Abstract

Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) scripts can foster learners’ deep text comprehension. However, this depends on (a) the extent to which the learning activities targeted by a script promote deep text comprehension and (b) whether the guidance level provided by the script is adequate to induce the targeted learning activities effectively; both may be moderated by the learners’ prior knowledge. Inspired by the ICAP framework (Chi and Wylie in Educ Psychol 49:219–243, 2014), we designed a low (LGS) and a high guidance script (HGS) to support learners in performing interactive activities. These activities include generating outputs that go beyond the text, while simultaneously referring to the co-learner. In an experiment, 88 undergraduates were assigned randomly to either the LGS or HGS condition. After reading a text paragraph, LGS participants thought about discussion points for the upcoming collaborative discussion, while HGS participants were (a) prompted to generate outputs individually that go beyond the text and (b) exchange them with their co-learner to provide information about the co-learner’s comprehension state (awareness induction). Subsequently, dyads in both conditions discussed the paragraph in a chat to improve their text comprehension. Prior knowledge moderated the effect of the script guidance level on deep text comprehension: low prior knowledge learners benefitted from the HGS, whereas high prior knowledge learners profited from the LGS. Moderated mediation analyses revealed that these effects can be traced back to patterns of learning activities which differed regarding learners’ prior knowledge. Based on these results, possible directions for future research on CSCL scripting and ICAP are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Afifi, A. A., Kotlerman, J. B., Ettner, S. L., & Cowan, M. (2007). Methods for improving regression analysis for skewed continuous or counted responses. Annual Review of Public Health, 28, 95–111. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.082206.094100.

Berkowitz, M. W., Althof, W., Turner, V. D., & Bloch, D. (2008). Discourse, development, and education. In F. K. Oser & W. Veugelers (Eds.), Getting involved: Global citizenship development and sources of moral values (pp. 189–201). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1080/03057240903101705.

Berkowitz, M. W., & Gibbs, J. C. (1983). Measuring the developmental features of moral discussion. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29(4), 399–410.

Best, R. M., Rowe, M., Ozuru, Y., & McNamara, D. S. (2005). Deep-level comprehension of science texts: The role of the reader and the text. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(1), 65–83. doi:10.1097/00011363-200501000-00007.

Bromme, R., Hesse, F. W., & Spada, H. (2005). Barriers and biases in computer-mediated knowledge communication. And how they may be overcome. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/b105100.

Chan, C. K., Burtis, P. J., Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1992). Constructive activity in learning from text. American Educational Research Journal, 29(1), 97–118. doi:10.2307/1162903.

Chi, M. T. H. (2000). Self-explaining: The dual processes of generating inference and repairing mental models. In R. Glaser (Ed.), Advances in instructional psychology (pp. 161–238). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Chi, M. T. H. (2009). Active-constructive-interactive: A conceptual framework for differentiating learning activities. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(1), 73–105. doi:10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01005.x.

Chi, M. T. H., de Leeuw, N., Chiu, M. H., & LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cognitive Science, 18(3), 439–477.

Chi, M. T. H., & Menekse, M. (2015). Dialogue patterns in peer collaboration that promote learning. In L. B. Resnick, C. Asterhan, & S. Clarke (Eds.), Socializing intelligence through academic talk and dialogue (pp. 263–274). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Chi, M. T. H., Siler, S. A., Jeong, H., Yamauchi, T., & Hausmann, R. G. (2001). Learning from human tutoring. Cognitive Science, 25(4), 471–533. doi:10.1016/S0364-0213(01)00044-1.

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243. doi:10.1080/00461520.2014.965823.

Chiu, J. L., & Chi, M. T. H. (2014). Supporting self-explanation in the classroom. In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.), Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum (pp. 91–103). Washington, DC: Society for the Teaching of Psychology.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research, 64(1), 1–35. doi:10.2307/1170744.

Coté, N., Goldman, S. R., & Saul, E. U. (1998). Students making sense of informational text: Relations between processing and representation. Discourse Processes, 25(1), 1–53. doi:10.1080/01638539809545019.

