Abstract

Narcissists have always been thought to have both positive and negative characteristics. However, the existing research regarding the ways that narcissistic employees express such positive and negative traits in organizations is still limited. The results of a longitudinal field study based on 450 participants of one Chinese firm to investigate the hypothesized model. The results show that employee narcissism has a positive effect on destructive voice via perceived overqualification. Moreover, organizational identification weakens the relation between employee narcissism and destructive voice via perceived overqualification. The results casts light on the mechanism between employee narcissism and voice. These findings provide significant insights for organizations in regard to the managing of narcissistic employees and overqualified employees. These findings also have important practical implications for organizations, enabling them to develop more appropriate human resource management strategies for narcissistic employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Narcissism has long been a central topic of research in clinical psychology, and organizational psychology (Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010). In the field of organizational research, narcissism is becoming more prevalent among new generations of employees. This characteristic has increased substantially over the last 30 years as both Eastern and Western cultures have become increasingly individualized and narcissistic (Cai et al. 2012; Sedikides et al. 2019; Twenge and Foster 2010). Narcissism is a widely prevalent personality unique characterized by a sense of grandiosity, self-love, dominance, and superiority (Spurk et al. 2016). Because of the significant harm caused and the exploitation of others, narcissistic persons are generally seen as destructive, abusive, or poisonous. For instance, narcissism has been positively linked to abusive leadership (Gauglitz et al. 2023) and counterwork behaviour (Judge et al. 2006; Penney and Spector 2002). While narcissism is often regarded as socially undesirable, a more comprehensive examination of narcissism has been called for in recent dark personality research (Jonason et al. 2014). According to Back et al. (2013), narcissists have both positive and negative characteristics because they adopt different social strategies to express their grandiose self. In recent organizational behaviour literature, there is a limited but increasing amount of evidence to demonstrate that narcissism may have some positive aspects for organizations (such as innovation behaviour, prosocial behaviour, taking charge, and whistle blowing) (Jalan, 2020; Konrath et al. 2016; Resick et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2017). Nevertheless, despite the burgeoning research on employee narcissism in the organizational context, our understanding of the conflicting roles of narcissists in organizations remains limited.

Voice has traditionally been defined as voluntary employee behaviour that is not been assigned a role description and is not rewarded outside of the role through a formal reward system; rather, it is a voluntary sharing of ideas, recommendations, concerns, or opinions regarding workplace issues with the objective of enhancing the organization’s operation (LePine and Van Dyne 2001; Morrison 2011). Although the study of employee voice has been the focus or significant literature over the past 20 years (Burris et al. 2013; Detert and Burris 2007; Morrison 2011), recent studies have revealed that most previous literature on voice has pay more attention on the positive forms of voice. Maynes and Podsakoff (2014) suggest that this narrow focus in past research may have precluded research on other types of voice (e.g., destructive voice). Hence, Maynes and Podsakoff (2014) proposed different dimensions of voice behaviour (e.g., preservation vs. challenge and promotive vs. prohibitive). Within the challenge voice behaviour dimension, constructive voice is described as the voluntary expression of ideas, facts, or opinions with the goal of creating organizationally functional change in the workplace, whereas destructive voice describes ideas that are undesirable, critical, or degrading concerning work policies or procedures. Generally, narcissists possess a feeling of grandiosity and entitlement (Credo et al. 2016). Thus, due to the overinflated egos of narcissistic employees, they may believe that they have unique competence at their workplace, which leads them to present suggestions regarding the organization and the work involved (Helfrich and Dietl 2019; Liu et al. 2022). Earlier research indicates that narcissistic individuals have both bright sides (e.g., innovation behaviour, prosocial behaviour, and whistle blowing) and dark sides (e.g., deviant behaviours and counterwork behaviour) (Fox and Freeman 2011; Khan and Chaudhary 2022; Penney and Spector 2002). Few prior empirical studies have been undertaken to investigate the impact of narcissism on voice (Helfrich and Dietl 2019). Narcissists have been considered to have both positive and negative characteristics because they adopt different social strategies to express their grandiose self (Back et al. 2013). This begs the following question: Do narcissistic employees apply challenge voice in both constructive and destructive ways? Based on this reasoning. The voice of narcissists can both benefit and undermine organizations; thus, there is a significant gap that needs to be addressed to understand the relationship between employee narcissism and employee voice behaviour.

Generally, people with narcissism have a tendency to develop an inflated sense of self as well as an inflated sense of their abilities and attributes (Maynard et al. 2015). Drawing on self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992), narcissistic employees adopt behaviours that are consistent with their self-concept, thereby reinforcing their self-concept and enhancing their sense of control over the external environment (Swann et al. 1992). The overinflated egos of narcissistic employees drive them to overestimate their capabilities in their job (perceived overqualification) and thereby lead them to express both constructive and destructive ideas towards the organization and its relevant work policies to fulfil their self-evaluation of their own uniqueness (Lobene et al. 2015). Therefore, the primary hypothesis of this study is to investigate the indirect relation between narcissism and constructive and destructive voice via perceived qualification.

