Abstract

Background

There are concerns about the capacity of rural primary care due to potential workforce shortages and patients with disproportionately more clinical and socioeconomic risks. Little research examines the configuration and delivery of primary care along the spectrum of rurality.

Objective

Compare structure, capabilities, and payment reform participation of isolated, small town, micropolitan, and metropolitan physician practices, and the characteristics and utilization of their Medicare beneficiaries.

Design

Observational study of practices defined using IQVIA OneKey, 2017 Medicare claims, and, for a subset, the National Survey of Healthcare Organizations and Systems (response rate=47%).

Participants

A total of 27,716,967 beneficiaries with qualifying visits who were assigned to practices.

Main Measures

We characterized practices’ structure, capabilities, and payment reform participation and measured beneficiary utilization by rurality.

Key Results

Rural practices were smaller, more primary care dominant, and system-owned, and had more beneficiaries per practice. Beneficiaries in rural practices were more likely to be from high-poverty areas and disabled. There were few differences in patterns of outpatient utilization and practices’ care delivery capabilities. Isolated and micropolitan practices reported less engagement in quality-focused payment programs than metropolitan practices. Beneficiaries cared for in more rural settings received fewer recommended mammograms and had higher overall and condition-specific readmissions. Fewer beneficiaries with diabetes in rural practices had an eye exam. Most isolated rural beneficiaries traveled to more urban communities for care.

Conclusions

While most isolated Medicare beneficiaries traveled to more urban practices for outpatient care, those receiving care in rural practices had similar outpatient and inpatient utilization to urban counterparts except for readmissions and quality metrics that rely on services outside of primary care. Rural practices reported similar care capabilities to urban practices, suggesting that despite differences in workforce and demographics, rural patterns of primary care delivery are comparable to urban.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Primary care aims to deliver care that is a patients’ first contact, comprehensive, and coordinated, and offers continuity between clinicians and patients.1,2,3,4,5 Pressure on primary care clinicians to assume responsibility for population health, outcomes, and costs has increased over the past decade.6,7,8 Despite the recognition that high-quality primary care is an important determinant of health, problems persist: access to primary care is uneven,9 supply of primary care physicians is decreasing,10,11 patients are increasingly complex,12,13,14 and primary care is under-resourced. There are just 3 primary care physicians per 10,000 people in non-metropolitan areas compared with 8 in metropolitan areas.15 The workload for rural primary care clinicians is also greater because they typically deliver a wider range of services despite the reduced workforce.16,17,18

Policymakers have committed to addressing challenges around access to care in rural settings by tailoring existing payment and delivery policies with a rural “lens.”19 At the same time, provider organizations, including the American Medical Association, advocate policies aimed at increasing the supply of physicians in rural settings.20 Despite the increased focus and commitment to supporting rural primary care, we know strikingly little about how primary care is configured and delivered across rural settings. There are clear cultural and workforce differences across rural settings, yet research typically combines isolated, small towns, and suburban areas into a single rural category which may mask important differences. While there are fears about the ability of rural primary care to deliver coordinated and comprehensive care,18,21 there are few national studies examining care delivery capabilities of primary care practices across settings. Patients regularly report challenges to accessing primary care in rural settings,22,23 yet there is little research comparing the patterns of outpatient utilization.

In this paper, we seek to fill these gaps by exploring the configuration of primary care practices to understand the landscape of primary care delivery.

METHODS

We characterized physician practices and their Medicare beneficiaries across isolated, small town, micropolitan, and metropolitan settings in 2017.

Study Population and Data Sources

IQVIA’s OneKey database, which operationalizes the relationships between individual clinicians and practices, was used to define and characterize physician practices. OneKey nationally characterizes physician practices in terms of ownership, composition, number of physicians, and types of clinicians.24 OneKey is a proprietary database that relies on primary data collection efforts, the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile, and publicly available sources. The study population retains all IQVIA OneKey physician practices with assigned Medicare beneficiaries, regardless of size or specialty.

