Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cholangiocarcinoma is an aggressive cancer with a poor prognosis and limited treatment. Gene sequencing studies have identified genetic alterations in fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) in a significant proportion of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) patients. This review will discuss the FGFR signaling pathway’s role in CCA and highlight the development of therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway.

Recent Findings

The development of highly potent and selective FGFR inhibitors has led to the approval of pemigatinib for FGFR2 fusion or rearranged CCA. Other selective FGFR inhibitors are currently under clinical investigation and show promising activity. Despite encouraging results, the emergence of resistance is inevitable. Studies using circulating tumor DNA and on-treatment tissue biopsies have elucidated underlying mechanisms of intrinsic and acquired resistance. There is a critical need to not only develop more effective compounds, but also innovative sequencing strategies and combinations to overcome resistance to selective FGFR inhibition. Therapeutic development of precision medicine for FGFR-altered CCA is a dynamic process of involving a comprehensive understanding of tumor biology, rational clinical trial design, and therapeutic optimization.

Summary

Alterations in FGFR represent a valid therapeutic target in CCA and selective FGFR inhibitors are treatment options for this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma - evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):95–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.157.

Patel N, Benipal B. Incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in the USA from 2001 to 2015: a US cancer statistics analysis of 50 states. Cureus. 2019;11(1):e3962. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3962.

Florio AA, Ferlay J, Znaor A, Ruggieri D, Alvarez CS, Laversanne M, et al. Global trends in intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma incidence from 1993 to 2012. Cancer. 2020;126(11):2666–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32803.

Banales JM, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Marzioni M, Andersen JB, Invernizzi P, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat Rev Gastroenterol &Amp; Hepatol. 2016;13:261–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.51.

Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, et al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):663–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30915-X.

Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230(6):774–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006.

Ben-Josef E, Guthrie KA, El-Khoueiry AB, et al. SWOG S0809: A phase II intergroup trial of adjuvant capecitabine and gemcitabine followed by radiotherapy and concurrent capecitabine in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2617–22. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2219.

Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, Werner M, Weimann A, Pichlmayr R. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):947–54. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.947.

Alabraba E, Joshi H, Bird N, Griffin R, Sturgess R, Stern N, et al. Increased multimodality treatment options has improved survival for hepatocellular carcinoma but poor survival for biliary tract cancers remains unchanged. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2019;45(9):1660–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.04.002.

Mavros MN, Economopoulos KP, Alexiou VG, Pawlik TM. Treatment and prognosis for patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):565–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5137.

Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1273–81. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0908721.

Lamarca A, Palmer DH, Wasan HS, et al. ABC-06 | A randomised phase III, multi-centre, open-label study of active symptom control (ASC) alone or ASC with oxaliplatin / 5-FU chemotherapy (ASC+mFOLFOX) for patients (pts) with locally advanced / metastatic biliary tract cancers (ABC) previously-tr. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):4003. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4003.

Mody K, Kasi PM, Yang J, Surapaneni PK, Bekaii-Saab T, Ahn DH, et al. Circulating tumor DNA profiling of advanced biliary tract cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.18.00324.

Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, Barriuso J, Zhu AX. New horizons for precision medicine in biliary tract cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(9):943–62. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0245.

Administration UF and D. FDA grants accelerated approval to pemigatinib for cholangiocarcinoma with an FGFR2 rearrangement or fusion. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-pemigatinib-cholangiocarcinoma-fgfr2-rearrangement-or-fusion. Published 2020.

Sleeman M, Fraser J, McDonald M, Yuan S, White D, Grandison P, et al. Identification of a new fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR5. Gene. 2001;271(2):171–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00518-2.

Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factors: from molecular evolution to roles in development, metabolism and disease. J Biochem. 2010;149(2):121–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvq121.

Zhou Y, Wu C, Lu G, Hu Z, Chen Q, Du X. FGF/FGFR signaling pathway involved resistance in various cancer types. J Cancer. 2020;11(8):2000–7. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.40531.

