Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the validity, reliability, and optimal cut-off points for the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Well-being Index (WHO-5) to screen mild depression among 400 Iranian students who completed these tools and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-13). Further, a psychiatrist diagnosed the depression by using the “Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.” The validity and internal consistency of tools assessed and the accuracy were computed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC). The internal consistency values of PHQ-2, PHQ-9, and WHO-5 were .73, .88, and .94, respectively. The PHQ-2 (.53), PHQ-9 (.60), and WHO-5 (.54) were significantly associated with the BDI. The PHQ-2, PHQ-9, and WHO-5 had optimal cut-off points of 2, 5, and 9 with an AUC of .809, .851, and .823, respectively. Based on these findings, it is recommended to use the PHQ-9 for mild depression screening among medical university students in Iran because of its high sensitivity and specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Depression is a serious public health problem and common mental disorder that adversely affects the quality of life (Klemanski et al. 2017; Paus et al. 2008). A meta-analysis study indicated that the prevalence of depression among Iranian students was high in comparative to the public people living in Iran (Sarokhani et al. 2013). Their results indicated that the prevalence of depression in Iranian students was 33% (CI 95%: 32–34). Depression increased risk of substance abuse, suicide attempts, sleep disturbance, lack of self-care, poor concentration, anxiety, and lack of interest in everyday experiences (Ibrahim et al. 2013). The cost of affective disorders can be particularly high in young people since they represent the future of any community, its hope, and potential leaders (Ibrahim et al. 2013).

Undergraduate students, who are in transition from adolescence to youth, must successfully complete heavy courses and upgrade their resumes in order to find a suitable job in a competitive environment. Therefore, they are more prone to a variety of mental health problems such as depression (Lei et al. 2016; Nezam et al. 2020). Due to the lack of healthcare providers in the universities and their limited access to the diagnostic resources such as psychiatrists and psychologists, the problems cannot be detected, its severity may increase, and it may become a chronic depression (Farabaugh et al. 2019; Hill et al. 2015). The use of highly sensitive and specific screening tools can reduce the workload of healthcare providers and allow them to spend more time with people having depression (Hill et al. 2015).

Screening is a solution to improve depression care (Gilbody et al. 2008; Thombs et al. 2012). Among the variety of tools for screening depression, there is a need for a brief and valid tool that can diagnose depression and its severity (Ferreira et al. 2019). The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), its ultra-brief version (PHQ-2), and Well-being Index (WHO-5) are among the briefest and widely used instruments that are translated to many languages and validated in various settings (Wu 2014). Based on the initial validation studies, there were recommended certain structures and also cut-off scores for each instrument. Recent studies performed in different settings revealed that cut-off scores for these instruments cannot be generalized (Manea et al. 2012). For this reason, there is a need to validate and find the best cut-off scores for each instrument (Beard et al. 2016; Kohrt et al. 2016; Smith Fawzi et al. 2019). Accordingly, we investigated the validity, reliability, and optimal cut-off points of the PHQ-2, PHQ-9, and WHO-5 to screen mild depression among Iranian medical university students.

Method

Sample

The study included 400 undergraduate students from Tehran, Iran, Mazandaran, and Kashan medical universities. The adequate sample size for the cut-off point studies was recommended as 250 (Manea et al. 2012). This study was conducted with approval from the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Purpose of the study was explained to the participants, and informed consent forms were obtained from each participant. Detailed sample characteristics were provided in the results section.

Procedure

The participants completed the self-administered PHQ-9, PHQ-2, WHO-5, and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-13), and also a psychiatrist (having a 15-year experience in diagnostic) conducted interviews to determine each students’ depression level (for 7 weeks). Hardcopy questionnaires were fulfilled, and face to face interviews were conducted in the classrooms and libraries.

