Abstract

Does poverty relief breed corruption? This question has been examined in several electoral polities, but not in other political settings. This study engages in this academic discussion by proposing a unique corruption mechanism in the case of China. The dual causes of National Poor Counties’ unique exit mechanism and long distance from economic hubs create a unique local poli-economic environment, in which local bureaucrats share the incentive to stay in the program, which in turn leads to an intra-elite alliance and more corruption. I test the empirical implication of these mechanisms by first building up a new county-level corruption dataset for 881 low-income counties,and then leveraging propensity score weighting to evaluate the impact of the third wave (2001–2010) of China’s poverty alleviation program on county level corruption. The results of this test show some evidence that counties participated in the third wave of the program are associated with approximately 4.4–19.7 percent increase in corruption incidence and 10.5–23.5 percent increase in numbers of convicted persons compared to similar non-participant counties. These findings highlight the importance of proper institutional designs in poverty alleviation regimes to lower the corruption incentive of local bureaucrats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Park, A., S. Wang, and G.Wu. 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1), 123-153. Zhang, L., J. Huang, and S. Rozelle. 2003 China’s War on Poverty: Assessing Targeting and the Growth Impacts of Poverty Programs. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 1 (3): 301-317. Meng, L. 2013. Evaluating China’s poverty alleviation program: A regression discontinuity approach, Journal of Public Economics 101(5): 1-11.

Zhang, Z. 2020. Consolidate the poverty alleviation achievements, study the relative poverty governance question (in Chinese). In People’s Daily. http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_56_186012.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2021. Xi, J. 2021. Taking stock of the historical achievements of povety alleviation efforts. In Hubei Daily (in Chinese). http://news.cnhubei.com/content/2021-02/25/content_13643832.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development. 2015. Prohibit the showcase project by poverty counties (in Chinese). In Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-01/30/c_127440912.htm. Accessed 2 Jan 2021.

Diaz-Cayeros, A., F. Estévez, and B. Magaloni. 2016. The Political Logic of Poverty Relief: Electoral Strategies and Social Policy in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crost, B., J. Felter and P. Johnston. 2014. Aid under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict. American Economic Review, 104(6):1833-56.

Nunn, N., and N. Qian. 2014. US food aid and civil conflict. American Economic Review 104 (6):1630-66.

The case-disclosure website of the People’s Procuratorate of China. https://www.12309.gov.cn/12309/ajxxgk/index.shtml. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

We have also tries to leverage Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD) to address the selection bias. But, probably due to inaccessibility to the data of one key variable, the RDD results are not statistically significant. So, we put the RDD discussion in the appendix. Thistlethwaite, D.L., and D.T. Campbell. 1960. Regression-discontinuity analysis: An alternative to the ex post facto experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51 (6), 309–317. Guo, S., and M.W. Fraser. 2015. Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Shaanxi provincial government. 2020. Shaanxi provincial government’s official announcement of their crack down effort on poverty relief related corruption (in Chinese). In Sohu News. https://www.sohu.com/a/428475949_99956791. Accessed Jan 8 2021.

Saleem, H., J. Wen and M.B. Khan. 2020. Determinants of corruption in China: a policy perspective, Journal of Chinese Governance, 5(3): 297-321. Gu, Y., X. Qin, Z. Wang, C. Zhang and S. Guo. 2020. Global Justice Index Report. Chinese Political Science Review. 5: (253–331).

World Bank. 1997. Helping countries combat corruption: The role of the World Bank. The World Bank: WashingtonDC.

Treisman, D. 2007. What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science 10(1): 211–44

Zhu B. 2017. MNCs, Rents and Corruption: Evidence from China. American Journal of Political Science. 61(7): 84-99.

Zhan, J. 2017. Do natural resources breed corruption? Evidence from China. Environmental and Resource Economics 66: 237–259.

