Abstract

Introduction

Various risk stratification methods exist for patients with pulmonary embolism (PE). We used the simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) as a risk-stratification method to understand the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) PE population.

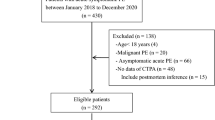

Materials and methods

Adult patients with ≥ 1 inpatient PE diagnosis (index date = discharge date) from October 2011–June 2015 as well as continuous enrollment for ≥ 12 months pre- and 3 months post-index date were included. We defined a sPESI score of 0 as low-risk (LRPE) and all others as high-risk (HRPE). Hospital-acquired complications (HACs) during the index hospitalization, 90-day follow-up PE-related outcomes, and health care utilization and costs were compared between HRPE and LRPE patients.

Results

Of 6746 PE patients, 95.4% were men, 67.7% were white, and 22.0% were African American; LRPE occurred in 28.4% and HRPE in 71.6%. Relative to HRPE patients, LRPE patients had lower Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (1.0 vs. 3.4, p < 0.0001) and other baseline comorbidities, fewer HACs (11.4% vs. 20.0%, p < 0.0001), less bacterial pneumonia (10.6% vs. 22.3%, p < 0.0001), and shorter average inpatient lengths of stay (8.8 vs. 11.2 days, p < 0.0001) during the index hospitalization. During follow-up, LRPE patients had fewer PE-related outcomes of recurrent venous thromboembolism (4.4% vs. 6.0%, p = 0.0077), major bleeding (1.2% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.0382), and death (3.7% vs. 16.2%, p < 0.0001). LRPE patients had fewer inpatient but higher outpatient visits per patient, and lower total health care costs ($12,021 vs. $16,911, p < 0.0001) than HRPE patients.

Conclusions

Using the sPESI score identifies a PE cohort with a lower clinical and economic burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- DVT:

-

Deep vein thrombosis

- ECHO:

-

Echocardiogram

- ESC:

-

European Society of Cardiology

- HAC:

-

Hospital-acquired complication

- HRPE:

-

High-risk pulmonary embolism

- HRU:

-

Health care resource utilization

- ICD-9-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

- IMPACT:

-

In-hospital mortality for pulmonary embolism using claims data

- LMWH:

-

Low-molecular-weight heparin

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- LRPE:

-

Low-risk pulmonary embolism

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- NOAC:

-

Novel oral anticoagulant

- PE:

-

Pulmonary embolism

- SAS:

-

Statistical analysis software

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- sPESI:

-

Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index

- STD:

-

Standardized difference

- UFH:

-

Unfractionated heparin

- VHA:

-

Veterans Health Administration

- VQ:

-

Lung ventilation/perfusion

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

References

Weeda ER, Wells PS, Peacock WF et al (2017) Hospital length-of-stay and costs among pulmonary embolism patients treated with rivaroxaban versus parenteral bridging to warfarin. Intern Emerg Med 12(3):311–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1552-1

Rali P, Gandhi V, Malik K (2016) Pulmonary embolism. Crit Care Nurs Q 39(2):131–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000106

Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S (2011) Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 171(9):831–837. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178

Heit JA, Spencer FA, White RH (2016) The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thormbolysis 41(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-015-1311-6

Bĕlohlávek J, Dytrych V, Linhart A (2013) Pulmonary embolism, part I: epidemiology, risk factors and risk stratification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism. Exp Clin Cardiol 18(2):129–138

Dasta JF, Pilon D, Mody SH et al (2015) Daily hospitalization costs in patients with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism treated with anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Res 135(2):303–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.024

LaMori JC, Shoheiber O, Mody SH, Bookhart BK (2015) Inpatient resource use and cost burden of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the United States. Clin Ther 37(1):62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.10.024

Jiménez D, Lobo JL, Barrios D, Prandoni P, Yusen RD (2016) Risk stratification of patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Intern Emerg Med 11(1):11–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1388-0

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J et al (2016) Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 149(2):315–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

Stamm JA, Long JL, Kirchner HL, Keshava K, Wood KE (2014) Risk stratification in acute pulmonary embolism: frequency and impact on treatment decisions and outcomes. South Med J 107(2):72–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000053

Aujesky D, Mazzolai L, Hugli O, Perrier A (2009) Outpatient treatment of pulmonary embolism. Swiss Med Wkly 139(47–48):685–690. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2009.12661