Instruments

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a nine-item scale that was developed and validated as a depression screening tool for the primary care and non-psychiatric settings (Kroenke and Spitzer 2002; Liu et al. 2011; Zuithoff et al. 2010). It can be used faster than the BDI thanks to its brevity and ease of scoring. Each question rated from 0 to 3 (0, not at all; 1, several days; 2, more than half of all the days; 3, nearly every day), and results range from 0 to 27, with 27 indicating the greatest severity of the depressive symptoms. The optimal cut-off score of the PHQ-9 can be different for patients and general community and also for screening and diagnosis purposes (Kendrick et al. 2009; Kroenke et al. 2010). The PHQ-9 was previously translated and validated in Iran for patients (Dadfar et al. 2018a; Khamseh et al. 2011; Omani-Samani et al. 2018); however, it has not been validated for university students.

Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) includes the first two items of the PHQ-9 and usually used as the initial depression screening instrument for the major depressive disorder (MDD). Results range from 0 to 6, with 6 indicating the greatest severity of the depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the accuracy of PHQ-2 examined in different studies (Dadfar et al. 2019; Jafari et al. 2014).

WHO-5 Well-being Index is a widely used tool for depression screening consisting five items rated on a 6-point Likert as follows: at no time (0), some of the time (1), less than half of the time (2), more than half of the time (3), most of the time (4), and all of the time (5). The responses are from 0 (worst well-being) to 100 (best well-being). Validity of the WHO-5 was verified among Iranian outpatients (Dadfar et al. 2018b).

BDI-13 is developed to assess the severity of depression. It has 13 items that are rated on a four-point Likert scale from “0” to “3” in terms of intensity, and results range from 0 to 39, with 39 indicating the greatest severity of the depressive symptoms. BDI-13 has been validated and is widely used in Iran (Dadfar and Kalibatseva 2016).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 19, STATA, and AMOS were used for statistical analysis of the study. The characteristics of participants and mean score of depression for each tool are determined. Normality of distribution was checked by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Further, independent t test and non-parametric Mann-Whitney test were used to compare mean score of depression among different groups such as gender, marriage, and academic grade. The concurrent validity was tested by using Pearson’s(r) correlation between the BDI-13 and other tools. The internal consistency was measured by using the Cronbach’s α coefficients. The construct validity was evaluated by using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and fit indices including chi square/df (χ2/df), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and Root Mean Square Residual (RMR)).

The accuracy of questionnaires was compared against the psychiatrist diagnosis using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC). The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, negative values, and optimal cut-off points were calculated for each screening tool.

Results

The study recruited a total of 442 students; however, 400 participants (90.49%) completed questionnaires and the SCID interview. Among participants, 206 (51.5%) were male, and 194 (48.5%) were female, and the mean age was 23.67 ± 5.37 years, with a range between 18 and 47 years. Demographic characteristics of the participants and mean differences between groups are presented in Table 1.

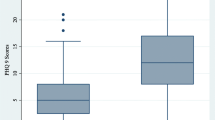

The scores of PHQ-2, WHO-5, PHQ-9, and BDI-13 in males (1.92, SD = 1.6; 9.46, SD = 6.3; 6.72, SD = 5.5; 6.92, SD = 8.5, respectively) and females (1.64, SD = 1.5; 8.85, SD = 6.5; 5.54, SD = 5.1; 4.04, SD = 5.8, respectively) were significantly different for BD_13 (P = 0.028) and PHQ-9 (P = <.001). The internal consistency of PHQ-2, WHO-5, PHQ-9, and BDI-13 was 0.73, 0.94, .88, and .94, respectively. Factor loadings were greater than the threshold value of .40. The internal consistency of each tool measured and results indicated in Table 2.

The CFA was conducted for each tool to test their construct validity. Goodness of fit indices, including normed fit index, relative fit index, incremental fit index, Tucker-Lewis index, comparative fit index, and root mean square error of approximation, were satisfactory. Table 3 shows the CFA results.

