ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Enhancing patient-centered care and shared decision making (SDM) has become a national priority as a means of engaging patients in their care, improving treatment adherence, and enhancing health outcomes. Relatively little is known about the healthcare experiences or shared decision making among racial/ethnic minorities who also identify as being LGBT. The purpose of this paper is to understand how race, sexual orientation and gender identity can simultaneously influence SDM among African-American LGBT persons, and to propose a model of SDM between such patients and their healthcare providers.

METHODS

We reviewed key constructs necessary for understanding SDM among African-American LGBT persons, which guided our systematic literature review. Eligible studies for the review included English-language studies of adults (≥ 19 y/o) in North America, with a focus on LGBT persons who were African-American/black (i.e., > 50 % of the study population) or included sub-analyses by sexual orientation/gender identity and race. We searched PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, PsycINFO, and Scopus databases using MESH terms and keywords related to shared decision making, communication quality (e.g., trust, bias), African-Americans, and LGBT persons. Additional references were identified by manual reviews of peer-reviewed journals’ tables of contents and key papers’ references.

RESULTS

We identified 2298 abstracts, three of which met the inclusion criteria. Of the included studies, one was cross-sectional and two were qualitative; one study involved transgender women (91 % minorities, 65 % of whom were African-Americans), and two involved African-American men who have sex with men (MSM). All of the studies focused on HIV infection. Sexual orientation and gender identity were patient-reported factors that negatively impacted patient/provider relationships and SDM. Engaging in SDM helped some patients overcome normative beliefs about clinical encounters. In this paper, we present a conceptual model for understanding SDM in African-American LGBT persons, wherein multiple systems of social stratification (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation) influence patient and provider perceptions, behaviors, and shared decision making.

DISCUSSION

Few studies exist that explore SDM among African-American LGBT persons, and no interventions were identified in our systematic review. Thus, we are unable to draw conclusions about the effect size of SDM among this population on health outcomes. Qualitative work suggests that race, sexual orientation and gender work collectively to enhance perceptions of discrimination and decrease SDM among African-American LGBT persons. More research is needed to obtain a comprehensive understanding of shared decision making and subsequent health outcomes among African-Americans along the entire spectrum of gender and sexual orientation.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The 2011 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report ‘The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for a Better Understanding’ describes how LGBT persons are often marginalized within medical settings and at increased risk for health disparities.1 Understanding how to promote patient-centered care and shared decision making (SDM), in general and among LGBT populations, has become a national priority.2–6 The IOM, American Medical Association (AMA), American College of Physicians (ACP) and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) have all endorsed shared decision making between patients and physicians.3–6 In 2015, the ACP published a position paper on LGBT health disparities that called for increased physician understanding of how to provide patient-centered care for LGBT persons that addresses both environmental and social factors impacting mental and physical health.7

Despite the increasing priority of both shared decision making and LGBT health within the medical community, there has been little attention paid to “dual minorities”—LGBT persons who are also racial/ethnic minorities8,9—despite their significantly increased risk for social disadvantage and poor health outcomes.10–13 Race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender each represents a heterogeneous group of social identities (Table 1) that can interact within individual persons to magnify their risk for discrimination and poor health.14,15

In this paper, we review key constructs necessary for understanding shared decision making among African-American LGBT persons, which guided our systematic literature review of SDM in this population. Together, these informed (and were informed by) the development of our conceptual model for understanding SDM in African-American LGBT persons. We report on the findings of our systematic review, present our conceptual model, and illuminate future research SDM directions for populations at the intersection of race and sexual orientation/gender.

Shared Decision making and Patient-Centered Care

Shared decision making, where patients and clinicians work collaboratively to identify treatment plans that meet patients’ needs and preferences, is currently conceptualized as having three key domains: information-sharing between patients and providers, deliberation about the pros and cons of treatment choices, and decision making about a treatment plan that is endorsed by both the patient and the clinician.16–20 Shared decision making, and patient/provider communication, has been associated with a number of positive health outcomes, including control of diabetes and hypertension, adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy, improved mental health and well-being, and patient satisfaction.21–26

