Abstract

This study examines sex differences regarding social skills, behavior problems and bullying engagement, and the association of social skills and behavior problems with bullying engagement, in adolescents. Participants were 447 Portuguese adolescents (252 girls and 195 boys) aged between 12 and 19-years-old. Social skills and behavior problems were assessed using the self-report version of Social Skills Improvement System – Rating Scales. Bullying engagement was assessed using the Scale of Interpersonal Behavior at School. Girls scored higher on social skills and reported more internalizing and fewer externalizing problems than boys, whereas boys reported more aggressive verbal behaviors than girls. Adolescents exhibiting fewer social skills and more internalizing and externalizing problems engage more frequently in bullying aggressive behaviors. In addition, adolescents presenting more internalizing and externalizing problems are more often victimized by bullies. Furthermore, boys more frequently engage in bullying aggressive and victimization behaviors, whereas younger adolescents with more social skills tend to engage less frequently in bullying aggressive behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The complexity of relationships established in school often leads to conflicts that can escalate to violence, causing fear and insecurity when interacting with peers (Bashir et al., 2020). These conflicts tend to occur more frequently during adolescence, as profound changes in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains occur during this developmental stage (Darjan et al., 2020; Deniz & Ersoy, 2016). These changes are frequently associated with difficulties when engaging with peers’ interactions (Gonzalez et al., 2009; Janssen et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2018; Sentse et al., 2016).

Bullying is probably one of the most common examples of these conflicts, which often escalate to violence at school. In this study, bullying is defined according to Olweus (1993, 1999) proposal in which being bullied or victimized is associated with the exposition, repeatedly and over time, to negative or aggressive actions on the part of one or more other peers. According to the author, bullying requires an imbalance of power or strength that leads victims to feel weak or unable to defend themselves. Therefore, bullying refers to aggressive behaviors that are repeated, intentional, and intended to cause harm to other/s, over an extended period in a context of observable and/or perceived power inequity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019; Olweus, 2013; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Swearer & Hymel, 2015; Volk et al., 2014). These acts of aggression are a strategy of social affirmation, as they allow to conquer, or maintain, a privileged position within the peers’ group (Smith et al., 2019; Volk et al., 2014).

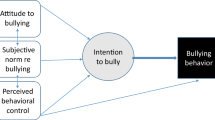

Bullying is a public health concern (Cho & Lee, 2018; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016), due to its strong negative impact on physical and mental health (Tsitsika et al., 2014). Given the inevitably health, educational, social, and political implications of bullying, it becomes relevant to understand more deeply the factors underlying this phenomenon. Evidence has yielded that psychosocial risk factors, such as internalizing or externalizing problems and difficulties in social skills, may contribute differently to adolescents’ engagement in bullying, as aggressors or victims (Jankauskiene et al., 2008; Marini et al., 2006). A wide body of research shows that difficulties in social skills (e.g., empathy, cooperation, or self-control) are associated with bullying engagement (Jenkins et al., 2014; Horne & Socherman, 1996; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015; Perren & Alsaker, 2006; Rupp et al., 2018; Sterzing et al., 2012; Unnever & Cornell, 2003). Hence, the current study aimed to examine the association of sex, social skills, and behavior problems in the engagement in bullying behaviors, based on the model of social skills proposed by Gresham and Elliott (1984, Gresham & Elliott, 1990; Gresham et al., 2011). It also aimed to contribute to develop interventions that, in a promotional, preventive or remediation way, may help to prevent and reduce internalizing and externalizing problems, as precursors of psychopathology, as well as to promote social skills, to diminish the impact of bullying and their negative effects on the relationships established with peers and adults at school.

The phenomenon of bullying

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2019a), there are four main types of bullying: 1) physical, 2) psychological, 3) sexual, and 4) cyberbullying. Physical bullying consists of persistent aggressions, such as being hit, hurt, kicked, pushed, shoved around or locked indoors, having personal belongings being stolen, taken or destroyed, and/or being coerced to do things. Psychological bullying comprises verbal and emotional abuse, being intentionally excluded or ignored, as well as being insulted, teased and/or subject of lies or nasty rumors. Sexual bullying includes being made fun of with sexual jokes, comments, or gestures. Cyberbullying refers to being bullied through messages, being treated in a hurtful or cruel way by mobile phones (i.e., texts, calls, video clips) or online (i.e., email, instant messaging, social networking, chatrooms). Recent evidence shows that the traditional forms of bullying (e.g., physical or psychological) are still more common than cyberbullying (Feijóo et al., 2021). Overall, bullying is not limited to direct physical or verbal aggression, but it also includes indirect forms of aggression. Furthermore, in addition to direct interaction between bullies and victims, bullying also involves the indirect engagement, or observation, of aggressive behaviors (Fekkes et al., 2005; Tsang et al., 2011; Zych et al., 2017).

Bullying has a high incidence in schools worldwide. One in three students (32%) reported being bullied by their peers at school, at least once in the last month (UNESCO, 2019a). In Portuguese schools, bullying is also widespread (Mira et al., 2017), with a mean prevalence of 39% of children and adolescents reporting having been bullied, at least once in the last month (UNESCO, 2019b). Boys perpetrate more physical bullying compared to girls (Stubbs-Richardson et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2019), whereas girls report to be more victimized in typical bullying (Zsila et al., 2019). These differences may be related to distinct social skills competences (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2019), as well as the presence of internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Košir et al., 2020), which may justify the distinct role of boys and girls when engaging in bullying.

Social skills, behavior problems and bullying engagement

Difficulties in social skills (e.g., empathy or cooperation) (Langeveld et al., 2012; Rupp et al., 2018) and behavior problems, such as internalizing (e.g., anxiety/depressive states or somatic complains) and externalizing problems (e.g., aggression or hyperactivity), are among the risk factors that contribute to the maintenance and aggravation of bullying experiences (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017; Méndez et al., 2017; Olweus & Limber, 2010; Zych et al., 2020a).