Babina IS, Turner NC. Advances and challenges in targeting FGFR signalling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):318–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.8.

Katoh M. FGFR inhibitors: Effects on cancer cells, tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2016;38(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2016.2620.

Helsten T, Elkin S, Arthur E, Tomson BN, Carter J, Kurzrock R. The FGFR landscape in cancer: analysis of 4,853 tumors by next-generation sequencing. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(1):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3212.

Lowery MA, Ptashkin R, Jordan E, Berger MF, Zehir A, Capanu M, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas: potential targets for intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(17):4154–61. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0078.

Ross JS, Wang K, Gay L, al-Rohil R, Rand JV, Jones DM, et al. new routes to targeted therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas revealed by next-generation sequencing. Oncologist. 2014;19(3):235–42. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0352.

Sia D, Losic B, Moeini A, Cabellos L, Hao K, Revill K, et al. Massive parallel sequencing uncovers actionable FGFR2-PPHLN1 fusion and ARAF mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7087.

Hollebecque A, Silverman I, Owens S, Féliz L, Lihou C, Zhen H, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling and clinical outcomes in patients (pts) with fibroblast growth factor receptor rearrangement-positive (FGFR2+) cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) treated with pemigatinib in the fight-202 trial. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v276. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz247.047.

Wu YM, Su F, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Khazanov N, Ateeq B, Cao X, et al. Identification of targetable FGFR gene fusions in diverse cancers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:636–47. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0050.

Saborowski A, Lehmann U, Vogel A. FGFR inhibitors in cholangiocarcinoma: what’s now and what’s next? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920953293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835920953293.

• Goyal L, Lamarca A, Strickler JH, et al. The natural history of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-altered cholangiocarcinoma (CCA). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):e16686–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e16686This abstract discusses the clinical phenotype of CCA patients harboring FGFR alterations showing this population to more likely be younger at presentation, female, Caucasian, have normal CA 19-9 levels, relatively frequent bone metastases, and shorter duration of response on first-line chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin.

Jain A, Borad MJ, Kelley RK, Wang Y, Abdel-Wahab R, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR genetic aberrations: a unique clinical phenotype. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.17.00080.

Wang J, Xing X, Li Q, Zhang G, Wang T, Pan H, et al. Targeting the FGFR signaling pathway in cholangiocarcinoma: promise or delusion? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:175883592094094. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835920940948.

Dai S, Zhou Z, Chen Z, Xu G, Chen Y. Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs): structures and small molecule inhibitors. Cells. 2019;8(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8060614.

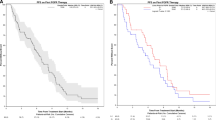

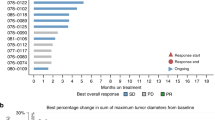

•• Abou-Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30109-1This publication shows the clinical activity and safety of pemigatinib, the first selective FGFR inhibitor approved for CCA treatment. Pemigatinib demonstrated an ORR of 36%, including 3 complete responses. All of the responses were limited to CCA patients with FGFR2 fusions. The mDOR was 9.1 months. Survival benefit was only seen in patients with FGFR2 fusions.

•• Javle MM, Kelley RK, Springfeld C, et al. A phase II study of infigratinib in previously treated advanced/metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR gene fusions/alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 3):abstrTPS356 This recently presented abstract shows the clinical activity of the selective FGFR inhibitor, infigratinib, in patients with previously treated, advanced, or metastatic CCA with FGFR alterations. Infigratinib showed an ORR of 23%, DCR of 84%, estimated mPFS of 7.3 months in patients with FGFR2 fusions. Response rates were higher in the second vs. third/later line setting, suggesting more activity in an earlier line setting.

•• Goyal L, Meric-Bernstam F, Hollebecque A, et al. Primary results of phase 2 FOENIX CCA2: the irreversible FGFR1 4 inhibitor futibatinib in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 fusions/rearrangements. In: Presentation CT010. American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; 2021. This recently presented abstract reports the activity of the covalent FGFR2 inhibitor, futibatinib (TAS-120). It demonstrated an ORR of 41.7%, DCR of 82.5%, mDOR of 9.7 months, median time to response of 2.5 months, mPFS of 9 months, and mOS of 21.7 months, though OS data is immature and ongoing.

