Abstract

Background

Geographic variation and temporal trends in the epidemiology of esophageal and gastric cancers vary according to both tumor morphology and organ subsite. This study compares 1-year survival of gastric and esophageal cancers between two distinct populations: British Columbia (BC), Canada, and Ardabil, Iran.

Methods

Data for invasive primary esophageal and gastric cancer patients were obtained from the population-based cancer registries for BC and Ardabil. The relative survival rate was calculated using WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS) life-tables for each country. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare survival differences between BC and Ardabil. T-tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare patient characteristics and tumor factors between the populations.

Results

The overall 1-year age-standardized relative survivals for gastric cancer were 48% and 21% in BC and Ardabil, respectively (p < 0.01). The overall 1-year age-standardized relative survival for esophageal cancer was 33% and 17% in BC and Ardabil, respectively (p < 0.05). Overall and separately for each gender, age group, tumor location, and histology, there was greater 1-year survival of the gastric cancer patients in BC compared to Ardabil. For esophageal cancer; patients under age 65, patients with tumors in the middle or upper third of esophagus, and patients with squamous cell carcinoma had significantly better survival in BC than in Ardabil.

Conclusion

Findings of this study point to differences in disease characteristics and patient factors, not solely differences in healthcare systems, as being responsible for the survival difference in these populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Geographic variation and temporal trends in the epidemiology of esophageal and gastric cancers vary according to tumor morphology and organ subsite [1]. Both diseases are among the deadliest forms of cancer. Gastric cancer incidence and mortality have fallen dramatically over the past 70 years in western countries, but it is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide [2]. The majority of esophageal carcinoma patients in the world die within a year of diagnosis and only 8–20% are alive after 5 years [3]. Gastric and esophageal cancers are relatively infrequent in Canada, but common in Iran [4].

This study compares 1-year survival of gastric and esophageal cancers between the populations of British Columbia (BC), Canada, and Ardabil, Iran. We chose BC and Ardabil because both areas have high-quality population-based cancer registries. The BC Cancer Registry has been in existence since 1969 (www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/CancerStatistics, accessed November 4, 2009), and the Ardabil Cancer Registry is the first such registry in the Islamic Republic of Iran [5]. This study does not compare survival rates for different types of esophageal or gastric cancer within Ardabil or within BC.

Methods

Data for invasive primary esophageal and gastric cancer patients diagnosed in 2004 were obtained from the cancer registries for BC and Ardabil. For the BC registry, completeness of case ascertainment was 86.8% and completeness of other information was 99.8% [6]. For the Ardabil registry, overall completeness was 89% based on reports from pathology centers, identity information, demographic information and percentage of coded cancer cases [7]. Dates in the Ardabil registry were converted to equivalent values in the western calendar. For both registries, the topography and histology of cases were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O) [8]. Similar methods were used for the collection and classification of breast cancer data from BC and Ardabil data in an earlier report [9]. Esophageal cancers were grouped into four anatomic subsites: upper third (ICD-O codes C15.0–C15.3), middle third (C15.4), lower third and overlapping lesions (C15.5), and unknown (C15.8 and C15.9). Gastric cancers were grouped into three anatomic subsites: proximal third (i.e., cardia) in the gastroesophageal junction or upper third of the stomach (C16.0 and C16.1), distal stomach or lower two thirds of the stomach (C16.2–C16.7), and unknown or unspecified/overlapping lesion (C16.8 and C16.9). Histological categories for esophageal cancers were squamous cell carcinoma (ICD-O codes 8050–8082), adenocarcinoma (8140–8573), and others (mainly 8000–8020). Gastric cancers were categorized as diffuse or intestinal according to the Lauren classification system [10]. Diffuse gastric tumors are defined by ICD-O histology codes 8142, 8145, and 8490 [11]; other gastric tumors are defined as intestinal.

In BC, the vital status and date of death for cancer patients is routinely collected from government statistics. At least 1 year of follow-up information was available for each patient in BC. In Ardabil, information on a patient’s survival and date of death was obtained by interviewing cases or their families. Interviews were conducted by members of the Ardabil Cancer Registry whenever possible. The death registry in Ardabil was used to confirm this information and obtain data for patients who could not be interviewed. Based on this approach, 83.3% of Ardabil patients had completed 1-year follow-up information.

