Abstract

Understanding the dynamics of stability and change is key to accelerate sustainability transitions. This paper aims to advance and inspire sustainability transition research on this matter by collecting insights from interpretative environmental discourse literature. We develop a heuristic that identifies and describes core discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system. In doing so, we show how the interplay of meta-, institutionalized, and alternative discourses, dominant, marginal, and radical narratives, as well as weak and strong discursive agency influence the socio-technical configuration. The heuristic suggests three discursive lock-ins reinforcing the stabilization of socio-technical systems: unchallenged values and assumptions, incumbents’ discursive agency, and narrative co-optation. Furthermore, it explores three pathways of discursive change: disruptive, dynamic and cross-sectoral. Overall, this paper puts forward a discursive perspective on sustainability transitions. It offers additional analytical approaches and concepts for discursive transition studies, elaborated insights on the dynamics within and between the analytical dimensions of a socio-technical system, as well as a theoretical baseline for analyzing discursive lock-in mechanisms and pathways of discursive change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The exchange between various social science disciplines is crucial to enhance the understanding and analysis of transformations toward sustainability. This paper contributes to this exchange. It connects key concepts of sustainability transition studies and environmental discourse literature, offering a discursive perspective on sustainability transitions. The scientific field of sustainability transitions analyzes structural and systemic changes toward sustainability; it explores such changes in production and consumption patterns as well as their related societal challenges. This academic community holds the underlying assumption and motivation that solutions to the environmental problems brought by unsustainable production and consumption “cannot be addressed by incremental improvements and technological fixes, but require radical shifts to new kinds of socio-technical systems” (Köhler et al. 2019, p. 2). Socio-technical systems (such as energy, water, or mobility) are commonly understood to represent the interactions and interlinkages between actors and their established practices, institutions, and material artifacts fulfilling a societal function (Fuenfschilling and Truffer 2016). To achieve a sustainable society, various socio-technical systems require fundamental shifts. This means that “sustainability transitions are long-term, multi-dimensional, and fundamental transformation processes through which established socio-technical systems shift more toward sustainable modes of production and consumption” (Markard et al. 2012, p. 956). Sustainability transitions research focuses primarily on processes of stability and change to find ways that support the acceleration and governance of these transitions.

To address these complex questions, the field of sustainability transitions has broadened its horizons in various directions (Köhler et al. 2019). The academic community is continuously growing and expanding the topics, geographies, and methods covered in the field. On a theoretical level, transition scholars are exploring new alleys of exchange with other social science theories and disciplines (e.g.,Geels 2010; Geels et al. 2016; Sovacool and Hess 2017). The field of interpretative, constructivist, and poststructuralist approaches has been identified as promising to further develop the understanding and analysis of processes of stability and change for sustainability (Geels 2010; Geels and Verhees 2011; Köhler et al. 2019; Sovacool and Hess 2017). These approaches point to the relevance of values, assumptions, and discourses expressed through language in shaping transition processes. Consequently, using an interpretative lens for the analysis of these discourses is crucial to understand how sustainable futures are created, as well as how these discourses undermine or support existing unsustainable structures and practices (Feola and Jaworska 2019).

The adoption of interpretative research designs, such as discourse analysis, in transition research has increased significantly over the last decade (Isoaho and Karhunmaa 2019). This has led to multiple new insights on sustainability transition that were not possible without this ontological shift. First, using discourse analysis has led to a more politically sensitive understanding of transition processes: seen for example by the analyses of actors’ visions, narratives, and coalitions (Kern 2011), the power of incumbents (Bosman et al. 2014; Geels 2014), and the role of framing and interpretation (Hermwille 2016; Kriechbaum et al. 2021). Second, integrating discursive concepts into transition research has enhanced the understanding of the production of cultural legitimacy for alternative ideas (Geels and Verhees 2011; Rosenbloom 2018) as well as the role of negative narratives for undermining the dominant socio-technical configuration (Roberts 2017). Overall, the use of interpretative discourse analysis in transition studies has mainly focused on specific cases of sense-making and how this sense-making legitimizes or delegitimizes certain sustainability transition pathways. A more structured exchange is lacking between transition research and interpretative discourse analysis (in the field of environmental policy) on the role of discursive elements in processes of stability and change. This limits the understanding of the discursive mechanisms hindering sustainability transitions and the potential pathways enabling discursive change.

To facilitate this exchange between social science disciplines and to enhance the discursive perspective on sustainability transitions, this paper presents a heuristic that links key concepts of environmental discourse literature and transition research. First, we identify and describe core discursive elements relevant for understanding processes of stability and change in the interpretative discourse literature (“Interpretative discourse analysis on processes of stability and change”). Second, we link these core discursive elements to the prominent analytical dimensions of transition research (landscape, regime, and niche) to show how these discursive elements and their dynamics influence the configuration of a socio-technical system (“Discursive dynamics in a socio-technical system”). Third, we explore the role of these discursive elements and dynamics on persistent stability by conceptualizing various discursive lock-in mechanisms and outlining potential pathways of discursive change (“A conceptualization of discursive lock-in mechanisms”). Building on the insights generated with this heuristic, we discuss the added value of this discursive perspective for future transition research and governance (“Discussion and conclusions”). In sum, this study (1) offers additional analytical approaches and concepts for discursive transition studies; (2) elaborates the understanding of the dynamics within and between the various analytical dimensions of a socio-technical system; and (3) provides an ideal–typical conceptualization of discursive lock-in mechanisms and pathways of discursive change, supporting a discursive perspective on socio-technical systems—next to the material, institutional and behavioral counterparts.