Disparities in communication and shared decision making are well-documented among racial/ethnic minorities, particularly African-Americans,27–31 and there is growing research suggesting similar disparities among sexual and gender minority populations.32,33 These differences in patient/physician communication may be an important contributor to existing health disparities among marginalized populations.13,34 For African-Americans as well as LGBT persons, there is evidence that providers’ unconscious racial and/or heterosexual biases can influence medical care and their expectations for patient adherence and SDM engagement.32–36 For example, one study revealed how physician perceptions about African-American men’s likelihood of adherence to highly actively antiretroviral therapy (HAART) influenced treatment recommendations, including the prescription rates for medications to prevent opportunistic infections.36

LGBT persons, in general, may have identity-specific healthcare issues that put them at higher risk for poor health, and for which patient-centered care and shared decision making may improve health outcomes. For example, there is evidence that transgender women may prioritize transition-related care, particularly hormone treatment, more so than primary care or HIV-related care,37 and have fear of discriminatory treatment in the healthcare setting.38,39 The utilization of self-administered hormones (purchased from street markets) in unsafe doses39 by transgender women could potentially be reduced by culturally tailored medical care that involves a shared approach to identifying health priorities and choosing treatment plans.32

While there is growing literature about patient/provider relationships and SDM among racial/ethnic minorities and LGBT persons, little is known about these issues among populations that live at the intersection of such identities, such as African-American LGBT persons. Understanding how race, sexual orientation and gender identity can simultaneously influence shared decision making is an important step in addressing health disparities among such ‘dual minority’ populations.

Applying Intersectionality to Health Disparities

Health disparities research often focuses on a single social group (e.g., African-Americans, elderly populations, immigrants) while adjusting for other sociodemographic characteristics, rather than considering the interactive effects of multiple social identities. This can result in an incomplete understanding of how the cumulative lived experience of individuals contributes to health disparities, and accounts for some of the within-group variation noted among minority groups.40–42

‘Intersectionality’ is the study of how multiple systems of social stratification (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation) influence an individuals’ identity and lived experience, recognizing that every person holds a position (privilege or disadvantage) in different systems simultaneously, and that such positions can vary in magnitude and direction depending on time, place, and circumstance.43–46 For example, an African-American bisexual man may inhabit a different social position as a part of a community coalition to address HIV than while at work in the police department. Intersectionality also explores how different levels of a social framework influence individuals experiences, including the intrapersonal level (e.g., internalized racism),47 the interpersonal level (e.g., bias, discrimination),48 the contextual level (e.g., societal victimization such as hate crimes),49 and the macro-level, where structural inequalities (e.g., education, income distribution) exist.12

Intersectionality highlights how persons with multiple disadvantages can have interactive effects on their health and well-being. For example, multiply disadvantaged persons are more likely to report interpersonal discrimination (conscious behavioral bias), microaggressions (unconscious behavioral bias), psychological distress, worse self-rated health, and more functional limitations than their singly disadvantaged or privileged counterparts.10,11,50–53 African-American LGBT persons can be disadvantaged within multiple social systems, based on race, sexual orientation and/or gender.54–59 This multiple disadvantage may compel such persons to maintain several separate identities, in which they de-emphasize or conceal aspects of themselves in different communities as a coping mechanism to marginalization.12,14,59,60 For example, “code-switching” (behavioral adaptations to fit specific contexts)61 has been used by African-American bisexual men to avoid discrimination within the African-American heterosexual community.15,62 However, research suggests that having an integrated identify among African-American LGBT persons may be associated with higher levels of well-being and health promoting behaviors (e.g., higher self-esteem and life satisfaction, less internalized conflict and psychological distress, higher HIV prevention self-efficacy).14 Such persons who straddle separate groups, on the other hand, may have structural advantages as ‘brokers’ who can help diffuse behavioral changes and treatment innovations.63

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify articles on shared decision making (SDM) in the African-American LGBT population. PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched. The search strategy included MESH terms and keywords based on the following concepts: shared decision making (e.g., patient/provider communication, patient/provider relationship, shared decision making, participatory decision making, patient-centered communication, treatment decisions, decision aid, and patient empowerment, African-Americans (e.g., African-Americans, Blacks, minorities), LGBT persons (e.g., homosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, men who have sex with men, and transgender persons) (see Online Appendix 1). We also included MeSH terms and key words for concepts that were related to communication quality among minority populations such as trust, physician bias, and discrimination. Additional references were identified by hand searching relevant articles’ reference lists and the Table of Contents of key peer-reviewed journals.

