Abstract

How do welfare regimes function when state institutions are weak and ethnic or sectarian groups control access to basic services? This paper explores how people gain access to basic services in Lebanon, where sectarian political parties from all major religious communities are key providers of social assistance and services. Based on analyses of an original national survey (n = 1,911) as well as in-depth interviews with providers and other elites (n = 175) and beneficiaries of social programs (n = 135), I make two main empirical claims in the paper. First, political activism and a demonstrated commitment to a party are associated with access to social assistance; and second, higher levels of political activism may facilitate access to higher levels or quantities of aid, including food baskets and financial assistance for medical and educational costs. These arguments highlight how politics can mediate access to social assistance in direct ways and add new dimensions to scholarly debates about clientelism by focusing on contexts with politicized religious identities and by problematizing the actual goods and services exchanged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In much of Latin America and East Asia, state-run welfare regimes are more articulated than in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and therefore there is less scope for parties, movements, and other non-state actors to use service provision for political goals (Haggard and Kaufman 2008). As the growing literature on patronage and clientelism in Latin America shows (Diaz-Cayeros et al. 2007; Calvo and Murillo 2004; Stokes 2005; Weitz-Shapiro 2006), parties in these regions may use discretionary access to state programs as a form of patronage, but they do not generally operate major welfare networks independently from the state.

On the latter point, see Diaz-Cayeros et al. (2007).

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this example.

Again, even in Argentina, which is the basis for many recent studies of clientelism in Latin America, parties may engage in non-electoral politics. For example, Auyero (2007) points to the actions of the Peronist party in encouraging food riots to gain or maintain support.

The socialization effect of schooling suggests that providers are most likely to both target and attract core supporters with educational programs.

In each multi-member district, a pre-established quota of seats is reserved for candidates from different sects so that the main axes of competition occur within rather than across sects. All voters, regardless of sect, vote for candidates from all sects and for as many candidates as there are seats available (IFES 2009). The district of voter registration, which is derived from the father’s (or husband’s) district of origin, does not always correspond to place of residence and, because of the sensitivity of confessional balances, it is difficult to change the district of voter registration (EU 2005).

In many French colonies, the colonial authorities established centralized state institutions with lasting legacies for post-colonial systems (MacLean 2010; Widner 1994). In Lebanon, however, the French did not establish centralized institutions, particularly in the realm of social provision, largely due to pressure from domestic commercial interests who favored a non-interventionist state (Gates 1998).

Author interviews: Sami Gemmayel, Kataeb, Bikfaya, November 9, 2007; Official, Lebanese Forces, Jel el Dib and Beirut, April 26, 2006 and January 21, 2008.

Author interviews: Official, Amal Movement, Ghobeiry, January 17, 2008; Official, Ministry of Public Health, Beirut, June 13, 2006.

In Lebanon, voters are not obliged to vote for complete party or alliance lists but politicians urge them to do so and most voters comply.

For example, parties often vary the order of candidate names on ballots distributed to different families (Author interview: Representative, Lebanese Association for Democratic Elections, Beirut, December 10, 2007).

Author interviews: Member, PSP, Beirut, October 24, 2007; Director, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (October 29, 2007; Representative, Lebanese Association of Democratic Elections, Beirut, December 10, 2007)

Author interviews: Member, PSP, Beirut, October 24, 2007; Sunni woman, Hamra, Beirut, November 22, 2007; Sunni women, Sidon, November 24, 2007; Sunni women, Verdun, Beirut, December 2, 2007; Sunni woman, Tariq el Jedideh, December 4, 2007.

With its clear and public criteria of targeting the families of martyrs with some of its social programs, Hezbollah is a partial exception (Author interview: Official, Emdad/Hezbollah, Beirut, November 2, 2007; Hamzeh 2004).