We used 2017 Medicare fee-for-service claims to understand more about the beneficiaries using each physician practice, and their travel and utilization patterns. We included beneficiaries with full, continuous part A and B coverage, 18–99 years of age, and residing in one of the 50 US states or Washington, DC. We excluded beneficiaries who turned 65 during 2017 due to inability to determine claims history. We adapted methods used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare Shared Savings Program to assign beneficiaries to the physician practice from IQVIA where they received the plurality of their outpatient evaluation and management visits. We prioritized visits to primary care clinicians over specialist clinicians in this assignment such that beneficiaries were only assigned to a specialist if they had no visits from a primary care clinician (family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, preventive medicine, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, physician assistant). Only beneficiaries cared for by one of the OneKey identified physician practices were retained in our study population (86.5% of beneficiaries with evaluation and management visits).

NSHOS, fielded between June 2017 and August 2018, is a nationally representative set of surveys including a survey of physician practices with at least three adult primary care physicians.25,26,27,28,29 NSHOS surveyed a sample of the IQVIA OneKey identified physician practices. Adult primary care physicians included family medicine, geriatrics, internal medicine, and preventive medicine specialties. NSHOS collected information on practices’ structure, ownership, leadership, care delivery capabilities, and participation in delivery reform. NSHOS used a stratified-cluster sampling design that sampled both system-owned and independent physician practices. NSHOS targeted practice managers, physicians, or practice leadership as respondents. NSHOS surveyed 4,976 physician practices; 2,333 practices responded to the survey for a response rate of 46.9%. We excluded 143 practices due to item nonresponse for a total of 2,190 analyzed practices.

Measures

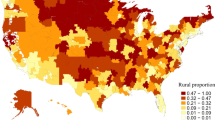

Beneficiaries’ residence and practices were classified as isolated (<2,500 people; RUCA 10), small town (2,500-9,999 people; RUCA 7-9), micropolitan (10,000-49,999; RUCA 4-6), or metropolitan (>50,000 people; RUCA 1-3) using the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes. Isolated, small town, and micropolitan areas are commonly used to define “rural.”

Using the OneKey data, we described all US practices according to structural, workforce, and geographic characteristics (Table 1). For the NSHOS sample, we further characterized care delivery capabilities using composite scores summarizing the degree to which physician practices report engaging in care delivery processes on responses on payment and delivery reform participation.29 The standardized composites average component questions across various domains relating to patient screening, care activities, and practice engagement in reform activities, among other domains.

Using Medicare claims and U.S. Census data, we characterized beneficiaries across rural settings according to their (1) demographics, (2) clinical conditions using hierarchical condition categories, and (3) area-level measures from U.S. Census (Table 3).

We then compared utilization across rural settings including (1) inpatient stays, (2) emergency department visits, (3) outpatient visits, (4) diabetes quality metrics, (5) mammograms, (6) percentage that died, and (6) payments (Table 4).

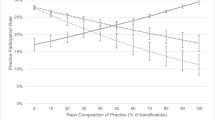

Finally, we considered the proportion of all beneficiaries residing within each rural setting that were cared for by practices located across settings (Figure 1). We computed the straight-line distance in miles between beneficiaries’ ZIP code to the ZIP code of their assigned practice.

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted an unadjusted, descriptive analysis of practices to assess organizational differences between isolated, small town, micropolitan, and metropolitan settings (Table 1). To characterize the capabilities of the NSHOS sample of physician practices, we performed unadjusted, descriptive analyses using NSHOS (Table 2). NSHOS analyses used probability weights so that the estimated means and proportions accounted for sampling and non-response and corresponded to the practices included in OneKey. We used t-tests and chi-square tests to assess significance.

Next, we performed unadjusted, descriptive analyses to characterize the demographic, clinical, and area-level characteristics of beneficiaries cared for by these practices (Table 3). To compare beneficiary hospital and outpatient utilization across settings, we performed linear and logistic regression modeling to adjust for beneficiary-level demographics, clinical characteristics, and hospital referral regions (adjusted means shown in Table 4; detailed regression output shown in the Appendix).

To estimate the adjusted proportions of beneficiaries residing within each rural setting that were assigned to isolated, small town, micropolitan, and metropolitan practices, we used multinomial logistic models (Figure 1; detailed output shown in the Appendix).