Social skills refer to interpersonal behaviors that result in acceptable and positive responses and avoid negative reactions in social interactions, such as cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, self-control, communication (Gresham & Elliott, 1984, Gresham & Elliott, 1990; Gresham et al., 2011). Several studies show that difficulties in social skills are related to bullying engagement (Jenkins et al., 2014; Horne & Socherman, 1996; Perren & Alsaker, 2006; Rupp et al., 2018; Sterzing et al., 2012). Bullies, mostly boys than girls, tend to exhibit higher levels of assertiveness and lower levels of empathy, cooperation and self-control, which explains their aggressiveness, impulsivity, and the assumption of superiority attitudes when interacting with their peers (Jenkins et al., 2014; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015; Unnever & Cornell, 2003; Wang et al., 2012). In contrast, bullying victims, frequently girls, are more likely to exhibit difficulties in cooperation, assertiveness, empathy and self-control (Champion et al., 2003; Egan & Perry, 1998; Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012; Jenkins et al., 2014), which contributes to their vulnerability in social interactions with their peers.

Internalizing and externalizing problems are also associated with engaging in bullying (Garcia-Continente et al., 2013; Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019; Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017; Ledwell & King, 2013; Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

Internalizing problems are related to inappropriate or maladjusted control of emotions and cognitions. These are defined by the presence of anxiety/depression symptoms, withdrawn, or somatic complaints (Achenbach, 1966, 1991; Arslan et al., 2020). Internalizing difficulties are mainly predictive of victimization behaviors, particularly in girls (Casper & Card, 2016; Cosma et al., 2018; Zych et al., 2020a). Victims of bullying often present depressive (Klomek et. al, 2019; Lemstra et al., 2012; Skarstein et al., 2020) and anxiety symptoms (Price et al., 2013), as well as suicidal ideation (Holt et al., 2015; Klomek et al., 2018; Massing-schaffer et al., 2018). Interestingly, bullies are also more likely to present internalizing symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (Azevedo da Silva et al., 2019; Garcia-Continente et al., 2013).

In contrast, externalizing problems refer to behaviors that reflect a negative impact on the environment (Campbell et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 2001). Often, externalizing difficulties are characterized by the presence of disruptive and/or aggressive behaviors (Achenbach, 1966, 1991; Arslan et al., 2020). Externalizing problems are also strongly connected to bullying engagement (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017). Bullies often exhibit disruptive and antisocial behaviors, such as alcohol and substance abuse, which is more commonly observed among boys (Casper & Card, 2016; Garcia-Continente et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2019). In addition, adolescents with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) tend to show difficulties in reading social cues and managing conflicts that frequently leads them to engage in bullying, both as bullies and as victims (Busch et al., 2015; Horne & Socherman, 1996; Jenkins et al., 2014; Perren & Alsaker, 2006; Rupp et al., 2018; Sterzing et al., 2012). Therefore, more than specific vulnerabilities, bullies tend to exhibit more socioemotional adjustment problems that can lead to the emergence and development of psychopathology.

Study purpose

Studies have previously investigated the association of social skills, behavior problems, and the engagement in bullying (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2019; Garcia-Continente et al., 2013; Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, evidence of the effects of sex, age, social skills and behavior problems is lacking. To address this gap, this study aimed to examine: 1) sex differences regarding social skills, behavior problems, and bullying engagement, and 2) the association of sex, age, social skills and behavior problems with bullying engagement, among Portuguese adolescents. We expect boys to exhibit fewer social skills, as well as more externalizing and fewer internalizing problems, when compared to girls. We also expect both social skills and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems to be associated with bullying engagement, namely: 1) lower social skills are associated with increased engagement in bullying, both as aggressors and victims, 2) more externalizing and internalizing problems to be associated with increased engagement in bullying, specifically in aggressive behaviors, and 3) more internalizing problems to be associated with increased engagement in bullying as victims.

Method

Participants

Participants were 447 adolescents (252 girls and 195 boys) aged between 12 and 19-years-old (M = 14.71; SD = 1.42), attending schools in Porto district, Portugal. Although convenience sampling was used, efforts to ensure some geographical and social diversity and representativeness were made in the definition of inclusion criteria. Therefore, schools located in rural or semi-rural areas and mostly attended by children and adolescents from low and middle-income families were selected.

Of the 447 adolescents enrolled in this study, 160 (35.8%) attended the 9th grade, 122 (27.3%) the 8th grade, 68 (15.2%) the 11th grade, 58 (13.0%) the 10th grade, and 36 (8.1%) the 12th grade. Boys were aged between 12 and 19-years-old (M = 14.82; SD = 1.42), with 75 (38.5%) attending the 9th grade, 53 (27.2%) the 8th grade, 28 (14.4%) the 11th grade, 25 (12.8%) the 10th grade, and 14 (7.2%) the 12th grade. Girls were aged between 12 and 18-years-old (M = 14.63; SD = 1.41), with 85 (34.1%) attending the 9th grade, 69 (27.7%) the 8th grade, 40 (16.1%) the 11th grade, 33 (13.3%) the 10th grade, and 22 (8.8%) the 12th grade.

Adolescents with cognitive difficulties, identified by teachers, were not included in this study, as they were not able to autonomously complete the questionnaires.

Measures

Sociodemographic information

Adolescents were asked to fill a sociodemographic questionnaire to gather information on age, sex, school grade and the city of residence.

Social skills and behavior problems

To assess social skills and behavior problems, the self-report version of Social Skills Improvement System – Rating Scales (SSIS-RS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008; Barbosa-Ducharne et al., 2012) was used. SSIS-RS comprises 75 items, assessed in a 4-point Likert-scale (from 0 – never/almost never to 3 – almost always/always). It includes two scales: social skills and behavior problems, each of them comprising a set of subscales.

The social skills scale consists of 46 items, organized in seven subscales: Communication (e.g., I say ‘please’ when I ask for something.), Assertiveness (i.e., I defend those who are not treated well by others.), Responsibility (e.g., I do what is correct without being told.), Cooperation (e.g., I do what teachers ask me to do.), Empathy (e.g., I try to think how the other people feel.), Engagement (e.g., I make friends easily.) and Self-Control (e.g., I stay calm.).

The behavior problems scale is composed of 29 items, organized in four subscales: Externalization (e.g., I swear.), Bullying (e.g., I do not allow others to join my group of friends.), Hyperactivity/Attention Deficit (e.g., I have difficulties in being quiet.) and Internalization (e.g., I feel ashamed easily.). The sum of the scores of the items of each subscale allows to obtain the total score for Social Skills and Behavior Problems scales.

