Abstract

Background

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a brief tool to assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. This study aimed to validate and calibrate the PHQ-9 to determine appropriate cut-off points for different degrees of severity of depression in Argentina.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study on an intentional sample of adult ambulatory care patients with different degrees of severity of depression. All patients who completed the PHQ-9 were further interviewed by a trained clinician with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Reliability and validity tests, including receiver operating curve analysis, were performed.

Results

One hundred sixty-nine patients were recruited with a mean age of 47.4 years (SD = 14.8), of whom 102 were females (60.4%). The local PHQ-9 had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and satisfactory convergent validity with the BDI-II scale [Pearson’s correlation = 0.88 (p < 0.01)]. For the diagnosis of Major Depressive Episode (MDE) according to the MINI, a PHQ-9 ≥ 8 was the optimal cut-off point found (sensitivity 88.2%, specificity 86.6%, PPV 90.91%). The local version of PHQ-9 showed good ability to discriminate among depression severity categories according to the BDI-II scale. The best cut off points were 6–8 for mild cases, 9–14 for moderate and 15 or more for severe depressive symptoms respectively.

Conclusions

The Argentine version of the PHQ-9 questionnaire has shown acceptable validity and reliability for both screening and severity assessment of depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Major Depressive Episodes (MDE) are one of the leading causes of the global disease burden [1]. In severe cases, depression can lead to suicide, which is associated with the loss of about 850,000 lives each year [2]. Mental disorders are disabling and often co-morbid with chronic physical diseases, such as cardiovascular disease [3,4,5].

It has been estimated that about 20% of adults in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) suffer from mental health or substance use disorder each year [6]. In Latin America, depressive disorders are the leading cause of DALYs (disability-adjusted life year) among women and the fourth cause of DALYs among men [7]. Specifically, in Argentina, the age-standardized DALY rate due to depressive disorders reached 795.7 per 100.000 in 2013 [8]. A review of epidemiological studies in general population of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Puerto Rico, during the last 20 years, has shown a 12-month prevalence of major depression of 4.9% [7]. Despite its relevance to public health, depression is often unrecognized and untreated in primary care [9,10,11].

There is a variety of available instruments to assess depressive symptoms, but most of them have been developed in high-income countries and have not been cross-culturally adapted or validated for their use in LMIC [12]. The nine-item PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), extensively validated in many countries, is one of the most commonly used tools for diagnosis and severity assessment of depression [13]. However, it has not been validated for its use in Argentina.

The PHQ-9 is a short, self-administered questionnaire, widely used for screening of depression in primary care settings [14], and detection of this condition in large epidemiological studies [15,16,17,18]. Because this instrument is based on DSM- IV criteria, those scoring high are often cases with Major Depressive Episode (MDE). Further, it can also be used to assess the severity of depression by identifying from mild to severe cases. However, there is growing evidence that cut-off points for determining the degree of severity may vary depending on different contexts [19,20,21,22].

Although there is a cross-culturally adapted version of the PHQ-9 in Spanish for Argentina [23], this version has not been formally validated. Additionally, the appropriate cut-off points were not ascertained to assess the severity of symptoms. Thus, the aim of this study was to validate and calibrate the PHQ-9 to determine the appropriate cut-off points to assess different degrees of severity of depression in the adult population of Argentina.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted on adults with different degrees of severity of depression as well as individuals with no depressive symptoms. The study sample was obtained between December 2013 and March 2014. Patients were recruited from two primary care clinics and two specialty mental health outpatient facilities, both from the City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The out-patient facilities were: 1) the “Dr. Braulio A. Moyano” Hospital, which is a public neuropsychiatric hospital serving a large urban catchment area predominantly of low-income, uninsured patients; and 2) the “Foro Foundation”, a private outpatient facility treating high-income patients. The primary care clinics were: 1) The “Cooperativa de Grupo de Práctica de Medicina Familiar”, a private primary care center that treats middle-income insured patients from anywhere in Buenos Aires; and 2) the “Centro HORUS”, a private institution specialized in mental health with a multidisciplinary approach serving middle-income patients.