Interpretative discourse analysis on processes of stability and change

Interpretative discourse approaches have their origin in critical and interpretative policy studies, which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s as a critique of the positivistic and rational conception of knowledge and its consequent analysis of political processes (Fischer and Forester 1993). The dominant technocratic policy research failed to find helpful solutions to the social and political problems of the time, whereas interpretative approaches brought in a new understanding of these problems by including the historical and cultural dimensions of knowledge creation and decision-making (Fischer et al. 2015). Based on the idea that knowledge is something “constructed” rather than “objective”, a new perspective on reality arose, as something individual rather than general (Berger and Luckmann 1966). This new perspective not only led to different political discussions, it initiated a reflection on the (social) sciences themselves (Münch 2015). Building on the work of philosopher Michel Foucault, various discursive approaches and heuristics have been developed, such as Laclau and Mouffe’s post-Marxist Discourse Theory, the Critical Discourse Analysis of Fairclough, the Argumentative Discourse Analysis of Hajer, Schmidt’s Discursive Institutionalism, Keller’s Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse, and the Discursive Agency Approach of Leipold and Winkel. While these approaches differ in their specific focus and objective, they share an aim to understand and analyze the role of socially constructed structures, expressed through language, in shaping actions. Increasingly, multiple social science disciplines are employing discursive concepts, theories, and methods to understand processes of (environmental) politics and policy change (Keller 2012; Leipold et al. 2019). Although various authors have reviewed and summarized the interpretative discourse literature (e.g.,Fischer et al. 2015; Leipold and Winkel 2017; Scrase and Ockwell 2010), we deem it necessary for this paper’s conceptual baseline to explore the key discursive elements and their contribution to a discursive understanding of stability and change.

Institutionalized and alternative discourses

The interpretative discourse literature holds various definitions and descriptions of the concept “discourse”. For example, Dryzek (2013) describes discourse as “a shared way of apprehending the world. Embedded in language it enables subscribers to interpret bits of information and put them together into coherent stories or accounts. Each discourse rests on assumptions, judgements, and contentions that provide the basic terms for analysis, debates, agreements and disagreements” (p.8). Alternatively, Hajer and Versteeg (2005) define discourse a little more specifically, as “an ensemble of ideas, concepts and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced through an identifiable set of practices” (p.1). Overall, any discussion can be perceived as an exemplification of competing discourses struggling for dominance, as the dominant discourse’s interpretation of the issue will be perceived as common sense and hold power over the problem description, appropriate solutions, and responsibilities (Carstensen and Schmidt 2016; Leipold and Winkel 2017).

Over time, a discourse can become sanctioned (Williams 2020) or institutionalized (Hajer 1995), meaning that its assumptions are unquestioned and its meaning structures are reflected in the material reality, institutional configuration, and social practices. This dominance is not permanent; it may be challenged by alternative discourses transferring a different meaning structure. This discursive struggle is an ongoing process and forms the arena for dynamics of stability and change. Important is that both institutionalized and alternative discourses “require a constant discursive reproduction [through narratives and discursive agents] to guarantee the continuity of its meaning structures” (Hajer 1995, p. 125). Discursive change is when an alternative meaning structure with its other materialities, institutions, and practices is reproduced more than the institutionalized one.

Dominant, marginal, and radical narratives

Narratives (also called storylines) form a key element of the discursive struggle between institutionalized and alternative discourses. Hajer (1995, 2006) explores the concept in depth in his Argumentative Discourse Analysis and this understanding was taken up by other approaches such as Discursive Institutionalism, Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse, and the Discursive Agency Approach. Narratives here are often conceptualized as a subset of overarching discourses. They summarize discourses in condensed stories, containing heroes and villains struggling in a specific setting, a plot outlining their motives, and a morality suggesting specific advice (e.g., a policy solution). In doing so, narratives make complex issues and debates tangible and allow actors to transfer meaning structures. When a majority of the actors involved reproduce the same narrative, it can be perceived as dominant and will shape an unchallenged understanding of the given issue and its appropriate actions, contributing to the institutionalization of the overall discourse. For a narrative to become dominant it needs to be attractive, convincing, and legitimate. The interpretative discourse literature identifies various factors that may enhance these characteristics, such as sufficient ambiguity (Hajer 1995; Stone 1989), a relation to historical or current events (Stone 1989), easy and emotion-evoking language (Leipold and Winkel 2016; Stone 1989), as well as appealing symbols and metaphors (Hajer 1995) or frames (Keller 2011).

In response to the institutionalized discourse and its dominant narratives, alternative narratives may emerge and evolve, which form the “prime vehicles of change” (Hajer 1995, p. 63). These alternative narratives can vary regarding their orientation toward the dominant discourse, presenting stories that differ only “marginally” to ones that differ “radically” (Hajer 1995, p. 232). The success of these marginal or radical narratives largely depends on the legitimacy and reproduction of the alternative viewpoints in question. Consequently, there occurs a “discursive dilemma” (Hajer 1995, p. 57). A radical narrative presenting a completely new story risks not being reproduced at all, whereas a marginally different narrative aligning with the dominant ideas risks inducing only incremental change.

Strong and weak discursive agency

Another key element of the discursive struggle is discursive agency, which received specific attention in the interpretative discourse literature with the introduction of the Discursive Agency Approach. Following Leipold and Winkel (2017), discursive agency “can be defined as an actor’s ability to make him/herself a relevant agent in a particular discourse by constantly making choices about whether, where, when, and how to identify with a particular subject position in specific storylines [narratives] within this discourse” (p. 524). This ability to become a strong discursive agent largely depends on the positional characteristics (e.g. mandates, resources, etc.) and individual characteristics (e.g. skills, knowledge, etc.) attributed to the actor. Next to that, Leipold and Winkel (2017) point to a wide range of strategic practices that discursive agents can use to support their narratives, such as coalition building (derived from Hajer 1995), discursive practices such as rationalizing or emotionalizing the debate, excluding or delegitimizing some actors and their narratives, as well as governance and organizational strategic practices that target the discussion format itself.) Leipold (2021) presents a concise overview and an empirical example of the various strategic practices identified in the interpretative discourse literature so far. In sum, the reproduction of narratives not only depends on the narrative itself, but also on the characteristics and strategic practices of the actors and coalitions that actively transfer its meaning constructs.

Meta-discourse

Finally, many discourse scholars point to deep-rooted values and assumptions or meta-discourses as being relevant to the discursive struggle. These meta-discourses are not specific to one political issue or actor, but rather, are more abstract and general. Fairclough (2012) sees these meta-discourses in “recent and contemporary processes of social transformation which are variously identified by such terms as ‘neo-liberalism’, ‘globalization’, ‘transition’” (p.452). These meta-discourses can also be understood as an “order of discourse”, a concept introduced by Foucault (1972), referring to overarching dominant constructs of meaning in society. This is not to say there are no alternative meaning structures, but once a particular meta-discourse becomes dominant it appears to be common sense and thereby sustaining itself (Sengul 2019). In other words, meta-discourses are strong and fixed abstract ideas that set an even broader context in which the interactive processes between discourses, narratives, and agents takes place. This means that changes in the ideological context are needed to radically change the outcome of the discursive struggle: “changes in semiosis [meta-discourse] are a precondition for wider processes of social change” (Fairclough 2012, p. 458). Nevertheless, the meta-discourse is often “‘outside’ or ‘beyond’ politics” and becomes unquestionable (Machin 2019, p. 209). Therefore, analyzing the deeper assumptions behind a discourse is crucial to understand its structural context and how these assumptions are reproduced (cf. Inayatullah 1998, on causal layered analysis). Making these structures visible through deconstruction is a first step toward analyzing and critically discussing the power of these ideas, consequently enabling change (Fairclough 2012).