For this study purpose, only three subscales were considered – social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems. Good to excellent internal consistency results were observed for the scales social skills (α = .94), internalization (α = .77) and externalization (α = .82).

Bullying engagement

To assess bullying engagement, both as an aggressor or as a victim, the Scale of Interpersonal Behavior at School was used (SIBS; Almeida, 2013). This questionnaire includes 22 items, assessed in a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = never happens to 4 = it happens quite often). These items describe bullying behaviors, including aggression and victimization, and are organized in four scales: Verbal Aggression, Indirect Aggression, Verbal Victimization and Indirect Victimization. Verbal Aggression comprises items concerning verbal aggression within peers’ interactions (e.g., I tease my colleagues.). Indirect Aggression includes three items related to aggressive behaviors, leading to the victims’ withdrawn and intimidation (e.g., I damage my colleagues’ things.). Verbal Victimization consists of four items referring to threats and verbal intimidation (e.g., My colleagues call me names that I don’t like.). Indirect Victimization consists of three items describing interactions in which the adolescent is intentionally isolated from the group, threatened or intimidated by their peers (e.g., ‘My colleagues do not allow me to participate in activities.). The sum of the items of each scale allows to obtain its total score. In this study, acceptable to good internal consistency results were observed for Verbal Aggression (α = .78), Indirect Aggression (α = .83), Verbal Victimization (α = .86) and Indirect Victimization (α = .69).

Procedure

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliation institution. Participants were recruited from schools in Porto district, Portugal, by contacting the schools and inviting them to participate. The directors interested in participating were provided with a document explaining the study goals, instruments, and procedures of the study, as well as ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of the data collected. In addition, school directors were asked to select a teacher, or a group of teachers, to mediate communication with adolescents.

The data collection occurred between October 2020 and June 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the questionnaires were completed on-line, through the Google Forms platform, in the classroom, under the supervision of the teachers. Of note, teachers did not have access to the adolescents’ answered questionnaires. The link to complete the questionnaires was forwarded by e-mail to the school directors, who then sent it to the teacher/s previously selected. Study goals, instruments and required procedures, as well as ethical issues, were presented to the adolescents by the teachers, at the classroom. After this presentation, adolescents were asked to give their parents, or alternative legal representatives or guardians, an informed consent. Teachers sent this link to the adolescents whose parents had given informed consent to participate in the study and who volunteered to be enrolled.

The administration took, approximately, 15 to 20 minutes to complete.

Data analyses

Data were processed and analyzed using the software IBM® SPSS version 27.0. Pearson correlation coefficients have been computed for all variables, and normality assumption (skewness and kurtosis values) was examined. Then, Descriptive analyzes were conducted to characterize the sample and determine means, standard-deviations, medians, and ranges for all variables aggressive and victimization behaviors studied (social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems and bullying engagement – verbal and indirect). Multivariate and univariate analyzes of variance were then conducted to determine sex differences regarding all variables in the study. The assumptions for the multivariate and univariate analyses were all met, with normality distribution, equality of variance, and univariate outliers checked, with only small deviation form normality found (Field, 2018). Homogeneity of variance was assessed through Levene’s test (p < .05), which was confirmed. Finally, a set of multiple regression analyses, with enter method, were conducted to test the association of age, sex, social skills, and internalizing and externalizing problems, and interaction terms between sex and social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems, and between age and social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems to test the association between those interactions with bullying engagement, as a victim and as an aggressor, separately. The assumptions for the regression analyses were all met (Field, 2018). First, a standard residual analysis was performed to identify any outliers. This confirmed that the data did not contain any outliers (Std. Residual Min = -2.36, Std. Residual Max = 2.08). Tests to determine if the data met the assumption of collinearity indicated that multicollinearity was not a problem in any of the models tested (tolerance values ranged from .89 to .99; VIF ranged from 1.02 to 1.12). The data also met the assumption of independent errors (Durbin-Watson values = 1.85, 1.87). The histograms of the standardized residuals indicated that the data contained approximately normally distributed errors, which was confirmed by the normal P-P plots of the standardized residuals, and the scatter plots of the standardised residuals showed that the data met the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity. For interaction effects, variables were centered to minimize collinearity.

Results

Table 1 reports Pearson coefficient correlations between all variables in study – social skills, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, bullying victimization behaviors, and bullying aggressive behaviors. In addition, skewness and kurtosis values are also presented for examining normality assumption.

Social skills, behavior problems and bullying engagement

Table 2 depicts the means, standard-deviations, medians, and ranges for the total sample, and for boys and girls separately, concerning social skills, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems, and bullying engagement.

Results indicated that girls reported greater social skills than boys. Likewise, they scored higher in internalizing behaviors, compared to boys. Contrarily, boys scored higher in externalizing behaviors, compared to girls. Regarding bullying engagement, boys reported more involvement in aggression behaviors, while girls reported more involvement in victimization behaviors.

Sex effect on social skills, behavior problems and bullying engagement

To assess the effect of sex on social skills, a univariate analyze of variance was performed with social skills as the dependent variable. A significant main effect was found for sex, F(1, 446) = 12.70, p < .001, η2 = .028. Girls (M = 99.40, SE = 1.27, CI 95% 66.91 – 101.91) scored higher in social skills compared to boys (M = 92.55, SE = 1.44 CI 95% 89.72 – 95.40).

To examine the effect of sex on behavior problems scale, a univariate analyze of variance was performed with behavior problems defined as the dependent variable. No significant main effect was observed for sex, F(1, 446) = 1.11, p = .292, η2 = .002. To assess the effect of sex on internalizing and externalizing problems, a multivariate analyze of variance was conducted, where internalizing and externalizing problems were defined as the dependent variables. A significant main effect was found for sex, F(2, 444) = 29.97, p < .001, η2 = .119, particularly a significant effect for internalizing problems, F(1, 446) = 31.94, p < .001, η2 = .067. Girls (M = 12.39, SE = 0.36, CI 95% 11.69 – 13.09) reported more internalizing problems compared to boys (M = 9.34, SE = 0.41, CI 95% 8.54 – 10.13). Also, results indicated a significant effect for externalizing problems, F(1, 446) = 7.63, p = .006, η2 = .017. Contrarily, boys (M = 9.02, SE = 0.41, CI 95% 8.23 – 9.82) reported more externalizing problems compared to girls (M = 7.53, SE = 0.36 CI 95% 6.83 – 8.23).

