Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of cadmium in concentrations relevant to those detected in human serum on cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression at mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity levels in THP-1 macrophages. Macrophages were incubated with various cadmium chloride (CdCl2) solutions for 48 h at final concentrations of 5 nM, 20 nM, 200 nM, and 2 μM CdCl2. The mRNA expression and protein levels of COXs were analyzed with RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and stable metabolite of thromboxane B2 (TXB2) concentrations in culture media were determined using ELISA method. Our study demonstrates that cadmium at the highest tested concentrations modulates COX-1 and COX-2 at mRNA level in THP-1 macrophages; however, the lower tested cadmium concentrations appear to inhibit COX-1 protein expression. PGE2 and TXB2 production is not altered by all tested Cd concentrations; however, the significant stimulation of PGE2 and TXB2 production is observed when macrophages are exposed to both cadmium and COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398. The stimulatory effect of cadmium on COXs at mRNA level is not reflected at protein and enzymatic activity levels, suggesting the existence of some posttranscriptional, translational, and posttranslational events that result in silencing of those genes’ expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

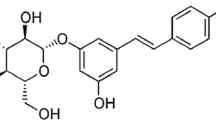

Cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are the bifunctional enzymes catalyzing the conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) in two sequential reactions, the first being the generation of prostaglandin G2 (PGG2) (cyclooxygenase reaction) followed by the reduction of PGG2 to PGH2 (peroxidase reaction). The generated PGH2 is the precursor of biologically active prostanoids such as prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) [1, 2]. COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes share 60 % identity in their amino acid sequences [3]. They exist as homodimers; each subunit consists of three domains, the epidermal growth factor domain, the membrane binding domain, and the catalytic domain containing the cyclooxygenase and peroxidase active sites [3].

COX-1, constitutively expressed in almost all cell types, but also inducible in some systems [4], was previously considered to be involved in physiological processes and playing no role in inflammation [4]. However, according to newer concept, COX-1 is also involved in inflammatory process [2, 5]; for example, COX-1 not only is responsible for the initial prostanoid response to inflammatory stimuli [6] but also contributes to the resolution of inflammation [4]. The human COX-1 gene (Ptgs1) expression is developmentally controlled and can be upregulated by tumor-promoting phorbol esters or growth factors [7]. The regulatory elements of this gene include SP1 binding site and activator protein-1 (AP-1) site [4, 7]; however, the transcriptional control of COX-1 gene expression was not well studied [7]. The products of COX-1 enzyme are thromboxane A2 (being metabolized to its stable metabolite, TXB2) and (PGE2 [6].

COX-2 is an enzyme highly inducible by pro-inflammatory cytokines, tumor promoters, mitogens, and growth factors in a variety of cell types, including monocytes [8], which results in increased prostaglandin release [5]. According to newer concept, COX-2 is the major contributor to prostanoid synthesis as inflammation progresses [6]. COX-2 gene (Ptgs2) contains several potential transcriptional regulatory elements in the 5′-flanking region: peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE), two nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) sites, one specificity protein 1 (Sp1) site, two cyclic AMP response elements (CRE), one nuclear factor for interleukin-6 expression (NF-IL6) motif, two AP-1 sites, E-box, and TATA box [4, 7, 9]. Transcriptional regulation of COX-2 gene is very complex; it can involve numerous signaling pathways, and the mechanism varies depending on the specific stimulus and the cell type [7]. The main product of COX-2 enzyme is PGE2 [6].

Cadmium is a toxic and carcinogenic heavy metal that poses nowadays a serious threat to human health because it is ubiquitously distributed in the environment and the food, tobacco smoke, and ambient air constitute the most significant sources of cadmium exposure for the general population [10, 11]. Cadmium was found to be immunomodulator; it may modify cell-mediated and humoral immune response, which may be associated with the occurrence of allergic, inflammatory diseases, and cancers [12, 13]. The target cells for heavy metals action such as cadmium are lymphocytes and macrophages, which participate in humoral immune response. As a result of toxic action of cadmium, the pro-inflammatory, pro-coagulatory, and chemotactic factors are released, activating macrophages to produce cytokines and to development of the further stages of immune reaction [12]. Cadmium was found to cause upregulation of some mediators and markers of inflammation [11]. A number of studies investigated the effect of cadmium on COX-2 mRNA [8, 14–19], protein expression [14, 16, 18, 20–25], and enzymatic activity [16–18, 24, 26, 27]. Most of them demonstrated a stimulatory effect of this metal on COX-2 in different experimental models [8, 16–19, 21–27]. However, a few reports suggested cadmium to exert either inhibitory action [14, 15] or no effect [20] on COX-2. The impact of cadmium on COX-1 was rather poorly analyzed in literature: only a few studies dealt with this issue, suggesting either no [16, 28] or stimulatory effect [17].

