Abstract

Bringing a greater number of students into science is one of, if not the most fundamental goals of science education for all, especially for heretofore-neglected groups of society such as women and Aboriginal students. Providing students with opportunities to experience how science really is enacted—i.e., authentic science—has been advocated as an important means to allow students to know and learn about science. The purpose of this paper is to problematize how “authentic” science experiences may mediate students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices. Based on a larger ethnographic study, we present the case of an Aboriginal student who engaged in a scientific internship program. We draw on cultural–historical activity theory to understand the intersection between science as practice and the mundane practices in which students participate as part of their daily lives. Following Brad, we articulate our understanding of the ways in which he hybridized the various mundane and scientific practices that intersected in and through his participation and by which he realized his cultural identity as an Aboriginal. Mediated by this hybridization, we observe changes in his orientation towards science and his career choices. We use this case study to revisit methodological implications for understanding the role of “authentic science experiences” in science education.

Samenvatting

Eén van de meest fundamentele doelen van algemeen toegankelijk natuurwetenschappelijk onderwijs is om meer leerlingen met natuurwetenschappen in aanraking te laten komen. Dit geldt in het bijzonder voor groepen die nu ondervertegenwoordigd zijn in de natuurwetenschappen, zoals vrouwen en inheemse volkeren. Een manier om studenten werkelijk in aanraking te laten komen met natuurwetenschappen, is authentiek natuurwetenschappelijk onderwijs. Er is echter nog weinig bekend over de rol die authentieke natuurwetenschappelijke ervaringen spelen in de oriëntatie van leerlingen op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières. In deze studie problematiseren we daarom de manier waarop authentieke natuurwetenschappelijke ervaringen kunnen interfereren met de oriëntatie van leerlingen op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières. In het artikel rapporteren we over een gevalsstudie over Brad, een leerling die behoort tot de Coast Salish, een inheems volk dat de kustgebieden en eilanden bevolkt in het gebied dat zich grofweg bevindt tussen de steden Seattle (Washington, VS), Victoria en Vancouver (Britisch Columbia, Canada). Brad loopt een stage waarin hij kennis maakt met twee praktijken waarin natuurwetenschappen een evidente rol spelen, namelijk een natuurbeschermingsorganisatie en een drinkwaterlaboratorium. Uitgaande van de handelingstheorie, waarin de eenheid van analyse bestaat uit praktijken, analyseren we de wisselwerking tussen de natuurwetenschappelijke en dagelijkse praktijken waaraan Brad deelneemt gedurende zijn stageprogramma. Voorts kijken we naar de manier waarop deze wisselwerking interfereert met de oriëntatie van Brad op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières. Gedurende de stage ervaart Brad dat natuurwetenschappelijke methoden en kennis een beperkte rol spelen in de beslissingen van de natuurbeschermingsorganisatie die van belang zijn voor zijn gemeenschap. Dit staat in contrast met zijn inheemse kennis van de natuur die Brad toepast in het project en daardoor leert herwaarderen. Als gevolg hiervan wordt de oriëntatie van Brad op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières kritischer; hij ambieert bijvoorbeeld geen carrière als een wetenschapper in een drinkwaterlaboratorium. Ook wordt zijn oriëntatie op natuurwetenschappen genuanceerder en geprononceerder. Hij leert bijvoorbeeld hoe zowel natuurwetenschappelijke als inheemse kennis van de natuur een rol kunnen spelen in beslissingen die van belang zijn voor zijn gemeenschap en dat het daarom van belang is om de “taal” van de natuurwetenschappen te kunnen spreken. Uiteindelijk kiest hij voor een opleiding aan een universiteit waarin natuurwetenschappen een rol spelen, maar waarin hij ook zijn inheemse kennis van de natuur kan ontwikkelen (ethnobotanie). We concluderen dat authentieke wetenschappelijke ervaringen er niet zonder meer toe hoeven te leiden dat leerlingen positieve keuzes maken voor natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières. Uitgaande van de vele verschillen tussen leerlingen en de vele verschillende handelingspraktijken waaraan zij deelnemen, veronderstellen we dat de uitkomsten van authentieke natuurwetenschappelijke ervaringen wat dat betreft heterogeen en moeilijk te voorspellen zijn. Uitkomsten van authentieke natuurwetenschappelijke ervaringen die leiden tot minder positieve oriëntatie op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières zijn bovendien ook zinvol. De meer kritische oriëntatie op natuurwetenschappen en natuurwetenschappelijke carrières van Brad ging bijvoorbeeld gepaard met een herwaardering van inheemse kennissystemen over de natuur. En dat soort uitkomsten zijn in dit geval van belang voor algemeen toegankelijk natuurwetenschappelijk onderwijs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The path followed by Brad

-

Brad (pseudonym) is a 26-year old Aboriginal male. He is a member of a First Nation that culturally is a subgroup of the Coast Salish peoples who inhabit the coastal areas and islands in the area that roughly stretches between the cities Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia. During our study, we met Brad for the first time at the community’s tribal school, when we were introduced to a number of First Nations students who had enrolled in an adult education program to prepare for future careers.

-

Brad had a relaxed, polite, thoughtful and somewhat aloof way of going, reinforced by a rather soft and slow voice. During our first meetings, this way of going reinforced in some way the distance that occurred naturally between us as strangers still unknown to each other. Later, we experienced him as gentle, willing to learn, open-minded, and gifted with wisdom of life, a good sense of humor and sharp observation skills. His way of dressing was not uncommon for people from his age group; he often wore casual sporting clothes and sunglasses. But his light clothing for the relatively cold time of the year revealed that he could often be found in the outdoors.

-

Brad was considering several future careers at the time when we met him, such as a greenery worker or as a nature conservator. Because of these interests and because he liked the outdoors, he stepped forward in response to our invitation to engage in an internship program focused on nature conservation and environmental science. At the start of the program, Brad’s orientation to science was generally positive and he considered being a scientist to be a good career. He considered nature conservation to be a typical scientific domain and could, as such, think of himself as becoming a scientist.

-

The nature conservation internships were hosted by the OceanHealth Marine Conservation Society (pseudonym), a non-profit society that is working through education and advocacy together with local communities towards the conservation and restoration of marine ecosystems in British Columbia. Brad engaged in conservation and restoration activities that involved direct action on local ecosystems, education of school children, and outreach to the wider public. One of these marine ecosystems was TÉTCEN (Tye Inlet) (pseudonym), which used to be a harvesting ground where Brad’s people had collected marine animals (clams, oysters, mussels) for centuries and hence considered sacred.

-

A substantial part of the internship consisted of science activities. Part of this consisted of the activities OceanHealth conducted as part of its daily business and in which Brad engaged, such as water quality monitoring and the mapping of eelgrass (Zostera marina) populations. During such activities, Brad learned to use scientific tools for monitoring water quality (e.g., colorimeter, dissolved oxygen meter).

