Abstract

By integrating policy regimes and campaign theories, this article investigates the institutional mode by which China’s local governments transcend their structural-interest constraints and overcome their capacity deficits to successfully implement targeted poverty alleviation (TPA) policies. Using a “campaign-style implementation regime” framework and three counties as cases, we analyzed and coded the institutional structures, elements, and mechanisms for achieving the counties’ TPA goals. First, the case study indicates that the campaign redistributed local political attention and became the “idea glue” for policy integration. Second, through the campaign, horizontal and vertical, formal and informal, institutional arrangements were constructed to redistribute decision-making power, and coordination mechanisms were built within the Tiao/Kuai system. Third, the campaign constructed complex interest-alignment mechanisms within the political system, involving many actors and changing their motivational structures. In addition, we found that the campaign-style implementation regime was achieved through local governments’ institutional reintegration and recombination between structures and actors. Theoretically, the campaign-style implementation regime provides a new analytical perspective on the dynamics of regime construction and the institutional elements within a campaign. Practically, it offers an escape route for developing countries ensnared in a capacity trap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

< Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution > , The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, April 2021. Available online, http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/32832/Document/1701632/1701632.htm (accessed September 13, 2021).

Regime theory originates from international relations [25] and urban governance [6]. Regime is also an important concept in the study of policy processes (e.g., [48, 56]). The policy implementation regime theory is an integration of these basic concepts. It provides theoretical guidance for opening the black box of a policy system.

The main goal for TPA was for 56.3 million poor residents in rural China (2015) to obtain “one ‘have’, two ‘non-worries’, and three ‘guarantees’” (liang bu chou, san baozhang 两不愁三保障) by 2020. Specifically, every poor rural resident would have a stable income of 4,000 yuan per year (one “have”), enough food and clothing to live on (two “non-worries”), and adequate access to compulsory education, basic medical care, and housing (three “guarantees”). To be considered lifted out of poverty, the county government had to meet the “three ‘rates’ and one ‘degree’” (san lv yi du 三率一度) standard. “Three rates” refers to the target rates for the incidence of poverty (< 2%), the rate of missed targeting (< 1%), and the rate of wrongful removal from the poor households list (< 2%). “One rate” refers to the public satisfaction rate (> 90%). All three counties met the “three ‘rates’ and one ‘degree’” standard, so we coded them as achieving TPA’s policy goal.

“Double leaders” refers to the poverty alleviation headquarters set up the Party secretary and the head of the county government as two leaders.

“Five secretaries” refer to the five secretaries of the CPC Central Committee, the Provincial Party Committee, the Municipal Party Committee, the County Party Committee, and the Village Party Committee.

It means that Party members and cadres are mobilized to help the rural poor, just as they would help their own relatives.

“Danwei” is a special organization based on China’s socialist political system and its traditional planned economy system. It provides a variety of functions such as political control, professional division of labor, and living guarantees. Currently, the term Danwei mainly refers to all public institutions within the Party-state. The typical form of an urban Danwei includes the Party and government institutions (xingzheng Danwei 行政单位), state-owned management and service institutions (shiye Danwei 事业单位), and SOEs.

References

Ahlers, Anna L., and Gunter Schubert. 2010. “Building a new socialist countryside”–only a political slogan? Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 38 (4): 35–62.

Cai, Changkun, Qiyao Shen, and Na. Tang. 2022. Do visiting monks give better sermons? “Street-level bureaucrats from higher-up” in targeted poverty alleviation in China. Public Administration and Development 42 (1): 55–71.

Cai, Changkun, Weiqi Jiang, and Na. Tang. 2021. Campaign-style crisis regime: How China responded to the shock of COVID-19. Policy Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2021.1883576.

Cai, Changkun, Yuexiao Li, and Na. Tang. 2022. Politicalized empowered learning and complex policy implementation: Targeted poverty alleviation in China’s county governments. Social Policy and Administration. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12802.

Chen, An. 2014. How has the abolition of agricultural taxes transformed village governance in China? Evidence from agricultural regions. The China Quarterly 219: 715–735.

Davies, Jonathan S. 2002. Urban regime theory: A normative-empirical critique. Journal of Urban Affairs 24 (1): 1–17.