THP-1 cells model has some advantages over human macrophages isolated from blood of cadmium-exposed people. Their homogenous genetic background minimizes the degree of variability in the cell phenotype [29]. Such cell model eliminates the influence of other environmental factors that may interfere with the examined mechanisms of cadmium action. Therefore, THP-1 cells experimental system represents a convenient model for the studies of molecular mechanisms of cadmium action on macrophages in relation to inflammatory processes [29].

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of cadmium in low concentrations (relevant to levels detected in human serum) on activity and expression of COX-1 and COX-2.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The materials used include anti-mouse IgG FITC conjugated (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), Bakerbond columns (Witko Group, Poland), cadmium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, USA), COX-1 and COX-2 mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, Germany), FBS (ALAB, Poland), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz, Germany), Micro BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody(1:200; clone AC-74, Sigma Aldrich, Poland), nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology, USA), NS-398 (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), PBS (Biomed-Lublin, Poland), phorbol 12-myristate13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope Standards (Bio-Rad, Poland), Prostaglandin E2 EIA Kit (Cayman, USA), RNAqueous Mini Kit (Life Technologies, USA), RPMI medium (Biomed-Lublin, Poland), Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (ALAB, Poland), Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, USA), THP-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection ATCC, Rockville, USA), and Thromboxane B2 EIA Kit (Cayman, USA).

Cell Culture and Treatment

The experiments were conducted on macrophages derived from a human monocytic cell line THP-1. The differentiation of THP-1 cells into macrophages was achieved by administration of 100 nM PMA and further incubation for 24 h. The adherent macrophages were washed three times with PBS and then incubated with cadmium chloride (CdCl2) solutions for 48 h at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. The following concentrations of CdCl2 were used in this study: 5 nM, 20 nM, 200 nM, and 2 μM. They were selected based on the cadmium levels found in human serum [13]. In half of the culture dishes, the cadmium-exposed macrophages were additionally incubated with COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398 (50 μM). After 48 h, the cells were harvested by scraping and the pellets were obtained by centrifugation (800 × g, 10 min). Afterwards, the cool PBS was added to the pellets and the samples were stored at −80 °C until the following further analyses: the measurement of protein concentration using Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). The remaining supernatants were placed in new tubes and stored at −80 °C until further analyses, that is the extraction and measurement of PGE2 and TXB2 by ELISA method.

Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2 Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

The quantitative analysis of the expression of Ptgs1 and Ptgs2 genes was performed in a two-step reverse transcription PCR. Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAqueous Mini Kit (Life Technologies, USA). The quantity and quality of isolated RNA were determined using the Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA). cDNA was prepared from 400 ng of total cellular RNA in 20 μl of reaction volume, using High capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, USA) with random primers, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA), using pre-validated Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, USA) and a FAM-labeled probe for analyzed genes and a VIC-labeled probe for endogenous control gene: GAPDH, TaqMan GE Master Mix (Life Technologies, USA) and 1.5 μl of cDNA for each reaction mix of 15 μl. Every sample was analyzed simultaneously in two technical replicates; the mean C T values were used for further investigation. The relative quantification method was applied in calculations, using 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System Software (Applied Biosystems, USA). The thresholds were set manually to compare data between runs and C T values were extracted. All C T values were normalized to the mean for endogenous controls (GAPDH) for each sample. Analysis of these relative changes in gene expression between samples was performed using the 2−ΔΔC T method.

The Measurements of Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression by Western Blotting

Scraping of cells was followed by lysis using lysing buffer (protease inhibitor, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid 5 mM; Sigma Aldrich, Poland) and cell lysates were collected in −80 °C. Separation of equal amounts of protein (20 μg) was performed in 10 % sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology, USA) at 157 mA for 1.5 h at room temperature. After blocking the membrane with 5 % (COX-1) or 3 % (COX-2) non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline (Sigma Aldrich, Poland) containing 0.1 % Tween 20 (Sigma Aldrich, Poland) for 1 h at room temperature, it was incubated with primary antibodies direct against COX-1 and COX-2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) or with a monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:200; clone AC-74, Sigma Aldrich, Poland) and next with secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG HRP, 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Signals were visualized by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology, USA).

The Measurements of Prostaglandin E2 and Thromboxane B2 Concentrations

PGE2 and TXB2 were extracted from culture supernatants using Bakerbond columns (Witko Group, Poland). The measurements of PGE2 and TXB2 levels were conducted using appropriate immunoenzymatic sets (Prostaglandin E2 EIA Kit, Cayman, USA; Thromboxane B2 EIA Kit, Cayman, USA) according to manufacturers’ instruction.

