Abstract

The present study examines and explores the indirect effects of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity on well-being, namely self-esteem and life satisfaction, through presence of and search for meaning in life, and its gender difference among adolescents. 301 girls and 395 boys from Hong Kong participated in this cross-sectional survey study. Independent t-test, correlation and four mediation model analyses with a bootstrap of 5000 samples were conducted. Girls score higher in extrinsic religiosity (personal) and search for meaning in life; lower in self-esteem compared with boys. Presence of meaning in life was found to positively mediate the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic personal religiosity on self-esteem and life satisfaction for boys but is not significant for girls. However, intrinsic religiosity promotes higher search for meaning in life, which in turn lowers self-esteem only for girls. The indirect effect of extrinsic social religiosity on well-being was not significant for both genders. Finding suggests that boys benefit more from religiosity on well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Individuals who have a strong identity have “the ability to experience their sense of who they are, and also act on that sense, in a way that has continuity and sameness” (Levesque, 2011, p. 813). In particular, adolescents are experiencing the psychosocial stage of “identity vs. role confusion” (Erikson, 1968). At this stage, adolescents explore and challenge their religious beliefs, experience and search for meaning in life from religious experience with increased abstract thinking ability (Kim & Esquivel, 2011). By internalizing their religious belief, adolescents build a stronger identity (Kim & Esquivel, 2011; Steger et al., 2011). One with a solid identity has higher self-esteem and life satisfaction compared with one who is uncertain about his or her identity (Kahn et al., 2014; Luyckx et al., 2013).

According to terror management theory, the inevitable death and innate desire for life brings anxiety and potentially terror (Pyszczynski et al., 2004). Thus, humans are driven to build or search for a positive worldview, or meaning in life, including what is important for one’s life, and search for literal and symbolic immortality. Literal immortality refers to the religious promise of after-life and heaven to those who are faithful and practice the standard set by their religion. Symbolic immortality refers to when people feels that they belong and contribute to something bigger which will continue after their life. This theory further extends that self-esteem and well-being will be promoted when one believes that he or she is fulfilling what is important for one’s life and the validity of his or she worldview. Literal immortality will be focused in this study.

Presence of meaning in life (MIL-P) refers to the extent to which people believe their lives are important and meaningful, and those with higher MIL-P find their lives more purposeful and understandable (Steger et al., 2006; Steger & Frazier, 2005). Search for meaning in life (MIL-S) refers to the activity and degree of effortful exploration toward understanding and building MIL, purposes, and importance of life (Steger et al., 2006; Steger et al., 2008). People with intrinsic religiosity want to have a spiritual development in religion and live out their faith through actions. People with extrinsic religiosity seek religion for other means. People with extrinsic personal religiosity (extrinsic-personal) seek religion for comfort, peace, relief in face of difficulties, whereas people with extrinsic social religiosity (extrinsic-social) go to church to make friends or hang out with friends (Maltby, 2002).

Mediating Role of Meaning in Life on the Effect of Religiosity on Well-Being

Intrinsic Religiosity

Presence of MIL has consistently been found to positively mediate the effect of intrinsic religiosity, religiousness, religious commitment and spirituality on well-being including self-esteem and satisfaction with life among adolescents and young adults (Kaiser-Ahmad & Iqbal, 2017; Kashdan & Nezlek, 2012; Steger & Frazier, 2005; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014; You & Lim, 2019). However, there is an inconsistent result. Sillick and Cathcart (2014) found that intrinsic religiosity decreases MIL-P which in turn, decreases happiness for female young adults only. There has not been a consensus as to the reasons for this relationship. Hence, it is worth investigating the mediating effect of MIL-P to see if our result replicates the vast majority of the previous results, and exploring its potential gender differences.