Gong, T., S. Wang and H. Li. 2019. Sentencing Disparities in Corruption Cases: Evidence from China, Journal of Contemporary China 28 (116): 245-259.

https://www.12309.gov.cn/12309/ajxxgk/index.shtml. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Park, A., S. Wang, and G. Wu. 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1), 123-153. Meng, L. 2013. Evaluating China’s poverty alleviation program: A regression discontinuity approach, Journal of Public Economics 101(5): 1-11. Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212. Li, M., and Z. Wu. 2021. Power and Poverty in China: Why Some Counties Perform Better in Poverty Alleviation?. Journal of Chinese Political Science.

Park, A., Wang, S., Wu, G., 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1), 123-153.

Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212.

Yadav, V., and B Mukherjee. 2016. The Politics of Corruption in Dictatorships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

But this paper doesn’t give and test the causal mechanism. See de Kadt, D., and E.S. Lieberman. 2015. Do citizens reward good service? voter responses to basic service provision in Southern Africa. MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2015-25. Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2668334. Accessed 10 Jan 2021.

Brollo, Fernanda, Tommaso Nannicini, Roberto Perotti, and Guido Tabellini. 2013. The Political Resource Curse. American Economic Review, 103 (5):1759-96.

Diaz-Cayeros, A., F. Estévez, and B. Magaloni. 2016. The Political Logic of Poverty Relief: Electoral Strategies and Social Policy in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yadav, V., and B Mukherjee. 2016. The Politics of Corruption in Dictatorships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klasnja M., A.T. Little and J.A. Tucker. 2018. Political Corruption Traps. Political Science Research and Methods 6(3): 413-428.

Evans D. K., B. Holtemeyer and K. Kosec. 2019. Cash Transfers Increases Trust in Local Government. World Development. 114: 138-155

Zuo, C., Z. Wang, and Q. Zeng. 2021. From poverty to trust: political implications of the anti-poverty campaign in china. International Political Science Review. 1-22. Online first.

For more information, see Park, A., Wang, S., Wu, G., 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1), 123-153.

Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212. The “2700 Yuan” standard of rural net income per capita in RMF is proposed by Qin and Chong’s paper on page 199. However, I think they made a typo. The “2700 yuan” actually is the threshhold for GDP per capita. I have read dozens of academic articles in Chinese and English and search the government website, but in vain I find none of them have ever mentioned the standard for the rural net income per capita for RMF counties. But, when I do Chinese language online search, I find a few web source arguing that 1500 is the standard for the rural net income per capita for RMF counties. Please check the following websites for this argument.

https://www.docin.com/p-1581179561.html. https://www.doc88.com/p-9157319609924.html?r=1. Accessed 20 Oct 2021.

State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development (in Chinese). 2012. http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2012/3/19/art_50_23706.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021. Xinhua Net. 2012. 38 Counties were removed from the National Poverty Counties Program (in Chinese). https://china.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJuDW4. Accessed 1 Sep 2021.

Xi, J. 2021. Taking stock of the historical achievements of povety alleviation efforts. In Hubei Daily (in Chinese). http://news.cnhubei.com/content/2021-02/25/content_13643832.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

China Youth Net. 2011. Online source exposes the White House style luxury buildings in Wangjiang County of Anhui Province (in Chinese). In China Youth Net. http://news.youth.cn/tptt/201103/t20110326_1527497.htm. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

People’s Daily. 2014. Report on luxury buildings in Fang county in Hubei province (in Chinese). http://finance.people.com.cn/BIG5/n/2014/0408/c1004-24841373.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Zhang, L. 2014. Government of Ningcheng County reply: Luxury Buildings have been rectified (in Chinese). In People’s Daily. http://house.people.com.cn/n/2014/0410/c164220-24866451.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Qin, C. and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212.

China Youth Net. 2014. Taking stock of 26 luxury administrative buildings (in Chinese). http://news.youth.cn/gn/201412/t20141201_6143047.htm. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Rubin, D. 1974. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and non-randomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology 66 (688): 701. Imbens, G.W. 2015. Matching methods in practice: Three examples, Journal of Human Resources, 50(2): 373-419.

Rubin, D.B. 1973. Matching to remove bias in observational studies. Biometrics 29(159):83. Rosenbaum, P.R., and D.B. Rubin. 1983. The central role of the Propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41-55.