Survival time was defined as the time between cancer diagnosis and death. The relative survival rate [12] was calculated for various subgroups of each population using WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS) life-tables for each country [13]. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare differences in 1-year survival proportions between BC and Ardabil. T tests, chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare patient characteristics and tumor factors between the populations. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Other p values were denoted non-significant (NS).

Results

In 2004, 357 and 261 cases of gastric cancer were diagnosed in BC and Ardabil, respectively. Characteristics of the cases are summarized in Table 1. The mean ages of patients were 69.1 years in BC and 66.1 years in Ardabil (p < 0.01). Women comprised about one third of gastric cancer patients in both BC and Ardabil (NS). Approximately 34.5% of gastric cancer cases (49% of cases with known topography) in BC and 41.8% (60% of cases with known topography) in Ardabil were diagnosed with proximal disease (p < 0.05). Adenocarcinoma was the predominant histological type of gastric tumor, accounting for 87.4% and 79.7% of cases in BC and Ardabil, respectively (p < 0.01). About 16.0% of gastric tumors in BC and 30.3% in Ardabil were the diffuse type (p < 0.05).

In 2004, 232 and 124 cases of esophageal cancer were diagnosed in BC and Ardabil, respectively. Characteristics of cases are summarized in Table 2. The mean age of cases was 69.7 years in BC and 63.3 years in Ardabil (p < 0.01). Women accounted for about one third of cases in BC and half of cases in Ardabil (p < 0.01). Most tumors in BC cases were located in the lower third of the esophagus, while the lower and middle thirds of the esophagus had nearly equal incidence in Ardabil (p < 0.01). Adenocarcinoma was the leading type of tumor in BC cases (50% of all cases), while only 10% of cases in Ardabil had this histology type (p < 0.01).

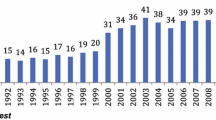

Figures 1 and 2 show the overall 1-year age-standardized relative survival of gastric and esophageal cancers in BC and Ardabil. Details of the survival rates for gastric and esophageal cancer in BC and Ardabil are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Overall and separately for each gender, age group, tumor location, and histology, there was greater 1-year survival of gastric cancer patients in BC compared to Ardabil. Patients under age 65, patients with tumors in the middle or upper third of the esophagus, and patients with squamous cell carcinoma had significantly better esophageal cancer survival in BC than in Ardabil. Table 3 shows substantial differences for age and tumor location groups within gastric cancer patients in BC that are not seen in Ardabil. In contrast, esophageal cancer patients in Ardabil had substantial survival differences for age and tumor location groups that were not meaning in BC (Table 4).

Discussion

Based on available registry and follow-up information, this study compares 1-year survival of gastric and esophageal cancer in two populations. Results indicate major differences and some interesting similarities between the populations. In general, overall 1-year relative survival was better in BC than Ardabil. There were significant differences between the populations in gastric cancer survival according to patient gender, age, tumor location, and tumor histology. For esophageal cancer; patients under age 65, patients with tumors in the middle or upper third of the esophagus, and patients with squamous cell carcinoma had significantly better survival in BC than in Ardabil. Survival differences between the populations might be based on other tumor-related factors, other patient characteristics, cancer control measures, and treatment factors.

Stage at diagnosis is likely the main tumor-related factor affecting a patient’s prognosis, and stage at diagnosis determines the course of a patient’s treatment [14]. Unfortunately, we could not include stage in our analysis because both cancer registries provided only limited information about it. Cell histology is another tumor-related factor that might affect patient survival [14]. In this study, the Lauren classification (based on tumor histology) did not have prognostic significance for 1-year survival of gastric cancer patients in either population. Several clinical studies report better survival for adenocarcinoma of esophagus [15–17], but we did not observe this. In both BC and Ardabil, tumor histology did not have a substantial influence on the survival of esophageal cancer patients. In Ardabil, tumors in the middle third of the esophagus were associated with worse survival than tumors located in the lower third. In Ardabil, the low number of cases with a tumor in the esophagus’ upper third makes it difficult to derive any meaningful conclusion concerning this group. This result is consistent with a recent report from Turkey [18]. However, results from BC and other North American studies [1, 3] indicate that survival of patients with cancers in the upper, middle, and lower third of the esophagus are similar.