On the other hand, MIL-S fails to mediate the relationship between religious commitment and mental well-being among 92 adolescents and young adults; but religious commitment increases MIL-S significantly (Kaiser-Ahmad & Iqbal, 2017). This is the only study found to examine MIL-S as a mediator between these variables. However, religious commitment refers to the level of spiritual and behavioural adherence of religion (Worthington Jr et al., 2003), which differs from intrinsic religiosity of an innate desire to grow spiritually. Furthermore, this result drawn from relatively low sample size can create a false positive result (Hackshaw, 2008). Furthermore, there has been inconsistent results on whether intrinsic religiosity promotes MIL-S. Intrinsic religiosity has been found to increase (Kaiser-Ahmad & Iqbal, 2017), decrease for people with higher level of empathy (Routledge et al., 2017), and not associated with (Horning et al., 2011; Park & Yoo, 2016) MIL-S among adolescents, young adults and older adults. There is also inconsistent evidence on the relationship between MIL-S and psychological well-being. MIL-S predicts higher positive emotions (Pezirkianidis et al., 2016), but is associated with lower self-esteem among adolescents (Kiang & Fuligni, 2010), and did not predict or associate with psychological well-being (Demirbaş-Çelik & Keklik, 2019; Krok, 2015b). It was proposed that whether search for meaning brings positive or negative outcomes depends on the type of search (Steger et al., 2008). In an adaptive search, people search for meaning based on insights and ambitions gained from life challenges and desires to seek a positive experience, which leads to positive outcomes. In a maladaptive search, people search for meaning to avoid challenging or negative experiences, which leads to negative outcomes. Because of the limitation in previous study and conflicting findings for the relationship between MIL-S and intrinsic religiosity along with well-being, it is important to explore MIL-S as a mediator between intrinsic religiosity and well-being.

Extrinsic Religiosity

As for extrinsic religiosity, there has been opposite mediating results across genders. For female, extrinsic religiosity decreases MIL-P, which in turn, decreases subjective well-being (You & Lim, 2019). For male, extrinsic religiosity increases MIL-P, which in turn, increases happiness (Sillick & Cathcart, 2014). Extrinsic religiosity has been found to decrease MIL-P for people with low level of self-concept clarity (Błażek & Besta, 2012) and not associated with MIL-P (Francis et al., 2010; Krok, 2015a). However, only MIL-P has been examined for its mediating role and its relationship with extrinsic religiosity, but not for MIL-S.

Extrinsic religiosity (personal and social) predict and associate with higher well-being: both factors and higher religious satisfaction (Steffen et al., 2015); extrinsic-personal and higher self-esteem, mindfulness and self-control (Ghorbani et al., 2017); extrinsic-social and lower trait anxiety, depressive symptoms (Steffen, 2014), less guilt (Ghorbani et al., 2017) and more happiness (Sillick & Cathcart, 2014). However, these factors also account for lower well-being: both factors and lower self-esteem for men (Maltby & Day, 2000); extrinsic-personal and more guilt (Ghorbani et al., 2017); extrinsic-social and higher depressive symptoms (Maltby & Day, 2000). Extrinsic religiosity has also been found to not predict or associate with well-being: both factors and positive, negative affect (Steffen et al., 2015), life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, well-being (Ardelt, 2003) and self-esteem for female (Maltby & Day, 2000); extrinsic-personal and happiness (Sillick & Cathcart, 2014) and depression for female (Maltby & Day, 2000). Given the inconsistent results from extrinsic religiosity and extrinsic (personal versus social) on well-being, it is important to explore the different effects of these two types of extrinsic religiosity on well-being through meaning in life and the gender differences.

Current Study

The present study examines and explores the mediating role of meaning in life in the relationship between religiosity and well-being, and its gender differences; to hopefully bring more understanding of the inconsistent associations between examined variables and if gender differences exist as previous studies suggested.

The present study hypothesizes:

-

(1): MIL-P mediates the effect of intrinsic religiosity on self-esteem and satisfaction with life.

The present study explores:

-

(1): MIL-S as a mediator on the effect of intrinsic religiosity on self-esteem and satisfaction with life.

-

(2): MIL-P and MIL-S as a mediator on the effect of extrinsic religiosity (personal and social) on self-esteem and satisfaction with life.

-

(3): There has been conflicting evidence on gender differences in these mediating relationships and no theoretical framework has been found to explain them. Thus, we will explore the gender difference all of the relationships examined.

Methodology

Participants and Procedure

To examine the influence of religiosity on adolescents’ self-esteem and satisfaction with life, and the roles of MIL-P and MIL-S on such a relationship between genders, a quantitative survey study was conducted. Participants studying in secondary and post-secondary schools from Hong Kong were recruited to participate in this study. In order to further help the participants understand the question items, the survey items were translated into Chinese by the backward translation technique with further triangulation by a panel of bilingual experts in China and in Canada. It aims to secure equivalent meanings across the original English version and the translated Chinese version. Informed consent was obtained, and for participants who were under 18 of age, parental consents were also collected beforehand. Once the participants have also agreed to participate voluntarily, survey was distributed and collected. All data were collected using paper-and-pen method.