The sample was designed as a cross-section of all citizens above the age of 18 in Lebanon. I applied random selection methods at every stage of sampling (except at the household level, where the “head of household” was selected) and used sampling based on probability proportionate to population size (PPPS). The design was a stratified, multi-stage, area probability sample. Geographically defined sampling units of decreasing size were first selected and the probability of selection at various stages was adjusted as follows: the sample was stratified by province, reducing the likelihood that distinctive regions, which tend to have varied concentrations of religious or ethnic groups, were left out of the sample. Next, a PPPS procedure was used to randomly select primary sampling units in order to guarantee that more populated geographical units had a greater probability of being chosen. Households were then randomly selected within each PSU. This procedure allowed inferences to the national adult population with a margin of sampling error of no more than plus or minus 2.2% with a confidence level of 95%. The response rate for the survey was 67% (1,911 out of 2,859).

The respondents range from 18 to over 80 years of age distributed across the following age brackets: 6.5% in the 18–25 range, 9.5% in the 30–35 range, 31.1% in the 35–40, 34.9% in the 40–50 range, 13.7% in the 50–60 range, 3.7% in the 60–70 range, 0.4% in the 70–80 range, and 0.2% over 80 years old.

Socioeconomic status is measured in three different ways: household income, an index of ownership of basic household items, and an index of measures of financial hardship experienced in the 12 months prior to the survey.

National household income surveys, such as those conducted by the Ministry of Social Affairs in Cooperation with the U.N. Development Program in 1996 and in 2004 (Republic of Lebanon/UNDP 1998, 2006), collected detailed population information but only release the data at the qada or administrative district level, a relatively high level of aggregation.

The sectarian breakdown of the sample is 43% Christian, 24% Shi’i Muslim, 19% Sunni Muslim, 4% Druze, 4% Armenian, and 7% unidentified.

Of the 663 respondents who voted for or support a political party in Lebanon, approximately 25% support the Free Patriotic Movement, 15% support the Lebanese Forces, 4% support the Kataeb, 22% support the Future Movement, 20% support the Hezbollah, 8% support the Amal Movement and 8% support the PSP.

The survey included open-ended questions asking respondents to report the political or religious affiliations of health care providers, school administrations and sources of material assistance but the response rates were too low to include these questions in the analysis.

I ran additional logistic regressions with separate, dichotomous measures of the dependent variable, including food assistance or financial assistance for medical care or schooling only. The results of the models using food and medical aid as dependent variables corresponded with those of the ordinal and multinomial logits reported below. The model using educational assistance as the outcome, however, indicated a more significant relationship between political activism and this form of aid than suggested by the models below.

As robustness checks, I ran models with several alternative ways of measuring PAI. In one model, PAI was an ordinal variable derived from the log scale of PAI measured as a continuous variable. Respondents less than one standard deviation below the mean were coded as low PAI, those who were over one standard deviation higher than the mean were coded as high PAI, and the remaining interviewees were coded as medium PAI. A second specification of PAI used a simple additive index. Analyses with these alternative measures of activism yielded similar results as those reported below. Finally, I ran a series of analyses using the separate components of PAI as independent variables. For all forms of political behavior except voting for a full slate of candidates nominated by a party PAI exhibited a statistically significant relationship with the receipt of welfare, in most cases at the p < 0.01 level.

Questions about political behavior on the survey could not capture all possible forms of activism, particularly higher-risk, more politically-sensitive actions such as participation in riots or service as a militia fighter.

I selected these cut points for the three categories of respondents because the median level of PAI is approximately .6 and the vast majority of respondents exhibited PAI levels below 1.

Author interview: Representative, Lebanese Association for Democratic Elections (LADE), Beirut, December 10, 2007.

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for ownership and material need are 0.461 and 0.643, respectively.

I excluded Druze and Armenians from the sample because they are small minorities of the population. Other models not reported here included controls for partisan instead of sectarian affiliation and yielded similar results as reported below. The vast majority of supporters of sectarian parties in the sample come from the corresponding sect, ranging from the PSP support base, which is composed of almost 78% Druze, to the Amal Movement, whose supporters are all Shi’a. Co-religionists account for about 90% of supporters of both the Sunni Future Movement and Shi’i Hezbollah and about 91% of supporters of Christian parties. Levels of correlation between sectarian identity and co-religionist parties, however, are low because many people do not support parties, co-religionist or otherwise.