Ethnicity has been suggested to be a possible prognosis factor for cancer in upper GI tract [19, 20]. BC has an ethnically diverse population. The 2006 census reported that only 52% of people living in BC at that time had a single ethnic origin [21]. In contrast, the population of Ardabil is homogeneous, with 95% being of Azeri ethnic background, which is of Aryan Caucasoid ancestry [5]. Family history also has been shown to be a prognostic factor in gastric and esophageal cancer. Gastric cancer patients with a family history of this tumor have unique clinicopathologic characteristics [22]. Poor survival among young patients from Ardabil could be explained by the presence of a higher proportion of familial cases of the disease. This is consistent with reports from other high-incidence areas [23]. Also, the high incidence of diffuse gastric cancer in the ethnically homogeneous Ardabil population is consistent with some cases having inherited mutations in the E-cadherin gene that underlie hereditary diffuse gastric cancer [24].

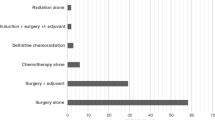

Treatment is likely to be the greatest determinant of cancer patients’ survival, and province-wide treatment guidelines in BC result in nearly uniform treatment (http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/CancerManagementGuidelines/Gastrointestinal/default.htm). Patient characteristics include inherent and demographic characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, physical performance status, comorbidity, and immune status. These variables are usually unrelated to the presence of tumor but may have a profound impact on treatment choices [18]. The general treatment for esophageal and respectable gastric cancer was surgery. Some patients also received radiation and chemotherapy depending on the stage of disease [1]. In Ardabil, guidelines do not exist and treatment is not uniform. Based on previous reports, only 28% of patients with gastric and esophageal cancer in Ardabil received curative resectional surgery and about 25% of patients did not receive any treatment [25].

This study does not compare the distribution of patient/tumor characteristics within either the BC or Ardabil population, but it is obvious that the distributions are different. One of the interesting differences between BC and Ardabil is the survival pattern for proximal and distal gastric cancers. In BC, patients with proximal gastric tumors had poorer survival than patients with distal ones. In Ardabil, there was very little difference between survival for proximal and distal gastric cancers. In BC, only about one-third of tumors occurred in the middle and upper third of the esophagus. In Ardabil, more than half of tumors with known topology were located in this anatomic region. More men than women had gastric and esophageal cancers in BC; however, the incidence of esophageal cancer in Ardabil seemed independent of gender (i.e., the same in both sexes).

The strength of this study was the availability of population-based data with details of tumor histology and pathology. This study’s limitations include the lack of complete staging information, incomplete follow-up data, and the relatively large proportion of esophageal tumors with unspecified histology. Differences in the quality of registry data between two populations could also have influenced survival comparisons. As noted in the Report of National Cancer Registration in Iran [7], there are challenges in interpreting registry information regarding the health care system in Iran. There is vast, uncontrolled population movement in and out of Ardabil, an uncoordinated medical services system, and inconsistent referrals to different centers for diagnosis and treatment [7]. It is also possible that patients with better socioeconomic status are referred to better medical facilities in central cities.

Population-based survival studies cannot assess specific treatments but can quantify the effect of cancer control measures at the population level [26]. Neither BC nor Ardabil has a screening program for gastric and esophageal cancers. In BC, these cancers are infrequent and feasibility of screening is questionable. However, Ardabil has the highest rates of gastric and esophageal cancers in the world, and a screening program should be considered.

Conclusion

Gastric and esophageal cancers are heterogeneous diseases, but they share important features. They remain clinically asymptomatic until late in the disease process with consequent poor prognoses and high mortality rates. This study points to differences in disease characteristics and patient factors, not solely differences in healthcare systems, as being responsible for the survival difference in these populations. Even so, the outcomes of these cancers are poor for both populations, and improvements in diagnosis and management are urgently needed.

Abbreviations

- ASR:

-

Age-standardized incidence rate

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- ICD-O:

-

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition

- NS:

-

Non-significant

References

Bashash M, Shah A, Hislop G, Brooks-Wilson A, Le N, Bajdik C. Incidence and survival for gastric and esophageal cancer diagnosed in British Columbia, 1990 to 1999. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:143–8.

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global Cancer Statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108.