Guo, S., and M.W. Fraser. 2015. Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Gary, K., and R. Nielsen. 2019. Why propensity scores should not be used for matching, Political Analysis, 27(4): 435-454.

Olmos, A., and P. Govindasamy. 2015. A Practical Guide for Using Propensity Score Weighting in R. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 20(13):1-8. Available online: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=20&n=13. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

McCaffrey, D.F., G. Ridgeway, and A.R. Morral. 2004. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating causal effects in observational studies. Psychological Methods 9 (4): 403-425. Ridgeway, G. (2015). gbm: Generalized Boosted Regression Models. R package version 2.1.1

https://www.12309.gov.cn/12309/ajxxgk/index.shtml. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Kautz, C. 2020. Power Struggle or Strengthening the Party: Perspectives on Xi Jinping’s Anticorruption Campaign. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25(3): 501–511. Tian, Y. 2021. The Anti-corruption Discourse of China: Cracking down on “Tigers”. Fudan Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 14: (587–610).

We also used the number of convicted cadres at village level, section leadership level, and division director level separately as the outcome variable. In these models, the coefficients of NPC designation were all insignificant. These models are shown in the Table 9 of the appendix, and yielded similar results.

As mentioned earlier, these 2 variables in together constitute 10% weight to the “631” index. So, exclusion of these two variables would not deviate our weighting approach too much from the real world process. Moreover, we still add these 2 variables in the outcome models as confounders.

Li, H., and T. Gong. 2020. Panacea or Pandora’s Box? The Dual Effect of Marketization on Corruption. Problems of Post-Communism 67 (2): 1-15.

Zhu, B.L. 2017. MNCs, Rents and Corruption: Evidence from China. American Journal of Political Science. 61(7): 84-99.

Zhan, J.V. 2017. Do Natural Resources Breed Corruption? Evidence from China. Environmental and Resource Economics 66: 237–259.

Thistlethwaite, D.L., and D.T. Campbell. 1960. Regression-discontinuity analysis: An alternative to the ex post facto experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51 (6), 309–317. Ludwig, J. and L.M. Douglas. 2007. Does Head Start Improve Children’s Life Chances? Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (1): 159-208

Park, A., Wang, S., Wu, G., 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1), 123-153. Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212.

Joshua, D.A, and V. Lavy, Using Maimonides’ rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (2): 533–575.

Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192-212.

Cattaneo, M.D., M. Jansson and X.W. Ma. 2018. Manipulation Testing based on Density Discontinuity. Stata Journal 18(1): 234-261.

Calonico, S., M.D. Cattaneo and R. Titiunik. 2015. rdrobust: An R Package for Robust Nonparametric Inference in Regression-Discontinuity Designs The R Journal 7 (1): 38-51.

References

Brollo, Fernanda, Tommaso Nannicini, Roberto Perotti, and Guido Tabellini. 2013. The Political Resource Curse.". American Economic Review 103 (5): 1759–1796.

Calonico, S., M.D. Cattaneo, and R. Titiunik. 2015. rdrobust: An R Package for Robust Nonparametric Inference in Regression-Discontinuity Designs. The R Journal 7 (1): 38–51.

Cattaneo, M.D., M. Jansson, and X.W. Ma. 2018. Manipulation Testing based on Density Discontinuity. Stata Journal 18 (1): 234–261.

China Youth Net. 2011. Online source exposes the White House style luxury buildings in Wangjiang County of Anhui Province (in Chinese). In China Youth Net. http://news.youth.cn/tptt/201103/t20110326_1527497.htm. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

China Youth Net. 2014. Taking stock of 26 luxury administrative buildings (in Chinese). in China Youth Net. http://news.youth.cn/gn/201412/t20141201_6143047.htm. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Crost, B., J. Felter, and P. Johnston. 2014. Aid under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict. American Economic Review 104 (6): 1833–1856.

de Kadt, D., and E.S. Lieberman. 2015. Do citizens reward good service? voter responses to basic service provision in Southern Africa. MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2015-25. Available at SSRN: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2668334. Accessed 10 Jan 2021.