To assess the main effect of sex on bullying engagement (aggression and victimization), a multivariate analyze of variance was performed with aggressive behaviors and victimization behaviors defined as the dependent variables. A significant main effect was observed for sex, F(2, 444) = 5.93, p = .003, η2 = .026. Results indicated a significant effect for aggressive behaviors, F(1, 446) = 6.22, p = .013, η2 = .014, with boys (M = 8.70, SE = 0.18, CI 95% 8.34 – 9.06) reporting engaging in more bullying aggressive behaviors than to girls (M = 8.09, SE = 0.16, CI 95% 7.78 – 8.41). A nonsignificant effect was verified for victimization behaviors, F(1, 446) = 0.28, p = .597, η2 = .001.

A multivariate analyze of variance was performed with verbal aggression behaviors, indirect aggression behaviors, verbal victimization behaviors, and indirect victimization behaviors defined as the dependent variables. A significant main effect was found for sex, F(4, 442) = 3.81, p = .005, η2 = .033. Results revealed a significant main effect for verbal aggression behaviors F(1, 446) = 8.71, p = .003, η2 = .019, where boys (M = 5.43, SE = 0.13, CI 95% 5.17 – 5.69) scored higher compared to girls (M = 4.90, SE = 0.12, CI 95% 4.68 – 5.13). Nonsignificant effects were found for indirect aggressive behaviors, F(1, 446) = 0.90, p = .344, η2 = .002, verbal victimization behaviors, F(1, 446) = 0.34, p = .563, η2 = .001, and indirect victimization behaviors, F(1, 446) = 0.10, p = .751, η2 < .001.

Interaction of sex and social skills and behavior problems, and its association with bullying aggressive behaviors

To assess the association between sex, social skills and the interaction of sex and social skills with bullying aggressive behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was performed with sex, social skills, and the interaction term ‘sex X social skills’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. Results are illustrated in Table 3. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by sex and social skills was 3.9% (adjusted R2 = .04, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and social skills (β = -.17, p < .001), but not between bullying aggressive behaviors and sex (β = .09, p = .061). For the interaction term ‘sex X social skills’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .741).

Likewise, the association between sex, internalizing problems and the interaction of sex and internalizing problems with bullying aggressive behaviors was assessed by a multiple regression analysis with enter method with sex, internalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘sex X internalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by sex and internalizing problems was 5.2% (adjusted R2 = .05, p < .001). As reported at Table 3, statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and internalizing problems (β = -.21, p < .001), and between bullying aggressive behaviors and sex (β = .17, p < .001). For the interaction term ‘sex X internalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .120).

Finally, for assessing the association between sex, externalizing problems and the interaction of sex and externalizing problems with bullying aggressive behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was conducted with sex, externalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘sex X externalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by sex and externalizing problems was 23.4% (adjusted R2 = .23, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and externalizing problems (β = .48, p < .001), but not between bullying aggressive behaviors and sex (β = .06, p = .185). For the interaction term ‘sex X externalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .994) (see Table 3).

Interaction of sex and social skills and behavior problems, and its association with bullying victimization behaviors

To assess the association between sex, social skills and the interaction of sex and social skills with bullying victimization behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was performed with sex, social skills, and the interaction term ‘sex X social skills’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. Results are illustrated in Table 4. The regression models were not statistically significant (p = .091 and p = .989).

Likewise, for assessing the association between sex, internalizing problems and the interaction of sex and internalizing problems with bullying victimization behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was conducted with sex, internalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘sex X internalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying victimization behaviors explained by sex and internalizing problems was 17.5% (adjusted R2 = .18, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying victimization behaviors and internalizing problems (β = .44, p < .001), and between bullying victimization behaviors and sex (β = .09, p = .049). For the interaction term ‘sex X internalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .852) (see Table 4).

Finally, the association between sex, externalizing problems and the interaction of sex and externalizing problems with bullying victimization behaviors was assessed by a multiple regression analysis with enter method with sex, externalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘sex X externalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying victimization behaviors explained by sex and externalizing problems was 13.9% (adjusted R2 = .14, p < .001). As reported in Table 4, statistically significant associations were found between bullying victimization behaviors and externalizing problems (β = .38, p < .001), but not between bullying victimization behaviors and sex (β = .17, p < .001). For the interaction term ‘sex X externalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .210).

Interaction of age and social skills and behavior problems, and its association with bullying aggressive behaviors

To assess the association between age, social skills and the interaction of age and social skills with bullying aggressive behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was performed with age, social skills, and the interaction term ‘age X social skills’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. Results are illustrated in Table 5. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by age and social skills was 3.1% (adjusted R2 = .03, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and social skills (β = -.19, p < .001), but not between bullying aggressive behaviors and age (β = .02, p = .674). For the interaction term ‘age X social skills’, the regression model was statistically significant and explained 3.8% of the variance of bullying aggressive behaviors (p = .048). The interaction between age and social skills, in association with bullying aggressive behaviors is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Likewise, the association between age, internalizing problems and the interaction of age and internalizing problems with bullying aggressive behaviors was assessed by a multiple regression analysis with enter method with age, internalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘age X internalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by age and internalizing problems was 2.5% (adjusted R2 = .03, p = .001). As reported in Table 5, statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and internalizing problems (β = .17, p < .001), but not between bullying aggressive behaviors and age (β = .02, p = .692). For the interaction term ‘age X internalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .216).

Finally, to assess the association between age, externalizing problems and the interaction of age and externalizing problems with bullying aggressive behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was conducted with age, externalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘age X externalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying aggressive behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying aggressive behaviors explained by age and externalizing problems was 23.1% (adjusted R2 = .23, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying aggressive behaviors and externalizing problems (β = .49, p < .001), but not between bullying aggressive behaviors and age (β = -.02, p = .655). For the interaction term ‘age X externalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .693) (see Table 5).