Discursive dynamics in a socio-technical system

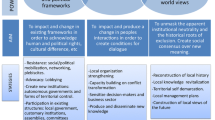

To address the second objective of this paper and conceptualize the discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system, we relate the various discursive elements (as discussed in “Interpretative discourse analysis on processes of stability and change”) to the prominently used analytical dimensions in transition studies, i.e., landscape, regime, and niche, which represent a continuum of degrees of structuration in and beyond a socio-technical system. Following Fuenfschilling and Truffer (2014), we understand these dimensions as an analytical perspective to differentiate between degrees of structuration and to disentangle the complexity of dynamics in a socio-technical system. In our conceptualization, we add a discursive perspective to the analytical dimensions, showing what discursive elements and dynamics are at play, and illuminating their role in the configuration of the socio-technical system. We address each of the analytical dimensions and the related discursive elements and dynamics in more detail in the subsections of this chapter as well as graphically in Fig. 1. With this conceptualization, we aim to provide a heuristic to guide scientific inquiry on discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system rather than enforce a rigid framework. As both discursive and socio-technical developments are dependent on interpretations and their context-specific developments, other discursive dynamics may be found in each empirical case. While not exhaustive, this heuristic provides a conceptual foundation and a starting point to analyze socio-technical systems from a discursive perspective.

Discursive elements, dynamics and lock-ins in a socio-technical system. The various discursive elements (meta-, institutionalized, and alternative discourse, dominant, marginal and radical narratives, as well as strong and weak discursive agency) and the commonly used analytical dimensions of transition studies (landscape, regime, and niche) can both be placed on a continuum of structuration, from well-developed structuration to structuration in development. This figure shows which discursive elements align with which dimensions and illuminates the discursive dynamics that influence the established practices, institutions, and material artifacts of the socio-technical system. Key discursive dynamics are the contextual power of the meta-discourse, the discursive struggle between institutionalized and alternative discourses as well as the continuous strive for reproduction and legitimacy of all types of narratives and discursive agents. Three main discursive lock-in mechanisms support the persistent stability of a socio-technical system as they self-reinforce the reproduction of the institutionalized discourse: the unchallenged values of the meta-discourse, the incumbents’ strong discursive agency, as well as the potential narrative co-optation that reinforce existing structures. These lock-in mechanisms reinforce the status quo and need to be unlocked to achieve a sustainability transition

Meta-discourses at the landscape dimension

In transition research, the landscape dimension forms one end of the continuum of structuration, representing overarching societal values, trends, and events (e.g. globalization or natural disasters) that shape the external context of a socio-technical system (Geels 2004; Schot and Kanger 2018). Applying a discursive perspective, meta-discourses characterize the landscape dimension, building on values and assumptions that are unchallenged and often perceived as common sense in more than one system. In this view, meta-discourses shape the external context and directionality of the emergence and development of socio-technical systems (represented as an overarching box in Fig. 1). Consequently, the relation of the meta-discourse with other discursive elements at the regime and niche dimensions forms a key discursive dynamic. Meta-discourses are not sector or actor specific and may be shared by various socio-technical systems. For instance, discussions on environmental policy in various domains are often shaped by the meta-discourse “ecological modernization” (e.g.,Bäckstrand and Lövbrand 2006; Dryzek 2013; Hajer 1995). This ideological construct is structured around the idea that economic growth and environmental protection can go hand-in-hand; it “refers to a restructuring of the capitalist political economy along more environmentally sound lines” (Hajer 1995, p. 25). In this way, it allows for a new orientation toward more environmentally friendly practices without challenging the overarching capitalist ideas and assumptions (Dryzek 2013). Learning from the interpretative discourse literature, it is key to critically reflect on these underlying values and assumptions (Fairclough 2012), to foster active societal discussions (Inayatullah 1998), and to make the meta-discourse part of the discursive struggle (Leipold 2021; Machin 2019).

Institutionalized discourses at the regime dimension

The regime dimension, holding institutionalized rules and practices of a specific socio-technical system (e.g., energy, water, or mobility), represents the middle part of the continuum of structuration (Fuenfschilling and Truffer 2014; Geels 2004). In our ideal–typical conceptualization, we relate the regime to an institutionalized discourse represented by dominant narratives and strong discursive agency. Following this discursive perspective, we argue that the institutionalized discourse shapes the development and structuration of the other system elements, such as established practices (e.g., patterns of production and consumption), institutions (e.g., regulations, standards, values), and a range of material artifacts such as technologies and infrastructure (see Fig. 1). Of course, in an empirical transition context, a dialectic or co-evolutionary relationship between discourses and other system elements can be expected (Schneidewind and Augenstein 2016; Seto et al. 2016). Nevertheless, for the purpose of this conceptualization, we follow Gailing’s (2016) application of Foucault’s thoughts on a socio-technical system and argue that materialities, institutions, and practices play a crucial role in the socio-technical configuration, “but only gain importance in a broader context of […] discourses” (p. 247).

Empirically, the regime dimension can be characterized by an institutionalized discourse, represented by dominant narratives that are reproduced by a coalition of incumbent actors with strong discursive agency (see Leipold and Winkel 2016, for an example on the US wood industry). However, the degree of structuration of the institutionalized discourse is not static and can change over time, for example through changes in the related meta-discourse or due to the discursive struggle with an alternative discourse (Kaufmann and Wiering 2021). Consequently, regimes can be less structured and semi-coherent (Rosenbloom 2018) and tensions between incumbents’ narratives may emerge (Bosman et al. 2014). Over time, the narratives, as well as the coalition of (incumbent) discursive agents, might alter at the regime dimension, with consequent changes in material artifacts, institutions, and established practices.

