Abstract

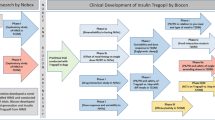

Structure-based protein design has enabled the engineering of insulin analogs with improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Exploiting classical structures of zinc insulin hexamers, the first insulin analog products focused on destabilization of subunit interfaces to obtain rapid-acting (prandial) formulations. Complementary efforts sought to stabilize the insulin hexamer or promote higher-order self-assembly within the subcutaneous depot toward the goal of enhanced basal glycemic control with reduced risk of hypoglycemia. Current products either operate through isoelectric precipitation (insulin glargine, the active component of Lantus; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) or employ an albumin-binding acyl tether (insulin detemir, the active component of Levemir; Novo-Nordisk, Basværd, Denmark). In the past year second-generation basal insulin analogs have entered clinical trials in an effort to obtain ideal flat 24-hour pharmacodynamic profiles. The strategies employ non-standard protein modifications. One candidate (insulin degludec; Novo-Nordisk a/s) undergoes extensive subcutaneous supramolecular assembly coupled to a large-scale allosteric reorganization of the insulin hexamer (the TR transition). Another candidate (LY2605541; Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) utilizes coupling to polyethylene glycol to delay absorption and clearance. On the other end of the spectrum, advances in delivery technologies (such as microneedles and micropatches) and excipients (such as the citrate/zinc-ion chelator combination employed by Biodel, Inc., Danbury, CT, USA) suggest strategies to accelerate PK/PD toward ultra-rapid-acting insulin formulations. Next-generation insulin analogs may also address the feasibility of hepatoselective signaling. Although not in clinical trials, early-stage technologies provide a long-range vision of “smart insulins” and glucose-responsive polymers for regulated hormone release.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Adams MJ, Blundell TL, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Vijayan M, Baker EN, et al. Structure of rhombohedral 2 zinc insulin crystals. Nature. 1969;224:491–5.

Blundell TL, Cutfield JF, Cutfield SM, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Hodgkin DC, et al. Atomic positions in rhombohedral 2-zinc insulin crystals. Nature. 1971;231:506–11.

Brange J, Skelbaek-Pedersen B, Langkjaer L, Damgaard U, Ege H, Havelund S, et al. Galenics of insulin: the physico-chemical and pharmaceutical aspects of insulin and insulin preparations. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987.

Dodson GG, Dodson EJ, Turkenburg JP, Bing X. Molecular recognition in insulin assembly. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:609–14.

Baker EN, Blundell TL, Cutfield JF, Cutfield SM, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, et al. The structure of 2Zn pig insulin crystals at 1.5 Å resolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1988;319:369–56.

Brange J. The new era of biotech insulin analogues. Diabetologia. 1997;40:S48–53.

Freeman JS. Insulin analog therapy: improving the match with physiologic insulin secretion. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109:26–36.

Brange J, Hansen JF, Havelund S, Melberg SG. Studies of insulin fibrillation process. In: Brunetti P, Waldhäusl WK, editors. Advanced models for the therapy of insulin-dependent diabeses. New York: Raven Press; 1987. p. 85–90.

Brems DN, Alter LA, Beckage MJ, Chance RE, DiMarchi RD, Green LK, et al. Altering the association properties of insulin by amino acid replacement. Protein Eng. 1992;5:527–33.

DeFelippis MR, Chance RE, Frank BH. Insulin self-association and the relationship to pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2001;18:201–64.

DiMarchi RD, Chance RE, Long HB, Shields JE, Slieker LJ. Preparation of an insulin with improved pharmacokinetics relative to human insulin through consideration of structural homology with insulin-like growth factor I. Horm Res. 1994;41 Suppl 2:93–6.

Heinemann L, Heise T, Jorgensen LN, Starke AA. Action profile of the rapid acting insulin analogue: human insulin B28Asp. Diabet Med. 1993;10:535–9.

Owens D, Vora J. Insulin aspart: a review. Expert Opin Drub Metabol Toxicol. 2006;2:793–4.

Barlocco D. Insulin glulisine. Aventis Pharma. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:1240–4.

Helms KL, Kelley KW. Insulin glulisine: an evaluation of its pharmacodynamic properties and clinical application. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:658–68.

Garg S, Ampudia-Blasco FJ, Pfohl M. Rapid-acting insulin analogues in Basal-bolus regimens in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:486–5.

Colquitt J, Royle P, Waugh N. Are analogue insulins better than soluble in continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion? Results of a meta-analysis. Diab Med. 2003;20:863–6.

Elleri D, Dunger DB, Hovorka R. Closed-loop insulin delivery for treatment of type 1 diabetes. BMC Med. 2011;9:120.

