (Fossati et al., 2010). Furthermore, previous research focused more on the effect of narcissism in people’s reactions to workplace incivility (Liu et al., 2020), rather than the effect of narcissism on people’s experience of incivility at work (i.e., narcissism as antecedent to the experience of workplace incivility).

To remedy this discrepancy in empirical knowledge, the present research aims to provide empirical evidence for the relationship between covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility. In the context of occupational health, given the related nature of covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility, covert (vulnerable) narcissism may be better suited as a predictor of experiencing workplace incivility compared to overt (grandiose) narcissism (cf. Wirtz & Rigotti, 2020). Thus, based on the prior research linking covert narcissism with experienced workplace incivility, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 1: Covert Narcissism will be positively related to the experience of workplace incivility.

The Role of Self-esteem

Self-esteem represents the evaluative area of the self-concept; it represents how individuals feel about themselves (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Originally, self-esteem was thought to be a one-dimensional construct, referring to a person’s general sense of worth (Rosenberg, 1965). High self-esteem acts as a cushion for people against negative emotion and feelings of anxiety, it enhances coping, and promotes physical and mental health (Taylor & Brown, 1988). Overall, individuals with low self-esteem are more likely to have introverted, shy, and socially anxious personality traits as well as experience negative and hurtful emotions (e.g., anxiety, fear, shame) more often than those with high self-esteem (Blackhart et al., 2009; Goswick & Jones, 1981; Leary & MacDonald, 2003; Richman & Leary, 2009). In line with covert (vulnerable) narcissism characteristics, individuals with low self-esteem often believe they are unimportant or undeserving of respect or attention (cf. Forest & Wood, 2012) and they are emotionally vulnerable and have lower intentions of interacting with others at work (Khezerlou, 2017).

Organizational research has shown that employees who experience a diminished sense of self are more likely to be frequent targets of workplace mistreatments (e.g., bullying, abusive supervision) (see Bowling & Beehr, 2006 for a review). This may be because they exhibit “victim-like” characteristics such as anxiety and fear, which makes others perceive them as vulnerable and weak (Aquino et al., 1999; Harvey et al., 2007; Vartia, 1996).

According to the Sociometer Theory (Leary & Baumeister, 2000), self-esteem functions as an interpersonal monitor of the extent to which an individual is assessed or devalued by others as a relational partner. That is, self-esteem could play a key role on people’s experience of workplace incivility in interpersonal relationship at workplace.

In the present research, we propose that employee’s perceptions of self-esteem will mediate the relationships between narcissism and workplace incivility. The wide body of prior research into narcissism shows that low self-esteem is an associated trait of covert narcissism (Brookes, 2015; Miller et al., 2011; Pincus & Roche, 2011; Rhodewalt & Eddings, 2002; Rohmann et al., 2012; Rose, 2002). This has led us to believe that there will be a negative relationship between covert narcissism and self-esteem. Furthermore, given the negative association between self-esteem and the experience of incivility in the workplace (Adiyaman & Meier, 2021; Meier & Semmer, 2013; cf. Bai et al., 2016), we expect that lower levels of perceived self-esteem will relate to higher levels of perceived experience of workplace incivility. Because low self-esteem is a major identifying factor of both covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility, we further predict that the relationship between covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility will be mediated by self-esteem. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

Hypothesis 2: Employee covert narcissism will be negatively related to self-esteem (hypothesis 2a) and self-esteem will also be negatively related to the experience of workplace incivility (hypothesis 2b), thus, self-esteem will mediate the relationship between covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility (hypothesis 2c).

The Role of Perceived Norms for Respect

Norms are commonly understood as the unwritten rules shared by members of the same group or society (Hecter & Opp, 2001) and are descriptive of what group members are as well as prescriptive of how they should be (Fiske, 2004; see also Morris et al., 2015). Norms for respect (climate for civility) can reflect perceptions of the degree to which dignity and respect among employees is encouraged and rude behaviors are discouraged within the workplace environment (Walsh et al., 2012). Workplace incivility occurs when a behavior violates the norms for respect (Andersson & Pearson, 1999), which suggests that norms can play an important role in the experience of incivility within organizations (Walsh et al., 2012).

Employees develop a perception of norms by assessing and applying meaning to actions and events they observe at work. Employee perceptions of organizational events are influenced based on information and opinions conveyed by co-workers and management (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). The way in which an individual perceives these norms forms their expectancies over the likelihood of certain acts will result in certain outcomes (James et al., 1990). For example, the kinds of events, practices, procedures and behaviors that are endorsed and supported within the workplace inform employees which behaviors are considered important and the outcomes they can expect to receive (Schneider, 1990). As such, when the work environment is perceived to value respectful treatment, employees would be less likely to experience incivility from others because individuals should act in consistency with their norm perceptions (Walsh et al., 2012). Indeed, recent evidence showed the negative correlation between perceived norms for respect and the experience of workplace incivility (Walsh et al., 2018). Although norms can be shared amongst employees as a group construct, the focus of the present study is individual perceptions of norms (Ehrhart & Naumann, 2004). This perspective is in line with existing research on norms for respect and psychological environment, capturing individual perceptions of the work settings (Parker et al., 2003; Walsh et al., 2012).