-

In addition to using scientific tools in daily activities of nature conservation, the internships consisted of the engagement in purportedly authentic science activities. We took the opportunity provided by a drinking water research laboratory at our university, the chief scientist of which had opened the lab to offer authentic science experiences to students. We framed this presence in the laboratory in a meaningful context and departed from the needs of OceanHealth. Collectively, Brad and the other people working at OceanHealth decided to let the water laboratory monitor the level of pollutants (heavy metals, pesticides, volatiles) in samples of sediments and sea animals from TÉTCEN. In the process, Brad followed the trajectory of the samples through the laboratory until, in a final step, the processes yielded the data; he thereby came to observe the scientific production of the data from the beginning to the end. From the data it was concluded that TÉTCEN had been under attack of pollution for years. Still, the place was in reasonable condition and it made sense to pursue restoration and conservation. As such, the data provided evidence that could support OceanHealth to secure support for TÉTCEN from the local government. However, this turned out to be disappointing, because the government was not convinced of the need to restore the area.

-

During the internships, we paid explicit attention to future career choices and education. For instance, we setup a meeting with an Aboriginal environmental scientist who had just finished her schooling. Brad also visited a meeting of botanists at the university. This particular path through the internship program had consequences for both Brad’s orientation to science and his career choices. He recognized that the science experiences empowered him in speaking the scientific language, which he considered important for his future career. He also decided to enroll in an academic program to develop botanical expertise and acquire the required credentials for his future career. However, he was very explicit about no longer wanting to pursue the career of a scientist generally and he did not consider becoming a nature conservator more specifically.

We present this vignette because it highlights how authentic science experiences may mediate the career choices of young individuals. Here, the adjective “authentic” is taken as denoting experiences that have some family resemblance with what scientists do. “Authentic” applies to Brad because he had the opportunity to participate in science as it is conducted in scientific laboratories all the while pursuing something of his interest (gathering data about his native TÉTCEN). This is relevant in the context of decreasing numbers of students opting for scientific careers in many developed countries. To counter this situation, it is often proposed to engage students in “authentic” science, that is, forms of engagement with nature and data collection instruments that bear family resemblance with those forms of engagement scientists normally exhibit (e.g., Woolnough 2000). Such proposals draw on the premise that authentic science experiences contribute to changes in the orientation of students towards science and technology which in turn are expected to lead to an increased likelihood that they will enter careers in these areas.

The path followed by Brad, then, is interesting because, through authentic science experiences, it is in touch with the path desired by those policy makers who want the school system to produce more students opting for scientific careers. But ultimately, as we show here, his path deviates from the desired trajectories into science (among university scientists, these trajectories frequently are referred to as “pipelines”). As well, despite the fact that Brad explicitly did not choose a scientific career in the end, his path is by no means a missed opportunity or that of a dropout. On the contrary, the path followed by Brad is one of acquiring a better understanding of science and hence clearer career aims, leading to concrete choices for a future career. In this way, Brad’s trajectory is not unlike that of many of our White female high school students after they returned from their experiences of participating in doing experiments in real science laboratories.

The ultimate purpose of this paper is to problematize how authentic science experiences may mediate students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices generally and students from different cultures particularly. We briefly review the literature on this topic and point out why, to make sense of this problem, we find it opportune to adopt a cultural–historical activity theoretical framework. This framework helps us to understand the continuously mixing of cultural practices, the mêlée (Nancy 2000), occurring in the globalizing world of today in and through the participation of individuals from various origins (ethnic, geographic, professional) in those practices. We use this framework to make sense of the various mundane and scientific practices that intersected and hybridized in and through Brad’s participation. We then illustrate how our case study reveals changes in Brad’s orientation towards science and his career choices as a result of this hybridization of practices. We finally use this case study to revisit the understanding and role of “authentic science experiences” in science education.

We employ the genre of case study as a form of representing what we have learned from our research. For the case study presented in this paper, data collection included observation, taking field notes, and videotaping of Brad along with other participants in the practices in which he engaged (marine conservation and drinking water laboratory) and interviews with Brad and the other participants over the course of 10 months. In order to focus on science-related and other career aspirations of Brad, we used the Possible Selves mapping activity (Shepard and Marshall 1999) as part of the interviews. All data from the videotape and interviews were transcribed. The data were first coded with the aim to distinguish the moments of activity of the practices in which Brad engaged, such as objects, tools, and communities. A second coding of the data focused on changes in the moments of activity and the hybridization of practices through such changes. Finally, the diachronic nature of subsequent changes was reconstructed by compiling short narratives from the coded data.

As other investigators in the area of multicultural issues in science education have indicated earlier (e.g., Calabrese Barton and Yang 2000), the unique feature of case studies is their possibility to take the reader to unique places that we do not normally visit. This allows one to look at the world through the researchers’ eyes and to observe details that one might otherwise not have seen. Such details can function as logical distinctions required for reframing the hitherto familiar world around us, which is a form of generalization. Through this process, which is known in the methodology of case study as naturalistic generalization, case studies overcome the issue of sufficient generalizability. As such, based on the coded data, we narratively (re)constructed the path followed by Brad as presented in this paper.

Authentic science experiences and career choices

Our research program as part of which Brad and other students came to do their internships is concerned with scientific literacy, which is a major aim of current science education (Hurd 1998). This aim not only involves knowledge of key concepts in the natural sciences but also understanding of scientific inquiry as a human enterprise. In this context, we are interested in authentic science experiences as a vehicle to improve scientific literacy and the science career choices students make. In this section, we briefly review the literature on these two topics and provide some ethnographic background to our case study.

Authentic science experiences

The notion of authentic experiences in school emerged from scholarly pursuits in education after research had shown—mostly with respect to mathematics—that much of what people do in their everyday lives is unaffected by their school experiences (Lave 1988). The fundamental idea at the time was that literacy (knowledge) has to be understood in terms of practices—the patterned actions people deploy in their private and working lives—rather than as procedural and declarative information stored in their heads that they bring to bear on problematic situations. Thus, it was proposed that students of mathematics, science, or history engage in activities that bear considerable family resemblance with the activities in which scientists, mathematicians, or historians normally are engaged in (Brown et al. 1989). Here, knowledge is equivalent to competent participation in these activities, and learning is recognizable as changing (increasing) competence. One of the very first studies of authentic science in middle and high schools showed that there was tremendous potential in having students learn science by designing and conducting their own research programs (Roth 1995). Despite the success of this and similar studies, there emerged doubts in the science education community whether the things scientists do in their labs provide the appropriate image for the education of all students (Sherman 2004). In particular, the discourse and competition within the sciences is said to reproduce unequal levels of access for women, the poor, and those of culturally different origins (African American, First Nations) and therefore with different epistemological commitments.