Concurrent validity of the scales was assessed by using Pearson correlation analysis. Results indicated that PHQ-2 (r = 0.53), WHO-5 (r = 0.54), and PHQ-9 (r = 0.60) total mean scores were statistically significant (P < 0.001) with BDI-13. Correlations between other tools were also statistically significant (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2, r = 0.86; PHQ-9 and WHO-5, r = 0.68; PHQ-2 and WHO-5, r = 0.66; P < 0.001).

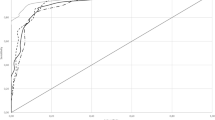

The area under the ROC curve of PHQ-9 (AUC: 0.851, 95% CI: 0.814–0.888), WHO-5 (AUC: 0.823, 95% CI: 0.782–0.863), and PHQ-2 (AUC: 0.809, 95% CI: 0.767–0.851) indicates that PHQ-9 provided significantly higher level of discrimination for mild depression (See Fig. 1).

Accuracy, including sensitivity and specificity of the different cut-off points for the PHQ-2, PHQ-9, and WHO-5, is presented in Table 4. The best cut-off point was obtained for mild depression (cut-off point: 2, sensitivity: 80.22%, specificity: 66.51%; cut-off point: 5, sensitivity: 84.62%, specificity: 70.18%; cut-off point: 9, sensitivity: 79.12%, specificity: 70.64%, respectively). The results shown in Table 4 indicate that PHQ-9 has the highest accuracy and could effectively discriminate between students with and without mild depression.

Discussion and Conclusion

We aimed to validate the WHO-5, PHQ-9, and PHQ-2 screening tools for depression among Iranian medical sciences students. Consistent with the previous studies in different populations (Arroll et al. 2010; Kroenke et al. 2001), the internal consistency of the tools was satisfactory. The concurrent validity results indicated that these tools are significantly correlated with the BDI-13, thereby confirming the results of the previous studies (Cameron et al. 2011; Dum et al. 2008). We also examined the goodness of fit for the unidimensional structure of the PHQ-9 and WHO-5 and three dimensions of the BDI-II (cognitive, somatic, and affective symptoms). In line with prior studies (Al-Turkait and Ohaeri 2010; Guðmundsdóttir et al. 2014; Keum et al. 2018), the results indicated the satisfactory goodness of fit for the tools.

Incorporating the sensitivity and specificity, the AUC calculated for each tool to estimate the probability that a tool will correctly classify students as depressed or non-depressed (Hanley and McNeil 1982). The AUC values were greater than .80 indicating that the screening tools were successful (Holmes 1998). The results indicated that the validity of the WHO-5 (.823), PHQ-9 (.851), and PHQ-2 (.809) was supported by the excellent discrimination AUC value. The cut-off point of mild depression for the PHQ-9 was recommended as five (Kroenke et al. 2001). The current study confirmed this result, and it was optimal when screening mild depression among the participants. The sensitivity and specificity values at this cut-off point were 84.62 and 70.18, respectively. These findings suggested that the PHQ-9 is a successful tool in screening depression among students. Further, the original cut-off point for mild depression in the PHQ-2 was recommended as three (Kroenke et al. 2003). However, our findings found the cut-off point as two for the optimal discrimination with the sensitivity and specificity of 80.22 and 66.51, respectively. However, the optimal cut-off point for depression screening among adolescents was recommended as nine (Allgaier et al. 2012). The present study confirmed this result, and the sensitivity and specificity values at this cut-off point were 79.12 and 70.64, respectively.

In conclusion, it is important to note that the PHQ-9, PHQ-2, and WHO-5 are brief, easy to use, valid, and reliable tools in screening depression among Iranian medical university students. The cut-off points of two, five, and nine are recommended to identify students with minor depressive disorder using the PHQ-2, PHQ-9, and WHO-5, respectively. The PHQ-9 had the highest AUC value, and therefore, it is highly recommended to apply the PHQ-9 for screening and follow-up assessment.

