Abstract

This special edition of the Review of Black Political Economics provides a contribution to the growing, vital and intellectually rich field of stratification economics. Stratification economics is an emerging field in economics that seeks to expand the boundaries of the analysis of how economists analyze intergroup differences. It examines the competitive, and sometimes collaborative, interplay between members of social groups animated by their collective self-interest to attain or maintain relative group position in a social hierarchy. The collection of articles in this volume span both quantitative and qualitative approaches, geographical distances (Bangladesh, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Kenya, and the U.S.), types of intergroup disparity (class, race, ethnicity, tribe, gender, and phenotype), and outcomes associated with social stratification (property rights in identity, human capital, financial capital, consumer surplus, health, and labor market outcomes).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, at every level of income, black and Latino households have a mere fraction of the wealth of comparable white households and these disparities grow larger at lower levels of earnings (Tippett et al. 2014).

Field experiments of employment audits provide, perhaps, the most powerful evidence that employer discrimination is a plausible explanation for racial labor market disparity. Two noted audits are those conducted by economists Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan (2004) in Chicago and sociologist Devah Pager’s (2003) audit study in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Wisconsin is a state that outlaws employer use of a criminal record for most jobs, yet, among young males of comparable race, experience, and education, Pager found that audit testers with a criminal record received half as many employment callbacks as testers without a record. Nonetheless, race was found to be more stigmatizing than incarceration. White testers with criminal records had a slightly higher callback rate than black testers without criminal records.

The Bertrand and Mullainathan study avoided the potential criticism that “tester” actors may have inadvertently signaled skills to the employers in a manner that led them to prefer the white applicants by using a “correspondence” study design. They used a double-blind strategy that avoids the use of human “testers” by attaching fictitious names, those with black and those with white sounding names, to similarly credentialed paired resumes. They found that resumes with white sounding names received a 50% higher call back rate than comparably skilled resumes with black sounding names. Perhaps even more telling, the “better” quality resumes with black sounding names received fewer callbacks than “lower” quality resumes with white sounding names.

References

Agesa J, Hamilton D. Competition and Wage Discrimination: The Effects of interindustry Concentration and Import Penetration. Soc Sci Q. 2004;85(1):121–35.

Becker GS 1971. The Economics of Discrimination. Chicago; University of Chicago Press; 1957

Bergmann BR. The Effect on White Incomes of Discrimination in Employment. J Polit Econ. 1971;79(2):294–313.

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal: A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(4):991–1013.

Blumer H. Race Prejudice As a Sense of Group Position. Pac Sociol Rev. 1958;1(1):3–7.

Darity Jr W. The Functionality of Market-Based Discrimination. Int J Soc Econ. 2001;28(10/11/12):980–6.

Darity Jr W. Stratification Economics: The Role of Intergroup Inequality. J Econ Financ. 2005;29(2):149–53.

Darity Jr W, Mason PL, Stewart JB. The Economics of Identity: The Origin and Persistence of Racial Identity. J Econ Behav Organ. 2006;60(3):283–306.

Gibson K, Darity Jr W, Samuel Jr M. Revisiting Occupational Crowding in the United States: A Preliminary Study. Fem Econ. 1998;4(3):73–95.

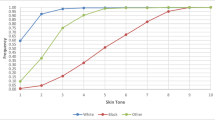

Goldsmith AH, Hamilton D, Jr WD. Shades of Discrimination: Skin Tone and Wages. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96(2):242–5.

Goldsmith A, Hamilton D, Darity Jr W. From Dark to Light: Skin Color and Wages Among African Americans. J Hum Resour. 2007;42(4):701–38.

Hamilton D. Issues Concerning Discrimination and Measurements of Discrimination in U.S. Labor Markets. Afr Am Res Perspect. 2000;6(3):116–20.

Hamilton D, Austin A, Darity W Jr. Occupational Segregation and the Lower Wages of Black Men. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper. 2011.

Mason PL. Intergenerational Mobility and Interracial Inequality: The Return to Family Values. Ind Relat. 2007;46(11):51–80.

Pager D. The Mark of a Criminal Record. Am J Sociol. 2003;108(5):937–75.

Senik C, Verdier T. Segregation, Entrepreneurship and Work Values: The Case of France. J Popul Econ. 2011;24(4):1207–34.

Stewart JB. Africana Studies and Economics: In Search of a New Progressive Partnership. J Black Stud. 2008;38(5):495–805.

Stewart JB. Stratification Economics. In the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences Farmington Hills: Cengage. 2008.

Stewart JB. Be All That You Can Be?: Racial Identity Production in the Military. Rev Black Polit Econ. 2009;36(1):51–78.

Stewart J, Coleman M. The Black Political Economy Paradigm and the Dynamics of Racial Economic Inequality. In African Americans in the U.S. Economy, Rowman and Littlechild Publishers. 2005.

Tippett RT, Jones-DeWeever A, Rockeymoore M, Hamilton D, Darity W, Jr. Beyond Broke: Why Closing the Racial Wealth Gap is a Priority for National Economic Security. Report prepared by Center for Global Policy Solutions and The Research Network on Ethnic and Racial Inequality at Duke University with funds provided by the Ford Foundation. 2014.

Uhlmann EL, Cohen GL. Constructed Criteria: Redefining Merit to Justify Discrimination. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(6):474–80.

Acknowledgments

William Darity, Jr. and Darrick Hamilton would like to acknowledge and thank the Ford Foundation for their generous support while conducting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Darity, W.A., Hamilton, D. & Stewart, J.B. A Tour de Force in Understanding Intergroup Inequality: An Introduction to Stratification Economics. Rev Black Polit Econ 42, 1–6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-014-9201-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-014-9201-2