Cronbach, L. J., & Snow, R. E. (1977). Aptitudes and instructional methods: A handbook for research on interactions. Oxford: Irvington.

De Backer, L., Van Keer, H., & Valcke, M. (2014). Socially shared metacognitive regulation during reciprocal peer tutoring: Identifying its relationship with students’ content processing and transactive discussions. Instructional Science, 43(3), 323–344. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9335-4.

Deiglmayr, A., Rummel, N., & Loibl, K. (2015). The mediating role of interactive learning activities in CSCL: An INPUT-PROCESS-OUTCOME model. The 11th Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL), Gothenburg, Sweden.

Deiglmayr, A., & Schalk, L. (2015). Weak versus strong knowledge interdependence: A comparison of two rationales for distributing information among learners in collaborative learning settings. Learning and Instruction, 40, 69–78. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.08.003.

Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 497–509. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.497.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. doi:10.1177/1529100612453266.

Engelmann, T., Dehler, J., Bodemer, D., & Buder, J. (2009). Knowledge awareness in CSCL: A psychological perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 949–960. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.04.004.

Ertl, B., Kopp, B., & Mandl, H. (2004). Effects of individual prior knowledge on collaborative knowledge construction and individual learning outcome in videoconferencing. (Research Report No. 171). Munich: Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Department of Psychology, Institute for Educational Psychology.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717–741.

Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Stegmann, K., & Wecker, C. (2013a). Toward a script theory of guidance in computer-supported collaborative learning. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 56–66. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.748005.

Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Stegmann, K., Wecker, C., Zottmann, J., & Weinberger, A. (2013b). Collaboration scripts in computer-supported collaborative learning. In C. E. Hmelo-Silver, C. A. Chinn, C. K. K. Chan, & A. O´Donnell (Eds.), The international handbook of collaborative learning (pp. 403–419). New York: Routledge.

Fonseca, B. A., & Chi, M. T. H. (2011). Instruction based on self-explanation. In R. E. Mayer & P. A. Alexander (Eds.), The handbook of research on learning and instruction (pp. 296–321). New York: Routledge.

Gadgil, S., & Nokes-Malach, T. (2012). Overcoming collaborative inhibition through error correction: A classroom experiment. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(3), 410–420. doi:10.1002/acp.1843.

Gijlers, H., & de Jong, T. (2009). Sharing and confronting propositions in collaborative inquiry learning. Cognition and Instruction, 27(3), 239–268. doi:10.1080/07370000903014352.

Häkkinen, P., & Mäkitalo-Siegl, K. (2007). Educational perspectives on scripting CSCL. In F. Fischer, I. Kollar, H. Mandl, & J. Haake (Eds.), Scripting computer-supported collaborative learning—Cognitive, computational and educational approaches (pp. 263–271). US: Springer.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hmelo, C. E., Nagarajan, A., & Day, R. S. (2000). Effects of high and low prior knowledge on construction of a joint problem space. Journal of Experimental Education, 69(1), 36–56. doi:10.1080/00220970009600648.

Janssen, J., & Bodemer, D. (2013). Coordinated computer-supported collaborative learning: Awareness and awareness tools. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 40–55. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.749153.

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., & Kanselaar, G. (2007). Visualization of agreement and discussion processes during computer-supported collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1105–1125. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2006.10.005.

Janssen, J., Kirschner, F., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., & Paas, F. (2010). Making the black box of collaborative learning transparent: Combining process-oriented and cognitive load approaches. Educational Psychology Review, 22(2), 139–154. doi:10.1007/s10648-010-9131-x.

Jeong, H., & Chi, M. T. H. (2007). Knowledge convergence and collaborative learning. Instructional Science, 35(4), 287–315. doi:10.1007/s11251-006-9008-z.

Jeong, H., & Hmelo-Silver, C. (2016). Seven affordances of computer-supported collaborative learning: How to support collaborative learning? How can technologies help? Educational Psychologist, 51(2), 247–265. doi:10.1080/00461520.2016.1158654.

Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23–31. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3801_4.