A purposeful quota sampling approach of persons attending these facilities was used in the study. Participants were recruited from two sources: 1) Patients referred by physicians because of the previous diagnosis of depression, and 2) patients who asked for an appointment for other health problems were approached and invited to participate. In both cases, all patients were invited to participate and asked for their signed informed consent.

Patients were recruited until the fulfillment of four quotas defined as follows: (no depression, mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of depression), according to the Beck Depression Inventory described below. A minimum of thirty patients per category was set for quota sampling.

Patients were included if they were able and willing to consent, aged 21 years or older, and were native speakers of Spanish. Exclusion criteria only applied to patients who were illiterate.

Study instruments

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

We used the existing Argentinian version of the PHQ-9 instrument, which went through a full cross-cultural adaptation process [23].

This is a nine-item self-reported scale, developed to diagnose the presence and severity of depressive symptoms in primary care and the community. It is based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for Major Depression Episode and it has the potential to be a dual-purpose instrument that can establish a tentative diagnosis of a depressive episode as well as depressive symptoms severity [24]. Each question in the scale has four response choices: “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.”

In the present study, we will validate and calibrate the PHQ-9 as a continuous measure.

The continuous measure is a summary score ranging from 0 to 27 and is calculated by adding up the responses to the nine questions, which allows assessing the presence and severity of a depressive episode [24]. The initial cut-off points proposed by the authors for the US population were as follows: ≥10 for diagnosis of MDE. Regarding severity, PHQ-9 comprises five categories, where a cut-off point of 0–4 indicates no depressive symptoms, 5–9 mild depressive symptoms, 10–14 moderate depressive symptoms, 15–19 moderately-severe depressive symptoms, and 20–27 severe depressive symptoms [25].

MINI-international neuropsychiatric interview Spanish version 5.0 (henceforth MINI): 6

The Spanish version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [26] was used as the gold standard for identifying the presence or absence of major depressive episode. The MINI interview is a validated tool used to diagnose minor and major depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), and is similar to the SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) in operation and principle [27]. This short structured diagnostic interview explores the major Axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10. Studies of validity and reliability have been conducted comparing the MINI to the SCID-P for DSM-III-R and CIDI (a structured interview developed by the World Health Organization for non-clinical interviewers for ICD-10). The results of these studies have shown that not only the MINI score has acceptably high validity and reliability, but also it can be administered in a much shorter period (18.7 ± 11.6 min, average 15 min) compared to the instruments mentioned above [28]. Direct clinical examination by a psychiatrist administering the Major Depressive Episode (MDE) and Dysthymia modules of the MINI was undertaken. The MDE module determined the standard diagnostic practice for the present study, while the Dysthymia module just helped us to capture the patients with lower levels of depressive symptomatology but who did not meet the MDE criteria.

Beck depression inventory second edition (hereafter BDI-II)

The locally validated version of the Beck Depression Inventory Second edition (BDI-II) was used as an instrument to ascertain symptom severity [29]. The BDI-II can be used as a self-reported questionnaire or administered by a physician. This questionnaire comprises 21 items, where each symptom is rated for the past two weeks, including the present-day on a four-point rating scale (0–3). The sum score ranges from 0 to 63. The following four severity levels are suggested: scores between 0 and 13 indicate minimal symptoms, from 14 to 19 mild, between 20 and 28 moderate, and from 29 to 63 severe symptoms of depression [29]. BDI-II has shown good psychometric properties across several settings [30, 31]. In our study, the BDI-II questionnaire was administered by trained clinicians.

We decided to address the inherent difficulty given by the fact that PHQ-9 defines five categories of depression while the BDI-II defines only four, because to our knowledge BDI-II was the unique instrument for depression screening validated in Argentina at the beginning of the study. So, in our study, the moderately severe and severe categories of the original PHQ-9 were expected to correspond to the severe category of BDI-II.

Data collection

The PHQ-9 was self-administered, while a trained clinician conducted a structured interview (MDE, or MDE and Dysthymia modules of MINI) and applied the BDI-II questionnaire. Only those individuals who did not meet criteria for MDE received the Dysthymia module, as we wanted to ascertain how many of those classified as ‘no depressed’ could present low levels of depressive symptomatology. To minimize a possible response bias induced by the sequence of administration of the instruments, two random sequences were used as follows: a) MINI, BDI-II and PHQ-9, and b) PHQ-9, MINI, and BDI-II. All the clinicians who conducted the interviews were blinded to the results of the PHQ-9.

