Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide for both men and women. However, CVD is understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in women. This bias has resulted in women being disproportionately affected by CVD when compared to men. The aim of this narrative review is to explore the contribution of sex and gender on CVD outcomes in men and women and offer recommendations for researchers and clinicians.

Recent Findings

Evidence demonstrates that there are sex differences (e.g., menopause and pregnancy complications) and gender differences (e.g., socialization of gender) that contribute to the inequality in risk, presentation, and treatment of CVD in women.

Summary

To start addressing the CVD issues that disproportionately impact women, it is essential that these sex and gender differences are addressed through educating health care professionals on gender bias; offering patient-centered care and programs tailored to women’s needs; and conducting inclusive health research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has historically been perceived as a male disease; however, it is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide for both men and women [1]. Despite this, CVD is understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in women [2]. Both sex — biological and anatomical factors — and gender — cultural and societal factors — have been found to be important modifiers of CVD but are often underappreciated in clinical practice. This leads to inequality in the outcomes and treatment of women with CVD. For example, mortality rates are improving at a faster rate in men compared to women [3]. Women also experience a greater delay in emergency response times [4], diagnosis, and revascularization compared to men [5, 6]. These delays are thought to be due to biological differences in the presentation of CVD in women and gender biases in both patients and health care professionals [7, 8]. There is growing recognition for the need to address issues with sex and gender in health research. However, much remains to be done [9,10,11,12].

The aim of this narrative review is to explore the complex sex and gender differences observed in the research, treatments, and outcomes of women with CVD. The review also includes recommendations for research and practice. For context, it is important to distinguish and define both sex and gender. Sex refers to the variation and expression of biological attributes such as genetics (e.g., sex chromosomes), sex hormones, anatomy, and physiology [13, 14]. In comparison, gender is a multidimensional construct that has been developed over time from social, cultural, and behavioral factors. Gender incorporates the dimensions identity, societal roles, interpersonal relationships, and institutionalized gender norms [13].

Examples of Sex-Specific Risk Factors of CVD

There are well established biological sex differences in the risk factors for CVD [15, 16]. Reviews of the literature demonstrate that sex-specific risk factors include age of first menarche, menopause, reproductive endocrine disorders, and pregnancy complications [17,18,19,20]. However, even shared risk factors such as diabetes and smoking have been found to impact CVD risk differently in women. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that the relative risk (RR) of CVD is 44% and 25% higher in women with diabetes and women who smoke when compared to men (RR ratio 1.44 (95% CI 1.27 to 1.63) and 1.25 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.39)) [21, 22], whereas blood pressure, body mass index, and hyperlipidaemia have been found to have a similar impact on CVD risk in men and women [22,23,24]. There are also differences in the presentation of CVD symptoms. While chest pain is the most commonly reported symptom in both men and women, women often have different or asymptomatic presentations compared to men [25]. Women regularly report additional symptoms such as epigastric symptoms, palpitations, and shortness of breath [25]. While understanding sex differences in CVD risk is important, it only provides part of the story. Just as there are differences in biological risk factors, there are differences in sociocultural risk factors between different genders [15, 26, 27].

Examples of Gender-Specific Risk Factors for CVD

Gender-specific risk factors include environmental factors that, for non-biological reasons, contribute to health disparities like exposure to violence, sociocultural behaviors and attitudes, and socioeconomic barriers [11, 28, 29]. A review article by O’Neil et al. [26] describes how gender acts as a social determinant of CVD. O’Neil et al. describe how the adoption of health behaviors is highly gendered. For example, the adoption of certain health behaviors such as being active and playing sports is encouraged in young men more so than in young women [30, 31]. There have been successful school-based intervention that have increased physical activity and reduced risk factors such as obesity in women [32]. These findings demonstrate that some of the gender-specific risk factors can be modified.