Interaction of age and social skills and behavior problems, and its association with bullying victimization behaviors

To assess the association between age, social skills and the interaction of age and social skills with bullying victimization behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was performed with age, social skills, and the interaction term ‘age X social skills’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. Results are illustrated in Table 6. The regression models were not statistically significant (p = .061 and p = .272).

Likewise, for assessing the association between age, internalizing problems and the interaction of age and internalizing problems with bullying victimization behaviors, a multiple regression analysis with enter method was conducted with age, internalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘age X internalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying victimization behaviors explained by age and internalizing problems was 17.1% (adjusted R2 = .17, p < .001). Statistically significant associations were found between bullying victimization behaviors and internalizing problems (β = .41, p < .001), but not between bullying victimization behaviors and age (β = -.06, p = .189). For the interaction term ‘age X internalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .886) (see Table 6).

Finally, the association between age, externalizing problems and the interaction of age and externalizing problems with bullying victimization behaviors was assessed by a multiple regression analysis with enter method with age, externalizing problems, and the interaction term ‘age X externalizing problems’ as independent variables, and bullying victimization behaviors as dependent variable. The variance of bullying victimization behaviors explained by age and externalizing problems was 14.1% (adjusted R2 = .14, p < .001). As observed in Table 6, statistically significant associations were found between bullying victimization behaviors and externalizing problems (β = .38, p < .001), but not between bullying victimization behaviors and age (β = -.09, p = .009). For the interaction term ‘age X externalizing problems’, the regression model was not statistically significant (p = .632).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of sex, age, social skills, behavior problems (particularly externalizing and internalizing problems) on bullying engagement. In addition, it aimed to investigate the association of social skills and internalizing and externalizing problems with bullying engagement, as aggressors and as victims, among Portuguese adolescents.

Regarding sex differences, as expected, girls exhibited more social skills and more internalizing problems and fewer externalizing problems than boys. Sex differences in social skills and behavior problems have been widely documented in the literature, as several studies show that girls tend to read and respond more accurately to social interactions (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2019; Keane & Calkins, 2004; Tan et al., 2018). They also tend to exhibit more internalizing problems and fewer externalizing problems, when compared to boys (Achenbach et al., 2016; Huaqing Qi & Kaiser, 2003; Kramer et al., 2007; Rosenfield, 2000).

In addition, results show that boys exhibit more aggressive behaviors, particularly verbal aggression, than girls. This in line with the existing research showing that aggressive behaviors are more commonly observed and reported by boys than girls (Björkqvist, 2018; Card et al., 2008; Casper & Card, 2016). These results add to the evidence that boys tend to exhibit more aggressive behaviors compared to girls (Björkqvist, 2018; Card et al., 2008; Casper & Card, 2016). This may be explained by the fact that boys tend to exhibit increased levels of arousal, during infancy, and less inhibitory control, in early childhood (Chaplin, 2015). This may be related to cultural beliefs on gender differences in children’s expression of emotion. Boys are expected to be strong, not to cry and to show anger, when necessary, while girls are usually expected to express sadness, compassion or cheeriness (Chaplin & Aldao, 2013). These differences may also be due to the increased levels of externalizing problems typically observed in boys (Achenbach et al., 2016; Kramer et al., 2007). Externalizing problems tend to be associated with difficulties in internalizing socio-moral rules, norms, and conventions, in reading social cues, as well as with poor emotion regulation skills (Hukkelberg et al., 2019). Therefore, adolescents with externalizing problems may possibly tend to perceive social situations as threatening, leading them to respond with impulsive and aggressive behaviors (Van Rest et al., 2020).

In contrast to what has been observed with aggression, no differences were found in bullying victimization behaviors. Evidence on these differences is ambiguous. Some studies show that boys are more likely to be victims of bullying than girls (Méndez et al., 2017), while others observe the opposite (Pontes et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2017). It is possible that this contradictory evidence is better explained by other variable other than sex. Being a victim of bullying often generates shame, embarrassment, and fear of reprisal, which may lead victims to not report the aggression they suffered (Romera et al., 2019). Additionally, evidence suggests that victimization experiences are related to increased depressive symptoms, which are commonly associated with higher levels of body image shame and severe self-criticism (Duarte et al., 2015). According to the authors, this may lead adolescents to blame themselves for being bullied, to legitimize aggressions and avoid public exposure. Hence, the number of reported aggressions by victims may not reflect the real incidence of the phenomenon.

Regarding bullying engagement, results of the multiple regression showed that i) engaging in aggressive behaviors is associated with social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as with adolescents’ sex; and ii) engaging in victimization behaviors is associated both with internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as with adolescents’ sex and age. In addition, an association of the interaction between social skills and age with bullying aggressive behaviors was observed.

Adolescents presenting fewer social skills and more internalizing and externalizing problems are more often engaged in bullying aggressive behaviors. Additionally, adolescents showing more internalizing and externalizing problems are more often victims of bullying. Furthermore, boys are more frequently engaged in bullying aggressive and victimization behaviors; and younger adolescents with more social skills tend to engage less frequently in bullying aggressive behaviors. Importantly, small and medium effect sizes were observed for these associations, which requires a careful interpretation of these findings, as other variables which were not included in the analyses may also explain the variance observed in the engagement in bullying behaviors.

The association of poor social skills with bullying aggressive behaviors engagement has been widely reported, as a maladaptive assertiveness use and lower levels of empathy, cooperation, and self-control often lead to aggressiveness, impulsivity, and the assumption of superiority attitudes when interacting with peers (Jenkins et al., 2014; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015; Unnever & Cornell, 2003; Wang et al., 2012).

Likewise, evidence seems consistent in reporting that adolescents who present more internalizing and externalizing problems are also more likely to engage in aggressive behaviors (Azevedo da Silva et al., 2019; Busch et al., 2015; Casper & Card, 2016; Garcia-Continente et al., 2013; Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017; Richard et al., 2019). Research shows that adolescents who engage in bullying aggressive behaviors often present internalizing symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (Azevedo da Silva et al., 2019; Garcia-Continente et al., 2013).