• Park JO, Feng Y-H, Chen Y-Y, et al. Updated results of a phase IIa study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of erdafitinib in Asian advanced cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) patients with FGFR alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):4117. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4117Preliminary report of activity and safety of erdafitinib in Asian CCA patients with FGFR alterations. Among 12 patients, the ORR was 50% (60% in patients with FGFR2 fusions), DCR of 100%, and mPFS of 12.35 months.

• Mazzaferro V, El-Rayes BF, Droz Dit Busset M, et al. Derazantinib (ARQ 087) in advanced or inoperable FGFR2 gene fusion-positive intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(2):165–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0334-0Publication showing results for safety and activity of derazantinib, a non-selective inhibitor with high affinity and potent activity for FGFR 1-3 in FGFR2 fusion-positive CCA. ORR of 20.7%, DCR 82.8%, estimated mPFS 5.7 months.

O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(5):401–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028.

Wollin L, Wex E, Pautsch A, Schnapp G, Hostettler KE, Stowasser S, et al. Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1434–45. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00174914.

Bhide RS, Cai Z-W, Zhang Y-Z, Qian L, Wei D, Barbosa S, et al. Discovery and preclinical studies of (R)-1-(4-(4-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indol-5-yloxy)-5- methylpyrrolo[2,1-f][1,2,4]triazin-6-yloxy)propan- 2-ol (BMS-540215), an in vivo active potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2006;49(7):2143–6. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm051106d.

Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals I. Stivarga Prescribing Information. Whippany, NJ.; 2020.

Ohta M, Kawabata T, Yamamoto M, Tanaka T, Kikuchi H, Hiramatsu Y, et al. TSU68, an antiangiogenic receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces tumor vascular normalization in a human cancer xenograft nude mouse model. Surg Today. 2009;39(12):1046–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-009-4020-y.

Dubreuil P, Letard S, Ciufolini M, Gros L, Humbert M, Castéran N, et al. Masitinib (AB1010), a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007258.

Cheng A-L, Thongprasert S, Lim HY, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Yang TS, Wu CC, et al. Randomized, open-label phase 2 study comparing frontline dovitinib versus sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2016;64(3):774–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28600.

De Luca A, Esposito Abate R, Rachiglio AM, et al. FGFR fusions in cancer: from diagnostic approaches to therapeutic intervention. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186856.

Bolos D, Finn RS. Systemic therapy in HCC: lessons from brivanib. J Hepatol. 2014;61(4):947–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.019.

Chae YK, Hong F, Vaklavas C, Cheng HH, Hammerman P, Mitchell EP, et al. Phase II study of AZD4547 in patients with tumors harboring aberrations in the FGFR pathway: results from the NCI-MATCH trial (EAY131) subprotocol W. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(21):2407–17. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.02630.

Nogova L, Sequist LV, Perez Garcia JM, Andre F, Delord JP, Hidalgo M, et al. Evaluation of BGJ398, a fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-3 kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring genetic alterations in fibroblast growth factor receptors: results of a global phase I, dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.2048.

Administration UF and D. FDA (n.d.) grants accelerated approval to erdafitinib for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Case Medical Research. doi:10.31525/fda1-ucm635910.htm

Ochiiwa H, Fujita H, Itoh K, et al. Abstract A270: TAS-120, a highly potent and selective irreversible FGFR inhibitor, is effective in tumors harboring various FGFR gene abnormalities. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(11 Supplement):A270–0. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.TARG-13-A270.

Kalyukina M, Yosaatmadja Y, Middleditch MJ, Patterson AV, Smaill JB, Squire CJ. TAS-120 cancer target binding: defining reactivity and revealing the first fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) irreversible structure. ChemMedChem. 2019;14(4):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201800719.