Daly JM, Karnell LH, Menck HR. National cancer data base report on esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78:1820–8.

Sadjadi A, Nouraie M, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi-Jarrahi A, Malekezadeh R, Parkin DM. Cancer occurrence in Iran in 2002, an international perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:359–63.

Sadjadi A, Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Sepehr A, Nouraie M, Sotoudeh M, et al. Cancer occurrence in Ardabil: results of a population-based cancer registry from Iran. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:113–8.

BC cancer registry data quality, north american association of central cancer registries certification results on quality, completeness and timeliness of data by diagnosis year

Report of National Cancer Registration in Iran 2004–2005, 978 964 6570-78-8: center for disease control and prevention, ministry of health and medical education of Iran, 2006

Fritz AG. International classification of diseases for oncology: Icd-o. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Sadjadi A, Hislop TG, Bajdik C, Bashash M, Ghorbani A, Nouraie M, et al. Comparison of breast cancer survival in two populations: Ardabil, Iran and British Columbia, Canada. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:381.

Lauren P. The histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49.

Henson DE, Dittus C, Younes M, Nguyen H, Bores-Saavedra J. Differential trends in the intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in the United States, 1973–2000: increase in the signet ring cell type. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:765–70.

Black RJ, Swaminathan R, Sanaranarayanan R, Black RJ, Parkin DM. Statistical methods for the analysis of cancer survival data. Cancer survival in developing countries. Lyon: IARC; 1998.

World Health Organization WHO Statistical Information System [Internet]. World Health Organization, Geneva

Gospodarowicz M, O’Sullivan B. Prognostic factors in cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:13–8.

Siewert JR, Stein HJ, Feith M, Bruecher BL, Bartels H, Fink U. Histologic tumor type is an independent prognostic parameter in esophageal cancer: lessons from more than 1, 000 consecutive resections at a single center in the Western world. Ann Surg. 2001;234:360–7.

Alexiou C, Khan OA, Black E, Field ML, Onyeaka P, Beggs L, et al. Survival after esophageal resection for carcinoma: the importance of the histologic cell type. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1073–7.

Mariette C, Finzi L, Piessen G, Van SI, Triboulet JP. Esophageal carcinoma: prognostic differences between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:39–45.

Ugur VI, Kara SP, Kucukplakci B, Demirkasimoglu T, Misirlioglu C, Ozgen A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with stage III esophageal carcinoma: a single-center experience from Turkey. Med Oncol. 2008;25:63–8.

Gill S, Shah A, Le N, Cook EF, Yoshida EM. Asian ethnicity-related differences in gastric cancer presentation and outcome among patients treated at a Canadian cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2070–6.

Greenstein AJ, Litle VR, Swanson SJ, Divino CM, Packer S, McGinn TG, et al. Racial disparities in esophageal cancer treatment and outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:881–8.

Stats BC (2008) Ethnicity and visible minority characteristics of BC’s population, 2006–12: BC stats

Lee WJ, Hong RL, Lai IR, Chen CN, Lee PH, Huang MT. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognoses of gastric cancer in patients with a positive familial history of cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:30–3.

Wen D, Wang S, Zhang L, Zhang J, Wei L, Zhao X (2006) Differences of onset age and survival rates in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases with and without family history of upper gastrointestinal cancer from a high-incidence area in north China. Fam Cancer

Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G, Leach S, Senz J, Grehan N, et al. Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41:508–17.

Samadi F, Babaei M, Yazdanbod A, Fallah M, Nouraie M, Nasrollahzadeh D, et al. Survival rate of gastric and esophageal cancers in Ardabil province, North-West of Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10:32–7.

Sanaranarayanan R, Black RJ, Parkin DM. Cancer survival in developing countries IARC scientific publications no. 145. France: IARC; 1998.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Digestive Disease Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. MB is the recipient of a Canadian Cancer Society Research Studentship (STU-08-019764) and a Studentship from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) with the BC Cancer Foundation. AB-W and CB are MSFHR Senior Scholars.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bashash, M., Yavari, P., Hislop, T.G. et al. Comparison of Two Diverse Populations, British Columbia, Canada, and Ardabil, Iran, Indicates Several Variables Associated with Gastric and Esophageal Cancer Survival. J Gastrointest Canc 42, 40–45 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-010-9228-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-010-9228-y