The association of externalizing problems with aggressive bullying behaviors has also been supported (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2017). Externalizing problems are strongly and closely related to deficits in executive functions associated with poor self-control, which are often linked to a negative bias in reading social interactions (Flores et al., 2020; Kuhn et al., 2017; Perry et al., 2018). These difficulties may be associated with the adoption of aggressive behaviors (Van Rest et al., 2020), as neutral behaviors are more likely to be interpreted as threatening. These results are also coherent with studies showing that difficulties in emotion and impulse regulation are strongly associated with engagement in aggressive behaviors (Van Rest et al., 2020). In addition to deficits in self-control, adolescents with externalizing problems may have difficulties interpreting and responding with accuracy to social interactions (Flores et al., 2020; Kuhn et al., 2017; Perry et al., 2018), which may lead to conflicts with peers that can escalate to violence. These difficulties managing social interactions possibly explain the increased engagement of adolescents with externalizing problems in bullying, both as aggressors and victims.

In what concerns the association of internalizing and externalizing problems with victimization behaviors, results support the assumption that more than specific vulnerabilities, bullies tend to exhibit more socioemotional adjustment problems. Adolescents showing socioemotional adjustment problems, which are associated with difficulties in reading social cues and managing conflicts, are more prone to engage in bullying, both as bullies and as victims (Busch et al., 2015; Horne & Socherman, 1996; Jenkins et al., 2014; Ledwell et al., 2013; Perren & Alsaker, 2006; Rupp et al., 2018; Sterzing et al., 2012).

Regarding the association of sex with the engagement in bullying aggressive and victimization behaviors, research shows that boys tend to more frequently engage in bullying aggressive behaviors (Jenkins et al., 2014; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015; Unnever & Cornell, 2003; Wang et al., 2012). However, contrary to what might be expected, as several studies show that girls are more often victims of bullying (Champion et al., 2003; Egan & Perry, 1998; Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012; Jenkins et al., 2014), boys were also more often victimized by bullies, although with a marginally significant result. A large body of research shows that boys are commonly victims and perpetrators of direct forms of bullying (Hong & Espelage, 2012). These results are possibly due to how boys interpret the various forms of bullying, as they probably perceive bullying behaviors as a normal part of the interaction with their peers, while girls possibly recognize in these behaviors the intention of harming another and an imbalance of power (Gordillo, 2012). Representations on masculinity, the influence of other male figures in adherence to or approval of bullying behaviors, as well as the influential role of their peers may also help explaining these gender differences (Steinfeldt et al., 2012).

Considering the association of the interaction between social skills and age with bullying aggressive behaviors, even though with a marginally significant result, the findings revealed that younger adolescents with more social skills tend to engage less frequently in bullying aggressive behaviors, while in older adolescents this is not observed. Younger adolescents possibly make an increased, conscious, and intentional use of social skills to accurately read and manage social complex situations, namely those which require dealing with conflicts with their peers and decode their implicit intentions, as they are less mature concerning cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. In fact, the acquisitions in abstract thought that occur during adolescence (Dumontheil, 2014) probably lead older adolescents to conquer an increased sense of confidence and perception of self-efficacy, which lead them to, almost in a unconscious and automatically manner, respond more adequately to social interactions.

Overall, these findings suggest that social skills and socioemotional adjustment problems (i.e., internalizing and externalizing difficulties) seem to explain bullying engagement, both as aggressor or as victim, in Portuguese adolescents. Therefore, it suggests that vulnerabilities, more than specific symptoms, should be considered as risk factors for bullying engagement. These results also highlight the importance of sex and age while explain the adolescents’ engagement in bullying behaviors.

This study adds to the existent literature the relevance of considering the role of mental health care during critical developmental stages, such as the adolescence period, with important clinical implications. Health professionals working in schools, teachers, parents, and community organizations supporting adolescents should be aware of the critical signs of internalizing and externalizing problems. Preventing psychopathology during adolescence, especially anxiety and depressive symptoms (internalizing problems) and aggressive and oppositional behavior (externalizing problems), may be an important approach to prevent bullying widespread. School and community programs may focus on promoting emotion regulation skills to mitigate bullying and its consequences, which seem to be closely linked to internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for determining causal links between the variables. Hence, future studies should consider assessments of social skills and bullying engagement behaviors at different moments to enable longitudinal comparisons. Although data collection took place during COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of this atypical period in the social relationships of the adolescents was not considered in the analyses, which may introduce a bias, as our results may not reflect the adolescents’ usual dynamics with their peers. The questionnaires were completed on-line, which did not allow to identify potential difficulties in understanding the items and to reflect on doubts concerning the responses to them. Therefore, it will be relevant to collect data in presence, to monitor the adolescents more closely, while completing the questionnaires. Nonetheless, teachers were asked to monitor the emotional impact of the SIBS on the adolescents, to identify potential signs of socio-emotional vulnerability, or even emotional disorganization. Although the teachers did not identify adverse or negative reactions the questionnaires completion, the research team committed to ensure psychological intervention for those adolescents who may feel vulnerable. The absence of information on participants’ psychiatric diagnoses is also a limitation of this study. Therefore, information on the presence of psychopathology should be gathered in future studies. Additionally, data were only collected in Porto district, which might bias the geographic representativeness of the sample. Further research should include adolescents from all the districts of Portugal to control for this bias. Furthermore, the perception of other informants, such as parents and teachers, regarding social skills and bullying should be considered to avoid social desirability and rater bias, as well as to obtain greater validity. Beyond these limitations, we did not collect information on parenting styles, socioeconomic status, teaching practices or classroom environment. Future studies should consider these variables to achieve a more comprehensive assessment of the factors underlying adolescents’ social dynamics and bullying behaviors.

Despite these limitations, this study offers an important contribution to clarifying the role of socioemotional problems in bullying engagement. Behavior problems appear to be strongly associated with engaging in aggressive and victimization behaviors. These findings suggest that interventions aiming to prevent and reduce internalizing and externalizing problems, as precursors of psychopathology, may help prevent and mitigate bullying and their negative effects on social interactions. Along with these interventions, promotion, preventive, and remediation school programs, focused on developing social skills, may also be important to reduce the impact of bullying and negative consequences and effects on physical and mental health among adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, we would like to thank all adolescents for engaging in this study. We also thank the collaboration of schools, teachers and families. We are grateful to Professor Ana Tomás de Almeida, for the kindness in sharing the Interpersonal Behaviour at School Scale (SIBS), and to Professor Maria Adelina Barbosa-Ducharne and Joana Soares for the availability in sharing the Social Skills Improvement System – Rating Scales (SSIS-RS). This work was conducted at the Centro de Investigação em Psicologia para o Desenvolvimento (CIPD) [The Psychology for Positive Development Research Center] (UID/PSI/04375), Lusíada University - North, Porto, supported by national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (UID/PSI/04375/2019).

