Abstract

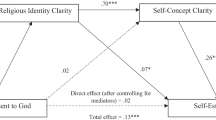

The present study concerns the relationship between self-concept clarity, religiosity, and well-being, as well as the mediating influence of religiosity on the relationship between self-concept clarity and sense of meaning in life and self-esteem. Self-concept clarity was found to be a significant predictor of sense of meaning in life and self-esteem; intrinsic religious orientation was found to be a predictor of sense of meaning in life, while the quest religious orientation was a predictor for self-esteem. The cross-products of self-concept clarity and intrinsic religious orientation were found to be related to the sense of purpose in life, which would point to religiosity being a mediator of the relationship between self-concept clarity and sense of purpose in life. The cross-products of self-concept clarity and quest religious orientation were found to be a predictor of self-esteem, which indicates a mediating effect of this religious orientation in the relationship of self-concept clarity and self-esteem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The current study is an attempt to merge research on two different paths leading to higher well-being. There is substantial evidence that people’s religiousness is related to positive mental and subjective well-being. On the other hand, the psychologic trait of self-concept clarity has been shown to be linked to self-esteem, perceived meaning in life and other positive mental outcomes. Agreeing with Jones (2004) that presence of mediating factors helps us understand more precisely the ways in which religion actually does impact on human life (p. 317), we aimed to investigate interactions between self-concept clarity and religious orientations. In particular, we were interested if those interactions are significant predictors of meaning in life and self-esteem and if high religiosity is related to different levels of purpose in life and self-esteem among people with high and low self-concept clarity.

Self-Concept Clarity and Well-Being

The self-concept clarity (SCC) idea was first introduced by Campbell (1990). The author defines self-concept clarity as the extent to which the contents of one's self-beliefs are clearly and confidently defined, internally consistent, and temporally stable. Research shows that a high level of self-concept clarity is positively related to mental health. For example, Campbell et al. (1991) showed a relationship between self-concept clarity and self-esteem. People with high self-esteem are found to be more certain about their own attributes. People with low self-esteem did not have a well-defined, clear and not even a negative self-image, i.e., their self-beliefs seemed to be more neutral and relatively uncertain, unstable, and inconsistent, such that they tended to be less certain about their own attributes than certain about having negative ones. The relationship between low self-esteem and unclear self-knowledge appears to be based on a feedback mechanism. Low self-esteem mediates diverse information about oneself, which causes low clarity. That, in turn, makes one more prone to outside influence, which can lower self-esteem (Campbell et al. 1996). Also, previous research conducted on Polish samples confirmed a positive relationship of self-concept clarity and mental health. It was demonstrated that people with lower self-concept clarity agree more with statements that life has no meaning and that they have no control over life. People with lower self-concept clarity were also less prone to delay gratification (Błażek 2008).

Religiousness and Well-Being

A number of research results show a positive relationship between religiosity and well-being, mental health, self-esteem, and meaning in life (e.g. McCullough and Willoughby 2009; Pargament 2002; Powell et al. 2003). To be more specific, meta-analysis conducted by Witter et al. (1985) revealed that religiousness was positively associated with subjective well-being (weakly but significantly with mean effect size of r = .16). Some of the measures and forms of religiousness were positively associated with well-being [e.g. a negative relationship between intrinsic religiousness and depressive symptoms (Smith et al. 2003) or a positive relationship between benevolent religious reappraisals of stressors and collaborative religious coping with satisfaction with life and happiness (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005)]. On the other hand, some forms of religiousness are negatively related to well-being (e.g. extrinsic religiousness is associated with poorer mental health and depressive symptoms; see Smith et al. 2003).

Recently, Steger and Frazier (2005) conducted two studies and found that meaning in life mediated the relation between religiousness and life satisfaction as well as the relationship between religious behaviors and well-being. Authors concluded that “religious individuals might feel greater well-being because they derive meaning in life from their religious feelings and activities” (see Steger and Frazier 2005 p. 579).

The limitations of this paper’s length do not allow for a proper overview of the research conducted on the relationship between different forms of religiosity and the quality of life, but they are widely presented and discussed (e.g. Genia 1996; George et al. 2000; Krause 2009; Lavric and Flere 2008; Marks 2005; McCullough and Willoughby 2009; Pargament 2002; Smith et al. 2003).