Measures

Religiosity

Adolescents’ level of intrinsic, extrinsic-personal, and extrinsic-social religious orientations were assessed by the Age universal intrinsic-extrinsic scale (AUIE) (Maltby, 1999). It uses simpler language to indicate one’s religiosity where reliable and valid results were generated from both adult and schoolchild samples. The items are scored on a three-point scale (3 = Yes, 2 = Not Certain, and 1 = No). The AUIE was able to obtain satisfactory reliability and validity from previous studies, within the United States, the United Kingdom, Irish, and Hong Kong participants (Liu, 2013; Maltby, 1999, Maltby, 2002). It also proves to be a measurement applicable to both religious and non-religious individuals (Maltby, 1999; Maltby & Lewis, 1996). Consistent with previous literature, satisfactory reliability coefficients were obtained on all three of the subscales in this study for both male (for intrinsic, α = .87; for extrinsic-personal, α = .81; for extrinsic-social, α = .73) and female (for intrinsic, α = .90; for extrinsic-personal, α = .81; for extrinsic-social, α = .71) participants. In this study, a polytheistic perspective of religions was considered, where participants who identified themselves as religious can believe in more than one God.

Meaning in Life

In this study, MIL is measured by the meaning in life questionnaire (MILQ), developed by Steger et al. (2006). It is defined by the goal directedness or purposefulness of an individual. It is a 10-item questionnaire with a seven-point Likert scale. It is divided by two subscales, namely MIL-P and MIL-S (Steger et al., 2006). This scale has been widely used in studies about one’s well-being and religiousness (Schlegel, Hicks, Arndt, & King, 2009; Dunn & O'Brien, 2009; Steger & Frazier, 2005; Triplett, Tedeschi, Cann, Calhoun, & Reeve, 2012). Both the male (for MIL-P, α = .74; for MIL-S, α = .85) and female (for MIL-P, α = .81; for MIL-S, α = .84) samples have shown consistent reliable results in this study.

Self-Esteem

The ten-item Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (RSES) was used to examine the participants’ global self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965; Schmitt & Allik, 2005). It has been used in more than 53 countries, including adolescents in Hong Kong (Kashdan & Yuen, 2007; Shek, 1998) and has obtained a high level of reliability and validity (Schmitt & Allik, 2005). The Cronbach’s α of the self-esteem construct for both the male and female samples in this study were also satisfactory, with α = .80 and α = .83 respectively.

Satisfaction with Life

The Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) by Diener et al. (1985) has five items under a seven-point Likert scale. It is used to assess one’s judgment of his/her quality of life. SWLS has been validated and used for research related to the well-being of adolescents in Hong Kong (Sachs, 2003; Sun & Shek, 2010). For this study, the reliability for male and female samples are α = 0.86 and α = 0.84 respectively.

Demographic Characteristics

In addition to the psychometric scales, participants were also asked about their demographic characteristics, such as their gender (male and female), religious status (religious and non-religious), and age. The responses were self-reported and self-identified.

Statistical Analyses

To begin, a table was used to demonstrate the basic demographic characteristics of both gender samples. It was then followed by independent T-tests to observe the gender differences among the four constructs. After that, a split file correlation analysis with Pearson’s r was employed to assess the inter-correlations of the constructs for both samples respectively. Lastly, four mediation model analyses with a bootstrap of 5000 samples were adopted to investigate the mediating effects of both MIL-P and MIL-S on the relationships between religiosity and self-esteem as well as satisfaction with life, while simultaneously controlled the effects the participants’ religious statuses. The bootstrap confidence interval method is also regarded to achieve the highest statistical power across different methods for mediation models (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Schoemann et al., 2017; Zhang, 2014). The mediation analyses were conducted with PROCESS developed by Hayes (2012). This technique was supported by various studies that explore the relationships between religion-related constructs (Abu-raiya, Pargament, & Krause, 2016; Jankowski & Sandage, 2014; McElroy-Heltzel et al, 2018; Sharma & Singh, 2019; Van Tongeren, Hook, & Davis, 2013), and positive psychology constructs (Abu-raiya et al., 2016; Sharma & Singh, 2019; Van Tongeren, Green, Davis, Hook, & Hulsey, 2016).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In the process of data collection in a few secondary schools, 828 students successfully completed the survey. 42.03% of the sample identify themselves as female (n = 348), with the remaining 57.97% identifying themselves as male (n = 480). The demographic characteristics of the participants were shown on Table 1. Both female and male samples have similar distribution in terms of religious status and age.