In the case of covert narcissism, such individuals may struggle to perceive norm violation in the same way as non-narcissists due to the covert narcissism’s characteristics of hypersensitivity, vulnerability, insecurity and vindictiveness (Wink, 1991). Individuals with high covert narcissism are hypersensitive to negative perceptions and judgements made by other people (Atlas & Them, 2008) and they are likely to interpret others’ actions as malevolent (Wink, 1991) and have negative perceptions of others (cf. Sedikides et al., 2004). Also, covert narcissists tend to immerse themselves in ways that do not gain other people's attention, respect, and praise (Atlas & Them, 2008). Hence, covert narcissists’ life satisfaction and self-esteem are low in general (Rose, 2002) which may be linked to negative perceptions of various situations (e.g., school/classroom climate, organizational climate; cf. Brockner et al., 1998; Lagacé-Séguin & d'Entremont, 2010). In turn, these overall negative perceptions of life act as sources of information which, consequently, influences individuals’ perceptions of norms (cf. Social information processing theory; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978; cf. Walsh et al., 2018). Because of the characteristics of hypersensitivity, it could be the case that information delivered by others is unlikely to be positively interpreted by covert narcissistic people. Also, considering covert narcissists’ heightened sense of importance and craving of admiration from their colleagues (Given-Wilson et al., 2011), they may show a greater likelihood that their perception of the workplace will equate to one that does not value fair treatment of employees. Thus, building upon this, we could assume that covert narcissists would have lower perceptions of norms for respect in their work environment.

Taken together, we propose that employee perceptions of norms for respect will mediate the relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility. High levels of covert narcissism will be negatively related to low instances of the perception of norms for respect. Additionally, given the negative association between employees’ perception of norms for respect and their experience of workplace incivility (Walsh et al., 2018), we contend that low perceptions of norms for respect will be related to high instances of perceptions of workplace incivility. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

Hypothesis 3: Covert narcissism will be negatively associated with perceived norms for respect (hypothesis 3a) and perceived norms for respect will also be negatively associated with the experience of workplace incivility (hypothesis 3b), thus perceived norms for respect will mediate the relationship between covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility (hypothesis 3c).

Present Research Aim and Model

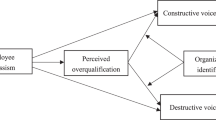

In the present research, we sought to examine the relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility considering the mediating roles of self-esteem and perceived norms for respect (Fig. 1). This was investigated through the lens of a research model developed based on prior literature. Firstly, low self-esteem is one of the main traits associated with covert narcissism, and it was found that self-esteem is negatively associated with the experience of uncivil or rude behaviors at work (Meier & Semmer, 2013). Secondly, central to the conceptualization of workplace incivility are norms for respect, and incivility, by definition, is behavior that violates norms for mutual respect (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Because narcissists may not perceive norm violation in the same way a non-narcissist does, perceived norms for respect becomes a suitable mediator to assess the relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility. By establishing significant links between these variables, we can help organizations implement their strategies and training to prevent incivility within the workplace. Furthermore, the present research can help explore the depth of organizational and individual health implications that derive from the association between covert narcissism and experienced incivility within the workplace through self-esteem and perceived norms for respect. Figure 1 presents the research model including the study hypotheses.

Method

Participants and Procedure

According to our priori power analysis based on five predictors (covert narcissism, self-esteem, norms for respect, income, SES) in the multiple regression, a medium anticipated effect size (f2 = 0.15) and a p value set at 0.05, a minimum of 138 participants are required to have a Power of 95% (Soper, 2021). A total of 150 participants who have had workplace experience within the last year were recruited from the United Kingdom. After ethical approval, an online survey was created using Qualtrics ® and disseminated through the human subject pool management system of the university (Sona Systems) and social media such as Facebook and Twitter asking for participation in a study to investigate the association between covert narcissism and workplace incivility. In the post of the study, the following inclusion criteria were clearly presented: (1) participants must be at least 21 years of age and (2) have been working a minimum of 5 years. These criteria were set in order to ensure that there were enough individual workplace experiences as required by Cortina et al.’s (2001) workplace incivility scale. The final sample consisted of 65 Men (43%) and 84 Women (56%) participants, with one participant choosing not to disclose their gender (< 1%). The average age of participants was 29.98 (SD = 11.04) and the age ranged from 21 to 59 years. Most participants identified themselves as white British (93%), with the majority being educated at least at an undergraduate level (62%).

The present study was approved by the Psychology Ethics Committee at the Leeds Beckett University and all participants provided their written informed consent after they had the opportunity to access a participant information sheet (PIS). There was no compensation for participation. To address the aims of the present research, a cross-sectional, quantitative, and non-experimental design was used. Willing participants were then asked to complete a survey with four main study variables (covert narcissism, self-esteem, perceived norms of respect, experience of workplace incivility). Participants first answered to the measure of covert narcissism (IV: independent variable) and last responded to the workplace incivility scale (DV: dependent variable). At the end, and after having provided further information on their demographic background, participants were thanked and debriefed.

Measures

Covert Narcissism

Hendin and Cheek’s (1997) Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS) has been suggested to be an adept measure of covert narcissism (cf. Brookes, 2015). It consists of a 10-item scale to measure individuals’ level of covert narcissism (e.g., “I am secretly "put out" or annoyed when other people come to me with their troubles, asking me for my time and sympathy”) that was answered on a 1–5 response scale (1 = very uncharacteristic/strongly disagree, 5 = very characteristic/strongly agree). The scoring level for this scale was between 10 (low) and 50 (high), a higher score on this survey indicates a higher level of personal covert narcissism. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.789 in this study.

Self-esteem

A commonly used Self-esteem scale (RSES) developed by Rosenberg (1965) was used to assess participants’ perceived levels of self-esteem. The scale consisted of 10-items with five items that were positive (Items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7; e.g., “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others”) and five items that were negative (Items 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10; e.g., “I feel I do not have much to be proud of”). Consistent with the original scale, negative items were scored in reverse direction prior to analysis. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale uses a 4-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.906 in this study.

Perceived Norms for Respect

Participants’ perceived norms for respect was measured using the following three items, which was developed by Walsh et al. (2018). An example item is “Overall, the organization values fair treatment and respectful interpersonal treatment among employees”. A 5-point response scale was used (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). This measure is scored out of 15. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.810 in this study.