The Present Research

The present study intends to investigate the interactions between the above mentioned paths to higher well-being. We hypothesized that religiousness will moderate the relationship between self-concept clarity and well-being. We decided to use scales that measure four widely known religious orientations: intrinsic religious orientation, extrinsic religious orientation, quest religious orientation, and religious fundamentalism. As for the measures of well-being, the self-esteem scale and scale measuring purpose in life were used. Both self-esteem and the perceived meaning of one’s life are commonly considered good indicators of positive mental health and fundamental aspects of optimal human functioning (e.g. Diener and Diener 1995; Ryff 1989; Ryff and Singer 1998).

Based on previous research, we expected that the relationship between religiosity, meaning in life and self-esteem will only be visible among people with low self-concept clarity. High self-concept clarity brings a lot of positive mental health outcomes by itself (Campbell et al. 1991, 1996) so a possible “extra” positive influence of religiosity among the people with high self-concept clarity should be lower and more blurred. This prediction is consistent with Campbell’s (1990) suggestion that individuals with low self-concept clarity should be more influenced by external factors. That is, individuals with less clearly defined self-believes are more prone to seek external sources to help them characterize themselves. Internalization of religious values, beliefs, and standards of proper behavior could facilitate their attempts to build stable and internally consistent identities.

To be precise, we predicted that, especially among people with low self-concept clarity, the religious orientations considered to be more mature and based on treating religion as a force organizing one’s life (intrinsic and quest religious orientations) will be related to higher sense of meaning in life and higher self-esteem than among people with low intrinsic and quest religious orientation. Extrinsic religiousness is generally associated with poorer mental health (Smith et al. 2003). In this case, a higher level of extrinsic religious orientation should be related to negative life evaluation (lower level of perceived purpose in life) and a lower self-esteem. Since the research on the relationship between religious fundamentalism and well-being is quite limited, we made no assumptions for this religious orientation.

Previous studies showed that anxiety is strongly and negatively related to self-esteem, purpose in life and general well-being (e.g. Bogels and Mansell 2004; de Jong 2002; Shek 1993). Based on that research, we also included an anxiety scale so as to control the influence of anxiety upon the relationships among the variables we found interesting.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A sample consisting of parents and relatives of psychology students from one of the major Polish universities was researched. The students were asked to give the questionnaires to their parents or adult members of their families (procedure successfully used previously, e.g. Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992). The number of participants was 197.

As most measures of religious orientation we have applied (excluding the religious fundamentalism scale) were developed for use with people from Christian backgrounds (Batson et al. 1993), non-believers and people from other religious traditions (e.g. Buddhism) were counted out. One hundred and seventy-nine participants were considered (141 women); 166 of them self-identified as Catholic, 7 as Protestant and 6 people described their beliefs as based on a Christian background (for example, brought up in a Christian family). All of the participants were Caucasian. Average age of the participants was 38 (SD = 12.7).

Measures

Purpose in Life scale (PIL; Crumbaugh and Maholick 1964). The PIL is a 20-item measure of existential meaning and purpose in life perceived by an individual. Each response is scored on a 7-point scale (e.g., “My personal existence is…”; 1 = utterly meaningless and without purpose to 7 = very purposeful and meaningful). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al. 1983). The instruction for the 20 trait-anxiety items requires respondents to report how often they have generally experienced anxiety-related feelings. This inventory is widely used by professionals studying relationship between religion and psychologic well-being. In the current study, internal consistency reliability was .89.

Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCCS; Campbell 1990). The Self-Concept Clarity scale is a 12-item self-report measure (e.g. “In general, I have a clear sense of who I am and what I am”; “Sometimes I feel that I am not really the person that I appear to be” and “My beliefs about myself often conflict with one another”) that proved to be reliable and valid, with an average Cronbach’s alpha of .86 across various samples (Campbell et al. 1996). The scale has been adapted to different cultures [e.g. Estonian version of the SCC scale (Matto and Realo 2001) and German version (Stucke and Sporer 2002)] and has been used in different psychologic domains: from investigation of the relationship among self-concept clarity, aggression, and narcissism (Stucke and Sporer 2002) through the study of the gender differences in self-focused attention (Csankl and Conway 2004) to the research on internalization of societal standards and on body image (Vartanian 2009). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was: .87.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES; Rosenberg 1965).This commonly used questionnaire assesses level of self-esteem on 10-item Likert-type scale and taps generalized, global feelings of self-worth. In the current study, internal consistency reliability was .70.