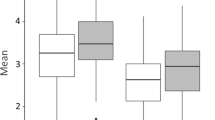

Gender Differences on Religiosity, Meaning in Life, Self-Esteem, and Satisfaction with Life

Table 2 shows the differences between both the male and female participants in terms of their religiosity, MIL-P and MIL-S, as well as self-esteem and satisfaction with life. Female participants had significantly higher levels of intrinsic religiosity (for female participants, M = 2.00, SD = 0.62. For male participants, M = 1.90, SD = 0.56, t = 2.28, p < .05), extrinsic personal religiosity (for female participants, M = 2.19, SD = 0.67. For male participants, M = 2.03, SD = 0.63, t = 3.35, p < .01), MIL-S (for female participants, M = 5.38, SD = 0.97. For male participants, M = 5.16, SD = 1.15, t = 2.80, p < .01), and a lower self-esteem (for female participants, M = 2.61, SD = 0.47. For male participants, M = 2.69, SD = 0.48, t = −2.07, p < .05), than of male participants.

Correlations among Variables for both Samples

Table 3 illustrates the correlations among the variables, split by male and female samples on each diagonal. Both samples share a few similar results, such as positive correlations between different types of religiosity and MIL, as well as positive correlations between Self-esteem and Satisfaction with life. However, for male participants, the three subscales of religiosity are significantly and positively correlated to Satisfaction with life, while it is not significant for female participants.

Mediation Model Analyses

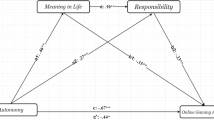

Regarding the use of self-esteem as a dependent variable, after controlling one’s religious status, for male participants, the results of the analyses reveal a significantly fit mediation models, F(4, 415) = 19.64, p < .001, R2 = .16. The overall statistical model is depicted on Fig. 1. All of Intrinsic religiosity, Extrinsic-personal religiosity, and Extrinsic-social religiosity do not show a significant total effect (β = −0.03, SE = 0.05, ns, 95% CI: −0.12, 0.07 for Intrinsic religiosity; β = 0.05, SE = 0.04, ns, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.13 for Extrinsic-personal religiosity; and β = −0.05, SE = 0.04, ns, 95% CI: −0.14, 0.03 for Extrinsic-social religiosity). At the same time, MIL-P demonstrates a significant positive prediction on one’s Self-esteem, with β = 0.17, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.22. The positive indirect effects of MIL-P in mediating the relationships between Intrinsic religiosity and self-esteem, as well as that between Extrinsic-Personal religiosity and self-esteem are significant, which are β = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.10; and β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.08 respectively.

For the same sample on satisfaction with life as the outcome variable, the results of the analyses also show significantly fit mediation models, F(4, 403) = 24.29, p < .001, R2 = 0.19, which is also portrayed on Fig. 2. In this case, all three types of religiosity have significant positive total effects towards one’s Satisfaction with life (β = 0.54, SE = 0.13, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.79 for Intrinsic religiosity; β = 0.59, SE = 0.11, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.37, 0.80 for Extrinsic-personal religiosity; and β = 0.35, SE = 0.12, p < .01, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.59 for Extrinsic-social religiosity). After inputting the two mediators, the direct effects of the three types of religiosity are weakened but still significant (β = 0.40, SE = 0.12, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.64 for Intrinsic religiosity; β = 0.48, SE = 0.10, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.69 for Extrinsic-personal religiosity; and β = 0.31, SE = 0.11, p < .01, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.52 for Extrinsic-social religiosity). Similar to the previous model, MIL-P has been a significantly positive indirect effect on the relationships between Intrinsic religiosity (β = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.25) and Satisfaction with life, as well as that between Extrinsic-Personal religiosity and Satisfaction with life (β = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p < .05, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.21).

As for female participants, the mediation model is also significantly fit with Self-esteem as the dependent variable, F(4, 316) = 40.15, p < .001, R2 = 0.34. From Fig. 3, it is marked that MIL-P has a positive prediction on participants’ Self-esteem, β = 0.26, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.30, while the total effect of Intrinsic religiosity is not significant, β = −0.08, SE = 0.05, ns, 95% CI: −0.19, 0.03, it has a significant negative direct effect, β = −0.12, SE = 0.04, p < .01, 95% CI: −0.17, −0.02. Extrinsic-personal religiosity does not have a significant total effect on Self-esteem, β = −0.04, SE = 0.04, ns, 95% CI: −0.11, 0.03; whereas there is a significantly negative total effect for Extrinsic-social religiosity, β = −0.12, SE = 0.05, p < .05, 95% CI: −0.21, −0.03. Unlike the male participants, the female participants’ MIL-S has a significant negative prediction on their Self-esteem, β = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p < .05, 95% CI: −0.10, −0.01. MIL-S served as a statistically significant negative mediator in this model for Intrinsic religiosity and Self-esteem, β = −0.01, SE = 0.01, p < .05, 95% CI: −0.04, −0.00.