We included studies written in English and did not limit studies based on the date of publication. We included all types of completed studies (i.e., qualitative studies, cross-sectional studies, observational studies, and clinical trials) that were conducted in North America (United States and/or Canada), included human (i.e., patient and/or physician) data, and included adults only (19 years old and above). We included studies that focused on LGBT persons who were African-American/black (i.e., >50 % of the study population) or included sub-analyses by sexual orientation/gender identity and race. We excluded studies on prevalence of behaviors (e.g., sexual practices, lifestyle behaviors) if there was no explicit relationship to patient/provider communication or SDM.

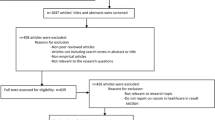

The results of the searches were combined and duplicates were removed. This process identified 2298 abstracts, which were independently reviewed by five of the co-authors to determine eligibility for study inclusion; disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data were abstracted from full text articles using an adapted abstraction form from Zaza and colleagues.64 Thirty-eight studies were eligible for full text review; these were independently reviewed by the co-authors and discussed as a group. Ultimately, three studies met the inclusion criteria and an additional three were ‘near-misses’ that we include here to illustrate important issues in African-American LGBT SDM (Online Appendix 2). This systematic review adhered as closely as possible to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA).65

Results

Included Studies (Table 2)

Three studies met the systematic review’s criteria. One was a cross-sectional study and two were qualitative studies, one of which included a conceptual model of interaction between patients, providers and setting for African-American MSM. One study involved transgender women (91 % minorities, 65 % of whom were African-Americans), and two involved African-American men who have sex with men (MSM). Sevelius et al. reported on antiretroviral adherence and healthcare experiences of transgender women and those of other HIV positive study participants.32 The study utilized an instrument to measure the quality of patient/provider interactions, which included items such as ‘feeling helped’ by the provider, receiving assistance with medication management (e.g., side effects), and feeling that the patient and provider had agreed on a treatment plan that the patient could follow (i.e., shared decision making). Transgender women reported significantly fewer positive interactions with their providers than non-transgender participants.32

Wheeler conducted a qualitative study of African-American men who have sex with men (MSM) to understand the role of the patient/provider relationship in HIV/AIDS management.66 He found that patients in the study reported that the patient/provider relationship impacted health beliefs (e.g., those with a collaborative [or ‘shared’] style were able to overcome patient normative beliefs that health encounters were traumatic occurrences) and medication adherence (e.g., clinicians were as a trusted source of information).66 Because many participants had not disclosed their sexual orientation to those in their personal lives, the ability to do so with physicians placed a greater ‘premium’ on the patient/provider relationship. The ability to communicate in an open, honest manner, and to identify and respond to sociocultural cues about sexual orientation were reported as important facilitators of the patient/provider relationship.66 Wheeler also presented a sociocultural model to describe the relationships between sociodemographic variables and health outcomes among African-American MSM.66

Malebranche et al. conducted a qualitative study of African-American MSM to understand the social issues that influence barriers to medical care, communication with providers, and treatment adherence.15 The experiences of societal discrimination due to race (perceived as the dominant source of discrimination) and sexual orientation (particularly within the African-American community) were ones that: 1.) precipitated feelings of social isolation in both the mainstream gay community and the African-American community, 2.) promoted the development of a dual identity and ‘code-switching’ as a coping mechanism, and 3.) influenced expectations of providers within medical settings.15 Perceived discrimination, fear, and mistrust of healthcare systems fostered feelings of detachment from medical experiences, and served as barriers to provider communication and treatment adherence.12 The quality of verbal communication was perceived as an important part of the patient/provider relationship and overall healthcare experience; it influenced the choice of clinic and satisfaction with care.15

Illustrative Examples (Table 3)

Several studies involved African-Americans and sexual minorities, but were excluded because these represented only a small subset of the study population, information on the intersectionality of participants was not included (e.g., race and sexual orientation demographics were analyzed separately), or because the nature of the study was about patient/provider relationships in general, and not specific to SDM. We discuss their themes briefly here because of their general salience to the systematic review. These studies found patient-reported disparities in communication (i.e., end-of-life care among patients with advanced AIDS) among racial/ethnic minorities (African-Americans and Latinos) and gay/bisexual men,67 and fears of healthcare discrimination among transgender women of color that led to delays in seeking medical services.68 Better physician/patient relationships, including higher measures of communication (general communication, HIV-specific information sharing, participatory decision making, and adherence dialogue), were positively associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy.20

CONCEPTUAL MODEL

The development of our model draws upon prior research and model development in two areas: shared decision making among African-Americans with diabetes19,69–71 and intersectionality among multiply disadvantaged groups.14,45,72–77 We also confirmed our conceptual model’s core constructs using the studies described in our systematic review.