For instance, during our study, we learned that the epistemological commitments common in Brad’s First Nation came close to the heshook-ish tsawalk (everything is one) worldview of the Nuu-chah-nulth, a First Nation inhabiting the Northern Pacific Coast of Vancouver Island. Epistemologically, this worldview is explained by a Nuu-chah-nulth chief as follows:

My theory appears to be similar, even identical, to some contemporary theoretical ideas that employ the concept of context in social science and environmental discourses. However, important assumptive aspects of my theory differ sharply from any Western theory. In my earlier research into student outcomes in a variety of contexts over time, I originally conceived Tsawalk as a theory of context. In one respect, context defines recognizable units of existence, such as age group, gender, home, school, geographical region, society, and heritage, but Tsawalk, by comparison, also refers to the nonphysical and to unseen powers. Consequently, because the theory does not exclude any aspect of reality in its declaration of unity and, most important, because the concept of heshook-ish tsawalk demands the assumption that all variables must be related, associated, or correlated, I now call this view of reality the theory of Tsawalk. (Atleo 2004, p. 117)

As explicated here, this epistemological commitment is radically different from the natural sciences as they are usually practiced in laboratories in the Western world. Logically, many First Nations students have difficulty with the scientific discourses in these natural sciences in which epistemological commitments common among their people, such as Tsawalk, are not acknowledged. As a result of such existential difficulties, they often opt out.

In this vein, authentic science experiences, to be effective, should aim to contribute to overcoming (rather than deepen) a dilemma articulated by Indigenous scholars dealing with the ineffectiveness of conventional science curricula. As with many students with a European background, Aboriginal students are alienated from science, but their epistemological commitments, mother tongues, identities, and worldviews create an even wider cultural gap between themselves and school science (McKinley et al. 1992). As a result, they constitute population sections least represented in science and technology careers. The dilemma follows from the question of how to solve this problem. On the one hand, such curricula should nurture students’ achievement toward formal educational credentials and economic and political independence. This includes students’ development of scientific literacy and the participation of students in pursuing scientific and engineering careers, for example by means of authentic experiences in science laboratories. On the other hand, Aboriginal scholars maintain that particularly Aboriginals from younger generations consider it important to pursue forms of Native activism (e.g., Point 1991). Native activism is rather known from forms of activity in which Aboriginals publicly pursue their political goals, such as protest meetings and awareness campaigns. In a wider meaning, Native activism concerns the many ways in which Aboriginals people expand their action possibilities while maintaining their political and epistemological commitments and hence developing their cultural identity as Aboriginals in a way they feel comfortable with. The question is thus how authentic science curricula can contribute to such aspirations. At a minimal level, then, such curricula should not indoctrinate students while engaging in scientific practices. For instance, adopting a scientific discourse as the only means of talking about the natural world around us entails the exclusion of indigenous forms of narratives about nature and therewith their systems of knowledge. This exclusion constitutes a form of symbolic violence and colonization often found as a source of indoctrination in science education (Battiste 2002).

In recent years, the notion of authentic with respect to science literacy has therefore been rethought (Roth and Barton 2004). Participation in any form of activity where science is also brought to bear on decision-making, as long as this activity is the real thing rather than a mock-up, appears to be a better image for providing meaningful science experiences to the student population at large. Thus, some of the suggested activities include participation in environmentalism, ethnobotany, and active citizenry in community-relevant affairs.

Orientation toward science and career choices

The research literature falls short when it comes to the question of how authentic science experiences may mediate students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices. There is a large body of literature that deals with students’ orientations to science in relation to science education (for a review see Osborne 2003). This literature generally points to factors that influence this orientation, such as such as gender, teachers, curricula, and culture. Multicultural studies, for instance, point to the inherent culturally biased nature of science education a reason for many ethnic minorities to opt out of science education and hence scientific careers (Hodson 1993). However, such studies do not clarify the proposed role of authentic science as a mediator of students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices. On the other hand, there is a vast body of literature dealing with authentic science experiences (e.g., Rennie et al. 2003). Unfortunately, these studies provide little detail of the relation between such forms of engagement and students’ orientations to science and inherent career choices.

In the context of this blind spot in the research literature, some studies indirectly point to evidence that authentic science experiences may serve as a means to overcome gender or cultural issues in students’ orientations to science and career choices. For instance, one study provides evidence based on suggestions of female participants indicating that career-related internships were contexts in which they considered science careers (Packard and Nguyen 2003). However, such studies do not provide direct evidence of how authentic science experiences may mediate students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices.

Despite a lack of understanding and evidence, the rhetoric frequently proposes authentic science experiences as a means to counter the decreasing numbers of students opting for scientific careers (e.g., Braund and Reiss 2006). However, little research has been carried out that warrants this premise. Moreover, outcomes of studies in the public understanding of science point to a less straightforward picture. Since the 1980s, research in this area has criticized the so-called “deficit model.” This model comes with the idea that public resistance towards science and technology is caused primarily by a lack of familiarity with science. Hence the model suggests that an individual’s orientation to science will be more positive once s/he becomes more familiar with science (e.g., Wynne 1991). Detailed studies focusing on the relation between individuals’ familiarity with and orientations to science show that this model is in fact too simplistic. Individuals’ orientations to science is highly heterogeneous and depends on, for instance, an individual’s worldview, the wider context and scientific discipline of the case under scrutiny, and the modes of surveying their orientations to science. Both the multifaceted nature of science as a human practice and the professional and mundane practices in which individuals engage can be considered determinants of this heterogeneity. Hence, to arrive at a better understanding of how authentic science experiences may mediate students’ orientations towards science and scientific career choices we need to take into account the multifaceted nature of the practices in which humans participate in and through their mundane lives.

Environmentalism and scientific research as human practices

This particular case study involving Brad was part of a larger research project in which researchers from both education and science (e.g., drinking water research lab) departments, local NGOs (e.g., OceanHealth), and schools collaborated to document the development of scientific literacy, orientation to science, and career aspirations developed by students and teachers alike through long-term ethnographic studies in authentic settings in which science is prevalent. As part of the larger study, we set up internship programs for students in collaboration with our project partners (OceanHealth, drinking water research lab), and teachers and schools. The setup of the internships was tailor-made; we departed from the situation at hand and seized the opportunities that emerged out of the participation of the people and organizations with which we collaborated. In an earlier study, we arranged an internship in collaboration with the biology teacher for a group of 23 biology honors students in an urban secondary school. In this case, the internship program was designed for a large group of students in the drinking water laboratory who were supervised by technicians in the course of a 3-week research project the students conducted.

As part of our larger project, we also wanted to get students and schools from local First Nations communities involved. OceanHealth also collaborated in this project and provided the opportunity to get in touch with First Nations communities. Particularly, we intensively collaborated with the leader of this organization who, as a general vision on environmentalism, aims to build relationships among community groups, government organizations, schools, and First Nations communities to deliver critically important programs to monitor, restore, manage, educate and raise awareness about our marine environment. Therefore, the organization works mainly locally in order to learn about the importance of a place like TÉTCEN (Tye Inlet) for communities around that particular place, including First Nations, and to build relationships. As a result, OceanHealth had already close ties with First Nations communities. For instance, they collaborated intensively with the local tribal school and the leader was deeply inspired by one of the most respected elders of a local First Nations community. Because of these well-established ties between OceanHealth and the First Nations communities, we could jump in and build upon existing relationships of mutual trust and respect. In close collaboration with OceanHealth, we setup internships with the aim to bring students from First Nations communities in touch with nature conservation and environmental science.