Models were adjusted for the beneficiary demographic (e.g., age, under 65, over 85, sex, race/ethnicity, disabled, dual eligible for Medicaid), clinical (number of chronic conditions, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, frail, nursing home resident, death), and area-level characteristics (household income, poverty level, hospital referral regions) shown in Table 3 (detailed measure definitions are shown in the Appendix).

Measures were created using SAS and analyses were conducted using Stata.

RESULTS

Practice Characteristics

Our study sample included a total of 116,879 physician practices. Of these, 2,185 (1.9%) were located in isolated settings, 4,502 (3.9%) in small town settings, 11,022 (9.4%) in micropolitan settings, and 99,170 (84.8%) in metropolitan settings (Table 1). Compared to metropolitan practices, isolated practices cared for more attributed Medicare beneficiaries per practice while isolated practices also typically had fewer physicians. Practices in more rural settings had a lower proportion of physicians specializing in internal medicine and a greater proportion in family medicine. Practices in isolated and small town settings were more primary care centric than those in micropolitan and metropolitan settings as evidenced by being less likely to have specialist physicians. Practices in rural settings were more likely to include a nurse practitioner, physician assistance, or clinical nurse specialist (30.5% of isolated practices compared with 20.5% of metropolitan practices). Isolated practices were more commonly owned by a health care system (45.6%) than small town (37.0%), micropolitan (33.4%), and metropolitan (34.2%) practices (Table 1).

Of these, 2,189 practices with three or more physicians responded to NSHOS with a similar distribution across rural settings. Regardless of setting, multi-physician practices reported similar capabilities for clinical screenings, managing complex patients, use of evidence-based guidelines, use of electronic health records for decision-making, use of registries, and approaches to physician management. Multi-physician practices in isolated and in micropolitan settings reported significantly less engagement in quality-focused payment programs than practices in metropolitan settings. Differences in quality-focused payment program participation was driven by lower self-reported engagement of isolated practices in accountable care organization (ACO) contracts (Table 2). Significantly fewer isolated (22%) and small town (29%) practices reported an anticipated majority of patients being covered by total cost of care contracts in 5 years, compared to micropolitan (52%) and metropolitan practices (43%; Table 2).

Beneficiary Characteristics

Comparing between practice settings, beneficiaries cared for by more rural practices were more often White, more likely to be disabled, dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and from areas with greater poverty. Beneficiaries cared for by metropolitan practices were more likely to have cancer, end-stage renal disease, frailty, and nursing facility care use (Table 3).

Utilization and Quality Measures

There were few substantive, clinically meaningful differences after risk adjustment across practice settings for most utilization measures including inpatient stays, emergency department visits, emergency department visits by necessity, and patterns of outpatient visits. Readmission measures were a noteworthy exception with beneficiaries in isolated and small town practices having higher 30-day readmission rates than those cared for in practices in micropolitan and metropolitan areas including for all-cause medical discharges, surgical discharges, heart failure discharges, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia discharges.

Fewer beneficiaries with diabetes cared for in rural practices had an annual eye exam (64.9% in isolated vs. 69.0% in metropolitan), yet similar proportions of beneficiaries with diabetes had a blood lipids and hemoglobin A1c tests. Fewer beneficiaries in isolated rural practices received a recommended mammogram (59.8%) compared with other settings (64.6% small town, 64.6% micropolitan, 65.3% in metropolitan).

Payments for beneficiaries cared for in isolated practices cost, on average (per beneficiary), $725 more than beneficiaries cared for in metropolitan practices after risk adjustment, with much of the difference due to higher payments for acute care in isolated settings (Table 4).

Access to Outpatient Care

Patterns of adjusted outpatient visits with primary care clinicians were strikingly similar between rural and non-rural settings. The number of visits per year with primary care clinicians was similar regardless of practice setting. While the overall visit rate was similar across settings, the share of visits with family medicine versus internists varied by rurality. Beneficiaries cared for by metropolitan practices had slightly more visits to specialist physicians than those cared for by isolated practices (5.0 vs. 4.3). Beneficiaries cared for in rural practices were more likely to have a follow-up outpatient visit after an inpatient stay than those cared for in non-rural practices.