Imaging of Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression

Expression of COX-1 and COX-2 proteins was examined with confocal microscopy. THP-1 macrophages were grown on cover glasses in standard in vitro culture conditions. Further, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4 % buffered formalin for 15 min in room temperature. After the fixation and washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.5 % solution of Triton X-100 in PBS. After washing with fresh portion of PBS, cells were incubated with primary antibodies: mouse anti-COX-1 and mouse anti-COX-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 1:50 dilution, in 4 °C, overnight and then washed and incubated with secondary antibody: anti-mouse IgG FITC conjugated, dilution 1:60 (Sigma-Aldrich) in antibody diluent (Dako), 30 min in room temperature and after washing with PBS further with Hoechst 33258, 30 min, room temperature. The cells were examined under a confocal microscope (FV1000 confocal with IX81 inverted microscope, Olympus, Germany); three channel acquisition and sequential scanning were used for best resolution of signal from Hoechst 33258 and FITC fluorescence. Additionally, fluorescent images were merged with transition light images.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of obtained results was conducted using Statistica 10 software (Statsoft, Poland). The results were expressed as arithmetical mean ± standard deviation (SD). The distribution of variables was evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk W test. The nonparametric tests were used for further analyses because distribution in most cases deviated from normal distribution. The results were subjected to Wilcoxon matched-pair test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Cadmium at Highest Tested Concentrations Increases Cyclooxygenase-1 mRNA Expression, While at Low Tested Concentrations Decreases Protein Expression in THP-1 Macrophages

In macrophages cultured with CdCl2, the mRNA expression of COX-1 significantly increased (35 %) (p = 0.043) for 2 μM cadmium solution (p = 0.043) (Fig. 1). Addition of NS-398 (COX-2 selective inhibitor) to cultures caused significant upregulation of COX-1 mRNA for 20 nM (p = 0.043) and 2 μM (p = 0.043) cadmium solution (29 and 84 % increase, respectively).

The effect of cadmium on COX-1 mRNA and protein expression in macrophages cultured with various cadmium solutions. a COX-1 mRNA expression following cadmium exposure without or with addition of COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398; b COX-1 protein expression (densitometric analysis of protein normalized to β-actin; c representative Western blot following cadmium exposure. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with cadmium solutions for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested by scraping and mRNA was measured by using real-time PCR method (n = 4) and protein expression by using Western blotting method (n = 3). Asterisk, statistically significant as compared with 0 nM Cd—cells incubated in RPMI medium with 10 % FBS and with DMSO addition (Wilcoxon test). Number sign, statistically significant as compared with the experiment 0 nM Cd with NS-398 (Wilcoxon test)

The estimation of the effects of cadmium on COX-1 protein expression was performed using Western blot and immunocytochemistry. The results obtained using these two methods are consistent. COX-1 protein expression decreased markedly following exposure to 20 nM (p = 0.012) and 200 nM (p = 0.012) cadmium solution (19.5 and 27 % decrease, respectively) (Fig. 1b and c). The images taken by fluorescence microscopy confirmed the influence of cadmium solution on the decrease in COX-1 protein expression (Fig. 2).

Imaging of COX-1 enzyme by fluorescence microscopy in macrophages cultured with cadmium. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with Cd solutions for 48 h. The immunohistochemistry was performed using specific primary antibody, mouse anti-COX-1 (the overnight incubation at 4 °C), and secondary antibodies conjugated with flouorochrome–anti-mouse IgG FITC (incubation for 45 min at room temperature). The nuclei of cells were DAPI stained. Image analysis was performed with a fluorescent microscope using filters 38 HE GFP for green fluorescence and 49 DAPI for blue fluorescence

Cadmium at Highest Tested Concentrations Increases Cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA Expression, While It Exerts No Effect on Protein Levels in THP-1 Macrophages

COX-2 mRNA expression increased in a cadmium concentration-dependent manner, with significant upregulation for 200 nM (p = 0.043) and 2 μM (p = 0.027) cadmium solution (18.5 and 40 % increase, respectively) (Fig. 3a). Addition of COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398 to cultures did not modulate significantly COX-2 mRNA expression at most cadmium concentrations tested; however, the interaction of cadmium at very low concentration (5 nM; p = 0.046) and NS-398 resulted in significant downregulation of COX-2 mRNA expression (p = 0.046) (22 % decrease).