Alternative discourses at the niche dimension

The niche dimension characterizes the other end of the continuum of structuration. Here, alternative socio-technical configurations are formed and the development of structuration is an ongoing process (Fuenfschilling and Truffer 2014; Smith and Raven 2012). Adding a discursive perspective, the niche dimension is related to alternative discourses. Presented through marginal or radical narratives by weak discursive agents, these ideas do net yet hold power in themselves, but rather, emerge out of a reaction to and are influenced by the structures at the regime and landscape dimensions. Therefore, multiple alternative discourses can emerge in relation to the same institutionalized discourse. As presented in Fig. 1, these alternative discourses can be at different degrees of structuration. There may be radical narratives representing a completely new innovation, or marginal narratives representing a slightly alternative approach that does not disrupt the dominant view, as well as everything in between. These alternative discourses compete with the institutionalized discourse as well as with each other. In the transition literature, the difference between radical and marginal narratives has been captured by Smith and Raven (2012), who talk about fit-and-conform and stretch-and-transform narratives, as different approaches for alternative narratives to compete with the regime. Learning from the interpretative discourse literature, the success of an alternative narrative not only depends on its attractiveness and legitimacy, but also on the strength of the discursive agents reproducing it. For example, Simoens and Leipold (2021) show that narratives reproduced by non-incumbent actors with weak discursive agency were not included in the policy discussions on a new German packaging regulation.

There are also alternative discourses possible that emerge as a reaction to a meta-discourse, and stand outside of this context (e.g. anarchy). These are not system specific, but rather, they offer a generally different perspective based on alternative values and assumptions (see Fig. 1).

A conceptualization of discursive lock-in mechanisms

The conceptualization of discursive elements and dynamics in socio-technical systems allows further exploring the role of these dynamics in transitions. At the core of transition research are the concepts path dependency and lock-in, which provide insights into the mechanisms that induce persistent stability and that need to be overcome or unlocked to foster change toward sustainability (Grin et al. 2010; Loorbach et al. 2017). Historical developments may shape various positive feedback mechanisms and create self-reinforcing mechanisms that reproduce – and lock-in the current socio-technical configuration (Arthur 1994; Foxon 2014; Klitkou et al. 2015). This self-reinforcing nature is the characteristic that distinguishes lock-in mechanisms from other transition barriers or overall inertia (Kotilainen et al. 2019). Scholars mainly conceptualize and analyze lock-in mechanisms related to the material artifacts, institutions, and established practices of a socio-technical system (Klitkou et al. 2015; Kotilainen et al. 2019; Seto et al. 2016). So far, discursive lock-ins have been overlooked (Buschmann and Oels 2019). Consequently, while the literature provides clear and accessible categorizations of material, institutional and behavioral lock-in mechanisms (for a comprehensive overview see Kotilainen et al. 2019; Seto et al. 2016), these are missing for the discursive counterpart. This development is crucial as, “understanding how and when lock-in emerges also helps identify windows of opportunity when transitions […] are possible” (Seto et al. 2016, p. 446).

This paper proposes a first list of discursive lock-in mechanisms. In line with Buschmann and Oels (2019), we understand a discourse as locked-in when its dynamics of discursive reproduction become self-reinforcing, shaping a persistent perception of reality. In other words, the institutionalized discourse or “the temporarily fixed rules of the game” (Leipold and Winkel 2017, p. 523) becomes automatically reproduced. To conceptualize how this self-reinforcement takes place and where to find it in the socio-technical system, we build on the heuristic of discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system outlined earlier in this paper as well as on empirical examples in the literature. In the following paragraphs, we identify three discursive dynamics that are self-reinforcing and consequently lock-in the institutionalized discourse, generate discursive inertia and prevent socio-technical change. Figure 1 indicates where in the socio-technical system these discursive lock-in mechanisms are situated.

Discursive lock-in 1: unchallenged values and assumptions of meta-discourses

Exploring the interpretative discourse literature shows that while meta-discourses are abstract and often not consciously discussed in society, they are nevertheless very powerful as they set the context for the discursive struggle between various perceptions of reality. Discursive agents and narratives that build on the values and assumptions of a meta-discourse automatically possess more influential characteristics compared to those aligned with different values and assumptions. Consequently, an institutionalized discourse that reproduces the same perception of reality as a meta-discourse will go largely unquestioned and be perceived as the best and only way in the socio-technical system. In this situation, the institutionalized discourse holds so much power in itself that other voices are excluded, confrontation with alternative ideas is avoided, and underlying values and assumptions are no longer critically challenged and discussed. Moreover, if the institutionalized discourse is closely aligned with the values and assumptions of meta-discourses, these discourses at an abstract level versus a more specific level—will mutually exchange confirmation and reproduction of the narratives, granting discursive agency to the actors reproducing them. In this way, the unchallenged values and assumptions of the meta-discourses create contexts in which institutionalized discourses are automatically reproduced and reinforced. A clear example of this lock-in are the unchallenged values and assumptions of the meta-discourse ecological modernization (as explained in “Meta-discourses at the landscape dimension”) in a circular economy policy context. Leipold (2021) argues the circular economy discourse at the European Union “was created to transform EU policy discourses ‘from within’ but eventually perpetuated the established discourse of ecological modernization” (p. 1). Ampe et al. (2019) show how ecological modernization limits the transformational potential of circular strategies and only leaves room for incremental change.

Discursive lock-in 2: incumbents’ strong discursive agency

A second self-reinforcing discursive lock-in mechanism is the power of incumbents’ strong discursive agency to reproduce the institutionalized discourse. In any struggle between institutionalized and alternative discourses, incumbent actors will play an important role as they will automatically be perceived as strong discursive agents through their mandates, knowledge, expertise, or other personal or positional characteristics. In other words, the use of strategic practices that enhance the reproduction of their narratives and consequent perception of reality will be more successful by incumbents than by non-incumbents with weaker discursive agency. Again, the study of Simoens and Leipold (2021) on the policy-making process of the 2019 German Packaging Act provides an empirical example, showing that the same actors that implemented the old packaging waste management regulation were involved in the policy-making process of the new regulation. As the old regulation gave these incumbent agents their personal and positional characteristics, they aimed to keep (or improve) their power in the socio-technical system by reproducing at least to a large extent the narratives of this already institutionalized discourse. Consequently, strong discursive agents will lock-in the institutionalized discourse to protect their responsibilities, resources, and positions in the system.