Additionally, we collected information on age, gender, level of education, marital status, employment, and health coverage.

Statistical analysis

Considering expected values of sensitivity between 85 and 88%, and specificity between 92 and 95%, we calculated a minimum sample size required of 40 participants for each level of severity of depression and 30 healthy subjects with no depressive symptoms. For the sample size calculation we used the “Epidat 4.1”, free statistical software developed by Dirección Xeral de Innovación e Xestión da Saúde Pública de la Consellería de Sanidade (Xunta de Galicia) and funded by PAHO and WHO.

Criterion validity was evaluated through the comparison of the scores obtained with the PHQ-9 with the MINI interview for diagnosis, and BDI-II for the severity of depression. We calculated sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV).

To determine the most appropriate cut-off points for PHQ-9 receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were generated and Youden index was calculated using the PHQ-9 summary score, where the results for depression diagnosis and severity were obtained from MINI and BDI-II respectively. All estimates were given with 95% confidence intervals.

To determine the optimal cut-off points, the area under the curve (AUC) and the PPV and NPP were evaluated and compared to the original cut-off points suggested by the authors of the original scale [25]. The AUC for different cut-off points were compared using the non-parametric statistical method described by Hanley & McNeil [32]. Youden’s index was calculated as (sensitivity + specificity – 1) [33]. The most accurate cut-off point for diagnosis and for each category of depression severity was ascertained. The Cronbach Alpha coefficient was used for measuring reliability. All data analyses were done with STATA 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The data were analyzed with dysthymia cases included as “not depressed” and also excluding them to evaluate eventual changes in the results.

Results

A total sample of 169 subjects was recruited, 102 women (60.4%) and 67 men (39.6%). The mean age was 47.4 (SD 14.8 years). Thirty-eight percent of them were secondary school graduates, and 14.8% were unemployed. Thirty percent of participants were married or had a partner, and 77% had social or private health insurance (Table 1). The mean BDI-II score was 21 (SD = 13.4) with a median score of 20 points (IQR = 19).

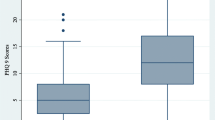

Criterion validity analysis for diagnosis of depression against MINI

We examined the performance of PHQ-9 against the diagnosis of MDE by MINI as the gold standard. According to MINI, 102 patients (60.36%) met the diagnosis of DSM-IV MDE. The mean PHQ-9 score for these patients was 14.76 (SD = 5.65), whereas the mean score for patients without diagnosis of MDE was 4.16 (SD = 4.01).

The validity of the PHQ-9 score as a continuous measure was also assessed. Table 2 depicts the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and positive and negative likelihood ratio for different thresholds for diagnosing MDE against MINI. At the cut-off score of 8 or higher, the sensitivity was 88.2%, and the specificity was 86.6% (see Table 2). In addition, at this cut-off point of 8, we obtained a Youden index of J = 0.75 and 87.6% of subjects were correctly classified. An area under the curve (AUC) of 0.87 (95% CI 0.82; 0.92) also suggests good accuracy. (See Fig. 1: ROC Curve for diagnosis of MDE according to the MINI compared with the PHQ-9).

We analyze the data with dysthymia cases included as “not depressed” first and excluding them from the analysis subsequently but the results were unaltered either way, most likely because there were only few cases (n = 16) of dysthymia.

Finally, the total score of PHQ-9 was compared with the BDI-II score. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between PHQ-9 and BDI-II was 0.88 (p < 0.01) indicating a positive and strong correlation between both instruments. (See Fig. 2: Correlation between BDI-II and PHQ-9 scores).

Criterion validity analysis for depression severity assessment against BDI-II

As recommended for the Argentinean version of the BDI-II, the following categories of severity were considered: 0–13 for minimal symptoms/no depression, 14–19 for mild symptoms, 20–28 for moderate symptoms and 29–63 for severe symptoms [28].