The internships were framed as an extension of a program offered by the local First Nations adult education centre for First Nations men and women who considered career change, returning to school, or re-entering the workplace. Among other things, the course focused on career and personal development, education and training opportunities, individual career guidance, and demystifying the college process. OceanHealth cooperated with the adult education center because the aim of our internship fitted well with the aims of the program of the First Nations adult education center. During a session of this program, we invited students to enter our internship program. Brad was one of the two Aboriginal students who responded to our offer and enrolled in the internships. The drinking water laboratory also has had fruitful collaborations with other First Nations communities in marine habitat research projects. In close collaboration with both OceanHealth and the participating students, we decided to extend the OceanHealth internships with a short, 3-day internship in the drinking water research laboratory. During this internship, Brad and the other student would visit the drinking water research laboratory with the aim to engage in the analysis of samples from local marine habitats.

Marine conservation as cultural–historical activity at the nexus with other activities

To better understand Brad’s path through several different practices we use cultural–historical activity theory (CHAT) as an analytic lens. Cultural–historical activity theory, which is rooted in the work of Soviet psychologists who maintained that human action cannot be understood outside actual praxis, has become an important tool for theorizing and understanding complex systems of societally organized activities (Roth and Lee 2007). Here, all forms of human praxis are conceived in terms of object-oriented and artifact-mediated activity. Cultural–historical activity theory is concerned with understanding real, concrete activity in the very settings where it occurs, based on the grounds individual and collective human agents have for doing what they do. Activity theory aspires to understand and explain each form of action in its concrete material detail (artifacts, objects), whatever the situation, without losing the connection to the organization of society into systems of activity. The unit of activity is dialectical in the sense that, however, we partition it, each part can be understood only in its relation to all other parts; and each part makes sense only in its relation to the whole, that is, the organization of society. Thus, this theory allows us to analyze in more detail but holistically the practices outlined in the preceding story and to analyze how human action is intelligible in such practices.

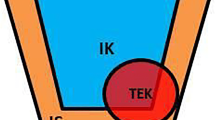

To analyze a concrete activity such as marine conservation, researchers begin by articulating the activity and then ask what its constituent structures might be. Here, the originators of the theory do not use activity to denote what (science) educators commonly understand—e.g., doing a science laboratory task—but in fact refer to a societal form of providing for the survival of all. Thus, farming, producing tools, doing scientific research, or reproducing cultural knowledge (i.e., schooling) are typical activities. The most fundamental partition in constituent structures that can be made is that between the acting subject and the object of his/her actions. For example, in this study, we analyzed Brad’s participation in the marine conservation organization OceanHealth. To understand the concrete activity of nature conservation we can ask “Who is doing the work?,” “What are they working on?,” and “What is the result?” The answer to the first question gives us the subject, individual or group (staff, interns such as Brad, and volunteers); the answer to the second question gives us the object, the raw materials involved in marine conservation, in this case, including its animals and plants. The answer to the third question gives us the outcomes of the activity, such as changes in the behavior of the surrounding human population and recreants, changes in policy of the regional government, influx of money for follow-up activities, and, ultimately desired changes in TÉTCEN. To understand marine conservation, subject and object cannot be understood independently of one another: the OceanHealth organization is defined by what its active members are working on (TÉTCEN) as much as the things being worked on are (re)defined by OceanHealth. Thus, in terms of the dialectical orientation of CHAT, the subject, which schema are brought to bear, and the relevant object, which material structures are currently relevant, presuppose (determine, constitute) one another (Leont’ev 1978). One commonly used heuristic for understanding human activity includes four additional basic conceptual entities: means of production (including instruments, tools, artifacts, and language), community, division of labor, and rules (Engeström 1987). In Fig. 1, we exemplify this heuristic for the analysis of marine conservation that members of our research group have investigated for 5 years. Again, because of the dialectical orientation of CHAT, none of these six entities can be studied in isolation from one another without loosing its connection with its current (a) material and cultural and (b) historical context that makes up the organization of society.

To understand and theorize any moment of human activity, three concurrent levels of events need to be distinguished: activities, actions, and operations (Leont’ev 1978). In CHAT, actions on objects play a special role, because this is what human individuals bring about and what researchers observe. Making a display, water sampling, or mapping Eelgrass are typical actions, for they realize conscious goals articulated by individual marine conservators. An action implies both physical (bodily) involvement and participation in societal activity (marine conservation). Actions also imply acting subjects and objects acted upon. Actions only make sense with respect to the particular activity, because in a different activity it will have a different sense—using the same equation in engineering or physics realizes different goals, has a different sense, and has different outcomes (Brown et al. 1989). Actions, however, do not constitute the lowest level in the analysis, for goal-directed actions are realized by unconsciously produced and enchained operations.

Figure 1 essentially depicts the structural aspects of human activities and does not lend itself to view its dynamic aspects. Brad, however, was on a trajectory, which inherently is a dynamic phenomenon and experience. When we attempt to understand Brad’s trajectory, we have to take into account that in the course of our research he participated in very different systems of activity—producing and reproducing Aboriginal culture in his family and village, producing environmental knowledge while participating in environmentalism practices at OceanHealth, and gaining an understanding of science while in the water laboratory (Fig. 2).

Cultural–historical activity theory here is an ideal tool for us, as it presupposes entire human activities as its basic unit of analysis: we therefore cannot understand what an individual teacher or student does at some moment in time unless we take into account schooling practices at the particular cultural–historical moment in time. Any student action in the 1950s when one of us first started going to school was very different from what students do today, and therefore, the action possibilities displayed while working on tasks (using slates vs. using computers, doing long-hand division vs. using hand-held calculators). What it means to know in the three communities of practice where Brad was participating in the course of our research and therefore the action possibilities Brad exhibited cannot be understood unless each is considered in its historical context. More so, we can understand his action possibilities only in its own cultural–historical context, which took Brad first from his native village culture to the environmentalist NGO (non-government organization) and then into a scientific laboratory.

Activities are directed towards objects, always formulated and realized by collective entities (community, society). Marine conservation is one such activity; marine conservators can earn a salary, which they use to satisfy their basic and further needs, because marine conservation contributes to the maintenance of society as a whole. That is, in a strong sense even marine conservation cannot be understood on its own but only in the context of other activity systems with which it makes a network that produces society as a whole. Actions are directed towards goals, framed by subjects (individuals, groups); when Brad compiles a display for the floating Nature House, this constitutes an action, because at any time during the day, he makes conscious decisions (forms the goal) to go to the Nature House and to compile a display. Operations are unconscious, determined by the current conditions, for example, the current state of the action and its relation to the social and material structures of the setting that afford the practices he enacts. Brad does not have to form the goal, “glue a picture on the display,” but his arms and hands produce the required movements for gluing the picture on the display.

Our adoption of the notion of practices as human activity has particular consequences for how we understand scientific knowledge. To us, science is a practice in which scientists engage as their profession. While working, they exhibit knowledge in the moment of doing and when they expand their action possibilities, we know that they have learned. As such, we do not see science as a universal way of knowing and understanding the natural world around us. Rather, we regard scientific facts and theories as resources that mediate action and therefore cognition in particular ways. These resources can be used in particular situations and for specific purposes that are deeply bound up with the practices of scientists (van Eijck and Roth 2007). The cultural–historical framework allows us to make sense of Brad’s actions and of the apparently contradictory results emerging from his participation in authentic practice, which led him to change from considering science as a career to rejecting it as a career option. In the process of our research, we observed how in and through his actions, Brad hybridized the differently grounded cultural–historical practices in which he engages (i.e., his traditional ecological knowledge, scientific knowledge). By focusing on the moments of human activity, we can then observe how those practices change, and, simultaneously, how Brad changes and particular choices emerge.