The measure of religious commitment is a composite index constructed from a factor score of questionnaire items indicating frequency of volunteering or attending meetings in religious community or place of work outside of religious obligations. The measure of self-reported piety is based on a question about whether the respondent considers religion to be important in her life and ranges from unimportant (1) to very important (5).

Due to political sensitivities, data on sectarian demography is only available based on voter registration records but not for actual residential patterns.

Fractionalization is defined as the Herfindahl index of heterogeneity among groups representing the “politically relevant” (Posner 2004) cleavages in the country (Shia, Sunni, Christian, Druze, Alawi, and Armenian). The fractionalization index was created using sectarian composition based on voter registration data. The formula for fractionalization in geographical zone i is

$$ {\hbox{Fractionalization}} = {1} - \sum { }{\left( {\mathop{{{S_{\rm{ki}}}}}\limits_k } \right)^{{2}}} $$where k represents sectarian groups and S ki is the proportion of the kth sectarian group in geographical zone i (Costa and Kahn 2003: 103–11).

The variables income and need were not statistically significant. This is not surprising because direct measures of household income are notoriously unreliable and many Lebanese are reluctant to admit to financial hardship. Thus, the questions about ownership patterns are likely to be more accurate gages of the socioeconomic status of respondents and their families.

I explore the organization of social welfare by different political and religious organizations in more detail elsewhere (Cammett 2010).

The predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 1.

Author interview: Director, local NGO, Beirut, June 18, 2004.

Author interview: Staff member, Hikmet Amin Hospital, Nabatiyyeh, December 11, 2007. The Nejdeh Hospital, officially named the Hikmat Amin Hospital, is run by a branch of the Lebanese Communist Party.

Author interview: Maronite man, Sour, December 22, 2007.

Author interview: Shi’i man, Bir Hassan, Chiyah, November 11, 2007.

Author interview: Sunni woman, Beirut, October 23, 2007.

Again, an analysis of the relationship between access to welfare and distinct sectarian identity is beyond the scope of this article. Cammett ( 2010) explores these and other dynamics in detail.

The predicted probabilities are based on the results of model 3.

Author interview: Doctor, NGO, Chiyah, November 6, 2007.

Author interview: Representative, Lebanese Red Cross, Beirut, December 17, 2007.

Author interview: Sunni woman, Beirut, October 23, 2007.

Author interview: Sunni woman, Beirut, November 17, 2007.

Author interview: Christian man, Beirut, November 16, 2007.

Author interview: Christian woman, Beirut, November 30, 2007.

Author interviews: Official, Lebanese Forces, Beirut, January 21, 2008; Official, National Dialogue Party, Mazraa, November 2, 2007.

References

Alesina A, Baqir R, Easterly W. Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1999;114(4):1243–84.

Ammar W. Health system and reform in Lebanon. WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office: Beirut; 2003.

Anderson B. Imagined communities. London: Verso; 1991.

Auyero J. Poor people’s politics: Peronist survival networks & the legacy of Evita. Duke University Press: Durham, NC; 2001.

Brinckerhoff D. Exploring state–civil society collaboration. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 1999;28:59–86.

Brown LD. Creating social capital: nongovernment development organizations and intersectoral problem solving. In: Powell WW, Clemens ES, editors. Private action and public goods. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1998. p. 228–44.

Calvo E, Murillo MV. Who delivers? Partisan clients in the Argentine electoral market. Am J Poli Sci. 2004;48(4):742–57.

Cammett M. Everyday sectarianism: welfare and politics in plural societies. Unpublished manuscript. Brown University: Department of Political Science 2010.

Central Intelligence Agency. Lebanon. CIA World Factbook; 2008.