Workplace Incivility

Cortina et al.’s (2001) workplace incivility scale (WIS), consisted of a seven-item scale, was used to measure participants’ experience of incivility in their workplace. Participants responded to 7 items that were presented by the following statement: “During the past year, while a member of your workforce, have you been in a situation where any of your superiors or co-workers…”. An example statement of the items was “Put you down or was condescending to you”. Participants answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = most of the time), with a higher score indicating a higher level of incivility occurrence. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.880 in this study.

Control Variables

Participants’ perceived level of social class and income were also measured as control variables given a lower socioeconomic status, considered a potential extraneous variable, may affect an individual’s perception of experienced workplace incivility (Reio & Ghosh, 2009; cf. Chaudhary et al., 2022; Miner et al., 2014 for further details). The perceived socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed using an 8-point ladder scale, with 1 being the lowest, and 8 the highest (Adler et al., 2000). Participants read the description: “Think of the ladder below as representing where people stand in our society. At the top of the ladder are the people who are the best off, those who have the most money, most education, and best jobs. At the bottom of the ladder are the people who are the worst off, those who have the least money, least education, and worst jobs or no job. The higher up you are on this ladder, the closer you are to people at the very top and the lower you are, the closer you are to the bottom. Where would you put yourself on the ladder? Please select the number below which corresponds to the rung where you think you stand”. Income was assessed on a 1–11 scale, with each item representing an amount of household income, for example, 1 equaled an income of less than £10,000, whereas 11 equaled an income of £150,000 or more.

Data Analysis Procedure

The data was analyzed using SPSS for windows version 26.0 and the SPSS PROCESS macro. Firstly, preliminary analyses including descriptive statistics and correlations were conducted. Then, regression analyses were conducted for each dependent variable to test H1, H2a, H3a (predictor variable = covert narcissism; control variables = SES and income). In order to test our posited research model (Fig. 1), a parallel mediation analysis following the procedure outlined in Hayes (2018, Model 4; cf. Igartua & Hayes, 2021) was performed. In this model (H2b, H2c, H3b, H3c were tested), covert narcissism served as a predictor variable (IV), experience of workplace incivility served as outcome variable (DV), whilst self-esteem and perceived norms of respect were treated as mediators. Furthermore, a sequential mediation analysis (Hayes, 2018, Model 6) was conducted as an exploratory model, in which self-esteem and perceived norms for respect were treated as sequential mediators (self-esteem → perceived norms for respect). In both parallel and sequential mediation models, perceived social class and income were treated as control variables. To ensure accurate estimates, a 95% percentile bootstrap confidence interval using 10,000 bootstrap samples was generated for the indirect effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics including the correlations between variables, means, standard deviations and z-score of skewness and kurtosis are presented in Table 1. Given absolute z-scores of skewness and kurtosis for the main study variables (not control variables, i.e., income) were smaller than 3.29, the normality assumption was not violated (Kim, 2013; cf. Field, 2018).

Dependent Variables (Hypotheses Testing)

Workplace Incivility (Hypothesis 1)

In the regression model [R2 = 0.45, F(3,146) = 12.21, p < 0.001], a significant relationship between covert narcissism and experience of workplace incivility was found, b = 0.34, SE = 0.06, t = 5.352, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.216, 0.469], supporting hypothesis 1. Workplace incivility was not affected by both income and SES, b = 0.08, SE = 0.18, t = 0.474, p = 0.636, CI95% [-0.268, 0.436] and b = 0.64, SE = 0.37, t = 1.736, p = 0.157, CI95% [-0.089, 1.371], respectively.

Self-esteem (Hypothesis 2a)

The regression model [R2 = 0.32, F(3,146) = 22.75, p < 0.001] showed, as expected, that higher levels of covert narcissism predict lower self-esteem, b = -0.37, SE = 0.06, t = -6.616, p < 0.001, CI95% [-0.478, -0.258], supporting hypothesis 2a. Self-esteem was not affected by income, b = 0.22, SE = 0.13, t = 1.55, p = 0.124, CI95% [-0.055, 0.448], but was affected by SES, b = -0.65, SE = 0.32, t = -2.03, p = 0.044, CI95% [-1.29, -0.017].

Perceived Norms for Respect (Hypothesis 3a)

As expected, covert narcissism negatively predicted perceived norms of respect [R2 = 0.26, F(3,146) = 16.86, p < 0.001], b = -0.17, SE = 0.03, t = -6.057, p < 0.001, CI95% [-0.221, -0.112], supporting hypothesis 3a. Perceived norms for respect was not affected by neither income nor SES, b = 0.07, SE = 0.08, t = 0.873, p = 0.384, CI95% [-0.085, 0.218] and b = -0.23, SE = 0.16, t = -1.42, p = 0.157, CI95% [-0.539, 0.088], respectively.

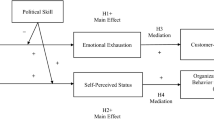

Parallel Meditation Analysis (Hypotheses 2b, 2c, 3b and 3c)

To test the assumption that covert narcissism would predict the experience of workplace incivility via both self-esteem and perceived norms for respect, parallel mediation analysis was conducted. The results revealed that both self-esteem and perceived norms for respect were negative significant predictors of the experience of workplace incivility [R2 = 0.38, F(3,146) = 17.37, p < 0.001], b = -0.19, SE = 0.09, t = -2.182, p = 0.031, CI95% [-0.367, 0.018], and b = -0.91, SE = 0.18, t = -5.115, p < 0.001, CI95% [-1.266, -0.560], respectively. Therefore, H2b and H3b were supported. Again, both control variables (income and SES) were found to have a nonsignificant effect on the outcome variable, b = 0.19, SE = 0.16, t = 1.18, p = 0.242, CI95% [-0.128, 0.503] and b = 0.31, SE = 0.33, t = 0.93, p = 0.356, CI95% [-0.351, 0.969], respectively.