Beneficiaries living in more rural areas were less likely to receive primary care in the setting where they resided: 37.5% of beneficiaries residing in isolated settings are cared for by practices within the same setting, compared to 55.9% of small town beneficiaries, 71.9% of micropolitan beneficiaries, and 96.6% of metropolitan beneficiaries (Figure 1). Beneficiaries traveled farther as they were cared for by practices in more populated settings than which they resided. Over a quarter (26.2%) of isolated beneficiaries were cared for by practices greater than 60 miles from their residence.

DISCUSSION

We found that rural practices have fewer physicians, are more primary care and family medicine oriented, have more nurse practitioners, and are more likely to be owned by a health care system. Despite concerns about rural practices’ capabilities, in part due to workforce shortages,30 we found that rural and non-rural multi-physician practices report similar care delivery capabilities. Patients in rural practices have similar utilization patterns for most measures with few noteworthy differences: rural practices have both higher adjusted readmission rates and greater follow-up visit rates after a hospital stay. Rural patients have similar access to care in terms of number of outpatient visits, yet they may experience greater challenges reaching care.

We found that the structure and configuration of physician practices varied among rural settings with practices in micropolitan areas more similar to those in metropolitan areas in terms of number of physicians, composition of physicians, and ownership. With fewer specialist clinicians available, primary care physicians in isolated areas face different challenges than physicians in micropolitan areas and may therefore benefit from different solutions. For example, isolated primary care clinicians may benefit more from virtual access to specialists (through, for example, the ECHO model31) while micropolitan primary care clinicians may need more robust referral networks in metropolitan areas.

We found that rural patients tend to travel farther for their care with a quarter of isolated patients traveling more than 60 miles. The increased travel burden among rural patients likely drives perceptions of inaccessibility. A recent survey found that one in four rural residents report not being able to access health care when they needed it—22% of those said it was too far or difficult to get care.22 Increased access to telehealth could relieve some of the travel burden that rural patients experience. Despite challenges accessing care, the number of outpatient encounters does not vary much across rural settings, indicating that patients may be getting the care they need, despite the increased burden.

Our findings suggest that, despite challenges, Medicare patients may be able to adequately access primary care services in rural settings. This finding aligns with and advances prior research showing adults under 65 report comparable access to office-based visits between rural and urban settings regardless of insurance status.32 Our study advances this prior research by disaggregating rurality into isolated, small town, and micropolitan settings and by examining access at the practice level. Yet, our finding that practices in rural settings have two to four times as many attributed Medicare beneficiaries (despite having, on average, fewer clinicians) than practices in urban settings lends support to concerns that the supply of primary care clinicians is inadequate in rural settings. The growth of nurse practitioners and other non-physician clinicians in rural settings has likely helped ensure patients can access care.33,34 Considering the rural health care workforce is aging and fewer new physicians join rural practices, policymakers should remain focused on ensuring there is a sufficient primary care workforce pipeline in rural settings.35 There has been concern that lack of access to primary care in rural settings could result in delays in seeking care which could exacerbate chronic conditions and/or greater utilization at more costly, hospital-based settings.9

Further, our findings on care for patients with diabetes and mammograms suggest that rural practices may find it challenging to coordinate with ancillary services that happen outside of clinic walls (e.g., imaging, ophthalmologists) because access to other facilities is limited in rural areas. This lack of specialist and facility-based services has likely made rural primary care particularly adept at delivering more comprehensive care (i.e., through more office-based procedures and a broader set of conditions managed) within their clinic walls.17,18,21,36 More comprehensive primary care—where primary care meets the majority of a patient’s physical and common mental health needs17,37,38—likely improves patients’ outcomes overall.16,38 Primary care could use further support developing adequate, robust networks of specialists; policymakers and payers could incentivize virtual networks such as visiting specialist or mobile clinics39 for services that primary care cannot deliver.