Finally, the mediation model with one’s Satisfaction with life as the outcome variable for female participants is significantly fit, F(4, 313) = 22.19, p < .001, R2 = 0.22. The details of the model were also demonstrated in Fig. 4. All three types of religiosity do not have a significant total effect on their Satisfaction with life, β = 0.15, SE = 0.14, ns, 95% CI: −0.12, 0.42 for Intrinsic religiosity; β = 0.05, SE = 0.11, ns, 95% CI: −0.17, 0.26 for Extrinsic-personal religiosity; and β = 0.04, SE = 0.12, ns, 95% CI: −0.20, 0.28 for Extrinsic-social religiosity. MIL-P remained to be positively predicting participants’ Satisfaction with life, β = 0.52, SE = 0.06, p < .001, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.63. None of the indirect effects was statistically significant in this model.

Discussion

The present study’s hypothesis is supported for male only. For male, MIL-P mediates the positive effect of intrinsic religiosity on self-esteem and life satisfaction. Regarding the exploration on MIL-S as a mediator, effect of extrinsic religiosity as a predictor and gender differences in all mediating relationships, this study highlights the interesting result on gender differences. For male, MIL-S does not mediate religiosity variables and self-esteem along with life satisfaction. However, MIL-P mediates the relationship between extrinsic-personal on these two variables. Extrinsic religiosity is not a significant predictor in all proposed mediating relationship for female. For female, intrinsic religiosity promotes MIL-S, which in turn, decreases self-esteem. Life satisfaction is not a significant dependent variable for girls in all proposed mediating relationship. MIL-P does not mediate the effect of all religiosity variables on self-esteem and life satisfaction for female. Lastly, extrinsic-social is not a significant predictor across all mediating relationship regardless of gender.

The present study is novel in providing a comprehensive framework on the mediating relationship of presence of, and search for MIL between all religiosity variables on self-esteem and life satisfaction; and to compare these relationships across gender. Intrinsic religiosity and its related constructs have consistently found to have an indirect effect on well-being through MIL-P (Kaiser-Ahmad & Iqbal, 2017; Kashdan & Nezlek, 2012; Steger & Frazier, 2005; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014; You & Lim, 2019). The present study only finds this true for boys. Current finding contradicts with Sillick and Cathcart’s (2014) result on negative mediating effect of MIL-P between intrinsic religiosity and well-being for girls, where this study finds no mediating relationship between these variables for female. MIL-P has only been examined for its mediating role on the effect of extrinsic religiosity as one variable on well-being without separating between extrinsic-personal and extrinsic-social (Sillick & Cathcart, 2014; You & Lim, 2019). It is important to separate these two variables because only extrinsic-personal has a positive relationship with intrinsic religiosity. People can have an innate desire to grow religiously and receive personal comfort from God(s) at the same time. Supporting our results, Extrinsic-personal is associated with intrinsic religiosity, less religious doubt, private religiousness and number of religious activity (Pargament et al., 2011; Williamson et al., 2010). This may explain why intrinsic religiosity and extrinsic-personal are both significant predictors in the mediating relationship of MIL-P on self-esteem and life satisfaction for boys. The remaining results will be discussed focusing on gender differences and extrinsic-social.

Female is often found to be more religious, attend religious services more and feel closer to God(s) compared with male (Kim & Kim, 2017). It is surprising that our result finds that boys solely benefit from intrinsic religiosity on self-esteem and life satisfaction and girls do not receive positive impact from religiosity in this study, but several research results correspond to this. A systematic review of 20 studies found that religiosity/spirituality variables associated with mental well-being variables stronger for male than for female (Wong et al., 2006). Extrinsic-personal offset the effect of stress on alcohol consumption for male only (Krause et al., 2018). Intrinsic religiosity and religious attendance are associated with lower trait anxiety and lower suicidal ideation for boys only whereas non-significant results are found for girls (Bearman & Moody, 2004; Davis et al., 2003). Three reasons may account for this result. One is that in face of trouble, boys tend to believe God(s) will help them whereas girls tend to believe that they are punished because of their sins (Yildiz, 2018). Another possible reason is that female experience more ambiguity and worries on religion compared with male (Yildiz, 2018). Female who are uncertain about their religion is associated with higher depression, but those who are certain is associated with lower depression. This result does not appear among male (Eliassen et al., 2005). The other reason is that Marcia (1993) proposes boys and girls develop their identity differently. Boys tend to actualize their goals through ideological spectrums including religion, whereas girls aim toward developing interpersonal relationship. Female also receives higher degree of social support from more sources compared with male, including friends, family and colleagues (van Daalen et al., 2005).

