Abstract

Eliminating poverty is a worldwide problem, but China has recently made major achievements in poverty alleviation. By the end of 2020, 832 nationally designated poor counties had all been lifted out of poverty within five years. Why do some poor counties perform better in poverty alleviation? This paper leverages a unique county-level dataset of 832 nationally designated poor counties in China and uses discrete-time event history analysis to understand the relationship between political institutions and poverty alleviation. We find that the presence of a county party committee secretary concurrently holding a higher rank position above the county level significantly increases the odds ratio of accomplishing poverty alleviation tasks. Previous studies have emphasized the important role of empowering people in democracies for poverty reduction. This study shows that empowering key governmental actors in authoritarian regimes can help them increase their bargaining power and improve the performance of poverty alleviation. In addition, this paper echoes the research on political institutions of authoritarian systems and deepens the understanding of the importance of the higher-ranking institution of Chinese officials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Park et al. (2002) gave a detailed discussion on the adjustment process for the first list of NDPCs.

The meaning of "8–7 " was that China tried to basically solve the poverty problem of food and clothing for the 80 million poor people in rural areas in about seven years (from 1994 to 2000).

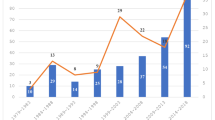

On June 13, 2001, the State Council issued the "Outline of China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development (2001–2010)", which made a second adjustment and rebalanced the indicators for NDPCs. The NDPC designation for 33 poor counties in the east had all been removed and assigned to 33 counties in the central and western regions; thus, the east no longer had any NDPCs. At the same time, as a special area, all the counties in Tibet had been targeted as NDPCs. After this, there were a total of 592 NDPCs across the country. In 2011, the Central Committee of the CCP and the State Council issued the "Outline for Poverty Alleviation and Development in China's Rural Areas (2011–2020)", which made the third adjustment to the list of NDPCs. A total of 38 were transferred from the original nationally designated poor counties and 38 were transferred from the original non-nationally designated poor counties. The total number of NDPCs nationwide remains unchanged.

Data source: the list of nationally designated poor counties published by Poverty Alleviation Development Office. Website: http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2014/12/23/art_343_981.html (access date is October 1, 2020).

Data source: record of nationally designated poor counties out of poverty during 2016–2020: http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2020/10/16/art_343_1140.html (access date is October 18, 2020).

Database of Chinese Party and Government Leading Cadres: http://cpc.people.com.cn/gbzl/index.html

The potential for a multicollinearity problem is low. We test all of the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of the main independent variables in the logit model and determine that all of the VIFs are between 1.02 and 2.10.

There were a few leaders who were promoted without leaving his position during the campaign; the proportion of these promoted county leaders in the remaining NDPCs is 4.33%, 12.06%, 4.86%, 7.32% and 5.77% respectively in the five years.

References

Ang, Y.Y. 2016. How China escaped the poverty trap. Cornell University Press.

Bachrach, P., and M.S. Baratz. 1970. Power and poverty: Theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

Beck, Nathaniel, Jonathan N. Katz, and Richard Tucker. 1998. Taking time seriously: Time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science 42: 1260–1288.

Box-Steffensmeier, J.M., and B.S. Jones. 1997. Time is of the essence: Event history models in political science. American Journal of Political Science 41: 1414–1461.

Bulman, D.J., and K.A. Jaros. 2019. Leninism and Local Interests: How Cities in China Benefit from Concurrent Leadership Appointments. Studies in Comparative International Development 54 (2): 233–273.

Di, J. 2010. Governing through campaigning: The governance strategy of the township grassroots: A case study of wheat town’s central task of afforestation in central china[in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Sociology 30 (03): 83–106.

Diaz-Cayeros, A., F. Estévez, and B. Magaloni. 2016. The political logic of poverty relief: Electoral strategies and social policy in Mexico. Cambridge University Press.

Fan, S. and C. Chan-Kang 2005. Road development, economic growth, and poverty reduction in China. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Gao, H., and A. Tyson. 2020. Poverty Relief in China: A Comparative Analysis of Kinship Contracts in Four Provinces. Journal of Contemporary China 29 (126): 901–915.

Golden, M., and B. Min. 2013. Distributive politics around the world. Annual Review of Political Science 16: 73–99.

Grindle, M.S. 2004. Good enough governance: Poverty reduction and reform in developing countries. Governance 17 (4): 525–548.

Gu, Y., X. Qin, Z. Wang, C. Zhang and S. Guo 2020. Global Justice Index Report. Chinese Political Science Review, 5(1).

Gu, Y., X. Qin, Z. Wang, C. Zhang, and S. Guo. 2021. Global Justice Index Report 2020. Chinese Political Science Review 5: 1–165.

Huang, Q., S. Rozelle, B. Lohmar, J. Huang, and J. Wang. 2006. Irrigation, agricultural performance and poverty reduction in China. Food Policy 31 (1): 30–52.

Huang, Y. 1999. Inflation and investment controls in China: The political economy of central-local relations during the reform era. Cambridge University Press.

Huang, Y. 2002. Managing Chinese bureaucrats: An institutional economics perspective. Political Studies 50 (1): 61–79.

Huang, Y., and Y. Sheng. 2009. Political decentralization and inflation: sub-national evidence from China. British Journal of Political Science 39: 389–412.