The Environment

In our model, ‘the environment’ represents both physical (e.g., location, infrastructure, resources) and social (e.g., cultural, political) context in which people live, which shape their experiences and expectations, including service quality in health systems and interactions with physicians. We categorized the environment according to scope (society, community, and clinic), illustrated by concentric rings framing the SDM process. Society refers broadly to the structural and social systems within the U.S. (e.g., healthcare, housing), in which there exist pervasive inequities based on social position. The U.S. social system contains structural and social inequalities embedded in its normal operation. Although these inequalities are listed are “society”, they are pervasive throughout every level of the environment though potentially in different forms. Communities can be formed around multiple commonalities (e.g., religion, cultural practices) or identities (e.g., race, sexual orientation), and can transcend physical location (e.g., virtual communities). Clinic refers to the medical care setting in which the patient/physician encounter occurs. Clinic characteristics (e.g., ‘free’ clinic vs. private practice, affiliation with a medical school, primary care vs. subspecialty clinic [e.g., HIV/AIDS, oncology]) and geographic location may influence patient expectations about their quality of medical care, and affect their SDM self-efficacy.

Figure 1 offers a visual representation of an individual’s multiple axes of identity in separate systems of social stratification.72 Each axis is depicted as a ring that simultaneously intersects and interacts with every other axis.45 The mirror represents how a person has internalized his/her social identities (e.g., an integrated identity vs. compartmentalized identities) and perceives him/herself in the world, as informed by his/her lived experiences.14,45,74 Thus, the mirror also represents the influence of society’s attitudes on an individual’s self-perception.

Figure 2 illustrates how patients and providers perceive each other, based on their known or assumed roles and social identities. All perception is influenced by generalized and oversimplified ideas (stereotypes) and preferences (prejudices) that affect people’s attitudes, actions, decisions and understandings of others (implicit biases).75–77 Figure 2 depicts how patients and providers, given their lived experiences, bring their own expectations of one another to the clinical encounter, which can affect patient/provider communication and behaviors. Figure 2 also illustrates the influence of society’s expectations about how patients and physicians should behave given their roles and social identities. These societal beliefs may affect the way patients and providers perceive and communicate with each other during the clinical encounter.

Figure 3 builds upon Peek et al.’s conceptual model of how race as a social identity impacts shared decision making, behaviors and health outcomes.71 We expand this model to include multiple other social identities (e.g., gender, sexual orientation) and how these identities intersect with each other.

In Peek’s model, the ability for patients and physicians to engage in shared decision making with each other is determined by their individual decision making preferences, trust in each other, and the existing patient/physician relationship. We have added arrows to show the important interactions between preferences, trust and the patient/physician relationship in shaping the SDM experience. In Peek’s model, self-efficacy, understanding, trust and satisfaction are downstream patient outcomes that mediate patient self-management behaviors and subsequent health outcomes. In our conceptual model, we have expanded these downstream effects to include physician outcomes (e.g., increased job satisfaction, increased physician self-efficacy and understanding in caring for patients who are racial, sexual and/or gender minorities) that improve care delivery to the patient population and contribute to improved patient health outcomes.

While we represent the conceptual model in three different figures (described above), it is important to note the inter-relationships and bidirectional influences between each figure, especially how social identity (Fig. 1) and perceptions of others (Fig. 2) can directly influence shared decision making (Fig. 3). Figure 4 combines all three figures into a single image to underscore these complex inter-relationships. For example, in response to perceptions or expectations of racism or heterosexism by physicians (Fig. 2), patients may withhold information (e.g., sexual orientation and sexual practices) or alter their behaviors (e.g., “code-switching” by African-Americans to adopt a more deferential tone to white physicians) in attempt to influence provider perceptions and ensure a higher quality medical care. Such “impression management” behaviors are commonly utilized strategies among marginalized populations, and can impact the patient/physician relationship and SDM.15,61,62

DISCUSSION

This paper underscores the importance of helping physicians to understand the multiple, intersecting social identities that African-American LGBT persons have and how these intersections shape lived experiences. These experiences are complex and not easily made explicit within a SDM context. African-American LGBT persons are thus at potential increased risk for discrimination, marginalization, and worse mental and physical health outcomes. African-American LGBT persons may live in a compartmentalized (vs. integrated) manner, which also may contribute to worse mental and physical health outcomes. Thus, creating a safe space for African-Americans who are LGBT to engage all dimensions of their identities may facilitate better patient/provider relationships, communication, and treatment adherence among this population—all necessary components of SDM.