Culture as a mêlée of practices

Brad’s participation in different activity systems does not yet assist us in understanding how actions and identities change when individuals move along trajectories that take them through different communities of practice. That is, the diagram in Fig. 1 only presents the activity systems in which Brad participates at a single point in time. But CHAT has a second focus in the cultural and historical nature of human activity, that is, its aspects as they occur or change over a period of time (Roth and Lee 2007). Thus, these activity systems as a whole and each of its constitutive parts require an understanding of the cultural–historical context. We therefore cannot understand Brad’s particular participation in the practices we sketched above without taking into account Brad’s cultural identity that is both produced by and a product of the practices in which he engages, which in turn can be understood only in the cultural–historical context of growing up as an Aboriginal in a largely ‘Western’ society that is on a very different cultural–historical trajectory than his own ethnic group.

In cultural–historical activity theory, identity is understood as a co-product. This is so because, ever since G. W.·F. Hegel (1977) characterization of the relationship between individual and collective consciousness, actions are understood as resources for attributing character traits to an individual. In activity theory, however, an individual is theorized not only in its relation to others (i.e., community) but also in relation to every other constitutive moment of the system (i.e., tools, rules, division of labor, and object/motive). Because the agential subject is an integral and constitutive part of the system as a whole, a change anywhere in the system, therefore, implies a change in the subject as well, that is, a change in identity.

During the last decade, there is an increasing interest in research that centers on the role of cultural identity in science education. In discussions concerning cultural identity until the 1990s, the term culture generally was used in a rather static way. One example of such as reference to culture (a) as a “theoretically defined category or aspect of social life that must be abstracted out from the complex reality of human existence” or (b) as a “concrete world of beliefs and practices” (Sewell 1999, p. 39, emphasis added). Such notions are rather static because they reduce culture to something that is abstracted from the complex reality of human existence, that is, formalized, and yields a concrete and stable—in some cases even almost palpable—entity in which new members are conceived as ‘newcomers’ who are ‘socialized’ and ‘enculturated’ to it along trajectories that range from peripheral to core participation, at which point they are part of a group of “indigenous” or “Western” people. In contrast, the field of cultural studies of science education has seen many attempts to overcome culture as something that cannot be reduced to concrete or stable categories but that is more fluid and diverse by nature. One recent example is a framework that is drawn upon while revisiting three diverse cultural ways of understanding nature, such as an Indigenous way, a neo-indigenous way, and a Euro American scientific way (Aikenhead and Ogawa 2007). This framework recognizes how understanding cultural identity, as related to different ways of knowing the natural world, requires at least a myriad of multi-layered categories in order to acknowledge the diversity involved. However, as one of us has articulated in response (van Eijck 2007), any category introduced to distinguish between different ways of knowing the natural world inherently introduces another dichotomy that again reduces the cultural diversity involved to static and mutually exclusive categories. Therefore, we find it ourselves useful to draw in this study on a framework we developed previously to overcome the opposition between multiculturalism and universalism in science education (van Eijck and Roth 2007). In this study, we abandoned the concept of “truth.” Rather, we adopted a cultural perspective that treats the sciences and indigenous forms of knowing as human practices rather than as universal ways of knowing. As a practice and its inherent way of knowing, both the sciences and indigenous forms of knowing are examples of the many possible ways by which humans come to understand the natural world around them. Defined in this way, science, as it is commonly practiced in laboratories, is usually both contributing to and produced by Euro-American culture. For this reason, as well as to value indigenous knowledge as a form of human science as well, some authors prefer to refer to forms of knowing such as science practiced in laboratories by referring to particular cultural categories such as “Western science” (e.g., Aikenhead 1997) or “Western Modern Science” (e.g., Snively and Corsiglia 2001). These forms of science are then contrasted with other forms of science such as “native science” or “indigenous science” (e.g., Brayboy and Castagno 2008). However, again, such annotations introduce arbitrary categories we wish to avoid in order to come closer to the fluidity of culture. More so, we agree with scholars who do not think that broadening the concept of science so as to talk about “native science” or “indigenous science” is indeed the best strategy to value other ways of knowing for their own sake, validity, and legitimacy (e.g., El-Hani and Souza de Ferreira Bandeira 2008).

The problematic in this case centers on how to acknowledge that culture is certainly one and almost palpable for people who live their culture and as such contribute to the identity of that culture, while, on the other hand, any categorization or of a culture in stable, formalized, and eternal categories introduces dichotomies that reduce its diversity. Especially the latter has been recognized as problematic for First Nation peoples who found their “culture” locked in museums designed by people from European descent, being forever something from the past that is no longer able to evolve by their being (e.g., Atleo 1991). Our stance, therefore, highlights the dynamic, heterogeneous, and plural nature of human culture, while we simultaneously acknowledge the importance of a cultural identity for individuals and groups. Hence our position is rooted in the position taken by philosophers of difference for this position is commensurable with our own observations and transcultural experiences:

A culture is single and unique….A “culture” is a certain “one.” The fact and law of this “one” cannot be neglected; even less can it be denied in the name of an essentialization of the “mélange.”

But the more this “one” is clearly distinct and distinguished, the less it may be its own pure foundation. Undoubtedly, the task is wholly a matter of not confusing distinction and foundation; in fact this point contains everything that is at stake philosophically, ethically, and politically in what is brewing [se trame] around “identities” and “subjects” of all sorts. Thus the absolute distinction of the ego existo, provided by Descartes, must not be confused with foundation in the purity of a res cogitans, with which it is joined together. For example, the “French” identity today no longer needs to found itself in Vercingétorix or Joan of Arc in order to exist. (Nancy 2000, p. 152)

This notion allows us to grasp the cultural identity of peoples, Aboriginal peoples included, as a dynamic, current process which actually provides identity by its continuous collective being and becoming (ego existo) as opposed to an entity rooted in a static and never-changing (never-existing) pure foundation from an unknown (unlived) past (res cogitans). Following Brad in his native village, we observe the Nation using “Western” tools (Internet, cars, etc.) but also staying (attempting to stay) in touch with traditional technology and knowledge systems. In this way, Brad’s root culture already cannot be thought as “one,” but only as a mêlée of cultural practices that continually transforms itself through further hybridization, which occurs when Brad, after participating in other cultural systems, returns as a changed subject, introducing new cultural elements into his village. Some science educators feel that “the separation between traditional and modern cultures is eroding as each finds a place in today’s cultural and economic practices” (Gaskell 2003, p. 235). From our perspective rooted in a philosophy of difference, cultures always hybridize each other and themselves. In this sense, culture has a dynamic and collective rather than a static and individual nature. Thus, although the culture of Brad’s Nation is surely one, it is also in a continual state of mixing with (but not disappearing in) “Western” society. Rather than to perceive culture as a mélange, therefore, “it would be better, then, to speak of mêlée: an action rather than a substance” (Nancy 2000, p. 150), which continually produces and reproduces difference, heterogeneity, and hybridity (Roth 2008). This allows us to understand Brad’s cultural identity as “a ‘production’ which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation” (Hall 1990, p. 222). As such, Brad’s path is part of a continual process that we denote as mêlée in and by means of which individuals produce cultural identity in and through their participation in practices and hence their contribution to changes in practices. The notion of a mêlée of practices also implies a continuous movement between the moments of activity. Objects may be transformed into outcomes, and then turned into tools, and perhaps later into a rule. For instance, nature conservators may work on a polluted marine habitat (object), which can be turned by means of research into data (tools), eventually underpinning environmental policy measures (rules).