Religious Fundamentalism Scale (RFS; Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992). This 20-item scale was designed to measure religious fundamentalism across a variety of religious affiliations: Hindu (α = .91), Muslim (α = .94), Jewish (α = .85), and Christian (α = .92) (Hunsberger 1996). Religious fundamentalism is defined by Altemeyer and Hunsberger (1992) as the belief that “there is one set of religious teachings that clearly contains the fundamental, basic, intrinsic, essential, inerrant truth about humanity and deity; that this essential truth is fundamentally opposed by forces of evil which must be vigorously fought; that this truth must be followed today according to the fundamental, unchangeable practices of the past; and that those who believe and follow these fundamental teachings have a special relationship with the deity”. In the current study, internal consistency reliability was .87.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic religious orientations scale (I and E; Allport and Ross 1967). According to Allport, intrinsic religious orientation defines the kind of religious faith that is professed as an aim in itself. People who have high level of intrinsic religious orientation treat their faith as the main force motivating them and organizing their lives. Extrinsic religious orientation defines an instrumental approach toward religion and is used for fulfilling other needs (for example, need for belonging, power, and control). Research on Allport’s idea showed a number of interesting relations between religiosity and other psychologic variables. For example, intrinsic religious orientation turned out to be related, among other things, to lower fear of death level, perceived sense of meaning in life and inner locus of control, while extrinsic religious orientation is related to higher fear of death level and to a sense of helplessness (see research overview: Donahue 1985). Cronbach’s alphas in the current study were .82 for I; .51 for E [internal consistency reliability was not satisfying for external religious orientation, but consistent with other Polish studies (e.g., .56 in Socha 1999); the consistency problem of E scale seems to have been caused by specificity of Polish samples, (see Socha 1999 for discussion), or even more generally by specificity of non-Protestant samples in Europe (see Flere et al. 2008)].

Quest religious orientation scale (Q; Batson 1976; Batson et al. 1993). Quest religious orientation is a concept first introduced by Batson, which aimed at completing the intrinsic—extrinsic classification introduced by Allport. According to Batson, quest religious orientation describes religiosity that is mature, open to new experiences and religious doubt and looks for more complete answers to the questions asked by life. It is also characterized by skepticism, self-criticism, and complexity in thinking about existential issues. (Batson and Raynor-Prince 1983). In the current study, internal consistency reliability was .72.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses indicated significant gender differences on self-concept clarity [t (177) = 2.34, P < .05] and trait-anxiety [t (177) = 2.44, P < .05], with men scoring higher than women on SCC scale (78.4 vs. 73.8, respectively) and lower on trait-anxiety scale (37.4 vs. 41, respectively). Two other gender differences did not reach conventional level of statistical significance, but revealed statistical tendencies: men scoring higher than women on self-esteem scale [30.7 vs. 29.6, respectively; t (177) = 1.84, P = .067], and PIL scale [115.3 vs. 111.3, respectively; t (177) = 1.66, P = .098]. There were no differences between men and women on any of the religious scales.

Zero-order correlation analyses indicated relationship between intrinsic religious orientation and religious fundamentalism; extrinsic and quest religious orientation and self-concept clarity; between self-esteem and religious fundamentalism; quest religious orientation and self-concept clarity (see Table 1).

Religiosity, Self-Concept Clarity, and Purpose in Life

To indicate if self-concept clarity and religious orientations are in fact significant predictors of perceived meaning in life and whether these relationships are moderated by interaction between those variables, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted.