Deng, Yanhua, Kevin J. O’Brien, and Jiajian Chen. 2018. Enthusiastic policy implementation and its aftermath: The sudden expansion and contraction of China’s microfinance for women programme. The China Quarterly 234: 506–526.

Deng, Yanhua, Yingyi Wang, and Wei Liu. 2020. New mechanism for poverty alleviation: Organization, operation, and function of work teams stationed in villages [in Chinese]. Sociological Studies 35 (06): 44–66.

Ding, Jianbiao. 2020. Research on the practice process of rural poverty alleviation in China from the perspective of holistic governance [in Chinese]. CASS Journal of Political Science 03: 113–124.

Feng, Shizheng. 2011. The formation and variation of the Chinese state campaign: A holistic explanation based on the polity [in Chinese]. Open Times 01: 73–97.

Fu, Xiaxian, and Zuhui Huang. 2021. Institutional advantages manifested in China’s poverty eradication and the implications for the world [in Chinese]. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 51 (02): 5–14.

Gao, Hong, and Adam Tyson. 2020. Poverty relief in China: A comparative analysis of kinship contracts in four provinces. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (126): 901–915.

Gieve, John, and Colin Provost. 2012. Ideas and coordination in policymaking: The financial crisis of 2007–2009. Governance 25 (1): 61–77.

Grindle, Merilee S. 2004. Good enough governance: Poverty reduction and reform in developing countries. Governance 17 (4): 525–548.

Han, Huawei, and Qin Gao. 2019. Community-based welfare targeting and political elite capture: Evidence from rural China. World Development 115: 145–159.

Hill, Michael, and Peter Hupe. 2006. Analysing policy processes as multiple governance: Accountability in social policy. Policy & Politics 34 (3): 557–573.

Howlett, Michael, and Jeremy Rayner. 2013. Patching vs packaging in policy formulation: Assessing policy portfolio design. Politics and Governance 1 (2): 170–182.

Huang, Xian. 2015. Four worlds of welfare: Understanding subnational variation in Chinese social health insurance. The China Quarterly 222: 449–474.

Jindra, Christoph, and Ana Vaz. 2019. Good governance and multidimensional poverty: A comparative analysis of 71 countries. Governance 32 (4): 657–675.

Jochim, Ashley E., and Peter J. May. 2010. Beyond subsystems: Policy regimes and governance. Policy Studies Journal 38 (2): 303–327.

Kautz, Carolin. 2020. Power struggle or strengthening the party: Perspectives on Xi Jinping’s anticorruption campaign. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25 (3): 501–511.

Kennedy, John James. 2007. From the tax-for-fee reform to the abolition of agricultural taxes: The impact on township governments in north-west China. The China Quarterly 189: 43–59.

Kennedy, John James, and Dan Chen. 2018. State capacity and cadre mobilization in China: The elasticity of policy implementation. Journal of Contemporary China 27 (111): 393–405.

Kostka, Genia, and Arthur P.J.. Mol. 2013. Implementation and participation in China’s local environmental politics: Challenges and innovations. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 15 (1): 3–16.

Krasner, Stephen D. 1982. Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables. International Organization 36 (2): 185–205.

Li, Dayu, Changping Zhang, and Xu. Lu. 2017. Precision governance: Transformation of government governance paradigm in China [in Chinese]. Journal of Public Management 14 (1): 1–13.

Li, Mianguan. 2021. The grassroots subcontracting system of Targeted Poverty Alleviation—Administrative mobilization under the squeezing situation [in Chinese]. Chinese Public Administration 3: 62–69.

Li, Mengyao, and Wu. Zemin. 2021. Power and poverty in China: Why some counties perform better in poverty alleviation? Journal of Chinese Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09765-0.

Li, Xiaoyun, and Xu. Jin. 2020. Eradicating absolute poverty: A sociological study of China’s new practice of poverty alleviation [in Chinese]. Sociological Studies 35 (6): 20–43.

Lin, Wanlong, and Christine Wong. 2012. Are Beijing’s equalization policies reaching the poor? An analysis of direct subsidies under the “Three Rurals” (Sannong). The China Journal 67: 23–46.

