Abstract

Factionalism and performance are the dominant explanations of elite dynamics in China. While recent studies focus on the interaction between the two, this article introduces a crucial mediating factor—fiscal transfers—which has largely been overlooked. At the provincial level, leaders have incentives to obtain more transfers from the center and invest to boost GDP growth. Simultaneously decreasing their reliance on transfers is another performance indicator. The resulting balance is political, as leaders may receive more support based on their political connections. Based on two datasets of leaders and provincial finances from 1997 to 2015 and the introduction of instrumental variables, this article finds that while political ties can increase fiscal transfers, they also provide crucial information for leaders to achieve the optimal balance between transfers and growth. The political nature of transfers is also much more pronounced for provincial secretaries than governors. This study has implications for the literature on elite politics and links this research field with the literature on fiscal decentralization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although such decisions must be approved by the provincial people’s congress, this is basically a rubber-stamping process [11].

For example, the average tenure of governors dropped from over 3 years in 1990 to under 2.5 years in the early 2000s [19 , p. 90].

A higher growth rate would allow provinces to spend and transfer more in the future, but the tradeoff still exists once the size of the economy is accounted for.

The Prais-Winsten AR(1) model returns similar results (see the Appendix).

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, the “Shanghai clique” is called as such but not “Shanghai-and-surrounding-provinces clique.” It is less likely that cliques would be formed external to provinces, as they are sizable units. To clarify, I am not necessarily suggesting that a patron would always place clients in neighboring provinces to expand his base. The instrument would be valid as long as there is a correlation between political ties and geographical proximity of provinces, which can be attributed to regional cliques, the similar characteristics of neighboring provinces, and the nature of political appointment (discussed below). I thank the reviewer for raising this point.

For example, the instrument for the secretary ties of Shanxi in 1998 is the average secretary ties/promotion outcomes of Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Henan, and Shaanxi in 1997.

For example, Choi [6] classified Jiang Zemin’s faction as those who had connections with him when he served in the First Ministry of Machine Building Industry and the “Shanghai clique,” i.e., those who advanced their careers in Shanghai under Jiang. Yet, those who had relationships with Zhu Rongji were excluded.

Shih et al. [35] defined work ties as the connection between an official and a leader working in the same work unit within two administrative steps for over a year.

While some scholars have focused on revenue-collection ability, fiscal transfer also takes into account the size of the public sector (such as spending) and captures the extent to which the province depends on/contributes to the central government, which should be the most relevant consideration for central leaders.

Other variables, such as whether the official is female or an ethnic minority are also tested but are insignificant across all models. They are excluded for model parsimony.

The raw figures of population and GDP per capita are used in the main models. Using their log-transformations does not affect the main results, as reported in the Appendix.

Detailed correlation figures for this set of variables are reported in the Appendix.

Although GDP is a key predictor of transfer gap, the effect of secretary ties is significant in both sub-samples of high/low GDP provinces (results are presented in the Appendix).

In addition, following Sovey and Green [38], the t-ratio of the first stage must be around 3 for a single instrumental variable. This is also fulfilled in the current analysis.

In other words, as province fixed effects eliminate all variations across units and focus only on within-unit variations, we are comparing the effect between those who were promoted and not promoted in the same province, thus minimizing potential endogeneity.

This does not mean that the level of transfers is irrelevant to promotion. First, the difference is merely less pronounced among those with strong ties. Second, the predictions account for the average level of transfers of the province.

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for this insightful comment.

References

Ang, Yuen Yuen. 2016. Co-optation and clientelism: Nested distributive politics in China’s single-party dictatorship. Studies in Comparative International Development 51 (3): 235–256.

Angrist, Joshua D., and Jorn-Steffen Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bo, Zhiyue. 2002. Chinese Provincial Leaders: Economic Performance and Political Mobility since 1949. Armonk: East Gate Book.

Burns, John P., ed. 1989. The Chinese Communist Party's Nomenklatura System. Armonk: ME Sharpe.