The results of indirect effects showed that the relationship between covert narcissism and experience of workplace incivility was not significant via self-esteem, as zero fell within the confidence interval, b = 0.07, SE = 0.04, CI95% [-0.008 to 0.145], but was significant via perceived norms for respect as zero falls outside of the confidence interval, b = 0.15, SE = 0.04, CI95% [0.083 to 0.229]. Therefore, H2c was not supported, but H3c was supported (see Fig. 2). To be specific, the significant relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility became nonsignificant whilst controlling for the two mediators, b = 0.12, SE = 0.07, t = 1.754, p = 0.082, CI95% [-0.015, 0.254] (i.e., Direct effect of covert narcissism on the experience of workplace incivility). Again, the total effect (i.e., the relationship between the independent and dependent variables controlling the control variables, but without controlling the mediators in this relationship) on the relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility was significant, b = 0.34, SE = 0.06, t = 5.352, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.216, 0.469].Footnote 1

Collectively, these results provide evidence that the perceived norms for respect fully mediates the positive relationship between levels of covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility. Thus, the present results showed the double negative relationship between covert narcissism, norms for respect, and experience of workplace incivility, indicating a positive relationship between levels of covert narcissism and the experience of incivility through the perceived norms for respect. Hypotheses and outcomes for the present study are summarized in Table 2.

Serial Meditation Analysis

In the parallel mediation model, we observed the significant indirect effect of covert narcissism on incivility experience via perceived norms for respect, not via self-esteem. The unexpected nonsignificant indirect effect via self-esteem may be due to the strong indirect effect through perceived norms for respect. Also, the correlation results (cf. Table 1) showed that self-esteem was positively associated with perceived norms for respect. Building upon this, instead of treating these mediators independently, we treated them as sequential mediators (self-esteem → perceived norms for respect) in a new model. To test it, a sequential mediation analysis following the procedure outlined in Hayes (2018, Model 6) was performed. Again, perceived social class and income were treated as covariates in this model, and a 95% percentile bootstrap confidence interval using 10,000 bootstrap samples was generated.

The output of the regression model (i.e., covert narcissism and self-esteem are predictors and perceived norms for respect is the outcome variable; R2 = 0.32, F(3,146) = 16.84, p < 0.001), showed that perceived norms for respect was significantly predicted by covert narcissism (b = -0.12, SE = 0.03, t = -3.809, p < 0.001, CI95% [-0.175, -0.055]) and self-esteem (b = 0.14, SE = 0.04, t = 3.568, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.063, 0.219]). Perceived norms for respect was not affected by both income and SES, b = 0.04, SE = 0.07, t = 0.487, p = 0.627, CI95% [-0.111, 0.183] and b = -0.13, SE = 0.15, t = -0.867, p = 0.387, CI95% [-0.440, 0.172], respectively.

Although the indirect effect of covert narcissism on the experience of workplace incivility via self-esteem remained nonsignificant (b = 0.07, SE = 0.04, CI95% [-0.011 to 0.145]), the new indirect path from covert narcissism to the experience of workplace incivility via self-esteem (mediator 1) and perceived norms for respect (mediator 2) was significant (b = 0.05, SE = 0.02, CI95% [0.017 to 0.083]).Footnote 2 Consistent with the parallel mediation model, the indirect effect through the perceived norms for respect only remained significant in the sequential mediation model (b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, CI95% [0.043 to 0.179]) (see Fig. 3). Thus, the significant indirect path covert narcissism to individuals’ experiences of workplace incivility through the sequential influence of self-esteem and perceived norms for respect was observed; individuals with higher levels of covert narcissism would have greater levels of workplace incivility due to the decreased self-esteem was sequentially associated with decreased perceived norms for respect.

Discussion

The present research contributed to a better understanding of antecedents of employees’ experiences of workplace incivility. Specifically, the focus on the predictive role of employees’ level of covert narcissism extended previous research that primarily focused on overt (grandiose) or the total aspects of narcissism (overt + covert) and uncivil behavior at work (e.g., Baron & Neuman, 1996; Folger & Baron, 1996; Liu et al., 2020; Meier & Semmer, 2013; Vickers, 2014). This line of research comes at an important time as organizations begin to understand the costs of incivility (Johnson & Indvik, 2001; Pearson & Porath, 2004, 2005; Salin, 2003).

The present study tested two different paths (via self-esteem and norms for respect) for this relationship and the results suggest that perceptions of workplace norms for mutual respect only fully mediate the relationship between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility. In other words, although there was no direct link found between covert narcissism and the experience of workplace incivility, a positive relationship was established by the means of a double negative effect between the variables of covert narcissism and experienced workplace incivility through the mediating variable with perceived norms for respect. These findings reinforce the role that perceived norms for respect play in mediating covert narcissism on subtle forms of rude behaviors such as workplace incivility. Covert narcissists may perceive their work environment as a place to devalue fair and respectful interpersonal treatments due to their characteristics of hypersensitivity, insecurity and vindictiveness (Wink, 1991). Therefore, individuals with covert narcissistic traits are more likely to report that they have experienced incivility from colleagues due to the lowered level of perceived norms for respect. That is, individuals who work in an environment where all colleagues treat each other unfairly and behave in a disrespectful manner are more likely to experience workplace incivility (Walsh et al., 2012). This, in turn, affects the workplace effort from these individuals, as well as causing a negative attitude upon their peers and their workplace (Pearson & Porath, 2005). Considering workplace incivility is conceptualized as a norm violating behavior regarding mutual respect (Andersson & Pearson, 1999), employees’ experience of workplace incivility can be reduced by the increased level of norms for respect in workplaces. Our findings also support the relationship between perceived norms for respect and the experience of workplace incivility (e.g., Walsh et al., 2012, 2018) and also further suggest that the positive role of norms for respect may not be applicable to employees with high covert narcissism.