The participants received the SCID reference standard assessment after the screening tests. This was one of the strengths of the study. However, the study has certain limitations. First, the test-retest reliability was not performed by collecting follow-up data since face to face interactions were stopped because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, the participants were recruited by the convenient sampling method, and medical students cannot be representative of the entire student population in Iran. Therefore, further studies should be conducted with a larger sample recruited by random sampling methods.

References

Allgaier, A.-K., Pietsch, K., Frühe, B., Prast, E., Sigl-Glöckner, J., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2012). Depression in pediatric care: Is the WHO-five well-being index a valid screening instrument for children and adolescents? General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(3), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.01.007.

Al-Turkait, F. A., & Ohaeri, J. U. (2010). Dimensional and hierarchical models of depression using the Beck depression inventory-II in an Arab college student sample. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-60.

Arroll, B., Goodyear-Smith, F., Crengle, S., Gunn, J., Kerse, N., Fishman, T., Falloon, K., & Hatcher, S. (2010). Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. The Annals of Family Medicine, 8(4), 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1139.

Beard, C., Hsu, K. J., Rifkin, L. S., Busch, A. B., & Björgvinsson, T. (2016). Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.075.

Cameron, I. M., Cardy, A., Crawford, J. R., du Toit, S. W., Hay, S., Lawton, K., Mitchell, K., Sharma, S., Shivaprasad, S., & Winning, S. (2011). Measuring depression severity in general practice: Discriminatory performance of the PHQ-9, HADS-D, and BDI-II. British Journal of General Practice, 61(588), e419–e426. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X583209.

Dadfar, M., & Kalibatseva, Z. (2016). Psychometric properties of the persian version of the short beck depression inventory with Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Scientifica, 2016, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8196463.

Dadfar, M., Kalibatseva, Z., & Lester, D. (2018a). Reliability and validity of the Farsi version of the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) with Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy, 40(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0116.

Dadfar, M., Momeni Safarabad, N., Asgharnejad Farid, A. A., Nemati Shirzy, M., & Ghazie pour Abarghouie, F. (2018b). Reliability, validity, and factorial structure of the World Health Organization-5 well-being index (WHO-5) in Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy, 40(2), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0044.

Dadfar, M., Salabifard, S., Dadfar, T., Roudbari, M., & Moneni Safarabad, N. (2019). Validation of the patient health questionnaire-2 with Iranian students. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 22(10), 1048–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1699042.

Dum, M., Pickren, J., Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (2008). Comparing the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 with outpatient substance abusers. Addictive Behaviors, 33(2), 381–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.017.

Farabaugh, A., Nyer, M. B., Holt, D. J., Fisher, L. B., Cheung, J. C., Anton, J., Petrie, S. R., Pedrelli, P., Bentley, K., & Shapero, B. G. (2019). CBT delivered in a specialized depression clinic for college students with depressive symptoms. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 37(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-018-0300-z.

Ferreira, T., Sousa, M., & Salgado, J. (2019). Brief assessment of depression: Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9). The Psychologist: Practice & Research Journal, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.33525/pprj.v1i2.36.

Gilbody, S., Sheldon, T., & House, A. (2008). Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: A meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(8), 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070281.

Guðmundsdóttir, H. B., Ólason, D. Þ., Guðmundsdóttir, D. G., & Sigurðsson, J. F. (2014). A psychometric evaluation of the Icelandic version of the WHO-5. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(6), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12156.

Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1982). The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology, 143(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747.

Hill, R. M., Yaroslavsky, I., & Pettit, J. W. (2015). Enhancing depression screening to identify college students at risk for persistent depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 174, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.025.

Holmes, W. C. (1998). A short, psychiatric, case-finding measure for HIV seropositive outpatients: Performance characteristics of the 5-item mental health subscale of the SF-20 in a male, seropositive sample. Medical Care, 36(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199802000-00012.

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015.

Jafari, N., Farajzadegan, Z., Loghmani, A., Majlesi, M., & Jafari, N. (2014). Spiritual well-being and quality of life of Iranian adults with type 2 diabetes. Evidence-Based Complementary and alternative medicine, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/619028.