References

Achenbach, T. (1966). The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: a factor analytic study. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–37.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T., Ivanova, M., Rescorla, L., & Turner, L. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems. Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications, 55(8), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012

Arslan, I., Lucassen, N., van Lier, P., Haan, A., & Prinzie, P. (2020). Early childhood internalizing problems, externalizing problems and their co-occurrence and (mal)adaptive functioning in emerging adulthood: a 16-year follow-up study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01959-w

Azevedo Da Silva, M., Gonzalez, J., Person, G., & Martins, S. (2019). Bidirectional Association between bullying perpetration and internalizing problems among youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth

Bashir, R., Fatima, G., & Ashraf, S. (2020). Prevalence and prevention strategies of violence in special schools: A quantitative survey. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 75-80. doi: 10.267/jbsee.v6i1.1030

Björkqvist, K. (2018). Gender differences in aggression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.030

Busch, V., Laninga-Wijnen, L., van Yperen, T., Schrijvers, A., & De Leeuw, J. (2015). Bidirectional longitudinal associations of perpetration and victimization of peer bullying with psychosocial problems in adolescents: A cross-lagged panel study. School Psychology International, 36(5), 532–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315604018

Card, N., Stucky, B., Sawalani, G., & Little, T. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79(5), 1185–1229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x

Cassiello-Robbins, C., & Barlow, D. (2016). Anger: The unrecognized emotion in emotional disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12139

Casper, D., & Card, N. (2016). Overt and relational victimization: A meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 88(2), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12621

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Violence prevention: Bullying research. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/youthviolence/bullyingresearch/index.html

Chaplin, T. M. (2015). Gender and emotion expression: A developmental contextual perspective. Emotion Review, 7(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914544408

Chaplin, T. M., & Aldao, A. (2013). Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 735–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030737

Cho, S., & Lee, J. (2018). Explaining physical, verbal, and social bullying among bullies, victims of bullying, and bully-victims: Assessing the integrated approach between social control and lifestyles-routine activities theories. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.018

Cosma, A., & Balazsi, R., & Baban, A. (2018). Bullying victimization and internalizing problems in school aged children: A longitudinal approach. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. An interdisciplinary journal, 22, 31-45. doi: 10.24193/cbb.2018.22.03

Darjan, I., Negru, M., & Ilie, D. (2020). Self-esteem – the decisive difference between bullying and assertiveness in adolescence? Journal of Educational Sciences, 1(41), 19-34. doi: 10.35923/JES.2020.102

Deniz, M., & Ersoy, E. (2016). Examining the relationship of social skills, problem solving and bullying in adolescents. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 8(1), 1-7. doi: 10.15345/iojes.2016.01.001

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Rodrigues, T. (2015). Being bullied and feeling ashamed: Implications for eating psychopathology and depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 44, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.005

Dumontheil, I. (2014). Development of abstract thinking during childhood and adolescence: The role of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 10, 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2014.07.009

Feijóo, S., O’Higgins-Norman, J., Foody, M., Pichel, R., Braña, T., Varela, J., & Rial, A. (2021). Sex differences in adolescent bullying behaviours. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2021a1

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.) SAGE.

Garaigordobil, M., & Machimbarrena, J. (2019). Victimization and perpetration of bullying/cyberbullying: Connections with emotional and behavioral problems and childhood stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 28, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a3

Garcia-Continente, X., Pérez-Giménez, A., Espelt, A., & Nebot Adell, M. (2013). Bullying among schoolchildren: Differences between victims and aggressors. Gaceta Sanitaria, 27(4), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.12.012

Gonzalez, E., Marques, S., Pinto, A., & Vaz, F. (2009). Exclusão social: Bullying na infância e na adolescência. Percursos, 4(14), 3–7.

Gordillo, I. C. (2012). Gender and role: variables that change the perception of bullying. Revista Mexicana de Psicologia, 29, 136–146.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system: Manual. American Guidance Service.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social skills improvement system: Rating scales manual. Pearson Education Inc..

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggressive Violent Behavior, 17, 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Jenkins, L., & Nickerson, A. (2019). Bystander Intervention in Bullying: Role of social skills and gender. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617735652

Holt, K., Vivolo-Kantor, M., Polanin, R., Holland, M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J. L., Wolfe, M., & Reid, G. (2015). Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics, 135(2), e496–e509. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1864

Horne, A., & Socherman, R. (1996). Profile of a bully: Who would do such a thing? Educational Horizons, 74(2), 77–83.

Hukkelberg, S., Keles, S., Ogden, T., et al. (2019). The relation between behavioral problems and social competence: A correlational meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2343-9

Huaqing Qi, C., & Kaiser, A. (2003). Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(4), 188–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214030230040201

Jenkins, L., Demaray, M., Fredrick, S., & Summers, K. (2014). Associations among middle school students’ bullying roles and social skills. Journal of School Violence, 15(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.986675

Jankauskiene, R., Kardelis, K., Sukys, S., & Kardeliene, L. (2008). Associations between school bullying and psychosocial factors. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 36(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.2.145

Jenkins, L., & Nickerson, A. (2017). Bystander intervention in bullying: Role of social skills and gender. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617735652

Keane, S., & Calkins, S. (2004). Predicting kindergarten peer social status from toddler and preschool problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jacp.0000030294.11443.41

Klomek, A., Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., Sarchiapone, M., et al. (2018). Bi-directional longitudinal associations between different types of bullying victimization, suicide ideation/attempts, and depression among a large sample of European adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(2), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12951

Košir, K., Klasinc, L., Špes, T., Pivec, T., Cankar, G., & Horvat, M. (2020). Predictors of self-reported and peer-reported victimization and bullying behavior in early adolescents: the role of school, classroom, and individual factors. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35, 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00430-y

Kramer, M., Krueger, R., & Hicks, B. (2007). The role of internalizing and externalizing liability factors in accounting for gender differences in the prevalence of common psychopathological syndromes. Psychological Medicine, 38(01). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291707001572