The effect of cadmium on COX-2 mRNA and protein expression in macrophages cultured with various cadmium solutions. a COX-2 mRNA expression following cadmium exposure without or with addition of COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398; b COX-2 protein expression (densitometric analysis of protein normalized to β-actin; c representative Western blot following cadmium exposure. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with cadmium solutions for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested by scraping and mRNA was measured by using real-time PCR method (n = 4) and protein expression by using Western blotting method (n = 3). Asterisk, statistically significant as compared with 0 nM Cd—cells incubated in RPMI medium with 10 % FBS and with DMSO addition (Wilcoxon test). Number sign, statistically significant as compared with the experiment 0 nM Cd with NS-398 (Wilcoxon test)

The estimation of the effects of cadmium on COX-2 protein expression was performed using Western blot and immunocytochemistry. The results obtained using these two methods are consistent. Cadmium at all concentrations tested in this study did not alter significantly COX-2 protein expression (Fig. 3b and c). The images taken by fluorescence microscopy confirmed no effect of cadmium solution on COX-2 protein expression (Fig. 4).

Imaging of COX-2 enzyme by fluorescence microscopy in macrophages cultured with cadmium. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with Cd solutions for 48 h. The immunohistochemistry was performed using specific primary antibody, mouse anti-COX-2 (the overnight incubation at 4 °C), and secondary antibodies conjugated with flouorochrome–anti-mouse IgG FITC (incubation for 45 min at room temperature). The nuclei of cells were DAPI stained. Image analysis was performed with a fluorescent microscope using filters 38 HE GFP for green fluorescence and 49 DAPI for blue fluorescence

Prostaglandin E2 Production Is Unaltered by Cadmium Treatment in THP-1 Macrophages

Cadmium used in this study did not significantly affect PGE2 concentrations as compared to control (Fig. 5).

The effect of cadmium on quantity of PGE2 in culture supernatants of macrophages cultured with various cadmium solutions. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with cadmium solutions for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested by scraping and PGE2 concentration was measured by ELISA method (n = 6). Number sign, statistically significant as compared with the experiment 0 nM Cd with NS-398 (Wilcoxon test)

However, the treatment of THP-1 macrophages with both cadmium and NS-398 caused significant dose-dependent increase (262 to 488 %) in PGE2 concentration as compared to control (p = 0.027 for 5 nM; p = 0.027 for 20 nM; p = 0.043 for 200 nM; and p = 0.043 for 2 μM cadmium solutions).

Cadmium at All Tested Concentrations Does Not Significantly Affect Thromboxane A2 Production in THP-1 Macrophages

Treatment of THP-1 macrophages at 200 and 2,000 nM of cadmium resulted in insignificant decrease (19 to 41 %) in TXB2 concentrations as compared to control (Fig. 6). However, co-incubation of macrophages with cadmium and selective COX-2 inhibitor, NS-398, resulted in the opposite effect, that is increase (28 to 153 %) in TXB2 concentration, with the highest tested cadmium concentration (2 μM Cd) causing marked increase (153 %) in TXB2 level, as compared to control (p = 0.043). Addition of NS-398 to cadmium treated macrophages’ cultures caused significant increase in TXB2 production for 20 nM (p = 0.05), 200 nM (p = 0.05), and 2 μM (p = 0.043) cadmium solutions.

The effect of cadmium on quantity of TXB2 in culture supernatants of macrophages cultured with various cadmium solutions. Monocytes/macrophages were cultured with cadmium solutions for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested by scraping and TXB2 concentration was measured by ELISA method (n = 6). Number sign, statistically significant as compared with the experiment 0 nM Cd with NS-398 (Wilcoxon test)

Discussion

The current study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first such study in which the effects of very low and low concentrations of cadmium (comparable to those occurring in the blood serum of general population or occupationally exposed workers) on inflammatory enzymes such as COX-1 and COX-2 and their products were analyzed using THP-1 macrophage experimental system.

Cadmium and Cyclooxygenases mRNA Expression

We demonstrated that 48 h treatment of THP-1 macrophages with 2 μM cadmium significantly increased COX-1 mRNA expression. Similar results were reported by Miyahara et al. who showed that cadmium at 1 μM and above significantly increased the level of COX-1 mRNA in primary mouse osteoblastic cells [17]. The opposite results were reported by Figueiredo-Pereira et al.; the authors demonstrated that COX-1 gene expression was not upregulated by cadmium treatment (3–30 μM) in HT4 mouse neuronal cells [16].