Discursive lock-in 3: narrative co-optation

The persistent reproduction or lock-in of the institutionalized discourse can also result from the discursive dilemma between radical or marginal narratives (Hajer 1995). In any discursive struggle with the institutionalized discourse, alternative narratives can present radically new ideas, with the risk of not being reproduced by any discursive agent, or they can speak within the format of the institutionalized discourse, with a higher chance of being sufficiently reproduced to become influential. However, the marginal narratives hold the risk of being co-opted by the dominant narrative. In other words, if the marginal narrative aligns too closely with the dominant narrative to convince incumbent discursive agents it loses its transformational power. Consequently, the reproduction of this marginal narrative locks in the institutionalized discourse rather than changing it. For example, Williams (2020) analyses the discursive struggle around hydropower in transboundary rivers in Asia and shows how alternative discourses on climate change governance and sustainable development are co-opted to support the dominant narratives advocating for hydropower as a renewable energy. Alternatively, marginal narratives can be co-opted by strong discursive agents aiming to address some changes in the meta-discourse such as more focus on sustainability to remain influential. In this way, the core values and assumptions of their narrative remain the same, and only minor or no changes in the established practices, institutions and material artifacts can be identified.

Unlocking pathways of discursive change

Unlocking self-reinforcing institutionalized discourses and enabling discursive change is crucial to enhance sustainability transitions. This heuristic shows the variety of discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system and conceptualizes a first understanding of how and where discursive lock-in mechanisms emerge and may hinder change. Based on these insights, this next section explores three ideal–typical pathways of discursive change that may provide insights on potential windows of opportunity to unlock the discursive configuration. To do so, we build on the current understanding of discursive lock-in (as presented by Buschmann and Oels 2019, and further developed in this paper) as well as insights of the interpretative discourse literature on discursive change. We link these insights with the transition scholars’ concept of pathways. Following the definition of Turnheim et al. (2015), pathways are “patterns of change in socio-technical systems unfolding over time that lead to new ways of achieving specific societal functions” (p. 240). Adding the discursive perspective, we understand pathways as patterns of discursive change, where the discursive struggle between the various discursive elements, allows for a new or different institutionalized discourse leading to alternative material artifacts, institutions, and established practices. We do not aim to provide a rigid framework or clear-cut unlocking strategies, but rather, we present an overview of potential pathways of discursive change and of how discursive lock-in can potentially be overcome in a socio-technical setting. This overview may serve the transition community as a starting point and guidance for future empirical work on the role of discursive change for sustainability transitions.

We name a first pathway disruptive discursive change. This refers to discursive change resulting from exogenous events, such as natural disasters, that alter the values and assumptions of the meta-discourse (Buschmann and Oels 2019). By themselves these events have no inherent meaning, but are socially constructed into discursive events (Hajer 1995). For instance, Hermwille (2016) shows how different countries variously translated the meaning of the nuclear catastrophe of Fukushima into their values and assumptions about nuclear energy. Consequently, this variation in discursive translation led to different degrees of discursive change at the landscape level and policy change in the countries. In sum, disruptive discursive change may unlock the unchallenged values and assumptions of the meta-discourse and create a change in the context of the discursive elements and dynamics of the socio-technical system, providing opportunities for alternative discourses to gain dominance.

A second pathway dynamic discursive change refers to change from within. Although it is still debated if discursive change from within can only lead to incremental transitions or whether it holds the potential for radical change (Ferguson 2015; Leipold 2021), the discursive literature projects different streams within this pathway that may lead to a dynamic variation of discursive change. One stream focuses on disclosing the underlying values and assumptions of the meta-discourse more actively, in order to challenge its meaning structures for example, as Machin (2019) argues for the win–win message of ecological modernization. Taking a closer look behind buzzwords like “sustainability” or “circular economy” may inform changes in the discursive struggle and make the meta-discourse a more active part of the discursive struggle (Leipold et al. 2021). Alternatively, dynamic discursive change may be achieved by opening up the discursive struggle for alternative narratives as well as making these attractive for incumbent agents and consequently destabilizing the institutionalized discourse. As Bosman et al. (2014) argue, “storylines in the making are not merely innocent language, but can lead to discursive repositioning among incumbents with implications for the coherence of the regime” (p. 56). For example, various participatory methods can be used to include “unheard” narratives more prominently in the discursive struggle (Marquardt et al. 2021); or new narratives may be created that aim to build trust and provide space to discuss conflicts that arise from a transition by default (Luo et al. 2021). Moreover, presenting clear directions and goals of a desired transition may help to convince strong discursive agents from an alternative discourse (Simoens and Leipold 2021). A last dynamic stream focuses on unlocking the discursive agency of incumbents by breaking power asymmetries (Buschmann and Oels 2019) or delegitimizing parts of incumbent groups (Leipold and Winkel 2016). For instance, Williams (2020) points to the relevance of adding new actors with new ideas to the discursive struggle, and Leipold (2021) stresses the need for new discursive agents that can struggle “at eye-level” with the incumbents for discursive change. Rethinking the process of (environmental) policy-making as well as addressing the concerns of strong incumbent actors who might be the losers of a sustainability transition (e.g., fossil fuel industries) may help to enable discursive change. In sum, the various streams of dynamic discursive change can address different discursive lock-in mechanisms simultaneously, creating an altered discursive configuration that may lead to a transition in the overall socio-technical system.

A third pathway is cross-sectoral discursive change, which builds on the idea of deliberative learning between various socio-technical systems. Buschmann and Oels (2019) argue that “deliberative processes need to encourage understanding and learning across discourses” (p. 4). In a socio-technical setting, this deliberation may happen between related socio-technical systems (e.g., energy and mobility). The effects of disruptive or dynamic discursive change in one socio-technical system may consequently create change in the structuration of another system.

This overview of discursive change pathways shows that there is no single best or obvious strategy to unlock discursive lock-in mechanisms and to enable discursive change. While disruptive change may enable radical transitions, it may also depend on undesirable shocking events to open up the discursive struggle. Furthermore, while dynamic change may enable transitions on the long run, it risks fostering only incremental change. The same holds for cross-sectoral change, while depending on successful transitions elsewhere. This overview shows there is not only one unlocking pathway for each lock-in mechanism, but rather, there are various pathways to unlock the overall discursive configuration. Depending on the empirical context and the degree of structuration of the socio-technical system at a given time, these approaches one or multiple ones may present a window of opportunity to enable discursive change.

Discussion and conclusions

To support the exchange between interpretative discourse literature and sustainability transition research, this paper explores the role of discursive elements and dynamics for stability and change in a socio-technical system. To conclude this study, we discuss the added value of this discursive perspective for transition research and governance.