Departing from the notion of a mêlée of practices, this study, as an account of culture, should also be perceived as such. In conducting our ethnography, we started as relative outsiders, neither being environmentalists nor First Nations people and hence inexperienced with the practices of OceanHealth and the First Nations community of which Brad was part. In turn, both the leader of OceanHealth and Brad were inexperienced with educational research and the practices of which we were part in this respect. Therefore, initial interviews with Brad and the leader of OceanHealth were plagued by mutual insider–outsider experiences; at times we were each hesitant, defensive, and careful, as is natural in growing human relationships. This also counted for our observations, which were initially of an outsider. However, gradually, during our year-long engagement in practices in which Brad also participated, we came to understand why he made the choices he made and he came to understood why we setup the internships collectively and followed him throughout. What was initially our study became a collective enterprise in which both Brad and the leader of OceanHealth had critical voices too. Interviews turned into conversations and observations became introspective. The study became a collective one in which roles of both researchers and participants could not be attributed to particular persons anymore.

Prior to submitting this paper about our study, we provided Brad and the leader of OceanHealth the opportunity to review and comment on our interpretations. They were both fine with the paper assuring that it reflects the practices in which we engaged collectively and which were ultimately built on mutual respect and trust. Thus, this paper should be seen as an account of the mêlée of practices we established by a year-long ethnography through which we all became insiders in a joint practice that cannot be denoted by either one of our initial practices in which we each participated (educational research, environmentalism, First Nations community).

Merging and changing practices through participation

In the remainder of this paper, we use the theoretical position of the mêlée of practices developed thus far to examine, in detail, the ways in which Brad hybridized the various mundane and scientific practices that intersected in and through his participation. As such, we show how our case study reveals changes in Brad’s orientation towards science and his career choices as a result of hybridization of practices.

Issues of cultural identity in/of First Nations communities from the Pacific Northwest

We start by providing some salient contextual detail about Brad’s background and the issue of cultural identity in/of the native community of which he is part. This detail serves as an essential backdrop for understanding how and why Brad engaged in the various mundane and scientific practices that intersected in and through his participation.

Each band has its own unique history, but in several respects, Brad’s community is not unlike many other First Nations communities in the Pacific Northwest of Canada. These communities have undergone a series of serious cultural changes since the 1850s when the Europeans set in motion the colonization of this part of the world. Either by means of treaties or not, First peoples were forced to live on reservations where starvation and foreign diseases such as smallpox decimated their population. This is not only something from the far past—some diseases such as tuberculosis infected communities well into the 1950s. In addition, between 1879 and 1986, many Indigenous children in Canada were forcibly removed from their communities by the authorities and placed into residential schools. Parents were forbidden to visit their children, and the children were prevented from returning home. As a result, many aspects of their unique culture disappeared or became strongly mediated by a foreign European identity. As well, First Nations communities were faced with many laws by which unique features of their culture and economy were outlawed, such as particular fishing technologies and ceremonial feasts. Because the First Nations culture was severely affected by deliberate government actions, this process is often described as a “cultural genocide.” Indeed, all Salishan languages are now endangered—some extremely so with only two speakers left—or extinct (Moseley 2007).

As a result of the colonization, many communities lost control over productive resources and self-determination and slid from independence and self-sufficiency to dependency, underdevelopment, poverty, and, most importantly, little or no control over education and cultural development. As one First Nations participant in our study put it: “We were once a proud nation and see what is left of it today.” This awareness of the current situation, which is actually one of despair, is typical for a renaissance that is going on in First Nations communities. This renaissance should not be confused with the renewed interest for First Nations cultural heritage currently observable in museums; these representations often being objects for critique by First Nations people as spiritless and rooted in colonialism (e.g., Atleo 1991). Rather, the renaissance is a cultural revival that follows from growing populations and a growing sense of self-determination. Many people like Brad are actively busy with defining their current cultural identity and development. Hence they are usually rather keen on activities that have to do with their cultural identity. For instance, Brad told us that he was aware of an academic project of a fellow band member who attempted restoring and rebuilding once outlawed but highly sophisticated fishing technologies. In this vein, Brad himself was very interested in First Nations ethnobotanical knowledge as a means to better understand the native natural environment. More so, he engaged in the practice of environmentalism in order to take responsibility of TÉTCEN, a sacred but abandoned place his community belonged to but that was affected by the “White men’s” actions. This choice is unique, for he told us that other band members did not feel like taking responsibility for the havoc the White men had created in this place. At the tribal school in the community, where initially Brad and our paths merged, the revival of First Nations culture was also celebrated. For instance, at the time we were working with Brad, we witnessed several developments towards forms of education that met the needs of and were initiated by First Nations people. As we will show in more detail, Brad became involved in one of these developments as well.

The renaissance should not be perceived as a sign that in communities like that of Brad’s everything is going strong now. On the contrary, the people in Brad’s community are still confronted, almost on a daily basis, with real problems they encounter as a result of the current confused and relatively powerless state of their Nation. For instance, during the relatively short period of time we worked with Brad (about a year), we witnessed two cases of how the community was severely treated. In one case, the entire community got upset because one of its most sacred places was defiled by a constructing company developing real estate nearby. In the other case, the entire community engaged in Native activism and organized a protest meeting at the provincial government building in order to defend its titles to productive resources supposedly enacted in a treaty. These problems, resulting in confusion and insecurity, are taking place both at the communal and individual level. Typically for the latter, Brad once pointed out that he did not want his Nation to end up as a “footnote in history”.

In short, the current state of many First Nations communities such as the one from which Brad came, can be perceived as a confusion of identity which raises questions about their existence. However, it would be inappropriate to finish the description here; so far we framed and therewith silenced the First Nations identity by describing it rather by our “Western” academic voices. Therefore, in order to provide essential contextual detail and hence to contribute to an appropriate understanding of why people like Brad make the choices they make and thus engage in practices that intersect in and through their participation, we want to conclude this paragraph with featuring a First Nations voice. Indeed, unlike the common “Western” academic genre, this understanding is perhaps best expressed with a poem featured as part of the foreword of a seminal academic book about the current cultural revival of the First Nations of British Columbia, called “In Celebration of Our Survival:”

Our Voice — Our Struggle

We are struggling to find our voice,

The right tone, the right pitch,

The right speed, the right code

The right thoughts, the right words

We are struggling to find the voice,

To say how long we’ve waited to speak,

To say we’re tired of waiting so long,

To we’re tired — and frustrated

Struggling, we wax nostalgic,

Struggling for a new reading of history,

Struggling for human status,

Struggling just to be heard.