Chen, Ting, and J.S.-S. Kung. 2016. Do land revenue windfalls create a political resource curse? Evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics 123: 86–106.

Choi, Eun Kyong. 2012. Patronage and performance: Factors in the political mobility of provincial leaders in post-Deng China. The China Quarterly 212: 965–981.

Dittmer, Lowell. 1995. Chinese informal politics. The China Journal 34: 1–34.

Guo, Gang. 2007. Retrospective economic accountability under authoritarianism: Evidence from China. Political Research Quarterly 60 (3): 378–390.

Guo, Gang. 2009. China's local political budget cycles. American Journal of Political Science 53 (3): 621–632.

Hillman, Ben. 2010. Factions and spoils: Examining political behavior within the local state in China. The China Journal 64: 1–18.

Huang, Bihong, and Kang Chen. 2012. Are intergovernmental transfers in China equalizing? China Economic Review 23 (3): 534–551.

Huang, Yasheng. 1996. Inflation and investment controls in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huang, Jing. 2006. Factionalism in Chinese communist politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Imai, Kosuke, Luke Keele, Dustin Tingley, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2011. Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review 105 (4): 765–789.

Jia, Ruixue, Masayuki Kudamatsu, and David Seim. 2015. Political selection in China: The complementary roles of connections and performance. Journal of the European Economic Association 13 (4): 631–668.

Knight, John, and Li Shi. 1999. Fiscal decentralization: Incentives, redistribution and reform in China. Oxford Development Studies 27 (1): 5–32.

Knutsen, Carl Henrik. 2011. Democracy, dictatorship and protection of property rights. Journal of Development Studies 47 (1): 164–182.

Knutsen, Carl Henrik, and Magnus Rasmussen. 2018. The autocratic welfare state: Old-age pensions, credible commitments, and regime survival. Comparative Political Studies 51 (5): 659–695.

Landry, P.F. 2008. Decentralized authoritarianism in China: The Communist party’s control of local elites in the post-Mao era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landry, Pierre F., Xiaobo Lü, and Haiyan Duan. 2018. Does performance matter? Evaluating political selection along the Chinese administrative ladder. Comparative Political Studies 51 (8): 1074–1105.

Li, Cheng. 2014. Xi Jinping’s inner circle. China Leadership Monitor 43: 30.

Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou. 2005. Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. Journal of Public Economics 89 (9): 1743–1762.

Lu, Shenghua, Yuting Yao, and Hui Wang. 2021. Testing the Relationship between Land Approval and Promotion Incentives of Provincial Top Leaders in China. Journal of Chinese Political Science: 1–27.

Lu, Xiaobo, and Pierre Landry. 2014. Show me the money: Interjurisdiction political competition and fiscal extraction in China. American Political Science Review 108 (3): 706–722.

Luo, Weijie, and Shikun Qin. 2021. China’s local political turnover in the Twenty-First Century. Journal of Chinese Political Science: 1–24.

Maskin, Eric, Yingyi Qian, and Xu. Chenggang. 2000. Incentives, information, and organizational form. The Review of Economic Studies 67 (2): 359–378.

Meyer, David, Victor C. Shih, and Jonghyuk Lee. 2016. Factions of different stripes: Gauging the recruitment logics of factions in the reform period. Journal of East Asian Studies 16 (1): 43–60.

Miller, A. L. 2008. Institutionalization and the changing dynamics of Chinese leadership politics. In China’s Changing Political Landscape: Prospects for Democracy, ed. Cheng Li. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 61-79.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook (Zhongguo Tongji Nianjian) China Statistics Press (various years).

O’Brien, Kevin, and Lianjiang Li. 1999. Selective policy implementation in rural China. Comparative Politics 31 (2): 167–186.

Ong, L.H. 2012. Fiscal federalism and soft budget constraints: The case of China. International Political Science Review 33: 455–474.