Hellenkamp K, Kaeberich A, Schwung J, Konstantinides S, Lankeit M (2015) Risk stratification of normotensive pulmonary embolism based on the sPESI—does it work for all patients? Int J Cardiol 197:162–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.065

Konstantinides S, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) et al (2014) 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 35(43):3033–3069. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283

Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp. Accessed 6 July 2016

Fermann GJ, Erkens PM, Prins MH, Wells PS, Pap ÁF, Lensing AW (2015) Treatment of pulmonary embolism with rivaroxaban: outcomes by simplified pulmonary embolism severity index score from a post hoc analysis of the EINSTEIN PE study. Acad Emerg Med 22(3):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12615

Masotti L, Panigada G, Landini G et al (2016) Simplified PESI score and sex difference in prognosis of acute pulmonary embolism: a brief report from a real life study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 41(4):606–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-015-1260-0

Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA (2011) An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20(6):560–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.2109

Ozsu S, Ozlu T, Şentürk A et al (2014) Combination and comparison of two models in prognosis of pulmonary embolism: results from Turkey pulmonary embolism group (TUPEG) study. Thromb Res 133(6):1006–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.02.032

Dentali F, Riva N, Turato S et al (2013) Pulmonary embolism severity index accurately predicts long-term mortality rate in patients hospitalized for acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 11(12):2103–2110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12420

Jiménez D, Aujesky D, Moores L et al (2010) Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 170(15):1383–1389. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.199

Barco S, Mahmoudpour SH, Planquette B, Sanchez O, Konstantinides SV, Meyer G (2018) Prognostic value of right ventricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers in patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy873.

Shafiq A, Lodhi H, Ahmed Z, Bajwa A (2015) Is the pulmonary embolism severity index being routinely used in clinical practice? Thrombosis. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/175357. 2015.

Sorbello D, Dewey HM, Churilov L et al (2009) Very early mobilisation and complications in the first 3 months after stroke: further results from phase II of a very early rehabilitation trial (AVERT). Cerebrovasc Dis 28(4):378–383. https://doi.org/10.1159/000230712

Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Svendsen ML, Johnsen SP (2011) In-hospital medical complications, length of stay, and mortality among stroke unit patients. Stroke 42(11):3214–3218. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610881

Masotti L, Panigada G, Landini G et al (2015) Comparison and combination of a hemodynamics/biomarkers-based model with simplified PESI score for prognostic stratification of acute pulmonary embolism: findings from a real world study. Int J Res Med Sci 3(11):3230–3237. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20151168

Elias A, Mallett S, Daoud-Elias M, Poggi JN, Clarke M (2016) Prognostic models in acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6(4):e010324. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010324

Piran S, Le Gal G, Wells PS et al (2013) Outpatient treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 132(5):515–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2013.08.012

Berghaus TM, Thilo C, Bluethgen A, von Scheidt W, Schwaiblmair M (2010) Effectiveness of thrombolysis in patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism: influence on length of hospital stay. Adv Ther 27(9):648–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-010-0058-x

Coleman CI, Kohn CG, Crivera C, Schein JR, Peacock WF (2015) Validation of the multivariable in-hospital mortality for pulmonary embolism using claims data (IMPACT) prediction rule within an all-payer inpatient administrative claims database. BMJ Open 5(10):e009251. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009251

Funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

WFP has received grants from Abbott, Alere, Banyan, Cardiorentis, Janssen, Portola, Pfizer, Roche, and ZS Pharma; is a consultant to Alere, Beckman, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cardiorentis, Instrument Labs, Janssen, Phillips, Portola, Prevencio, Singulex, The Medicine’s Company, and ZS Pharma; and also has ownership interests at the Comprehensive Research Associate LLC, Emergencies in Medicine LLC. CIC has received grant funding and consulting fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Raritan, NJ and Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. PW receives speaker fees from Bayer Healthcare and Daiichi Sankyo, writing committee fees from Itreas, and grant support fees from Pfizer/BMS. GJF has received research support from Novartis, Siemens, Pfizer, Portola, and PCORI; has advised Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; and receives speaker fees from Janssen. CC and JS and are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs. LW and OB are employees of STATinMED Research, which is a paid consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wells, P., Peacock, W.F., Fermann, G.J. et al. The value of sPESI for risk stratification in patients with pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis 48, 149–157 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-019-01814-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-019-01814-z