Extrinsic-social fails to serve as a predictor for all mediating relationships. Extrinsic-social solely focuses on using religion for other ends, which is building social networks at church (Maltby, 2002). In the present study, both of the MIL variables do not mediate the relationship between extrinsic-social and well-being for both genders. The relationship between extrinsic-social and well-being may need to take account of perceived social support and interpersonal skills. Significant prediction of extrinsic-social on emotional well-being is no longer significant after controlling the degree of perceived social support (Doane et al., 2014). Extrinsic-social is also associated with higher social dysfunction (Maltby & Day, 2003). Doane et al. (2014) argued that individual who use religion as a mean to gain social support may be due to the fact that they perceive themselves as having lower social support and interpersonal skills. Therefore, perceived social support and interpersonal skills may explain the relationship between extrinsic-social and well-being better than meaning in life.

Limitation and Further Studies

The present study employs a cross-sectional design so it is difficult to be clear about the sequence of the constructs: does religiosity promotes subsequent meaning in life for boys and motivates search for meaning in life for girls? Does meaning in life then affect well-being and is the effect of MIL long lasting? In past literature, MIL-P is associated with life satisfaction a year later but MIL-S does not associate with life satisfaction later (Steger & Kashdan, 2007). Further longitudinal study can help to clarity more about the sequence of these variables.

Moreover, it is uncertain of how intrinsic religiosity and extrinsic-personal interact with each other on MIL and well-being for boys. It is worth investigating which of these variables has a stronger impact and their interaction given their positive effects in this study.

Present result suggests that faith-based meaning-making intervention can especially be advantageous in promoting self-esteem and life satisfaction for male adolescents. Meaning-making intervention and psychotherapy were found to significantly improve self-esteem among Chinese university students and patients with cancer (Cheng et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2006).

The present study is novel to provide a well-rounded mediating structure of MIL-P and MIL-S on the effect of intrinsic religiosity, extrinsic-personal and extrinsic-social on self-esteem and life satisfaction. Boys benefit from intrinsic religiosity and extrinsic-personal through enhancing MIL-P; when girls suffer through intrinsic religiosity through promoting MIL-S. Longitudinal study can be conducted in the future to examine the sequence of these variables. The present study encourages research on the interaction between intrinsic religiosity and extrinsic-personal on well-being. Lastly, faith-based meaning-making intervention is promising in promoting self-esteem and life satisfaction especially for boys.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the majority of participants are minor.

References

Abu-Raiya, H., Pargament, K. I., & Krause, N. (2016). Religion as problem, religion as solution: Religious buffers of the links between religious/spiritual struggles and well-being/mental health. Quality of Life Research, 25(5), 1265–1274.

Ardelt, M. (2003). Effects of religion and purpose in life on Elders' subjective well-being and attitudes toward death. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 14(4), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J078v14n04_04.

Bearman, P. S., & Moody, J. (2004). Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.1.89.

Błażek, M., & Besta, T. (2012). Self-concept clarity and religious orientations: Prediction of purpose in life and self-esteem. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 947–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9407-y.

Cheng, M., Hasche, L., Huang, H., & Su, X. S. (2015). The effectiveness of a meaning-centered psychoeducational group intervention for Chinese college students. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(5), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.5.741.

Davis, T. L., Kerr, B. A., & Kurpius, S. E. R. (2003). Meaning, purpose, and religiosity in at-risk youth: The relationship between anxiety and spirituality. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 31(4), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710303100406.

Demirbaş-Çelik, N., & Keklik, İ. (2019). Personality factors and meaning in life: The mediating role of competence, relatedness and autonomy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 995–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9984-0.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Doane, M. J., Elliott, M., & Dyrenforth, P. S. (2014). Extrinsic religious orientation and well-being: Is their negative association real or spurious? Review of Religious Research, 56(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0137-y.

Dunn, M. G., & O'Brien, K. M. (2009). Psychological health and meaning in life: Stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(2), 204–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986309334799.