Age, sex, level of education (dummy-coded, higher education = 1), religious orientations, trait anxiety, and self-concept clarity (SCC) were entered in the first step. The cross-products of SCC × RF, SCC × I, SCC × E and SSC × Q were entered in the second step. The cross-products of SCC × I, SCC × E contributed significantly to the prediction of meaning in life (see Table 2). Therefore, the hypothesis that the relationship between self-concept clarity and meaning in life is moderated by intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientations was supported.

Regression on PIL

In order to look thoroughly at statistically significant interactions between SCC × I and SCC × E, a two-way univariate ANOVA in quasi-experimental design was conducted with the religious orientation (two levels: low vs. high) and the self-concept clarity (two levels: low vs. high) entered as fixed factors. People who scored high on religiosity dimensions and SCC were in the first tercile, and people with low results were in the third tercile. People with average results were not considered in calculations. The results of ANOVA analysis of variance are shown in Fig. 1.

The significant effects that emerged were main effects of intrinsic religious orientation and self-concept clarity as well as interaction effect SCC × I. A main effect of the SCC emerged, such that participants with higher clarity of self-concept perceived life as more meaningful than participants with low clarity of self-concept F (1, 80) = 24.954, P < .001, ή² = .24. Main effect of the intrinsic religious orientation emerged as well, with more religious participants declaring more purpose and meaning in life than less religious participants F (1, 80) = 3.699, P = .058, ή² = .04. The interaction between the two factors was also significant F (1, 80) = 5.581, P < .05, ή² = .06 (Fig. 2).

Follow-up analyses revealed that higher level of intrinsic religious orientation is related to higher level of sense of meaning and sense of purpose in life only among participants with low self-concept clarity [t (36) = 2.69, P < .05 (M = 110.8 for high I group, 99.5 for low I group)]. Among participants with high self-concept clarity, no differences emerged in the level of self-esteem between the group scoring high on I scale (M = 118.6) and in the group scoring low on I scale (M = 119.3; t (44) = .20, ns).

The performed analyses show that the level of intrinsic religious orientation is not related to the differences in level of sense of meaning in life among participants with high self-concept clarity. Those participants perceive life as meaningful and worth living, regardless of whether they are very religious or not. However, among participants with low self-concept clarity, there are differences in perceiving the meaningfulness of life between participants scoring high and low on I scale. In this case, high level of religiosity is related to lower feeling of meaninglessness in life and average scores on PIL scale. At the same time, low level of religiosity among participants with low self-concept clarity is related to the lowest scores on PIL scale.

The results of univariate ANOVA in quasi-experimental design 2 (low vs. high extrinsic religiosity) × 2 (low vs. high self-concept clarity) were found to be less straightforward. Two main effects emerged: the effect of self-concept clarity F (1, 75) = 23.437, P < .001, ή² = .24, indicating that participants who have more consistent and specified self-beliefs show a higher sense of purpose for their own lives. The second effect of extrinsic religious orientation F (1, 75) = 5.096, P < .05, ή² = .06, indicating that the lower level of extrinsic religious orientation is related to higher sense of purpose in life.

The interaction between the threat and extrinsic religiosity did not reach significance. Follow-up analyses, however, supported our hypothesis about negative effects of extrinsic religiosity (statistical tendency level). High level of extrinsic religious orientation among participants with low self-concept clarity was related to higher level of sense of meaninglessness in life [t (36) = 1.908, P = .064 (M = 99.2 for high E group, 108.5 for low E group)]. Among participants with high self-concept clarity, no differences were found in the assessment of sense of purpose in life between the group scoring high on E scale (M = 116.2) and the group scoring low on E scale (M = 120.3; t (39) = 1.223, ns).

The results of analyses suggest that people with low self-concept clarity, who try to specify their identity by an instrumental approach to religion (the indicator of which is the extrinsic religious orientation), worsen the assessment of the worthiness of their life and show lower level of its purpose than people showing the low level of extrinsic religious orientation. This result is opposite to the results of analyses of relationship between intrinsic religious orientation and the sense of meaning in life. Thus, it is possible that strong but not internalized religious engagement—the one that does not shape one’s attitudes and behaviors and serves only to solve current problems and difficulties—worsens the assessment of one’s own life instead of improving it.