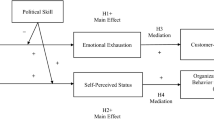

Organizational identification is a dynamic in which employees regard their organizational membership as part of their self-concept (Ashforth and Mael 1989). The more that an individual identifies with their organization, the greater the integration of organizational identity into his or her self-concept. In turn, individuals are more likely to engage in the behaviours that the organization expects of them to validate and reinforce their own judgements regarding their qualifications. Integrating social identity theory and self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992; Turner et al. 1979), we postulate that organizational identification weakens the relation between perceived overqualification and voice behaviour (constructive voice and destructive voice). When narcissistic employees have a higher degree of organisational identification, narcissistic employees who feel overqualified to obtain verification of their self-concept, thereby increasing the probability of their implementing their constructive voice and decreasing their destructive voice. Overall, we construct a theoretical model to test the indirect effect of employee narcissism on constructive and destructive voice via perceived qualification, while organizational identification serves to moderate this effect. Our conceptual framework is depicted in Fig. 1.

Our research makes three important contributions. First, while most prior studies of narcissism have paid great attention about narcissistic toxicity and its negative consequences (Grijalva and Newman 2015; Heintzelman and King 2013; Lobbestael et al. 2014), this study applies a holistic perspective on employee narcissism by investigating the effect of narcissism on both constructive and destructive voice. Second, by framing perceived overqualification as a mediator, this study takes a more comprehensive approach and examines a self-verification perspective that connects employee narcissism with voice behaviour. Last, by exploring the moderating effect of organizational identification, we offer a more complete theoretical explanation of how situational condition that influences the degree to which employee narcissism influences voice behaviour.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Employee narcissism and constructive voice

Voice behaviour can be conceptualized as an act of positive and discretional verbal expression that is not paid through company compensation system (Dyne and LePine 1998). Maynes and Podsakoff (2014) suggest that a status quo-challenging voice can be both constructive and destructive. In terms of constructive voice, employees may express new and constructive ways to fix existing work methods and procedures. We argue that employee narcissism is positively associated with constructive voice. First, because narcissism involves potential motivation that is related to a strong inner desire towards self-expression and self-enhancement, Narcissistic individuals may be inclined to generate ideas and provide suggestions to organizations (Martinsen et al. 2019; Wallace and Baumeister 2002). Narcissists’ self-improvement motivation makes them unafraid to express their opinions in status quo-challenging ways to benefit organizations (Liu et al. 2013). Second, narcissistic people have an inflated sense of self-esteem which leads to overconfidence and taking risks (Buyl et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2004). Consequently, narcissistic employees are likely eager to make public suggestions for change to satisfy their inflated egos. Thus, narcissistic employees might engage in constructive voice as a means of seeking continuous external self-affirmation and positive feedback as a means of fulfilling their grandiose self-views.

Hypothesis 1: Employee narcissism is positively related to constructive deviance.

Employee narcissism and destructive voice

Destructive voice is described as the voluntary voicing of harmful, critical, or demeaning ideas on work policies, procedures, and processes, among other things (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014). We suggest that narcissistic employees engage in destructive voice. Regarding the NARC model (Back et al. 2013), narcissism relates to the drive to restore and defend one’s perception of their superior position, especially compared with that of social competitors, which could lead to hostility, social insensitivity, and negative social consequences. Previous studies have developed the concept of “destructive” narcissism due to its potential negative influence on work-related outcomes (Back et al. 2013; Campbell et al. 2011; Higgs 2009). Narcissists have a feeling of entitled and might assume that they are exempt from organizational rules and express critical and potentially harmful opinions regarding views on workplace rules, practises, and processes (Grijalva and Newman 2015). O’Reilly and Chatman (2020) suggest that narcissists feel that they are exceptional and superior to others and that they often feel as if they do not receive the admiration and credit that they deserve. These emotions are frequently conveyed through hostile criticism and aggression (Li et al. 2016; Witte et al. 2002). Therefore, we predicted the following:

Hypothesis 2: Employee narcissism is positively related to destructive deviance.

The mediating role of perceived overqualification

Employee narcissism and perceived overqualification

Perceived overqualification is defined as people’s subjective feeling about his or her qualifications (education, skills, and work experience), specifically that qualifications exceed job requirements (Erdogan and Bauer 2021). We suggest that narcissism is likely to result in feelings of overqualification. First, narcissists tend to perceive themselves through an inflated view of self-importance that sets them above others (Judge et al. 2006), so they may have an inflated self-image of their own qualifications and overestimate those qualifications as exceeding the requirements of the job (Harari et al. 2017). Second, narcissistic individuals tend to highly value their worth and thus have very high expectations of the resources provided them by the job and an exaggerated sense of job fit, so narcissistic employees are likely to perceive themselves as being overqualified. Third, narcissists believe they are entitled and exceptionally gifted and disproportionately deserving of resources (Maynard et al. 2015). Hence, the narcissistic mindset of entitlement enables them to overestimate their talents and perceive themselves as being overqualified. Prior research has found that narcissistic employees have a high sense of their own overqualification (Harari et al. 2017). Therefore, we predicted the following:

Hypothesis 3: Employee narcissism is positively related to perceived overqualification.

Perceived overqualification and constructive voice

We propose that overqualified employees are inclined to implement constructive voice. First, people who perceive themselves as overqualified believe that they have an overabundance of expertise, abilities, talents, education, experience, and additional qualities. Hence, employees who perceive themselves as overqualified have more free time and cognitive resources to provide challenging ideas and proposals to the organization. Second, overqualified employees have inflated self-views of their own competence at work. Based on self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992), overqualified individuals may believe that they have an abundance of ideas and are inclined to exhibit vocal behaviour to satisfy their inflated self-concept. For example, employees with perceived overqualification hold a positive self-concept and have strong work motivation to engage in ideal tasks (Huang and Hu 2022; Ma et al. 2020). We suggest that overqualified employees might implement voice, expressing their ideas, information, and opinions, in constructive ways to verify their own qualification judgements. Thus, overqualified employees may have an inner desire to display OCB and voice behaviour to improve the status quo and verify their own self-views (Erdogan et al. 2020; Moorman and Harland 2002). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4: Perceived overqualification is positively related to constructive voice.