Eliassen, A. H., Taylor, J., & Lloyd Donald, A. (2005). Subjective religiosity and depression in the transition to adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44(2), 187–199.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton & Co..

Francis, L. J., Jewell, A., & Robbins, M. (2010). The relationship between religious orientation, personality, and purpose in life among an older Methodist sample. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 13(7–8), 777–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670802360907.

Ghorbani, N., Watson, P. J., Tahbaz, S., & Chen, Z. J. (2017). Religious and psychological implications of positive and negative religious coping in Iran. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(2), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0228-5.

Hackshaw, A. (2008). Small studies: Strengths and limitations. European Respiratory Journal, 32(5), 1141–1143. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00136408.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Horning, S. M., Davis, H. P., Stirrat, M., & Comwell, R. E. (2011). Atheistic, agnostic, and religious older adults on well-being and coping behaviors. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(2), 177–188.

Jankowski, P. J., & Sandage, S. J. (2014). Attachment to God and humility: Indirect effect and conditional effects models. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42(1), 70–82.

Kahn, S., Zimmerman, G., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Getzels, J. W. (2014). Relations between identity in young adulthood and intimacy at midlife. In M. Csikszentmihalyi (Ed.), Applications of flow in human development and education: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pp. 327–338). Springer Netherlands.

Kaiser-Ahmad, D., & Iqbal, N. (2017). Religious commitment and well-being in college students: Examining conditional indirect effects of meaning in life. Journal of Religion and Health, 58, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0538-2.

Kashdan, T. B., & Yuen, M. (2007). Whether highly curious students thrive academically depends on perceptions about the school learning environment: A study of Hong Kong adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 31(4), 260–270.

Kashdan, T. B., & Nezlek, J. B. (2012). Whether, when, and how is spirituality related to well-being? Moving beyond single occasion questionnaires to understanding daily process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(11), 1523–1535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212454549.

Kiang, L., & Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(11), 1253–1264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z.

Kim, S., & Esquivel, G. B. (2011). Adolescent spirituality and resilience: Theory, research, and educational practices. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7), 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20582.

Kim, S., & Kim, C. Y. (2017). Korean American adolescents’ depression and religiousness/spirituality: Are there gender differences?: Research and Reviews. Current Psychology, 36(4), 823–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9471-x.

Krause, N., Pargament, K. I., Hill, P. C., & Ironson, G. (2018). Assessing gender differences in the relationship between religious coping responses and alcohol consumption. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 21(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1455652.

Krok, D. (2015a). Religiousness, spirituality, and coping with stress among late adolescents: A meaning-making perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.004.

Krok, D. (2015b). The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2292–2308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9983-3.

Lee, V., Cohen, S. R., Edgar, L., Laizner, A. M., & Gagnon, A. J. (2006). Meaning-making intervention during breast or colorectal Cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3133–3145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.041.

Levesque, R. J. R. (2011). Ego identity. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 813–814). Springer New York.

Liu, J. K. K. (2013). Idol worship, religiosity, and self-esteem among university and secondary students in Hong Kong (Outstanding Academic Papers by Students (OAPS)). Retrieved from City University of Hong Kong, CityU Institutional Repository.

Luyckx, K., Klimstra, T. A., Duriez, B., Petegem, S. V., Beyers, W., Teppers, E., & Goossens, L. (2013). Personal identity processes and self-esteem: Temporal sequences in high school and college students. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.10.005.

Maltby, J. (1999). The internal structure of a derived, revised, and amended measure of the Religious Orientation Scale: The ‘Age-Universal’IE scale–12. Social Behavior and Personality, 27(4), 407–412.

Maltby, J. (2002). The age universal I-E Scale-12 and orientation toward religion: Confirmatory factor analysis. The Journal of Psychology, 136(5), 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980209605550.

Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2000). Depressive symptoms and religious orientation: Examining the relationship between religiosity and depression within the context of other correlates of depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 383–393.

Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2003). Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: Assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(7), 1209–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00110-1.

Maltby, J., & Lewis, C. A. (1996). Measuring intrinsic and extrinsic orientation toward religion: Amendments for its use among religious and non-religious samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(6), 937–946.

Marcia, J. (1993). The status of statuses: Research review. In J. Marcia, A. Waterman, D. Matteson, S. Archer, & J. Orlofsky (Eds.), Ego identity: A handbook for psychological research (pp. 22–41). Springer-Verlag.