First, this paper offers additional analytical approaches and concepts for discursive studies in sustainability transition research. So far, interpretative discourse analysis has mainly been used to analyze processes of sense-making in transitions. However, the exploration of discursive elements and dynamics in this paper shows that the large potential of interpretative discourse approaches lies in the analysis of how discourses shape the established practices, institutions, and material artifacts of a socio-technical system. In other words, discursive studies can enhance the understanding of why a system is configured as it is as well as how and why a system has or has not changed over time. Furthermore, the overview of discursive elements and dynamics point to the inseparableness of narratives and discursive agency. While the transition literature on narratives is more developed (Hermwille 2016; Roberts 2017; Rosenbloom et al. 2016; Smith and Raven 2012), the role of discursive agency remains unexplored. Building on the Discursive Agency Approach, concrete analytical concepts such as the attribution of characteristics or the use of strategic practices can be used to understand what makes an actor into a (discursive) agent and how they influence the transition process. These concepts may complement the current conceptualization of agency in transition research (for an overview see Fischer and Newig 2016; Köhler et al. 2019) as well as deepen the empirical understanding of the characteristics and strategic practices of incumbent and innovative actors in shaping the socio-technical configuration. These analytical tools may enhance the understanding of discursive struggles in sustainability transition processes and form an opportunity to shift the research focus from narratives solely to the interactions between narratives and discursive agents. It is the combination of an influential narrative with a strong discursive agent that forms a key condition for change (Lang et al. 2019; Leipold et al. 2016).

Second, the discursive perspective on a socio-technical system elaborates on the understanding of the dynamics within and between the various analytical dimensions. For instance, the heuristic points to the crucial role of meta-discourses at the landscape level in shaping the context for the other dimensions. Consequently, we support the claim of “deep transitions” scholars and argue that a change in the values and assumptions of the meta-discourse at the landscape dimension is crucial for successful sustainability transitions (Kanger and Schot 2019; Schot and Kanger 2018; van der Vleuten 2019). Although changes at the meta-discourse only appear slowly, they are very powerful in shaping the context for the other discursive elements to emerge and develop. We suggest that incorporating the discursive landscape dynamics is important to understand the socio-technical configuration as a whole. Its systematic empirical analysis may support a more critical understanding of the values and assumptions driving sustainability transitions, as is also suggested by Feola (2019) on the role of capitalism, and may allow an exchange between various conflicting transition narratives (Luederitz et al. 2017). This systematic analysis may also inform practical action and transition governance. For example, it could support strategic planning and scenario building following the methods of causal layered analysis (Inayatullah 1998) or at least bring the various values that underlie such concepts as sustainability back to the core of the debate (Machin 2019). Furthermore, the heuristic shows that there is a variety of niche-constellations possible, based on their level of structuration. Interpretative discourse analysis and transition research are aligned in the approach that it is the niche dimension that forms the main arena for potential change (Augenstein et al. 2020; Hajer 1995). However, in empirical transition research niches are often conceptualized as innovations that are completely new to the system (Smith and Raven 2012). By applying a discursive perspective we can differentiate between alternative discourses based on their relation to the institutionalized discourse; they may hold marginal narratives, radical narratives, or any form in between. In other words, we argue that alternative discourses need not only be built around new ideas, but can also arise from longstanding narratives that never became dominant but are still reproduced by certain (weak) discursive agents. Macnaghten et al. (2019), for instance, show that while technologies may be completely new and create a new niche, people may use “modern” as well as “ancient” narratives to make sense of them. A discursive perspective may help to capture, also empirically, the diversity of elements and dynamics of a socio-technical system.

Third, the heuristic supports a theoretical conceptualization of discursive lock-in mechanisms and points out the relevance of a discursive perspective for successful transition acceleration and governance. Building further on the work of Buschman and Oels (2019) and the discursive perspective of a socio-technical system presented in this paper, we conceptualize three self-reinforcing mechanisms that lock-in the institutionalized discourse and its consequent established practices, institutions, and material artifacts. In this way, we show that the unchallenged values and assumptions of meta-discourses, incumbents’ discursive agency, and narrative co-optation are three discursive lock-in mechanisms that need to be addressed when aiming for successful sustainability transitions. The mechanisms show that transitions are hindered not only at the regime level, as is often assumed in transition studies (Geels 2004; Loorbach et al. 2017), but that resistance to change may originate at various degrees of structuration. Consequently, the unlocking of the institutionalized discourse requires a systems perspective, building on a variety of pathways of discursive change. Additionally, the discursive lock-in mechanisms do not stand alone but need to be understood in the broader socio-technical perspective. In other words, these discursive mechanisms may mutually reinforce each other as well as may be interlinked with material, institutional, or behavioral lock-in mechanisms. From a discursive perspective, Buschmann and Oels (2019) argue that “discourse actually underlies lock-in in the realms of infrastructures, institutions, and behavior—it also connects and aligns them” (p. 11). Future research may analyze to what extend the discursive lock-in mechanisms conceptualized in this paper shape and create lock-in mechanisms in the other system elements. Additionally, Seto et al. (2016) suggests: “efforts to break from one type of lock-in result in hardening or compensating resistance to change in other types of lock-in” (p. 427). Therefore, future empirical research may create great value in a better understanding of the interlinkages between lock-in mechanisms in the various system components and help to grasp the socio-technical system in its complexity. We hope this theoretical conceptualization can serve as a baseline for further empirical inquiry of discursive lock-in mechanisms as well as may support further research on entry points for decision-makers and practitioners to address discursive, institutional, behavioral, and material lock-ins in an integrative manner, a precondition for successful transition governance (Schneidewind and Augenstein 2016).

We hope that the proposed conceptualization of discursive elements, dynamics, lock-ins, and change pathways in a socio-technical system will support transition researchers in applying the full spectrum of theoretical concepts and insights that interpretative discourse analysis has to offer. By providing a review of the core discursive elements, their interactions and dynamics in a socio-technical system, as well as a conceptualization of their self-reinforcing lock-in mechanisms explaining persistent stability from a discursive perspective and three potential pathways to unlock and enable change, we consider this study a heuristic for new empirical research rather than a new theoretical framework. We aim to highlight that there are many possible interesting points of exchange between the interpretative discourse literature and sustainability transition research. Certainly, a fruitful exchange of ideas and insights requires further theoretical and conceptual engagement as well as empirical applications. Therefore, this paper is to be read and discussed as a first step in shifting focus toward a more systematic analysis of discursive elements and dynamics in a socio-technical system, with the aim to enhance the understanding of the dynamics of stability and change and to support a systemic approach to sustainability transition acceleration and governance.