Sootome H, Fujita H, Ito K, Ochiiwa H, Fujioka Y, Ito K, et al. Futibatinib is a novel irreversible FGFR 1-4 inhibitor that shows selective antitumor activity against FGFR-deregulated tumors. Cancer Res. 2020;80:4986–97. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2568.

Meric-Bernstam F, Arkenau H, Tran B, et al. Efficacy of TAS-120, an irreversible fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor, in cholangiocarcinoma patients with FGFR pathway alterations who were previously treated with chemotherapy and other FGFR inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement 5):v100. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy149.

Taiho. (n.d.) FDA grant breakthrough designation for Taiho Oncology’s futibatinib for the treatment of advanced cholangiocarcinoma. https://www.taihooncology.com/us/news/2021-04-01_toi_tpc_futibatinib_btd/.

Javle M, Lowery M, Shroff RT, Weiss KH, Springfeld C, Borad MJ, et al. Phase II study of BGJ398 in patients with FGFR-altered advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36(3):276–82. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5009.

Andrukhova O, Zeitz U, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Lanske B, Erben RG. FGF23 acts directly on renal proximal tubules to induce phosphaturia through activation of the ERK1/2-SGK1 signaling pathway. Bone. 2012;51(3):621–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2012.05.015.

Roskoski R. The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of cancers including those of the urinary bladder. Pharmacol Res. 2020;151:104567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104567.

Carr DR, Pootrakul L, Chen H-Z, Chung CG. Metastatic calcinosis cutis associated with a selective FGFR inhibitor. JAMA Dermatology. 2019;155(1):122–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4070.

van der Noll R, Leijen S, Neuteboom GHG, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Effect of inhibition of the FGFR–MAPK signaling pathway on the development of ocular toxicities. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):664–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.01.003.

Stjepanovic N, Velazquez-Martin JP, Bedard PL. Ocular toxicities of MEK inhibitors and other targeted therapies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw100.

Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas J, Huddart R, Burgess E, et al. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):338–48. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817323.

Deutsch A, McLellan BN. Severe onycholysis and eyelash trichomegaly in a patient treated with erdafitinib. JAAD case reports. 2020;6(6):569–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.013.

Bétrian S, Gomez-Roca C, Vigarios E, Delord JP, Sibaud V. Severe onycholysis and eyelash trichomegaly following use of new selective pan-FGFR inhibitors. JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153(7):723–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0500.

Aisner DL, Sholl LM, Berry LD, Rossi MR, Chen H, Fujimoto J, et al. The impact of smoking and TP53 mutations in lung adenocarcinoma patients with targetable mutations—The Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC2). Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(5):1038–47. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2289.

Canale M, Petracci E, Delmonte A, et al. Concomitant TP53 mutation confers worse prognosis in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with TKIs. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041047.

Noble MEM, Endicott JA, Johnson LN. Protein kinase inhibitors: insights into drug design from structure. Science. 2004;303(5665):1800–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1095920.

Liu Y, Shah K, Yang F, Witucki L, Shokat KM. A molecular gate which controls unnatural ATP analogue recognition by the tyrosine kinase v-Src. Bioorg Med Chem. 1998;6(8):1219–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00099-6.

Byron SA, Chen H, Wortmann A, Loch D, Gartside MG, Dehkhoda F, et al. The N550K/H mutations in FGFR2 confer differential resistance to PD173074, dovitinib, and ponatinib ATP-competitive inhibitors. Neoplasia. 2013;15(8):975–88. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.121106.

Chell V, Balmanno K, Little AS, Wilson M, Andrews S, Blockley L, et al. Tumour cell responses to new fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and identification of a gatekeeper mutation in FGFR3 as a mechanism of acquired resistance. Oncogene. 2013;32:3059–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.319.

Varghese AM, Patel JAA, Janjigian YY, et al. Non-invasive detection of acquired resistance to FGFR inhibition in patients with cholangiocarcinoma harboring FGFR2 alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):4096. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4096.