Persson, Petra, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2012. Elite capture in the absence of democracy: Evidence from backgrounds of Chinese provincial leaders. Working paper: Stanford University.

Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 2003. The economic effect of constitutions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Raiser, Martin. 1998. Subsidising inequality: Economic reforms, fiscal transfers and convergence across Chinese provinces. The Journal of Development Studies 34 (3): 1–26.

Shih, Victor, Christopher Adolph, and Mingxing Liu. 2012. Getting ahead in the communist party: Explaining the advancement of central committee members in China. American Political Science Review 106 (1): 166–187.

Shih, Victor, David Meyer, and Jonghyuk Lee. 2016. CCP Elite Database.

Shih, Victor, Wei Shan, and Mingxing Liu. 2010. The Central Committee past and present: A method of quantifying elite biographies. In Sources and methods in Chinese politics, eds. Allen Carlson, Mary E. Gallagher, Kenneth Lieberthal, and Melanie Manion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 51-68.

Sovey, Allison, and Donald Green. 2010. Instrumental variables estimation in political science: A readers’ guide. American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 188–200.

Tao, Yi-Feng. 2006. The evolution of ‘political business cycle’ in post-Mao China. Issues & Studies 42 (1): 163–194.

Tochkov, Kiril. 2007. Interregional transfers and the smoothing of provincial expenditure in China. China Economic Review 18 (1): 54–65.

Tsai, Pi-Han. 2016. Fiscal incentives and political budget cycles in China. International Tax and Public Finance 23 (6): 1030–1073.

Wan, Xin, Yuanyuan Ma, and Kezhong Zhang. 2015. Political determinants of intergovernmental transfers in a regionally decentralized authoritarian regime: Evidence from China. Applied Economics 47 (27): 2803–2820.

Wong, Christine, and Richard Bird. 2008. China’s fiscal system: A work in progress. In China’s great economic transformation, eds. Loren Brandt and Thomas Rawski. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 429-466.

Wong, Stan Hok-Wui, and Zeng Yu. 2018. Getting ahead by getting on the right track: Horizontal mobility in China’s political selection process. Journal of Contemporary China 109: 61–84.

Wong, Stan Hok-Wui, and Zeng Yu. 2020. Familiarity breeds growth: The impact of factional ties on local cadres' economic performance in China. Economics & Politics 32 (1): 143–171.

World Bank. 2007. China: Improving rural public finance for the harmonious society. Beijing: World Bank.

Wu, Alfred M., and Wen Wang. 2013. Determinants of expenditure decentralization: Evidence from China. World Development 46: 176–184.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151.

Yang, Dali L. 2004. Remaking the Chinese leviathan: Market transition and the politics of governance in China. Stanford University Press.

Yu, Qing, and Kaiyuen Tsui. 2005. Factor decomposition of sub-provincial fiscal disparities in China. China Economic Review 16 (4): 403–418.

Zhao, Dingxin. 2009. The mandate of heaven and performance legitimation in historical and contemporary China. American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 416–433.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the support of the Strategic Research Fund, Department of Social Sciences, Education University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Appendix to “Performance, Factions, and Promotion in China: The Role of Provincial Transfers”

Appendix to “Performance, Factions, and Promotion in China: The Role of Provincial Transfers”

A1. Summary of Datasets and Details of Variables Used

A2. Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables

A3. Correlation Figures for Provincial Leader Dataset

A4. Correlation Figures for Provincial Transfer Dataset

A5. Correlation Figures for Instrumental Variables

B1. Note on the Coding of Factional Ties

B2. Note on the Coding of Promotion

C1. Robustness Tests

A6. Probit Model of Provincial Leader Promotion

A7. Robustness Tests for Models on Provincial Transfer

A8. Estimations for Leaders Based on Career Outcome

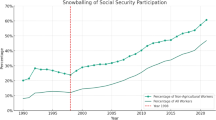

A9. Provincial GDP and Transfer Gap

C2. Instrumental Variables Regressions

A10. First Stage Instrumental Variables Regressions

D. References Used

B1. Note on the Coding of Factional Ties

The coding followed the methodology developed by Shih and colleagues (Shih 2004; 2008; Shih et al. 2010, 2012). Three types of ties, namely birth, education, and work (xitong), are developed to capture factional ties between provincial secretaries/governors and any member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo (PSC) with dummy variables (1 = existence of ties; 0 = otherwise; missing values are dropped).