Corm G. Liban: Hégémonie Milicienne Et Problème De Rétablissement De L'etat. Maghreb Machrek. 1991;131:13–25.

Corstange D. Diversity and development or fragmentation and failure? Government institutions and development in multiethnic societies. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Pol Sci, University of Michigan; 2007.

Costa D, Kahn M. Civic engagement and community heterogeneity, an economist’s perspective. Perspectives on politics. 2003;1(1):103–11.

Diaz-Cayeros A, Estevez F, Magaloni B. Strategies of vote-buying: poverty, democracy, and social transfers in Mexico. In: Dept of Pol Sci, Stanford University. Stanford, CA; 2007.

Dixit A, Londregan J. The determinants of success of special interests in redistributive politics. J Polit. 1996;58(4):1132–55.

Doumato EA, Starrett G, editors. Teaching Islam: textbooks and religion in the Middle East. Boulder: Lynne Rienner; 2006.

Easterly W, Levine R. Africa's growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1997;112:1203–50.

EU. Parliamentary elections in Lebanon. Election Observation Mission. Beirut, Lebanon; 2005.

Fawaz LT. An occasion for war: Mount Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1994.

Freedman SW, Corkalo D, Levy N, Abazovic D, Leebaw B, Ajdukovic D, et al. Public education and social reconstruction in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. In: Stover E, Weinstein HM, editors. My neighbor, my enemy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Gates CL. The merchant Republic of Lebanon: rise of an open economy. London: I.B. Tauris; 1998.

Habyarimana J, Humphreys M, Posner D, Weintein J. Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision. Am Poli Sci Rev. 2007;101(4):709–25.

Haggard S, Kaufman RR. Development, democracy, and welfare states: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2008.

Hamzeh AN. In the path of Hizbullah. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press; 2004.

Hanf T. Coexistence in Wartime Lebanon: decline of a state and rise of a nation. London: London Centre for Lebanese Studies in association with I.B. Tauris & Co.; 1993.

Hanssen J. Fin De Siecle Beirut: the making of an Ottoman provincial capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Harik JP. The public and social services of the Lebanese militias. Oxford: Center for Lebanese Studies, Oxford University; 1994. p. 1–54.

International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). The Lebanese Electoral System. IFES Lebanon Briefing Paper; March 2009.

Kaplan S. The pedagogical state: education and the politics of national culture in post-1980 Turkey. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2006.

Mainwaring S. Introduction: democratic accountability in Latin America. In: Mainwaring S, Welna C, editors. Democratic accountability in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 1–33.

Makdisi U. The culture of sectarianism: community, history, and violence in nineteenth century Ottoman Lebanon. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000.

MacLean LM. Informal institutions and citizenship in Rural Africa: risk and reciprocity in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. Cambridge: New York; 2010.

Nichter S. Vote buying or turnout buying? Machine politics and the secret ballot. Am Poli Sci Rev. 2008;102(1):19–31.

Podeh E. History and memory in the Israeli educational system: the portrayal of the Arab–Israeli conflict in history textbooks (1948–2000). Hist Mem. 2000;12:1.

Posner D. Measuring ethnic fractionalization in Africa. Am Poli Sci Rev. 2004;48(4):849–863.

Republic of Lebanon/UNDP. Map of living conditions in Lebanon, 1996. Ministry of Social Affairs and UNDP: Beirut; 1998.

Republic of Lebanon/UNDP. Map of living conditions in Lebanon, 2004. Ministry of Social Affairs and UNDP: Beirut; 2006.

Salamon LM. Partners in public service: government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1995.

Stokes SC. Perverse accountability: a formal model of machine politics with evidence from Argentina. Am Poli Sci Rev. 2005;99(3):315–25.

Stokes SC. Political clientelism. In: Boix C, Stokes SC, editors. Oxford handbook of comparative politics. Oxford: Oxford University; 2007. p. 604–27.