In this paper, we also describe a conceptual model, informed by previous work,14,19,45,69–77 that demonstrates how social identity, perceptions of social identity, and structural inequities all inform shared decision making between patients and physicians. Expectations for, and the interpretation of, clinical encounters are often influenced by past experiences and normative beliefs about physicians and healthcare delivery.12 For example, prior experiences with discrimination, based upon racialized encounters, may influence how willing patients may be to fully disclose sexual orientation for fear of additional discrimination.

Shared decision making, in its original conceptualization, assumes that all patients can understand the options available to them (if properly informed) and have similar self-efficacy and skills in choosing and implementing treatment plans.16,17 However, persistent structural inequities and social advantage/disadvantage promote learned helplessness78 and entitlement/privilege79 among populations in ways that encourage some patients to believe they have fewer options and lower self-efficacy, and encourage others to believe they have more options and higher self-efficacy, regardless of the external realities. Structural inequality affects not only the material realities (e.g., proportion of goods and services available) of a person’s life, but also the internal beliefs and expectations that may obscure perceptions of those material realities. That is, persons with multiple social disadvantages may not only have less access to medical care and limited treatment options given to them, but they may also perceive that they have even fewer options than they actually do. Thus, fully engaging African-American LGBT persons in shared decision making requires that physicians and health systems work to create equal, trusting relationships with patients and also ensure equal access to treatment options and medical care.13,69,80–82

It is important to note that both physicians and patients are impacted by the relative privilege and disadvantage associated with multiple systems of social stratification. The healthcare setting is a structural system in which there is a hierarchy of power/advantage based on roles (e.g., physician vs. clerical staff, physician vs. patient) as well as social identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation). Thus, the power dynamics between physicians and patients are not the same in every patient/provider relationship. Future research should explore how physicians who are African-American LGBT persons may impact SDM with patients of similar and different identities.

Our systematic review identified only six relevant studies to better understanding SDM among African-American LGBT persons, which reflects the general paucity of literature about the health of persons at the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation/gender identity. All of the studies focused on HIV infection and none dealt with African-American women who were sexual minorities or African-American transgender men. While research indicates that decision-aids can improve shared decision making among racial/ethnic minorities,83 none of our studies identified clinical tools such as decision aids to assist in SDM among African-American LGBT persons. And although concerns about healthcare discrimination and other organizational factors (e.g., loss of privacy) were noted themes, we did not find any organizational or clinician interventions to improve SDM among this population. This is particularly concerning given the array of clinical contextual factors that can be leveraged to support SDM.84 Thus, much more research is needed to obtain a comprehensive understanding of shared decision making among African-Americans along the entire spectrum of gender and sexual orientation, and how patients’ intersectionality can influence physician perceptions and behaviors, the patient/physician relationship, and shared decision making within the clinical encounter.

This paper focused on the synergistic negativity that multiple minority statuses may engender. Less is known about how having an African-American LGBT status can lead to social advantages, and subsequently improved health outcomes. Dual statuses are common among those who are “bridges” or brokers within their social networks.63 Such persons may have access to information that is helpful to both physicians (e.g., normative cultural beliefs, patient populations) and patients (e.g., new medical treatments) that make them effective change agents and bridges between health systems and marginalized populations.85 Additional research is needed to better understand how African-American LGBT persons, and other ‘dual minorities,’ can be leveraged to improve health behaviors, physician skills, shared decision making, and health outcomes among these populations.

REFERENCES

Institute of Medicine. Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities; Board on Health of Select Populations. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/The-Health-of-Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-People.aspx. Accessed January 20, 2016.

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ). The SHARE Approach. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html Accessed January 20, 2016.

American College of Physicians. American College of Physicians endorses shared decision making approach for prostate cancer screening. 2013. http://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/2013/04/09/american-college-of-physicians-endorses-shared-decision making-approach-for-prostate-cancer-screening/. Accessed January 20, 2016.

American Medical Association. Getting the most for our health care dollars: Shared decision making. Available at: http://www.allhealth.org/briefingmaterials/AMASharedDecisionMaking-1936.pdf Accessed January 20, 2016.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. 2011. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/186750/data/core_competencies.pdf . Accessed January 20, 2016.