Perceived overqualification and destructive voice

Regarding the relative deprivation perspective (Bernstein and Crosby 1980), overqualified employees may experience disappointment, frustration and anger due to the mismatch between their qualifications and the job, which may further lead to disparaging comments regarding the organization’s policies and work-related programs. For example, because overqualified people possess more knowledge and abilities than is necessary for their professions, these employees experience anger at work and may react emotionally to the person-job misfit (Zhang et al. 2020). Previous research has revealed that stressful job experiences induce negative feelings and implement harmful and deviant workplace behaviour (e.g., counterwork behaviour) (Fine and Edward 2017; Johnson and Johnson 2000). As a result, the sense of mismatch that results from overqualification can also trigger destructive voice. Therefore, we predicted the following:

Hypothesis 5: Perceived overqualification is positively related to destructive voice.

Combining narcissism theory (Emmons 1987) and self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992), it can be seen that individuals strive for consistency in their self-concept to maintain a stable sense of control in a chaotic social environment and thus experience overqualification at work (Elliot and Thrash 2001; Grijalva and Zhang 2016; Zeigler-Hill and Besser 2013). Narcissistic people have inflated self-esteem and tend to exaggerate their talents, which promotes their experience of overqualification at work (Erdogan and Bauer 2021; Maynard et al. 2015). The experience of overqualification may, in turn, induce both constructive voice and destructive voice as a means of verifying narcissists’ inflated sense of self (Elliot and Thrash 2001; Grijalva and Zhang 2016; Zeigler-Hill and Besser 2013). Based on the preceding arguments, we predict:

Hypothesis 6: The relation between employee narcissism and constructive voice is mediated by perceived overqualification.

Hypothesis 7: The relation between employee narcissism and destructive voice is mediated by perceived overqualification.

Moderating effects of organizational identification

Organizational identification has been defined as the extent to which employees experience a sense of oneness or connection with their organisation and integrate organisational attributes in their self-definition (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994). Their positive self-regard is closely tied to their success and well-being (Dutton et al. 1994). A strong sense of identification creates a strong emotional connection to the organisation and a tendency to place the organization’s interests above one’s own (Pratt and Foreman 2000). A sense of organizational identity increases one’s sense of satisfaction with the organization and promotes extra role behaviours (Riketta and Dick 2005). We postulate that organizational identification moderates the effect of perceived overqualification on voice behaviour. In general, when overqualified employees identify strongly with their organization, it can serve as a marker for enacting or actualizing their positive self-views through constructive voice behaviour to obtain positive external evaluations. Previous studies suggest that overqualified individuals are more inclined to engage in extra work behaviour such as task crafting if they have a sense of organisational identification (Lin et al. 2017). Conversely, when overqualified employees do not identify with the organization or have a negative view of the organization, they may feel frustrated and meaningless and engage in a wider range of negative emotions, such as anger, disappointment, resentment, and boredom (Andel et al. 2021; Luksyte et al. 2011). Therefore, they may express complaints, criticism, and other destructive opinions to their organizations.

We have established a theoretical framework that link employee narcissism and voice behaviour. That is, narcissistic employees have inflated egos and more positive perceptions and evaluations of their own abilities and values, and this tendency drives narcissistic employees to make the most of their excess qualifications in suggesting ways to challenge the status quo in the organization. Their greater sense of organizational identification encourages narcissistic employees to implement positive and constructive advice; conversely, they may criticize the organization harshly. Reina et al. (2014) suggest that high organisational identification in narcissistic leaders connects the self-serving tendency of leader narcissism with organisational aims, which can further promote top management team behavioural integration and firm performance. Taken together, we expect that:

Hypothesis 8: Organizational identification moderates the relationship between perceived overqualification and destructive voice such that the relationship is weaker when organizational identification is higher (vs. lower).

Hypothesis 9: Organizational identification moderates the relationship between perceived overqualification and constructive voice such that the relationship is stronger when organizational identification is higher (versus lower).

Hypothesis 10: Organizational identification moderates the indirect effects of perceived overqualification arising from employee narcissism on destructive voice such that the relationship is weaker when organizational identification is higher (versus stronger).

Hypothesis 11: Organizational identification moderates the indirect effects of perceived overqualification arising from employee narcissism on constructive voice such that the relationship is stronger when organizational identification is higher (versus lower).

Methods

Participants

The participants were employed by a high-tech company located in Chengdu and Chongqing in southwestern China from March to July in 2022. They participated voluntarily and received personalization. We first informed the HR managers about the study and requested their participation. Second, all employees were informed about the study on the intranet. A multiwave (three waves, three weeks) and leader-follower dyad design was conducted to avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The data collection process involved distributing two separate questionnaires, one to employees and another to their immediate managers or supervisors. These questionnaires were matched by researcher-defined codes in preparation for the surveys. All surveys included postage-paid return envelopes. The research design was approved by the institutional ethical committee of the first author’s university, respondents provided informed consent and were ensured that their responses would remain confidential. In the first round, 810 participants reported information on their gender, age, education, tenure, and narcissism, and 712 returned fully completed questionnaires (87.9% response rate). At Time 2, 3 weeks later, 587 employees had completed surveys regarding their perceived qualification and organizational identification (82.44% response rate). Finally, at Time 3 (approximately 3 weeks after Time 2), we invited their direct leaders to measure the participants’ use of constructive voice and destructive voice over the past month. We received 190 responses (90.06% response rate). Overall, the dataset comprised 450 valid surveys. To improve the response rate, participants were compensated approximately RMB 30 for participation.