References

Ampe K, Paredis E, Asveld L, Osseweijer P, Block T (2019) A transition in the Dutch wastewater system? The struggle between discourses and with lock-ins a transition in the Dutch wastewater system? J Environ Policy Plan 22:155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1680275

Arthur WB (1994) Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Augenstein K, Bachmann B, Egermann M, Hermelingmeier V, Hilger A, Jaeger-Erben M, Kessler A, Lam DPM, Palzkill A, Suski P, von Wirth T (2020) From niche to mainstream: the dilemmas of scaling up sustainable alternatives. GAIA Ecol Perspect Sci Soc 29:143–147. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.29.3.3

Bäckstrand K, Lövbrand E (2006) Planting trees to mitigate climate change: contested discourses of ecological modernization, green governmentality and civic environmentalism. Glob Environ Polit 6:50–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2006.6.1.50

Berger PL, Luckmann T (1966) The social construction of reality. Doubleday and Company, New York

Bosman R, Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Pistorius T (2014) Discursive regime dynamics in the Dutch energy transition. Environ Innov Soc Transit 13:45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2014.07.003

Buschmann P, Oels A (2019) The overlooked role of discourse in breaking carbon lock-in: the case of the German energy transition. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 10:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.574

Carstensen MB, Schmidt VA (2016) Power through, over and in ideas: conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. J Eur Public Policy 23:318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

Dryzek JS (2013) The politics of the earth: environmental discourses. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fairclough N (2012) Critical Discourse Analysis. Int Adv Eng Technol 7:452–487. https://doi.org/10.9753/icce.v16.105

Feola G (2019) Capitalism in sustainability transitions research: time for a critical turn? Environ Innov Soc Transit 35:241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.005

Feola G, Jaworska S (2019) One transition, many transitions? A corpus-based study of societal sustainability transition discourses in four civil society’s proposals. Sustain Sci 14:1643–1656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0631-9

Ferguson P (2015) The green economy agenda: business as usual or transformational discourse ? Environ Polit 24:17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.919748

Fischer F, Forester J (1993) The argumentative turn in policy and planning. Duke University Press, Durham

Fischer L-B, Newig J (2016) Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: a systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability 8:476–497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050476

Fischer F, Torgerson D, Durnová A, Orsini M (2015) Introduction to critical policy studies. Handbook of ciritical policy studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Foucault M (1972) The archeology of knowledge. Tavistock Publications Limited, London

Foxon TJ (2014) Technological lock-in and the role of innovation. In: Atkinson G, Dietz S, Neumayer E (eds) Handbook of sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 140–152

Fuenfschilling L, Truffer B (2014) The structuration of socio-technical regimes: conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res Policy 43:772–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010

Fuenfschilling L, Truffer B (2016) The interplay of institutions, actors and technologies in socio-technical systems - An analysis of transformations in the Australian urban water sector. Technol Forecast Soc Change 103:298–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.023

Gailing L (2016) Transforming energy systems by transforming power relations. Insights from dispositive thinking and governmentality studies. Innov Eur J Soc Sci Res 29:243–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2016.1201650

Geels FW (2004) From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res Policy 33:897–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

Geels FW (2010) Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res Policy 39:495–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.022

Geels FW (2014) Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory Cult Soc 31:21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

Geels FW, Verhees B (2011) Cultural legitimacy and framing struggles in innovation journeys: A cultural-performative perspective and a case study of Dutch nuclear energy (1945–1986). Technol Forecast Soc Change 78:910–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.12.004

Geels FW, Berkhout F, Van Vuuren DP (2016) Bridging analytical approaches for low-carbon transitions. Nat Clim Chang 6:576–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2980

Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J (2010) Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge, New York

Hajer M (1995) The politics of environmental discourse: ecological modernisation and the policy process. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Hajer M (2006) Doing discourse analysis: coalitions, practises, meaning. In: Van den Brink M, Metze T (eds) Discourse theory and method in the social sciences. Netherlands Graduate School of Urban and Regional Research, Utrecht, pp 65–76

Hajer M, Versteeg W (2005) A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: achievements, challenges, perspectives. J Environ Policy Plan 7:175–184

Hermwille L (2016) The role of narratives in socio-technical transitions-Fukushima and the energy regimes of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Energy Res Soc Sci 11:237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.11.001

Inayatullah S (1998) Causal layered analysis: poststructuralism as method. Futures 30:815–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X

Isoaho K, Karhunmaa K (2019) A critical review of discursive approaches in energy transitions. Energy Policy 128:930–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.043

Kanger L, Schot J (2019) Deep transitions: theorizing the long-term patterns of socio-technical change. Environ Innov Soc Transit 32:7–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.006

Kaufmann M, Wiering M (2021) The role of discourses in understanding institutional stability and change: an analysis of Dutch flood risk governance. Glob Environ Chang 44:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1935222

Keller R (2011) The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse (SKAD). Hum Stud 34:43–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-011-9175-z

Keller R (2012) Doing discourse research: an introduction for social scientists. Sage, London

Kern F (2011) Ideas, institutions, and interests: Explaining policy divergence in fostering “system innovations” towards sustainability. Environ Plan C 29:1116–1134. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1142

Klitkou A, Bolwig S, Hansen T, Wessberg N (2015) The role of lock-in mechanisms in transition processes: the case of energy for road transport. Environ Innov Soc Transit 16:22–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.005

Köhler J, Geels FW, Kern F, Markard J, Onsongo E, Wieczorek A, Alkemade F, Avelino F, Bergek A, Boons F, Fünfschilling L, Hess D, Holtz G, Hyysalo S, Jenkins K, Kivimaa P, Martiskainen M, Mcmeekin A, Mühlemeier MS, Nykvist B, Pel B, Raven R, Rohracher H, Sandén B, Schot J, Sovacool B, Turnheim B, Welch D, Wells P (2019) An agenda for sustainability transitions research: state of the art and future directions. Environ Innov Soc Transit 31:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

Kotilainen K, Aalto P, Valta J, Rautiainen A, Kojo M, Sovacool BK (2019) From path dependence to policy mixes for Nordic electric mobility: Lessons for accelerating future transport transitions. Policy Sci 52:573–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11077-019-09361-3