Diaz-Cayeros, A., F. Estévez, and B. Magaloni. 2016. The Political Logic of Poverty Relief: Electoral Strategies and Social Policy in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, D.K., B. Holtemeyer, and K. Kosec. 2019. Cash Transfers Increases Trust in Local Government. World Development 114: 138–155.

Gary, K., and R. Nielsen. 2019. Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis 27 (4): 435–454.

Gong, T., S. Wang, and H. Li. 2019. Sentencing Disparities in Corruption Cases: Evidence from China. Journal of Contemporary China 28 (116): 245–259.

Gu, Y., X. Qin, Z. Wang, C. Zhang, and S. Guo. 2020. Global Justice Index Report. Chinese Political Science Review 5: 253–331.

Guo, S., and M.W. Fraser. 2015. Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Imbens, G.W. 2015. Matching methods in practice: Three examples. Journal of Human Resources 50 (2): 373–419.

Kautz, C. 2020. Power Struggle or Strengthening the Party: Perspectives on Xi Jinping’s Anticorruption Campaign. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25 (3): 501–511.

Klasnja, M., A.T. Little, and J.A. Tucker. 2018. Political Corruption Traps. Political Science Research and Methods 6 (3): 413–428.

Li, H., and T. Gong. 2020. Panacea or Pandora’s Box? The Dual Effect of Marketization on Corruption. Problems of Post-Communism 67 (2): 1–15.

Li, M., and Z. Wu. 2021. Power and Poverty in China: Why Some Counties Perform Better in Poverty Alleviation?. Journal of Chinese Political Science.

Joshua, D.A., and V. Lavy, Using Maimonides’ rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (2): 533–575

Ludwig, J., and L.M. Douglas. 2007. Does Head Start Improve Children’s Life Chances? Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (1): 159–208.

McCaffrey, D.F., G. Ridgeway, and A.R. Morral. 2004. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating causal effects in observational studies. Psychological Methods 9 (4): 403–425.

Meng, L. 2013. Evaluating China’s poverty alleviation program: A regression discontinuity approach. Journal of Public Economics 101 (5): 1–11.

Nunn, N., and N. Qian. 2014. US food aid and civil conflict. American Economic Review 104 (6): 1630–1666.

Olmos, A., and P. Govindasamy. 2015. A Practical Guide for Using Propensity Score Weighting in R. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 20(13):1-8. Available online: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=20&n=13. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Park, A., S. Wang, and G. Wu. 2002. Regional poverty targeting in China. Journal of Public Economics 86 (1): 123–153.

People’s Daily. 2014. Report on luxury buildings in Fang county in Hubei province (in Chinese).

http://finance.people.com.cn/BIG5/n/2014/0408/c1004-24841373.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Qin, C., and T.T.L. Chong. 2018. Can poverty be alleviated in China? Review of Income and Wealth. 64 (1): 192–212.

Ridgeway, G. 2015. gbm: Generalized Boosted Regression Models. R package version 2 (1): 1.

Robinson, J.A., R. Torvik, and T. Verdier. 2006. Political Foundations of the Resource Curse. Journal of Development Economics 79: 447–468.

Rosenbaum, P.R., and D.B. Rubin. 1983. The central role of the Propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70 (1): 41–55.

Ross, M.L. 1999. The Political Economy of the Resource Curse. World Politics 51 (2): 297–322.

Rubin, D.B. 1973. Matching to remove bias in observational studies. Biometrics 29 (159): 83.

Saleem, H., J. Wen, and M.B. Khan. 2020. Determinants of corruption in China: a policy perspective. Journal of Chinese Governance 5 (3): 297–321.

Shaanxi provincial government. 2020. Shaanxi provincial government’s official announcement of their crack down effort on poverty relief related corruption (in Chinese). In Sohu News. https://www.sohu.com/a/428475949_99956791. Accessed Jan 8 2021.

State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development. 2012. http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2012/3/19/art_50_23706.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development. 2015. Prohibit the showcase project by poverty counties (in Chinese). In Xinhua Net. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-01/30/c_127440912.htm. Accessed 2 Jan 2021.