The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 55 (SD = 1.19). Approximately 51.3% were women. A total of 60.2% of participants reported having a bachelor’s degree, and a total of 47.6% of participants reported having more than 3 years of organizational tenure.

Measures

We used the translation processes provided by Brislin (1980) (The choices across narcissism assessment scores range from 0 to 1). Organizational identification, perceived overqualification, constructive voice, and destructive voice were categorized into a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert-type scale.

Employee narcissism

Employee narcissism was assessed using a16-item of Ames et al. (2006). A sample item is: “I truly like to be the centre of attention” (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.86).

Perceived overqualification

Perceived overqualification was assessed using a 9-item scale of Maynard et al. (2006). A sample item is: “I have more abilities than I need in order to do my job” (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.85).

Constructive voice

Constructive voice was assessed using a 5-item scale taken of Maynes and Podsakoff (2014). A sample item is: “I frequently make suggestions about how to do things in new or more effective ways at work” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88).

Destructive voice

Destructive voice was assessed using a 5-item scale of Maynes and Podsakoff (2014). A sample item is: “I frequently make overly critical comments regarding how things are done in my organization” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

Organizational identification

Organizational identification was assessed using a 5-item scale of Smidts et al. (2001). A sample item is: “I experience a strong sense of belonging to this organization” (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.87).

Control variables

Consistent with previous research (Bernerth and Aguinis 2016), Gender, age, education, and tenure were statistically controlled (Davidson et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2022; Mackey et al. 2020; Ng et al. 2021).

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

Table 1 shows the results of conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). As shown in Table 1, the five-factor model (employee narcissism, perceived qualification, organizational identification, constructive voice, and destructive voice) fit the data reasonably well (χ2 = 1492.81, df = 568, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.059) and performed better than the other models.

The composite reliability (CR) and average variance (AVE) were used to examine the convergent validity of the examined constructs. Based on acceptance criteria for CR and AVE (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Fornell and Larcker 1981). As indicated in Table 2 and Table 3, the discriminant validity and convergent validity were adequate in our study.

Descriptive statistics

As displayed in Table 4, There was a significant positive correlation between employee narcissism and perceived qualification (r = 0.47, p < 0.01) and destructive voice (r = 0.45, p < 0.01). A positive correlation was also found between perceived qualification was positively related to destructive voice (r = 0.50. p < 0.01).

Hypothesis testing

Based on the conclusions of the correlation analyses above, we first tested the indirect effect of employee narcissism and destructive voice via perceived qualification. After including all control variables, the results in Table 5 show that employee narcissism were significant predictors of perceived qualification (b = 0.47, p < 0.001) and destructive voice (b = 0.44, p < 0.001), and perceived qualification was positively related to destructive voice (b = 0.36, p < 0.001), thus validating Hypotheses 2, 3, and 5. We further examined the indirect impacts using a bias-corrected bootstrapping strategy (PROCESS, Model 4; Hayes (2013)). In support of Hypothesis 7, we discovered a significant indirect link between employee narcissism and destructive voice (indirect effect = 0.24, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.36]). Following the suggestions of Fey et al. (2023), low (−1 SD) versus high ( + 1 SD) values for the key independent variables were used to predict significant differences in the dependent variables of interest. Low (−1 SD) versus high ( + 1 SD) values of employee narcissism corresponded to a difference of 0.69 in the dependent variable (DV). We further examine the effect size of the indirect effect; the effect size of mediation is 0.22.

Second, we examined the moderating effect of organizational identification (Figs. 2, 3). We first centralized employee narcissism, perceived qualification, constructive voice, destructive voice, and organizational identification and then conducted interaction term tests. To investigate the moderating impact of organization identification. Based on PROCESS script (Model 7), the estimation among perceived qualification and organizational identification was highly significant for both constructive voice (b = 0.60, p < 0.05) and destructive voice (b = −0.84, p < 0.001) (Table 5). We next followed the recommendation of Aiken et al. (1990) and tested the significance of simple slopes for high and low levels of organization identification (1 SD above and below the mean value). A simple slopes analysis indicated that perceived qualification was positively related to constructive voice at high levels of organizational identification (b = 0.24, se = 0.10, p < 0.05), but was not significantly related to it at lower levels (simple slope = 0.63, ns). This finding partially supported Hypothesis 8. Furthermore, a simple slopes analysis indicated that perceived qualification was positively related to destructive voice at low levels of organizational identification b = 0.85, se = 0.10, p < 0.001) than at high levels of organizational identification (b = 0.53, se = 0.06, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 9.