As expected, a significant relationship between high covert narcissism and low self-esteem was observed, which supports the previous research on this topic showing low self-esteem can be one of the main identifying traits of covert narcissism (Brookes, 2015; Miller et al., 2011; Pincus & Roche, 2011; Rhodewalt & Eddings, 2002; Rohmann et al., 2012). Consistent with previous research (Meier & Semmer, 2013), we also found that experience of workplace incivility was greater when self-esteem was low. However, unexpectedly we failed to observe the indirect effect of covert narcissism on the outcome variable via self-esteem showing that self-esteem itself may not be sufficient to explain how covert narcissism affects experience of workplace incivility. This may be because perceived norms for respect played the stronger mediating role in the research models.

According to Maslow (1987), self-esteem is the basic desire and need for self-respect, as well as the need for respect from others. Furthermore, modern self-esteem theory focuses on exploring why humans have motivation to appreciate themselves highly, and self-esteem can be defined as how favorably individuals evaluate themselves considering social acceptance (Baumeister & Bushman, 2010). According to sociometer theory (Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Leary et al., 1995), self-esteem evolves to reflect people’s level of status and acceptance in their social groups. Thus, self-esteem is related to respect from or acceptance by colleagues in groups. More directly, there is evidence that self-esteem predicts social respect for other persons in group such as school (Yelsma & Yelsma, 1998). We also found significant correlations between them. Building upon this, we further explored the serial mediation model by treating the two mediators in conjunction (self-esteem → perceived norms for respect; perceived norms for respect → self-esteem), which showed that only the direction from self-esteem to perceived norms for respect was significant suggesting that covert narcissists’ greater level of experience of workplace incivility can be explained by the negative effect of lowered self-esteem on perceived norms for respect, but not vice versa. According to a meta-analysis on the relationship between self-esteem and social relationship, our perception of others and our attitude toward them can be influenced by self-esteem (Harris & Orth, 2019). Hence, it could be the case that employees’ perceived norms for respect are influenced by their self-esteem considering that employees’ perceptions of organizational values and norms are affected by their important and meaningful relationship (managers or co-workers) at work (Walsh et al., 2018). Although findings from the serial mediation analyses were significant, the results were exploratory. Therefore, in order to confirm the validity of the findings, future studies should examine using a preregistered design with strong hypotheses.

Practical Implications

Given that most employees have experienced or witnessed workplace incivility (Porath & Pearson, 2010), incivility may be a common phenomenon in organizations. Hence, it is salient to understand incivility in the workplace and find the ways to reduce the negative consequences of incivility. The present research models can provide insight into how organizations can approach this problem. In particular, our model suggests the important role of norms for respect in workplace. Organizations should guide management to exhibit their desired organizational norms as a display to employees as this represents a viable point of intervention (Salisbury, 2009). Because employees’ perceived norms for respect are influenced based on portrayals from co-workers and management (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978), correct training for these individuals and an impetus to always act in a professional and civil manner will help fellow employees adopt these norms for themselves. To curb the perceived experience of incivility for covert narcissists, organizations need to invest a lot of time and effort creating norms for civility in organization. Employees' perceptions of norms can be developed through meaning and interpretation of various behaviors and events encountered during work life. Such perceptions can also be influenced by the opinions or information of colleagues or bosses/managers around them who have important relationships with them (Walsh et al., 2018). Indeed, there is evidence showing that charismatic and ethical leadership contributes to shaping employee’s perceptions that their organization emphasizes the importance of treating employees with respect and fairness (Walsh et al., 2018). This prevention approach is particularly more important to narcissistic employees because employees with high (vs. low) narcissism are more likely to disengage from their work when they have experienced workplace incivility (Chen et al., 2013).

Additionally, emotional intelligence training would assist employees who exhibit covert narcissistic traits to manage their emotional responses to violations of respect norms and workplace incivility, improving emotional intelligence and emotional regulation (Clarke, 2006; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Emotional intelligence training can improve individual health and wellbeing, job performance and alleviate feelings of aggression and depression (Cherniss & Adler, 2000; Schutte et al., 2007; Slaski & Cartwright, 2003), which have considerable long-term benefits for employees and organizations. Because covert narcissism is characterized by feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and depression (Pincus & Roche, 2011), emotional intelligence training would be an appropriate method to improve employees’ personal emotional outlook and reduce the impact of these feelings in the role of perceiving incivility at work. Indeed, emotional intelligence can help boost employees’ self-esteem in the organization (Dust et al., 2018; Johar et al., 2012). Therefore, employers should consider providing emotional intelligence training as a tool of improving self-esteem to their employees, which can sequentially improve the organizational culture of respect for others. Especially, emotional intelligence training is much needed for employees with higher covert (vulnerable) narcissism, given the fact that vulnerable narcissism is negatively associated with emotional intelligence and it was also associated with higher use of expressive suppression (as a response modulation/response-focused process) (for reviews see Walker et al., 2021, 2022). In other words, employers should invest more time, money, and effort to make emotional intelligence training successful because it may be more difficult to improve the emotional intelligence of employees with high covert narcissism due to their lower capacity of emotional regulation. It would be more effective to proceed with the training program with a long-term goal rather than a short-term goal.

Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations regarding the present research. Firstly, the unavailability of longitudinal data limits the support of a definite model, which could demonstrate whether the links between covert narcissism and incivility found in this study are stable over time. In order to firmly make inferences about causal relationships among study variables, longitudinal data is needed. Furthermore, the voluntary sample of participants were of a majority white background (92.5%), with most participants also having been educated to at least an undergraduate level (62%), which may affect generalizability of the findings to the wider population of the UK. Future research should aim to use a representative sample that is generalizable to the entirety of the UK population. Moreover, a recent study has explored the role of socio-demographic variables (e.g., duration of working hours, position in organizational hierarchy, education, nature or organization) in employees’ experience of workplaces (Chaudhary et al., 2022). Future work should consider the role of socio-demographic factors on employees’ experience of incivility at work.