The case-disclosure website of the People’s Procuratorate of China. https://www.12309.gov.cn/12309/ajxxgk/index.shtml. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Thistlethwaite, D.L., and D.T. Campbell. 1960. Regression-discontinuity analysis: An alternative to the ex post facto experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology 51 (6): 309–317.

Tian, Y. 2021. The Anti-corruption Discourse of China: Cracking down on “Tigers.” Fudan Journal of Humanities and Social Science 14: 587–610.

Treisman, D. 2007. What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 211–244.

Rubin, D. 1974. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and non-randomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology 66 (688): 701.

World Bank. 1997. Helping countries combat corruption: The role of the World Bank. The World Bank: WashingtonDC.

Xi, J. 2021. Taking stock of the historical achievements of povety alleviation efforts. In Hubei Daily (in Chinese). http://news.cnhubei.com/content/2021-02/25/content_13643832.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Zhang, L., J. Huang, and S. Rozelle. 2003. China’s War on Poverty: Assessing Targeting and the Growth Impacts of Poverty Programs. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 1 (3): 301–317.

Zhang, L. 2014. Government of Ningcheng County reply: Luxury Buildings have been rectified (in Chinese). In People’s Daily. http://house.people.com.cn/n/2014/0410/c164220-24866451.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

Zhang, Z. 2020. Consolidate the poverty alleviation achievements, study the relative poverty governance question (in Chinese). In People’s Daily. http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_56_186012.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Zhan, J. 2017. Do natural resources breed corruption? Evidence from China. Environmental and Resource Economics 66: 237–259.

Zhu, B. 2017. MNCs, Rents and Corruption: Evidence from China. American Journal of Political Science. 61 (7): 84–99.

Zuo, C., Z. Wang, and Q. Zeng. 2021. From poverty to trust: political implications of the anti-poverty campaign in china. International Political Science Review. 1-22. Online first.

Acknowledgements

I thank Cong Qin and Terence Tai Leung Chong for providing their data. I thank Shiping Tang, Bruce Dickson, Michael K. Miller, Stephen Haggard, Hui Li, Shuo Chen, Chao-yo Cheng, Fengming Lu, Evangjelia Sali and Miriam Gochnauer for helpful comments on drafts of the paper. This paper has been presented at Fudan-UCSD Young Scholar Meeting (UCSD, May 2016), Sigur Center for Asian Studies Visiting Scholar Talk Serious (George Washington University, December 2016), Fudan Comparative Politics Seminar (Fudan Univeristy, March, 2017). This research is supported by the Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (2019EGJ002), Innovative Research Team of Shanghai International Studies University and two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest Statement

I declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled, “Does Poverty Relief Breed Corruption? An Evaluation of China’s Poverty Alleviation Program”.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Regression results using number of convicted cadres at village level, section leadership level, and division director level separately as the outcome variable

Table 7

Fuzzy RDD Estimation

At the very start of this research process, we thought RDD is a suitable identification strategy to estimate the causal effect of NPC designation on corruption, because according to the national policy, counties could enter China’s poverty alleviation programs if they were below certain poverty lines. In other words, the assignment rule for NPCs creates a discrete relationship between a county’s pre-program economic performance (the running variable) and its probability of being allowed to participate in the program (the treatment status). Under this condition, RDD is quite applicable to avoid selection bias of in the assignment of NPC status and estimate its effect.Footnote 50 To make things more complicated, due to various technique and political reasons,Footnote 51 in the real NPCs designation process, the selection criteria are not perfectly followed. Because no deterministic relationship exists between the treatment status and the running variable, we have to use fuzzy RDD to estimate the complier average causal effect of the program (2001-2010) on the outcome variable, i.e., county-level corruption in (2014-2016), and conceptualize the RD approach in an instrumental variable (IV) framework.Footnote 52

The “631” index of the third wave comprises of four economic indicators in 2001: the poverty incidence in the county (weighted at 60%), the rural net income per capita (weighted at 30% with different threshold for different counties), and GDP per capita and local government revenue per capita (weighted at 10%). Because the data on county-level poverty incidence in 2000 has not been made public and there is no threshold attached to this variable, this paper only used data on the other three indicators with clear thresholds in 2000 to construct the running variable. Exploiting these three indicators’ respective weights, we computed the running variable—poverty index to approach the original “631” index for each county:

Moreover, to select eligible poor counties into the third wave, the basic poverty line was set at 1300 Yuan for rural net income per capita, 2700 Yuan for GDP per capita, and 120 Yuan for government revenue per capita for ordinary counties, while the standard rose to 1500 Yuan for rural net income per capita for RMF counties. Based on these thresholds, we computed two cutoff points respectively for ordinary counties and RMF counties.