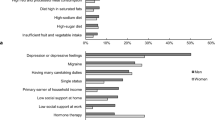

Another review conducted by Connelly et al. [13] describes how gender identity (e.g., personality traits and psychosocial stress), gender roles (e.g., carer responsibilities and primary earner status), and gender relations (e.g., marital status) increased CVD risk for women. Further, interpersonal relationships can also impact the risk of CVD. For instance, women who experience intimate partner violence and domestic abuse have an increased risk of CVD (incidence rate ratio 1.44 (95% CI, 1.24–1.6)) [33, 34]. In addition, women who live alone report greater barriers to care, such as greater financial issues in the recovery after acute coronary syndrome [35], which may impact their risk of a secondary event. Sexism has also been proposed as a psychosocial factor that influences the risk of CVD [36]. For example, the experience of sexism has been related to increased alcohol consumption and smoking in women [37], behaviors that increase the risk of CVD.

Gender biases in medical professionals also contribute to the differences in outcomes for CVD between women and men. An example of this gender bias across health outcomes is demonstrated when examining the association between patient-physician gender concordance and patient outcomes. Women have a higher mortality rate and worse outcomes when treated by male doctors [8]. While this may also be due to bias in reporting by women, these outcomes are improved when women have a female doctor or if their male doctor works with women and has treated more women in the past [8]. These biases are also present in the primary health care setting, women are less likely than men to have their CVD risk [38] and smoking status assessed [39]. After treatment for a cardiac event, there are gender biases that impact who bears the burden of care during recovery; in general, women tend to take on caregiving roles within families [40]. This bias may affect to whom information about care and recovery is directed to, for example, in heterosexual couples, the responsibility of care may be placed on the woman. In the care of cancer patients, this burden of care results in women reporting worse mental health outcomes [41, 42]. There is also bias in referral to secondary prevention programs. A meta-analysis conducted in 2015 found that men were 1.5 times more likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation (CR) than women (odds ratio 0.68 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.74)) [43]. Once referred to CR, women are also less likely to attend [44, 45•]. This is due to several barriers, including carer responsibilities, work commitments, geographical barriers, and perceptions about program characteristics [46].

Examples of Intersecting Sex and Gendered Risk Factors for CVD

It is difficult to disentangle sex and gender influences on the differences in diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for women with CVD. This is because both gender and sex interact to contribute to this discrepancy (Fig. 1). For example, psychosocial and biological factors increase the risk of mental health issues which in turn have been found to increase the risk of CVD [47]. Overall, these mental health issues disproportionately affect women more than men [48] and have been found to be an independent risk factor for CVD in women [49]. The diagnosis of depression has also been associated with worse outcomes, including morbidity and mortality for people with CVD [50, 51].

Sex and gender also interact to impact how accurately women interpret their CVD risk [5], resulting in men being more likely to interpret their symptoms as cardio specific during myocardial infarction (51.7 vs. 46.0%; p = 0.02) [52]. This misinterpretation of symptoms has been found to result in a 2-h delay in seeking treatment [52]. Qualitative research has also demonstrated how sex and gender interact to impact the delay in treatment for women, the interpretation of risk in combination with symptom presentation, and past responses from health professionals impact the time women take to seek treatment during their first cardiovascular event [53]. On average, women with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have a 30-min longer ischemic time when compared to men after controlling for confounders [5]. After further investigation, there are delays in both symptoms to door time (time taken from the presentation of symptoms to arrival at hospital) and door to balloon time (time from arrival to revascularization) for women [5].

These delays seem to be caused by multiple factors, highlighting complex interactions between sex and gender. As established, women take longer to seek medical treatment (on average 3.2 h for women versus 2.4 for men) [25]. There are also delays in the time it takes for women to arrive at the hospital. In Norway, women with STEMI were given lower priority for ambulance services than men with similar presentations and took longer to arrive at the hospital [4]. Once women arrive at the hospital, there is also a delay in receiving the correct diagnosis and intervention [54]. These delays in receiving life-saving care are associated with a higher mortality rate in women [5]. An Australian study found similar results with women being 18% less likely to receive an urgent care allocation upon admission to the emergency department (OR 0.82 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.85)), 16% less likely to be seen by an emergency physician in the first hour of arrival at emergency (mean difference 0.15 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.1)), 20% less likely to have a diagnostic troponin test (OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.83)), 36% less likely to be admitted to a special care unit (OR 0.64 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.68)), and finally, women were also found to be more likely to die during their hospital admission [55••].