Religiosity, Self-Concept Clarity, and Self-Esteem

Analogous to the first hierarchical regression analyses, the second regression analyses were conducted to indicate whether self-concept clarity and religious orientations are predictors of self-esteem and whether the relationship between SCC and self-esteem is moderated by religious orientations.

Age, sex, level of education (dummy-coded, higher education = 1), religious orientations, trait anxiety, and self-concept clarity were entered in the first step. The cross-products of SCC × RF, SCC × I, SCC × E and SSC × Q were entered in the second step.

Regression on Self-Esteem

In the first step, the strong predictors of self-esteem turned out to be trait anxiety, self-concept clarity, and quest religious orientation. Those three variables explained the 49% of self-esteem variation, which in social sciences is a very strong relationship. After introducing the interactive factors, the quest religious orientation was no longer the significant predictor. At the same time, as the statistical tendency the cross-product of SCC × Q turned out to be the significant one. The strong predictability power of trait anxiety and self-concept clarity could influence the fact that the product of interaction SCC × Q did not reach the conventional level of significance (by suppressing the more subtle and not such strong relations of other variables with self-esteem). Therefore, we decided to act in a similar way to what we did in previous analyses regarding the sense of meaning in life. In order to have a closer look at the interaction of SCC × Q, a two-way univariate ANOVA in quasi-experimental design was conducted with the quest religious orientation (two levels: low vs. high) and the self-concept clarity (two levels: low vs. high) entered as fixed factors.

Similar to the previous ANOVA analyses, participants with high scores on religiosity scales and SCC positioned themselves in the first tercile and participants with low scores in the third tercile. Participants with average scores were not considered in the calculations. The results of analyses of univariate ANOVA are shown in Fig. 3.

The main effect of self-concept clarity emerged as significant, i.e. participants indicating higher level of confidence toward one’s own traits and attributes showed higher self-esteem in comparison with participants with low self-concept clarity F (1, 77) = 46.018, P < .001, ή² = .37.

The expected interaction between SCC and Q variables did reach significance as well. F (1, 77) = 4.995, P < .05, ή² = .06. Follow-up analyses revealed that higher level of quest religious orientation is related to higher self-esteem only among participants with high self-concept clarity [t (45) = 2.225, P < .05 (M = 33.19 for high Q group, 31.35 for low Q group)]. This kind of relation does not exist among participants with low self-concept clarity [t (32) = .958, ns (M = 27.16 for high Q group, 28.13 for low Q group)].

This result is not in accordance with our expectations. Those expectations concentrated on the relation of religiosity with self-esteem among people having problem with precise, clear, and consistent self-definition. The emerged relationship indicates that among people who can clearly define their own traits and attributes, the increased existential quest and religious openness booster even more their self-esteem compared to people not so open to new religious experience.

General Discussion

The strong predictors of meaning in life turned out to be trait anxiety and self-concept clarity. The only measure of religiosity that proved to be significant—with other variables controlled—was the intrinsic religious orientation. The significance of interaction I × SCC suggests that I is a moderator of the relation between self-concept clarity and the sense of meaning in life. Why do people who show higher level of intrinsic religious orientation and at the same time higher uncertainty regarding self-concept assess their lives as more meaningful and with a purpose in comparison with people less religious? It seems that due to the lack of a strong “internal steersman/guide” people with low self-concept clarity take clues on the rules of social interactions from “outside”. People with low self-concept clarity—who are at the same time religious and consider their religion an aim in itself (high level of intrinsic religious orientation)—can take guidance from their faith on how to act and organize their lives. They live their religion (Allport and Ross 1967). This allows them to regain a certain level of cognitive control over the environment and in the end on average scores on the PIL scale. People with low self-concept clarity who do not show strong intrinsic religious orientation do not have an anchor in the form of a life-organizing outlook. Therefore, they have the lowest scores on the Purpose of Life scale.

Mediation of relation SSC–PIL through extrinsic religious orientation is not so straightforward, since extrinsic religious orientation was not a significant predictor of sense of meaning in life (in step 1 in the regression analysis). However, the results of follow-up analysis show a very interesting pattern: here, opposite to intrinsic religious orientation, the higher extrinsic religious orientation is related to lower sense of meaning in life among people with low self-concept clarity.