Schaepelynck P, Darmon P, Molines L, Jannot-Lamotte MF, Treglia C, Raccah D. Advances in pump technology: insulin patch pumps, combined pumps and glucose sensors, and implanted pumps. Diabetes Metabol. 2011;37 Suppl 4:S85–93.

Brown L, Edelman ER. Optimal control of blood glucose: the diabetic patient or the machine? Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:1–5.

NIDDK. Advances and emerging opportunities in diabetes research: a strategic planning report of the DMICC. In: Committee DMIC, editor. Washington, D.C; 2011.

ADA. American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions 2011 San Diego, California. June 24–28, 2011.

Scutcher M, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Sullivan K. Diabetic complications. In: vital biopharmaceutical insights and analytics for experts from experts. Burlington, MA: Decision Resources Group Co; 2011.

Phillips NB, Whittaker J, Ismail-Beigi F, Weiss MA. Insulin fibrillation and protein design: topological resistance of single-chain analogs to thermal degradation with application to a pump reservoir. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:277–88.

Raz I, Weiss R, Yegorchikov Y, Bitton G, Nagar R, Pesach B. Effect of a local heating device on insulin and glucose pharmacokinetic profiles in an open-label, randomized, two-period, one-way crossover study in patients with type 1 diabetes using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Clin Ther. 2009;31:980–7.

Jakobsen LA, Jensen A, Larsen LE, Sorensen MR, Hoeck HC, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Effect of cutaneous blood flow on absorption of insulin: a methodological study in healthy male volunteers. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2011;3:257–65.

Vaughn DE, Muchmore DB. Use of recombinant human hyaluronidase to accelerate rapid insulin analogue absorption: experience with subcutaneous injection and continuous infusion. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:914–21.

Nordquist L, Roxhed N, Griss P, Stemme G. Novel microneedle patches for active insulin delivery are efficient in maintaining glycaemic control: an initial comparison with subcutaneous administration. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1381–8.

Pettis RJ, Ginsberg B, Hirsch L, Sutter D, Keith S, McVey E, et al. Intradermal microneedle delivery of insulin lispro achieves faster insulin absorption and insulin action than subcutaneous injection. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:435–42.

Engwerda EE, Abbink EJ, Tack CJ, de Galan BE. Improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of rapid-acting insulin using needle-free jet injection technology. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1804–8.

Hompesch M, McManus L, Pohl R, Simms P, Pfutzner A, Bulow E, et al. Intra-individual variability of the metabolic effect of a novel rapid-acting insulin (VIAject) in comparison to regular human insulin. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:568–71.

Heinemann L, Nosek L, Flacke F, Albus K, Krasner A, Pichotta P, et al. U-100, pH-Neutral formulation of VIAject (R): faster onset of action than insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;14:222–227.

Young TS, Schultz PG. Beyond the canonical 20 amino acids: expanding the genetic lexicon. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11039–44.

Pollock RF, Erny-Albrecht KM, Kalsekar A, Bruhnand D, Valentine WJ. Long-acting insulin analogs: a review of "real-world" effectiveness in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2011;7:61–4.

King AB, Armstrong DU. Basal bolus dosing: a clinical experience. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:215–20.

Baxter MA. The role of new basal insulin analogues in the initiation and optimization of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2008;45:253–68.

Pontiroli AE, Miele L, Morabito A. Increase of body weight during the first year of intensive insulin treatment in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2011;13:1008–19.

Markussen J, Diers I, Hougaard P, Langkjaer L, Norris K, Snel L, et al. Soluble, prolonged-acting insulin derivatives. III. Degree of protraction, crystallizability and chemical stability of insulins substituted in positions A21, B13, B23, B27, and B30. Protein Eng. 1988;2:157–66.

Owens DR, Griffiths S. Insulin glargine (Lantus). Int J Pract. 2002;56:460–6.

Goykhman S, Drincic A, Desmangles JC, Rendell M. Insulin glargine: a review 8 years after its introduction. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:705–18.

Heinemann L, Linkeschova R, Rave K, Hompesch B, Sedlak M, Heise T. Time-action profile of the long-acting insulin analog insulin glargine (HOE901) in comparison with those of NPH insulin and placebo. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:644–9.

Global Diabetes Market Review 2008 & World Top Ten Diabetes drugs: World Top Ten diabetic drug brands, market trends and top companies 2008 Guild (KPG), Knol Publishing; San Francisco, California 2011. http://www.scribd.com/doc/46417074/Global-Diabetes-Market-Revi. Accessed 5 September 2012

Kohn WD, Micanovic R, Myers SL, Vick AM, Kahl SD, Zhang L, et al. pI-shifted insulin analogs with extended in vivo time action and favorable receptor selectivity. Peptides. 2007;28:935–48.