The performance of the PHQ-9 against the different categories of severity of depressive symptoms using BDI-II as a criterion standard can be seen in Tables 3, 4, and 5. The optimal cut-off points were 6–8 for mild, 9–14 for moderate and 15 or higher for severe depressive symptoms, respectively. These thresholds showed good sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and positive and negative likelihood ratio for each category. Sensitivity ranged between 82.4% for severe symptoms to 95.3% for moderate symptoms. Specificity varied from 80.9% (moderate) to 90.4% (mild).

High AUC estimates were also seen for all categories. AUC for mild, moderate and severe depressive symptoms was 0.91 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.96), 0.88 (95% CI 0.83 to 0.93) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.92) respectively (See Fig. 1): ROC Curve- Mild symptoms of depression with PHQ-9 compared to BDI-II; Fig. 1: ROC Curve- Moderate symptoms of depression with PHQ-9 compared to BDI-II, and Fig. 1: ROC Curve- Severe symptoms of depression with PHQ-9 compared to BDI-II).

For measuring mild symptoms of depression, a cut-off of 6 or higher showed high sensitivity (91.5%) and specificity (90.4%) and yielded a Youden index of J = 0.82 that represented 91.12% of subjects correctly classified. When comparing AUC for a cut-off point of 6 and for a cut- off point of 5 (recommended by the original authors) the difference was not statistically significant (CI overlapped). A cut-off point of 5 showed an AUC 0.85 (95% CI 0.79–0.91) whereas a cut-off point of 6 showed an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI 0.86–0.95).

Regarding moderate symptoms of depression, at the cut-off point of 9, the sensitivity was high (95.3%) but the specificity was lower but still adequate (81.0%) and the Youden index was J = 0.76. This classification yielded 88.17% of subjects correctly classified. When comparing AUC for a cut-off point of 9 and for a cut- off point of 10 (recommended by the original authors) the difference was not statistically significant (CI overlapped). A cut-off point of 9 showed an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI 0.83–0.93) whereas a cut-off point of 10 showed an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.82–0.92).

Finally, the best cut-off point to measure severe depressive symptoms was 15 or higher, with a sensitivity of 82.4% and a specificity of 89.0%. Using that cut-off point, we obtained a Youden index of J = 0.71 and the PHQ-9 questionnaire correctly classified 86.98% of the subjects. In this case, as a comparison of both ROC curves for the cut-off point of 15 and the cut- off point of 20 (the recommended by original authors) a significant difference was obtained. Cut-off point of 15 showed AUC 0.86 (95% CI 0.80–0.92) and cut-off point of 20 showed AUC 0.67 (95% CI 0.60–0.74). Optimal cut-off points for the Argentinian version of PHQ-9 are shown in Table 6.

Regarding internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total PHQ-9 scale was 0.87.

Discussion

There is a large body of evidence on PHQ-9 validation against MDE diagnosis from different countries and populations [19, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. However, there are few studies assessing calibration on severity categories [20, 21], despite a strong recommendation to explore score severity thresholds across diverse populations. [19, 22]. To our knowledge, this is the first validation and calibration study of the PHQ-9 in Argentina.

The internal consistency of PHQ-9 in this study was high and similar to the values found in other studies, which ranged from 0.67 to 0.89 [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. It has been suggested that a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 or greater should be regarded as acceptable for a self-reported instrument [51].

When the PHQ-9 was examined for detecting MDE as a continuous measure, its validity was supported by an AUC value of 0.87, which suggests a high diagnostic accuracy. The sensitivity at the cut-off value of 8 or higher was 88.2%, and the specificity was 86.6%. These values, in particular, the specificity, are higher than those reported in two meta-analyses using PHQ-9 as a continuous measure for diagnosis of major depressive episodes [52, 53]. Furthermore, according to another recent meta-analysis, the adequate cut-off points for diagnosing MDE ranged from 8 to 11 [53]. These results, together with the cut-off point of 8 or higher suggested by another study [20] are also consistent with our results. A cut-off point of 8 showed an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.82–0.93) whereas a cut-off point of 10 showed an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI 0.80–0.90). However, as expected, the sensitivity obtained with a lower threshold was higher, which becomes relevant since this instrument is intended to be used in primary care settings and population-based research.