The observed increased COX-1 mRNA expression due to the highest tested cadmium concentration may be explained by several mechanisms. COX-1 gene regulatory elements include three SP1 binding sites and AP-1 binding site [7]. Cadmium, in concentration range 0.5–20 μM, was found to induce the expression of c-fos and c-jun genes (genes that constitute AP-1 transcription factor) in different biological systems [30, 31]. We speculate that 48 h exposure of macrophages to 2 μM Cd might significantly activate AP-1 transcription factor, which in turn could significantly induce COX-1 gene promoter through enhanced binding AP-1 to DNA, resulting in increased COX-1 mRNA levels. Another possible mechanism responsible for increased COX-1 mRNA expression due to cadmium may be cadmium effects on secondary messengers, such as ROS or intracellular Ca2+ [10]. Although cadmium is not a Fenton metal, it causes generation of ROS; elevated levels of ROS might affect the redox-sensitive transcription factor AP-1, which could bind to appropriate COX-1 gene promoter regulatory element, and thus stimulate COX-1 mRNA expression [31]. Moreover, cadmium might activate protein kinases (such as protein kinase C) through the increased levels of intracellular Ca2+, resulting in enhanced phosphorylation of AP-1 transcription factor leading to transcriptional activation of COX-1 gene [10, 32].

Addition of NS-398 to macrophage cultures treated with cadmium resulted in significant increase in COX-1 mRNA expression (for 20 nM and 2 μM Cd). Selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 seems to enhance the stimulatory effect of cadmium on COX-1 mRNA levels.

Cadmium at concentrations 200 nM and 2 μM markedly upregulated COX-2 mRNA expression in THP-1 macrophages treated for 48 h. These results are in agreement with the results of the studies of Miyahara et al. [17], Figueiredo-Pereira et al. [16], Shin et al. [19], Seok et al. [18], and Park et al. [8]; however, it should be stressed that other experimental systems and usually higher cadmium concentrations were used by those authors. In contrast, two other studies showed the downregulation of COX-2 mRNA expression by cadmium [14, 15].

With respect to COX-2 gene transcriptional regulation, its promoter contains many cis-acting regulatory elements, of them only NF-κB site, CRE, NF-IL6 motifs, and E-box are known to be involved in the regulation of COX-2 gene expression [9, 33]. Transcription factors bind to these sites in a variety of combinations depending on cell type and also which regulatory pathway is activated [9]. Cadmium was found to activate NF-κB transcription factor [31]. We speculate that cadmium in higher tested concentrations (i.e., 200 nM and 2 μM) might cause marked upregulation of NF-κB, enhanced binding of NF-κB to COX-2 promoter, and COX-2 promoter activation leading to increased COX-2 mRNA expression. Similarly to COX-1 gene, also other mechanisms may be responsible for increased expression of COX-2 gene by cadmium, including effects on secondary messengers (ROS, intracellular Ca2+) and effects on signal transduction cascades involving kinases [10, 31]. For example, cadmium appeared to activate the following kinases: protein kinase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family (ERK, JNK, p38), stress-activated protein kinase, casein kinase 2, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II [31].

In our study, incubation of macrophages with cadmium and COX-2 selective inhibitor, NS-398, did not change significantly the COX-2 mRNA expression at most Cd concentrations tested; however, the lowest Cd concentration with NS-398 caused significant downregulation of COX-2 mRNA level. NS-398 appears to counteract the stimulatory effect of Cd on COX-2 mRNA levels. Our results seem to be in concert with the report of Callejas et al., who found that the interaction of NS-398 and LPS on COX-2 upregulation was not observed at the mRNA level [34]. In contrast to this, Blais et al. demonstrated that NS-398 enhanced the effects of LPS on transcriptional activation of key inflammatory molecules [35].

Cadmium and Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2 Protein Expression

The expression of COX-1 protein in THP-1 macrophages, as determined by Western blotting, decreased significantly following 48 h exposure to 20 and 200 nM Cd. Unfortunately, no studies have been found in the literature which dealt specifically with the effects of cadmium on COX-1 at protein level. Barrios-Rodiles et al. demonstrated that the level of COX-1 remained unaltered in PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages stimulated by other inflammatory stimulant which is LPS itself and pretreated with NS-398 [36]. Maybe the reason for the scarce of reports was the former opinion that COX-1 is a constitutive enzyme and does not change during inflammation [4]. However, this opinion appeared to be simplistic. Later on, there was suggestion that COX-1 contributes to inflammatory response [5], so the recent view is that both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes show their activities under both physiological and pathological conditions, such as inflammation [5, 6].