Liu, Chang, and Guangrong Ma. 2019. Are place-based policies always a blessing? Evidence from China’s national poor county programme. The Journal of Development Studies 55 (7): 1603–1615.

Liu, Mingyue, Xiaolong Feng, Sangui Wang, and Huanguang Qiu. 2020. China’s poverty alleviation over the last 40 years: Successes and challenges. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 64 (1): 209–228.

Liu, Nicole Ning, Carlos Wing-Hung. Lo, Xueyong Zhan, and Wei Wang. 2015. Campaign-style enforcement and regulatory compliance. Public Administration Review 75 (1): 85–95.

Liu, Nicole Ning, Shui-Yan. Tang, Xueyong Zhan, and Carlos Wing-Hung. Lo. 2018. Political commitment, policy ambiguity, and corporate environmental practices. Policy Studies Journal 46 (1): 190–214.

Liu, Zhipeng, and Lili Liu. 2020. The “policy implementation” behind “cadres sent-down the village”—Based on the cadres interaction perspective in China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation Program [in Chinese]. Chinese Public Administration 12: 112–119.

Looney, Kristen E. 2015. China’s campaign to build a new socialist countryside: Village modernization, peasant councils, and the Ganzhou model of rural development. The China Quarterly 224: 909–932.

Lu, Shuang, Yi-Ting. Lin, Juliann H. Vikse, and Chien-Chung. Huang. 2013. Effectiveness of social welfare programmes on poverty reduction and income inequality in China. Journal of Asian Public Policy 6 (3): 277–291.

May, Peter J. 2015. Implementation failures revisited: Policy regime perspectives. Public Policy and Administration 30 (3–4): 277–299.

May, Peter J., and Ashley E. Jochim. 2013. Policy regime perspectives: Policies, politics, and governing. Policy Studies Journal 41 (3): 426–452.

May, Peter J., Ashley E. Jochim, and Joshua Sapotichne. 2011. Constructing homeland security: An anemic policy regime. Policy Studies Journal 39 (2): 285–307.

Mok, Ka Ho., and Jiwei Qian. 2019. A new welfare regime in the making? Paternalistic welfare pragmatism in China. Journal of European Social Policy 29 (1): 100–114.

Mok, Ka Ho., Stefan Kühner, and Genghua Huang. 2017. The productivist construction of selective welfare pragmatism in China. Social Policy & Administration 51 (6): 876–897.

Mok, Ka Ho., and Wu. Xiao Fang. 2013. Dual decentralization in China’s transitional economy: Welfare regionalism and policy implications for central-local relationship. Policy and Society 32 (1): 61–75.

Moulton, Stephanie, and Jodi R. Sandfort. 2017. The strategic action field framework for policy implementation research: The strategic action field framework. Policy Studies Journal 45 (1): 144–169.

O’Brien, Kevin J., and Lianjiang Li. 1999. Selective policy implementation in rural China. Comparative Politics 31 (2): 167–186.

Orren, Karen, and Stephen Skowronek. 1998. Regimes and regime building in American government: A review of literature on the 1940s. Political Science Quarterly 113 (4): 689–690.

Perry, Elizabeth J. 2011. From mass campaigns to managed campaigns: “constructing a new socialist countryside.” In Mao’s invisible hand: The political foundations of adaptive governance in China, ed. Sebastian Heilmann and Elizabeth J. Perry, 30–61. Harvard University Press.

Peters, B. Guy. 2014. Implementation structures as institutions. Public Policy and Administration 29 (2): 131–144.

Pritchett, Lant, Michael Woolcock, and Matt Andrews. 2013. Looking like a state: Techniques of persistent failure in state capability for implementation. The Journal of Development Studies 49 (1): 1–18.

Qian, Jiwei, and Ka Ho. Mok. 2016. Dual decentralization and fragmented authoritarianism in governance: Crowding out among social programmes in China. Public Administration and Development 36 (3): 185–197.

Ratigan, Kerry. 2017. Disaggregating the developing welfare state: Provincial social policy regimes in China. World Development 98: 467–484.

Rosenberg, Lior. 2015. Why do local officials bet on the strong? Drawing lessons from China’s village redevelopment program. The China Journal 74: 18–42.