One can argue that this results from the fact that extrinsic religious orientation represents a certain instrumental approach to religion, where faith is only a way to fulfill other needs. In a case where people uncertain of their traits, unable to clearly define their own attributes, goals and needs, at the same time, show high extrinsic religious orientation, it can turn out that this kind of approach to religion does not favor the feeling of purpose in life. Strong willingness to fulfill one’s needs through engagement in religious activities is encountered with lack of clues on how to successfully achieve that. Low self-concept clarity is related to the lack of internal clues, since the unspecified self-beliefs make it more difficult to rely on one’s own attitudes and convictions and turn one’s attention to external clues (Campbell 1990; Vartanian 2009). At the same time, a high level of extrinsic religious orientation makes it more difficult to take clues that provide normative support from one’s faith, since said faith is not considered an aim in itself and is not a life-organizing force. As Allport and Ross (1967) have shown, the Extrinsic religious orientation is a self-serving, instrumental approach to religion which is shaped to suit oneself (Donahue 1985), but when one does not know what suits him or herself best there is nothing to gain.

In conclusion, people with low self-concept clarity and high level of extrinsic religious orientation do not know what to want (they do not have clues from their self-concept) and do not know what they should want (since the uninternalized extrinsic religious orientation is not there to serve personal goals which are badly specified and inconsistent). All this can lead to those people having problems in making life plans and reaching goals that satisfy their needs, which can result in a low sense of meaning in their lives.

The significant predictors of self-esteem turned out to be self-concept clarity and quest religious orientation. Introducing the interactive factor SCC × Q led to the disappearance of a significant relationship between the quest religious orientation and self-esteem. Therefore, we can assume that Q is a mediator of the relationship between self-concept clarity and self-esteem. Cross product SCC × Q turned out to be significant only as a statistical tendency but this can result from the large percentage of variation of self-esteem explained by trait anxiety and self-concept clarity. Such a strong relation of two variables with self-esteem can suppress more subtle relations of self-esteem with other variables. However, very interesting results emerged from the follow-up analyses. Contrary to what we expected, the higher level of quest religious orientation was not related to self-esteem among people with lower self-concept clarity. Regardless of their religiosity, people with low self-concept clarity showed much lower self-esteem in comparison with people with high self-concept clarity. At the same time, among people who declared certainty about who they are and where they are headed to, the higher level of quest religious orientation was related to higher self-esteem (in comparison with people not showing any existential quest, religious openness, and readiness to religious doubt).

This result can be explained with conclusions from the theory of cognitive functioning proposed by Kruglanski et al. (1996). They distinguished two main mechanisms on which the information absorption is based: seizing and freezing. Those phases follow periodically one after another, i.e. the structure of knowledge present at the phase of seizing expands with new information and then—during the freezing phase—an attempt to restructure the existing knowledge and convictions is made in order to have the new information incorporated to cognitive structures, schemes, and plans. Said mechanism of functioning suggests that only people with stable and integrated conviction systems are ready to yet again leave the phase of freezing and open themselves to new information. This cognitive closure probably exists among people with high self-concept clarity—they are certain about their convictions and traits; they have stable opinions about themselves and are aware of the structure of their goals. In that case, repeated cognitive seizing in the context of religious life, indicated by high level of quest religious orientation, openness to new religious experience, self-criticism and not rejecting religious doubt can enrich the cognitive system and self-structures and lead to the increase of self-esteem (which results from perceiving the self as developing by gaining new experience, and thus competent). At the same time, new information is not a threat for the stable self structures, so it does not lead to unwelcome results (e.g. anxiety or decrease of self-esteem). This mechanism is less possible among people with low self-concept clarity where the cognitive structures of one’s own traits and plans are not well integrated. In that case, the reopening of cognitive structures (in the context of religious beliefs as indicated—for example—by a high quest religious orientation) should lead to opposite results: unshaped auto-stereotypes influenced by new information and critical analyses can disintegrate even further and lead to the decrease of self-esteem (which results from ego-treat and from self-perception of oneself as unable to cognitively control the environment). This effect was observed in our study: among people with low self-concept clarity, the high level of quest religious orientation was related to lower self-esteem (although the differences were not statistically significant).