Another limitation of this research is that the present research was conducted with a cross-sectional and non-experimental design which may inhibit inferences about causal relationship in our mediational research models (Winer et al., 2016). In other words, it is possible to test the effects of incivility experience on self-esteem and perceived norms for respect as our research models are atemporal mediation models. Indeed, we found significant reversed associations (see Table 1); experience of workplace incivility predicts both self-esteem (b = -0.38, SE = 0.07, t = -5.565, p < 0.001, CI95% [-0.514, -0.244]) and perceived norms for respect (b = -0.24, SE = 0.03, t = -7.781, p < 0.001, CI95% [-0.299, -0.178]). These findings are consistent with many previous evidence suggesting the negative impact of workplace incivility on employee’s psychological and occupational well-being (e.g., Adiyaman & Meier, 2021; He et al., 2020; Lim et al., 2008; Schilpzand et al., 2016), which can still contribute to literature on workplace incivility. Furthermore, we observed the indirect effects of workplace incivility on covert narcissism via self-esteem and perceived norms for respect. Nonetheless, the present research models are theoretically and empirically built based the previous literature. Importantly, the aim of the present work is to examine the effect of personality trait (covert narcissism) on people’s experience of workplace incivility, but not vice versa. To further understand this relationship, we treated self-esteem and perceived norms for respect as mediating variables.

A recent study has shown the association between narcissism and culture (Jauk et al., 2021). Especially, they found that vulnerable narcissism is less prevalent in Germany than Japan and it has a significant relationship with interdependent self-construal. They also suggested that, although the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and interpersonal problems can be observed across culture, vulnerable narcissism is more strongly related to interpersonal problems in a cultural context that values individualism and assertiveness. In addition, past studies have shown that people’s reaction to incivility can be affected by not only personality (narcissism), but also organizational and national culture (e.g., Liu et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2021; Moon & Sánchez-Rodríguez, 2021; Moon et al., 2018; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Tepper et al., 2017). Therefore, future research can extend the present findings on covert narcissism and workplace incivility by considering the role of culture at individual, organizational and national levels.

Although the present study showed that the higher level of covert narcissism of employees is associated with the greater experience of incivility at work due to the lower levels of self-esteem and perceived norms for respect, the results were based only on the role of covert narcissism without comparing with overt narcissism. Unlike covert narcissism, many studies have shown that overt narcissism is positively associated with self-esteem (e.g., Brookes, 2015; Raskin & Terry, 1988). Hence, we assume that the opposite patten would be observed; the higher level of overt narcissism of employees is related to the lower experience of workplace incivility due to the higher levels of self-esteem and perceived norms for respect. By investigating this prediction in the future work, the present findings can be strengthened.

Conclusion

Most previous literature on narcissism and incivility has focused on how narcissists, as instigators, are likely to show uncivil behaviors (e.g., Meier & Semmer, 2013; cf. Fennimore, 2020), instead of focusing on the effect of narcissism on experiences of workplace incivility. Also, researchers tended to focus on the overt (grandiosity) form of narcissism. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the relationship between covert narcissism and experience of workplace incivility has been investigated. We found evidence that employee’s narcissistic personality trait is associated with their experiences of workplace incivility, which was explained through (a) the perceived norms for respect and (b) the joint relationship between self-esteem and the perceived norms for respect (self-esteem → norms for respect). The finding of the present research contributes to expanding our understanding how personality traits (covert narcissism) affect employee’s experiences of incivility at work and provides insight into how organizations should approach this problem; boosting employee’s self-worth and creating and maintaining a culture of respect for others could be key to reduce individuals’ experiences of workplace incivility.

Data Availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the authors on reasonable request.

Notes

Note. A reversed parallel mediation model was tested upon request by the reviewer as an exploratory analysis. The total effect of workplace incivility on covert narcissism was significant, b = 0.48, SE = 0.09, t = 5.352, p < 0.001, CI95% [0.302, 0.656]. Both indirect effects via self-esteem and perceived norm for respect were significant, b = 0.16, SE = 0.05, CI95% [0.068, 0.256], b = 0.15, SE = 0.08, CI95% [0.023, 0.282], respectively. The direct effect of workplace incivility on covert narcissism was non-significant, b = 0.18, SE = 0.10, t = 1.754, p = 0.082, CI95% [-0.022, 0.373].

The model with reversed order of mediators (perceived norms for respect → self-esteem) was not significant, b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, CI95% [0.043 to 0.179]. Consistent with the other models, the indirect path via self-esteem was not significant, b = 0.06, SE = 0.03, CI95% [-0.008 to 0.132], but the indirect path via perceived norms for respect was significant, b = 0.18, SE = 0.05, CI95% [0.098 to 0.275].

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White Women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Adiyaman, D., & Meier, L. L. (2021). Short-term effects of experienced and observed incivility on mood and self-esteem. Work & Stress, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1976880.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of Incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Aquino, K., Grover, S. L., Bradfield, M., & Allen, D. G. (1999). The effects of negative affectivity, hierarchical status, and self-determination on workplace victimization. Academy of Management Journal, 42(3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.5465/256918

Atlas, G. D., & Them, M. A. (2008). Narcissism and sensitivity to criticism: A preliminary investigation. Current Psychology, 27(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-008-9023-0

Bai, Q., Lin, W., & Wang., L. (2016). Family incivility and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and emotional regulation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94(3), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.014

Baron, R., & Neuman, J. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence on their relative frequencies and potential causes. Aggressive Behavior, 22(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:3%3c161::AID-AB1%3e3.0.CO;2-Q

Baumeister, R. F., & Bushman, B. J. (2010). Social psychology and human nature. Cengage Learning.