As mentioned previously, cadmium at concentrations 20 and 200 nM exerted inhibitory effect on COX-1 protein level in THP-1 macrophages despite the absence of alterations in COX-1 mRNA level. The observed discrepancy between COX-1 mRNA and protein levels is not unique, since Gry et al. compared mRNA and protein profiles of 1,066 gene products in 23 human cell lines and found significant correlations only in one third of examined mRNA species and corresponding proteins [37]. This rather weak correlation between COX-1 mRNA and protein levels suggests the existence of some nonspecific effect of cadmium resulting in suppression of COX-1 mRNA translation. Probably, the possible mechanisms of COX-1 protein downregulation by cadmium might involve the following: changes in its mRNA stability [9], enhanced COX-1 degradation [7], interaction with COX-1 mRNA binding proteins leading to inhibition of COX-1 protein synthesis [38], effects on translation factors [39] (for example, CdCl2 caused significant decrease in protein level of translation initiation factor 4E, eIF4E). Similar regulatory mechanisms may also be responsible for the lack of marked alterations in COX-1 protein expression due at 2 μM cadmium concentration despite significant upregulation of COX-1 mRNA levels [9, 33, 40].

In our study, the expression of COX-2 protein in THP-1 macrophages was not significantly modulated by cadmium at all tested concentrations. This result is in agreement with the results obtained by Alvarez et al. who showed that cadmium (given to rats in concentration of 15 ppm in drinking water for 3 months) did not modify the expression of COX-2 in rat prostate [20]. Ahn et al. reported even suppression of COX-2 expression induced by LPS in RAW 264.7 macrophages by cadmium [14]. However, it is worth mentioning that most of available reports demonstrated significant increase in COX-2 protein expression due to cadmium exposure [16, 18, 21–25].

The observed absence of alterations in COX-2 protein levels despite significant upregulation of its mRNA following 48 h exposure to 200 nM and 2 μM Cd remains to be elucidated. However, one must remember that the regulation of COX-2 gene expression is very complex, and this heavy metal may modulate many regulatory mechanisms that operate at different levels [30, 38]. We may not exclude cadmium-mediated suppression of COX-2 protein translation, mechanisms of which might be similar to those described by us as potential modulators of COX-1 protein translation. We speculate that the possible effects of cadmium on COX-2 protein levels might involve the following: changes in COX-2 mRNA stability [33], the effect on RNA-binding proteins [9], the effect on miRNAs [7, 41], enhanced COX-2 degradation [7, 38], the effect on translation factors [7, 39].

Cadmium and Prostaglandin E2 Synthesis by THP-1 Macrophages

Cadmium at the concentrations 5 nM–2 μM did not significantly modify the PGE2 levels in THP-1 macrophages medium following 48 h exposure. This result is in contrast to other study results which demonstrated stimulatory effect of cadmium (in general in concentrations of 1 μM and above) on PGE2 production by different cells like HT4 mouse neuronal cells [16], murine cerebrovascular endothelial cells [18], mouse osteoblasts [17, 26], neonatal mouse calvaria [27], and mouse peritoneal macrophages from cadmium-exposed mice (15 ppm Cd through drinking water for 2 months) [24].

In our study, co-incubation of macrophages with cadmium and selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 for 48 h resulted in significant dose-dependent increase in PGE2 concentration. This was an unexpected result, since previous reports showed inhibitory action of NS-398 on cadmium-stimulated PGE2 production in other cell lines [17, 27]. Maybe the increase in PGE2 levels following NS-398 treatment in cadmium-exposed macrophages was the consequence of paradoxical effect of NS-398 in our culture system and experimental conditions.

Cadmium and Thromboxane B2 Synthesis by THP-1 Macrophages

Cadmium at concentrations and exposure duration tested in our study did not significantly modulate TXB2 production by THP-1 macrophages. This result is in concert with report of Eisenmann and Miller who analyzed the effects of cadmium on human placental production of TXB2: two 12 h exposures to cadmium (40 and 100 μM) caused no significant effect on TXB2 levels [28].

The treatment of THP-1 macrophages with both 2 μM cadmium and NS-398 for 48 h resulted in increase in TXB2 concentration as compared with control. This may also be the consequence of paradoxical effect of NS-398 in our culture system. As was suggested by Ziemann et al., may be the loss of anti-inflammatory efficacy of COX-2 selective inhibitor NS-398 at higher doses occurs through paradoxical activation of NF-κB and subsequent induction of NF-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory genes [42]. Blais et al. demonstrated that COX-2 inhibition increases inflammatory response in the brain during systemic immune stimuli [35]. Gilroy and colleagues showed in carrageenan-induced inflammation model in rats that NS-398 significantly exacerbated inflammation at 48 h [43].