Additionally, we examined the conditional indirect influence of organizational identity in moderated mediation model. Based on PROCESS syntax (Model 14), as displayed in Tables 6, 7, bootstrapping indicated that there was a significant conditional indirect relationship between team employee narcissism and destructive voice via perceived qualification, at higher ( + 1 SD) and lower levels (−1 SD) of organizational identification, the indirect relationship was stronger when organizational identification was high (Estimate = 0.67, se = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.522, 0.831]) than when organizational identification was low (Estimate = 0.39, se = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.268, 0.524]). These conditional indirect effects were significantly different from each other at (–1 SD) versus ( + 1 SD) was significant (∆b = 0.28, se = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.280, −0.289]). Thus, these results support Hypothesis 10, and Hypothesis 11 is not verified.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

In the last few decades, previous studies have revealed significant insight into the antecedents of voice behaviour (LePine and Van Dyne 1998; Ng and Feldman 2012; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Yet some fundamental questions remain unanswered. Drawing on self-verification theory and social identification theory, our results demonstrate how employee narcissism promotes destructive voice behaviour via perceived overqualification. Furthermore, organizational identification plays a critical role of moderating the indirect effect of narcissism on destructive voice behaviour. The current findings contribute to narcissism and voice research in various ways.

First, by answering the calls to explore the outcomes of narcissism (LeBreton et al. 2018), Our findings confirm the relation between employee narcissism and destructive voice. Although some research suggests a beneficial relationship between narcissistic personality and voice behaviour (Helfrich and Dietl 2019), to our knowledge, there has been no research conducted to determine whether employee narcissism implements voice behaviour in a constructive or destructive way. This study thus contributes to the dark trait and voice literature and suggests that employee narcissism can make employees more likely to express hurtful, critical, or debasing opinions of organizational policies in destructive ways. Based on self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992), narcissistic employees adopt behaviours that are consistent with their self-concept and thus serve to reinforce their self-concept (Swann et al. 1992). This study finds congruent evidence to support self-verification theory and suggests that narcissists have an inner desire for an inflated sense of self and consider of themselves as unique and superior to others, which impels them to display a destructive voice. Although previous studies suggest that employee narcissism can motivate employee destructive behaviour (Helfrich and Dietl 2019), consistent with previous studies, these results underscore the destructive nature of narcissism in organizational contexts (Campbell et al. 2011; Jonason et al. 2014). Taking a broader perspective, the present findings are in accordance with earlier study showing that employee narcissism often functions as a “bad apple” and is potentially harmful to organizations (Fox and Freeman 2011; Grijalva and Newman 2015). Interestingly, the research hypothesis of employee narcissism on constructive voice was not validated. A possible explanation for this result might be that narcissists’ inflated ego and sense of entitlement are better expressed through a destructive voice than through constructive voice. Nevertheless, given the relatively ambivalent findings on employee narcissism of previous studies (Credo et al. 2016; Fox and Freeman 2011; Grijalva and Newman 2015), our findings also extend and complement previous research on the potential double-edged sword effect of employee narcissism. This can benefit future studies by providing a more comprehensive and integrated perspective of employee narcissism.

Second, the present study supports the idea that perceived overqualification mediates narcissism-voice behaviour relationship. Based on self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992), The current study cast a novel insights into the inner mechanism underlying the relationship among employee narcissism and destructive voice. Our findings provides evidence that narcissistic employees could be driven by their self-concept, perceive themselves to be overqualified for their job and further implement destructive voice behaviour. Taking a broader perspective, voice behaviour has long been identified as a form of proactive behaviour (Strauss and Parker 2018; Tornau and Frese 2013). Although very few research have discovered a connection between employee narcissism and proactive behaviour (Liu et al. 2022; Roczniewska and Bakker 2016; Smith and Webster 2018), the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In particular, while previous studies have mostly used trait activation theory to explain how employee narcissism affects work-related outcomes (Zagenczyk et al. 2017), our findings seem to be consistent with and to extend the work of Helfrich and Dietl (2019) and Liu et al. (2022) by explaining the relationship among employee narcissism and destructive voice from a self-verification perspective. Hence, these findings broaden the knowledge of employee narcissism by showing that narcissists perceive themselves as overqualified and thus engage in destructive voice behaviour. Furthermore, comparative studies and theoretical developments provide some insight into how overqualification influences voice behaviour (Erdogan et al. 2020; Xia et al. 2019), and these findings responds to previous research and serve to expand previous research by suggesting a positive relation between perceived overqualification and destructive behaviour.

Third, our findings show that organizational identification moderates the relation between perceived overqualification and destructive voice behaviour and the indirect effect of employee narcissism on voice behaviour. From the perspective of self-verification theory (Swann et al. 1992) and social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael 1989), when overqualified staff lack to identify with the company or have a negative view of the organization, they may validate their inflated egos through negative voice. Our study supports the idea that when narcissistic staff members express a lack of organisational identity, they criticize the organization harshly. Although prior research has provided some insight into the positive association between narcissism and voice behaviour (Helfrich and Dietl 2019), only a handful of studies examined moderator variables for this relation. Only the study of Helfrich and Dietl (2019), which was based on a self-determination theory perspective, shows that the IFTs of leaders mitigate the detrimental effect of narcissistic rivalry on voice. Our study appears to go beyond that study because we demonstrate that organizational identification serves as a critical moderator in the indirect relation between narcissism and destructive voice behaviour. Previous study has mostly focused on the contextual variables that increase the negative aspects of narcissistic personality (Shah et al. 2020). Our result appears partially consistent with previous research and can be explained by the fact that in specific contexts, narcissistic employees are not always “bad apples” (Webster and Smith 2019).