We are struggling against false accusations.

(Hamilton 1991)

Native plant expertise as a tool in nature conservation and native activism

The opening vignette of this paper glosses how Brad engaged in the practice of nature conservation. His actions commonly focused on objects in local ecosystems, such as monitoring the water quality of marine habitats and creeks in the surrounding watersheds and mapping Eelgrass (Zostera marina), a native plant once abundant in local marine habitats. He also engaged in attempts to engage the wider community in this practice. For instance, in TÉTCEN, OceanHealth maintained a floating Nature House, which is a stewardship and information centre for citizens from the local community and seasonal marine recreants. There, he compiled a display about a First Nations perspective on TÉTCEN. As well, he assisted in getting local schools involved by giving tours to school children in watersheds surrounding the local marine habitats. Through his internship in OceanHealth, Brad contributed in many different ways (actions) to the practice of nature conservation in his aboriginal community specifically and in the wider community (municipality) more generally.

Following Brad around, we could immediately see that he brought into practice a tremendous amount of native plants expertise. Because of its value for nature conservation, Brad was encouraged to enact this expertise in the service of his work for OceanHealth. As such, this expertise mediated actions to the practice of nature conservation, such as invasive plant removal, salvaging, harvesting, and replanting of native plants and leading ethnobotanical tour for school children. This particular mediation was important for Brad because it concretized possibilities that produced his cultural identity as an Aboriginal. For Brad, this work was not just a matter of nature conservation focusing on a marine habitat that was dramatically affected by the past and present activities of the rapidly increasing population surrounding his reservation. Rather, what got Brad really involved was the focus of OceanHealth on TÉTCEN. This inlet once was a major marine harvesting ground his people belonged to, where they had come to collect clams, oysters, and mussels as long as their individual and story-based collective memories reach into the past. As such, this was a sacred place and deeply bound up with his people’s identity. For Brad, being and working with this place was bound up with the restoration and conservation of his own cultural identity and that of his people. As such, nature conservation intersected with the native activism he engaged in as a band member and this intersection is one account of the many ways by which Brad realized his cultural identity as a mêlée of different practices.

His contributions (actions) to the practice of OceanHealth mediated by his expertise of native plants were highly appreciated by the other community members of OceanHealth. For instance, in an interview Brad told us:

Yeah. Yeah, they actually even… umm… took a piece of my, well… not a piece of my knowledge but a knowledge I shared with them about… about a plant that… that I… that I was told can help against preventing flying insects from flying in the house. They actually harvested some of those plants and put it downstairs so… I felt… I felt… umm… really honored that… that… that they did that. That they were practicing my practices. That they were practicing my… my… umm… culture, if you will.

In this example, we can observe how Brad articulates how his actions contributed not only to the general (societal) motive realized by the OceanHealth organization, but as well, in return, his participation in the practice of OceanHealth encouraged him to realize his cultural identity by merging nature conservation with the practice of native activism.

Brad’s actions mediated by his native plant expertise were not only appreciated, and led to merging the practice of OceanHealth with native activism. Rather, as a result, due to this hybridization of practices new possibilities emerged by which several practices of OceanHealth changed. For instance, as a result of Brad’s ethnobotanical tours, teachings to students focused more than they previously had on traditional uses and characteristics of the land surrounding the marine habitat. As such, Brad enacted forms of expertise not previously available to and observable in the OceanHealth context. Thus, new activity-orienting objects were created for OceanHealth, such as teaching school children about First Nations uses of the land. This change in the object of the activity, because of its constitutive place in the activity as a whole, is an indication that the activity has changed.

In short, enacting native plant expertise, his actions in the context of and intelligible in the OceanHealth activity system, Brad hybridized practices of nature conservation and native activism simultaneously. His traditional ecological knowledge and the “Western” knowledge on which OceanHealth was based came to hybridize each other. And in this hybridization of his practices, he also enacted a hybridized cultural identity.

Scientific practice as a tool in nature conservation

During the internship, Brad experienced how scientific tools mediated the practice of nature conservation. These tools were commonly available and applied within OceanHealth, such as the various instruments to measure water quality. As any tool within an activity system, these scientific tools therefore mediated Brad’s actions in nature conservation as well. However, as contributions to the practice of OceanHealth, these actions were rather limited. That is, to a lesser extent than his native expertise, the scientific tools mediated actions that led to the emergence of new objects and tools in the nature conservation practice of OceanHealth. For instance, Brad monitored the water quality of several creeks by a number of standard procedures such as colorimetric measurements of effluents (e.g., phosphates), and oxygen and temperature measurements. However, the outcomes of these measurements were collected, processed and analyzed by the regional government and Brad had no further access to the procedures and the resulting data. As well, the scientific tools used by OceanHealth did not change by Brad’s actions. He did not bring in new or modified existing scientific tools. The actions that were mediated by scientific tools thusly did not change by means of his engagement.

During the drinking water laboratory internships, Brad and the other student collected the samples and brought them to the laboratory for analysis. The main technician prepared and processed the samples and conducted the various analyses, thereby explaining every action in great detail and giving Brad the opportunity to closely follow the path which the samples followed through the laboratory to generate data. In a sense, he was able to do precisely what it takes to understand science and engineering: follow pieces of materials and the transcriptions that they are converted into along their trajectory through scientific institutions (Latour 1987). Brad therefore was precisely in the same situation as anthropologists trying to understand science, with the similar result that he came to better understand the science involved. Brad repeatedly asked questions and discussed the various steps with the technicians and showed tremendous interest in the technicians’ actions. After having been in the laboratory for several days with a technician, the desired data about his native place (TÉTCEN) were finally generated. By engaging in the internship in the laboratory, Brad thereby witnessed in detail how scientific tools can mediate the practice of marine conservation. For instance, he observed a number of tools that were applied to provide data about toxic substances in the samples of marine animals he collected, including a sample concentrator and a gas chromatograph. After having observed in detail this process, Brad told us: “I feel educated. In the sense that ah, I got to see and understand the processes that, that go on to figure out what pesticides are in the sample that we provided.”

However, despite his sense of having been educated, Brad contributed to the actual science done in only limited ways. He was more of a participant observer than an observer participant central to the anthropologists’ method of learning about a culture through apprenticeship (Coy 1989). To begin with, because Brad could not enact the appropriate level of laboratory-relevant expertise and skills, the technician could not provide him with the opportunity to handle the instruments that mediated the actions in this practice. In the time frame of the internship (3 days), the technician explained that “a proper training which takes a month in this case is not a reality.” As such, Brad was only in the position to observe the scientific actions in the laboratory. He was not allowed to participate in scientific practice to the extent that he also could perform actions mediated by scientific tools by himself. As a result, Brad did not significantly contribute to scientific practice by performing actions in the laboratory.