King, A. (1999). Discourse patterns for mediating peer learning. In A. M. O’Donnell & A. King (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on peer learning (pp. 87–115). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kintsch, W. (2004). The construction-integration model of text comprehension and its implications for instruction. In R. Ruddell & N. Unrau (Eds.), Theroretiocal models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp. 1270–1328). Newark: International Reading Association.

Kirschner, P. A., & Erkens, G. (2013). Toward a framework for CSCL research. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 1–8. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.750227.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1.

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., & Hesse, F. (2006). Collaboration scripts—A conceptual analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 18(2), 159–185. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9007-2.

Lam, R. J. (2013). Maximizing the benefits of collaborative learning in the college classroom. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Sciences Society, Berlin.

McNamara, D. S. (2004). SERT: Self-explanation reading training. Discourse Processes, 38(1), 1–30. doi:10.1207/s15326950dp3801_1.

McNamara, D. S., & Magliano, J. P. (2009a). Self-explanation and metacognition: The dynamics of reading. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 60–81). New York, NY: Routledge.

McNamara, D. S., & Magliano, J. P. (2009b). Toward a comprehensive model of comprehension. In B. H. Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (pp. 297–384). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0079-7421(09)51009-2.

Neal, D. J., & Simons, J. S. (2007). Inference in regression models of heavily skewed alcohol use data: A comparison of ordinary least squares, generalized linear models, and bootstrap resampling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(4), 441–452. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.441.

Nokes, T. J., Hausmann, R. G. M., VanLehn, K., & Gershman, S. (2011). Testing the instructional fit hypothesis: The case of self-explanation prompts. Instructional Science, 39(5), 645–666. doi:10.1007/s11251-010-9151-4.

Nokes-Malach, T., Meade, M. L., & Morrow, D. G. (2012). The effect of expertise on collaborative problem solving. Thinking & Reasoning, 18(1), 32–58. doi:10.1080/13546783.2011.642206.

Nokes-Malach, T., Richey, J. E., & Gadgil, S. (2015). When is it better to learn together? Insights from research on collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 27(4), 645–656. doi:10.1007/s10648-015-9312-8.

Noroozi, O., Teasley, S. D., Biemans, H. J. A., Weinberger, A., & Mulder, M. (2013). Facilitating learning in multidisciplinary groups with transactive CSCL scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 8(2), 189–223. doi:10.1007/s11412-012-9162-z.

O’Donnell, A. M. (1999). Structuring dyadic interaction through scripted cooperation. In A. M. O’Donnell & A. King (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on peer learning (pp. 179–196). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Pfister, H. R. (2005). How to support synchronous net-based learning discourses: Principles and perspectives. In R. Bromme, F. W. Hesse, & H. Spada (Eds.), Barriers and biases in computer-mediated knowledge communication: And how they may be overcome (pp. 39–57). New York: Springer.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Proske, A., Körndle, H., & Narciss, S. (2012). Interactive learning tasks. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 1606–1610). New York: Springer.

Renkl, A. (1999). Learning mathematics from worked-out examples: Analyzing and fostering self-explanations. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14(4), 477–488. doi:10.1007/BF03172974.

Rietzschel, E. F., Nijstad, B. A., & Stroebe, W. (2006). Productivity is not enough: A comparison of interactive and nominal brainstorming groups on idea generation and selection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(2), 244–251. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.04.005.

Roscoe, R. D. (2014). Self-monitoring and knowledge-building in learning by teaching. Instructional Science, 42(3), 327–351. doi:10.1007/s11251-013-9283-4.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2007). Understanding tutor learning: Knowledge-building and knowledge-telling in peer tutors’ explanations and questions. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 534–574. doi:10.3102/0034654307309920.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2008). Tutor learning: The role of explaining and responding to questions. Instructional Science, 36(4), 321–350. doi:10.1007/s11251-007-9034-5.

Rummel, N., & Spada, H. (2005). Learning to collaborate: An instructional approach to promoting collaborative problem solving in computer-mediated settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2), 201–241. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls1402_2.