Managerial implications

This study’s findings offer vital management implications for firms. First, the data indicate that employee narcissism is positively linked with destructive voice. When an organization recruits new employees, organisations should give some attention and caution to narcissistic job seekers. Specifically, probationary employment periods are ideal for capturing narcissism behavioural or character issues. If narcissistic people are hired into a company, collecting diverse viewpoints on performance is necessary (supervisor, coworker, and subordinate) that focus on ethical, interpersonal behaviour might aid in supressing their destructive effects. Second, the research argues that perceived overqualification mediates the link between employee narcissism and destructive voice. This finding implies that firms should be alert to the potential cost of recruiting overqualified personnel and should take the appropriate actions to reduce these costs. Thus, during recruitment and selection, organizations should hire individuals with the appropriate amount of KSAs (Knowledge, Skills & Abilities) to meet job demands. If overqualified individuals are recruited into an organization, organizations should also provide job rotation or training practices for employees to reduce their perception of their own overqualification. Last, according to our findings, organisational identification is a condition variable that inhibits the destructive voices of narcissistic employees. These findings suggest that cultivating and monitoring employees’ identification with their organization are effective strategies for minimizing destructive voice. Thus, organizations should improve person-job fit and enhance employee well-being to promote employee identification. Organizations should develop a flexible and healthy organizational culture to cultivate organizational identification and affiliation.

Limitations and future research directions

Some limitations of the study must be considered. First, data gathered at three different time points cannot be used to confirm the direction of causation. Future studies can employ qualitative research methods, experimental designs, and experience sampling approaches to establish causality. Second, narcissistic employees’ sense of entitlement leads them to violate the rules of social exchange, which in turn may affect their extrarole behaviour in the organization. Therefore, we hope that future studies will include social exchange perspective to unlock the relation between employee narcissism and voice behaviour. Third, we tested our model on only a single company in China, which is a context marked by collectivism and high power distance. How the findings generalize to other cultural contexts warrants future research. Future research can also include more sample companies and examine the cultural boundaries of culture-related variables (e.g., collectivism, uncertainty avoidance).

Data availability

Due to privacy considerations regarding this research, there are ethical restrictions on the sharing of data for this study. The ethics committee has not agreed to the public sharing of data as we do not have the participants’ permission to share their anonymous data. Additionally, the dataset contained personal information about the participants, and despite efforts to anonymize the data, it is possible to identify the participants. Qualified and interested researchers may request access from the corresponding author.

References

Aiken LS, West SG, Sechrest L et al. (1990) Graduate training in statistics, methodology, and measurement in psychology: A survey of PhD programs in North America. Am Psychol 45:721–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.6.721

Ames DR, Rose P, Anderson CP (2006) The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. J Res Pers 40(4):440–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.03.002

Andel S, Pindek S, Arvan ML (2021) Bored, angry, and overqualified? The high-and low-intensity pathways linking perceived overqualification to behavioural outcomes. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 31(1):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1919624

Ashforth BE, Mael F (1989) Social identity theory and the organization. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):20–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4278999

Back MD, Küfner ACP, Dufner M et al. (2013) Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. J Pers Soc Psychol 105:1013–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034431

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16(1):74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

Bernerth JB, Aguinis H (2016) A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol 69(1):229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

Bernstein M, Crosby F (1980) An empirical examination of relative deprivation theory. J Exp Soc Psychol 16(5):442–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90050-5

Brislin RW (1980) Cross-cultural research methods. In: Altman I, Rapoport A, Wohlwill JF (eds) Environment and culture. Springer, Boston, MA, pp 47–82

Burris ER, Detert JR, Romney AC (2013) Speaking up vs. being heard: the disagreement around and outcomes of employee voice. Organ Sci 24(1):22–38. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0732

Buyl T, Boone C, Wade JB (2019) CEO narcissism, risk-taking, and resilience: an empirical analysis in U.S. Commercial banks. J Manag 45(4):1372–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317699521

Cai H, Kwan VSY, Sedikides C (2012) A sociocultural approach to narcissism: the case of modern China. Eur J Pers 26(5):529–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.852

Campbell WK, Goodie AS, Foster JD (2004) Narcissism, confidence, and risk attitude. J Behav Decis Mak 17(4):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.475

Campbell WK, Hoffman BJ, Campbell SM, Marchisio G (2011) Narcissism in organizational contexts. Hum Resour Manag Rev 21(4):268–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.007

Credo KR, Lanier PA, Matherne CF, Cox SS (2016) Narcissism and entitlement in millennials: the mediating influence of community service self efficacy on engagement. Pers Individ Differ 101:192–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.370

Davidson T, Van Dyne L, Lin B (2017) Too attached to speak up? It depends: how supervisor–subordinate guanxi and perceived job control influence upward constructive voice. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 143:39–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.07.002

Detert JR, Burris ER (2007) Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J 50(4):869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV (1994) Organizational images and member identification. Adm Sci Q 39(2):239–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235

Dyne LV, LePine JA (1998) Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad Manag J 41(1):108–119. https://doi.org/10.5465/256902

Elliot AJ, Thrash TM (2001) Narcissism and motivation. Psychol Inq 12(4):216–219

Emmons RA (1987) Narcissism: theory and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol 52(1):11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11

Erdogan B, Bauer TN (2021) Overqualification at work: a review and synthesis of the literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 8(1):259–283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-055831

Erdogan B, Karaeminogullari A, Bauer TN, Ellis AM (2020) Perceived overqualification at work: implications for extra-role behaviors and advice network centrality. J Manag 46(4):583–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318804331

Fey CF, Hu T, Delios A (2023) The Measurement and Communication of Effect Sizes in Management Research. Manag Organ Rev 19(1):176–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2022.2

Fine S, Edward M (2017) Breaking the rules, not the law: the potential risks of counterproductive work behaviors among overqualified employees. Int J Sel Assess 25(4):401–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12194