McElroy-Heltzel, S. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., Gazaway, S., Ordaz, A., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., ... Stargell, N. A. (2018). The role of spiritual fortitude and positive religious coping in meaning in life and spiritual well-being following hurricane Matthew. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 37(1), 17–27.

Pargament, K., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a Short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2010051.

Park, C. J., & Yoo, S.-K. (2016). Meaning in life and its relationships with intrinsic religiosity, deliberate rumination, and emotional regulation. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12151.

Pezirkianidis, C., Stalikas, A., Efstathiou, E., & Karakasidou, E. (2016). The relationship between meaning in life, emotions and psychological illness: The moderating role of the effects of the economic crisis. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 4(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejcop.v4i1.75.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). Spss and sas procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent child. Princeton University Press.

Routledge, C., Roylance, C., & Abeyta, A. A. (2017). Further exploring the link between religion and existential health: The effects of religiosity and trait differences in Mentalizing on indicators of meaning in life. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(2), 604–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0274-z.

Sachs, J. (2003). Validation of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Hong Kong university students. Psychologia, 46(4), 225–234.

Schlegel, R. J., Hicks, J. A., Arndt, J., & King, L. A. (2009). Thine own self: true self-concept accessibility and meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(2), 473–490.

Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and cultures pecific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 623–642.

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386.

Sharma, S., & Singh, K. (2019). Religion and well-being: the mediating role of positive virtues. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(1), 119–131.

Shek, D. T. (1998). A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents' and parents' perceptions of family functioning and well-being. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159(4), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221329809596160.

Sillick, W. J., & Cathcart, S. (2014). The relationship between religious orientation and happiness: The mediating role of purpose in life. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 17(5), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2013.852165.

Steffen, P. R. (2014). Perfectionism and life aspirations in intrinsically and extrinsically religious individuals. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 945–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9692-3.

Steffen, P. R., Clayton, S., & Swinyard, W. (2015). Religious orientation and life Aspirationsre. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(2), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9825-3.

Steger, M. F., Bundick, M. J., & Yeager, D. (2011). Meaning in life. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1666–1677). Springer New York.

Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 574–582.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93.

Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. (2007). Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8.

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x.

Sun, R. C., & Shek, D. T. (2010). Life satisfaction, positive youth development, and problem behaviour among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 95(3), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9531-9.

Triplett, K. N., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., & Reeve, C. L. (2012). Posttraumatic growth, meaning in life, and life satisfaction in response to trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(4), 400–410.

van Daalen, G., Sanders, K., & Willemsen, T. M. (2005). Sources of social support as predictors of health, psychological well-being and life satisfaction among dutch male and female dual-earners. Women & Health, 41(2), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v41n02_04.

Van Tongeren, D. R., Hook, J. N., & Davis, D. E. (2013). Defensive religion as a source of meaning in life: A dual mediational model. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(3), 227–232.

Van Tongeren, D. R., Green, J. D., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., & Hulsey, T. L. (2016). Prosociality enhances meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048814.

Williamson, P. W., Hood, R. W., Ahmad, A., Sadiq, M., & Hill, P. C. (2010). The Intratextual fundamentalism scale: Cross-cultural application, validity evidence, and relationship with religious orientation and the big 5 factor markers. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 13(7–8), 721–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670802643047.

Wnuk, M., & Marcinkowski, J. T. (2014). Do existential variables mediate between religious-spiritual facets of functionality and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9597-6.

Wong, Y. J., Rew, L., & Slaikeu, K. D. (2006). A systematic review of recent research on adolescent religiosity/spirituality and mental health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840500436941.

Worthington Jr, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., ... O'Connor, L. (2003). The religious commitment inventory--10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.84.

Yildiz, M. (2018). Reflections on gender discrimination in the spiritual life of a Muslim community. In M. de Souza & A. Halafoff (Eds.), Re-enchanting education and spiritual wellbeing (pp. 149–160). Routledge.

You, S., & Lim, S. A. (2019). Religious orientation and subjective well-being: The mediating role of meaning in life. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 47(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091647118795180.

Zhang, Z. (2014). Monte Carlo based statistical power analysis for mediation models: Methods and software. Behavior Research Methods, 46(4), 1184–1198.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (College Research Ethics Sub-committee) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual study participants. For participants who were under 18 of age, parental consents were also collected beforehand.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, A.Y.C., Liu, J.K.K. Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity on well-being through meaning in life and its gender difference among adolescents in Hong Kong: A mediation study. Curr Psychol 42, 7171–7181 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02006-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02006-w