Tabbarah R. The health sector in Lebanon. 2000. MADMA: Beirut.

Traboulsi F. A history of modern Lebanon. London: Pluto; 2007.

US Dept. of State. Lebanon: international religious freedom in the world 2008. Available at http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2008/108487.htm. Accessed 3 Jan 2011.

Weitz-Shapiro R. Partisanship and protest: the politics of workfare distribution in Argentina. Latin Am Res Rev. 2006;41(3):122–47.

Widner J. Political reform in Anglophone and Francophone African Countries. In: Widner J, editor. Economic change and political liberalization in Sub-Saharan Africa. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1994. p. 49–79.

Acknowledgments

I thank Jennifer Lawless, Ellen Lust, Lauren Morris Maclean, Rebecca Weitz-Shapiro, two anonymous reviewers and, especially, Dan Corstange and Yen-Ting Chen for valuable feedback on drafts of this paper. Earlier versions were presented at the Middle East Studies Association 2009 annual meeting and the Seminar on Democracy and Development at Princeton University in April 2010. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

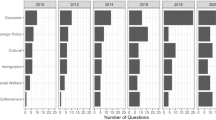

Appendix: Survey Questions

Appendix: Survey Questions

The data for the key dependent and independent variables are derived from responses to the following questions:

Dependent variables: Welfare

Food Aid:

In Lebanon, many different types of institutions provide gifts such as household supplies and baskets of food [husus ghithaiyya]. These might be voluntary organizations, religious organizations or political parties. In the past 3 years, have you received any gifts or material assistance from such organizations?

Aid for Health Care:

(Questions repeated for clinic facility attended most frequently and additional facility that respondent attended less frequently.)

Some health clinics or medical offices offer financial assistance for their services. This might be in the form of a payment waiver, reduced prices, or reimbursement for all or part of the cost. Did you receive any financial assistance from the institution you visited for these medical services?

Some governmental and non-governmental organizations provide financial assistance to help people pay for the costs of visits to the doctor. Did you receive any financial assistance from another organization to help pay for the cost of these medical services?

Aid for Education:

(Question repeated for each child below the age of 25.)

Some schools provide tuition fee waivers, reduced fees or reimbursement for all or part of school fees. Did anyone in your household receive any of these types of financial assistance from a school?

Independent variable: Political Activity Index

Volunteering and attending party meetings:

Some people volunteer or work for their preferred political party or groups associated with it, perhaps by helping out around elections, serving on committees, planning events or staffing events. Have you volunteered for or worked for a group affiliated with a political party?

If responded answered “yes” to above question:

On average in the past 12 months, how often did you attend meetings of this group?

1 = More than once per week

2 = Once per week

3 = Several times per month

4 = Once per month

5 = Several times per year

6 = Once per year or less

Did you or a member of your family volunteer or work for a political party in the 2005 National Assembly elections?

Voting behavior:

Did you vote in the 2005 National Assembly elections?

Did you vote for a complete list of candidates?

Party membership and support:

Are you a member of a political party?

Do you support a political party?

Partisan symbols and posters:

The following questions were answered by the survey enumerator after the interview:

Did the respondent’s home or attire include any political symbols or messages?

Which political party was represented in these symbols or messages?

Factor Analysis of Items in Political Activism Index

Item | Factor loading |

Volunteer for party | 0.835 |

Attended party meetings more than once per week | 0.178 |

Attended party meetings once per week | 0.369 |

Attended party meetings more than once per month | 0.273 |

Attended party meetings once per month | 0.341 |

Attended party meetings more than once per year | 0.365 |

Volunteered for the 2005 national elections | −0.048 |

Voted in the 2005 national elections | 0.313 |

Voted for the full party list | 0.355 |

Member of party | 0.664 |

Supporter of party | 0.480 |

Displays political posters at home | 0.393 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cammett, M.C. Partisan Activism and Access to Welfare in Lebanon. St Comp Int Dev 46, 70–97 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-010-9081-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-010-9081-9