Kriechbaum M, Posch A, Hauswiesner A (2021) Hype cycles during socio-technical transitions: The dynamics of collective expectations about renewable energy in Germany. Res Policy 50:104262. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESPOL.2021.104262

Lang S, Blum M, Leipold S (2019) What future for the voluntary carbon offset market after Paris? An explorative study based on the Discursive Agency Approach. Clim Policy 19:414–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1556152

Leipold S (2021) Transforming ecological modernization ‘from within’ or perpetuating it? The circular economy as EU environmental policy narrative. Environ Polit. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1868863

Leipold S, Winkel G (2016) Divide and conquer-Discursive agency in the politics of illegal logging in the United States. Glob Environ Chang 36:35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.006

Leipold S, Winkel G (2017) Discursive agency: (re-) conceptualizing actors and practices in the analysis of discursive policymaking. Policy Stud J 45:510–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12172

Leipold S, Sotirov M, Frei T, Winkel G (2016) Protecting “first world” markets and “third world” nature: the politics of illegal logging in Australia, the European Union and the United States. Glob Environ Chang 39:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.06.005

Leipold S, Feindt PH, Winkel G, Keller R (2019) Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: traditions, trends, perspectives. J Environ Policy Plan 21:445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

Leipold S, Petit-Boix A, Luo A, Helander H, Simoens M, Ashton W, Babbitt C, Bala A, Bening C, Birkved M, Blomsma F, Boks C, Boldrin A, Deutz P, Domenech T, Ferronato N, Gellego-Schmid A, Giurco D, Hobson K, Husgafvel R, Isenhour C, Kriipsalu M, Masi D, Mendoza JMF, Milios L, Niero M, Pant D, Pauliuk S, Pieroni M, Richter J, Saidani M, Smol M, Talens Pieró L, Van Ewijk S, Vermeulen W, Wiedenhofer D, Xue B (2021) Lessons, narratives and research directions for a sustainable circular economy. Researchsquare. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-429660/v1

Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Avelino F (2017) Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practise for societal change. Annu Rev Environ Resour 42:599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ

Luederitz C, Abson DJ, Audet R, Lang DJ (2017) Many pathways toward sustainability: not conflict but co-learning between transition narratives. Sustain Sci 12:393–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0414-0

Luo A, Zuberi M, Liu J, Perrone M, Schnepf S, Leipold S (2021) Why common interests and collective action are not enough for environmental cooperation–Lessons from the China-EU cooperation discourse on circular economy. Glob Environ Chang 71:102389. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2021.102389

Machin A (2019) Changing the story? The discourse of ecological modernisation in the European Union. Environ Polit 28:208–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549780

Macnaghten P, Davies SR, Kearnes M (2019) Understanding public responses to emerging technologies: a narrative approach. J Environ Policy Plan 21:504–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1053110

Markard J, Raven R, Truffer B (2012) Sustainability transitions: an emerging field of research and its prospects. Res Policy 41:955–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

Marquardt J, Nasiritousi N, Marquardt J (2021) Imaginary lock-ins in climate change politics: the challenge to envision a fossil-free future challenge to envision a fossil-free future. Environ Polit 00:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1951479

Münch S (2015) Interpretative policy-analyse: eine Einführung. Springer, Berlin

Roberts JCD (2017) Discursive destabilisation of socio-technical regimes: Negative storylines and the discursive vulnerability of historical American railroads. Energy Res Soc Sci 31:86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.031

Rosenbloom D (2018) Framing low-carbon pathways: a discursive analysis of contending storylines surrounding the phase-out of coal-fired power in Ontario. Environ Innov Soc Transit 27:129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.11.003

Rosenbloom D, Berton H, Meadowcroft J (2016) Framing the sun: a discursive approach to understanding multi-dimensional interactions within socio-technical transitions through the case of solar electricity in Ontario. Can Res Policy 45:1275–1290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.03.012

Schneidewind U, Augenstein K (2016) Three schools of transformation thinking: The impact of ideas, institutions, and technological innovation on transformation processes. Gaia 25:88–93. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.25.2.7

Schot J, Kanger L (2018) Deep transitions: emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Res Policy 47:1045–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.009

Scrase JI, Ockwell DG (2010) The role of discourse and linguistic framing effects in sustaining high carbon energy policy: an accessible introduction. Energy Policy 38:2225–2233. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENPOL.2009.12.010

Sengul K (2019) Critical discourse analysis in political communication research: a case study of right-wing populist discourse in Australia. Commun Res Pract 5:376–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2019.1695082

Seto KC, Davis SJ, Mitchell RB, Stokes EC, Unruh G, Urge-Vorsatz D (2016) Carbon lock-in: types, causes, and policy implications. Annu Rev Environ Resour 41:425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085934

Simoens MC, Leipold S (2021) Trading radical for incremental change: the politics of a circular economy transition in the German packaging sector. J Environ Policy Plan. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1931063

Smith A, Raven R (2012) What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res Policy 41:1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

Sovacool BK, Hess DJ (2017) Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change. Soc Stud Sci 47:703–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717709363

Stone D (1989) Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Polit Sci Q 104:281–300

Turnheim B, Berkhout F, Geels F, Hof A, McMeekin A, Nykvist B, van Vuuren D (2015) Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Glob Environ Chang 35:239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.010

van der Vleuten E (2019) Radical change and deep transitions: Lessons from Europe’s infrastructure transition 1815–2015. Environ Innov Soc Transit 32:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.12.004

Williams JM (2020) Discourse inertia and the governance of transboundary rivers in Asia. Earth Syst Gov 3:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2019.100041

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the financial support by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 031B0018, as part of the research group “Circulus—Opportunities and challenges of transition to a sustainable circular bio-economy”. Lea Fuenfschilling gratefully acknowledges funding from the Swedish Transformative Innovation Policy Platform funded by VINNOVA, grant no 2017-01600.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. MS took the lead in the investigation and the writing of the manuscript. LF and SL provided substantial input during the development, analysis, and interpretation, and critically reviewed and edited the text. All authors gave their final approval to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by David J. Abson, Leuphana Universitat Luneburg, Germany.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simoens, M.C., Fuenfschilling, L. & Leipold, S. Discursive dynamics and lock-ins in socio-technical systems: an overview and a way forward. Sustain Sci 17, 1841–1853 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01110-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01110-5