The outcome of the scientific practice consisted of the data that indicated the amount of pesticides in the marine animals and sediments. These data, as a result of the internship in the laboratory, mediated Brad’s further actions and thus became tools in marine conservation. However, by the time, it appeared that this tool was rather limited and costly as a mediator of the practice of nature conservation. Brad learned that the water quality data, of which he witnessed and helped the emergence during the internships, were inadequate from the perspective of government policy makers. Indeed, there would be no extra support for restoration of the area he was working on. As the nature conservation internship supervisor put it:

[The regional government] was saying, you’ve got to have eight replicates before we can make a story out of this. You mean we have an eighth of a story worth thousands of dollars, lots of time. … And what I wanted was a clear, progressive way to move forward. And we’re not getting that from the lab. That’s my, that’s my take. And the scientific method is complex, which is fine. It is. It’s complex. But the resources don’t match the complexity. So, for us to go look for more funds to get the lab to help us, eight more times—we’re looking at $10,000—before other agencies will tell us this story.

In short, rather than actually engaging in scientific practice and therewith contributing to it by doing actions mediated by scientific tools, Brad only contributed to scientific practice through bringing the samples and interacting with laboratory staff. As a result, the scientific practice did not change observably and, through Brad’s participation, merged to a limited extent with the practice of nature conservation. The outcome of scientific practice, the data, became rather a tool in the nature conservation practices in which Brad engaged at the time and as a tool, the data appeared to be limited in mediating nature conservation. Here, then, we can observe another an account of the intersection of several practices through Brad’s mutual participation by which he realized his cultural identity as a mêlée of different practices. However, only as a tool with a limited impact on the other practices in which Brad participated, as such, scientific practice intersected in a rather limited fashion with the practices in which Brad engaged and by which he realized his cultural identity as a mêlée of different practices.

Changing orientation to science

The interviews with Brad prior and during the start of the nature conservation internships revealed that his orientation to the practice of science was generally positive. For instance, during the Possible Selves interviews, Brad told us:

Umm… in general I think being a scientist is a good career because… and then… because you can, you can teach… other people about… about what you’re doing with your science, right? And… you know… share it, like just share it with the general public and not have it in that academic setting like in school or whatever.

For Brad, the possibility of teaching and sharing “your science” with the general public rather than keeping it in a school-like academic setting is what makes science a good career. As well, he articulates science here as something that he possibly can call his own and something that is sufficiently important to share with the general public. As such, Brad articulates science as a possible part of his identity to be shared with others.

With respect to his interest in science and the reasons for which it should be shared, Brad later expressed:

I found it [science] fascinating because it’s actually showing evidence that… uhh… umm… man is affecting the water quality. And the water quality seems to be going down. To me, to me it seems like it’s getting more polluted. That’s my opinion.

Here, Brad frames science as that of a practice that is “actually showing evidence” And which can be used for nature conservation. Here, Brad is envisioning science to be valuable in its intersection with another practice he was about to engage at the time, namely nature conservation.

Brad’s initial orientation to science changed in a way that is intelligible in regard to his specific engagement in both the practices of nature conservation and science during the internships which we outlined previously. Following the lab internships, Brad told us about the evidence:

We should learn how to talk to the general public so that, that, that we can get, get our message across. To, to the general public not, and make it in such a form that, that, that this data we’re representing to them isn’t us wagging our finger at them. It’s us presenting this data to them, asking them for their help, and to come on board and become part of the solution rather than part of the problems. Um, sorry to use such.

Instead of a practice that is a possible part of his identity to be shared with others, Brad articulates here a more instrumental view of science as he experienced it through his participation in the lab internships. For instance, rather than “actually showing evidence that man[sic] is affecting the water quality,” he acknowledged that evidence is actually composed of “data” and “talking more scientific.” Yet, Brad indicated that his engagement in science was fruitful in the sense that he experienced how the practice of science is tied with other practices one requires to get things accomplished in nature conservation:

On, on needing those connections to know who, who to go to, and who’s full of themselves because they have this fancy title within this organization and they get, they get appointed this, this, this power that gives them the right to say who’s, who has won, and who’s data is right and applicable to, ah, what industry or whatever. If it’s like for conservation work like what we’re doing and monitoring of that stream.

As such, the engagement in scientific practice through the internships empowered Brad by experiencing how science is of value as an instrument that mediates the practice of nature conservation. However, due to these experiences, Brad also approached science as a limited tool in practices to which he contributed and that changed due to his participation. Indeed, science contributed to nature conservation as data that can be used to convince others, but Brad himself did not contribute to the practice of science by realizing new possibilities through his participation.

Besides a shift towards a more instrumental view of science, there was also another change in Brad’s orientation to science, which had to do with the realization of his cultural identity as a mêlée of different practices. After the internships, we recognized that the contribution of the practice of science to his identity was limited because of epistemological differences. It appeared to us that doing science was of a lesser value to him than, for example, nature conservation and native activism, because the scientific method that he experienced in the laboratory tends to discount the complexity of the environment as he has come to know it through his culture and through experiencing it in the local environment:

Yah. Yah, they’re just taking it apart too much rather than um, leaving it as a whole picture. And then taking out, teasing out the odd little parts and putting it back so that you still have the whole picture. Rather than this whole line of little pictures. That don’t really make up anything. Except for a bunch of little pictures. Rather than the whole picture, and something that’s, that’s, that’s complete. Yah, they just analyze too much. They overanalyze a lot of things.

Brad thus expected the scientific way of approaching environmental problems to limit his possible future actions, which he sees enhanced by his aboriginal epistemological commitment of understanding of and caring for the environment:

Yah. Because that’s essentially what it is. It’s a box. You’re in a box, the building, the room, it’s a box. The testing that you’re doing, it’s on a square table, that’s a box. When you’re working with the chemicals in a hood, it’s a box. You’re boxing yourself up.

In short, Brad recognized that the science experiences had empowered him. Yet, he considered the sciences as too limited a tool to mediate actions that contribute to his cultural identity such as nature conservation, and as such the contribution to the mêlée of different practices which makes up his cultural identity as an aboriginal is also limited. More so, he no longer considered the practice of nature conservation as being a scientific practice per se. This changed his orientation to science, which changed from generally positive to mixed. In contrast, his career aims changed from more or less undecided to a true dedication.

Changing role of science in career aspirations

Upon entering the internship program, Brad was not yet certain of what his future career should be. Brad started the internship because he was interested in the nature conservation part of our program and he wanted us to share that with him so that he could learn from us. As well, at the time, he had a number of possible selves in mind, such as that of a native plant nursery owner, an ethnobotany teacher or a nature conservator. However, as he explained later, at the time, he did not pursue such possible selves yet:

Um, I wasn’t really in, in, in ah, conversation type setting, or set, set of mind. And, um, I was more, more into just greenery; any kind of greenery was good. Um, but, yah, I think that was a key moment in the last year was starting here and changing that, that, that, changing my point of view from any kind of greenery is good to the native greenery to this region is best. And, I think that um, that’s something that, that I’ve been really trying to learn more and appreciate more. Um, get more people on board to, to appreciate all this, all this um, native beauty that’s from our region.