Birth ties capture whether the provincial leader has the same birth place (native province) as any PSC member. Education ties measure if the leader has a shared institution of higher education as any PSC member during the same period of time. Work ties capture whether the leader had previously worked in the same "xitong" as any member of the PSC. Xitong, or bureaucratic grouping, is defined as a ministry or a province, but not a group of ministries (e.g., First Ministry of Machine Building is different from Second Ministry of Machine Building). The work tie between the two also has to be 1) within two administrative steps from each other; 2) during the same period of time, and 3) lasting for at least half a year (Shih 2004). Codings are done from scratch for 1990-2015 (although the study only uses 1997-2015) based on the new CCP Elite Database (Shih et al. 2016), which is the most updated and systematic database of all previous contributions.

The validity of my codings is verified by cross-checking with the data provided by Shih (2004). First, the measure provided by Shih (2004) aggregates the ties for both provincial secretaries and governors for a given province-year, i.e., it would assign a 1 for birth tie if either the secretary or the governor has the relevant tie. In my version the data for provincial secretaries and governors are separately coded. Second, Shih’s (2004) coding only covers up to 2004, and I extend the dataset to 2015. Noting these differences, while most of my data are the same as Shih’s (2004), there are two other minor discrepancies. First, regarding the coding of birth ties, it appears that Shih (2004) did not clearly distinguish between the actual place of birth (chusheng di 出生地) from the native place (jiguan籍貫) of some leaders (*although Shih has a separate variable, NATIVE, recording the native province of PSC members). Which this is not an issue for most leaders, some cases become ambiguous. For example, while both Li Peng and Qiao Shi were born in Shanghai, their native places were used in the coding (Sichuan and Zhejiang respectively). In my codings I have focused exclusively on native place for better consistency. Second, there are some codings in Shih’s (2004) data that are believed to be typographical errors. For example, in Tianjin’s birth tie and education tie are coded as 1 in 1995, whereas both ties are 0 in the years before and after (1994 and 1996). Tianjin’s governor and party secretary did not change during the period to warrant such a shift; there was also no change in the composition of the 14th PSC (1992-1997; excluding ordinary Politburo members). The reason for the same shift in Hebei 1995 was also unclear. These are corrected in my dataset.

B2. Note on the Coding of Promotion

In this study, promotion is coded as a dummy variable to capture upward promotion (PROMOTION = 1) as opposed to other career changes (= 0; i.e., transfer, dismissal, demotion, retirement, and death). The coding methodology mainly adopts Landry et al.’s (2017). The codes apply to the official’s post within 12 months of exiting his/her provincial office; therefore, if a promotion occurred within 12 months after a lateral transfer, the outcome would still be coded as a promotion. Promotion for provincial secretaries include a position in a higher level party/state organ such as in the Politburo Such appointments can also be concurrent to their provincial position. Governors are usually promoted to the post of provincial secretary or minister of a central bureau. CCP Elite Database (Shih et al. 2016), the China Vitae, and miscellaneous self-collected biographies.

The results of this study are not sensitive to the specific coding of PROMOTION. As discussed in the manuscript (footnote 6), the results are robust to excluding promotion to national offices (e.g., vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress and the Political Consultative Conference). Alternatively, the dropping of cases of retirement and death would also not affect the findings (i.e., only compare promotion against transfer, dismissal, and demotion).