Stegmann, K., Mu, J., Gehlen-Baum, V., & Fischer, F. (2011). The myth of over-scripting: Can novices be supported too much? In H. Spada, G. Stahl, N. Miyake, & N. Law (Eds.), Connecting computer-supported collaborative learning to policy and practice: CSCL2011 conference proceedings volume I—Long papers (pp. 406–413). Hong Kong: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Teasley, S. (1997). Talking about reasoning: How important is the peer in peer collaboration? In L. B. Resnick, R. Säljö, C. Pontecorvo, & B. Burge (Eds.), Discourse, tools and reasoning: Essays on situated cognition (pp. 361–384). Berlin: Springer.

Trauzettel-Klosinski, S., & Dietz, K. (2012). Standardized assessment of reading performance: The new international reading speed texts IReST. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 53(9), 5452–5461. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8284.

VanLehn, K., Graesser, A. C., Jackson, G. T., Jordan, P., Olney, A., & Rosé, C. P. (2007). When are tutorial dialogues more effective than reading? Cognitive Science, 31(1), 1–60. doi:10.1080/03640210709336984.

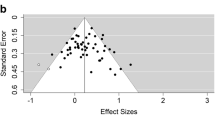

Vogel, F., Wecker, C., Kollar, I., & Fischer, F. (2016). Socio-cognitive scaffolding with computer-supported collaboration scripts: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9361-7.

Webb, N. M. (1989). Peer interaction and learning in small groups. International Journal of Educational Research, 13(1), 21–39.

Weinberger, A. (2011). Principles of transactive computer-supported collaboration scripts. Journal of Digital Literacy, 6(3), 189–202.

Weinberger, A., Kollar, I., Dimitriadis, Y., Mäkitalo-Siegl, K., & Fischer, F. (2009). Computer-supported collaboration scripts. Perspectives from educational psychology and computer science. In N. Balachef, S. R. Ludvigsen, T. de Jong, S. Barnes, & A. W. Lazonder (Eds.), Technology-enhanced learning. principles and products (pp. 155–173). Berlin: Springer.

Wittrock, M. C. (1989). Generative processes of comprehension. Educational Psychologist, 24(4), 345–376. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2404_2.

Wittwer, J., & Renkl, A. (2008). Why instructional explanations often do not work: A framework for understanding the effectiveness of instructional explanations. Educational Psychologist, 43(1), 49–64. doi:10.1080/00461520701756420.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Cindy Hmelo-Silver and three anonymous reviewers for their very valuable critiques and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Self-explanation prompt adapted from Chi et al. (1994, p. 477)

Please explain in this text box what the text paragraph means to you, that is

-

What new information does it provide to you?

-

How does it relate to what you have already read?

-

Does it give you a new insight into your understanding how the circulatory system works?

-

Does it raise questions in your mind?

Tell us whatever is going through your mind, even if it seems unimportant!

Appendix 2

Examples of posttest questions for the assessment of deep text comprehension adapted from Chi et al. (2001, p. 523, 525).

What results at the cellular level from having a hole in the septum?

-

(a)

This can result in the carbon dioxide concentration being increased in the body cells X

-

(b)

This can result in the body cells no longer receiving any oxygen

-

(c)

This can result in the blood of the pulmonary veins being less oxygenated

-

(d)

This can result in the lungs having to take up more carbon dioxide

Where is the failure located, in most instances if the heart stops functioning properly?

-

(a)

Left atrium

-

(b)

Left ventricle X

-

(c)

Right atrium

-

(d)

Right ventricle

To identify, for instance, the correct answer to the question of where the failure is located in the most cases when the heart stops working properly, one has to make the following line of reasoning: based on the text information that the atria pumps blood to the ventricles, the right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs and the left ventricle pumps blood to the whole body, one has to insert the information that pumping blood in the whole body (a great area with long distances) is a task requiring more physical effort than the tasks of transporting blood in the ventricles or lungs from prior knowledge. Based on the knowledge that more effort causes a greater physical strain, this allows the conclusion that, in the majority of cases, the left ventricle is the cause of heart problems (cf. Chi et al. 2001).

Appendix 3

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mende, S., Proske, A., Körndle, H. et al. Who benefits from a low versus high guidance CSCL script and why?. Instr Sci 45, 439–468 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-017-9411-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-017-9411-7