Our study introduces new elements to research on religiosity: the self-concept clarity variable. The strong relationship between SCC and variables linked to well-being can lead to new research areas with questions on how religious orientations moderate relations of psychologic variables with mental well-being, self-esteem, and other desirable outcomes.

References

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.

Altemeyer, B., & Hunsberger, B. (1992). Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2, 113–133.

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 461–480.

Batson, C. D. (1976). Religion as prosocial: Agent or double agent? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 15, 29–45.

Batson, C. D., & Raynor-Prince, L. (1983). Religious orientation and complexity of thought about existential concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 22, 38–50.

Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P. A., & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the individual: A social-psychological perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Błażek, M. (2008). Zróżnicowanie w poziomie dekonstrukcji Ja osób o różnej klarowności samowiedzy w sytuacji wykluczenia społecznego. In M. Plopa & M. Błażek (Eds.), Współczesny człowiek w świetle dylematów i wyzwań: Perspektywa psychologiczna (57–68). Kraków: IMPULS.

Bogels, S. M., & Mansell, W. (2004). Attention processes in the maintenance and treatment of social phobia: Hypervigilence, avoidance and self-focused attention. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 827–856.

Campbell, J. D. (1990). Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 538–549.

Campbell, J. D., Chew, B., & Scratchley, L. S. (1991). Cognitive and emotional reactions to daily events: The effects of self-esteem and self-complexity. Journal of Personality, 59, 473–505.

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 141–156.

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20, 589–596.

Csankl, P. A. R., & Conway, M. (2004). Engaging in self-reflection changes self-concept clarity: On differences between women and men, and low- and high-clarity individuals. Sex Roles, 50, 469–480.

de Jong, P. J. (2002). Implicit self-esteem and social anxiety: Differential self-favouring effects in high and low anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 501–508.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 400–419.

Flere, S., Edwards, K. J., & Klanjsek, R. (2008). Religious orientation in three central European environments: Quest, intrinsic, and extrinsic dimensions. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 18, 1–21.

Genia, V. (1996). I, E, quest, and fundamentalism as predictors of psychological and spiritual well-being. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35, 56–64.

George, L. K., Larson, D. B., Koenig, H. G., & McCullough, M. E. (2000). Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 19, 102–116.

Jones, J. W. (2004). Religion, health, and the psychology of religion: How the research on religion and health helps us understand religion. Journal of Religion and Health, 43, 317–328.

Krause, N. (2009). Church-based social relationships and change in self-esteem over time. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48, 756–773.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychological Review, 103, 263–283.

Lavric, M., & Flere, S. (2008). The role of culture in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 47, 164–175.

Marks, L. (2005). Religion and bio-psycho-social health: A review and conceptual model. Journal of Religion and Health, 44, 173–186.

Matto, H., & Realo, A. (2001). The Estonian self-concept clarity scale: Psychometric properties and personality correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 59–70.

McCullough, M. E., & Willoughby, B. L. B. (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 69–93.

Pargament, K. I. (2002). The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 168–173.

Powell, L. H., Shahabi, L., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist, 58, 36–52.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 1–28.

Shek, D. T. L. (1993). The Chinese version of the state-trait anxiety inventory: Its relationship to different measures of psychological well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49, 349–358.

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636.

Socha, P. M. (1999). Ways religious orientations work: A Polish replication of measurement of religious orientations. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 9, 209–228.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religion to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 574–582.

Stucke, T. S., & Sporer, S. (2002). When a grandiose self-image is threatened: Narcissism and self-concept clarity as predictors of negative emotions and aggression following ego-threat. Journal of Personality, 70, 509–532.

Vartanian, L. R. (2009). When the body defines the self: Self-concept clarity, internalization, and body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 94–126.

Witter, R. A., Stock, W. A., Okun, M. A., & Haring, M. J. (1985). Religion and subjective well-being in adulthood: A quantitative synthesis. Review of Religious Research, 26, 332–342.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Błażek, M., Besta, T. Self-Concept Clarity and Religious Orientations: Prediction of Purpose in Life and Self-Esteem. J Relig Health 51, 947–960 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9407-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9407-y