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Fox S, Freeman A (2011) Narcissism and the deviant citizen: a common thread in CWB and OCB. In: Perrewé PL, Ganster DC (eds) The role of individual differences in occupational stress and well being. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 151–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3555(2011)0000009009

Gauglitz IK, Schyns B, Fehn T, Schütz A (2023) The Dark Side of Leader Narcissism: The Relationship Between Leaders’ Narcissistic Rivalry and Abusive Supervision. J Bus Ethics 185(1):169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05146-6

Grijalva E, Newman DA (2015) Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): meta-analysis and consideration of collectivist culture, big five personality, and narcissism’s facet structure. Appl Psychol 64(1):93–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12025

Grijalva E, Zhang L (2016) Narcissism and self-insight: a review and meta-analysis of narcissists’ self-enhancement tendencies. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 42(1):3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636

Harari MB, Manapragada A, Viswesvaran C (2017) Who thinks they’re a big fish in a small pond and why does it matter? A meta-analysis of perceived overqualification. J Vocat Behav 102:28–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.06.002

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York, NY

Heintzelman SJ, King LA (2013) On knowing more than we can tell: intuitive processes and the experience of meaning. J Posit Psychol 8(6):471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.830758

Helfrich H, Dietl E (2019) Is employee narcissism always toxic? – The role of narcissistic admiration, rivalry and leaders’ implicit followership theories for employee voice. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 28(2):259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1575365

Higgs M (2009) The good, the bad and the ugly: leadership and narcissism. J Change Manag 9(2):165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879111

Huang Y, Hu Y (2022) A moderated mediating model of perceived overqualification and task i-deals – roles of prove goal orientation and climate for inclusion. Chin Manag Stud 16(2):382–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-10-2020-0453

Jalan I (2020) Treason or reason? Psychoanalytical insights on whistleblowing. Int J Manag Rev 22(3):249–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12224

Johnson GJ, Johnson WR (2000) Perceived overqualification and dimensions of job satisfaction: a longitudinal analysis. J Psychol 134(5):537–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980009598235

Jonason PK, Wee S, Li NP (2014) Thinking bigger and better about “bad apples”: evolutionary industrial–organizational psychology and the dark triad. Ind Organ Psychol 7(1):117–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12118

Judge TA, LePine JA, Rich BL (2006) Loving yourself abundantly: relationship of the narcissistic personality to self- and other perceptions of workplace deviance, leadership, and task and contextual performance. J Appl Psychol 91(4):762–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.762

Khan A, Chaudhary R (2022) Gossip at work: a model of narcissism, core self-evaluation and perceived organizational politics. Int J Manpow 44(2):197–213. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-09-2021-0559

Konrath S, Ho MH, Zarins S (2016) The strategic helper: narcissism and prosocial motives and behaviors. Curr Psychol 35(2):182–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9417-3

LeBreton JM, Shiverdecker LK, Grimaldi EM (2018) The dark triad and workplace behavior. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 5(1):387–414. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104451

LePine JA, Van Dyne L (1998) Predicting voice behavior in work groups. J Appl Psychol 83(6):853–868. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.6.853

LePine JA, Van Dyne L (2001) Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol 86(2):326–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.326

Li C, Sun Y, Ho MY et al. (2016) State narcissism and aggression: the mediating roles of anger and hostile attributional bias. Aggress Behav 42(4):333–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21629

Lin B, Law KS, Zhou J (2017) Why is underemployment related to creativity and OCB? A task-crafting explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations. Acad Manage J 60(1):156–177

Lin X, Wu C-H, Dong Y et al. (2022) Psychological contract breach and destructive voice: the mediating effect of relative deprivation and the moderating effect of leader emotional support. J Vocat Behav 135:103720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103720

Liu J, Lee C, Hui C, Kwan HK, Wu L-Z (2013) Idiosyncratic deals and employee outcomes: the mediating roles of social exchange and self-enhancement and the moderating role of individualism. J Appl Psychol 98(5):832–840. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032571

Liu X, Mao J-Y, Zheng X, Ni D, Harms PD (2022) When and why narcissism leads to taking charge? The roles of coworker narcissism and employee comparative identity. J Occup Organ Psychol 95(4):758–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12401

Lobbestael J, Baumeister RF, Fiebig T, Eckel LA (2014) The role of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in self-reported and laboratory aggression and testosterone reactivity. Pers Individ Differ 69:22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.007

Lobene EV, Meade AW, Pond SB (2015) Perceived overqualification: a multi-source investigation of psychological predisposition and contextual triggers. J Psychol 149(7):684–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.967654

Luksyte A, Spitzmueller C, Maynard DC (2011) Why do overqualified incumbents deviate? Examining multiple mediators. J Occup Health Psychol 16(3):279–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022709

Ma C, Lin X, Chen ZX, Wei W (2020) Linking perceived overqualification with task performance and proactivity? An examination from self-concept-based perspective. J Bus Res 118:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.041

Mackey JD, Huang L, He W (2020) You abuse and I criticize: an ego depletion and leader–member exchange examination of abusive supervision and destructive voice. J Bus Ethics 164(3):579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4024-x

Martinsen ØL, Arnulf JK, Furnham A, Lang-Ree OC (2019) Narcissism and creativity. Pers Individ Differ 142:166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.032

Maynard DC, Brondolo EM, Connelly CE, Sauer CE (2015) I’m too good for this job: narcissism’s role in the experience of overqualification. Appl Psychol Int Rev 64(1):208–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12031