Goyal L, Saha SK, Liu LY, Siravegna G, Leshchiner I, Ahronian LG, et al. Polyclonal secondary FGFR2 mutations drive acquired resistance to FGFR inhibition in patients with FGFR2 fusion–positive cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(3):252–63. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1000.

Wu D, Guo M, Min X, Dai S, Li M, Tan S, et al. LY2874455 potently inhibits FGFR gatekeeper mutants and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Chem Commun (Camb). 2018;54(85):12089–92. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cc07546h.

•• Goyal L, Shi L, Liu LY, et al. TAS-120 Overcomes resistance to ATP-competitive FGFR inhibitors in patients with FGFR2 fusion–positive intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(8):1064–79. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0182This study demonstrates the utility of ctDNA and on-treatment tissue biopsies in evaluating the development of resistance to selective FGFR inhibitors in CCA. Emergent gate keeper mutations were detected through ctDNA while on treatment with various selective FGFR inhibitors. In vitro studies from on treatment tissue biopsies elucidated underlying mechanisms of resistance. This study also showed the activity of the covalent FGFR inhibitor futibatinib (TAS-120) in patients who developed secondary resistance to other non-covalent inhibitors.

Lau WM, Teng E, Huang KK, Tan JW, Das K, Zang Z, et al. Acquired resistance to FGFR inhibitor in diffuse-type gastric cancer through an AKT-independent PKC-mediated phosphorylation of GSK3β. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(1):232–42. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0367.

Wang X, Ai J, Liu H, Peng X, Chen H, Chen Y, et al. The secretome engages STAT3 to favor a cytokine-rich microenvironment in mediating acquired resistance to FGFR inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(3):667–79. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0179.

Krook MA, Lenyo A, Wilberding M, Barker H, Dantuono M, Bailey KM, et al. Efficacy of FGFR inhibitors and combination therapies for acquired resistance in FGFR2-fusion cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(3):847–57. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0631.

Pearson A, Smyth E, Babina IS, Herrera-Abreu MT, Tarazona N, Peckitt C, et al. High-level clonal FGFR amplification and response to FGFR inhibition in a translational clinical trial. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:838–51. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1246.

Loeuillard E, Conboy CB, Gores GJ, Rizvi S. Immunobiology of cholangiocarcinoma. JHEP Reports. 2019;1(4):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.06.003.

Thelen A, Scholz A, Benckert C, Schröder M, Weichert W, Wiedenmann B, et al. Microvessel density correlates with lymph node metastases and prognosis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(12):959–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-008-2255-9.

Shroff RT, Yarchoan M, O’Connor A, et al. The oral VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib in combination with the MEK inhibitor trametinib in advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(11):1402–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.119.

Arkenau H, Martin-Liberal J, Calvo E, et al. Ramucirumab plus pembrolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer: nonrandomized, open-label, phase I trial (JVDF). Oncologist. 2018;23:1407–e136. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0044.

Lieu C, Heymach J, Overman M, Tran H, Kopetz S. Beyond VEGF: inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor pathway and antiangiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(19):6130–9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0659.

Pepper MS, Ferrara N, Orci L, Montesano R. Potent synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189(2):824–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291x(92)92277-5.

Jang HS, Woo SR, Song K-H, Cho H, Chay DB, Hong SO, et al. API5 induces cisplatin resistance through FGFR signaling in human cancer cells. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(9):e374–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.130.

Merck. A guide to monitoring patients during treatment with Keytruda. 2017. https://www.keytruda.com/static/pdf/adverse-reaction-management-tool.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Gentry King declares that he has no conflict of interest. Milind Javle has received research funding from QED Therapeutics, Taiho Pharmceutical Group, Basilea Pharmaceutical AG, EMD Serono, Meclun, AstraZeneca, and Merck; and has received compensation for service as a consultant from QED Therapeutics, Taiho, EMD Serono, AstraZeneca, and Merck.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Evolving Therapies

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, G., Javle, M. FGFR Inhibitors: Clinical Activity and Development in the Treatment of Cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep 23, 108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01100-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01100-3