Recommendations for Researchers

Historically, women have been underrepresented in health research, including CVD research [2, 9, 56]. This underrepresentation of women in research partially explains the incomplete understanding of CVD symptomology and presentation in women. For example, the 2016 National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand clinical guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes was based on research that had inequality in sex and gender representation [57]. Scovellsce et al. (2020) examined the studies used to inform the guidelines and found that beyond mere participation of women in research, only 70% of studies mention either sex or gender in the body of the publication; 78% of studies included reported on the number of men and women in the study cohort; only 50% and 18% of studies reported on sex or gender disaggregated results respectively in the exposure and primary outcome; and only 23% included sex or gender in the statistical model. These findings highlight the gender bias in evidence underpinning current CVD guidelines and the need for policies to ensure that women are equally represented in all health research, including CVD.

While progress has been made to ensure the inclusion of women in research and the consideration of sex in the analysis of health outcomes, there is still need to consider gender in the analysis and interpretation of health outcomes [19, 58•]. Table 1 describes some of the recommendations for how researchers can do this.

Recommendations and Clinicians

Based on the persistent sex and gender differences in the risk, diagnosis, and treatment of CVD, several steps must be taken to ensure no group of people are disproportionately affected by CVD. A recent scoping review demonstrated that there are 13 published studies that evaluate interventions aimed at reducing the gender disparity CVD outcomes in health care [77]. This highlights the need for additional evidence-based interventions to address the sex and gender bias in health care. Table 2 describes some of the ways clinician can address these issues.

Conclusions

There are sex and gender differences in the risk, presentation, treatment, and research of CVD. These differences have resulted in women being disproportionally affected by CVD. While some differences are due to biological differences between males and females, many can be attributed to biases in both patients, health professionals, and societal norms. Further, sex and gender appear to interact to contribute to the differences in risk and outcomes for women. In order to reduce the inequity in health outcomes for women, these biases must be addressed through improving the communication of biological differences in the presentation of CVD; educating health care professionals on gender bias; offering patient-centered care and programs tailored to women’s needs; and conducting research that includes sex and gender-based analysis. By conducting more inclusive research and addressing the gender biases present in health care, we may start addressing the CVD issues that disproportionately impact half of the world’s population.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

World Health Organization. (2021). Cardiovascular diseases (CVD). 2021. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1. Accessed 24 Aug 2021.

Burgess SN. Understudied, under-recognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated: sex-based disparities in cardiovascular medicine. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022; 15(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1161/circinterventions.121.011714.

Bots SH, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality: a global assessment of the effect of ageing between 1980 and 2010. BMJ Glob Heal. 2017;2(2):1–8.

Melberg T, Kindervaag B, Rosland J. Gender-specific ambulance priority and delays to primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a consequence of the patients’ presentation or the management at the emergency medical communications center? Am Heart J [Internet]. 2013;166(5):839–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.034.

Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A, Dinh DT, Lefkovits J, Zaman S. Sex differences persist in time to presentation, revascularization, and mortality in myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(10):1–9.

Khan E, Brieger D, Amerena J, Atherton JJ, Chew DP, Farshid A, et al. Differences in management and outcomes for men and women with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Med J Aust. 2018;209(3):118–23.

Bairey Merz CN, Andersen H, Sprague E, Burns A, Keida M, Walsh MN, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding cardiovascular disease in women: the Women’s Heart Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):123–32.

Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(34):8569–74.

Nowatzki N, Grant KR. Sex is not enough: the need for gender-based analysis in health research. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32(4):263–77.

Phillips SP. Including gender in public health research. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(SUPPL. 3):16–21.

Nielsen MW, Stefanick ML, Peragine D, Neilands TB, Ioannidis JPA, Pilote L, et al. Gender-related variables for health research. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12(1):1–16.

Day S, Mason R, Lagosky S, Rochon PA. Integrating and evaluating sex and gender in health research. Heal Res Policy Syst [Internet]. 2016;14(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0147-7.

Connelly PJ, Azizi Z, Alipour P, Delles C, Pilote L, Raparelli V. The importance of gender to understand sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2021;37(5):699–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.02.005.

Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:1–11.

Seeland U, Nemcsik J, Lønnebakken MT, Kublickiene K, Schluchter H, Park C, et al. Sex and gender aspects in vascular ageing—focus on epidemiology, pathophysiology, and outcomes. Hear Lung Circ [Internet]. 2021;30(11):1637–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2021.07.006.

Mehta PK, Wei J, Wenger NK. Ischemic heart disease in women: a focus on risk factors. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(2):140–51.

Gao Z, Chen Z, Sun A, Deng X. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease. Med Nov Technol Devices [Internet]. 2019;4(October):100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medntd.2019.100025.

Luijken J, van der Schouw YT, Mensink D, Onland-Moret NC. Association between age at menarche and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review on risk and potential mechanisms. Maturitas [Internet]. 2017;104:96–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.07.009.

Norris CM, Yip CYY, Nerenberg KA, Clavel MA, Pacheco C, Foulds HJA, et al. State of the science in women’s cardiovascular disease: a Canadian perspective on the influence of sex and gender. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(4):1–9.

Barrett-Connor E. Menopause, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2013;13(2):186–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2013.01.005.

Peters SAE, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1542–51.

Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet [Internet]. 2011;378(9799):1297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60781-2.

Mongraw-Chaffom M, Peters SAE, Huxley RR, Woodward M. The sex-specific relationship between body mass index and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95 cohorts with 1.2 million participants. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(6):437–49.

Peters SAE, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Comparison of the sex-specific associations between systolic blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 124 cohort studies, including 1.2 million individuals. Stroke. 2013;44(9):2394–401.

Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, Bao H, Krumholz HM, Lorenze NP, et al. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2018;137(8):781–90.

O’Neil A, Scovelle AJ, Milner AJ, Kavanagh A. Gender/sex as a social determinant of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2018;137(8):854–64.

Möller-Leimkühler AM. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease and comorbid depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(1):71–83.

Wenger NK. Gender disparity in cardiovascular disease: bias or biology? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10(11):1401–11.

Spagnolo PA, Manson JAE, Joffe H. Sex and gender differences in health: what the COVID-19 pandemic can teach us. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):385–6.

Lau PWC, Lee A, Ransdell L. Parenting style and cultural influences on overweight children’s attraction to physical activity. Obesity. 2007;15(9):2293–302.

Lampinen EK, Eloranta AM, Haapala EA, Lindi V, Väistö J, Lintu N, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and socioeconomic status among Finnish girls and boys aged 6–8 years. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(4):462–72.

Kaestner R, Xu X. Title IX, girls’ sports participation, and adult female physical activity and weight. Eval Rev. 2010;34(1):52–78.

El-Serag R, Thurston RC. Matters of the heart and mind: interpersonal violence and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(4):1–4.

Chandan JS, Thomas T, Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, Bandyopadhyay S, Nirantharakumar K. Risk of cardiometabolic disease and all-cause mortality in female survivors of domestic abuse. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(4):1–8.

Gallagher R, Marshall AP, Fisher MJ, Elliott D. On my own: experiences of recovery from acute coronary syndrome for women living alone. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2008;37(6):417–24.

Molix L. Sex differences in cardiovascular health: does sexism influence women’s health? Am J Med Sci. 2014;348(2):153–5.

Zucker AN, Landry LJ. Embodied discrimination: the relation of sexism and distress to women’s drinking and smoking behaviors. Sex Roles. 2007;56(3–4):193–203.

Hyun KK, Redfern J, Patel A, Peiris D, Brieger D, Sullivan D, et al. Gender inequalities in cardiovascular risk factor assessment and management in primary healthcare. Heart. 2017;103(7):500–6.

Hyun KK, Millett ERC, Redfern J, Brieger D, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in primary health care: a systematic review. Hear Lung Circ [Internet]. 2019;28(10):1535–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.04.005.

Folbre N. The care penalty and gender inequality. In: The Oxford handbook of women and the economy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. pp. 749–66.

Ketcher D, Trettevik R, Vadaparampil ST, Heyman RE, Ellington L, Reblin M. Caring for a spouse with advanced cancer: similarities and differences for male and female caregivers. J Behav Med [Internet]. 2020;43(5):817–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00128-y.