Maynard DC, Joseph TA, Maynard AM (2006) Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. J Organ Behav 27(4):509–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.389

Maynes TD, Podsakoff PM (2014) Speaking more broadly: an examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behaviors. J Appl Psychol 99(1):87–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034284

Moorman RH, Harland LK (2002) Temporary employees as good citizens: factors influencing their OCB performance. J Bus Psychol 17(2):171–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019629330766

Morrison EW (2011) Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research. Acad Manag Ann 5(1):373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506

Ng TWH, Feldman DC (2012) Employee voice behavior: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J Organ Behav 33(2):216–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.754

Ng TWH, Hsu DY, Parker SK (2021) Received Respect and constructive voice: the roles of proactive motivation and perspective taking. J Manag 47(2):399–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063198346

O’Reilly CA, Chatman JA (2020) Transformational leader or narcissist? How grandiose narcissists can create and destroy organizations and institutions. Calif. Manag Rev 62(3):5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/000812562091498

Penney LM, Spector PE (2002) Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior: do bigger egos mean bigger problems? Int J Sel Assess 10(1–2):126–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00199

Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR (2010) Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6(1):421–446. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131215

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Pratt MG, Foreman PO (2000) Classifying managerial responses to multiple organizational identities. Acad Manag Rev 25(1):18–42. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791601

Reina CS, Zhang Z, Peterson SJ (2014) CEO grandiose narcissism and firm performance: the role of organizational identification. Leadersh Q 25(5):958–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.06.004

Resick CJ, Whitman DS, Weingarden SM, Hiller NJ (2009) The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. J Appl Psychol 94(6):1365–1381. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016238

Riketta M, Dick RV (2005) Foci of attachment in organizations: a meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. J Vocat Behav 67(3):490–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.06.001

Roczniewska M, Bakker AB (2016) Who seeks job resources, and who avoids job demands? The link between dark personality traits and job crafting. J Psychol 150(8):1026–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1235537

Sedikides C, Ntoumanis N, Sheldon KM (2019) I am the chosen one: narcissism in the backdrop of self-determination theory. J Pers 87(1):70–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12402

Shah M, Sarfraz M, Khawaja KF, Tariq J (2020) Does narcissism encourage unethical pro-organizational behavior in the service sector? A case study in Pakistan. Glob Bus Organ Excell 40(1):44–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22062

Smidts A, Pruyn ATH, Riel CBMV (2001) The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad Manag J 44(5):1051–1062. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069448

Smith MB, Webster BD (2018) Narcissus the innovator? The relationship between grandiose narcissism, innovation, and adaptability. Pers Individ Differ 121:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.018

Spurk D, Keller AC, Hirschi A (2016) Do bad guys get ahead or fall behind? Relationships of the dark triad of personality with objective and subjective career success. Soc Psychol Pers Sci 7(2):113–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615609735

Strauss K, Parker SK (2018) Intervening to enhance proactivity in organizations: improving the present or changing the future. J Manag 44(3):1250–1278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315602531

Swann WB, Stein-Seroussi A, Giesler RB (1992) Why people self-verify. J Pers Soc Psychol 62(3):392–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.3.392

Tornau K, Frese M (2013) Construct clean-up in proactivity research: a meta-analysis on the nomological net of work-related proactivity concepts and their incremental validities. Appl Psychol. Int Rev 62(1):44–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00514.x

Turner JC, Brown RJ, Tajfel H (1979) Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur J Soc Psychol 9(2):187–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420090207

Twenge JM, Foster JD (2010) Birth cohort increases in narcissistic personality traits among American college students, 1982–2009. Soc Psychol Pers Sci 1(1):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550609355719

Wallace HM, Baumeister RF (2002) The performance of narcissists rises and falls with perceived opportunity for glory. J Pers Soc Psychol 82(5):819–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.819

Walumbwa FO, Schaubroeck J (2009) Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J Appl Psychol 94(5):1275–1286. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015848

Webster BD, Smith MB (2019) The dark triad and organizational citizenship behaviors: the moderating role of high involvement management climate. J Bus Psychol 34(5):621–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9562-9

Witte TH, Callahan KL, Perez-Lopez M (2002) Narcissism and anger: an exploration of underlying correlates. Psychol Rep 90(3):871–875. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3.87

Xia Y, Xu Y, Wu C (2019) The curvilinear relationship between perceived overqualification and employee voice. Acad Manag Annu Meet Proc 2019(1):17234. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.17234abstract

Zagenczyk TJ, Smallfield J, Scott KL, Galloway B, Purvis RL (2017) The Moderating Effect of Psychological Contract Violation on the Relationship between Narcissism and Outcomes: An Application of Trait Activation Theory. Front Psychol 8:1113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01113

Zeigler-Hill V, Besser A (2013) A glimpse behind the mask: facets of narcissism and feelings of self-worth. J Pers Assess 95(3):249–260

Zhang H, Ou AY, Tsui AS, Wang H (2017) CEO humility, narcissism and firm innovation: a paradox perspective on CEO traits. Leadersh Q 28(5):585–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.003

Zhang J, Akhtar MN, Zhang Y, Sun S (2020) Are overqualified employees bad apples? A dual-pathway model of cyberloafing. Internet Res 30(1):289–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-10-2018-0469

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZC contributed to study conception theoretical foundation, model development, research design, literature research, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of ethics committee of Jilin University of Finance and Economics and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Z. Good soldiers or bad apples? Exploring the impact of employee narcissism on constructive and destructive voice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02230-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02230-8

- Springer Nature Limited