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Daniel H, Butkus R. Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Disparities: Executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M14-2482. Published online 12 May 2015.

Makadon H, Mayer K, Potter J, Goldhammer H, eds. The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2008.

Deblaere C, Brewster ME, Sarkees A, Moradi B. Conducting research with LGB people of color: Methodological challenges and strategies. Couns Psychol. 2010;38:331–62.

Gayman M, Barragan J. Multiple perceived reasons for major discrimination and depression. Soc Ment Health. 2013;3:203–20.

Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1869–76.

Seng JS, Lopez WD, Sperlich M, Hamama L, Reed Meldrum CD. Marginalized identities, discrimination burden, and mental health: empirical exploration of an interpersonal-level approach to modeling intersectionality. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2437–45.

Smedley BD, Stith SY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. Institute of Medicine; 2002.

Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, Soto T. The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. J Sex Res. 2002;39:179–89.

Malebranche DJ, Peterson JL, Fullilove RE, Stackhouse RW. Race and sexual identity: perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:97–107.

Charles C, Gafini A, Whelan T. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–92.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–61.

Montori VM, Gafni M, Charles C. A shared treatment decision making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9:25–36.

Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Wilson SC, Chin MH. How is Shared Decision making Defined among African-Americans with Diabetes? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:450–458.

Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1096–103.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Practice. 2000;49:796–804.

Adams RJ, Smith BJ, Ruffin RE. Impact of the physician’s participatory style in asthma outcomes and patient satisfaction. Ann Allerg Asthma Im. 2001;86:263–71.

Rabkin JG, Remien RH, Wilson C. Good doctors, good patients: Partners in HIV Treatment. New York: NCM Publishers; 1994.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–57.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–8.

Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–33.

Wallace LS, DeVoe JE, Rogers ES, Malagon-Rogers M, Fryer GE Jr. The medical dialogue: Disentangling differences between hispanic and non-hispanic whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1538–43.

Cooper-Patrick LA, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583–9.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–15.

Levinson W, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, Frankel RM, Kuby A, Bereknyei S, et al. “It’s not what you say.”: racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008;46:410–6.

Ratanawongsa N, Zikmund-Fisher B, Couper MP, Van Hoewyk J, Powe NR. Race, ethnicity, and shared decision making for hyperlipidemia and hypertension treatment: The DECISIONS survey. Med Decision Making. 2010;30:65S–76S.

Sevelius JM, Carrico A, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:256–64.

Gerbert B, Maguire BT, Bleecker T, Coates TJ, McPhee SJ. Primary care physicians and AIDS: Altitudinal and structural barriers to care. JAMA. 1991;266:2837–42.

van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved With Good Intentions: Do Public Health and Human Service Providers Contribute to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:248–55.

Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status(SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:554–63.

Siegel K, Karus D, Schrimshaw EW. Racial differences in attitudes toward protease inhibitors among older HIV-infected men. AIDS Care. 2000;12:423–34.

Kammerer N, Mason T, Connors M, Durkee R. Transgender health and social service needs in the context of HIV risk. In: Bockting W, Kirk S, eds. Transgender and HIV: Risks, prevention and care. Binghamton, NY: Haworth; 2001:39–57.

Lombardi E. Public health and trans-people: Barriers to care and strategies to improve treatment. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, eds. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspective on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. New York, NY: Springer; 2007:638–52.

Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:713–9.

Williams DR, Kontos EZ, Viswanath K, Haas JS, Lathan CS, MacConaill LE, Chen J, Ayanian JZ. Integrating multiple social statuses in health disparities research: the case of lung cancer. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:1255–77.

Ailshire JA, House JS. The Unequal Burden of Weight Gain: An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Social Disparities in BMI Trajectories from 1986 to 2001/2002. Soc Forces. 2011;90:397–423.

Erving CL. Gender and physical health: a study of African-American and Caribbean black adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52:383–99.

Bowleg L. When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–25.

Purdie-Vaughns V, Eibach R. Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles. 2008;59:377–91.

Jones SR, McEwen MK. A conceptual model of multiple dimensions of identity. J College Stud Dvpmt. 2000;41:405–14.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73.

Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:318–31.

Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:208–30.

Klest B. Childhood Trauma, Poverty and adult victimization. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:245–251.

Microaggressions in everyday life: Race gender and sexual orientation. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley &Sons, Inc; 2010.