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(1), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00053

Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(8), 874–902. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.8.874

Blackhart, G. C., Nelson, B. C., Knowles, M. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Rejection elicits emotional reactions but neither causes immediate distress nor lowers self-esteem: A meta-analytic review of 192 studies on social exclusion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(4), 269–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309346065

Blau, G., & Andersson, L. (2005). Testing a measure of instigated workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26822

Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.998

Brockner, J., Heuer, L., Siegel, P. A., Wiesenfeld, B., Martin, C., Grover, S., Reed, T., & Bjorgvinsson, S. (1998). The moderating effect of self-esteem in reaction to voice: Converging evidence from five studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.394

Brookes, J. (2015). The effect of overt and covert narcissism on self-esteem and self-efficacy beyond self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 172-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.013

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. J. Spencer (Eds.), The self (pp. 115–138). Psychology Press.

Chaudhary, R., Lata, M., & Firoz, M. (2022). Workplace incivility and its socio-demographic determinants in India. International Journal of Conflict Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-02-2021-0023

Chen, Y., Ferris, D. L., Kwan, H. K., Yan, M., Zhou, M., & Hong, Y. (2013). Self-love’s lost labor: A self-enhancement model of workplace incivility. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1199–1219. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0906

Cherniss, C., & Adler, M. (2000). Promoting emotional intelligence in organizations: Make training in emotional intelligence effective. AmericanSociety for Training and Development.

Clarke, N. (2006). Emotional intelligence training: A case of caveat emptor. Human Resource Development Review, 5(4), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484306293844

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000089

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

Cortina, L. M. (2008). Unseen injustice: Incivility as modern discrimination in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.27745097

Dust, S. B., Rode, J. C., Arthaud-Day, M. L., Howes, S. S., & Ramaswami, A. (2018). Managing the self-esteem, employment gaps, and employment quality process: The role of facilitation-and understanding-based emotional intelligence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(5), 680–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2265

Edwards, M. S., & Greenberg, J. (2010). Issues and challenges in studying insidious workplace behavior. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Insidious workplace behavior (pp. 309–354). Routledge.

Ehrhart, M. G., & Naumann, S. E. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in work groups: A group norms approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 960–974. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.960

Estes, B., & Wang, J. (2008). Workplace incivility: Impacts on individual and organizational performance. Human Resource Development Review, 7(2), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484308315565

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11.

Fennimore, A. (2020). That’s my stapler: Vulnerable narcissists and organizational territoriality. Management Research Review, 43(4), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-08-2019-0344

Field, A. (2018). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed). Sage

Fiske, S. T. (2004). Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. Wiley.

Folger, R., & Baron, R. A. (1996). Violence and hostility at work: A model of reactions to perceived injustice”. In G. R. VandenBos & E. Q. Bulatao (Eds.), Violence on the job: Identifying risks and developing solutions (pp. 51–85). American Psychological Association.

Forest, A., & Wood, J. (2012). When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychological Science, 23(3), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429709

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Eisenberg, N., & Maffei, C. (2010). Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 36(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20332

Foster, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2007). Are there such things as “narcissists” in social psychology? A taxometric analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1321–1332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.003

Freis, S., & Brown, A. (2021). Justifications of entitlement in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: The roles of injustice and superiority. Personality and Individual Differences, 168(1), 110345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110345

Given-Wilson, Z., McIlwain, D., & Warburton, W. (2011). Meta-cognitive and interpersonal difficulties in overt and covert narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1000–1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.014

Goswick, R. A., & Jones, W. H. (1981). Loneliness, self-concept, and adjustment. Journal of Psychology, 107(2), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1981.9915228

Harris, M. A., & Orth, U. (2019). The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1459–1477. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000265

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.), Guilford Press.

Harvey, M. G., Buckley, M. R., Heames, J. T., Zinko, R., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2007). A bully as an archetypal destructive leader. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 14(2), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071791907308217

He, Y., Walker, J. M., Payne, S. C., & Miner, K. N. (2020). Explaining the negative impact of workplace incivility on work and non-work outcomes: The roles of negative rumination and organizational support. Stress and Health, 37(2), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2988

Hecter, M., & Opp, K. (2001). Social norms. Russel Sage Foundation.

Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing Hypersensitive Narcissism: A Re-examination of Murray’s Narcissism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204

Hutton, S., & Gates, D. (2008). Workplace incivility and productivity losses among direct care staff. Workplace Health & Safety, 56(4), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.3928/08910162-20080401-01

Igartua, J. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2021). Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computations, and Some Common Confusions. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24(e49), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.46

Irum, A., Ghosh, K., & Pandey, A. (2020). Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding: A research agenda. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(3), 958–980. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-05-2019-0213

James, L. R., James, L. A., & Ashe, D. K. (1990). The meaning of organizations: The role of cognition and values. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 40–84). Jossey-Bass.

Jauk, E., Breyer, D., Kanske, P., & Wakabayashi, A. (2021). Narcissism in independent and interdependent cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 177, 110716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110716

Johar, S. S. H., Shah, I. M., & Bakar, Z. A. (2012). The impact of emotional intelligence towards relationship of personality and self-esteem at workplace. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.104

Johnson, P. R., & Indvik, J. (2001). Rudeness at work: Impulse over restraint. Public Personnel Management, 30(4), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600103000403

Judge, T. A., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. R. (2006). Loving yourself abundantly: Relationship of the narcissistic personality to self and other perceptions of workplace deviance, leadership, and task and contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 762–776.https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.762

Khezerlou, E. (2017). Professional self-esteem as a predictor of teacher burnout across Iranian and Turkish EFL teachers. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 5(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.30466/IJLTR.2017.20345

Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52

Lagacé-Séguin, D. G., & d’Entremont, M. R. L. (2010). A scientific exploration of positive psychology in adolescence: The role of hope as a buffer against the influences of psychosocial negativities. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 16(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2010.9748046

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 32(2000), 1–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9

Leary, M. R., & MacDonald, G. (2003). Individual differences in self-esteem: A review and theoretical integration. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 401–418). The Guilford Press.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518

Lewis, P. S., & Malecha, A. (2011). The impact of workplace incivility on the work environment, manager skill, and productivity. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 41(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182002a4c

Lim, S., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.95

Liu, P., Xiao, C., He, J., Wang, X., & Li, A. (2020). Experienced workplace incivility, anger, guilt, and family satisfaction: The double-edged effect of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109642

Luchner, A. F., Houston, J. M., Walker, C., & Houston, M. A. (2011). Exploring the relationship between two forms of narcissism and competitiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 779–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.033

Maslow, A. H. (1987). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). Harper and Row.