For the present study, the MDE module of the MINI (time frame of two weeks) determined the standard diagnostic practice. While the use of Dysthymia module of the MINI (time frame of two years) just helped us to capture the patients with lower levels of depressive symptomatology but who do not reach MDE criteria. As we explained before, only those individuals who did not meet criteria for MDE received the Dysthymia module. We found that including or excluding these patients did not alter the results at all, something that was expected as there were few cases of dysthymia.

Of note, the PHQ-9 score was highly correlated with the BDI-II score. This correlation was even higher than that reported by Kneipp et al. (Pearson Correlation Coefficient = 0.80) when comparing the same instruments in low-income female populations [44]. Our results indicate a positive, strong association between both instruments, which further support the validity of the PHQ-9 measurements in this population.

Regarding the comparison of categories of severity and despite the inherent difficulty given by the fact that PHQ-9 defines five categories of depression while the BDI-II defines only four, the optimal cut-off points for the Argentine version of PHQ-9 generated the same four categories, as found in other studies (see Table 6) [11, 12]. These categories are also defined according to the DSM-IV. The thresholds for all four categories, 6–8 for mild, 9–14 for moderate and 15 or higher for severe depressive symptoms respectively showed good sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and positive and negative likelihood ratio. Of note, in the Argentinean version, the moderately severe and severe categories of PHQ-9 correspond to or could be included in the severe category of BDI-II. Since, the therapeutic approach for both, moderate-severe or severe patients, it is similar; although this misalignment of the scale categories is not ideal, it doesn’t have a relevant impact for screening or therapeutic approach purposes.

This validation study of the PHQ-9 for the Argentinean population has several strengths. First, it was rigorously designed to have an adequate representation of all the stages of severity of depression, including patients with non-depressive symptoms, which is key to ensure not only its validity for diagnosis of depression but also its calibration for different categories of severity; Secondly, we chose a criterion tool that is shorter than other diagnostic tools available in Argentina for identifying depressive cases [25], something that is important in primary care. Thirdly, the PHQ-9 is useful to assess not only the presence of clinical depression but also its degree of severity. Specifically, for severity measures, this Argentine version provides locally adjusted thresholds and follows recommendations to adapt the instrument to the context and setting where the tool is aimed to be implemented [19, 22]. Finally, its use is increasingly being valued in epidemiological research because it is brief and can be scored in a very simple way, providing a continuous measure that is easier to interpret in large epidemiological studies [15,16,17,18].

Our study presents some limitations. First, since this study has focused mainly on the city dwellers of Buenos Aires and its surroundings, its extrapolation to rural settings should be taken with caution. Yet, its usability seems to be enhanced by the fact that 90% of the Argentine population lives in urban areas. Second, the sample composition is heterogeneous with patients coming from primary and secondary care settings as well as private and state sectors. Nonetheless, this might allow us to extrapolate findings to other clinical populations. Third, we administered the instruments in a different order to avoid eventually bias, but we have not done additional analyses to ascertain if this had an impact on results. Fourth, since the PHQ-9 defines five categories of depression while the BDI-II defines only four, the optimal cut-off points for the Argentine version of PHQ-9 generated the same four categories. However, it may not have a relevant impact on screening or intervention purposes because it doesn’t condition the therapeutic approach.

Conclusions

The Argentine version of the PHQ-9 questionnaire has shown acceptable validity and reliability for both screenings of Major Depressive Episodes and severity assessment of depressive symptoms. A definite diagnosis would ideally be attained; however, with a complementary psychiatric interview; a tool that is not always available in primary care settings. Therefore, this validated and calibrated tool could improve and facilitate the detection, classification and monitoring of depressive disorders in Argentina, particularly in the primary care setting, where depression still goes unnoticed and therefore undertreated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory- II

- CIDI:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- DSM-III-R:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third-Research Edition

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- ICD-10:

-

International classification of diseases. Tenth edition

- MDD:

-

Major Depressive Disorder

- MDE:

-

Major Depressive Episode

- MINI:

-

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- NPV:

-

Negative Predictive Value

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire- 9

- PPV:

-

Positive Predictive Value

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operational Curve

- SCID:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

References

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–57.