Grollman EA. Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: the role of multiple forms of discrimination. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55:3–19.

Grollman EA. Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53:199–214.

Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:368–79.

Adams CL, Kimmel DC. Exploring the lives of older African-American Gay Men. In: Green B, ed. Ethnic and cultural diversity among lesbian and gay men. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc; 1997:132–151.

Greene B. Ethnic-minority lesbians and gay men: Mental health and treatment issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:243–51.

Greene B. Ethnic-minority lesbians and gay men: Mental health and treatment issues. In: Greene B, ed. Ethnic and cultural diversity among lesbians and gay men: Psychological perpectives on lesbian and gay issues. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc; 1997:216–39.

Herek GM, Capitanio J. Black heterosexuals’ attitudes towards lesbians and gay men in the United States. J Sex Res. 1995;32:95–105.

Icard L. Black gay men and conflicting social identities: Sexual orientation versus racial identity. J Soc Work Hum Sex. 1986;4:83–93.

Michael RT, Gagnon JH, Laumann EO, Kolata G. Sex in America: A definitive survey. Little, Brown, & Company: Boston (MA); 1994.

Dubé EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:1389–98.

Molinsky AL. Cross-cultural code-switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Acad Manage Rev. 2007;32:622–40.

Garner GL. Managing Heterosexism and Biphobia: A Revealing Black Bisexual Male Perspective. Ann Arbor (MI): ProQuest; 2008.

Burt RS. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2005.

Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1S):44–74.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9.

Wheeler DP. Working with positive men: HIV prevention with black men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(1 Suppl A):102–15.

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Greenlee H, Collier AC. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS. 1999;13:1123–31.

Bith-Melander P, Sheoran B, Sheth L, Bermudez C, Drone J, Wood W, Schroeder K. Understanding sociocultural and psychological factors affecting transgender people of color in San Francisco. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:207–20.

Peek ME, Wilson SC, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn MT, Odoms-Young A, Chin MH. Barriers and facilitators to Shared Decision making among African-Americans with Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1135–9.

Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Race and Shared Decision making: Perspectives of African-American Patients with Diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1–9.

Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Racism in healthcare: Its relationship to shared decision making and health disparities: A response to Bradby. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:13–17.

Schultz A, Mullings L. Gender, Race, Class and Health: Intersectional Approaches. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2006.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73.

Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–15.

Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1464–80.

Hamilton DL, ed. Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981.

Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit Bias among Physicians and its Prediction of Thrombolysis Decisions for Black and White Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–8.

Heslin PA, Bell MP, Fletcher PO. The devil without and within: A conceptual model of social cognitive processes whereby discrimination leads stigmatized minorities to become discouraged workers. J Organ Behav. 2012;33:840–862.

Kimmel M, Ferber A. Privilege: A reader. Boulder (CO): Westview Press; 2013.

Smith DB. Addressing racial inequities in health care: civil rights monitoring and report cards. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1998;23:75–105.

Wheeler DP. Strategies for evaluating our AIDS organizations and programs: How can we serve our people better? In: Grant L, Stewart P, Lynch V, eds. Social workers address the HIV/AIDS crisis: Voices from and to the African-American family. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1998:99–117.

Peek ME, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn MT, Young AO, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Trust and shared decision making among African-Americans with diabetes. Health Commun. 2013;28:616–23.

Nathan AG, Marshall IM, Cooper JM, Huang ES. Use of decision aids with minority patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3609-2.

DeMeester RH, Lopez FY, Moore JE, Cook SC, Chin MH. A model of organizational context and shared decision making: application to LGBT racial and ethnic minority patients. J Gen Intern Med. forthcoming.

Schneider JA, Zhou AN, Laumann EO. A new HIV prevention network approach: Sociometric peer change agent selection. Soc Sci Med. 2015;125:192–202.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1U18 HS023050) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program. Dr. Peek was also supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949). Dr. Schneider was also supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01DA033875). Some of the paper’s content was presented as a workshop at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, 23 April 2015. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of University of Chicago librarians Debra A. Werner and Ricardo Andrade in conducting the literature review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Financial Support

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1U18 HS023050) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program. Dr. Peek was also supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949). Some of the paper's content was presented as a workshop at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, April 23, 2015.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peek, M.E., Lopez, F.Y., Williams, H.S. et al. Development of a Conceptual Framework for Understanding Shared Decision making Among African-American LGBT Patients and their Clinicians. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 677–687 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3616-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3616-3