Havelund S, Plum A, Ribel U, Jonassen I, Volund A, Markussen J, et al. The mechanism of protraction of insulin detemir, a long-acting, acylated analog of human insulin. Pharm Res. 2004;21:1498–504.

Whittingham JL, Jonassen I, Havelund S, Roberts SM, Dodson EJ, Verma CS, et al. Crystallographic and solution studies of N-lithocholyl insulin: a new generation of prolonged-acting human insulins. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5987–95.

Markussen J, Jonassen I, Havelund S, Brandt J, Kurtzhals P, Hansen PH, et al.,Inventors; insulin derivatives. U. S. A. patent 6,620,780. Sept 16, 2003.

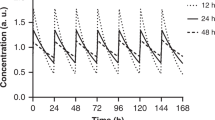

Zinman B, Fulcher G, Rao PV, Thomas N, Endahl LA, Johansen T, et al. Insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin, once a day or 3 times a week vs insulin glargine once a day in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 16-week, randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:924–31.

Birkeland KI, Home PD, Wendisch U, Ratner RE, Johansen T, Endahl LA, et al. Insulin degludec in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial of a new-generation ultra-long-acting insulin compared with insulin glargine. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:661–5.

Heise T, Tack CJ, Cuddihy R, Davidson J, Gouet D, Liebl A, et al. A new-generation ultra-long-acting basal insulin with a bolus boost compared with insulin glargine in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:669–74.

• Heller S, Buse J, Fisher M, Garg S, Marre M, Merker L, et al. Insulin degludec, an ultra-longacting basal insulin, vs insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 1 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus type 1): a phase 3, randomized, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1489–97. Phase 3 open label treat-to-target clinical trial data for insulin degludec done in patients with type 1 diabetes.

• Garber AJ, King AB, Del Prato S, Sreenan S, Balci MK, Munoz-Torres M, et al. Insulin degludec, an ultra-longacting basal insulin, vs insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomized, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1498–507. Phase 3 open label treat-to-target clinical trial data for insulin degludec done in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Bentley G, Dodson E, Dodson G, Hodgkin D, Mercola D. Structure of insulin in 4-zinc insulin. Nature. 1976;261:166–8.

Brader ML, Dunn MF. Insulin hexamers: new conformations and applications. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:341–5.

Derewenda U, Derewenda Z, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Reynolds CD, Smith GD, et al. Phenol stabilizes more helix in a new symmetrical zinc insulin hexamer. Nature. 1989;338:594–6.

Flora DB, Inventor. Fatty acid-acylated insulin analogs. U. S. A. patent 6,444,641. Sept 3, 2002.

Baker JC, Hanquier JM, Inventors. Acylated insulin analogs. U. S. A. patent 5,922,675. July 13, 1999.

Beals JM, DeFelippis MR, DiMarchi RD, Kohn WD, Micanovic R, Myers SR, et al., Inventors. Eli Lilly and Company, assignee. Insulin molecule having protracted time action. U.S.A. patent 2005/0014679. Jan 20, 2005.

Kohn WD, Zhang L, DiMarchi RD, Inventors. Insulin analogs having protracted time action. U. S. A. patent 2006/0217290. Sept 28, 2006.

•• Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hoeg-Jensen T, Steensgaard DB, Wahlund PO, Ribel U. Design of the novel protraction mechanism of insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin. Pharm Res. 2012;2104–2114. The mechanism of the long-acting insulin degludec analog is clearly laid out here along with much of the relevant biophysical data.

Phillips NB, Wan ZL, Whittaker L, Hu SQ, Huang K, Hua QX, et al. Supramolecular protein engineering: design of zinc-stapled insulin hexamers as a long acting depot. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11755–9.

• Sinha VP, Howey DC, Kwang D, Soon W, Choi SL, Mace KF, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics (PK) and glucodynamics (GD) of the novel, long-acting basal insulin LY2605541 in healthy subjects. In: Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association's 72nd Scientific Sessions. Philadelphia, PA: Eli Lilly and Co; 2012. Data that illustrates the extended effect of pegylated insulin lispro obtained in healthy human adults using a single dose.

Bergenstal RM, Rosenstock J, Arakaki RF, Prince MJ, Qu Y, Sinha VP, et al. Reduced nocturnal hypoglycemia and weight loss with novel, long-acting basal insulin LY2605541 compared with insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. In: Oral presentation at the American Diabetes Association's 72nd Scientific Sessions. Philadelphia, PA: Eli Lilly and Company; 2012.