The fact that significantly increased COX-1 and COX-2 mRNA expression at 2 μM Cd were not accompanied with increased protein and enzymatic activity levels remains to be resolved. Sovago and Varnagy demonstrated that cadmium(II) ions may form complexes with all natural amino acids and peptides [44]. Among the most effective metal binding amino acids are cysteine, methionine, aspartic acid, and histidine [44]. Twenty-four amino acid residues were found to line cyclooxygenase active site with only one difference between COX-1 and COX-2 [45]. Maybe the lack of alterations in COX-1 and COX-2 enzymatic activities is associated with cadmium interaction with some amino acid residues that constitute the active sites of these enzymes, leading to enzyme conformational changes affecting the catalytic efficiency of cyclooxygenases through decreased substrate binding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that cadmium at the highest tested concentrations modulates COX-1 and COX-2 only at mRNA level in THP-1 macrophages; however, the lower tested cadmium concentrations appear to inhibit COX-1 protein expression. The stimulatory effect of cadmium on COXs at mRNA level is not reflected at protein and enzymatic activity levels, suggesting the existence of some posttranscriptional, translational, and posttranslational events that result in silencing of those genes’ expression.

Despite the minimal effect of cadmium on COXs found in this study, we may not exclude the possible cumulative effect of its action in such low concentrations, which will be the topic of our future research.

References

Kurumbail RG, Kiefer JR, Marnett LJ (2001) Cyclooxygenase enzymes: catalysis and inhibition. Curr Opin Struct Biol 11:752–760

Smith CJ, Zhang Y, Koboldt CM, Muhammad J, Zweifel BS, Shaffer A, Talley JJ, Masferrer JL, Seibert K, Isakson PC (1998) Pharmacological analysis of cyclooxygenase-1 in inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13313–13318

Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ (2009) Cyclooxygenases: structural and functional insights. J Lipid Res 50:S29–S34

Morita I (2002) Distinct functions of COX-1 and COX-2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 68–69:165–175

Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR (2000) New insights into the role of COX-2 in inflammation. J Mol Med (Berl) 78:121–129

Khan AA, Iadarola M, Yang HY, Dionne RA (2007) Expression of COX-1 and COX-2 in a clinical model of acute inflammation. J Pain 8:349–354

Kang YJ, Mbonye UR, DeLong CJ, Wada M, Smith WL (2007) Regulation of intracellular cyclooxygenase levels by gene transcription and protein degradation. Prog Lipid Res 46:108–125

Park YK, Hong H, Jang BC (2012) Transcriptional and translational regulation of COX-2 expression by cadmium in C6 glioma cells. Int J Mol Med 30:960–966

Harper KA, Tyson-Capper AJ (2008) Complexity of COX-2 gene regulation. Biochem Soc Trans 36:543–545

Hartwig A (2010) Mechanisms in cadmium-induced carcinogenicity: recent insights. Biometals 23:951–960

Olszowski T, Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Gutowska I, Chlubek D (2012) Pro-inflammatory properties of cadmium. Acta Biochim Pol 59:475–482

Skoczyńska A, Poreba R, Sieradzki A, Andrzejak R, Sieradzka U (2002) The impact of lead and cadmium on the immune system. Med Pr 53:259–264

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2012) Cadmium and cadmium compounds, In: Arsenic, metals, fibres and dusts. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr 100C:121–145

Ahn SI, Park SK, Lee MY, Youn HS (2009) Cadmium but not mercury suppresses NF-kappa B activation and COX-2 expression induced by Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists. Mol Cell Toxicol 5:141–146

Bernhard D, Rossmann A, Henderson B, Kind M, Seubert A, Wick G (2006) Increased serum cadmium and strontium levels in young smokers: effects on arterial endothelial cell gene transcription. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26:833–838

Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Li Z, Jansen M, Rockwell P (2002) N-Acetylcysteine and celecoxib lessen cadmium cytotoxicity which is associated with cyclooxygenase-2 up-regulation in mouse neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 277:25283–25289

Miyahara T, Tonoyama H, Watanabe M, Okajima A, Miyajima S, Sakuma T, Nemoto N, Takayama K (2001) Stimulative effect of cadmium on prostaglandin E2 production in primary mouse osteoblastic cells. Calcif Tissue Int 68:185–191

Seok SM, Park DH, Kim YC, Moon CH, Jung YS, Baik EJ, Moon CK, Lee SH (2006) COX-2 is associated with cadmium-induced ICAM-1 expression in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. Toxicol Lett 165:212–220

Shin HJ, Park KK, Lee BH, Moon CK, Lee MO (2003) Identification of genes that are induced after cadmium exposure by suppression subtractive hybridization. Toxicology 191:121–131

Alvarez SM, Gómez NN, Scardapane L, Zirulnik F, Martínez D, Giménez MS (2004) Morphological changes and oxidative stress in rat prostate exposed to a non-carcinogenic dose of cadmium. Toxicol Lett 153:365–376