Kendrick, T., Dowrick, C., McBride, A., Howe, A., Clarke, P., Maisey, S., Moore, M., & Smith, P. W. (2009). Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: Analysis of medical record data. Bmj, 338, b750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b750.

Keum, B. T., Miller, M. J., & Inkelas, K. K. (2018). Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the PHQ-9 across racially diverse U.S. college students. Psychological Assessment, 30(8), 1096–1106. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000550.

Khamseh, M. E., Baradaran, H. R., Javanbakht, A., Mirghorbani, M., Yadollahi, Z., & Malek, M. (2011). Comparison of the CES-D and PHQ-9 depression scales in people with type 2 diabetes in Tehran, Iran. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-61.

Klemanski, D. H., Curtiss, J., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2017). Emotion regulation and the transdiagnostic role of repetitive negative thinking in adolescents with social anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9817-6.

Kohrt, B. A., Luitel, N. P., Acharya, P., & Jordans, M. J. (2016). Detection of depression in low resource settings: Validation of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and cultural concepts of distress in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0768-y.

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2010). The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006.

Lei, X.-Y., Xiao, L.-M., Liu, Y.-N., & Li, Y.-M. (2016). Prevalence of depression among Chinese University students: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72998-1.

Liu, S.-I., Yeh, Z.-T., Huang, H.-C., Sun, F.-J., Tjung, J.-J., Hwang, L.-C., Shih, Y.-H., & Yeh, A. W.-C. (2011). Validation of patient health questionnaire for depression screening among primary care patients in Taiwan. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(1), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.04.013.

Manea, L., Gilbody, S., & McMillan, D. (2012). Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(3), E191–E196. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110829.

Nezam, S., Golwara, A. K., Jha, P. C., Khan, S. A., Singh, S., & Tanwar, A. S. (2020). Comparison of prevalence of depression among medical, dental, and engineering students in Patna using Beck’s depression inventory II: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(6), 3005–3009. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_294_20.

Omani-Samani, R., Maroufizadeh, S., Almasi-Hashiani, A., & Amini, P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and its determinant factors among infertile patients in Iran based on the PHQ-9. Middle East Fertility Society Journal, 23(4), 460–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mefs.2018.03.002.

Paus, T., Keshavan, M., & Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 947–957. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513.

Sarokhani, D., Delpisheh, A., Veisani, Y., Sarokhani, M. T., Manesh, R. E., & Sayehmiri, K. (2013). Prevalence of depression among university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Depression research and treatment, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/373857.

Smith Fawzi, M. C., Ngakongwa, F., Liu, Y., Rutayuga, T., Siril, H., Somba, M., & Kaaya, S. F. (2019). Validating the patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening of depression in Tanzania. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 31, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2018.11.002.

Thombs, B. D., Coyne, J. C., Cuijpers, P., De Jonge, P., Gilbody, S., Ioannidis, J. P., Johnson, B. T., Patten, S. B., Turner, E. H., & Ziegelstein, R. C. (2012). Rethinking recommendations for screening for depression in primary care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(4), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.111035.

Wu, S. F. (2014). Rapid screening of psychological well-being of patients with chronic illness: Reliability and validity test on WHO-5 and PHQ-9 scales. Depression Research and Treatment, 2014, 239490–239499. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/239490.

Zuithoff, N. P., Vergouwe, Y., King, M., Nazareth, I., van Wezep, M. J., Moons, K. G., & Geerlings, M. I. (2010). The patient health questionnaire-9 for detection of major depressive disorder in primary care: Consequences of current thresholds in a crosssectional study. BMC Family Practice, 11(1), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design, implementation, analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Aims of the study had been explained to participants and informed consent was obtained from the students.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghazisaeedi, M., Mahmoodi, H., Arpaci, I. et al. Validity, Reliability, and Optimal Cut-off Scores of the WHO-5, PHQ-9, and PHQ-2 to Screen Depression Among University Students in Iran. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 1824–1833 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00483-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00483-5