The data of the three poverty line indicators and RMF status were collected and kindly shared by Cong Qin and Terence Tai Leung Chong from the following sources: the rural net income data are from China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database supported by China Statistics Press; GDP and local government revenue per capita are from University of Michigan’s China Data Online database; lists of old revolutionary areas, minority autonomous areas and frontier counties were obtained from An Outline of Chinese Rural Economic Statistics by County 1988 and the CNKI database.Footnote 53

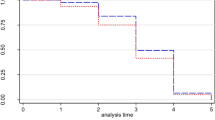

We used fuzzy RDD to estimate the complier average causal effect of the program (2001-2010) on the county level corruption. Moreover, because the cutoff point for ordinary counties and RMF counties are different, we estimated the effects in two subsamples. But before estimation, we needed to validate the fuzzy RDD design. Figure 5 and 6 show that, in both of the two subsamples, counties below the respective cutoffs are more likely to participate in the NPC program, while counties above the respective cutoffs are more likely to be excluded from the NPC program. But, the selection criteria are not perfected followed, so the fuzzy RDD is a legitimate method in such conditions.

Then we moved on to assess if there is systematic manipulation on the running variable. A manipulation test in this context amounts to testing whether there is a disproportional number of counties are situated above the cutoff point relative to those present below the cutoff. Figure 7 and 8 show that there is some manipulation in RMF counties, but not in ordinary counties. We used a formal RD Manipulation Test (Table 7) to quantify the extent of manipulation and found that: there is no statistical evidence (p = 0.9411) that there is systemic manipulation in ordinary counties; but there is weak statistical evidence (p = 0.095) that there is systemic manipulation in RMF counties.Footnote 54

In RDD, visualization of the estimate is its defining feature. But to conserve space, we only present two RD plots (Fig. 9 and 10) . Both of the plots put the number of filed corruption cases on the y-axis and the poverty index on the x-axis, and they show: in ordinary counties, counties just below the cutoff have a higher number of corruption cases than counties just above it; but in RMF counties, no such difference can be discerned. As our next step, we employed nonparametric methods of fuzzy RDD to estimate the causal effect of the NPC program for compliers.Footnote 55

The results are presented in the Table 8. For the purpose of robustness, we showed the estimates using all the 5 corruption indicators respectively for both ordinary and RMF counties. The estimation of bandwidths and effective numbers of observations was conducted using a local-linear estimator with a local-quadratic bias-correction estimate, with a triangular kernel. For ordinary counties, the RD point estimators with each of the five corruption indicators used as outcome variables were always positive but not statistically significant. The same is true for most of the models for the RMF counties. Only the last two models for RMF counties show negative and insignificant effects. These results suggest that, around the cutoff in our artificial RDD, compliers in treatment group (NPC program participants) might increase corruption compared to compliers in control group (non-participants), but this effect is still questionable and unstable in a statistical sense.

We think these insignificant results arise from the fact that the composite “631” index makes it difficult to evaluate it with RDD, because the index didn’t set a clear cutoff point for the poverty incidence variable which weighs at 60 percent in the index. So, while we tried to approach this index with the other three constituent variables, we are still one step away from the real program assignment process. As a result, the fuzzy RDD only utilized a few complier observations and excluded those non-complier observations based on our arbitrarily constructed running variable and cutoff points. In other words, the fuzzy RDD dropped a few useful observations. Thus, we turned to the propensity score weighting method as the main identification strategy to tackle this problem (Table 9).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K. Does Poverty Relief Breed Corruption? An Evaluation of China’s Poverty Alleviation Program. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 27, 341–374 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09785-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09785-w