Meier, L. L., & Semmer, N. K. (2013). Lack of reciprocity, narcissism, anger, and instigated workplace incivility: A moderated mediation model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(4), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.654605

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x

Miner, K. N., Pesonen, A. D., Smittick, A. L., Seigel, M. L., & Clark, E. K. (2014). Does being a mom help or hurt? Workplace incivility as a function of motherhood status. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 60–73. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0034936.

Moon, C., Morais, C., de Moura, G. R., & Uskul, A. K. (2021). The role of organizational structure and deviant status in employees’ reactions to and acceptance of workplace deviance. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(2), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-03-2020-0036

Moon, C., & Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á. (2021). Cultural influences on normative reactions to incivility: Comparing individuals from South Korea and Spain. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(2), 292–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-05-2020-0096

Moon, C., Weick, M., & Uskul, A. K. (2018). Cultural variation in individuals’ responses to incivility by perpetrators of different rank: The mediating role of descriptive and injunctive norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2344

Morris, M. W., Hong, Y. Y., Chiu, C. Y., & Liu, Z. (2015). Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 129, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.03.001

Parker, C. P., Baltes, B. B., Young, S. A., Huff, J. W., Altmann, R. A., LaCost, H. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2003). Relationships between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(4), 389–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.198

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2004). On incivility, its impact and directions for future research. In R. W. Griffin & A. M. O’Leary-Kelly (Eds.), The dark side of organizational behavior (pp. 403–425). Jossey-Bass.

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature of consequences, and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841946

Penney, L. M. (2003). Workplace incivility and counterproductive workplace behaviour (cwb): What is the relationship and does personality play a role?, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Pincus, A. L., & Roche, M. J. (2011). Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 31–40). Wiley.

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2012). Emotional and behavioral responses to workplace incivility and the impact of hierarchical status. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(S1), E326–E357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01020.x

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2013). The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review, 91, 115–121.

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2010). The cost of bad behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 39(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.10.006

Reio, T. G., Jr., & Ghosh, R. (2009). Antecedents and outcomes of workplace incivility: Implications for human resource development research and practice. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(3), 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20020

Richman, L. S., & Leary, M. R. (2009). Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review, 116(2), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015250

Rhodewalt, F., & Eddings, S. K. (2002). Narcissus reflects: Memory distortion in response to ego-relevant feedback among high-and low-narcissistic men. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(2), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2002.2342

Rohmann, E., Neumann, E., Herner, M. J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2012). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Self-construal, attachment, and love in romantic relationships. European Psychologist, 17(4), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000100

Rose, P. (2002). The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(3), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00162-3

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890–902.

Salancik, G. J., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

Salin, D. (2003). Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Human Relations, 56(10), 1213–1232. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035610003

Salisbury, J. (2009). Coaching for respectful leadership. In E. Biech (Ed.), The 2009 Pfeiffer annual: Consulting (pp. 183–197). Pfeiffer.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(S1), S57–S88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1976

Schneider, B. (1990). Organizational climate and culture. Jossey-Bass.

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E. (2007). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(6), 921–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.003

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400

Slaski, M., & Cartwright, S. (2003). Emotional intelligence training and its implications for stress, health and performance. Stress and Health, 19(4), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.979

Soper, D. S. (2021). A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Multiple Regression [Software], available at: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193–210.

Tepper, B. J., Simon, L., & Park, H. M. (2017). Abusive supervision. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062539

Vartia, M. (1996). The sources of bullying–psychological work environment and organizational climate. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414855

Vickers, M. H. (2014). Towards reducing the harm: Workplace bullying as workplace corruption—a critical review. Employ Responsibilities and Rights Journals, 26, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-013-9231-0

Walker, S. A., Double, K. S., & Birney, D. P. (2021). The complicated relationship between the dark triad and emotional intelligence: A systematic review. Emotion Review, 13(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739211014585

Walker, S. A., Olderbak, S., Gorodezki, J., Zhang, M., Ho, C., & MacCann, C. (2022). Primary and secondary psychopathy relate to lower cognitive reappraisal: A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and emotion regulation processes. Personality and Individual Differences, 187, 111394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111394

Walsh, B. M., Magley, V. J., Reeves, D. W., Davies-Schrils, K. A., Marmet, M. D., & Gallus, J. A. (2012). Assessing workgroup norms for civility: The development of the Civility Norms Questionnaire-Brief. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27, 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9251-4

Walsh, B. M., Lee, J. J., Jensen, J. M., McGonagle, A. K., & Samnani, A. K. (2018). Positive leader behaviors and workplace incivility: The mediating role of perceived norms for respect. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(4), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9505-x

Winer, E. S., Cervone, D., Bryant, J., McKinney, C., Liu, R. T., & Nadorff, M. R. (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(9), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22298

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590

Wirtz, N., & Rigotti, T. (2020). When grandiose meets vulnerable: Narcissism and well-being in the organizational context. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(4), 556–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1731474

Yelsma, P., & Yelsma, J. (1998). Self-esteem and social respect within the high school. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549809600398

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Psychology Ethics Committee of Leeds Beckett University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moon, C., Morais, C. The effect of covert narcissism on workplace incivility: The mediating role of self-esteem and norms for respect. Curr Psychol 42, 18108–18122 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02968-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02968-5