Ledwell, M., & King, V. (2013). Bullying and Internalizing Problems. Journal of Family Issues, 36(5), 543–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x13491410

Lee, K., Dale, J., Guy, A., & Wolke, D. (2018). Bullying and negative appearance feedback among adolescents: Is it objective or misperceived weight that matters? Journal of Adolescence, 63, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.008

Lemstra, M., Nielsen, G., Rogers, M., Thompson, A., & Moraros, J. (2012). Risk indicators and outcomes associated with bullying in youth aged 9-15 years. Canadian journal of Public Health = Revue canadienne de sante publique, 103(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404061

Marini, Z. A., Dane, A. V., Bosacki, S. L., & CURA, Y. (2006). Direct and indirect bully-victims: differential psychosocial risk factors associated with adolescents involved in bullying and victimization. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20155

Massing-Schaffer, M., Helms, S., Rudolph, K., Slavich, G., Hastings, P., Giletta, M., & Nock, & Prinstein, M. (2018). Preliminary Associations among Relational Victimization, Targeted Rejection, and Suicidality in Adolescents: A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 00(00), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1469093

Méndez, I., Ruiz-Esteban, C., & López-García, J. (2017). Risk and protective factors associated to peer school victimization. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00441

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

Mira, A., Verdasca, J., Barco, B., Castaño, E., & Carroza, T. (2017). Bullying escolar em escolas de ensino básico e de ensino secundário do Alentejo (Portugal). Revista Educação Temas e Problemas, 17, 55–78.

Morris, E., Zhang, B., & Bondy, S. (2006). Bullying and smoking: Examining the relationships in Ontario adolescents. The Journal of school health, 76(9), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00143.x

National Academies of Science, Engineeringe, and Medicine. (2016). Preventing bullying through science, policy and practice. The National Academic Press.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1999). Europe – Scandinava – Sweden. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano and P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of schoolbullying: a cross-national perspective (pp. 7-27). Routledge.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Perren, S., & Alsaker, F. (2006). Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610-2005.01445.x

Pontes, N., Ayres, C., Lewandowski, C., & Pontes, M. (2018). Trends in bullying victimization by gender among U.S. high school students. Research in Nursing & Health, 41(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21868

Price, M., Chin, M., Higa-McMillan, C., Kim, S., & Frueh, C. B. (2013). Prevalence and internalizing problems of ethnoracially diverse victims of traditional and cyber bullying. School Mental Health, 5(4), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-013-9104-6

Richard, J., Grande-Gosende, A., Fletcher, É., Temcheff, C., Ivoska, W., & Derevensky, J. (2019). Externalizing problems and mental health symptoms mediate the relationship between bullying victimization and addictive behaviors. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction, 18, 1081–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00112-2

Romera, E., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Rodriguez-Barbero, S., & Falla, D. (2019). How do you think the victims of bullying feel? A study of moral emotions in primary school. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01753

Rosenfield, S. (2000). Gender and dimensions of the self: Implications for internalizing and externalizing behavior. In E. Frank (Ed.), American Psychopathological Association series. Gender and its effects on psychopathology (pp. 23–36). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Rupp, S., Elliott, S., & Gresham, F. (2018). Assessing elementar students’ bullying and related social behaviors: Cross-informant consistency across school and home environments. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.028

Sentse, M., Prinzie, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2016). Testing the direction of longitudinal paths between victimization, peer rejection, and different types of internalizing problems in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(5), 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0216-y

Skarstein, S., Helseth, S., & Kvarme, L. G. (2020). It hurts inside: a qualitative study investigating social exclusion and bullying among adolescents reporting frequent pain and high use of non-prescription analgesics. BMC Psychology, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00478-2

Smith, P., López, L., & Görzig, A. (2019). Consistency of gender differences in bullying in cross-cultural surveys. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.04.006

Steinfeldt, J. A., Vaughan, E. L., Lafollette, J. R., & Steinfeldt, M. C. (2012). Bullying among adolescent football players: Role of masculinity and moral atmosphere. Psychology of Men and Masculinities, 13, 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026645

Sterzing, P., Shattuck, P., Narendorf, S., Wagner, M., & Cooper, B. (2012). Bullying involvement and autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates of bullying involvement among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(11), 1058–1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.790

Stubbs-Richardson, M., Sinclair, H. C., Goldberg, R. M., et al. (2018). Reaching out versus lashing out: Examining gender differences in experiences with and responses to bullying in high school. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-017-9408-4

Swearer, M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038929

Tan, K., Oe, J., & Minh, L. (2018). How does gender relate to social skills? Exploring differences in social skills mindsets, academics, and behaviors among high-school freshmen students. Psychology in the Schools, 55(4), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22118

Tsitsika A.K., Barlou E., Andrie E., Dimitropoulou C., Tzavela E.C., Janikian M. (2014) Bullying behaviors in children and adolescents: “An ongoing story”. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 1-4. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00007

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019a). School violence and bullying a major global issue. Retrieved from en.unesco.org

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019b). Behind the numbers: Ending school violence and bullying. Retrieved from en.unesco.org

Volk, A., Dane, A., & Marini, A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redifinition. Developmental Review, 34(4), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001

Williams, S., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Wornell, C., & Finnegan, H. (2017). Adolescents transitioning to high school: Sex differences in bullying victimization associated with depressive symptoms, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts. The Journal of School Nursing, 33(6), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840516686840

Zsila, Á., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M., & Demetrovics, Z. (2019). Gender differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and perpetration: The role of anger rumination and traditional bullying experiences. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction, 17, 1252–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9893-9

Zych, I., Farrington, D., Llorent, V., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020a). Childhood Risk and Protective Factors as Predictors of Adolescent Bullying Roles. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 3(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00068-1

Zych, I., Ttofi, M., Llorent, V., Farrington, D., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020b). A longitudinal study on stability and transitions among bullying roles. Child Development, 91(2), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13195

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Sousa, M.L., Peixoto, M.M. & Cruz, S. The association of social skills and behaviour problems with bullying engagement in Portuguese adolescents: From aggression to victimization behaviors. Curr Psychol 42, 11936–11949 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02491-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02491-z