Kuenzler A, Hodgkinson K, Zindel A, Bargetzi M, Znoj HJ. Who cares, who bears, who benefits? Female spouses vicariously carry the burden after cancer diagnosis. Psychol Heal. 2011;26(3):337–52.

Colella TJ, Gravely S, Marzolini S, Grace SL, Francis JA, Oh P, et al. Sex bias in referral of women to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation? A meta-analysis Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(4):423–41.

Samayoa L, Grace SL, Gravely S, Scott LB, Marzolini S, Colella TJF. Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2014;30(7):793–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2013.11.007.

• Hyun K, Negrone A, Redfern J, Atkins E, Chow C, Kilian J, et al. Gender difference in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and outcomes following the survival of acute coronary syndrome. Hear Lung Circ [Internet]. 2021;30(1):121–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2020.06.026. (This prospective study found that women attended cardiac rehabilitation less often and had a higher risk of a secondary cardiovascular event 6 months later when compared to men.)

Resurrección DM, Motrico E, Rigabert A, Rubio-Valera M, Conejo-Cerón S, Pastor L, et al. Barriers for nonparticipation and dropout of women in cardiac rehabilitation programs: a systematic review. J Womens Health. 2017;26:849–59.

Silverman AL, Herzog AA, Silverman DI. Hearts and minds: stress, anxiety, and depression: unsung risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev. 2019;27(4):202–7.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Mental health [Internet]. 2018. p. 1500–31. Available from:. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/mental-health/latest-release#key-statistics. Accessed 29 Nov 2021.

O’Neil A, Fisher AJ, Kibbey KJ, Jacka FN, Kotowicz MA, Williams LJ, et al. Depression is a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women: an 18-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 2016;196:117–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.029.

Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression, mortality, and medical morbidity in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):241–7.

Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(12):1350–69.

Kirchberger I, Heier M, Wende R, Von Scheidt W, Meisinger C. The patient’s interpretation of myocardial infarction symptoms and its role in the decision process to seek treatment: the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101(11):909–16.

Gallagher R, Marshall AP, Fisher MJ. Symptoms and treatment-seeking responses in women experiencing acute coronary syndrome for the first time. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care [Internet]. 2010;39(6):477–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.019.

Lawesson SS, Isaksson RM, Ericsson M, Ängerud K, Thylén I. Gender disparities in first medical contact and delay in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective multicentre Swedish survey study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):1–10.

•• Mnatzaganian G, Hiller JE, Braitberg G, Kingsley M, Putland M, Bish M, et al. Sex disparities in the assessment and outcomes of chest pain presentations in emergency departments. Heart. 2020;106(2):111–8. (Findings from this study demonstrate the sex differences in the treatment and outcomes between men and women after presenting to emergency with chest pain.)

Scovelle AJ, Milner A, Beauchamp A, Byrnes J, Norton R, Woodward M, et al. The importance of considering sex and gender in cardiovascular research. Hear Lung Circ [Internet]. 2020;29(1):e7-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.08.011.

Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, French JK, Briffa TG, Tideman PA, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2016. Hear Lung Circ. 2016;25(9):895–951.

• Wainer Z, Carcel C, Hickey M, Schiebinger L, Schmiede A, McKenzie B, et al. Sex and gender in health research: updating policy to reflect evidence. Med J Aust. 2020;212(2):57-62.e1. (This paper provides recommendations for policies and practices to reduce the sex and gender differences observed in health research in Australia.)

White J, Tannenbaum C, Klinge I, Schiebinger L, Clayton J. The integration of sex and gender considerations into biomedical research: lessons from international funding agencies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(10):3034–48.

PhenX Toolkit [Internet]. Protocol—gender identity. 2022. Available from: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/11801?origin=subcollection. Accessed 26 April 2022.

Petit G, Tedds LM. Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) of the current system of income and social supports in British Columbia. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3781918.

Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L. A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(5):517–26.

Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, Daskalopoulou SS, Eisenberg MJ, Bacon SL, et al. Sex versus gender-related characteristics which predicts outcome after acute coronary syndrome in the young? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):127–35.