Kundu S, Sengupta S, Chatterjee S, Mitra S, Bhattacharyya A (2009) Cadmium induces lung inflammation independent of lung cell proliferation: a molecular approach. J Inflamm (Lond) 6:19

Lee J, Lim KT (2011) Inhibitory effect of plant-originated glycoprotein (27 kDa) on expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in cadmium chloride-induced BNL CL.2 cells. J Trace Elem Med Biol 25:239–246

Morales AI, Vicente-Sánchez C, Jerkic M, Santiago JM, Sánchez-González PD, Pérez-Barriocanal F, López-Novoa JM (2006) Effect of quercetin on metallothionein, nitric oxide synthases and cyclooxygenase-2 expression on experimental chronic cadmium nephrotoxicity in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 210:128–135

Ramirez DC, Gimenez MS (2003) Induction of redox changes, inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 by chronic cadmium exposure in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Toxicol Lett 145:121–132

Rockwell P, Martinez J, Papa L, Gomes E (2004) Redox regulates COX-2 upregulation and cell death in the neuronal response to cadmium. Cell Signal 16:343–353

Miyahara T, Katoh T, Watanabe M, Mikami Y, Uchida S, Hosoe M, Sakuma T, Nemoto N, Takayama K, Komurasaki T (2004) Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases and protein kinase C in cadmium-induced prostaglandin E2 production in primary mouse osteoblastic cells. Toxicology 200:159–167

Romare A, Lundholm CE (1999) Cadmium-induced calcium release and prostaglandin E2 production in neonatal mouse calvaria are dependent on Cox-2 induction and protein kinase C activation. Arch Toxicol 73:223–228

Eisenmann CJ, Miller RK (1995) Cadmium and glutathione: effect on human placental thromboxane and prostacyclin production. Reprod Toxicol 9:41–48

Qin Z (2012) The use of THP-1 cells as a model for mimicking the function and regulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vasculature. Atherosclerosis 221:2–11

Luparello C, Sirchia R, Longo A (2011) Cadmium as a transcriptional modulator in human cells. Crit Rev Toxicol 41:75–82

Waisberg M, Joseph P, Hale B, Beyersmann D (2003) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cadmium carcinogenesis. Toxicology 192:95–117

Beyersmann D, Hartwig A (2008) Carcinogenic metal compounds: recent insight into molecular and cellular mechanisms. Arch Toxicol 82:493–512

Tanabe T, Tohnai N (2002) Cyclooxygenase isozymes and their gene structures and expression. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 68–69:95–114

Callejas NA, Castrillo A, Boscá L, Martín-Sanz P (1999) Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 induced by lipopolysaccharide and peroxisomal proliferators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288:1235–1241

Blais V, Turrin NP, Rivest S (2005) Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibition increases the inflammatory response in the brain during systemic immune stimuli. J Neurochem 95:1563–1574

Barrios-Rodiles M, Keller K, Belley A, Chadee K (1996) Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme activity but not mRNA expression in human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 225:896–900

Gry M, Rimini R, Strömberg S, Asplund A, Pontén F, Uhlén M, Nilsson P (2009) Correlations between RNA and protein expression profiles in 23 human cell lines. BMC Genomics 10:365

Mbonye UR, Song I (2009) Posttranscriptional and posttranslational determinants of cyclooxygenase expression. BMB Rep 42:552–560

Othumpangat S, Kashon M, Joseph P (2005) Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E is a cellular target for toxicity and death due to exposure to cadmium chloride. J Biol Chem 280:25162–25169

Dixon DA, Kaplan CD, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM (2000) Post-transcriptional control of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression. The role of the 3′-untranslated region. J Biol Chem 275:11750–11757

Fabbri M, Urani C, Sacco MG, Procaccianti C, Gribaldo L (2012) Whole genome analysis and microRNAs regulation in HepG2 cells exposed to cadmium. ALTEX 29:173–182

Ziemann C, Schäfer D, Rüdell G, Kahl GF, Hirsch-Ernst KI (2002) The cyclooxygenase system participates in functional mdr1b overexpression in primary rat hepatocyte cultures. Hepatology 35:579–588

Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willis D, Chivers J, Paul-Clark MJ, Willoughby DA (1999) Inducible cyclooxygenase may have anti-inflammatory properties. Nat Med 5:698–701

Sóvágó I, Várnagy K (2013) Cadmium (II) complexes of amino acids and peptides. Met Ions Life Sci 11:275–302

Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM (2000) Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem 69:145–182

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Olszowski, T., Gutowska, I., Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. et al. The Effect of Cadmium on COX-1 and COX-2 Gene, Protein Expression, and Enzymatic Activity in THP-1 Macrophages. Biol Trace Elem Res 165, 135–144 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-015-0234-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-015-0234-6