Marcus M, Taghi M, Van Ommeren M, Chisholm D, Saxena S. In: Abuse WDMHS, editor. Depression: a global public health concern in. Mental Health, Disorders Management: World Health Organization; 2012.

Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1365–72.

Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, Califf RM, Krishnan RR, O'Connor CM. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154(1):102–8.

Gerontoukou EI, Michaelidoy S, Rekleiti M, Saridi M, Souliotis K. Investigation of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic diseases. Health Psychol Res. 2015;3(2):2123.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(21):2581–90.

Kohn R, Levav I, de Almeida JM, Vicente B, Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Saxena S, Saraceno B. Mental disorders in Latin America and the Caribbean: a public health priority. Revista panamericana de salud publica = Pan American journal of public health. 2005;18(4–5):229–40.

Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Abbasoglu Ozgoren A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abraham JP, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–91.

Patel V, Araya R, Bolton P. Treating depression in the developing world. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2004;9(5):539–41.

Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bromet EJ, Burger H, Demyttenaere K, de Girolamo G, et al. Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2008;192(5):368–75.

Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Tat Chiu W, G DEG, Fayyad J, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's world mental health survey initiative. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 2007;6(3):177–85.

McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaire. In. New York: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS; 2006.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59.

Kung S, Alarcon RD, Williams MD, Poppe KA, Jo Moore M, Frye MA. Comparing the Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II) and patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression measures in an integrated mood disorders practice. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(3):341–3.

Michal M, Wiltink J, Lackner K, Wild PS, Zwiener I, Blettner M, Munzel T, Schulz A, Kirschner Y, Beutel ME. Association of hypertension with depression in the community: results from the Gutenberg health study. J Hypertens. 2013;31(5):893–9.

van Dooren FE, Denollet J, Verhey FR, Stehouwer CD, Sep SJ, Henry RM, Kremers SP, Dagnelie PC, Schaper NC, van der Kallen CJ, et al. Psychological and personality factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus, presenting the rationale and exploratory results from the Maastricht study, a population-based cohort study. BMC psychiatry. 2016;16(1):17.

Elperin DT, Pelter MA, Deamer RL, Burchette RJ. A large cohort study evaluating risk factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16(2):149–54.

Tracy M, Morgenstern H, Zivin K, Aiello AE, Galea S. Traumatic event exposure and depression severity over time: results from a prospective cohort study in an urban area. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(11):1769–82.

Kiely KM, Butterworth P. Validation of four measures of mental health against depression and generalized anxiety in a community based sample. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):291–8.

Haddad M, Walters P, Phillips R, Tsakok J, Williams P, Mann A, Tylee A. Detecting depression in patients with coronary heart disease: a diagnostic evaluation of the PHQ-9 and HADS-D in primary care, findings from the UPBEAT-UK study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78493.

Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Friedman M, Boerescu DA, Attiullah N, Toba C. Speaking a more consistent language when discussing severe depression: a calibration study of 3 self-report measures of depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(2):141–6.

Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, Howe A, Clarke P, Maisey S, Moore M, Smith PW. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ. 2009;338:b750.

Bonicatto SG, P; Tutor, C; Lucero, S; Güenaga, F; Torino, D.: Screening of mental disorders in primary care: linguistic adaptation procedure of a diagnostic instrument. In., vol. 45(3): Acta psiquiátr. psicol. Am. Lat; 1999: 223–234.

Kroenke K, Spitzer R. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–15.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Ferrando L, Bobes J, Gibert J. In: Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, editors. M.I.N.I: Mini international neuropsychiatric interview version en español 5.0.0. Copyright 1992–2004. Spain: University of South Florida, Tampa. Instituto IAP – Madrid – Spain; 2000.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995.

Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Bonora L, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan M, et al. Reliability and validity of the MINI international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): according to the SCID-P. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–41.

Brenlla M, Rodríguez C: Adaptación argentina del Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI-II). BDI-II Inventario de Depresión de Beck Segunda Edición Manual Buenos Aires: Paidós[Links] 2006.

Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck depression inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001;20(2):112–9.

Grothe KB, Dutton GR, Jones GN, Bodenlos J, Ancona M, Brantley PJ. Validation of the Beck depression inventory-II in a low-income African American sample of medical outpatients. Psychol Assess. 2005;17(1):110–4.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148(3):839–43.

Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–5.

Huang CQ, Dong BR, Lu ZC, Yue JR, Liu QX. Chronic diseases and risk for depression in old age: a meta-analysis of published literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(2):131–41.

Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8:46.

Liu SI, Yeh ZT, Huang HC, Sun FJ, Tjung JJ, Hwang LC, Shih YH, Yeh AW. Validation of patient health questionnaire for depression screening among primary care patients in Taiwan. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):96–101.

Chen S, Fang Y, Chiu H, Fan H, Jin T, Conwell Y. Validation of the nine-item patient health questionnaire to screen for major depression in a Chinese primary care population. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(2):61–8.

Baader MT, Molina FJL, Venezian BS, Rojas CC, Farías SR, Fierro-Freixenet C, Backenstrass M, Mundt C. Validación y utilidad de la encuesta PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) en el diagnóstico de depresión en pacientes usuarios de atención primaria en Chile. Revista chilena de neuro-psiquiatría. 2012;50:10–22.

Chagas MH, Tumas V, Rodrigues GR, Machado-de-Sousa JP, Filho AS, Hallak JE, Crippa JA. Validation and internal consistency of patient health Questionnaire-9 for major depression in Parkinson's disease. Age Ageing. 2013;42(5):645–9.

Patten SB, Burton JM, Fiest KM, Wiebe S, Bulloch AG, Koch M, Dobson KS, Metz LM, Maxwell CJ, Jette N. Validity of four screening scales for major depression in MS. Mult Scler. 2015.

Munoz-Navarro R, Cano-Vindel A, Medrano LA, Schmitz F, Ruiz-Rodriguez P, Abellan-Maeso C, et al. Utility of the PHQ-9 to identify major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care centres. BMC psychiatry. 2017;17(1):291.

Milette K, Hudson M, Baron M, Thombs BD. Comparison of the PHQ-9 and CES-D depression scales in systemic sclerosis: internal consistency reliability, convergent validity and clinical correlates. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(4):789–96.

Rogers WH, Adler DA, Bungay KM, Wilson IB. Depression screening instruments made good severity measures in a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(4):370–7.

Kneipp SM, Kairalla JA, Stacciarini JM, Pereira D, Miller MD. Comparison of depressive symptom severity scores in low-income women. Nurs Res. 2010;59(6):380–8.

Diez-Quevedo C, Rangil T, Sanchez-Planell L, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of the patient health questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):679–86.

Dum M, Pickren J, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Comparing the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 with outpatient substance abusers. Addict Behav. 2008;33(2):381–7.

Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. J Affect Disord. 2006;96(1–2):89–93.

Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the patient health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):547–52.

Hepner KA, Hunter SB, Edelen MO, Zhou AJ, Watkins K. A comparison of two depressive symptomatology measures in residential substance abuse treatment clients. J Subst Abus Treat. 2009;37(3):318–25.

Lai BP, Tang AK, Lee DT, Yip AS, Chung TK. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese men: a comparison of three instruments. Psychiatry Res. 2010;180(2–3):80–5.

Streiner DL, Cairney J. What's under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(2):121–8.

Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1596–602.

Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):E191–6.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy administrative staff for their support. We would also like to thank Fernando Rubinstein and Natalie Soto for their suggestions during the design and analysis stages.

Funding

This project has been funded with Federal funds from the United States National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under a seed grant for young trainees. The funding source played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MU, FD, AR, RA and VI designed the study and drafted the manuscript. GS, FC, GH, GT and FD conducted psychiatric interviews. MU coordinated the ethical approval process. MU, AR and VI developed all statistical analysis. MU led the study and together with AR obtained funding for it. All authors interpreted results and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the IRBs of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (ref: Protocol 2121/20130829) and Braulio A. Moyano Neuropsychiatric Hospital (ref: Protocol 004/2013), both of them located in Buenos Aires - Argentina. All participants signed a written informed consent and were informed that if a depressive episode was detected during the evaluation, they would be referred to their primary care physician or mental health clinician.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Urtasun, M., Daray, F.M., Teti, G.L. et al. Validation and calibration of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in Argentina. BMC Psychiatry 19, 291 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2262-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2262-9