Rothstein, Bo. 2015. The Chinese paradox of high growth and low quality of government: The cadre organization meets Max Weber. Governance 28 (4): 533–548.

Rothstein, Bo., and Jan Teorell. 2008. What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance 21 (2): 165–190.

Si, Yutong. 2020. Implementing targeted poverty alleviation: A policy implementation typology. Journal of Chinese Governance 5 (4): 439–454.

Stoker, Robert P. 1989. A regime framework for implementation analysis: Cooperation and reconciliation of federalist imperatives. Review of Policy Research 9 (1): 29–49.

Tan, Qiushan. 2010. Why village election has not much improved village governance. Journal of Chinese Political Science 15 (2): 153–167.

Tsai, Wen-Hsuan., and Xingmiu Liao. 2020. Mobilizing cadre incentives in policy implementation: Poverty alleviation in a Chinese county. China Information 34 (1): 45–67.

Waldron, Scott, Colin Brown, and John Longworth. 2006. State sector reform and agriculture in China. The China Quarterly 186: 277–294.

Wang, Chenxi. 2021. Legal and political practices in China’s central-local dynamics. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 14 (4): 523–547.

Wang, Yulei, and Su. Yang. 2020. How to achieve the miracle of China’s poverty alleviation: The precise administrative mode of China’s poverty alleviation and national governance system foundation [in Chinese]. Management World 04: 195–208.

Wei, Xiaojiang. 2019. The mentality of “seeking poverty” of the masses in Targeted Poverty Alleviation and its emotional governance [in Chinese]. Chinese Public Administration 07: 72–76.

Xu, Mingqiang. 2021. How does the headquarters command? Organizational transformation and policy implementation of local governments in Targeted Poverty Alleviation [in Chinese]. Comparative Economic & Social Systems 4: 108–118.

Yan. Jirong. 2020. Anti-poverty and state governance: The innovation significance of China’s poverty-alleviation [in Chinese]. Management World 36 (4): 209–220.

Yang, Jidong, Chuanchuan Zhang, and Kai Liu. 2020. Income inequality and civil disorder: Evidence from China. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (125): 680–697.

Yee, Wai-Hang., Shui-Yan. Tang, and Carlos Wing-Hung. Lo. 2016. Regulatory compliance when the rule of law is weak: Evidence from China’s environmental reform. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (1): 95–112.

Zeng, Qingjie. 2020. Managed campaign and bureaucratic institutions in China: Evidence from the Targeted Poverty Alleviation Program. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (123): 400–415.

Zheng, Yongnian. 2010. Society must be defended: Reform, openness, and social policy in China. Journal of Contemporary China 19 (67): 799–818.

Zhou, Xueguang. 2011. Authoritative regimes and effective governance: The institutional logic of state governance in contemporary China [in Chinese]. Open Times 10: 67–85.

Zhou, Xueguang. 2012. Campaign-based governance mechanisms: Rethinking the institutional logic of Chinese state governance [in Chinese]. Open Times 09: 105–125.

Zhou, Xueguang, and Hong Lian. 2011. Bureaucratic bargaining in the Chinese government: The case of environmental policy implementation [in Chinese]. Social Sciences in China 05: 80–96.

Zhu, Demi, and Shuai Cao. 2020. Decision-making and risk sources: Key to source governance for social stability. Chinese Political Science Review 5 (1): 95–110.

Zhu, Tianyi, and Lijuan Gao. 2016. Research on the link of rural governance elite between state and society under the background of Precise Poverty Alleviation [in Chinese]. Socialism Studies 5: 89–99.

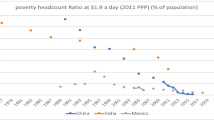

Zuo, Cai Vera. 2021. Integrating devolution with centralization: A comparison of poverty alleviation programs in India, Mexico, and China. Journal of Chinese Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09760-5.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our interviewees for their selfless cooperation in this research, and Qiyao Shen for her help in the process of data collection and processing. This research was supported by National Social Science Fund for Young Scholars of China (17CGL053), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72104084), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2022WKYXZX007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, C., Tang, N. China’s Campaign-Style Implementation Regime: How is “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” being achieved locally?. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 28, 645–669 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-022-09823-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-022-09823-1