•• Hansen RJ, Cutler JGB, Vick A, Koester A, Li S, Siesky AM, et al. LY2605541: Leveraging hydrodynamic size to develop a novel basal insulin 896-P. In: Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association's 72nd Scientific Sessions. Philadelphia, PA: Lilly Laboratories; 2012. Explains the rationale behind the design of pegylated insulin lispro and provides the supporting data done in rats.

Moore MC, Smith MS, Mace KF, Sinha VP, Dodson M, Jacober SJ,et al. Novel PEGylated basal Insulin LY2605541 has a preferential hepatic effect on glucose metabolism. In: Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association's 72nd Scientific Sessions. Philadelphia, PA: Department of Molecular Physiology & Biophysics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; 2012.

Webster R, Didier E, Harris P, Siegel N, Stadler J, Tilbury L, et al. PEGylated proteins: evaluation of their safety in the absence of definitive metabolism studies. Drug Metabol Dispos. 2007;35:9–16.

Davis FF. The origin of pegnology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:457–8.

Veronese FM, Pasut G. PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1451–8.

Bliss M. The discovery of insulin: twenty-fifth anniversary edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2007.

Whittaker J, Whittaker LJ, Roberts Jr CT, Phillips NB, Ismail-Beigi F, Lawrence MC, et al. α-Helical element at the hormone-binding surface of the insulin receptor functions as a signaling element to activate its tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11166–71.

Zib I, Raskin P. Novel insulin analogues and its mitogenic potential. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2006;8:611–20.

Nagel JM, Staffa J, Renner-Muller I, Horst D, Vogeser M, Langkamp M, et al. Insulin glargine and NPH insulin increase to a similar degree epithelial cell proliferation and aberrant crypt foci formation in colons of diabetic mice. Horm Canc. 2010;1:320–30.

Teng JA, Hou RL, Li DL, Yang RP, Qin J. Glargine promotes proliferation of breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7 via AKT activation. Horm Metab Res. 2011;43:519–23.

Lind M, Fahlen M, Eliasson B, Oden A. The relationship between the exposure time of insulin glargine and risk of breast and prostate cancer: an observational study of the time-dependent effects of antidiabetic treatments in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;6:53–59.

Blin P, Lassalle R, Dureau-Pournin C, Ambrosino B, Bernard MA, Abouelfath A, et al. Insulin glargine and risk of cancer: a cohort study in the French National Healthcare Insurance Database. Diabetologia. 2012;55:644–653.

Ruiter R, Visser LE, van Herk-Sukel MP, Coebergh JW, Haak HR, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, et al. Risk of cancer in patients on insulin glargine and other insulin analogues in comparison with those on human insulin: results from a large population-based follow-up study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:51–62.

Radermecker RP, Scheen AJ. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion with short-acting insulin analogues or human regular insulin: efficacy, safety, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness. Diabetes Metabol Res Rev. 2004;20:178–88.

Hirsch IB. Insulin analogues. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:174–83.

Leichter S. Is the use of insulin analogues cost-effective? Adv Ther. 2008;25:285–99.

Cameron CG, Bennett HA. Cost-effectiveness of insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus. CMAJ. 2009;180:400–7.

Osei K. Global epidemic of type 2 diabetes: implications for developing countries. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S102–6.

Osei K, Schuster DP, Amoah AG, Owusu SK. Pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa: implication for transitional populations. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2003;10:85–96.

Lefebvre P, Pierson A. The global challenge of diabetes. World Hosp Health Serv. 2004;40:37–40, 42.

Derewenda U, Derewenda Z, Dodson GG, Hubbard RE, Korber F. Molecular structure of insulin: the insulin monomer and its assembly. Br Med Bull. 1989;45:4–18.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and American Diabetes Association to one of the authors (M.A.W.). V.P. is a predoctoral fellow of the NIH Medical Scientist Training Program at the CWRU School of Medicine and is supported by NIH Fellowship F30DK094685-02.

Disclosure

Conflicts of Interest: The intellectual property pertaining to zinc-stapled human insulin analogs and its long-acting formulations are owned by Case Western Reserve University and licensed to Thermalin Diabetes, LLC. M.A. Weiss: holds shares in and is Chief Scientific Officer of Thermalin Diabetes, LLC.; he has also been a consultant to Merck, Inc. and the DEKA Research and Development Corp.; V. Pandyarajan: none. The authors otherwise declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pandyarajan, V., Weiss, M.A. Design of Non-Standard Insulin Analogs for the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diab Rep 12, 697–704 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-012-0318-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-012-0318-z