In terms of rural primary care, much of the focus by policymakers has been on access to care and care delivery capabilities. Policymakers have worried that small, rural practices will be under-resourced with fewer staff and technology solutions available to coordinate care which may impact their ability to participate in value-based care.19,40 We do not find striking urban-rural disparities in the care delivery capabilities of multi-physician practices. However, we found self-reported participation in payment reform, especially among isolated rural practices in ACO contracts, was lower for rural multi-physician practices. Care delivery capabilities in rural multi-physician practices may be driven, in part, by system ownership. System-ownership typically accelerates practices’ participation in risk-based contracting, but ownership may not be a sufficient motivator for practices in isolated settings given other barriers.29,41 Rural practices may be particularly at risk for acquisition by health systems, especially hospital-based systems,42 as a way to improve financial viability for both the practice and the hospital. The risk for acquisition is likely amplified by the ongoing pandemic with rural practices particularly vulnerable in the face of reduced visit rates and likely with fewer resources to weather-sustained losses.

This study has key limitations. First, we assigned patients to practices based on Medicare billing using outpatient evaluation and management visits as a measure of primary care. Second, this study may not be representative to patients covered by other payers or, especially, those that are uninsured. Medicare policy can have an outsized impact on rural areas because rural populations are aging faster than their urban counterparts.43 Third, our findings on care delivery capabilities were limited to practices with three or more physicians while nearly half of rural primary care practices have a single physician.

Despite challenges in rural primary care related to clinician supply and complex patient populations, our study finds relatively few utilization differences between Medicare patients cared for by rural and non-rural practices. Yet, rural primary care clinicians may be stressed given they deliver care for larger Medicare patient panels, with a dwindling workforce, compared to their urban counterparts. Further, for Medicare patients, there is often considerable travel burden associated with accessing primary care. Policymakers can ease challenges faced by clinicians and patients by ensuring there is a sufficient ongoing rural primary care workforce, by supporting coordination with specialist networks, and by considering sustainable payment strategies to support team-based comprehensive care that can survive without acquisition by larger health systems.

References

Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Donaldson M, Yordy K VN, ed. Institute of Medicine (US ) Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report.

Academy of Family Physicians A. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. Del Med J. 2008;80(1):21-22.

Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(2):166-171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1616

Peikes D, Taylor EF, O’Malley AS, Rich EC. The Changing Landscape Of Primary Care: Effects Of The ACA And Other Efforts Over The Past Decade. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2020;39(3):421-428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01430

Barr MS. The patient-centered medical home: Aligning payment to accelerate construction. Medical Care Research and Review. 2010;67(4):492-499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558710366451

Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(26):2693-2696. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0902909

Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624

Kirch DG, Petelle K. Addressing the physician shortage: The peril of ignoring demography. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;317(19):1947-1948. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.2714

Dall T, West T. 2017 Update The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2015 to 2030 Final Report Association of American Medical Colleges.; 2017.

Chronic Disease in Rural America Introduction - Rural Health Information Hub. Accessed September 18, 2020. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/chronic-disease

Shaw KM, Theis KA, Self-Brown S, Roblin DW, Barker L. Chronic disease disparities by county economic status and metropolitan classification, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2016;13(9):160088. doi:https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.160088

Matthews KA, Croft JB, Liu Y, et al. Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification — United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2017;66(5):1-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6605a1

Rural Data Explorer – Rural Health Information Hub. . https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/data-explorer?id=200

Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2015;13(3).

Peterson LE, Newton WP, Bazemore AW. Working to advance the health of rural Americans: An update from the ABFM. Annals of family medicine. 2020;18(2):184-185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2526

Peterson LE, Fang B. Rural Family Physicians Have a Broader Scope of Practice than Urban Family Physicians.; 2018.

Remarks by Administrator Seema Verma at the National Rural Health Association Annual Conference | CMS. Accessed November 7, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/remarks-administrator-seema-verma-national-rural-health-association-annual-conference

American Medical Association. Proceedings of the 2018 Interim Meeting of the American Medical Association House of Delegates.; 2018.