Hammarström A, Johansson K, Annandale E, Ahlgren C, Aléx L, Christianson M, et al. Central gender theoretical concepts in health research: the state of the art. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(2):185–90.

Cochrane Equity Methods Group. Cochrane methods equity [Internet]. PROGRESS-Plus. [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/projects/evidence-equity/progress-plus#:~:text=PROGRESS-Plusis.

Caceres BA, Jackman KB, Edmondson D, Bockting WO. Assessing gender identity differences in cardiovascular disease in US adults: an analysis of data from the 2014–2017 BRFSS. J Behav Med [Internet]. 2020;43(2):329–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00102-8.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables. 2020. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standard-sex-gender-variations-sex-characteristics-and-sexual-orientation-variables/latest-release. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Tannenbaum C, Ellis RP, Eyssel F, Zou J, Schiebinger L. Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature [Internet]. 2019;575(7781):137–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1657-6.

Nieuwenhove L, Bertens M, Klinge I. Gender awakening tool [Internet]. 2007. Available from: http://www.genderbasic.nl/downloads/pdf/WISERfestbookletextrapages.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2022.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables. 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standard-sex-gender-variations-sex-characteristics-and-sexualorientation-variables/latest-release. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

Doull M, Runnels V, Tudiver S, Boscoe M. Sex and gender in systematic reviews planning tool. The Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group [Internet]. 2011;1–2. Available from:. http://methods.cochrane.org/sites/methods.cochrane.org.equity/files/public/uploads/SRTool_PlanningVersionSHORTFINAL.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2022.

European Commission. Toolkit gender in EU-funded research [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c17a4eba-49ab-40f1-bb7b-bb6faaf8dec8.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Canadian Institutes of Health Research [Internet]. Sex and gender in health research. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50833.html.

National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health [Internet]. NIH policy on sex as a biological variable. [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender/nih-policy-sex-biological-variable.

National Instisututes of Health. National Institutes of Health [Internet]. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. [cited 2022 Mar 14]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm#:~:text=Itisthepolicyofthatinclusionisinappropriatewith.

Woodward M. Rationale and tutorial for analysing and reporting sex differences in cardiovascular associations. Heart. 2019;105:1701–8.

Alcalde-Rubio L, Hernández-Aguado I, Parker LA, Bueno-Vergara E, Chilet-Rosell E. Gender disparities in clinical practice: are there any solutions? Scoping review of interventions to overcome or reduce gender bias in clinical practice. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–8.

Huded CP, Johnson M, Kravitz K, Menon V, Abdallah M, Gullett TC, et al. 4-Step protocol for disparities in STEMI care and outcomes in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2122–32.

Glickman SW, Granger CB, Ou FS, O’Brien S, Lytle BL, Cairns CB, et al. Impact of a statewide ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction regionalization program on treatment times for women, minorities, and the elderly. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):514–21.

Gagliardi AR, Dunn S, Foster A, Grace SL, Green CR, Khanlou N, et al. How is patient-centred care addressed in women’s health? A theoretical rapid review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):1–9.

Low TT, Chan SP, Wai SH, Ang Z, Kyu K, Lee KY, et al. The women’s heart health programme: a pilot trial of sex-specific cardiovascular management. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Mamataz T, Ghisi GLM, Pakosh M, Grace SL. Nature, availability, and utilization of women-focused cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord [Internet]. 2021;21(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02267-0.

Murphy BM, Zaman S, Tucker K, Alvarenga M, Morrison-Jack J, Higgins R, et al. Enhancing the appeal of cardiac rehabilitation for women: development and pilot testing of a women-only yoga cardiac rehabilitation programme. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20(7):633–40.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. SG is funded by a NHMRC Synergy Grant (APP1182301). SC is funded by a Heart Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (#104860). JR is funded by a NHMRC investigator Grant (GNT2007946).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women and Ischemic Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gauci, S., Cartledge, S., Redfern, J. et al. Biology, Bias, or Both? The Contribution of Sex and Gender to the Disparity in Cardiovascular Outcomes Between Women and Men. Curr Atheroscler Rep 24, 701–708 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01046-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01046-2