Jia, R., H. Nie, and W. Xiao. 2019. Power and publications in Chinese academia. Journal of Comparative Economics 47 (4): 792–805.

Jiang, T., K. Sun, and H. Nie. 2018. Administrative Rank, Total Factor Productivity and Resource Misallocation in Chinese Cities[in Chinese]. Management World 34 (03): 38-50+77+183.

Kang, X. 1995. Poverty and Anti-poverty Theory in China[in Chinese]. Nanning: Guangxi People’s Publishing House.

Kou, C.-W., and W.-H. Tsai. 2014. “Sprinting with small steps” towards promotion: Solutions for the age dilemma in the CCP cadre appointment system. The China Journal 71: 153–171.

Li, M. and Y. Li 2019. Innovation and Diffusion of Shantytown Renovation Policy-- A Study Based on Event History Analysis of Provincial Governments in China[in Chinese]. (09): 164–176.

Li, X., L. Yu, and L. Tang. 2019. The Process and Mechanism of China’s Poverty Reduction in the Past Seventy Years[in Chinese]. Chinese Rural Economy 10: 2–18.

Liu, Q. 2019. Equal Rights Versus Equal Needs: Global Justice or Global Virtues? Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 2: 275–291.

Ma, X. 2017. Guardians and Gridlocks: Bureaucracy, Bargaining, and Authoritarian Policymaking. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Washington.

Ma, X. 2019. Consent to Contend: The Power of the Masses in China’s Local Elite Bargain. China Review 19 (1): 1–30.

Montalvo, J. G. and M. Ravallion 2009. The pattern of growth and poverty reduction in China. The World Bank.

Ouyang, J. 2019. Political Integration and Its Operative Basis:From the Perspective of County Governance[in Chinese]. (2): 184–198+10–11.

Park, A., S. Wang, and G. Wu. 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1): 123–153.

Piazza, A., J. Li, G. Su, T. Mckinley, E. Cheng, C. Saint-Pierre, T. Sicular, B. Trangmar and R. Weller 2001. China: Overcoming rural poverty. The World Bank.

Ravallion, M. 2011. A comparative perspective on poverty reduction in Brazil, China, and India. The World Bank Research Observer 26 (1): 71–104.

Sheng, Y. 2009. Authoritarian co-optation, the territorial dimension: Provincial political representation in post-Mao China. Studies in Comparative International Development 44 (1): 71–93.

Shih, V., C. Adolph and M. Liu 2017. Getting ahead in the communist party: explaining the advancement of central committee members in China. Critical Readings on the Communist Party of China (4 Vols. Set). Brill.

Si, Y. 2020. Implementing targeted poverty alleviation: A policy implementation typology. Journal of Chinese Governance 5 (4): 439–454.

Song, Y. 2012. Poverty reduction in China: The contribution of popularizing primary education. China & World Economy 20 (1): 105–122.

Wang, J. 2007. The Politics of Poverty Mis-targeting in China. Journal of Chinese Political Science 12 (3): 219–236.

Wang, Z., and Y.W. Su. 2021. Deliberative representation: How Chinese authorities enhance political representation by public deliberation. Journal of Chinese Governance 123: 1–33.

Xi, T., Y. Yao, and M. Zhang. 2018. Capability and opportunism: Evidence from city officials in China. Journal of Comparative Economics 46 (4): 1046–1061.

Yan, J. 2020. Anti-Poverty and State Governance: The Innovation Significance of China’s Poverty-Alleviation[in Chinese]. Management World 36 (04): 209–220.

Zhang, L., J. Huang, and S. Rozelle. 2003. China’s War on Poverty: Assessing Targeting and the Growth Impacts of Poverty Programs. Journal of Chinese Economic & Business Studies 1 (3): 301–317.

Zhang, Y., X. Zhou, and W. Lei. 2017. Social capital and its contingent value in poverty reduction: Evidence from Western China. World Development 93: 350–361.

Zhang, Y. 2019. Essays on Intergovernmental Lobbying in America. Doctor of Philosophy, Texas A&M University.

Zhou, B. and H. Gao. Summary of Poverty Research and Practice (dui pinkun de yanjiu he fan pinkun shilue de zongjie. In: China Foundation for Poverty ALLEVIATION, ed. Omnibus of Best Poverty Papers, 2001 Beijing. Beijing: China Economic Publishing House, 492–535.

Zhou, F., and M. Tan. 2020. Governance Mechanism of Clear Responsibility and Its Effect[in Chinese]. Academia Bimestrie 3 (3): 49–58.

Zhou, L.-A. 2007. Governing China’s Local Officials: An Analysis of Promotion Tournament Model[in Chinese]. Economic Research Journal 42: 32–50.

Zhou, X., and L. Hou. 2003. The Children of the Cultural Revolution: Contemporary China and the Life Course[in Chinese]. In Chinese Sociology, ed. CASS Institute of Sociology RESEARCH. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

Zhu, X. and Y. Zhang 2015. Innovation and diffusion: the rise of the new administrative examination and approval system in Chinese cities[in Chinese]. Management World, (10): 91–105+116.

Acknowledgements

We have benefited from comments provided by Changdong Zhang, Xiao Ma, Ningchuan Zhang, Rundong Ji, and Hao Xi. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Wu, Z. Power and Poverty in China: Why Some Counties Perform Better in Poverty Alleviation?. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 27, 319–340 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09765-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09765-0