C1. Robustness Tests

As discussed in the manuscript, BUDGET SURPLUS is the alternative measure of transfer/fiscal dependence and will be used as in robustness tests. Results are reported in Table 11 here. Although there are some variations in the level and significance of some variables, the main findings are identical to the models using TRANSFER GAP reported in the manuscript. Robustness test using BUDGET SURPLUS in the Provincial Transfer Dataset (second set of tests) is reported in Table 4 in the manuscript.

Next, robustness tests for the Provincial Transfer Dataset are shown in Table 12. Besides the inclusion of year fixed effects (in the manuscript), temporal dynamics are further assessed by including variables counting the year of the leaders’ tenure (Model M8) and dummies for each session of the CCP National Congress (M9). Model 10 includes Han people as a share of total population to control for the impact of ethnic composition. As mentioned in the manuscript, this greatly reduces the coverage of the dataset as this variable is not available after 2010. Models 12 and 13 repeat the baseline model by replacing population and GDP by their logarithmic transformation respectively. The main findings across all of these robustness test hold, in that secretary ties significantly increase TRANSFER GAP, whereas the effect of governor ties is in the same direction, but smaller in size and at times loses significance.

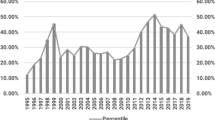

Finally, in Table 13, Models 14-17 repeat the analysis by dividing the sample based on leaders’ career outcome, i.e., whether they are promoted. Models 14 and 15 divide by secretary while 16 and 17 by governor. Predicted effects plotted in Fig. 3 in the manuscript are based the estimations returned by these four models.

Another robustness test is done by re-testing the effect of political ties in determining transfer gap. All provinces are divided into high/low GDP by mean. Here, data availability prevents a similar estimation using the PCSE model (which requires all provinces to have the same year in the model). Therefore, a simple OLS is used here. The result shows that the effect of secretary ties is significant in both high/low GDP provinces.

C2. Instrumental Variables Regressions

Next the first-stage regression results from instrumental variable regression models (2SLS fixed effects) are presented (second-stage results in Tables 5 in the manuscript). In these first-stage regressions, the independent variables are the lagged average of neighboring provincial secretaries’ ties and promotion outcomes introduced in the article alongside all other covariates in the second-stage regressions; the dependent variable is secretary/governor ties. As shown in Table 14, these two instruments have a significant relationship with secretary ties, although it is not always significant for that of the governors. F-tests of excluded instruments, suggested by Angrist and Pischke (2009), can be used to assess whether an endogenous regressor is weakly identified. Again, whereas this measure is significant for secretary ties, it is not consistent for governors. In sum, the instruments should be considered strong and valid for the effect of secretary’s political ties, and slightly less for governors (Table 15).

D. References Used

Angrist, Joshua D. and Jorn-Steffen Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shih, Victor. 2004 Database on Provincial Factional Affiliation with Standing Committee Members of the Chinese Communist Party: 1978-2004.

Shih, Victor. 2008. Factions and Finance in China: Elite Conflict and Inflation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shih, Victor, Christopher Adolph, and Mingxing Liu. "Getting ahead in the communist party: explaining the advancement of central committee members in China." American Political Science Review 106.1 (2012): 166-187.

Shih, Victor, Wei Shan, and Mingxing Liu. "The Central Committee past and present: a method of quantifying elite biographies." Sources and Methods in Chinese Politics, edited by Allen Carlson, Mary E. Gallagher, Kenneth Lieberthal, and Melanie Manion (2010): 51-68.

Shih, Victor, David Meyer, and Jonghyuk Lee, CCP Elite Database, 2016

Jia, Ruixue, Masayuki Kudamatsu, and David Seim. "Political selection in China: The complementary roles of connections and performance." Journal of the European Economic Association 13.4 (2015): 631-668.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, .Y.H. Performance, Factions, and Promotion in China: The Role of Provincial Transfers. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 27, 41–75 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09764-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09764-1