Peterson LE, Blackburn B, Peabody M, O’Neill TR. Family physicians’ scope of practice and American Board of Family Medicine recertification examination performance. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2015;28(2):265-270. doi:https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140202

NPR. LIFE IN RURAL AMERICA PART II. Published 2019. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://media.npr.org/documents/2019/may/NPR-RWJF-HARVARD_Rural_Poll_Part_2.pdf

NPR. LIFE IN RURAL AMERICA. Published 2018. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2018/10/NPR-RWJF-Harvard-Rural-Poll-Report_FINAL_10-15-18_-FINAL-updated1130.pdf

Cohen GR, Jones DJ, Heeringa J, et al. Leveraging diverse data sources to identify and describe U.S. health care delivery systems. eGEMs. 2017;5(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/egems.200

About NSHOS – Comparative Health System Performance. Accessed April 8, 2020. https://sites.dartmouth.edu/coe/nshos/

Fraze TK, Brewster AL, Lewis VA, Beidler LB, Murray GF, Colla CH. Prevalence of screening for food insecurity, housing instability, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence by US physician practices and hospitals. JAMA network open. 2019;2(9):e1911514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11514

Ouayogodé MH, Fraze T, Rich EC, Colla CH. Association of Organizational Factors and Physician Practices’ Participation in Alternative Payment Models. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(4):e202019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2019

Fraze TK, Beidler LB, Briggs ADM, Colla CH. Eyes in the home: ACOs use home visits to improve care management, identify needs, and reduce hospital use. Health Affairs. 2019;38(6):1021-1027. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00003

Fisher ES, Shortell SM, O’Malley AJ, et al. Financial integration’s impact on care delivery and payment reforms: A survey of hospitals and physician practices. Health Affairs. 2020;39(8):1302-1311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01813

Left Out: Barriers to Health Equity for Rural and Underserved Communities.; 2020.

Katzman JG, Galloway K, Olivas C, et al. Expanding health care access through education: Dissemination and implementation of the ECHO model. Military Medicine. 2016;181(3):227-235. doi:https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00044

MACPAC. Access in Brief: Rural and Urban Health Care.; 2018.

Fraze TK, Briggs ADM, Whitcomb EK, Peck KA, Meara E. Role of nurse practitioners in caring for patients with complex health needs. Medical Care. 2020;58(10):853-860. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001364

Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):908-914.

Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an Aging Rural Physician Workforce. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(4):299-301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1900808

Liaw WR, Jetty A, Petterson SM, Peterson LE, Bazemore AW. Solo and small practices: A vital, diverse part of primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2016;14(1):8-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1839

O’Malley AS, Rich EC. Measuring comprehensiveness of primary care: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(3):568-575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3300-z

O’Malley AS, Rich EC, Shang L, et al. New approaches to measuring the comprehensiveness of primary care physicians. Health Services Research. 2019;54(2):356-366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13101

Gruca TS, Pyo TH, Nelson GC. Providing Cardiology Care in Rural Areas Through Visiting Consultant Clinics. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5(7). doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002909

Putting our Rethinking Rural Health Strategy into Action | CMS. Accessed July 2, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/blog/putting-our-rethinking-rural-health-strategy-action

Edwards ST, Marino M, Solberg LI, et al. Cultural And Structural Features Of Zero-Burnout Primary Care Practices. 2021;40(6):928-936. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/HLTHAFF.2020.02391

Rates of Hospital Acquisition of Physician Practices Have Accelerated Dramatically in Rural Areas. . https://avalere.com/insights/rates-of-hospital-acquisition-of-physician-practices-have-accelerated-dramatically-in-rural-areas

Bureau UC. Older Population in Rural America.

Acknowledgements

The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from IQVIA information services (OneKey subscription information services 2010–2017, IQVIA Inc., all rights reserved).

Funding

This work was supported by AHRQ’s Comparative Health System Performance Initiative under Grant no. 1U19HS024075, which studies how health care delivery systems promote evidence-based practices and patient-centered outcomes research in delivering care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IQVIA Inc. or AHRQ or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 271 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fraze, T.K., Lewis, V.A., Wood, A. et al. Configuration and Delivery of Primary Care in Rural and Urban Settings. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 3045–3053 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07472-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07472-x